1. Introduction

In modern times, businesses, especially the service sector, have begun to encounter increased pressure from various stakeholders to think about how their actions affect the natural environment and society [

1]. Ecologists constantly struggle to raise public awareness of the decline in natural reserves [

2]. The variation in the natural environment and the substantial intensification of air, land, and water pollution lead organizations to shift their dependence away from fossil fuels, which produce ecological concerns, and to take advantage of renewable resources [

3,

4,

5]. Moreover, to enhance public awareness, provincial and international laws to save the natural environment also oblige firms to be concerned about how their activities affect the natural environment and to adopt green or environmentally friendly production processes [

6,

7]. According to Masocha [

8], this situation has also altered stakeholders’ preferences and needs, and urged them to choose the firm’s products or services that cause the least harm to the natural environment. However, firms need to assure consumers that the standards of their services and goods will be high, and that their actions will not negatively affect the environment.

Firms can use green approaches to address concerns about the natural environment. Such activities are characterized by environmentally friendly practices that an organization can adopt in order to become a more sustainable organization. These businesses focus on reducing their impact on the environment through initiatives that reduce their unethical environmental practices by ensuring that corporate practices meet a minimum level of sustainability. Corporate green practices fluctuate from sector to sector, and are often unique to the type of firm and the product or service it provides [

9]. The corporate green performance (CGP) concept centres on upgrading current practices or launching new products and practices [

10] in such a way that it both fulfils the quality needs of stakeholders and results in improved environmental performance [

11]. CGP is related to green management, green infrastructure, and procedures to lessen the environmental problems triggered by the organization’s activities [

4,

12]. Another factor connected to CGP is green innovation, whereby an organization presents unique ideas that empower management to think and work for society and mitigate other environmental hazards. Nevertheless, according to Wang [

13] and Zhang and Rong [

14], CGP research is in the initial stage, and there is a strong need for literature to be enriched in this field.

Total quality management is a relevant factor that could help firms meet their green performance objectives [

15]. TQM is a control structure which can increase both individual and firm performance. This system enables companies to gain a competitive advantage and helps them maintain their advantage through improvements in standards and quality, at the lowest possible delivery time and at favourable cost [

16,

17]. Total quality management is an environment-oriented method which can help diminish waste through the effective and efficient consumption of resources and reserves [

8]. Likewise, it involves the delivery of continuous progress, training, and development, and it enriches individual competencies to transform or better the performance of existing services or products [

17,

18,

19].TQM therefore plays a vital role in boosting the ability of companies to attain green performance goals.

Furthermore, the idea of organizational culture has become popular in studies on social responsibility over the last decade. It offers an access point for corporate social performance in the fields of human resources and organizational behaviour. This system of words, shapes, categories, and images helps researchers interpret an individual’s situation [

19]. Studies have shown that an organization’s culture requires mutual values that must be followed as officially authorized conduct [

20,

21]. Conventionally, qualitative approaches for analyzing organizational culture have been used [

22]; however, it is impossible to create systematic comparisons through these research methods [

23]. Hence, quantitative methods offer more practical understandings for cross-sectional organizational analysis and behavioural change projects, such as survey methods [

24]. In previous research, organizational culture has also been analyzed with mixed qualitative and quantitative methods, e.g., Siehl and Martin [

24].

Furthermore, trust in corporate culture can fundamentally change the way companies work, in addition to generating economic value for shareholders [

25,

26]. A company’s working environment is composed of workers (including top management) and technological tools and skills under their usage. They have numerous conflicts that can dilute the more significant insights on how these constituencies think and view each other [

27]. In the successful and smooth execution of a transition program, understanding the organizational culture plays a critical role [

28,

29]. TQM and CGP are a part of organizational culture and values in an organizational environment [

30]. The creation of social responsibility is a shift in the orientation of values, with an emphasis on influencing attitudes and shaping personal roles to meet individual and public interests. Organizational culture is usually considered the primary reason why organizational change programs fail, for example, corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the adoption of environmental practices. Some scholars suggest that if the organization’s fundamental culture remains the same, a change in methods, tactics, or strategies may result in failure [

31]. Employee norms, beliefs, and values are likely to play a significant role in perceptions about TQM and the actions of employees [

32]. Consequently, in companies with a sophisticated socially responsible culture, leaders and members are concerned for their own interests and benefits and acknowledge other stakeholders‘ needs [

33]. Several studies suggest that organizational culture affects TQM and CGP’s operating processes and effectiveness [

30,

34,

35].

