1. Introduction

In a world increasingly aware of the importance of sustainability issues, specific financial mechanisms have been created for contributing to the development of infrastructure systems that promote sustainable practices. This is the case of green bonds, which are defined as those bonds whose proceeds are used only in the financing or refinancing (total or partial) of environmentally friendly projects [

1]. These infrastructure systems must be aligned with the four core components of the Green Bond Principles (GBP)—namely, the use of proceeds, the process for project evaluation and selection, the management of proceeds, and reporting—which promote integrity within this market through guidelines that contribute to transparency, disclosure, and reporting [

1].

Although no standard agreement exists on the definition of sustainable infrastructure systems [

2]. In this study, this term is referred to “infrastructure projects that are planned, designed, constructed, operated, and decommissioned in a manner to ensure economic, financial, social, environmental (including climate resilience), and institutional sustainability over the entire life cycle of the projects” [

3], p. 11. Thus, given the relation between these with other types of infrastructure systems and preserving the meaning, the term sustainable infrastructure systems (SIS) provides a broader spectrum of the interactions of this type of infrastructure with the cities’ ecosystem [

4].

As one of the most relevant green financial eco-innovations [

5], green bonds can take several forms, such as corporate bonds, project bonds, asset-backed bonds, sovereign bonds, revenue bonds, and project bonds securitized bonds, and transitions bonds [

6]. These are fixed income securities issued for companies to raise financial resources to develop SIS and other initiatives deemed eligible. In this way, investors can participate in the financing of SIS that help mitigate climate change [

7,

8]. Regardless of its type, this financial mechanism offers several advantages. For instance, ref. [

6] argue that these allow financial institutions to raise funds to expand the financial options of renewable energy actors in the development of the SIS, highlighting its environmentally friendly attributes and providing a positive marketing reputation with greater credibility of the sustainability strategy [

9]. Another of the strengths is flexibility [

6]. Any company is eligible to issue a green bond, as its eligibility is directly related to the projects or underlying assets linked to its issue. Thus, from the cost of capital perspective, the relatively low cost of green bonds could attract more companies to issue them [

10,

11].

In general, strong investors’ demand allow for an increase in the size of the issue and can improve diversification by reducing the risk of possible market fluctuations [

12]. In this regard, investors have the advantage of monitoring the progress of the projects in which they have invested, as the issuer is obliged to report on this [

13]. On the other hand, the investors could be recognized by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change as a non-state actor while meeting with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) requirements and green investment mandates [

12].

Green bonds play a pivotal role in regions where climate-friendly policy has acknowledged the need to act against global warming. In fact, the green bonds market has experienced substantial growth in recent years. Consequently, the number of public and private companies and the amount issued has been increasing in recent years [

14]. According to ref. [

15], the cumulative green bonds issuance since 2007 is USD 1.002 trillion, and only in 2020 USD 222.8 billion were raised. Clean energy, low-carbon buildings, and low-carbon transportation make up the top three sectors that have issued green bonds globally since their inception [

15].

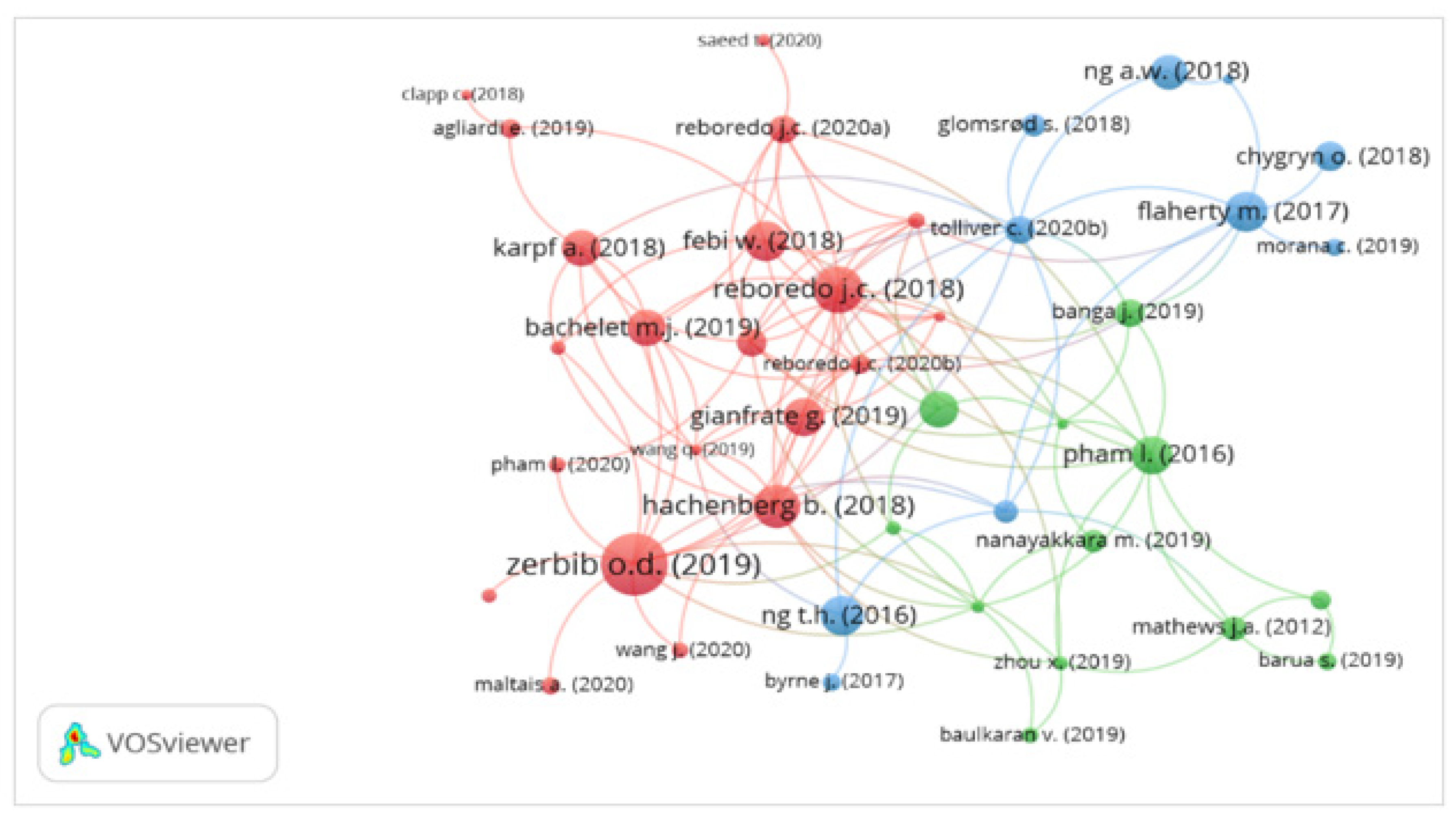

Regarding research on green bonds, different studies have been conducted. Reboredo analyzes the dependence structure of the green bonds market with other related financial markets [

16], Pham examines its volatility [

17], and Febi et al. explore the impact of liquidity on the yield spread of green bonds [

18]. Furthermore, Flaherty et al., study its convenience for funding the cost of climate change [

8] and Mathews et al. for financing renewable energy and low-carbon technology projects [

19]. Another strand of the literature has examined bond pricing. For example, Barclays analyzes the green bonds premium [

20], Zerbid discusses the effect of pro-environmental preferences on bond prices [

21], Partridge et al., and Zerbib analyze the pricing of green bonds in comparison to conventional bonds [

22,

23], and Partridge et al., and Hachenberg et al., make the comparison between green and conventional bonds in the US municipal bond market [

22,

24]. On the other hand, some studies have been carried out to evaluate the state of the green bond market and how it is a source for climate finance [

6,

8,

19,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

As can be observed from researchers’ and professionals’ perspectives, relevant studies on green bonds have been conducted. However, regardless of all the advances that have been made within the study of green bonds, we identified a gap in analyzing the dimension and determinants of the green bonds supply, specifically in the Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) region, which plays a pivotal role in the green bonds market and map of natural capital worldwide. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no study in the current literature has provided an understanding of the characteristics of this region’s green bond issues. To help bridge the identified knowledge gap, this study aims to examine the main factors defining the state of the green bonds market in LAC in order to contribute to the better financing of this region as an essential component of development and economy worldwide.

