Recent Advances in Rice Varietal Development for Durable Resistance to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses through Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding

Abstract

1. Introduction

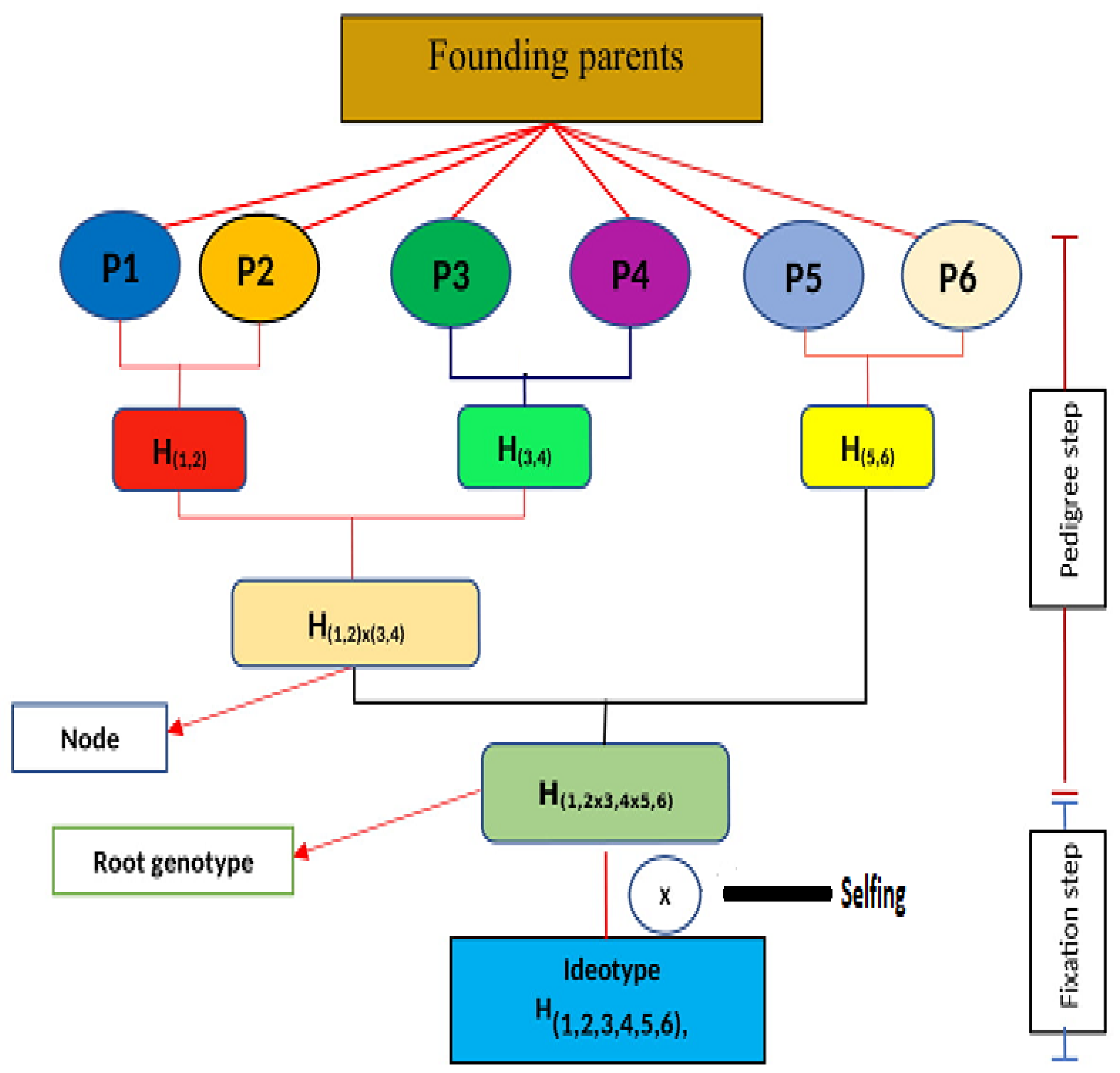

2. A Definite Gene Pyramiding Diagram

3. Gene Pyramiding Methods

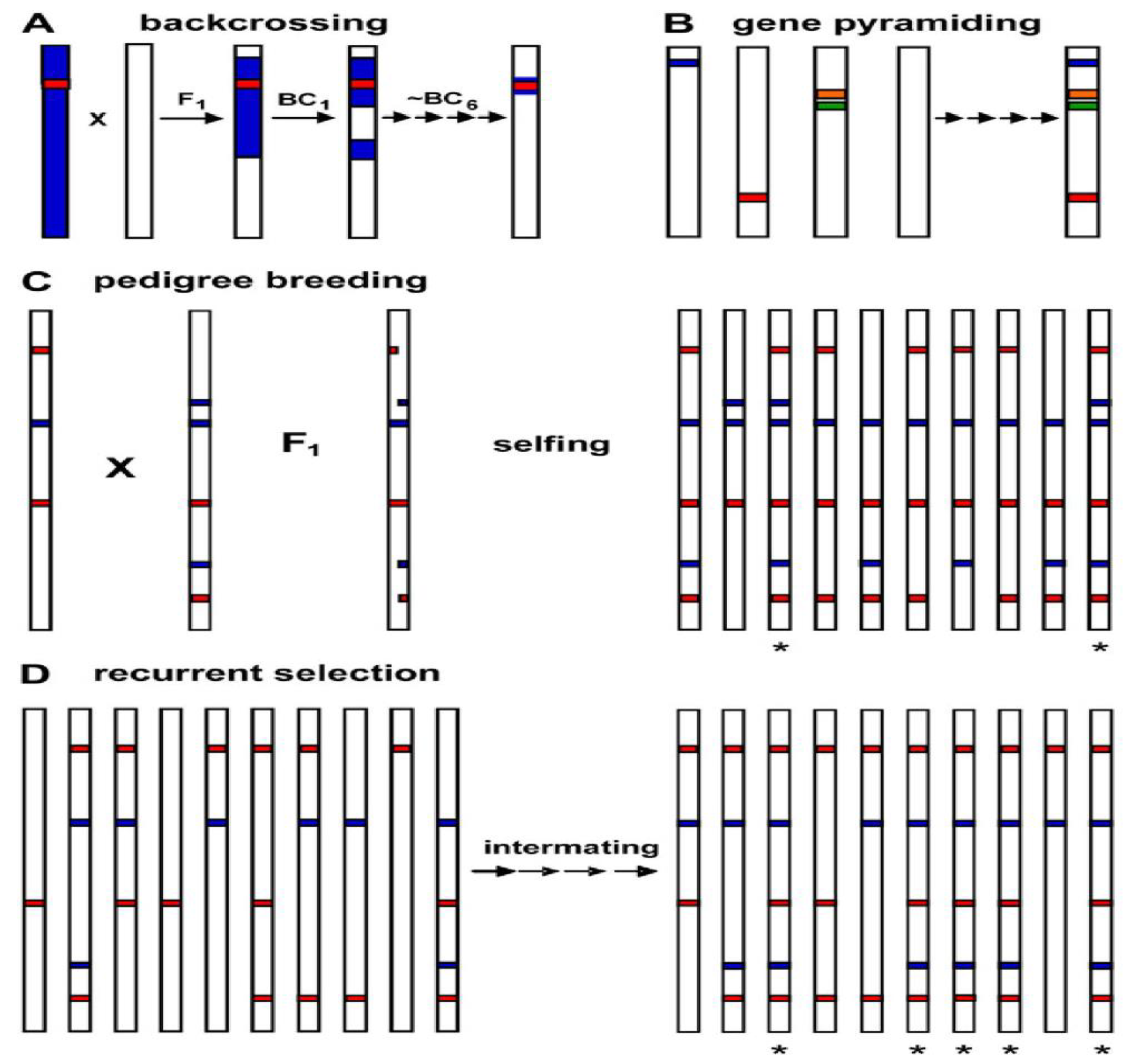

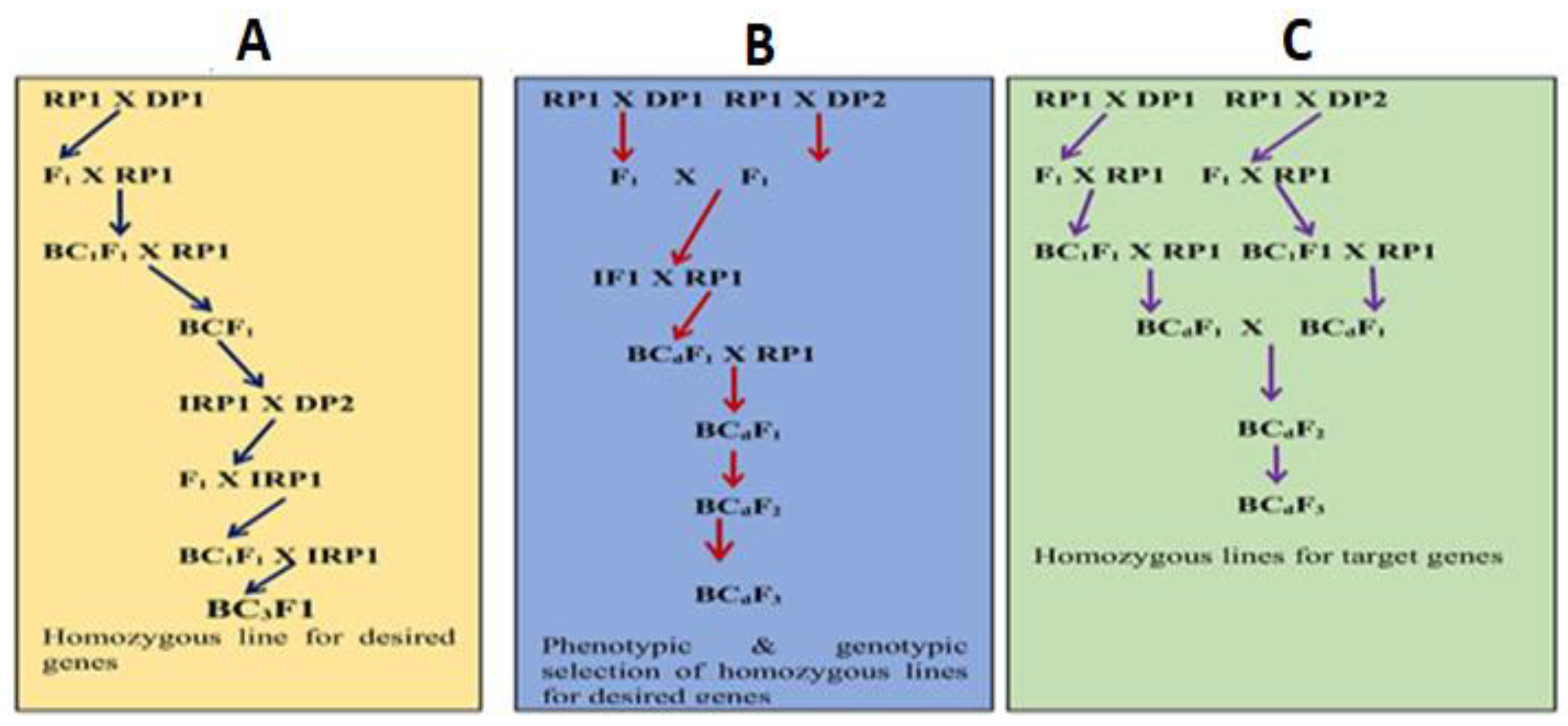

3.1. Gene Pyramiding through Conventional Backcrossing

3.2. Gene Pyramiding through Marker-Assisted Selection

3.3. Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding Techniques

4. Popularly Used Marker System in MAS-Based Gene Pyramiding in Rice

5. Efficiency of MAS-Based Gene Pyramiding in Rice

6. Advantages of Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding/Stacking

6.1. Speedy Recovery of Recurrent Genome Parent (RPG)

6.2. Solidity or Firmness

6.3. Minimization of Linkage Drag

6.4. Efficiency and Cost-Effectiveness

6.5. Availability of Markers and Molecular Techniques

6.6. Reduce Breeding Generations

6.7. Accuracy of Selection

7. Limitations of Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding

8. Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding for Abiotic and Biotic Stresses in Rice—Some True Success Stories

8.1. Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding for Blast Pathogens in Rice

8.2. Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding for Bacterial Blight Resistance in Rice

8.3. Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding for Rice Sheath Blight Resistance in Rice

8.4. Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding for Brown Planthopper Resistance in Rice

8.5. Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding for Drought Stress in Rice

8.6. Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding for Submergence Tolerance in Rice

8.7. Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding for Salt Tolerance Rice

8.8. Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding for Multiple Traits against Biotic and Abiotic Stresses in Rice

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bordey, F.H. The Impacts of Research on Philippine Rice Production. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Wright St. Urbana, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Leridon, H. Population. I. Popul. Societies 2020, 573, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Finatto, T.; de Oliveira, A.C.; Chaparro, C.; da Maia, L.C.; Farias, D.R.; Woyann, L.G.; Mistura, C.C.; Soares-Bresolin, A.P.; Llauro, C.; Panaud, O.; et al. Abiotic stress and genome dynamics: Specific genes and transposable elements response to iron excess in rice. Rice 2015, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramegowda, V.; Senthil-Kumar, M. The Interactive Effects of Simultaneous Biotic and Abiotic Stresses on Plants: Mechanistic Understanding from Drought and Pathogen Combination; Elsevier GmbH.: München, Germany, 2015; Volume 176, ISBN 9126735229. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, P.V.V.; Pisipati, S.R.; Momčilović, I.; Ristic, Z. Independent and Combined Effects of High Temperature and Drought Stress During Grain Filling on Plant Yield and Chloroplast EF-Tu Expression in Spring Wheat. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2011, 197, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasch, C.M.; Sonnewald, U. Simultaneous Application of Heat, Drought, and Virus to Arabidopsis Plants Reveals Significant Shifts in Signaling Networks. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1849–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatimah, F.; Prasetiyono, J.; Dadang, A.; Tasliah, T. Improvement of Early Maturity in Rice Variety BY Marker Assisted Backcross Breeding OF Hd2 Gene. Indones. J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 15, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.A.; Talbot, N.J.; Ebbole, D.J.; Farman, M.L.; Mitchell, T.K.; Orbach, M.J.; Thon, M.; Kulkarni, R.; Xu, J.-R.; Pan, H.; et al. The genome sequence of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Nature 2005, 434, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, N.J.; Lilley, C.J.; Urwin, P.E. Identification of genes involved in the response of arabidopsis to simultaneous biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 2028–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, P.; Ramegowda, V.; Senthil-Kumar, M. Shared and unique responses of plants to multiple individual stresses and stress combinations: Physiological and molecular mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziska, L.H.; Tomecek, M.B.; Gealy, D.R. Competitive Interactions between Cultivated and Red Rice as a Function of Recent and Projected Increases in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. Agron. J. 2010, 102, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, R.; Fahad, S.; Masood, N.; Rasool, A.; Ijaz, M.; Zahid, M.; Ihsan, M.Z.; Maqbool, M.M.; Ahmad, S.; Hussain, S.; et al. Rice Responses and Tolerance to Metal/Metalloid Toxicity; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2018; ISBN 9780128053744. [Google Scholar]

- Anami, B.S.; Malvade, N.N.; Palaiah, S. Classification of yield affecting biotic and abiotic paddy crop stresses using field images. Inf. Process. Agric. 2020, 7, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, S.M.; Scherm, H.; Chakraborty, S. Climate Change and Plant Disease Management. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1999, 37, 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanksley, S.D.; Young, N.D.; Paterson, A.H.; Bonierbale, M.W. RFLP mapping in piant breeding: New tools for an old science. Bio/Technology 1989, 7, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, N.D.; Tanksley, S.D. Restriction fragment length polymorphism maps and the concept of graphical genotypes. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1989, 77, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mew, T.W. Changes in Race Frequency of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in Response to Rice Cultivars Planted in the Philippines. Plant Dis. 1992, 76, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M.L.C.; Bustamam, M.; Cruz, W.T.; Leach, J.E.; Nelson, R.J. Movement of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in Southeast Asia Detected Using PCR-Based DNA Fingerprinting. Phytopathology 1997, 87, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Singh, A.; Singh, V.K.; Gopala, K.S.; Ellur, R.K.; Singh, D.; Ravindran, G.; Bhowmick, P.K.; Nagarajan, M.; Vinod, K.K.; et al. Public private partnership for hybrid rice. In Proceedings of the 6th International Hybrid Rice Symposium, Hyderabad, India, 10–12 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dokku, P.; Das, K.M.; Rao, G.J.N. Pyramiding of four resistance genes of bacterial blight in Tapaswini, an elite rice cultivar, through marker-assisted selection. Euphytica 2013, 192, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokku, P.; Das, K.M.; Rao, G.J.N. Genetic enhancement of host plant-resistance of the Lalat cultivar of rice against bacterial blight employing marker-assisted selection. Biotechnol. Lett. 2013, 35, 1339–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, I.A.; Singh, D. The future for rust resistant wheat in Australia. J. Aust. Inst. Agric. Sci. 1952, 18, 190–197. [Google Scholar]