Expanding the concept of social responsibility from the developed world to the developing world is a challenge and an opportunity that ought to be taken on explicitly. Social responsibility and social responsiveness in healthcare would include both a new social aspect of care and new organizational practices within the health sector and other healthcare organizations [

36]. However, malfeasance may ruin an organization, particularly a hospital or other healthcare organization [

37]. This sector involves a varied group of stakeholders, such as patients, regulators, political authorities, health specialists, the media, the general public, and NGOs. All of these stakeholders expect that companies should understand their social and environmental obligations so that they might alleviate the adverse effects of their operations and contribute to the betterment of the community. Further, this sector has not yet fully received the attention of researchers in developing countries. This is especially true for Pakistan, where the health sector has never been examined in terms of either the implementation of TQM practices or green performance. Moreover, trust in corporate culture can fundamentally change the way companies work, in addition to generating economic value for shareholders [

25,

26]. In the successful and smooth implementation of any transition program, understanding the organizational culture plays a critical role [

28,

29]. Further, in organizational environment, TQM and CGP are considered a part of organizational culture [

30]. Moreover, organizational culture has rarely been examined as a mediator between TQM practices and CGP in the health sector and the relevant target population.

Companies that implement green performance and quality management initiatives have the potential to address issues related to evolving consumer expectations about the environment and quality concerns [

38,

39]. Moreover, Fernando et al. [

6] and Wang [

40] believe that the concept of green performance is at the introductory stage, and that the literature in this area strongly needs to be enriched. Additionally, the research related to this issue has produced mixed results. For example, Li et al. [

4] examined TQM’s effect on Chinese manufacturing companies’ green innovation performance and noticed a negative link between these factors. Similarly, Abbas and Sağsan [

1] reported the same negative impact while measuring the effect of environmental management and quality management on firms’ performance. Meanwhile, Tasleem et al. [

41] found a positive and significant relationship between corporate sustainable development and total quality management practices. Moreover, Shahzad et al. [

42] showed positive and significant outcomes in CSR due to the impact of knowledge absorptive capacity on CGP. Nevertheless, Zhang et al. [

43] declared that CGP objectives were achieved only through technical and financial support from the government, because attempting to meet these objectives increased expenses and the time of production.

These mixed findings relating to TQM, CGP, and OC indicate the need for further study into the relationship between these variables. Besides, less attention has been paid to developing countries and their health sectors. This is the case for Pakistan, where the concepts of green performance and environmental sustainability are in the introductory phase, and where the relationship between TQM and CGP in the health sector has rarely been examined [

4]. Thus, it is worth conducting a research study focusing on the health sector as a separate part of the service sector. Further, to gain a better understanding of TQM implementation in the hospital sector, the present study focuses on small and medium-sized private hospitals operating all over Pakistan. In particular, the purpose of this study is to enrich the existing literature by identifying and confirming the enablers and outcomes of TQM specifically within the hospital sector in the context of Pakistan. Moreover, the relationship between the implementation of TQM practices and green performance is also examined, given that past results relating to this issue have been contradictory. The current study also validates the argument that enhancements in the CGP of private hospitals can be achieved in an efficient manner through the implementation of TQM in developing countries. In addition, this research supports the argument that OC mediation affects the relationship between TQM and CGP in the health sector. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this mediation effect has not been previously investigated in previous TQM and green performance studies performed in Pakistan, thus adding another key contribution to the body of knowledge in TQM practices and green performance.