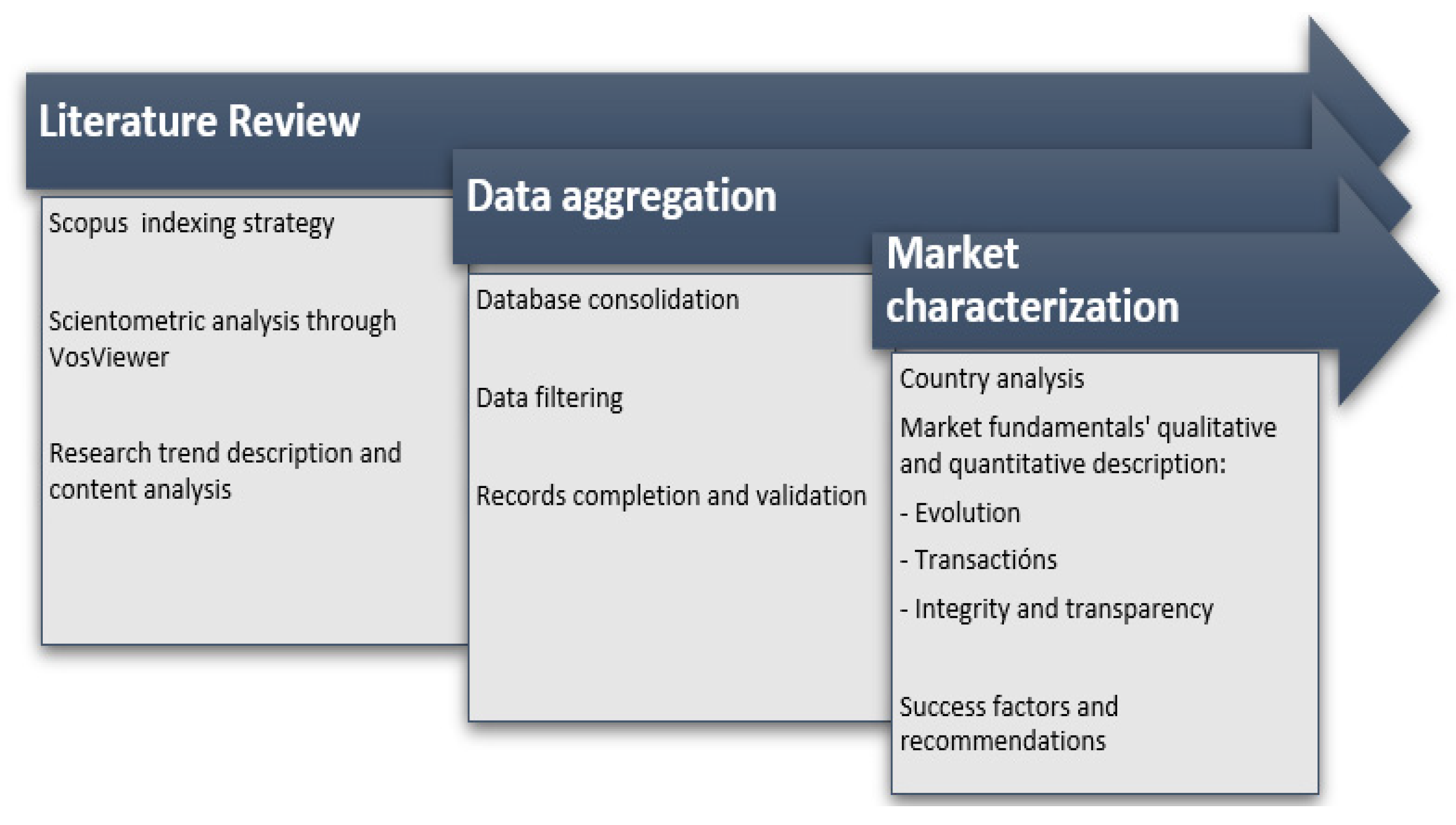

This paper makes three key contributions. First, in order to have a better understanding of green bonds, an in-depth scientometric review that analyzes the research areas, trending topics, and evolution in this arena is carried out. Second, the analysis of the green bonds market in LAC provides a road map of this type of debt mechanism issue in the region. Thereby, in order to achieve a greater understanding of the crucial role that green bonds have, the cases of the most representative countries in terms of the various degrees of advancement of the green bond market in the region are explained. This will help issuers, investors, and investment managers expand their knowledge of the opportunities available in financing SIS through green bonds and, hence, build on the experience and milestones of others. Third, this study provides significant new evidence and insights on this issue, especially in the LAC region, where research on this topic is scarce. The results could be equally valuable for policymakers in the design of public sustainability policies. Besides, the study presents the potential for future research in the field both qualitative and quantitative approaches.

The paper is structured as follows. After this introduction, which provides a context on the main elements of the study, the material and methods section is presented. Next, the literature review on green bonds is provided, followed by the results and discussion. Finally, the last section summarizes the conclusions and significance of this study, followed by further research topic recommendations.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Country Scenarios

LAC is a broad and diverse region, with 33 countries according to CEPAL [

57], which share multiple historical, economic, and cultural characteristics and show significant development disparities. Thus, even though the region is considered a whole by the United Nations [

58] as middle-income, high levels of inequality persist. Economies of various sizes coexist, from the small ones typical of the Caribbean area to medium-sized ones, such as Colombia or Peru, and even large ones, such as Brazil and Mexico. These characteristics are reflected to a greater or lesser extent in their efforts in environmental matters, the advancement of their capital markets, and, ultimately, the level of progress of their green bond markets at the date.

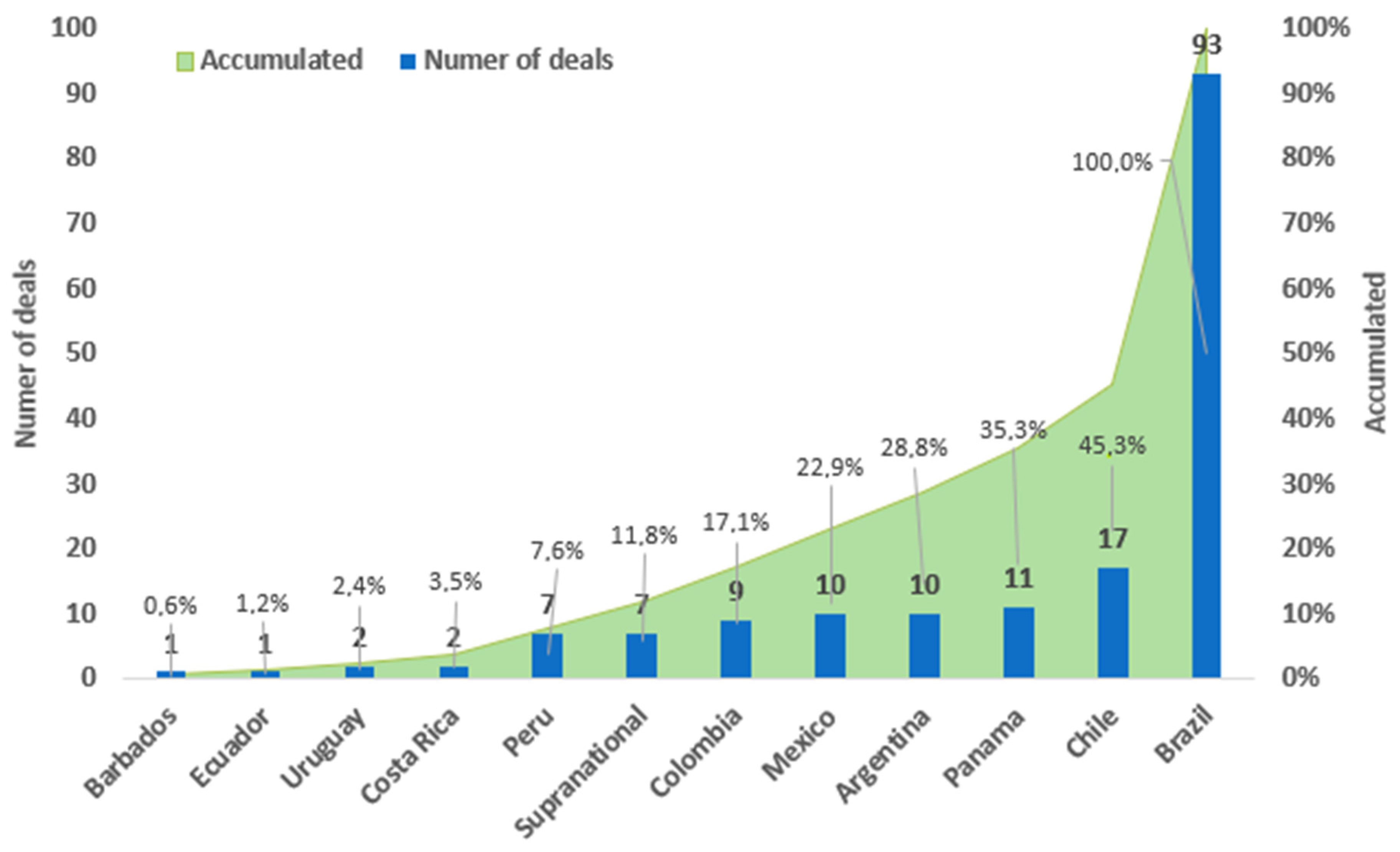

In total, 170 green bonds issuance transactions were identified between 2014 and 2020. Of the 33 Latin American countries—without considering non-independent states—only 11 (33.3%) have been active, that is, issued green bonds. Of this universe, 99 issuers have entered the region, which, regardless of whether they are single or multiple series issues, has resulted in 139 green bonds. However, it should be clarified that each bond with differentiated conditions was treated as an independent bond for all the purposes of this study since these characteristics shape supply/demand and allow the regional market trends to be distinguished.