- Das, G.; Rao, G.J.N.; Varier, M.; Prakash, A.; Prasad, D. Improved Tapaswini having four BB resistance genes pyramided with six genes/QTLs, resistance/tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses in rice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, G.; Rao, G.J.N. Molecular marker assisted gene stacking for biotic and abiotic stress resistance genes in an elite rice cultivar. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Z.; Shi, J.; Zeng, Y.; Qian, Q.; Yang, C. Application of a simplified marker-assisted backcross technique for hybrid breeding in rice. Biology 2014, 69, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, G.; Rafii, M.Y.; Ismail, M.R.; Puteh, A.B.; Rahim, H.A.; Islam, N.K.; Latif, M.A. A review of microsatellite markers and their applications in rice breeding programs to improve blast disease resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 22499–22528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Servin, B.; Martin, O.C.; Mézard, M.; Hospital, F. Toward a theory of marker-assisted gene pyramiding. Genetics 2004, 168, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, S.K.; Nayak, D.K.; Mohanty, S.; Behera, L.; Barik, S.R. Pyramiding of three bacterial blight resistance genes for broad-spectrum resistance in deepwater rice variety, Jalmagna. Rice 2015, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinta, W.; Toojinda, T.; Thummabenjapone, P.; Sanitchon, J. Pyramiding of blast and bacterial leaf blight resistance genes into rice cultivar RD6 using marker assisted selection. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 12, 4432–4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpurohit, D.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, M.; Paul, P.; Awasthi, A.; Osman Basha, P.; Puri, A.; Jhang, T.; Singh, K.; Dhaliwal, H.S. Pyramiding of two bacterial blight resistance and a semidwarfing gene in Type 3 Basmati using marker-assisted selection. Euphytica 2011, 178, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospital, F. Selection in backcross programmes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2005, 360, 1503–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Valdés, M.H. A Model for Marker-Based Selection in Gene Introgression Breeding Programs. Crop Sci. 2000, 40, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumlop, S.; Finckh, M.R. Applications and Potentials of Marker Assisted Selection (MAS) in Plant Breeding; Bundesamt für Naturschutz (German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation): Bonn, Germany, 2011; ISBN 9783896240330. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M.M.; Rafii, M.Y.; Ismail, M.R.; Mahmood, M.; Rahim, H.A.; Alam, M.A.; Ashkani, S.; Malek, M.A.; Latif, M.A. Marker-assisted backcrossing: A useful method for rice improvement. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2015, 29, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lema, M. Marker Assisted Selection in Comparison to Conventional Plant Breeding: Review Article. Agric. Res. Technol. Open Access J. 2018, 14, 555914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S.; Malathi, D. Gene Pyramiding For Biotic Stress Tolerance In Crop Plants. Wkly. Sci. Res. J. 2013, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, S.; Anuradha, G.; Kumar, R.R.; Vemireddy, L.R.; Sudhakar, R.; Donempudi, K.; Venkata, D.; Jabeen, F.; Narasimhan, Y.K.; Marathi, B.; et al. Identification of QTLs and possible candidate genes conferring sheath blight resistance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Springerplus 2015, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.; Ahmad, J. In vitro wheat haploid embryo production by wheat x maize cross system under different environmental conditions. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 48, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Chukwu, S.C.; Rafii, M.Y.; Ramlee, S.I.; Ismail, S.I.; Hasan, M.M.; Oladosu, Y.A.; Magaji, U.G.; Akos, I.; Olalekan, K.K. Bacterial leaf blight resistance in rice: A review of conventional breeding to molecular approach. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 1519–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moose, S.P.; Mumm, R.H. Molecular plant breeding as the foundation for 21st century crop improvement. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Joshi, R.; Nayak, S. Gene pyramiding-A broad spectrum technique for developing durable stress resistance in crops. Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010, 5, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, K.; Choudhary, K.; Choudhary, O.P.; Shekhawat, N.S. Marker Assisted Selection: A Novel Approach for Crop Improvement. J. Agron. 2008, 1, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, K.; Hashimoto, N.; Daigen, M.; Ashikawa, I. Development of PCR-based SNP markers for rice blast resistance genes at the Piz locus. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 108, 1212–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, M.J. High-Throughput SNP Genotyping to Accelerate Crop Improvement. Plant Breed. Biotechnol. 2014, 2, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semagn, K.; Babu, R.; Hearne, S.; Olsen, M. Single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping using Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR (KASP): Overview of the technology and its application in crop improvement. Mol. Breed. 2014, 33, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, K.A.; Quinton-Tulloch, M.J.; Amgai, R.B.; Dhakal, R.; Khatiwada, S.P.; Vyas, D.; Heine, M.; Witcombe, J.R. Accelerating public sector rice breeding with high-density KASP markers derived from whole genome sequencing of indica rice. Mol. Breed. 2018, 38, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, K.-S.; Jeong, Y.-M.; Oh, H.; Oh, J.; Kang, D.-Y.; Kim, N.; Lee, E.; Baek, J.; Kim, S.L.; Choi, I.; et al. Development of 454 New Kompetitive Allele-Specific PCR (KASP) Markers for Temperate japonica Rice Varieties. Plants 2020, 9, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheon, K.-S.; Jeong, Y.-M.; Lee, Y.-Y.; Oh, J.; Kang, D.-Y.; Oh, H.; Kim, S.L.; Kim, N.; Lee, E.; Baek, J.; et al. Kompetitive Allele-Specific PCR Marker Development and Quantitative Trait Locus Mapping for Bakanae Disease Resistance in Korean Japonica Rice Varieties. Plant Breed. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.K.; Nayak, D.K.; Pandit, E.; Behera, L.; Anandan, A.; Mukherjee, A.K.; Lenka, S.; Barik, D.P. Incorporation of Bacterial Blight Resistance Genes Into Lowland Rice Cultivar Through Marker-Assisted Backcross Breeding. Phytopathology 2016, 106, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreher, K.; Morris, M.; Khairallah, M.; Ribaut, J.M.; Shivaji, P.; Ganesan, S. Is marker-assisted selection cost-effective compared with conventional plant breeding methods? The case of quality protein Maize. Econ. Soc. Issues Agric. Biotechnol. 2002, 203–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Angeles, E.R.; Domingo, J.; Magpantay, G.; Singh, S.; Zhang, G.; Kumaravadivel, N.; Bennett, J.; Khush, G.S. Pyramiding of bacterial blight resistance genes in rice: Marker-assisted selection using RFLP and PCR. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1997, 95, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.R.; Rai, A.K.; Gupta, S.K.; Vijayan, J.; Devanna, B.N.; Ray, S. Rice Blast Management Through Host-Plant Resistance: Retrospect and Prospects. Agric. Res. 2012, 1, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xiao, N.; Chen, Y.; Yu, L.; Pan, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, N.; Ji, H.; Dai, Z.; et al. Comprehensive evaluation of resistance effects of pyramiding lines with different broad-spectrum resistance genes against Magnaporthe oryzae in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Rice 2019, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hospital, F.; Charcosset, A. Marker-assisted introgression of quantitative trait loci. Genetics 1997, 147, 1469–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.; Bohn, M.; Melchinger, A.E. Minimum Sample Size and Optimal Positioning of. Design 1999, 975, 967–975. [Google Scholar]

- Visscher, P.M.; Haley, C.S.; Thompson, R. Marker-assisted introgression in backcross breeding programs. Genetics 1996, 144, 1923–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Sidhu, J.S.; Huang, N.; Vikal, Y.; Li, Z.; Brar, D.S.; Dhaliwal, H.S.; Khush, G.S. Molecular progress on the mapping and cloning of functional genes for blast disease in rice (Oryza sativa L.): Current status and future considerations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2001, 102, 1011–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwu, S.C.; Rafii, M.Y.; Ramlee, S.I.; Ismail, S.I.; Oladosu, Y.; Muhammad, I.; Musa, I.; Ahmed, M.; Jatto, M.I.; Yusuf, B.R. Recovery of recurrent parent genome in a marker-assisted backcrossing against rice blast and blight infections using functional markers and SSRs. Plants 2020, 9, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S.; Yang, J.-Y.; Yu, J.-K.; Lee, Y.; Park, Y.-J.; Kang, K.-K.; Cho, Y.-G. Breeding of High Cooking and Eating Quality in Rice by Marker-Assisted Backcrossing (MABc) Using KASP Markers. Plants 2021, 10, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-W.; Shin, D.; Cho, J.-H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kwon, Y.; Park, D.-S.; Ko, J.-M.; Lee, J.-H. Accelerated development of rice stripe virus-resistant, near-isogenic rice lines through marker-assisted backcrossing. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, S.; Bhat, M.A.; Bhat, K.A.; Chalkoo, S.; Mir, M.R. Marker assisted selection in rice. J. Phytol. 2010, 2, 66–81. [Google Scholar]