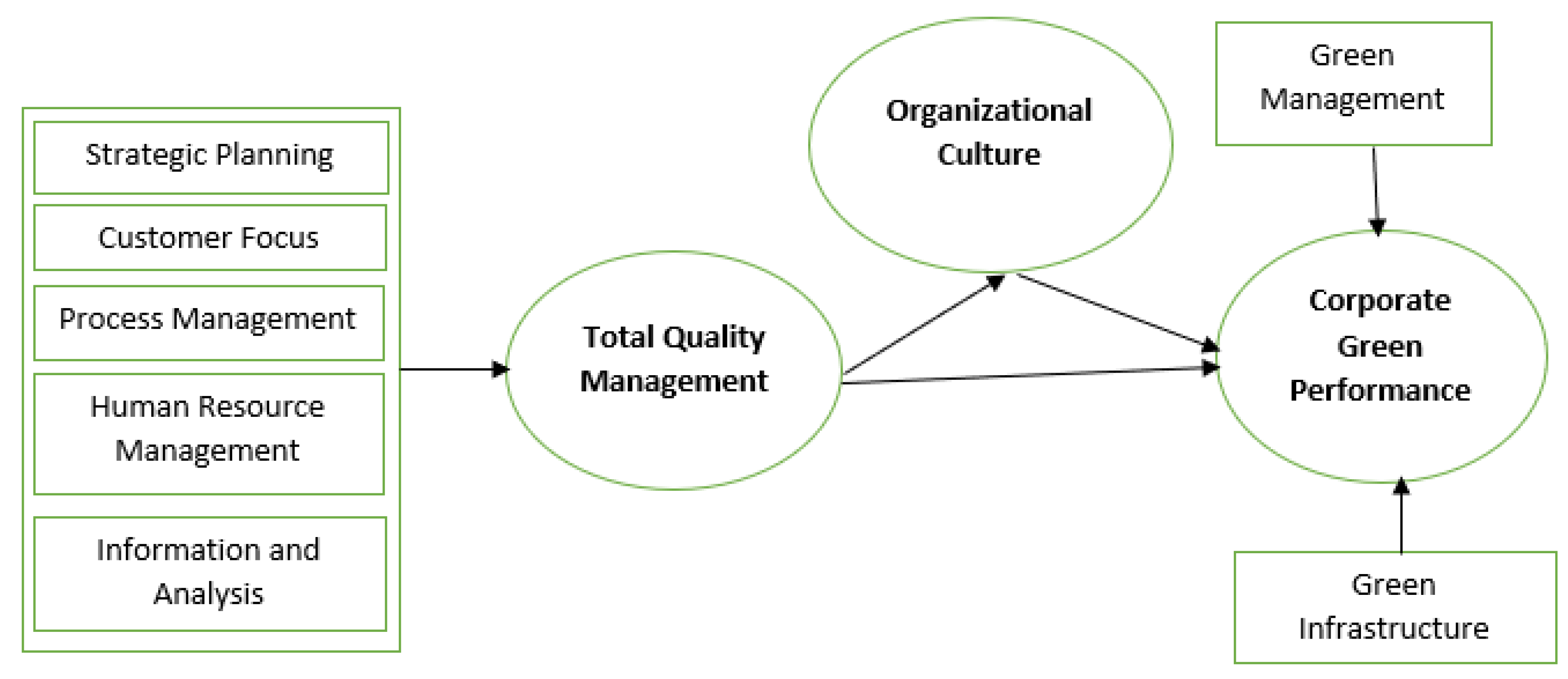

Considering the significance of TQM in the modern world of business, this study shows how companies are able accomplish corporate green performance goals, how the private health sector is able utilize their essential tools (such as TQM), and how OC mediates this relationship. Following institutional theory and the American ‘Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award’ (MBNQA), the researchers used five TQM practices, including strategic planning, customer focus, process management, human resource management, and information and analysis. Moreover, corporate green performance is quantified for two components, namely green management performance and green infrastructure, following the instructions of Li et al. [

4] and Xie et al. [

12]. Finally, OC is determined as per Adil’s [

44] recommendations. Thus, the following questions are addressed in the present article:

Research Question 1: What is the impact of TQM practices on corporate green performance?

Research Question 2: Does organizational culture mediate the relationship between total quality management practices and corporate green performance?

Structure of the Study

Going forward, this paper is structured as follows: In

Section 2, we briefly elaborate on the theoretical background, namely green theory and institutional theory, and introduce total quality management as a formative construct. In same section, we develop our hypotheses and introduce a comprehensive model. In

Section 3, we discuss the methodology, namely, our sample, the measurement model, and the process of data collection. We present the results in

Section 4, which are followed by a discussion on the implications and limitations (

Section 5), as well as important conclusions (

Section 6).

4. Data Analysis and Results

PLS-SEM is used to analyze data in this study due to its ability to measure complicated models. It is generally more appropriate to use when the study includes numerous variables and complex models together [

137]. Khalil et al. [

138], Khalil et al. [

139] and Hair et al. [

137] propose that PLS-SEM can offer a strong ground for the confirmation of theories and obtain results that help us explain the application of theories.

Structure equation modelling is composed of two sub-models in SmartPLS: (1) the inner model and (2) the outer model. The internal model applies to the relationship between the dependent and independent variables, while the external or outer model defines the relationship between the dependent variables and specified indicators [

137]. Further, for testing common method bias, this study used Lindell and Whitney’s [

140] and Podsakof et al.’s [

141] method. In this study, we employ a theoretically unrelated construct (innovation) to adjust the correlation among the principal constructs. For instance, the “InnVar” is used as the innovation variable. After running the test, the correlation between Innovation and other variables, such as innovation and strategic planning or innovation and culture, is very low. After squaring the correlation, the maximum shared variance with the other variables can be noticed. The maximum shared variance was about 0.1, so we can conclude that we do not have common method bias.