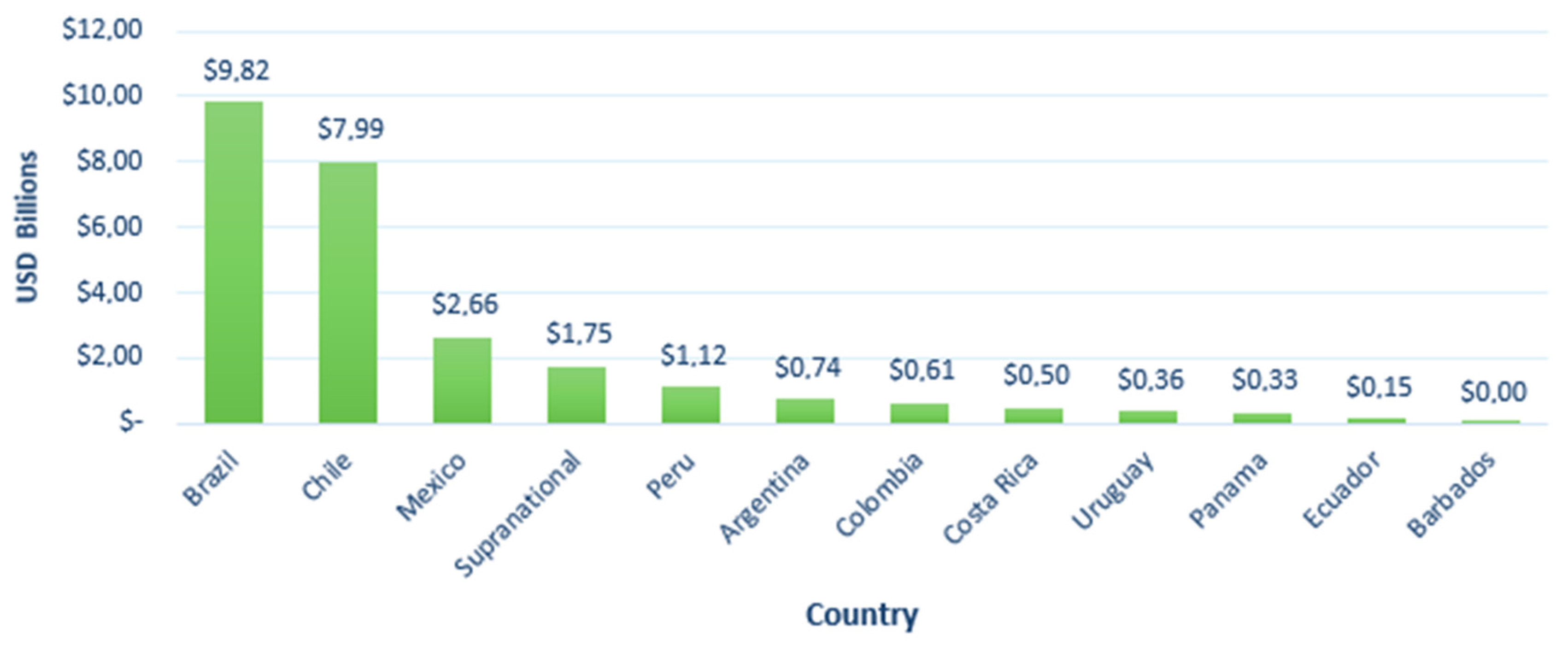

Figure 3 shows the number of green bond issuance transactions in the region. As can be seen, Brazil has been by far the most active country by the number of agreements, with around 54.7% of total agreements. Along with this, Chile, Panama, Argentina, and Mexico are the leading players. However, the situation changes slightly when considering the volume of issues and supranational bonds; Peru is included among the countries with the largest amounts issued in the market, as shown in

Figure 4. The case of Panama is particularly striking due to its small issuance size since, despite being the third country with the most significant number of agreements, it is the third with the lowest total volume issued. Overall, as of 2020 inclusive, the LAC region has issued green bonds worth USD 26.02 billion.

In general, there is a correspondence between the countries with the highest issuance and the main capital markets of the region, which suggests the necessary leverage of the development of the green bond market is robust and moderately established debt markets, but which generates a highly concentrated market and still incipient for the region since almost 80% of accumulated issuances are concentrated in three countries (Brazil, Chile, and Mexico). Likewise, there are many countries without any issuances and subregions with limited participation, such as Central America and the Caribbean area, where such instruments could significantly affect sustainability and development impacts [

59,

60,

61].

Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the green bonds market at the country level in LAC. When comparing with the offer of sustainable financial products (SFP) in the region [

53], other than green bonds, it can be observed that there is no clear correspondence since countries with SFP offerings have not entered the green bond market or only recently have they done so as Ecuador, Paraguay, or Honduras. This fact stands out since, along with policies, regulations, and economic initiatives, it is expected that the SFP offer will favor the whole range of instruments framed in sustainable finance, among which are green bonds. The following indicates the major green bonds market characteristics and issuance dynamics of some representative countries of the region due to their distinct degrees of development.

4.1.1. Brazil

Brazil is the leading economy in the region and the most developed in terms of green bonds and sustainable finance. Its first commitments date back almost to the launch of green bonds with the green protocol in 2008 and its continued efforts from the financial sector at the head of the national federation of banks towards socio-environmental responsibility in the banking sector. The development of the market has been sheltered by several alternatives and initiatives, both public and private, of the government, including the continuous measurement of green financial flows and guidelines on best risk practices and disclosure of ESG matters. This has generated a favorable ecosystem, which makes Brazil the undisputed leader in green bond issues and puts it ahead in SFP offerings by banks and financial institutions.

Among all its milestones, the guide for the issuance of green bonds in 2016 stands out, which was based on the existing regulations and took advantage of it so that the same actors arranged the incentives, that is, the interest of investors and issuers, and also had the participation of various actors such as regulators, financial institutions, potential issuers, investors, external reviewers, and civil environmental organizations. Besides, Decree 10.387/2020 is mainly expected to boost the development of renewable energy, low carbon transportation, water, and sanitation projects.

Such issuing guidelines have been successful. Although growth was expected due to the momentum of green bonds globally, these guidelines have been recognized as the key point for developing this market in the country. Once its development began, significant issuances were expected in renewable energies, forestry, and agriculture, which was materialized for the first two, but not so much for the last since the accumulated issuances from agriculture represent close to 1% of the total. It should be noted that the national guidelines are voluntary and focused on the aspects of external reviews and reporting during the life cycle of the bonds. This example of guidelines for sustainable finance shows the role of financial institutions in the region and their potential to make visible and give rise, as natural actors, and benchmarks of the capital market, to the development of green bonds in each country.

From Brazil, it is emphasized that, in SFP, the participation of products destined for agriculture is essential, while in green bonds, the predominant sector of issuers is energy. Of course, agriculture, although one with scarce participation, has been growing. It also highlights that the second sector with the greenest bond issuers is forestry, which is in line with its large pulp and paper industry. Similarly, the predominant role of publicly-owned banks in Brazil in the SFP offer is not reflected in the participation of green bonds, with participation only by BNDES. This suggests that such institutions obtain the resources for such instruments from generic funds and not of specific destination as is proper with green bonds. Brazil is responsible for 37.7% of the issuances in the entire region. It is the one with the broadest market with the most remarkable diversity of issuers (93). However, at the same time, it is also the one with the highest number of recurring issuers. Most of the issues come from non-financial corporations (93.5%), and its most active year was 2019.

Another aspect to highlight in Brazil and possible replicability in the region’s countries is investors’ incentives to demand sustainable instruments such as green bonds. Specifically, the case of incentivized debentures in infrastructure, established by law 12,431/2011. These are fixed income securities on infrastructure projects considered a priority for the country and grant investors tax benefits on their income. This instrument has become the most convenient mechanism for raising funds in the sector, where investment opportunities in projects with sustainable attributes are urgent both in Brazil and the rest of the region. One element that should be worked on is reducing the limitations to municipalities or local governments to access capital markets [

62,

63] since these entities have great potential for financing climate change adaptation and mitigation projects through green bonds.

4.1.2. Colombia

The country is halfway in both the size of the economy, ranking fourth, as well as in the development of green bonds (seventh by volume issued), and with great growth potential if one considers the policy efforts and initiatives advanced and that is the country in the region with the highest proportion of traditional bond issuers fully climate-aligned [

63]. Colombia began its development in sustainable finance in 2012 when its green protocol is released. In 2016, when the first green bond issue took place, the same entity, the national banking association, published a set of guidelines for executing E&S risk analysis to boost issuances. As in Brazil, the issuances with the most significant impact have been directed from the banking sector.

Thus, recently and in search of paving the way to increase this market in the country, the financial regulator (Superintendencia Financiera (SF)) has undertaken necessary actions, among which the issuance of a Good Practice Guide for issuing green bonds, as well as External Circular 028 stands out of 2020, where green bonds are defined. An entire regulatory framework is created against this instrument, something that no other country in the region has to date and provides momentum and clarity to all market players. Likewise, guidelines have been published for the preparation of ESG reports from issuers. On the other hand, three critical measures to attack barriers to the growth of green bonds have been implemented by the SF. Firstly, it is being developed its own taxonomy for sustainable finance. Secondly, as of April 2021, it is obliged to pension funds to include an ESG risk analysis and climatic factors in managed assets and investment decisions [

64]. Lastly, in 2021, the Ministerio de Hacienda (Ministry of Finance) launched the first sovereign green bond issuance framework. This is expected to finance expenses associated with a green portfolio to contribute to Colombia’s environmental objectives and international commitment. Furthermore, information on eligible green projects as well as categories and their performance indicators were published. The portfolio projects include 27 investments of up to USD 2 billion, which are classified into six categories: water management, use and sanitation, clean transportation, ecosystem services, and biodiversity protection, non-conventional renewable energy sources, circular economy, and sustainable agricultural production adapted to climate change.

In this sense, an increase in issuances and market activity is expected, supported by greater clarity in the issuance process, greater transparency, the indirect drive towards green mandates for institutional investors, and the certainty provided by an increasingly integrated ecosystem. Regulatory measures worthy of imitation by the rest of the issuing countries in the region.

Colombia shares characteristics in terms of volume and degree of market development compared to other countries that already have experiences in the market, such as Argentina, Peru, and Costa Rica, but still need to reach the maturity and volumes of Brazil or Chile. Regarding the type of issuer, Colombia is, unlike the rest of the countries with several issues, dominated by financial issuers (financial corporate and development Banks) with 66% of the agreements and 82.85% of the total volume, and it also has a low concentration of issuers since only one company (Bancolombia) has issued on more than one occasion.

The most significant activity by the number of deals was 2020 with the debut of two new issuers, ISA and Banco de Bogotá. ISA’s issuance is significant as it was the first green bond issue by a company in the real sector in the country’s public securities market. Regarding the use of funds and due to the predominance of financial issuers, the use of funds is, on many occasions, multiple. The sectors most addressed have been energy, buildings, and industry. However, there is insufficient attention to the sectors of agriculture and infrastructure (transport, sanitation, public facilities such as hospitals and schools) that present great potential for reducing CO

2 emissions along with the possibility of jobs creation and the reduction in the development gap due to the historical abandonment of these sectors [

63]. An example of these is the road toll concessions to private investors, with which the traditionally timid market for project bonds in the country has grown, and progress has been made in the road infrastructure gaps, which at the same time present an enormous possibility to be advanced with sustainability criteria that make them eligible as green projects [

65,

66].

4.1.3. Barbados

Barbados has a single issuance of green bonds. This took place in 2019 and was a private placement in local currency equivalent to USD 1.5 million over four years and a fixed rate by a financial issuer, Williams Caribbean Capital, to install solar roofs in commercial buildings. This has been not only the first green bond in the entire Caribbean but also the first to receive certification under the Climate Bonds Initiative scheme, thus highlighting not only its novelty but also its rigor and contribution to the goal of reducing dependency on fossil fuels that exceeds 90% in the country. This milestone for the Caribbean region, together with the awards for the transaction by clean energy unions and credit programs to the country by the IDB to promote energy efficiency and renewable energy in the country, mark critical points for the future development of the sector and allow new issues to be foreseen by private parties. In this scenario, financial entities would be highly beneficial since the central government aims at promoting these projects in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the country [

66].