- Collard, B.C.Y.; Mackill, D.J. Marker-assisted selection: An approach for precision plant breeding in the twenty-first century. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospital, F. Size of donor chromosome segments around introgressed loci and reduction of linkage drag in marker-assisted backcross programs. Genetics 2001, 158, 1363–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribaut, J.M.; de Vicente, M.C.; Delannay, X. Molecular breeding in developing countries: Challenges and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 13, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jena, K.K.; Mackill, D.J. Molecular markers and their use in marker-assisted selection in rice. Crop Sci. 2008, 48, 1266–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Singh, V.P.; Prabhu, K.V.; Mohapatra, T.; Singh, N.K.; Sharma, T.R.; Nagarajan, M.; Ellur, R.K.; Singh, A.; et al. Marker assisted selection: A paradigm shift in Basmati breeding. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2011, 71, 120. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Zhao, X.; Laroche, A.; Lu, Z.X.; Liu, H.K.; Li, Z. Genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS), An ultimate marker-assisted selection (MAS) tool to accelerate plant breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, G.; Patra, J.K.; Baek, K. Corrigendum: Insight into MAS: A molecular tool for development of stress resistant and quality of rice through gene stacking. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amagai, Y.; Watanabe, N.; Kuboyama, T. Genetic mapping and development of near-isogenic lines with genes conferring mutant phenotypes in Aegilops tauschii and synthetic hexaploid wheat. Euphytica 2015, 205, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearsey, M.J. The principles of QTL analysis (a minimal mathematics approach). J. Exp. Bot. 1998, 49, 1619–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchinger, A.E.; Friedrich Utz, H.; Schör, C.C. Quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping using different testers and independent population samples in maize reveals low power of QTL detection and large bias in estimates of QTL effects. Genetics 1998, 149, 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Z.H.; Fortune, J.A.; Gallagher, J. Anatomical structure and nutritive value of lupin seed coats. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2001, 52, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwu, S.C.; Rafii, M.Y.; Ramlee, S.I.; Ismail, S.I.; Oladosu, Y.; Okporie, E.; Onyishi, G.; Utobo, E.; Ekwu, L.; Swaray, S.; et al. Marker-assisted selection and gene pyramiding for resistance to bacterial leaf blight disease of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2019, 33, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkani, S.; Rafii, M.Y.; Rahim, H.A.; Latif, M.A. Genetic dissection of rice blast resistance by QTL mapping approach using an F3 population. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 40, 2503–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrão, S.; Cecília Almadanim, M.; Pires, I.S.; Abreu, I.A.; Maroco, J.; Courtois, B.; Gregorio, G.B.; McNally, K.L.; Margarida Oliveira, M. New allelic variants found in key rice salt-tolerance genes: An association study. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2013, 11, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-C.; Chiu, C.-H.; Yap, R.; Tseng, Y.-C.; Wu, Y.-P. Pyramiding Bacterial Blight Resistance Genes in Tainung82 for Broad-Spectrum Resistance Using Marker-Assisted Selection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Hu, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Gao, G.; Zhang, Q.; Xiao, J.; He, Y. Evaluation and breeding application of six brown planthopper resistance genes in rice maintainer line Jin 23B. Rice 2018, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N. Fine mapping and DNA marker-assisted pyramiding of the three major genes for blast resistance in rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000, 100, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Feng, Y.; Bao, L. Improving blast resistance of Jin 23B and its hybrid rice by marker-assisted gene pyramiding. Mol. Breed. 2012, 30, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikas, S.H.B.; Atul, K.S.; Ashutosh, S. Marker-assisted improvement of bacterial blight resistance in parental lines of Pusa RH10, a superfine grain aromatic rice hybrid. Mol. Breed. 2010, 26, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, S.; Verulkar, S.; Chandel, G.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, B.; Bennett, J. Genetic analysis and pyramiding of two gall midge resistance genes (Gm-2 and Gm-6t) in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Euphytica 2001, 122, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Dai, H.; He, J.; Kang, H.; Pan, G.; Huang, J.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, Q.; et al. Marker assisted pyramiding of two brown planthopper resistance genes, Bph3 and Bph27 (t), into elite rice Cultivars. Rice 2016, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patroti, P.; Vishalakshi, B.; Umakanth, B.; Suresh, J.; Senguttuvel, P.; Madhav, M.S. Marker-assisted pyramiding of major blast resistance genes in Swarna-Sub1, an elite rice variety (Oryza sativa L.). Euphytica 2019, 215, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K.; Singh, R.P.; Singh, P. Identification of good combiners in early maturing × high yielding cultivars of Indica rice (Oryza sativa L.). Bangladesh J. Bot. 2013, 42, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.; Jeung, J.; Noh, T.; Cho, Y.; Park, S.; Park, H.; Shin, M.; Kim, C.; Jena, K.K. Development of breeding lines with three pyramided resistance genes that confer broad-spectrum bacterial blight resistance and their molecular analysis in rice. Rice 2013, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd, N.; Shamsudin, A.; Swamy, B.P.M.; Ratnam, W.; Teressa, M.; Cruz, S.; Raman, A.; Kumar, A. Marker assisted pyramiding of drought yield QTLs into a popular Malaysian rice. BMC Genet. 2016, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandian, B.A.; Joel, J.; Nachimuthu, V.V. Marker-aided selection and validation of various Pi gene combinations for rice blast resistance in elite rice variety ADT 43. J. Genet. 2018, 97, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Y.; Chen, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Xu, J.; Ali, J.; Li, Z.; Roy, S.J. Simultaneous Improvement and Genetic Dissection of Salt Tolerance of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) by Designed QTL Pyramiding. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Yang, Q.; Huang, M.; Guo, T.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, G.; Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Zhu, X.; et al. Improvement of rice blast resistance by developing monogenic lines, two-gene pyramids and three-gene pyramid through MAS. Rice 2019, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, J.; Lei, Y.; Kim, S. An effective strategy for fertility improvement of indica-japonica hybrid rice by pyramiding S5-n, f5-n, and pf12-j. Mol. Breed. 2019, 39, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinada, H.; Iwata, N.; Sato, T.; Fujino, K. QTL pyramiding for improving of cold tolerance at fertilization stage in rice. Breed. Sci. 2014, 488, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yang, T.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Q.; Huang, Z.; Mao, X.; Dong, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, G.; Liu, B. Identification and pyramiding of QTLs for cold tolerance at the bud bursting and the seedling stages by use of single segment substitution lines in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Mol. Breed. 2016, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, J.; Raveendra, C.; Savitha, P.; Vidya, V.; Chaithra, T.L.; Velprabakaran, S.; Saraswathi, R.; Ramanathan, A.; Arumugam Pillai, M.P.; Arumugachamy, S.; et al. Gene Pyramiding for Achieving Enhanced Resistance to Bacterial Blight, Blast, and Sheath Blight Diseases in Rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwu, S.C.; Rafii, M.Y.; Ramlee, S.I.; Ismail, S.I.; Oladosu, Y.; Kolapo, K.; Musa, I.; Halidu, J.; Muhammad, I.; Ahmed, M. Marker-Assisted Introgression of Multiple Resistance Genes Confers Broad Spectrum Resistance against Bacterial Leaf Blight and Blast Diseases in PUTRA-1 Rice Variety. Agronomy 2019, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Singh, U.M.; Singh, A.K.; Alam, S.; Venkateshwarlu, C.; Nachimuthu, V.V.; Yadav, S.; Abbai, R.; Selvaraj, R.; Devi, M.N.; et al. Marker Assisted Forward Breeding to Combine Multiple Biotic-Abiotic Stress Resistance/Tolerance in Rice. Rice 2020, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaloddin, M.; Durga Rani, C.V.; Swathi, G.; Anuradha, C.; Vanisri, S.; Rajan, C.P.D.; Krishnam Raju, S.; Bhuvaneshwari, V.; Jagadeeswar, R.; Laha, G.S.; et al. Marker Assisted Gene Pyramiding (MAGP) for bacterial blight and blast resistance into mega rice variety “Tellahamsa”. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swathi, G.; Rani, C.V.D.; Madhav, M.S.; Vanisree, S. Marker-assisted introgression of the major bacterial blight resistance genes, Xa21 and xa13, and blast resistance gene, Pi54, into the popular rice variety, JGL1798. Mol. Breed. 2019, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.A.; Balachiranjeevi, C.H.; Naik, S.B.; Rekha, G.; Rambabu, R. Marker-assisted pyramiding of bacterial blight and gall midge resistance genes into RPHR-1005, the restorer line of the popular rice hybrid DRRH-3. Mol. Breed. 2017, 37, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septiningsih, E.M.; Pamplona, A.M.; Sanchez, D.L.; Neeraja, C.N.; Vergara, G.V.; Heuer, S.; Ismail, A.M.; Mackill, D.J. Development of submergence-tolerant rice cultivars: The Sub1 locus and beyond. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhu, X.; Shen, Y.; He, Z. Genetic characterization and fine mapping of the blast resistance locus Pigm(t) tightly linked to Pi2 and Pi9 in a broad-spectrum resistant Chinese variety. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006, 113, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biradar, S.K.; Sundaram, R.M.; Thirumurugan, T.; Bentur, J.S.; Amudhan, S.; Shenoy, V.V.; Mishra, B.; Bennett, J.; Sarma, N.P. Identification of flanking SSR markers for a major rice gall midge resistance gene Gm1 and their validation. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 109, 1468–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himabindu, K.; Suneetha, K.; Sama, V.S.A.K.; Bentur, J.S. A new rice gall midge resistance gene in the breeding line CR57-MR1523, mapping with flanking markers and development of NILs. Euphytica 2010, 174, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Mackill, D.J. A major locus for submergence tolerance mapped on rice chromosome 9. Mol. Breed. 1996, 2, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.; Subudhi, P.K.; Senadhira, D.; Manigbas, N.L.; Sen-Mandi, S.; Huang, N. Mapping QTLs for submergence tolerance in rice by AFLP analysis and selective genotyping. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1997, 255, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Xu, X.; Ronald, P.C.; Mackill, D.J. A high-resolution linkage map of the vicinity of the rice submergence tolerance locus Sub1. Mol. Gen Genet 2000, 263, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Ma, T.; Zhang, A.; Ong, K.H.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.; Yin, Z. Marker-assisted breeding of the rice restorer line Wanhui 6725 for disease resistance, submergence tolerance and aromatic fragrance. Rice 2016, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Sangha, J.S. Marker-assisted breeding of Xa4, Xa21 and Xa27 in the restorer lines of hybrid rice for broad-spectrum and enhanced disease resistance to bacterial blight. Mol. Breed. 2012, 30, 1601–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruengphayak, S.; Chaichumpoo, E.; Phromphan, S.; Kamolsukyunyong, W.; Sukhaket, W.; Phuvanartnarubal, E.; Korinsak, S.; Korinsak, S.; Vanavichit, A. Pseudo-backcrossing design for rapidly pyramiding multiple traits into a preferential rice variety. Rice 2015, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, C.; Hao, W.; Ya-dong, Z.; Zhen, Z.; Qi-yong, Z.; Li-hui, Z.; Shu, Y.; Ling, Z.; Xin, Y.; Chun-fang, Z.; et al. ScienceDirect Genetic Improvement of Japonica Rice Variety Wuyujing 3 for Stripe Disease Resistance and Eating Quality by Pyramiding Stv-b i and Wx-mq. Rice Sci. 2016, 23, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinke, R.; Man, S.; Kim, B.K. Developing japonica rice introgression lines with multiple resistance genes for brown planthopper, bacterial blight, rice blast, and rice stripe virus using molecular breeding. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2018, 293, 1565–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Ma, T.; Zhang, A. Marker-assisted breeding of Chinese elite rice cultivar 9311 for disease resistance to rice blast and bacterial blight and tolerance to submergence. Mol. Breed. 2017, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Lu, G.; Zeng, L.; Wang, G.-L. Two broad-spectrum blast resistance genes, Pi9(t) and Pi2(t), are physically linked on rice chromosome 6. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2002, 267, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, J.-P.; Noh, T.-H.; Kim, K.-Y.; Kim, J.-J.; Kim, Y.-G.; Jena, K.K. Expression levels of three bacterial blight resistance genes against K3a race of Korea by molecular and phenotype analysis in japonica rice (O. sativa L.). J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2009, 12, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeung, J.U.; Kim, B.R.; Cho, Y.C.; Han, S.S.; Moon, H.P.; Lee, Y.T.; Jena, K.K. A novel gene, Pi40(t), linked to the DNA markers derived from NBS-LRR motifs confers broad spectrum of blast resistance in rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2007, 115, 1163–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, J.; Cho, Y.; Won, Y.; Ahn, E.; Baek, M.; Kim, M.; Kim, B.; Jena, K.K. Development of Resistant Gene-Pyramided Japonica Rice for Multiple Biotic Stresses Using Molecular Marker-Assisted Selection. Plant Breed. Biotech. 2015, 2015, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nas, T.M.S.; Sanchez, D.L.; Diaz, M.G.Q.; Mendioro, M.S.; Virmani, S.S. Pyramiding of thermosensitive genetic male sterility (TGMS) genes and identification of a candidate tms5 gene in rice. Euphytica 2005, 145, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.K. Pyramiding transgenes for multiple resistance in rice against bacterial blight, yellow stem borer and sheath blight. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2002, 106, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J. Pyramiding of two BPH resistance genes and Stv-b i gene using. Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 2013, 13, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Yang, D.; Ali, J.; Mou, T. Molecular marker-assisted pyramiding of broad-spectrum disease resistance genes, Pi2 and Xa23, into GZ63-4S, an elite thermo-sensitive genic male-sterile line in rice. Mol. Breed. 2015, 35, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korinsak, S.; Siangliw, M.; Kotcharerk, J.; Jairin, J.; Toojinda, T. Field Crops Research Improvement of the submergence tolerance and the brown planthopper resistance of the Thai jasmine rice cultivar KDML105 by pyramiding Sub1 and Qbph12. F. Crop. Res. 2016, 188, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivong, P.; Korinsak, S.; Korinsak, S.; Siangliw, J.L.; Vanavichit, A.; Toojinda, T. Marker-assisted selection to improve submergence tolerance, blast resistance and strong fragrance in glutinous rice. Genom. Genet. 2014, 2014, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, Y.; Cho, J.; Park, H.; Noh, T.; Park, D.; Lee, J.Y.; Sohn, Y.; Shin, D.; Song, Y.C.; Kwon, Y.; et al. Pyramiding of two rice bacterial blight resistance genes, Xa3 and Xa4, and a closely linked cold-tolerance QTL on chromosome. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2016, 129, 1861–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.; Castilla, N.; Hadi, B.; Tanaka, T.; Chiba, S.; Sato, I. Rice blast management in Cambodian rice fields using Trichoderma harzianum and a resistant variety. Crop Prot. 2020, 135, 104864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babujee, L.; Gnanamanickam, S.S. Molecular tools for characterization of rice blast pathogen (Magnaporthe grisea) population and molecular marker-assisted breeding for disease resistance. Curr. Sci. 2000, 78, 248–257. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkani, S.; Yusop, M.R.; Shabanimofrad, M.; Azadi, A.; Ali Ghasemzadeh, P.A.; Mohammad, A.L. Allele Mining Strategies: Principles and Utilisation for Blast Resistance Genes in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2015, 17, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Mitchell, T.; Hu, Y.; Liu, X.; Dai, L.; Wang, G.-L. Recent progress and understanding of the molecular mechanisms of the rice- Magnaporthe oryzae interaction. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2010, 11, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesari, S.; Thilliez, G.; Ribot, C.; Chalvon, V.; Michel, C.; Jauneau, A.; Rivas, S.; Alaux, L.; Kanzaki, H.; Okuyama, Y.; et al. The Rice Resistance Protein Pair RGA4/RGA5 Recognizes the Magnaporthe oryzae Effectors AVR-Pia and AVR1-CO39 by Direct Binding. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 1463–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, Y.; Kanzaki, H.; Abe, A.; Yoshida, K.; Tamiru, M.; Saitoh, H.; Fujibe, T.; Matsumura, H.; Shenton, M.; Galam, D.C.; et al. A multifaceted genomics approach allows the isolation of the rice Pia-blast resistance gene consisting of two adjacent NBS-LRR protein genes. Plant J. 2011, 66, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, A.K.; Kumar, S.P.; Gupta, S.K.; Gautam, N.; Singh, N.K.; Sharma, T.R. Functional complementation of rice blast resistance gene Pi-k h (Pi54) conferring resistance to diverse strains of Magnaporthe oryzae. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2011, 20, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Wu, J.; Chen, C.; Wu, W.; He, X.; Lin, F.; Wang, L.; Ashikawa, I.; Matsumoto, T.; Wang, L.; et al. The isolation of Pi1, an allele at the Pik locus which confers broad spectrum resistance to rice blast. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 125, 1047–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Yasuda, N.; Fujita, Y.; Koizumi, S.; Yoshida, H. Identification of the blast resistance gene Pit in rice cultivars using functional markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010, 121, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Huang, L.; Feng, G.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Jiang, N.; Yan, W.; Xu, L.; Sun, P.; et al. Molecular mapping of the new blast resistance genes Pi47 and Pi48 in the durably resistant local rice cultivar Xiangzi 3150. Phytopathology 2011, 101, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Soubam, D.; Singh, P.K.; Thakur, S.; Singh, N.K.; Sharma, T.R. A novel blast resistance gene, Pi54rh cloned from wild species of rice, Oryza rhizomatis confers broad spectrum resistance to Magnaporthe oryzae. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2012, 12, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.X.; Liang, L.Q.; He, X.Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.S.; Liu, W.; Liu, X.Q.; Lin, F. Development of a marker specific for the rice blast resistance gene Pi39 in the Chinese cultivar Q15 and its use in genetic improvement. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2015, 29, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhu, X.; Yang, J.; Bordeos, A.; Wang, G.; Leach, J.E.; Leung, H. Fine-mapping and molecular marker development for Pi56(t), a NBS-LRR gene conferring broad-spectrum resistance to Magnaporthe oryzae in rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2013, 126, 985–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, N.; Inoue, H.; Kato, T.; Funao, T.; Shirota, M.; Shimizu, T.; Kanamori, H.; Yamane, H.; Hayano-Saito, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; et al. Durable panicle blast-resistance gene Pb1 encodes an atypical CC-NBS-LRR protein and was generated by acquiring a promoter through local genome duplication. Plant J. 2010, 64, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuoka, S.; Saka, N.; Koga, H.; Ono, K.; Shimizu, T.; Ebana, K.; Hayashi, N.; Takahashi, A.; Hirochika, H.; Okuno, K.; et al. Loss of Function of a Proline-Containing Protein Confers Durable Disease Resistance in Rice. Science 2009, 325, 998–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, S.; Rehman, A.; Shahzad, B.; Tanveer, M.; Saud, S.; Kamran, M.; Ihtisham, M.; Khan, S.U.; Turan, V.; ur Rahman, M.H. Rice Responses and Tolerance to Metal/Metalloid Toxicity. In Advances in Rice Research for Abiotic Stress Tolerance; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Shang, J.; Chen, D.; Lei, C.; Zou, Y.; Zhai, W.; Liu, G.; Xu, J.; Ling, Z.; Cao, G.; et al. A B-lectin receptor kinase gene conferring rice blast resistance. Plant J. 2006, 46, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Xiao, N.; Yu, L.; Pan, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G.; Dai, Z.; Pan, X.; Li, A. Combination Patterns of Major R Genes Determine the Level of Resistance to the M. oryzae in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuoka, S.; Saka, N.; Mizukami, Y.; Koga, H.; Yamanouchi, U.; Yoshioka, Y.; Hayashi, N.; Ebana, K.; Mizobuchi, R.; Yano, M. Gene pyramiding enhances durable blast disease resistance in rice. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 7773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Luo, L.; Wang, H.; Guo, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Q.; Chen, Z. Pyramiding of Pi46 and Pita to improve blast resistance and to evaluate the resistance effect of the two R genes. J. Integr. Agric. 2016, 15, 2290–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khush, G.S.; Mackill, D.J.; Sidhu, G.S. Breeding Rice for Resistance to Bacterial Blight; Int. Rice Res. Inst.: Los Baños, Philipines, 1989; Volume 16, ISBN 971104188X. [Google Scholar]