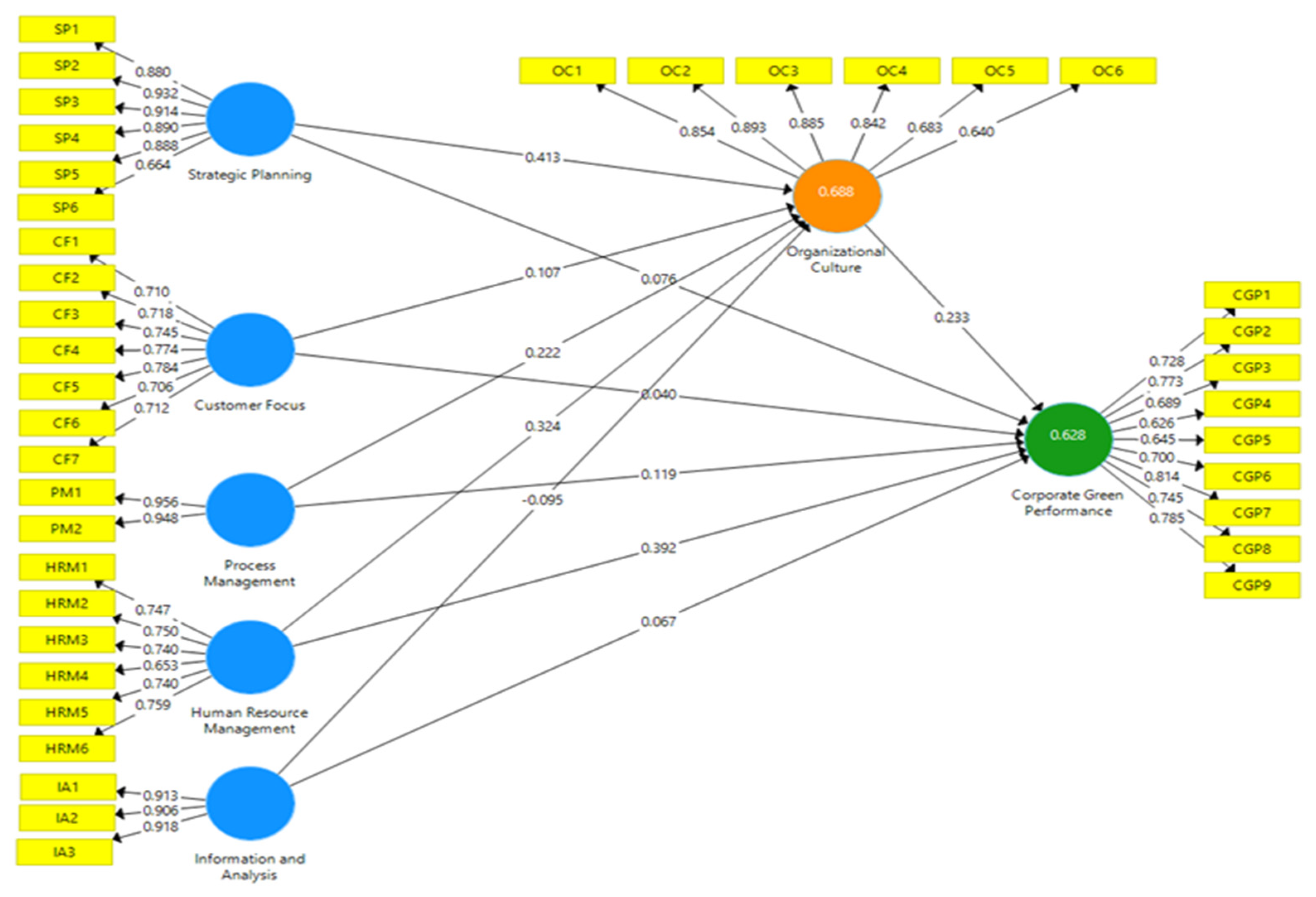

The presentation of results in this study follows the style explained by Henseler et al. [

142]. At first, regarding their style, the reliability and validity of the concerned variables needed to be checked by generating reliable estimates using the PLS algorithm for the outer model, which also refers to a measurement model. Later, a structural model was estimated by using the bootstrapping option for the inner model in SmartPLS. The results in

Figure 3 demonstrate the estimation of the measurement model in which we generally estimate the relationships between the construct (latent variable) and its indicators.

The results of Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and average variance extracted (AVE) for the variables used in this study are shown in

Table 5. Results clearly show that all the Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) values are higher than 0.7, surpassing the minimum acceptable criteria. For each variable, AVE’s values are more than 0.5, which meets the criteria for acceptable convergent validity.

Discriminant validity shows that each variable’s measure is significantly related to its variable and less allied to other variables in the study [

98]. There are two tests for discriminant validity: (1) cross-loading; and (2) the Fornell–Larcker test. Cross-loading is used to measure the indicator level of discriminant validity, while the Fornell–Larcker test is a test to measure the variable level of discriminant validity.

The values for cross-loadings are shown in

Table 6. Results demonstrate that all indicators have the highest relationship with their variables.

The results of the Fornell–Larcker test are illustrated in

Table 7. For a construct to stand valid, it must have more variance with its indicators than with other variables’ measures. Results show that all variables share the highest variance with their variables. Furthermore, the present study meets the required criteria of the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio that was suggested by Hair et al. [

95] (see

Table 8).