As is recognized in the literature and has already been mentioned, there are limitations to developing countries’ advancement of green bond markets. On the one hand, an adequate minimum infrastructure of the fixed income market is a requirement for the issuance and trading of green bonds, and on the other, there is a barrier in terms of the attractive issue size [

67,

68,

69]. With these barriers in mind, financial actors related to such markets and greater attracting capacity are favorable in emerging regions such as LAC. This is the case in the Caribbean where projects do not reach the sizes expected by large investors, and companies are still far from the capital market, thus setting the conditions for financial actors to raise funds via green bonds and promote sustainability in multiple sectors through loans or other green SFP, according to their national reality [

53]. These conditions of energy dependence are also typical of neighbors in the region, even with superior fixed income markets and higher environmental risks that do not yet issue green bonds, such as Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, the Dominican Republic, and the Bahamas. Another interesting possibility would be the joint issuance of a sovereign/supranational bond between several Caribbean countries, allowing more significant and attractive issues.

On the one hand, this can lead to better financial conditions and, on the other, to undertake joint projects on environmental problems and opportunities of impact and interference on common resources throughout the Caribbean region [

63,

70,

71]. Most notably, Central America and the Caribbean face greater vulnerability due to frequent natural disasters and subsequent food crises [

58]. This high-risk profile of many states creates enormous opportunities to obtain resources and generate adaptive capacity. Thus, in addition to the energy sector, blue economy projects framed in water management and ocean activities essentially respond to their sensitivity to climate change. This category of projects is both imperative to address and capable of offering attractive returns [

63].

Barbados has, although small, a fixed income market. Notwithstanding, public debt is the one that dominates the market by volume issued, the number of private issuers is more than the public ones. This condition is shared to a greater or lesser extent by other countries in the Caribbean area. It can be considered, along with strengthening the stock exchanges of the said region with initiatives such as the constitution of the Caribbean Exchange Network, indicative of the interest of private parties for participating in this market. Likewise, it confirms the great potential for growth in the coming years under a scenario of close and constant coordination and cooperation among the stakeholders, both at the country and regional levels.

4.2. Market Evolution

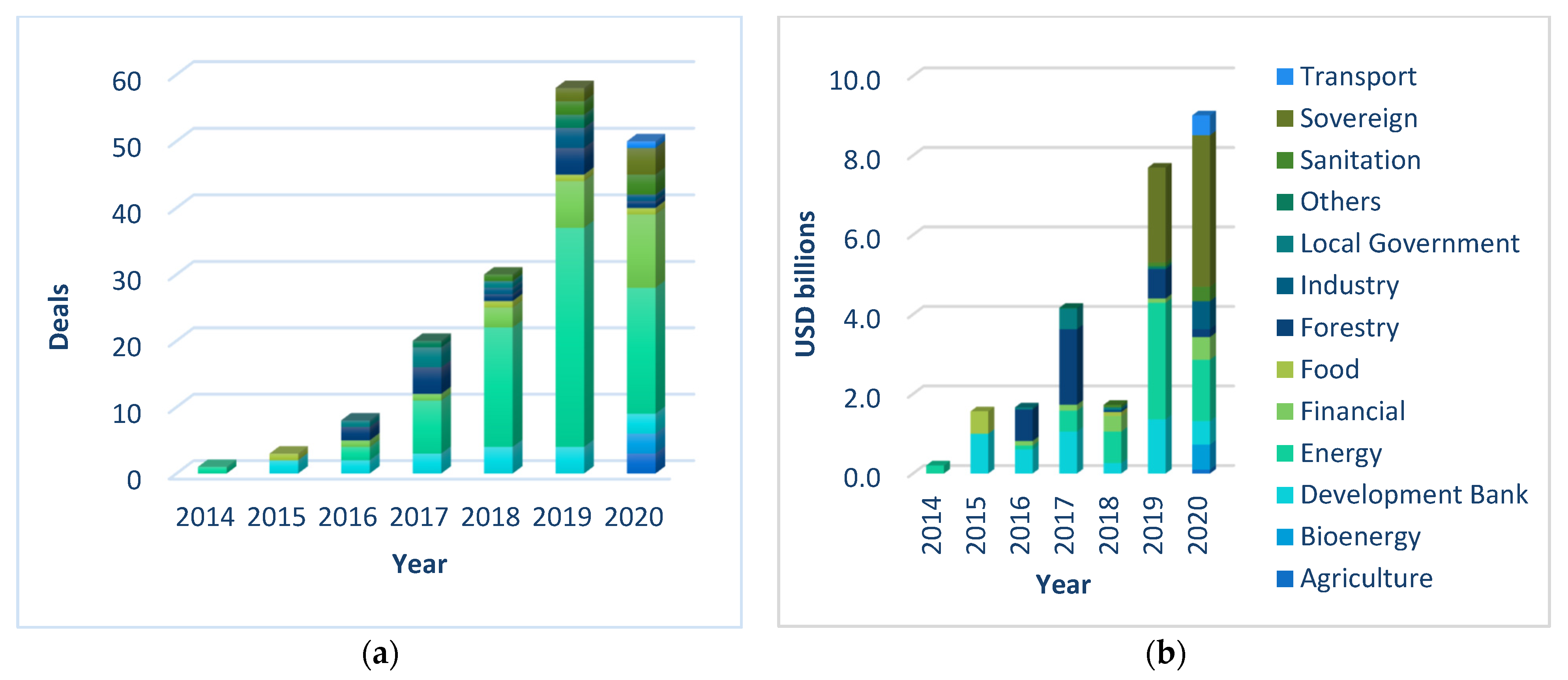

The green bond market in the region has grown every year since 2014, both in terms of deals and in volume issued (except for 2018). Of the USD 204 million issued in 2014 with the first issuance of Energía Eólica in Peru, it has reached USD 9.008 million issued in 2020, which means a growth of 44×. This development has been thanks to an average annual increase of 1.88×, notably superior to the global average of 1.41× and slightly lower than that of emerging markets at 1.97×. In this way, 2020 has been the best year in terms of volume issued.

As shown in

Figure 5, these growing trends have not been extended to issue sizes, which is noticeable in between 2017–2018 or 2019–2020, where despite the increase in agreements during the year in course, the money placed presented a fall. In fact, after the resentful year 2018 for the green bond market due to poor market conditions and external shocks due to political instability and deteriorating global economy, the average size of the issue, although growing year by year since then, has not yet managed to return to the previous levels and stands at approximately USD 153 million. It is important to note that in 2019 and 2020, the market was driven by sovereign issues as well as energy and financial sectors. For example, Eneva (Brazilian Energy Company) issued a green bond for USD 178 million as a two-tranche deal in 2020. Besides, it also stands out that, in just one year (2015), and not even in 2019 or 2020 with sovereign issues, an average deal size of the type “benchmark size” was obtained (+USD 500 million), a characteristic that only 22 bonds have had (13%).