- Bhasin, H.; Bhatia, D.; Raghuvanshi, S.; Lore, J.S.; Sahi, G.K.; Kaur, B.; Vikal, Y.; Singh, K. New PCR-based sequence-tagged site marker for bacterial blight resistance gene Xa38 of rice. Mol. Breed. 2012, 30, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, W.; Yu, C.; Cheng, C.; Cheng, Y.; Yan, C.; Chen, J. Quantitative trait loci mapping for bacterial blight resistance in rice using bulked segregant analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 11847–11861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, D.; Wang, J.; Zeng, X.; Gu, K.; Qiu, C.; Yang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Goh, M.; Luo, Y.; Murata-Hori, M.; et al. The Rice TAL effector-dependent resistance protein XA10 triggers cell death and calcium depletion in the endoplasmic reticulum. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskar Rao, T.; Chopperla, R.; Prathi, N.B.; Balakrishnan, M.; Prakasam, V.; Laha, G.S.; Balachandran, S.M.; Mangrauthia, S.K. A Comprehensive Gene Expression Profile of Pectin Degradation Enzymes Reveals the Molecular Events during Cell Wall Degradation and Pathogenesis of Rice Sheath Blight Pathogen Rhizoctonia solani AG1-IA. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Mazumdar, P.; Harikrishna, J.A.; Babu, S. Sheath blight of rice: A review and identification of priorities for future research. Planta 2019, 250, 1387–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savary, S.; Willocquet, L.; Teng, P.S. Modelling sheath blight epidemics on rice tillers. Agric. Syst. 1997, 55, 359–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channamallikarjuna, V.; Sonah, H.; Prasad, M.; Rao, G.J.N.; Chand, S.; Upreti, H.C.; Singh, N.K.; Sharma, T.R. Identification of major quantitative trait loci qSBR11-1 for sheath blight resistance in rice. Mol. Breed. 2010, 25, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, K.A.; Karmakar, S.; Molla, J.; Bajaj, P.; Varshney, R.K.; Datta, S.K.; Datta, K. Understanding sheath blight resistance in rice: The road behind and the road ahead. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Pinson, S.R.M.; Fjellstrom, R.G.; Tabien, R.E. Phenotypic gain from introgression of two QTL, qSB9-2 and qSB12-1, for rice sheath blight resistance. Mol. Breed. 2012, 30, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Singh, Y.; Xalaxo, S.; Verulkar, S.; Yadav, N.; Singh, S.; Singh, N.; Prasad, K.S.N.; Kondayya, K.; Rao, P.V.R.; et al. From QTL to variety-harnessing the benefits of QTLs for drought, flood and salt tolerance in mega rice varieties of India through a multi-institutional network. Plant Sci. 2016, 242, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, S.; Yuan, M. An update on molecular mechanism of disease resistance genes and their application for genetic improvement of rice. Mol. Breed. 2019, 39, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Singh, V.K.; Singh, A.; Ellur, R.K.; Pandian, R.T.P.; Gopala Krishnan, S.; Singh, U.D.; Nagarajan, M.; Vinod, K.K.; Prabhu, K.V. Introgression of multiple disease resistance into a maintainer of Basmati rice CMS line by marker assisted backcross breeding. Euphytica 2015, 203, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, S.; Wei, S.; Sun, W. Strategies to Manage Rice Sheath Blight: Lessons from Interactions between Rice and Rhizoctonia solani. Rice 2021, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, W.; Feng, M.; Pan, X. Improvement of Rice Resistance to Sheath Blight by Pyramiding QTLs Conditioning Disease Resistance and Tiller Angle. Rice Sci. 2014, 21, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Lu, F.; Zhai, B.P.; Lu, M.H.; Liu, W.C.; Zhu, F.; Wu, X.W.; Chen, G.H.; Zhang, X.X. Outbreaks of the brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens (Stål) in the yangtze river delta: Immigration or local reproduction? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, M.J.; Heong, K.L. The role of biodiversity in the dynamics and management of insect pests of tropical irrigated rice—A review. Bull. Entomol. Res. 1994, 84, 567–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Zhang, W.; Liu, B.; Hu, J.; Wei, Z.; Shi, Z.; He, R.; Zhu, L.; Chen, R.; Han, B.; et al. Identification and characterization of Bph14, a gene conferring resistance to brown planthopper in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 22163–22168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Liu, H.; Zeng, Y.; Du, B.; Zhu, L.; He, G.; Chen, R. Marker assisted pyramiding of Bph6 and Bph9 into elite restorer line 93–11 and development of functional marker for Bph9. Rice 2017, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Singh, A.; Sandhu, N.; Bhandari, A.; Vikram, P.; Kumar, A. Combining drought and submergence tolerance in rice: Marker-assisted breeding and QTL combination effects. Mol. Breed. 2017, 37, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Venuprasad, R.; Atlin, G.N. Genetic analysis of rainfed lowland rice drought tolerance under naturally-occurring stress in eastern India: Heritability and QTL effects. F. Crop. Res. 2007, 103, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venuprasad, R.; Dalid, C.O.; Del Valle, M.; Zhao, D.; Espiritu, M.; Sta Cruz, M.T.; Amante, M.; Kumar, A.; Atlin, G.N. Identification and characterization of large-effect quantitative trait loci for grain yield under lowland drought stress in rice using bulk-segregant analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009, 120, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikram, P.; Swamy, B.; Dixit, S.; Ahmed, H.; Teresa Sta Cruz, M.; Singh, A.; Kumar, A. qDTY1.1, a major QTL for rice grain yield under reproductive-stage drought stress with a consistent effect in multiple elite genetic backgrounds. BMC Genet. 2011, 12, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernier, J.; Kumar, A.; Ramaiah, V.; Spaner, D.; Atlin, G. A Large-Effect QTL for Grain Yield under Reproductive-Stage Drought Stress in Upland Rice. Crop Sci. 2007, 47, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsudin, N.A.A.; Swamy, B.P.M.; Ratnam, W.; Cruz, M.T.S.; Sandhu, N.; Raman, A.K.; Kumar, A. Pyramiding of drought yield QTLs into a high quality Malaysian rice cultivar MRQ74 improves yield under reproductive stage drought. Rice 2016, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Yadaw, R.B.; Mishra, K.K.; Kumar, A. Marker-assisted breeding to develop the drought-tolerant version of Sabitri, a popular variety from Nepal. Euphytica 2017, 213, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, D.N. A Critical Review of Submergence Tolerance Breeding Beyond Sub 1 Gene to Mega Varieties in the Context of Climate Change. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Res. Eng. 2018, 4, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuanar, S.R.; Ray, A.; Sethi, S.K.; Chattopadhyay, K.; Sarkar, R.K. Physiological Basis of Stagnant Flooding Tolerance in Rice. Rice Sci. 2017, 24, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R.K.; Panda, D. Distinction and characterisation of submergence tolerant andsensitive rice cultivars, probedbythefluorescenceOJIP rise kinetics. Funct. Plant Biol. 2009, 36, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Mackill, D.J.; Ismail, A.M. Responses of SUB1 rice introgression lines to submergence in the field: Yield and grain quality. Field Crops Res. 2009, 113, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeraja, C.N.; Maghirang-Rodriguez, R.; Pamplona, A.; Heuer, S.; Collard, B.C.Y.; Septiningsih, E.M.; Vergara, G.; Sanchez, D.; Xu, K.; Ismail, A.M.; et al. A marker-assisted backcross approach for developing submergence-tolerant rice cultivars. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2007, 115, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toojinda, T.; Tragoonrung, S.; Vanavichit, A.; Siangliw, J.L.; Pa-In, N.; Jantaboon, J.; Siangliw, M.; Fukai, S. Molecular breeding for rainfed lowland rice in the Mekong region. Plant Prod. Sci. 2005, 8, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siangliw, M.; Toojinda, T.; Tragoonrung, S.; Vanavichit, A. Thai jasmine rice carrying QTLch9 (SubQTL) is submergence tolerant. Ann. Bot. 2003, 91, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, R.K.; Reddy, J.N.; Sharma, S.G.; Ismail, A.M. Physiological basis of submergence tolerance in rice and implications for crop improvement. Curr. Sci. 2006, 91, 899–905. [Google Scholar]