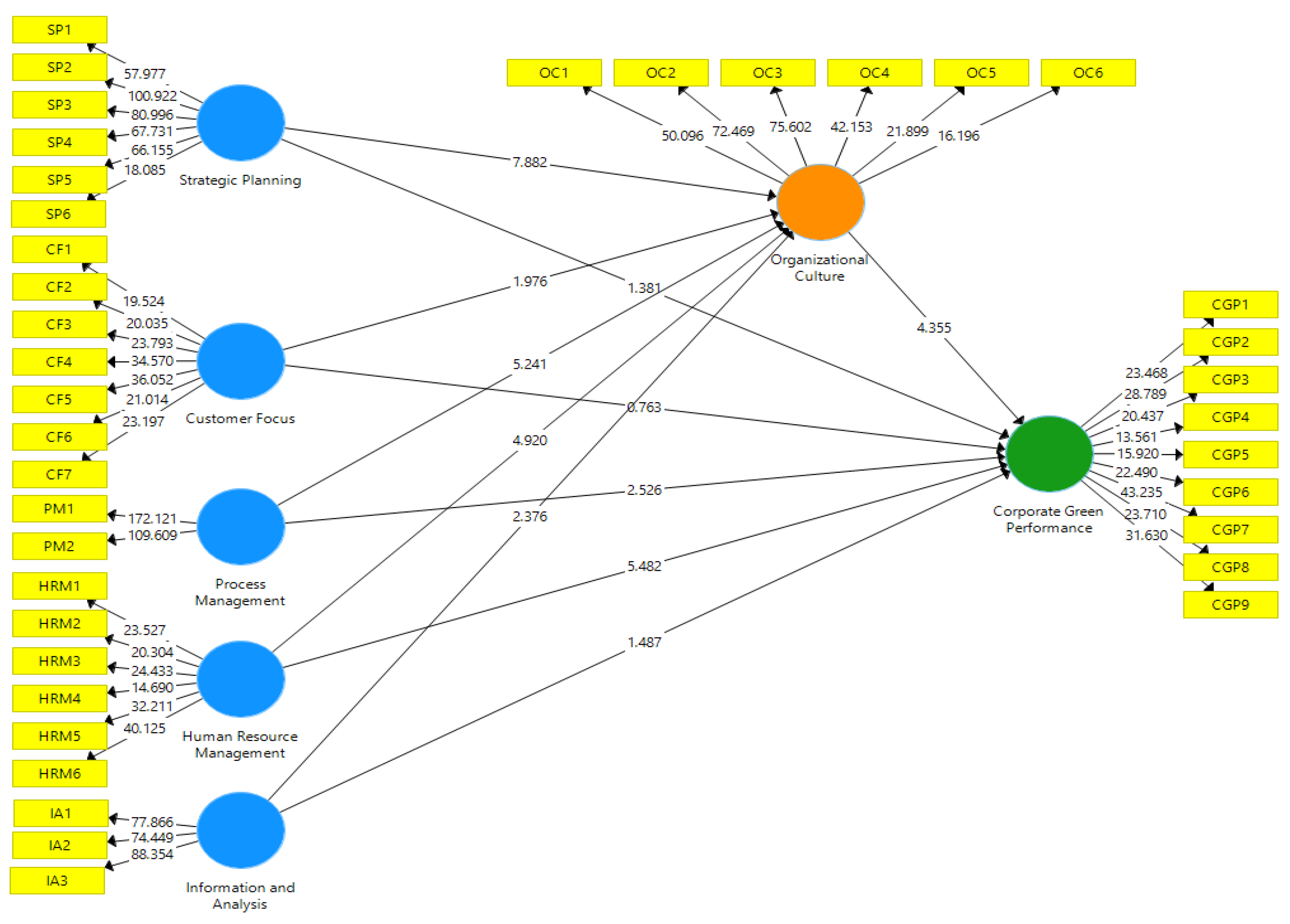

4.1. The Structure Model and Hypotheses Testing

The structural model measures the relationship between the given variables of a study. It is nothing more than the regression analysis.

Figure 4 shows the results of the structure model that includes a beta value which reflects the value of the impact of the explanatory variables on the dependent variable. The sign with the beta value shows the direction of the impact. The structure model also provides

t-value and

p-value. These values are used to measure the significance of the relationship. For a significant relationship,

t-value must be greater ±1.96 or

p-value needs to be less than 0.05. Signs with

t-value also show the direction of the relationship, just like a sign with the beta value. The structure model results also include the value of

R2, which shows the strength of the relationship. These values have importance when we want to predict the future on the basis of the study result following Frost [

143].