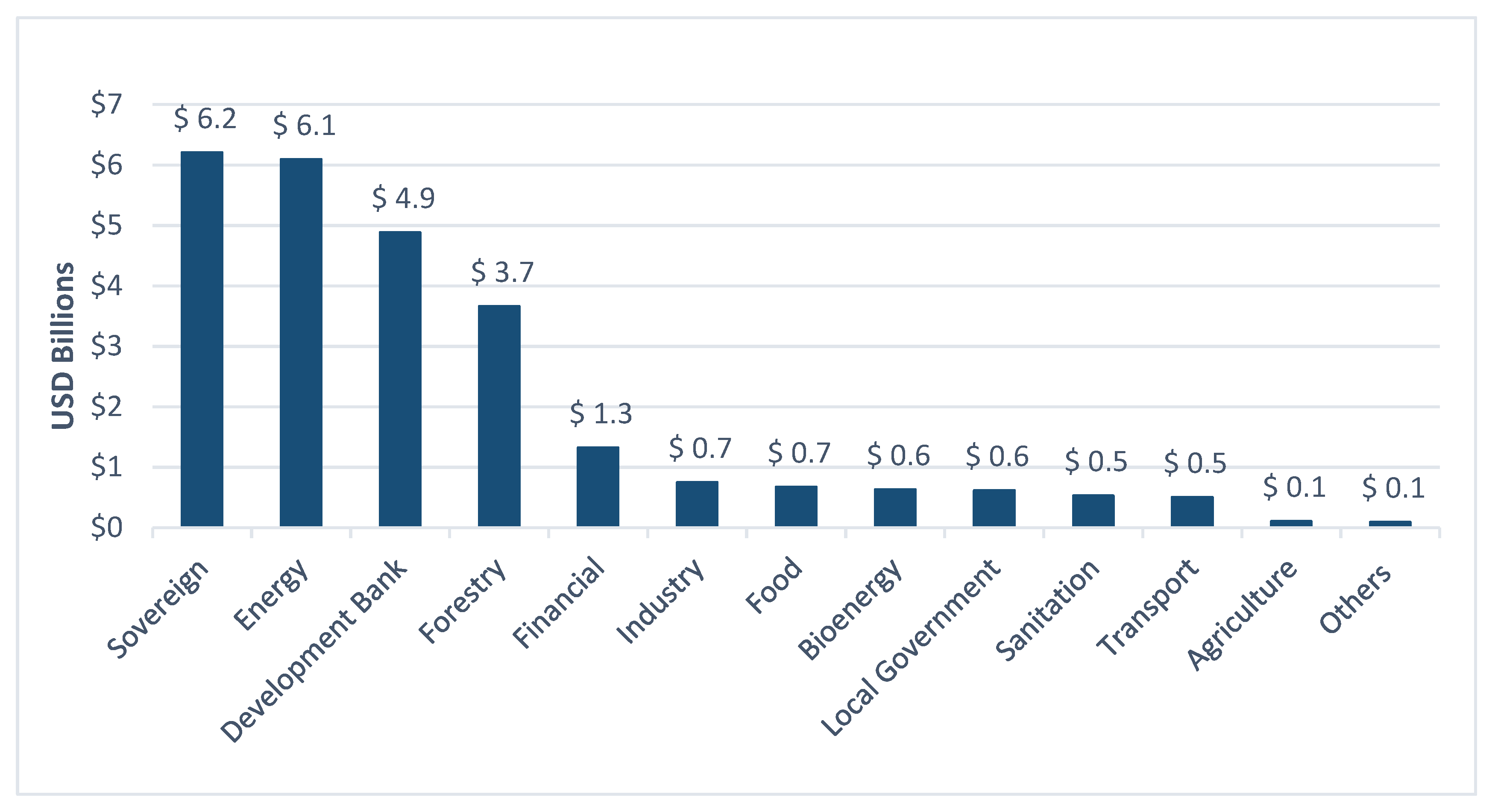

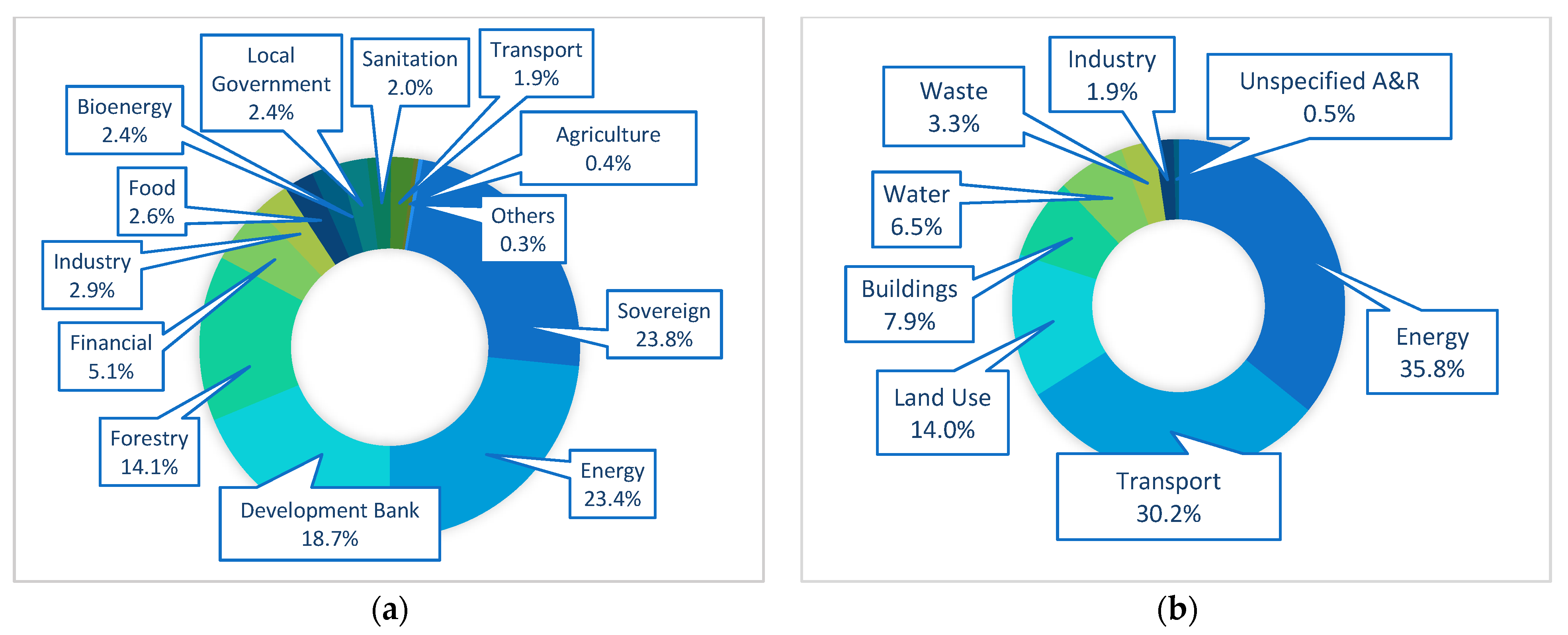

On the other hand, when comparing the volumes issued by sector and excluding the sovereign issue category, the energy sector is noted as the most significant contributor, as indicated in

Figure 6. Still, despite the few sovereign issues, it is remarkable that they exceed the amounts issued by the 81 transactions in the energy sector. This indicates a great state commitment and impulse to green activities to be financed with these funds. The signaling role of this type of transaction is ratified and an opportunity to position itself in the international capital markets for those central governments that opt for these instruments. For example, Peru, Mexico, and Colombia have announced potential sovereign green bond issues. However, they have not yet materialized. Taking Chile as an example, it would be positive for these and any other countries in the region to give impetus to green finance and growth of this market at the country level like few others. Likewise, they serve governments as the perfect opportunity to demonstrate their environmental commitment beyond rhetoric to the international market and community. In terms of ambition, in many cases, commitments fall short or are questionable, according to the most recent progress report of the UN NDCs [

63,

72].

Comparison of the issuing sectors and the use of funds reveals relatively high correspondence between them for most categories. In other words, a given company issues a green bond and invests, the vast majority of the time, in projects and activities within the same sector. Proof of this is the energy sector, the leading emitting sector in terms of emissions and use of proceeds. This dynamic is also observed in the categories with less participation, such as forestry, industry, and sanitation. The second and third place by use of funds is shown in

Figure 7. However, the correspondence with the issuing sector is not observed so clearly since neither the transport nor construction sector appears as key issuers neither by volume nor by the number of agreements as evidenced by the figures. From this, it follows that the resources deployed in such categories come from financial and sovereign issuers, which privilege them in their loan and project portfolios, respectively. For instance, issuances in Colombia from Bancolombia and Davivienda were mainly used in residential real estate projects and energy efficiency. The case of the Chilean sovereign bonds of 2019, where 99% of the resources were towards clean transportation and sustainable public buildings, with Line 7 of the Santiago Metro as the primary project representing 58% of the portfolio [

73] confirms and explains this dynamic in the region. In this way, Chile becomes the first country in issuing a sovereign green bond in the region.

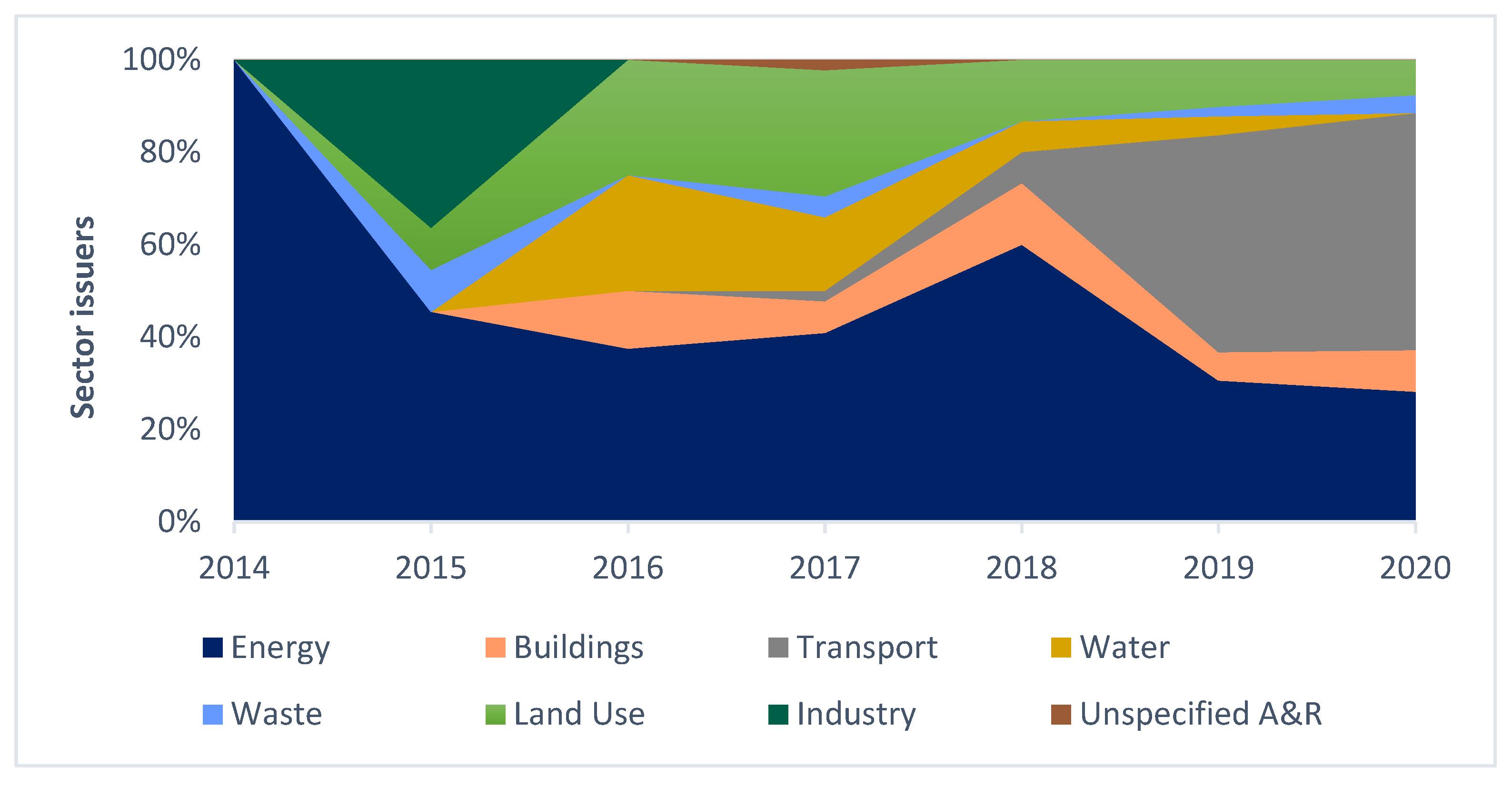

Regarding the evolution of issuers, the balance is positive since an increasing number of sectors are participating, going from 2 in 2015 and 6 in 2016 to 10 sectors in 2020.