- Wassmann, R.; Jagadish, S.V.K.; Heuer, S.; Ismail, A.; Redona, E.; Serraj, R.; Singh, R.K.; Howell, G.; Pathak, H.; Sumfleth, K. Chapter 2 Climate Change Affecting Rice Production. The Physiological and Agronomic Basis for Possible Adaptation Strategies, 1st ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 101, ISBN 9780123748171. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, J.R.; Vincent, J.R.; Auffhammer, M.; Moya, P.F.; Dobermann, A.; Dawe, D. Rice yields in tropical/subtropical Asia exhibit large but opposing sensitivities to minimum and maximum temperatures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14562–14567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasulu, N.; Butardo, V.M.; Misra, G.; Cuevas, R.P.; Anacleto, R.; Kishor, P.B.K. Designing climate-resilient rice with ideal grain quality suited for high-temperature stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 1737–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calanca, P.P. Quantification of Climate Variability, Adaptation and Mitigation for Agricultural Sustainability. Quantif. Clim. Var. Adapt. Mitig. Agric. Sustain. 2017, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food security: The challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, M.M.; Takamatsu, T.; Baslam, M.; Kaneko, K.; Itoh, K.; Harada, N.; Sugiyama, T.; Ohnishi, T.; Kinoshita, T.; Takagi, H.; et al. Salt tolerance improvement in rice through efficient SNP marker-assisted selection coupled with speed-breeding. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; Tester, M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 651–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, P.S.; Mishra, B.; Gupta, S.R.; Rathore, A. Reproductive stage tolerance to salinity and alkalinity stresses in rice genotypes. Plant Breed. 2008, 127, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrão, S.; Courtois, B.; Ahmadi, N.; Abreu, I.; Saibo, N.; Oliveira, M.M. Recent updates on salinity stress in rice: From physiological to molecular responses. CRC. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2011, 30, 329–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, M.; Sharifi, H.; Grattan, S.R.; Linquist, B.A. Spatio-temporal salinity dynamics and yield response of rice in water-seeded rice fields. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 195, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; SL, K.; Kumar, V.; Singh, B.; Rao, A.; Mithra SV, A.; Rai, V.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, N.K. Mapping QTLs for Salt Tolerance in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) by Bulked Segregant Analysis of Recombinant Inbred Lines Using 50K SNP Chip. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, T.; Karahara, I.; Katsuhara, M. Salinity tolerance mechanisms in glycophytes: An overview with the central focus on rice plants. Rice 2012, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.J.; Negrão, S.; Tester, M. Salt resistant crop plants. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2014, 26, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deinlein, U.; Stephan, A.B.; Horie, T.; Luo, W.; Xu, G.; Schroeder, J.I. Plant salt-tolerance mechanisms. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanin, M.; Ebel, C.; Ngom, M.; Laplaze, L.; Masmoudi, K. New insights on plant salt tolerance mechanisms and their potential use for breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.C.; Yamaji, N.; Horie, T.; Che, J.; Li, J.; An, G.; Ma, J.F. A magnesium transporter OsMGT1 plays a critical role in salt tolerance in rice. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 1837–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.-H.; Gao, J.-P.; Li, L.-G.; Cai, X.-L.; Huang, W.; Chao, D.-Y.; Zhu, M.-Z.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Luan, S.; Lin, H.-X. A rice quantitative trait locus for salt tolerance encodes a sodium transporter. Nat. Genet. 2005, 37, 1141–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M.J.; de Ocampo, M.; Egdane, J.; Rahman, M.A.; Sajise, A.G.; Adorada, D.L.; Tumimbang-Raiz, E.; Blumwald, E.; Seraj, Z.I.; Singh, R.K.; et al. Characterizing the Saltol quantitative trait locus for salinity tolerance in rice. Rice 2010, 3, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.X.; Zhu, M.Z.; Yano, M.; Gao, J.P.; Liang, Z.W.; Su, W.A.; Hu, X.H.; Ren, Z.H.; Chao, D.Y. QTLs for Na+ and K+ uptake of the shoots and roots controlling rice salt tolerance. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 108, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.T.T.; Le, D.D.; Ismail, A.M.; Le, H.H. Marker-assisted backcrossing (MABC) for improved salinity tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) to cope with climate change in Vietnam. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2012, 6, 1649–1654. [Google Scholar]