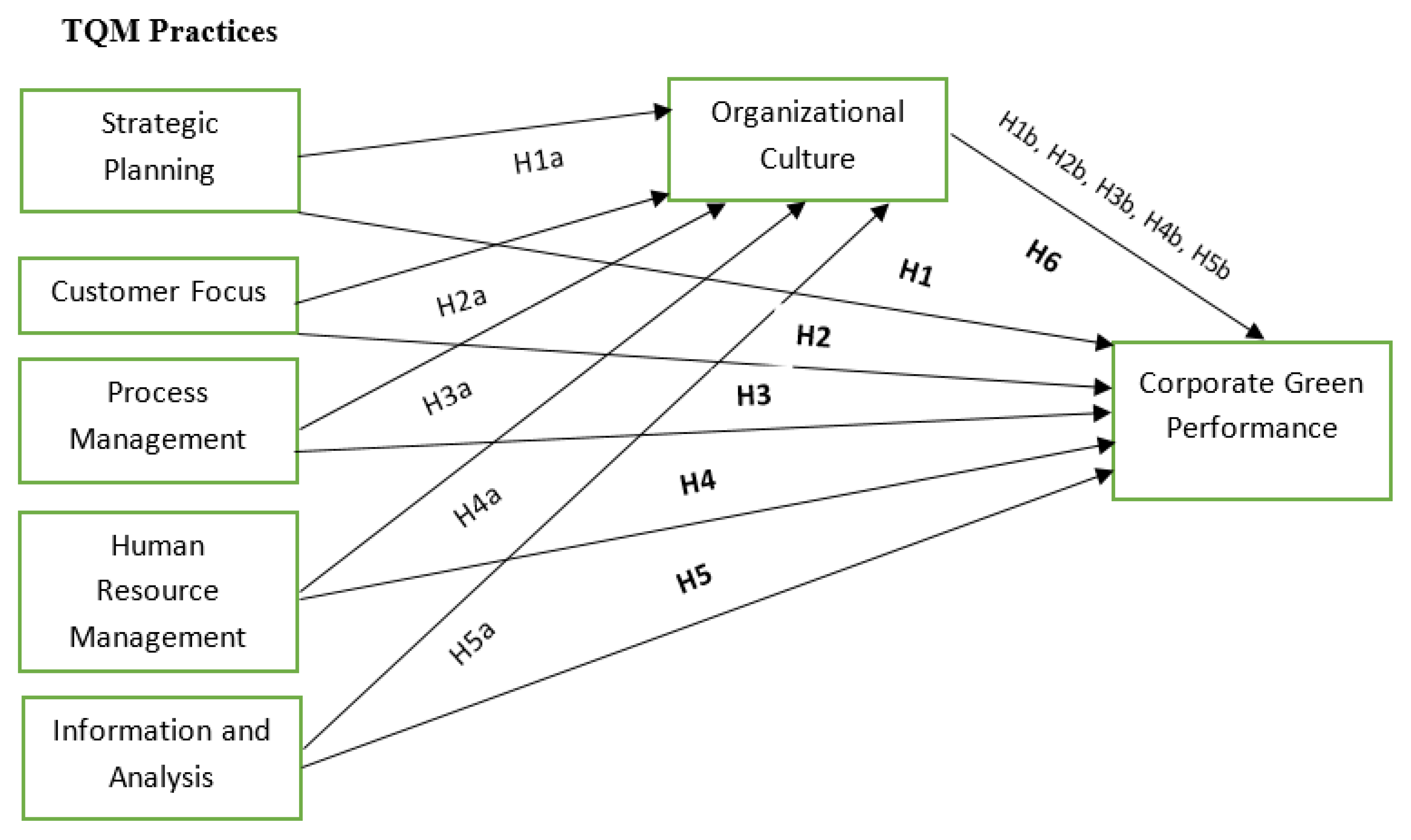

This study was based on six main hypotheses which have direct relationships, and only two hypotheses were not accepted out of the six hypotheses. For instance, SP has a significant effect on CGP (

p = 0.00, β = 0.176,

t-value = 4.381), and the hypothesis H1 is supported. Likewise, SP positively influences OC (

p = 0.00, β = 0.413,

t-value = 7.882) and this validated the second hypothesis (H1a). However, the CF does not affect CGP (

p > 0.05, β = 0.040,

t-value = 0.763) and the third hypothesis H2 is not supported. Though, CF has a positive influence on OC (

p = 0.049, β = 0.107,

t-value = 1.976) and endorsed the hypothesis H2a. PM also positively affects CGP (

p = 0.012, β = 0.119,

t-value = 2.526) and thus we have accepted the third main hypothesis H3. Furthermore, the PM positively influenced OC (

p = 0.00, β = 0.222,

t-value = 5.241) and this supported the hypothesis H3a. HRM has a positive impact on CGP (

p = 0.00, β = 0.392,

t-value = 5.482) and this supported the fourth hypothesis H4. The HRM positively influenced OC (

p = 0.00, β = 0.324,

t-value = 4.920) and this supported the hypothesis H4a. Meanwhile, IA has no impact on CGP (

p > 0.05, β = 0.067,

t-value = 1.487), and so the fifth hypothesis (H5) is not validated. However, IA positively impacts OC (

p = 0.018, β = 0.095,

t-value = 2.376) and so we have accepted the hypothesis H5a. Similarly, OC has a definite impact on CGP (

p = 0.00, β = 0.233,

t-value = 4.355) and this supported the hypothesis H6. The results demonstrate below in

Table 9.

4.2. Mediation Testing

According to the proposed model of this study, the organizational culture was used as a mediating variable. To assess whether this mediation impact strengthens or weakens the relationship between the independent and dependent variables, and to see its influence, we can refer to the results of the indirect effects of the model and compare these results to the direct effects. According to the results shown in

Table 10, organizational culture plays a significant part in positively influencing the relationship. OC plays a positive mediating role between SP, CF, PM, HRM, IA, and CGP. OC positively and significantly mediated the relationship between SP and CGP (

p = 0.00, β = 0.096,

t-value = 4.023,) and this validated the hypothesis H1b. However, OC has no significant mediation impact in the relationship between CF and CGP (

p > 0.05, β = 0.025,

t-value = 1.618) and H2b is therefore not supported. Furthermore, OC significantly and positively mediates the relationship among the PM and CGP (

p = 0.002, β = 0.052,

t-value = 3.174) and this validates H3b. Likewise, OC positively mediates the relationship between HRM and CGP (

p = 0.00, β = 0.075,

t-value = 3.636) and this has supported H4b. Moreover, IA has no influence on CGP except in the presence of OC, and this relationship boosted the impact (

p = 0.021, β = 0.022,

t-value = 2.211) and so confirmed H5b.