Figure 8 shows the evolution of the use of funds to the regional level. With the market’s advance, the energy sector’s contribution has been reducing and, to a lesser extent, land use due to the increase since 2017 and intensively since 2018 in the transport category. However, there have not been many agreements, they have been extensive. The water and buildings sectors are slowly gaining ground, while industry has not reappeared since 2016.

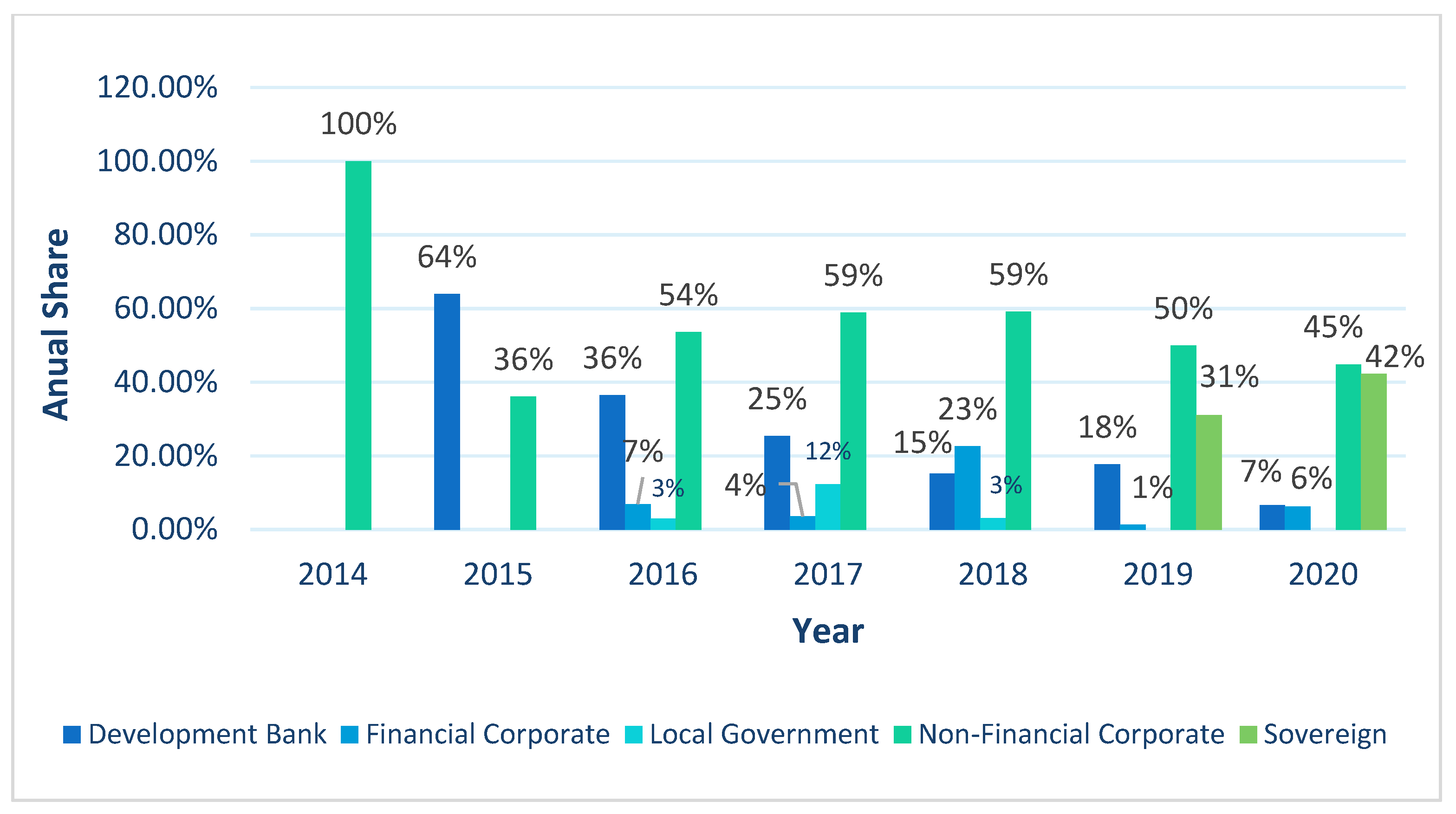

Finally, regarding the dynamics of types of issuers in LAC, there is a clear decreasing trend in the participation of development banks, offset by the position as leader of non-financial corporate issuers maintained since 2016 on average over 53% as shown in

Figure 9. This behavior can be reasonably interpreted by the fact that the initial issuances of development banks were largely to make visible and set the tone for the rest of the market, in its bulk non-financial corporations. Sovereigns barely made inroads in 2019 and 2020 with Chilean issues, although few have been of significant amounts to the point that they represented 42.32% of issues in 2020. Financial issues, except for 2018, have had timid shares without never exceed the 7% annual quota, and, albeit they were the ones that grew their issuances the most from 2019 to 2020, increasing by more than five times, these together with the sovereigns are, due to their catalytic potential, the issuers called to grow in volume and number of agreements.

On the other hand, local government issuances are concentrated almost exclusively in 2017 with 83%, and the participation of only Argentina and Mexico is of concern. There is a large gap to be filled as these organizations have vast investment opportunities in sectors such as clean transport, water, and waste management, green buildings, and small-scale renewable energy. Furthermore, these instruments are an alternative to the often insufficient budgets of these governments. Finally, a good performance is observed during 2020, because despite the decrease in the number of agreements as well as the global market, the general volume increased (1.17 times the previous year value), and non-financial corporations maintained their volume of 2019, a positive development given the situation caused by the pandemic, especially in private actors [

74].

4.3. Transaction Determinants

The set of issues carried out so far supposes an average maturity period of 13.47 years, constituting long-term issues. In this value, the effect of sovereign bonds and the energy sector by non-financial corporations is key since they often have terms of more than 15 years. The most extended term issue has been for 60 years by AES Gener in Chile. The one with the shortest term for its part has been Argentine AES with 0.75 years. Thus, 36% of LAC issuances are in the 5–10 years band, followed by 10–15 years with 26.29%. However, at the country level, these proportions change significantly from one to another. Examples of this are Chile, Panama, and Peru, where the dominant band is 10–15 years. Such composition is in line with what is observed in other green bond markets such as Europe. There, approximately 70% of the green bonds issued have a term of ten years or less, 28% have terms of up to 5 years, and 41% between 5 and 10 years [

75]. Medium and long-term issues are typical of public and private non-financial companies, while financial institutions favor bonds with shorter maturities (maximum five years). Sovereigns, for their part, tend to opt for long-term bonds (15 years or more), i.e., periods that are very conducive to infrastructure asset development projects and are well received by institutional investors [

61].

In respect of the currency of issue, it is considered that large issues, in which international investors are usually targeted and classified as sustainable, are carried out primarily in dollars. On the other hand, local currencies are used for smaller ones, and that is why local investors acquire those. Such a trend is observed in the region. In this case, 62.35% of the agreements have been in local currency and 37.64% in foreign or hard currency, where the US dollar (34.12%) is clearly dominant against the euro (2.94%); however, by the amount issued, foreign currencies lead with 75.97% of it. The most widely used local currency, consistent with the previously mentioned number of agreements, has been the Brazilian real. By country, local issuance, discounting the issuance of Barbados, is privileged only in Brazil and Colombia. In the latter, all agreements have been carried out in COP, and none have been benchmark-sized. For its part, the dollar is the preferred option for all types of issuers, varying in proportion to each one. In particular, corporate financial issuers are those who exhibit a more balanced share between the different currencies.

Compared to the type of rate chosen, the analysis reveals 92% of transactions where the agreed rate was reported, 43.9% were at a fixed rate, and 56.1% were at a variable one. The variable rates have been mainly tied to the price indices, such as the CDI in Brazil or the IPC in Colombia. This protects investors and is consistent with the aversion generated due to the inherent inflation risk, which is fundamental in emerging countries such as LAC. These agreements are observed both in countries with acute inflation episodes and those with relatively stable prices.

In line with the above, the available data shows that the decision to issue domestically or abroad has been relatively even, with approximately 48% of local issues, which shows an ambivalent taste in the region for local and foreign investors. In this sense, the role of local institutional investors is confirmed due to their financial capacity, acceptance of smaller attractive minimum project sizes compared to foreign institutional ones, and given that most of the green bond issues in local currency are previous steps towards more developed and robust markets. Cases such as Mexican pension fund managers (Afores) in the green issue for the construction of the Mexico City airport indicate the match generated.

Another element inherent in the structuring of bond transactions in the region, such as the number of series, shows, with more than two-thirds of the volume and agreements, the predilection of issues for a single series over multiple tranches and differentiated issues conditions. Likewise, for the different terms and issuers, a clear tendency is identified for frequencies of semi-annual coupon payments (50% of agreements) followed by annual payments (11%). Disbursements of lower frequencies have marginal participation and are associated with the efficient management of the projects’ cash to which the funds are directed. There is great diversity regarding the amortization schemes, and a precarious disclosure of such information was found, but what is observed is that they usually correspond to the aforementioned interest payments.

The average size of emissions for LAC has already been mentioned; however, they differ over time, and each sector and issuer has contributed differently. The trend has been for sovereign issuers to be by far the largest and most significant transactions, notably impacting LAC’s value-added trade despite the few transactions to date. The largest emissions come from the government, transportation, forestry, and development bank sectors at the sectoral level. On the other hand, the smallest are located in agriculture, logistics, and technology, particularly in corporate financial issuers. It should be noted that, although the market has grown, the types of projects have not varied much, so that the sizes of the operations have not experienced significant variations. It is observed that, although the average issue size is barely growing and has not yet reached levels before 2018, the behavior of the proportion of deal size is encouraging given that the quota of medium-size and benchmark-sized deals has been growing steadily in recent years. Such tendency translates into 11% of transactions in the 0–100 million range, 33% in 100–500 million, 44% in 0.5–1 billion, and 12% greater than 1 billion. This in comparable to the pooled outlook for emerging markets with shares of 6%, 37%, 29%, and 25%, in each range, respectively, and even LAC slightly surpass it in the +500 million range. It reflects the result of efforts made to drive market growth in the region and follow global trends. This also supports the suitable position of the LAC region to maintain and achieve a significant contribution in the global project bond market, especially in the energy and infrastructure sector [

65,

66].