- Linh, L.H.; Linh, T.H.; Xuan, T.D.; Ham, L.H.; Ismail, A.M.; Khanh, T.D. Molecular breeding to improve salt tolerance of rice (Oryza sativa L.) in the Red River Delta of Vietnam. Int. J. Plant Genom. 2012, 2012, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregorio, G.B.; Islam, M.R.; Vergara, G.V.; Thirumeni, S. Recent advances in rice science to design salinity and other abiotic stress tolerant rice varieties. Sabrao, J. Breed. Genet. 2013, 45, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, N.N.; Krishnan, S.G.; Vinod, K.K.; Krishnamurthy, S.L.; Singh, V.K.; Singh, M.P.; Singh, R.; Ellur, R.K.; Rai, V.; Bollinedi, H.; et al. Marker aided incorporation of saltol, a major QTL associated with seedling stage salt tolerance, into oryza sativa ‘pusa basmati 1121’. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, R.; Wang, J.; Hui, J.; Bai, H.; Lyu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Huang, R. Improvement of salt tolerance using wild rice genes. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narsai, R.; Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Wu, J.; Shou, H.; Whelan, J. Antagonistic, overlapping and distinct responses to biotic stress in rice (Oryza sativa) and interactions with abiotic stress. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, R.; Fahad, S.; Masood, N.; Rasool, A.; Ijaz, M.; Ihsan, M.Z.; Maqbool, M.M.; Ahmad, S.; Hussain, S.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Plant Growth and Morphological Changes in Rice Under Abiotic Stress. In Advances in Rice Research for Abiotic Stress Tolerance; Woodhead publishing: Campribge, UK, 2019; pp. 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Khush, G.S. Strategies for increasing the yield potential of cereals: Case of rice as an example. Plant Breed. 2013, 132, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Burr, B. International Rice Genome Sequencing Project: The effort to completely sequence the rice genome. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2000, 3, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khush, G.S. What it will take to Feed 5.0 Billion Rice consumers in 2030. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005, 59, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Sandhu, N.; Dixit, S.; Yadav, S.; Swamy, B.P.M.; Shamsudin, N.A.A. Marker-assisted selection strategy to pyramid two or more QTLs for quantitative trait-grain yield under drought. Rice 2018, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhu, N.; Dixit, S.; Swamy, B.P.M.; Raman, A.; Kumar, S.; Singh, S.P.; Yadaw, R.B.; Singh, O.N.; Reddy, J.N.; Anandan, A.; et al. Marker Assisted Breeding to Develop Multiple Stress Tolerant Varieties for Flood and Drought Prone Areas. Rice 2019, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthu, V.; Abbai, R.; Nallathambi, J.; Rahman, H.; Ramasamy, S.; Kambale, R.; Thulasinathan, T.; Ayyenar, B.; Muthurajan, R. Pyramiding QTLs controlling tolerance against drought, salinity, and submergence in rice through marker assisted breeding. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Improved Rice Genotype | Resistance Gene/QTLs | Traits/Diseases/Resistance | Country/Regions | Markers | Donor Parents | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tainung82 | Xa4, xa5, Xa7, xa13 and Xa21 | BLB | Taiwan | Xa4F/4R, RM604F/604R, Xa7F/7-1R/7-2R, Xa13F/13R, and Xa21F/21R | IRBB66 | [76] |

| Jin 23B | Bph3+Bph14+ Bph15+Bph18+Bph20+Bph21 | BPH | China | RM58, RM19324, RM3331, RM28427, RM28561, RM16553, HJ34, RR28561, B212 | PTB33, IR65482–7–216-1-2, IR71033–121-15, B5 | [77] |

| Jalmagna | Xa5, Xa13, a21 | BLB | India | Xa5S (Multiplex), Xa5SR/R (Multiplex), RG136, pTA248 | CRMAS 2232–85 | [28] |

| Pyramided lines | Xa13, Xa21, Xa5, Xa4 | BLB | Npb18, RG556, RG136, pTA248 | IRBB4, IRBB5, IRBB13, IRBB21 | [31,53,61] | |

| CO39 | Pi1, Pita, Piz5 | Blast | Philippines | RZ536, RZ64, RZ612, RG456, RG869, RZ397 | C101LAC, C101A51, C101PKT | [78] |

| Jin 23B | Pi1, Pi2, D12 | Blast | China | RM144, RM224, PI2-4, HC28, RM277, M309 | BL6, Wuyujing 2 | [79] |

| Pusa RH10 | Xa13, Xa21 | BLB | India | RG136, pTA248 | Pusa1460 | [80] |

| -- | Gm-2, Gm-6t | Gall midge | -- | -- | Duokang1, Phalguna | [81] |

| R2381 | Bph3, Bph27 (t) | BPH | China | RH078, RH7, Q31, Q52, Q58, RM471 | Balamawee, Ningjing3, CV 93–11 | [82] |

| Swarna-Sub1 | Pi1, Pi2, Pi54 | Blast | RM224, RM527, RM206, PI54 MAS | Swarna-LT, Swarna-A51 | [83] | |