4.3. The Predictive Relevance of the Model

In the present research, two factors are verified with

R square and cross-validated redundancy to assess the model’s predictive relevance.

R square values mean that the endogenous variable is explained jointly by all exogenous variables.

Table 11 demonstrates that all independent variables describe 68.8% of OC, whereas 62.8% of CGP is illustrated by all independent variables. An

R square value in the range of 0.02 to 0.13 shows weak or small explanation, the

R square value in the array of 0.13 to 0.26 is moderate, and

R square value greater than 0.26 indicates that the explanation is highly efficient [

100]. As

Table 10 shows, the

R square value for CGP and OC indicates a strong effect. The cross-validated redundancy is measured by running blindfolding in PLS tools. According to some prior researchers, the value of

Q2 must be more than zero [

142,

144,

145,

146,

147].

Table 12 reveals that the

Q2 value of CGP and OC fulfils the abovementioned required criteria.

4.4. Model Fit

The standardized root means squared residuals (SRMR) shows an approximate fit of the model. It captures the magnitude of how the model’s implied correlation matrix is differed with the observed correlation matrix and provides an estimate of the average magnitude of these differences. The lower the value of SRMR, the better a model fit is. A model is considered to have a good fit if the SRMR is less than or equal to 0.08 [

137,

148]. Some researchers follow a softer point of SRMR value of less than 0.10. The value of the SRMR of the model in this study is 0.068. This value confirms that the model is correctly specified and can be considered as acceptable. Therefore, the model meets the criteria of being fit in terms of its SRMR value.

5. Discussion

The present research seeks to examine the impact of total quality management practices on corporate green performance via organizational culture mediation. The data was collected from medium and large private hospitals situated in six major commercial cities in Pakistan, including Karachi, Lahore, Multan, Islamabad, Peshawar, and Faisalabad via personal visits. The data was congregated from management personnel at the lower, middle, and upper levels, providing detailed insights and information about firms’ practices and policies. In addition, they are also the key people in their organizations who exchange data and enforce organizational policies. The researchers used SmartPLS software for data analysis. The findings have revealed a positive and significant impact of TQM on CGP. As per the structure model, results also indicated that three out of five TQM practices, namely strategic planning (H1), process management (H3), and human resource management (H4) have a positive and significant impact on CGP through the acceptable values of

p, β, and

t. Therefore, the hypotheses H1, H3, and H4 stand supported (see

Table 9 and

Figure 4). These findings confirm studies by Abbass [

13] and Green et al. [

38], who found the significant and positive influence of total quality management on corporate green management performance in context of supply chain management. However, two out of five dimensions, namely customer focus (H2) and information and analysis (H5), negatively influence CGP with their non-significant values following the structural equation model. Hence, the hypotheses H2 and H5 are not supported. The negative relationship is not surprising, as it is observed that the health sector’s major focus might be on inside practices and operations of organization, such as strategic planning, process management, and human resource management, which are their main priority while the concept of green performance is at the understanding stage in Pakistan. Therefore, these results are comparable to Li et al. [

4] and Suleman & Gul [

149], who concluded that there was a negative link between corporate green innovation and total quality management practices in Chinese manufacturing firms. Bearing in mind TQM’s ideology of customer focus and continuous improvement, organizations typically follow quality management strategies to enhance the efficiency of existing goods and services to meet customer and stakeholder demands. Since the whole process is almost under control in the TQM system to evade deviations and defects, this structure can discourage businesses from innovation [

4]. Based on the current study outcomes, it can be clearly said that the sampled companies are efficiently capitalizing on TQM, which helps them to increase their green performance.

There are several interrelated factors, such as top management engagement, technological knowledge, infrastructure, and capitalization on the modern technologies, which depend on the successful implementation of TQM practices and the achievement of CGP goals, that could be a main reason for the significant and constructive relationship between TQM practices and CGP. The incorporation of the new technologies with TQM helps companies to turn their conventional processes into green processes [

4,

13]. By following TQM practices, companies can boost their employees’ knowledge and abilities regarding the effective utilization of resources. Employees are more empowered and motivated when working in an environment that ensures that their goods and services serve exceptional quality to society and protect the natural environment. This study suggests that if a firm can manage its TQM activities effectively, it will enhance the skills, abilities, and level of motivation of the employees to use the resources in productive ways, resulting in augmented CGP.