Finally, it cannot be disregarded that multilateral financial institutions, such as the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and International Finance Corporation (IFC), particularly their climate finance teams, have played a pivotal role in several agreements in transactions. Their actions are part of a tendency for institutions to act either as sole investors or as the leading structuring agents. Behind this role is to create a market and position first-time issuers for future issues and better trading terms. Examples of this are the Bancolombia green bond issuance, where IFC acquired all of it, IFC’s advice to Banco Pichincha in Ecuador, and the IDB to Chile’s first sovereign green bond.

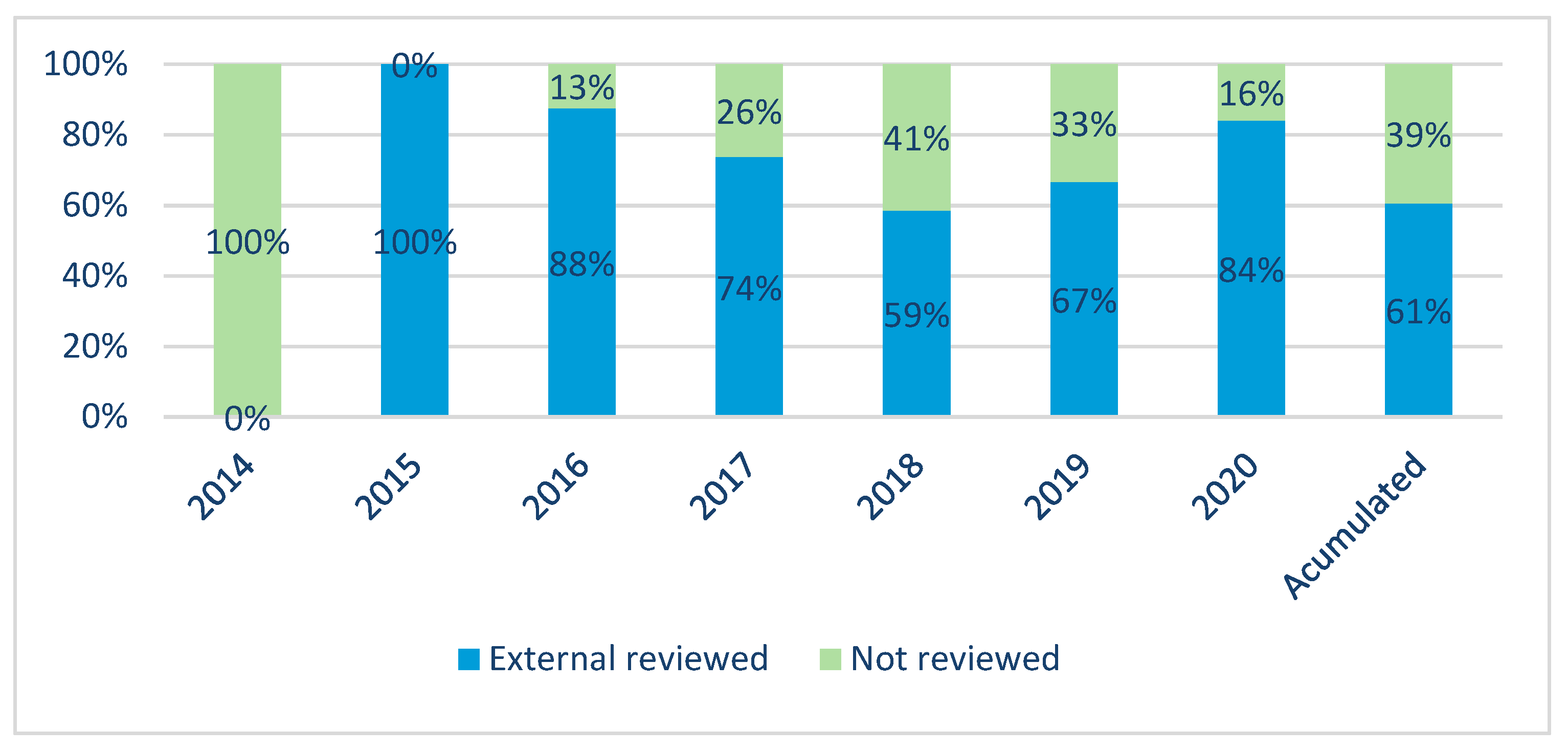

4.4. Instrument’s Transparency and Integrity

At the consolidated level, 72.02% of the transactions were externally reviewed, which translates into approximately USD 23.7 billion or 91.20% of the amount issued validated in some way under the external review figures contemplated by the CBI. In emerging countries such as LAC, no effort to make equity markets more transparent is fruitless. In the particular segment of green bonds besides general corporate disclosure measures, it is essential, beyond promoting external reviews, to validate possible links or conflicts of interest between the verification companies and their evaluation. Although with regional advances in corruption, the region continues to be perceived as one of higher incidence of corruption [

76]. The relative failure of initiatives in the financial markets of LAC, such as the case of the second markets oriented towards the inclusion of SMEs in them and promoted in countries such as Brazil and Colombia, have shown how information asymmetries persist as an essential barrier between the different actors [

77]. It is crucial to combat this perception. Adoption of the TFCD recommendations and guidelines from organizations such as the CBI or GBP, and, whenever possible, making them a requirement for issuance by regulatory bodies, is the best option in the current scenario.

In

Figure 10, the evolution of the share of externally revised green bond issues in LAC since the first agreement is shown. Larger issuers are generally more likely to report. In line with world trends, the proportion of reports depends on the quantity issued and is more usual in the medium to long term. In addition, countries with larger green bond markets tend to have higher levels of information [

63]. Despite this, there is no evidence of such behavior in LAC between 2014 and 2017. However, there is an increasing trend in reviews after 2018. This can be explained by the TCFD recommendations issued after 2017, the strengthening of issuance requirements by national regulators, and the greater adoption since then of GBP. All these trends are expected to continue. One case that draws attention is that issuance in Ecuador to date, which despite being recent and coming from a financial corporation, did not report having an external review.

To battle another of the barriers identified in issuers, such as fear of damage to reputation due to being perceived as green-washers, the different reports and dissemination measures for both uses of resources and impact are especially key. With them, visibility of the results is given to other actors such as the local and international community. It allows corporations and governments to account for the results of the projects in advancing their commitments to sustainable development and climate change. In other words, it allows them to align with what is expected of the policies of those who issue green bonds today, that is, to reflect the strategic consistency of sustainability.

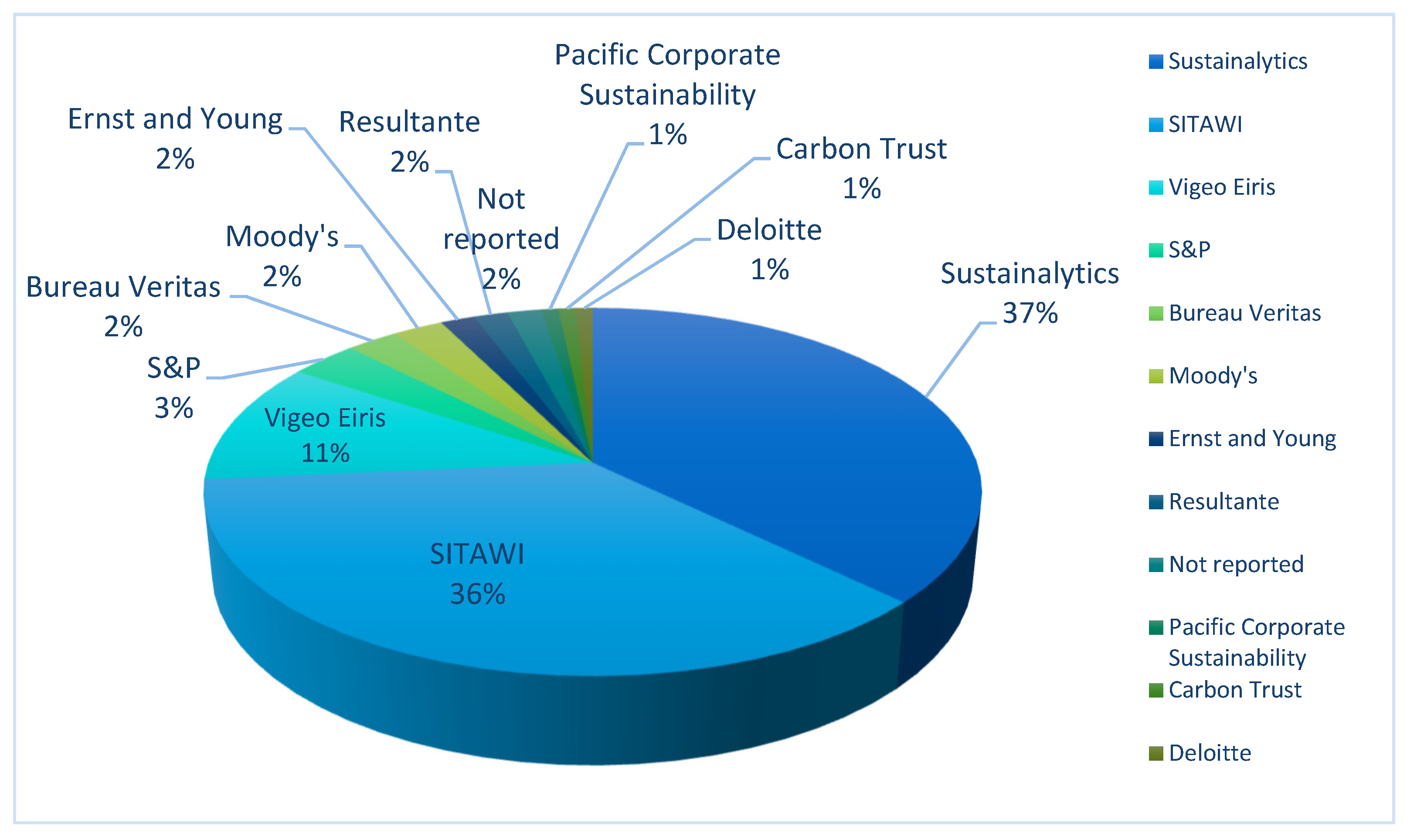

Finally, in terms of external revision providers, despite the diversity, there is a high concentration in the region, as indicated in

Figure 11. Sustainalytics and Sitawi leads the revision business, the latter mainly driven by its position privileged in Brazil, where most agreements have their evaluations, followed by Vigeo Eiries and Standard & Poor’s. Even still, a good part of the issuances do not report details in this regard, and alike those who have them must improve their disclosure for the access of the interested parties. In particular, support for platforms that gather information from these instruments in the region, such as the GBTP, is essential.