| PRR78 | Piz5+Pi54 | Rice blast | AP5930, RM206, RM6100 | C101A51, Tetep | [84] | |

| Improved PR106 | Xa5+Xa13+Xa21 | BLB | India | RG 556, RG 136 and pTA248 | IRBB62 | [21] |

| Tapaswini | Xa4+Xa5+Xa13+Xa21 | BLB | India | RG 556, RG 136 and pTA248 | MABC | [20] |

| Improved Lalat | Xa4+Xa5+Xa13+Xa21 | BLB | India | RG 556, RG 136 and pTA248 | IRBB 60 | [21] |

| Improved TNG82 | Xa4, xa5, Xa7, xa13, Xa21 | BLB | Taiwan | Xa4F/4R, RM604F/604R, Xa7F/7-1R/7-2R, Xa13F/13R, and Xa21F/21R | IRBB66 | [21] |

| Mangeumbyeo | Xa4+Xa5+Xa21 | BLB | 10603. T10Dw, MP1 + MP2,U1/I1 | IRBB57 | [85] | |

| MR219, | qDTY2.2 qDTY3.1 qDTY12.1 | Drought | Malaysia | RM236 RM511 RM520 | IR77298-14-1-2-10, IR81896-B-B-195, IR84984-83-15-18-B | [86] |

| MRQ74 | qDTY2.2 qDTY3.1 qDTY12.1 | Drought | Malaysia | RM12460 RM511 RM520 | IR77298-14-1-2-10, IR81896-B-B-195, IR84984-83-15-18-B | [86] |

| ADT 43 | Pi1+Pi2+Pi33+Pi54 | Blast | India | RM206, RM72, RM527, RM1233 | CT 13432-3R | [87] |

| LuoYang69 | Bph6, Bph9 | BPH | China | InD2, RM28466 | 93–11, Pokkali | [88] |

| Pyramided rice lines | Pi2, Pi46, Pita | Rice blast | China | RM224, Ind306, Pita-Ext Pita-Int | H4, Huazhan | [89] |

| PL-(S5-n + f5-n + pf12-j) | S5-n, f5-n, pf12-j | Fertility improvement | China | SNP markers | Dular, 9311 | [90] |

| Rice | qCTF7, qCTF8, qCTF12 | Cold stress | Japan | RM5711, RM22674, | Eikei88223, Suisei | [91] |

| Hua-jing-xian | qCTBB-5, qCTBB-6, qCTS-6, qCTS12 | Cold tolerance | China | RM170, RM589, RM17, RM31 | Nan-yangzhan | [92] |

| Improved Rice Genotype | Pyramided Genes/QTLs | Traits/Diseases/Resistance | Country | Linked Markers | Donor Parents | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD 16 and ADT 43 | xa5, xa13, and Xa21 Pi54, qSBR7-1, qSBR11-1, and qSBR11-2) | BLB, blast, ShB | India | pTA248, Xa13-prom, Xa5, Pi54-MAS RM224, RM336, RM209 | IRBB60, Tetep | [93] |

| Pyramided line | Piz, Pi2, Pi9 and Xa4, Xa5, Xa13, Xa21 | BLB, blast | Malaysia | RM6836, RM8225, RM13, RM21, pTA248 | Putra 1, IRRBB60 | [94] |

| Swarna +drought | Pi9+ Xa4+ xa5+ Xa21+ Bph17+Bph3+Gm4+ Gm8+ qDTY1.1+ qDTY3.1 | Blast, BLB, BPH, drought and gall midge resistance | India | Pi9STS2, Xa4, Xa5DR, Xa13prom, pTA248, RM586, RM8213, Gm4LRR, Gm 8PRP, RM 431, RM 136 | IRBB60, IRBL9, Rathu Heenati, Abhaya and Aganni | [95] |

| Tellahamsa | Xa21, Xa13, Pi54 and Pi1 | BLB, blast | India | pTA248, Xa13 Prom, r Pi54MAS, RM 224 | Improved Samba Mahsuri, Swarnamukhi | [96] |

| JGL1798 | Xa13, Xa21, Pi54 | BLB, blast | India | Xa13-prom, pTA248, Pi54-MAS | Improved Samba Mahsuri, NLR145 | [97] |

| RPHR-1005 | Xa21, Gm4, Gm8, Rf3, Rf4 | BLB, gall midge, fertility restorer genes | India | pTA248, LRR-del, PRP, DRRM-Rf3–10, DRCG-RF4–14 | SM1, SM2 | [98] |

| Improved Lalat (Recurrent Parent) | Pi2, Pi9, Gm1, Gm4, Sub1 Saltol | Blast, gall midge, submergence, salt tolerance | India | RM444, RM547, RG64 SUB1BC2 RM10745 | C1O1A51, WHD-1S-75-1-127 Kavya, Abhaya, FR13A FL478 | [20,24,66,78,99,100,101,102,103,104,105] |

| MH725 | Xa21, Xa4, Xa27, Sub1A, Pi9, Badh2.1, Badh2 | Blast, BLB, submergence Aromatic fragrance | China | M265, M355, NBS2-1, RM23887, RM224, RM21, M124 | KDML105, IRBB27, 75-1-127, IR64 | [106,107] |

| Pink3 | Genes (Sub1A-C, SSIIa, Xa5, Xa21, TPS), QTLs (qBph3, qBL1, qBL11) | Submergence, BLB, blast, BPH | Thailand | SNP and SSR markers | CholSub1, Xa497, RBPiQ, Bph162 | [108] |

| Wuyujin3 | Stv-bi Wx-mq | Low amylase content, rice strip disease | China | ST-10, Wx-mq-OF, Wx-mq-IR | Kanto 194 | [109] |

| Junam | PH18+Xa40+Xa3+Pib+Pik+qSTV11SG | BPH, BB, blast, SSV | 7312.T4A+HinfI, ID55.WA3, RM1233, 10571.T7+HinfI, NSB, K6415, Indel7 | IR65482–7–216-1-2 | [110] | |

| Cultivar 9311 | BXa21, Sub1A, Pi9 | LB, blast and submergence | China | RM224,5198 | WH21, IR64, 1892S, Guangzhan 63S, IR31917 | [107,111,112] |

| Jinbubyeo | Xa4, Xa5, Xa21, Pi40, Bph18 | BLB, rice blast, brown planthopper | China | MP1+MP2, 10603, T10Dw, U1+I1, 9871.T7E2b and 7312.T4A | IRBB57, IR65482-4-136-2-2, IR65482-7-216-1-2 | [85,113,114,115] |

| Pyramided lines | tms2, tgms, tms5 | Thermosensitive genetic male sterility (TGMS) | Philippines | RM257, RM174, RM11 | DQ200047-21, Norin PL 12, SA2 | [116] |

| Pyramided lines | Xa21, The Bt fusion gene, The RC chitinase gene | BLB, yellow stem borer, sheath blight | Philippines | SSR markers | TT103, TT9 | [117] |

| Shengdao15, Shengdao16, Xudao3 | Bph14, Bph15 Stv-b | Brown planthopper, rice stripe disease | China | B14, B15, S1 | B5 | [118] |

| Hua1015S | Pi2, Xa23 | Blast, BLB | China | RM527, Ind M-Xa23 | GZ63-4S, VE6219, HBQ810 | [119] |

| Hom Mali 821 | Sub1, Qbph12 | Submergence and BPH | Thailand | R10783indel, RM277, RM260 | IR49830, ABHAYA RGD9903 RGD9905) | [120] |

| Pyramided lines | Sub1, badh2, qBl1 and qBl11 | Submergence, blast Strong fragrance | Thailand | R10783indel, RM212-RM319, RM224-RM144, Aromarker | TDK303 IR85264GD07529 | [121] |

| Junam | Xa3, Xa4 and QTL (qCT11) | BLB and cold tolerance | Korea | RM1233, RM3577, RM4112, RM5766, RM224 | IR72 | [122] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haque, M.A.; Rafii, M.Y.; Yusoff, M.M.; Ali, N.S.; Yusuff, O.; Datta, D.R.; Anisuzzaman, M.; Ikbal, M.F. Recent Advances in Rice Varietal Development for Durable Resistance to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses through Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910806

Haque MA, Rafii MY, Yusoff MM, Ali NS, Yusuff O, Datta DR, Anisuzzaman M, Ikbal MF. Recent Advances in Rice Varietal Development for Durable Resistance to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses through Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding. Sustainability. 2021; 13(19):10806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910806

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaque, Md Azadul, Mohd Y. Rafii, Martini Mohammad Yusoff, Nusaibah Syd Ali, Oladosu Yusuff, Debi Rani Datta, Mohammad Anisuzzaman, and Mohammad Ferdous Ikbal. 2021. "Recent Advances in Rice Varietal Development for Durable Resistance to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses through Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding" Sustainability 13, no. 19: 10806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910806

APA StyleHaque, M. A., Rafii, M. Y., Yusoff, M. M., Ali, N. S., Yusuff, O., Datta, D. R., Anisuzzaman, M., & Ikbal, M. F. (2021). Recent Advances in Rice Varietal Development for Durable Resistance to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses through Marker-Assisted Gene Pyramiding. Sustainability, 13(19), 10806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910806