Total quality management practices with positive values have also been shown to have a positive and significant influence on OC. Therefore, strategic planning (H1a), customer focus (H2a), process management (H3a), human resource management (H4a), and information and analysis (H5a) are supported. These findings are related to Eniola et al.’s [

150] work, which found that an organized TQM program and practices enhance firm culture and skills. These results are also consistent with Baird et al. [

151], who demonstrated that there was a positive relationship between OC and TQM practices. This substantial result indicates that if a firm can effectively handle its TQM practices, it will heighten its culture and skills to perform and contribute accordingly. This substantial result demonstrates that the target sampled private hospitals are effectively relying on TQM practices to attain perfection in the development of OC and TQM, drastically encouraging companies’ competencies to perform its starring role in the development of culture. Another interesting finding from the current study is that OC is positively associated with CGP (

p = 0.05, β = 0.233,

t-value = 4.355), so H6 is also accepted. The recognition of this relationship extends Yu and Choi [

30]’s finding that OC significantly influences the CGP.

5.1. Practical and Theoretical Implications

The current research has several implications from a managerial and theoretical viewpoint. From the industrial view, the abovementioned results show that TQM practices are significant to attaining CGP goals in the health sector. These results also explain the vital role of organizational culture in accomplishing CGP goals, and shows that through assimilating TQM and OC practices, an organization can accomplish perfection in day-to-day operations and lead themselves towards strategic and competitive advantage. The structural analysis values reveal that CGP objectives are directly linked to the effective implementation of TQM and OC practices. Organizations which actively play a part in societal development programs and effectively engaged with quality management activities are able to outpace the followers of conventional practices. For this purpose, organizations should commit to the effective implementation of TQM practices by adopting some quality program to accomplish CGP goals, such as Kaizen, EFQM, and MBNQA. Further, most previous studies that examine the impact of the contextual factors on TQM implementation consider TQM as a single factor without giving consideration to the possible different impacts on the different dimensions that TQM embodies. The findings in this study also address this concern by demonstrating that the organizational factors have different relationships with different dimensions of TQM. While centralization of authority can facilitate the implementation of TQM practices, it also impedes the implementation of both soft and hard QM practices. Further studies need to give more attention to the different dimensions of TQM as it is subject to the influence of contextual factors.

The results reported here argue that TQM practices are linked with supporting OC practices that are necessary for the enhancement of green performance in the health sector and introduce TQM practices as an antecedent for improved corporate culture and CGP in such sectors. This also theorizes for the first time that TQM goals of reduced waste, defects, and enhanced resource consumption are closely paralleled with quality and environmentally friendly practices in the health sector. Furthermore, the positive impact of OC on CGP has not been explored previously in this context, which serves as another key contribution by enriching existing green performance literature in the context of developing countries. This also helps in answering the question “does it pay to be green?” posed by several researchers in CGP literature, e.g., Hart and Ahuja [

152], Berchicci and King [

153], and Afum et al. [

154]. The current study also validates arguments about achieving enhancements in private hospitals’ CGP in an efficient manner by the implementation of TQM in the context of developing countries. In addition, this research supports the argument that OC mediation affects the relationship between TQM and CGP in the health sector. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this mediation effect has not been previously investigated in previous TQM and green performance studies performed in Pakistan, thus adding another key contribution to knowledge in TQM practices and green performance.

The current study also illustrates that TQM is essential for both large and medium-sized hospitals, which means that if medium-sized businesses adopt TQM successfully, regardless of hospital size, it may encourage the attainment of CGP goals. Thus, this study gives the management of medium-sized businesses trust that they can gain the same advantages from TQM as large firms. The current study also indicates that the positive influence of TQM activities is not limited exclusively to businesses operating in developed countries. If organizations successfully apply TQM activities in developing or under-developed countries, parallel results can also be obtained.

From a theoretical point of view, current research enriches in various ways the available literature on TQM, OC, and CGP. First, this research bridges the literature gap on the TQM–CGP relationship, especially in Pakistani hospitals. This research also supports the TQM proponents’ claims that successful TQM implementation can dramatically improve organizational efficiency. Secondly, this study validates the green theory, institutional theory, MBNQA, and CGP models, and explores the conceptual model’s robustness via the structure model, something which has hardly been carried out in prior studies. Lastly, this research shows OC’s function, which positively mediates the relationship between TQM and CGP, which has also rarely been estimated before.

5.2. Limitation and Future Direction

The present study also has certain limitations similar to other research. The researchers collected the data by requesting the respondents to conceptualize the questionnaire based on the firm’s actual output; therefore, this caused bias in the collected responses because it was purely based on respondents’ perceptions. Though the reliability and validity have been thoroughly analyzed, it is impossible to rule out the impact of biases completely. Therefore, the firms’ secondary data can also be beneficial in terms of extra evidence related to the relationships between TQM, OC, and CGP. Moreover, due to the spread of COVID-19, the researchers faced many constraints during the data collection phase in terms of accessibility and response rate. Secondly, the target market for data collection was based on only six cities’ private hospitals. The area of the study should be broadened to include other big cities and countries. Likewise, the lower-, middle-, and upper-level management was targeted for data collection, and this ignored the operational staff, whose view might provide more insights. Hence, the researcher can take their perception in future while further studying these factors.