4.5. Success Factors and Recommendations

As a result of the evolution and current state of the green bond market in the region, it is possible to identify some success factors and recommendations for its development that are susceptible either to deepening in the countries where they have arisen or to replication in other countries and even on a supranational scale. These are mentioned below:

Sectors initiatives and market agents such as stock exchanges, commission agents, and companies that have already issued help significantly boost the market growth. Training and outreach programs undertaken by financial regulators or banking associations are a great way to do this, such as Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia.

It is suggested to consolidate guarantees and bolster government agencies and development institutions that improve project risk-return profiles. These represent an indisputable step for the involvement of issuers and investors by improving ratings and terms as well as ultimately raising confidence.

Through tax incentives and training with market players, we propose to promote the creation of verification entities at the local level that begins working with smaller projects and can become cheaper alternatives for external review in the medium term. Such a purpose would be highly effective by relying on the experience and support of institutions such as CBI, Sustainable Banking Network, and the International Capital Market Association. Such verification entities may not even be dedicated to green bonds but to measure associated sustainability issues such as carbon footprints of supply chains or product life cycles, a flaw not addressed but recognized as an imperative within the comprehensive sustainability approach. The perception of issuance benefits that do not offset the costs and complexity of such reviews and internal monitoring makes it necessary to work on two fronts. On the one hand, prioritize what the data suggest in the discourse; that is, the issuance is made as a strategic element of the companies and not only to save and compute costs in a business as usual logic. On the other, seriously evaluate the possibility of supporting subsidies or tax benefits by hiring reviews, evaluations, and external consultancies associated with the issuance.

In general, potential projects of small, medium, and even large companies in the region do not reach the level required for a successful issuance in the primary market. Given this and the existing opportunities in the sectors and SDGs with greater lags, a viable and already observed solution is channeling bond funds to small projects through investment funds or banks that operate efficiently in the fixed-income market.

There is a very interesting possibility of replicating incentives on green bonds income to investors, as in Brazil’s debentures. The proven success there, the important positive association recognized between institutional factors such as tax incentives and the development of green bond markets, and the characteristic shared by much of LAC in terms of deficits and poor condition of essential infrastructure position them as a mechanism of great value. Furthermore, taking into account the particularities and priorities of each country, the benefits could vary and could be applied in specific sectors, whether related to infrastructure or not.

To avoid that projects susceptible to green issuances are seen as very complex that dissuade those interested. On the contrary, for they to appear as a gradual and affordable possibility, it is essential to incorporate taxonomies at the country and, hopefully, the regional level. These taxonomies make it possible to demarcate the difference in its economic composition, polluting profile, and character in development and environmental awareness for developing and even emerging countries with a superior degree of progress in such areas.

A fundamental step towards the growth of the green bond market in LAC should be the obligation of external review, its publication on websites, and verification of expertise by verifiers as it has been implemented in Costa Rica. This, together with indirect promotional actions such as the inclusion of badges in the ISIN or identifier in the transaction and information platforms, contributes to its visibility and integrity, crucial to investors’ perception that there are not enough financially attractive green investments opportunities [

61].

The global contingency of COVID-19, of significant incidence in LAC, provides great opportunities for new issues that encourage government recovery plans. At this point, green sovereign bonds emerge as a great opportunity for the expected sustainable recovery projects of environmental and social impact, naturally susceptible to financing with green, social and/or sustainable bonds. As the Chilean case showed, green bonds of this type have enormous catalytic power in the economic greening movement and provide the certainty that investors expect about a real long-term commitment of public policies in the face of ecological investments and climate change.

5. Conclusions

The green bonds market in the region has experienced remarkable growth from its first and only issuance in 2014 of USD 204 million to USD 9.008 million issued in 2020, which means an outstanding 44× growth. An improvement has accompanied such expansion in terms of diversity of issuers, sectors, and size. Despite this growth, it should be noted that there is little participation by the countries of the region since only one-third of LAC has issued green bonds, and 80% of accumulated volume issued is concentrated in three countries (Brazil, Chile, and Mexico). This shows the correspondence between the countries with the highest issuance and the main capital markets of the region. Likewise, Central America and the Caribbean area stands out of all countries without any issuances and subregions with limited participation. Such instruments could significantly affect sustainability and development impacts, especially renewable energy, blue economy, and water management sectors.

The analysis of the evolution and current state of the green bonds market makes it possible to identify socio-environmental awareness, institutional green mandates, investors motivated by fiscal stimuli in income from green instruments, the momentum for the redesign of corporate strategies to long-term oriented to stakeholders and processes, either of intensive machinery replacement or expansion, mainly in brownfield projects as the main driving forces of the market. On the other hand, energy, transport, and land-use sectors stand out as the leading sectors by use of proceeds. It is also worth highlighting the case of the agriculture sector, which although with a still-low percentage in the total, the number of agreements has been growing. It shows the region’s great potential and correspondence with the highest emissions and opportunities for investments.

Essentially, the most active issuers have been concentrated in energy and financial sector (corporate financial and development banks), but the trend is towards greater participation by sovereigns and non-financial corporations, especially forestry enterprises. Although the financial issuers (corporate financial and development banks) have not been the leaders at an accumulated level and their direct participation in the market is declining, they are fundamental in LAC countries. Most of them are small- or medium-sized economies with project sizes below the interest of institutions and foreigners (attractive minimum issuance size). Thus, these financial institutions can capture resources and channel them using financial mechanisms such as credit lines to such companies and projects [

61].

In the market dynamics in terms of issuance sizes, a follow-up of the global trend of greater participation of medium-size and benchmark-size agreements is observed. Thus, the region is above the emerging global region, with the 500 million–1 billion range being the predominant by volume in 2020 and confirming its good position to lead the advance among them. It is essential to reproduce the best practices observed both in leading countries and those with the most promising initiatives at the regional level. The actions implemented in Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Chile, and Barbados deserve special attention. Several of the LAC countries’ institutional and development characteristics provide a great convenience for replicating the success factors and working together at a supranational scale in initiatives such as the development of regional taxonomies and the consolidation of transactions’ information platforms such as GBTP.

Regarding the transparency and integrity of the market, recent years show an improvement in this aspect supported by the adoption of voluntary international guidelines (TFCD, CBI, GBP) and mandatory requirements by some regulators. Even so, it is imperative to improve the disclosure of reports and general transactional conditions. Given the barrier posed by the extra disclosure efforts of issuers, the way forward should be oriented on two fronts: raising awareness of the strategic nature of issuance of this type of bond and developing subsidies for contracting reviews and external verifications that arise as an additional cost.

On the other hand, it was evidenced how development financial institutions are playing a pivotal role in boosting the green bonds market. This is, not only as support in the structuring or purchase of the issue but also with credit enhancement products, provision of guarantees, and risk management such as exchange rate and political risks to increase the interest of investors. Likewise, the countries of the region must commit to updating their NDC’s. In general, they must take real measures beyond rhetoric that increase their ambition in sustainability, raise business and citizen awareness, and captivate responsible investors worldwide. To contribute to this purpose, sovereign and territorial entity green bonds are more than well-positioned.

Regarding research on the green bonds market in the region, although most of the information concerning issues was found, especially in public media such as their websites, a limitation of the study was the possibility of collecting the detailed elements for all transactions to achieve more rigorous quantitative analysis. Likewise, the investors do not publish detailed information on the location of the projects vs. headquarters. Added to this is the difficulty of not knowing the subsectors or type of asset invested, which therefore reduces the possibility of deepening. This allows for fundamental analysis in the issuer’s sector (which does not necessarily correspond to the destination of the projects), something with which the aforementioned GBTP platform can improve in the future with the help of the issuers and investors.

Finally, the accelerated growth of the green bonds and on a larger scale, of sustainable finance as well as the still-scarce related studies applied to the region confirm this as a recent field of study and support the potential for further research. There are compelling research possibilities regarding comparing with other emerging regions as well as interest rates and amortization schemes. This study could be expanded to social and sustainable bonds segments, characterizing specific sectors, and verifying relationships observed in other regions, all from various approaches and methods. Another possibility for future analysis arises from investigating the relationship between the offer of SFP and green bonds in emerging and developed markets and even the study of cases on the financial structuring of green issuances amid different types of issuers. Besides, the impact in the development of the green bond markets in light of the COVID-19 outbreak and concerns of climate change on both developed and developing economies should be on the agenda from an academic, political, and practitioner perspective. In the coming years, transition bonds, as a green bond subset, play a pivotal role in order to support a faster transition to low carbon economies, and thus, it allows to help brown companies become green. In this way, better market guidance, which could be provided by Climate Bonds Initiative and International Capital Market Association -ICMA-, to guide both issuers, investors, and markets are needed. The authors hope that, in the short term, the finance concept as a whole has to include, by default, sustainability; therefore, in this scenario, capital markets, financial mechanisms, companies, and customers play a pivotal role.