Leadership Roles for Sustainable Development: The Case of a Malaysian Green Hotel

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methods

4. Barriers of Green Hotel Approach in Malaysia

Green Components of Frangipani Hotel

5. Green Hotel Practice Based on Science and Technology

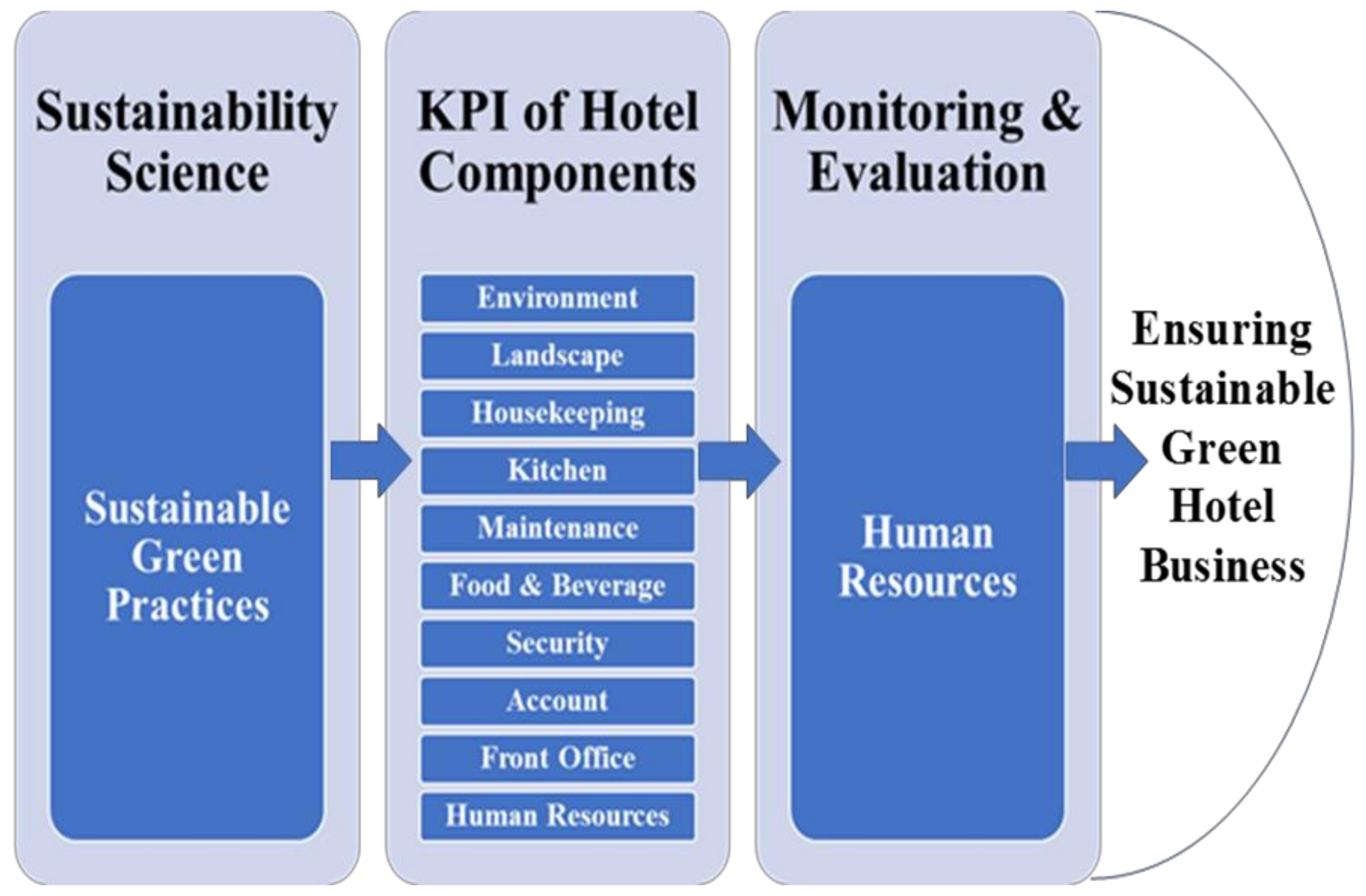

6. Sustainability Science to Promote Green Hotel

7. Leadership Roles of Green Frangipani Hotel

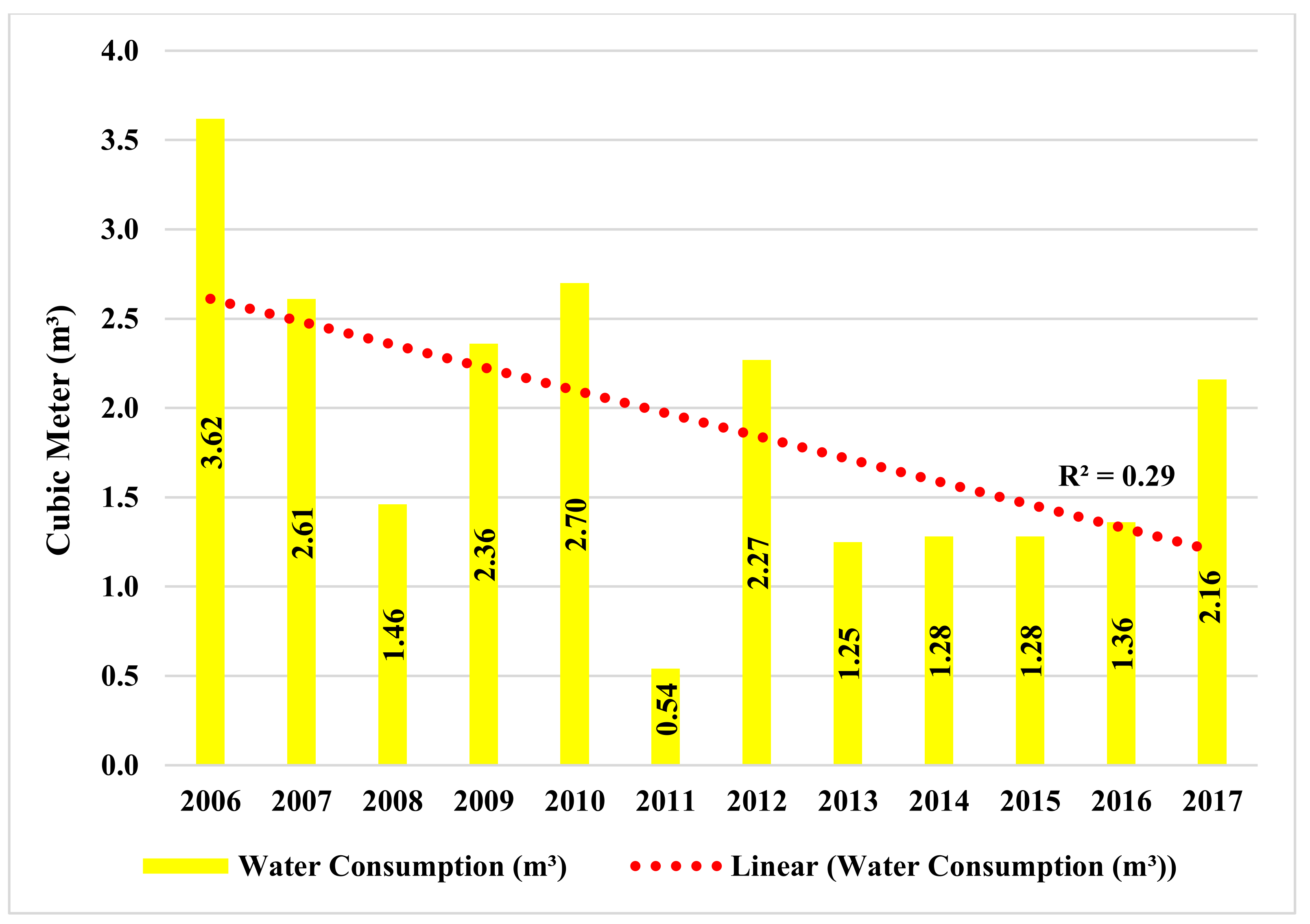

7.1. Environmental Sustainability

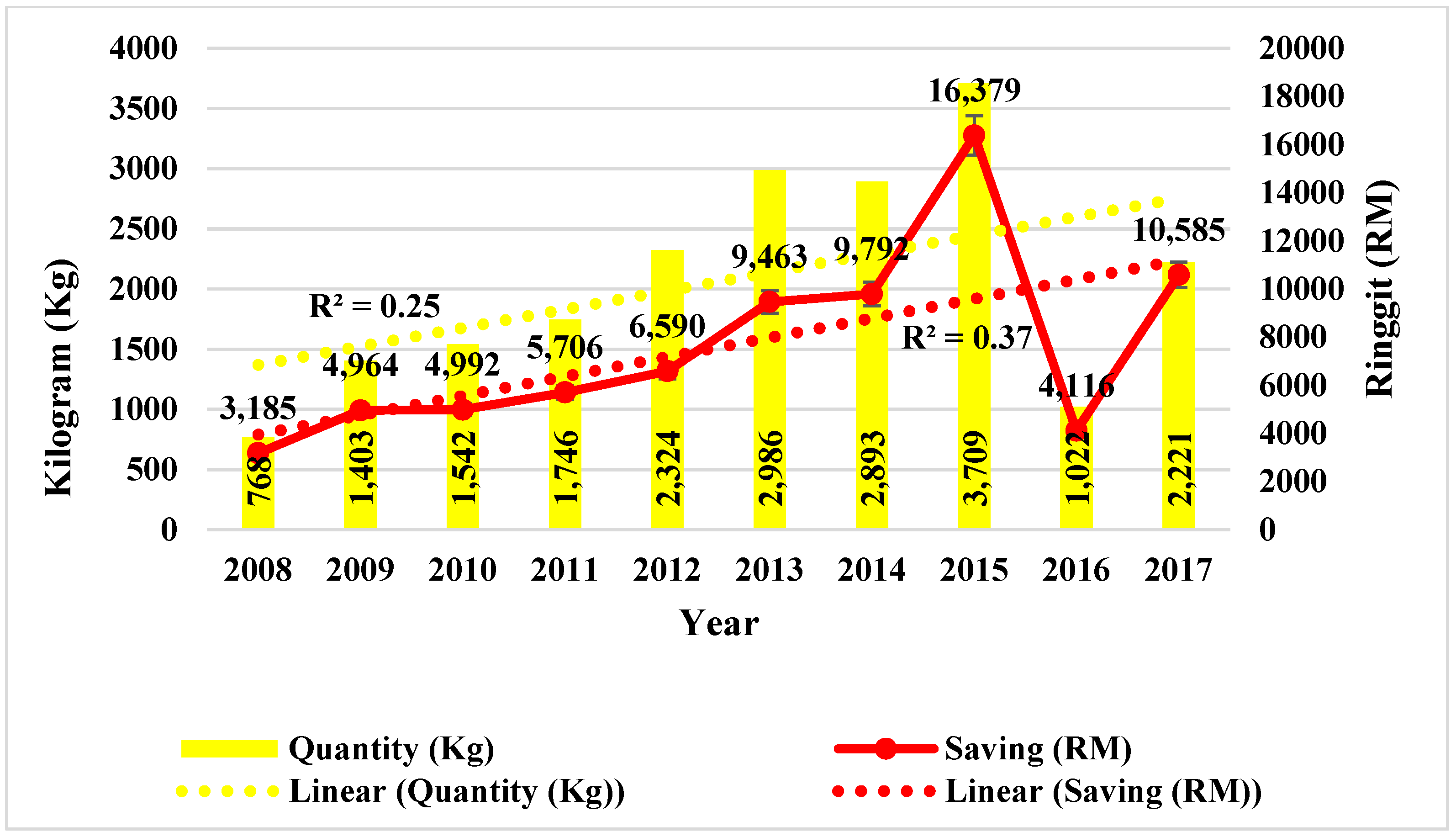

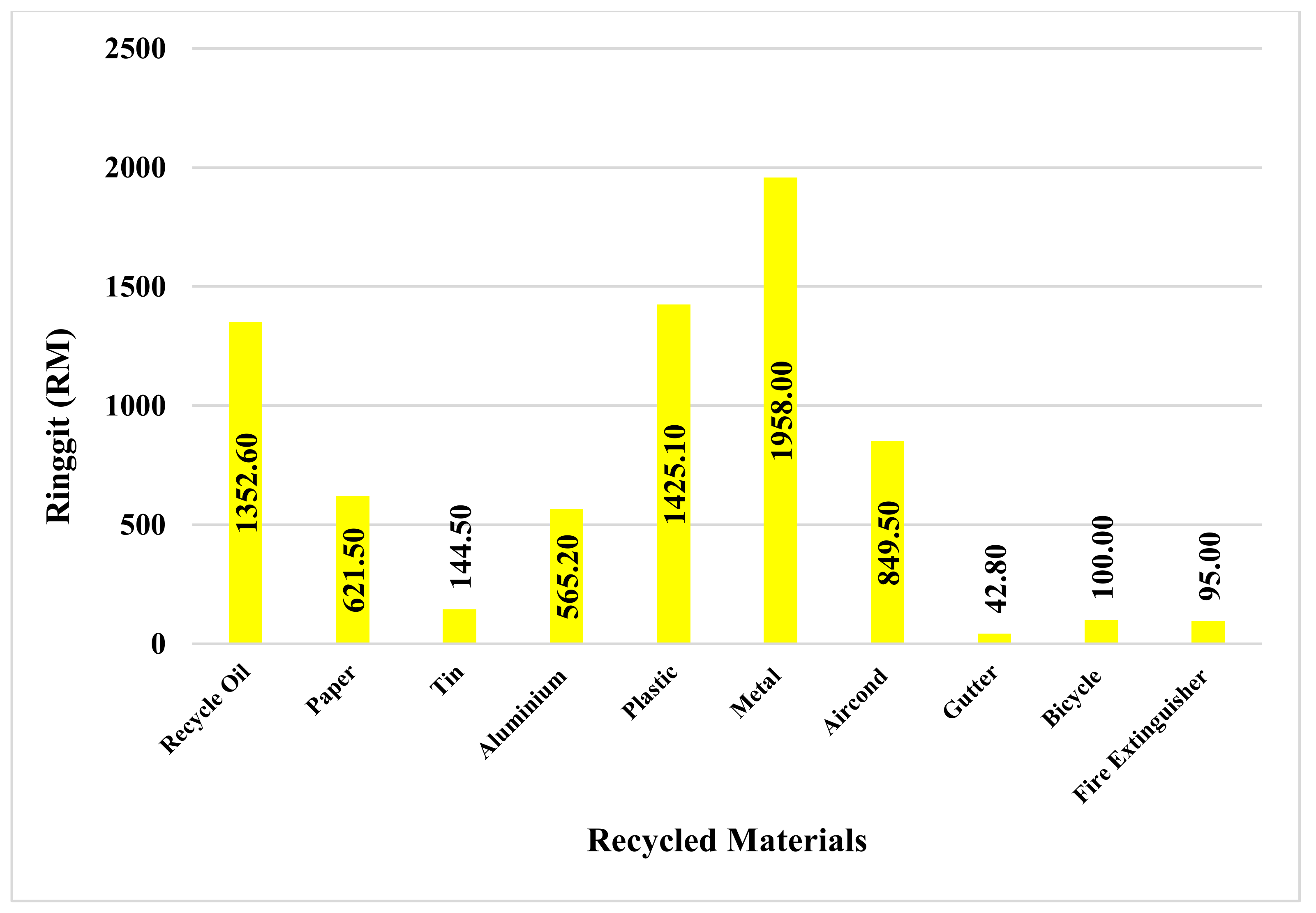

7.2. Economic Sustainability

7.3. Social Sustainability

7.4. Cultural Sustainability

8. Monitoring and Evaluation of Green Hotel

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hermann, R.R.; Bossle, M.B. Bringing an entrepreneurial focus to sustainability education: A teaching framework based on content analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 119038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Dhar, R.L. Effect of green transformational leadership on green creativity: A study of tourist hotels. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A.H.; Hassan, T.H.; Dief, E.; Moustafa, M. A Description of Green Hotel Practices and Their Role in Achieving Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.H.J.; Chen, C.D. Does sustainability index matter to the hospitality industry? Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Nguyen, T.H.; Armstrong, A. Developing collective leadership capacity to drive sustainable practices: Destination case of leadership development in Australia. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulou, E.; Chatzimentor, A.; Maestre-Andrés, S.; Requena-i-Mora, M.; Pizarro, A.; Bormpoudakis, D. Reviewing 15 years of research on neoliberal conservation: Towards a decolonial, interdisciplinary, intersectional and community-engaged research agenda. Geoforum 2021, 124, 236–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus Pacheco, D.A.; ten Caten, C.S.; Jung, C.F.; Sassanelli, C.; Terzi, S. Overcoming barriers towards Sustainable Product-Service Systems in Small and Medium-sized enterprises: State of the art and a novel Decision Matrix. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 903–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.C. Green marketing orientation: Achieving sustainable development in green hotel management. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 722–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezakati, H.; Hosseinpour, M. Green Tourism Practices in Malaysia; Hassan, H., Nezakati, H., Eds.; Selected Issues in Hospitality and Tourism Sustainability; Universiti Putra Malaysia Press: Serdang, Malaysia, 2014; ISBN 978-967-344-430-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rainforest Alliance. FAQ: What Is the Difference Between Green, Eco-, and Sustainable Tourism? 2016. Available online: https://www.rainforest-alliance.org/faqs/difference-between-eco-tourism-green-sustainable-travel (accessed on 4 March 2019).

- Lim, C.K.; Tan, K.L.; Hambira, N. An Investigation on Level of Public Awareness of Green Homes in Malaysia through Web-Based Illustrations. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 2016, 020074. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C.K.; Tan, K.L.; Hambira, N. A Proposed Guideline with Building Information Modelling (BIM) for Virtual Transformation of Traditional Housing to Green Housing. Int. J. Sup. Chain. Mgt. 2018, 7, 485–491. [Google Scholar]

- IES. What Is Ecotourism?. The International Ecotourism Society. 2019. Available online: https://ecotourism.org/what-is-ecotourism/ (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Brown, M. Environmental policy in the hotel sector: “green” strategy or stratagem? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 1996, 8, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jai, T.M.; Li, X. Guests’ perceptions of green hotel practices and management responses on TripAdvisor. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2016, 7, 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.J.; Lee, J.S. Empirical investigation of the roles of attitudes toward green behaviors, overall image, gender, and age in hotel customers’ eco-friendly decision-making process. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.C.; Chang, H.H.; Chang, A. Consumer personality and green buying intention: The mediate role of consumer ethical beliefs. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP & UNWTO. Tourism in the Green Economy–Background Report; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2012; Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284414529 (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Jones, C. Scenarios for greenhouse gas emissions reduction from tourism: An extended tourism satellite account approach in a regional setting. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Transforming Tourism for Climate Action; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2021; Available online: https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-development/climate-change (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- UNESCO. Langkawi UNESCO Global Geopark (Malaysia); United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural OrganizationL: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/earth-sciences/unesco-global-geoparks/list-of-unesco-global-geoparks/malaysia/langkawi/ (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Komoo, I. Langkawi UNESCO Global Geopark. In Rising to the Challenge: Malaysia’s Contribution to SDGs; Mokhtar, M., Lee, K.E., Sivapalan, S., Eds.; Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia: Bangi, Malaysia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- GoogleEarth. Map of the Frangipani Langkawi Resort; Google Earth Pro: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yusof, Z.B.; Jamaludin, M. Green approaches of Malaysian green hotels and resorts. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 85, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gupta, A.; Dash, S.; Mishra, A. All that glitters is not green: Creating trustworthy ecofriendly services at green hotels. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.D.M.; Álvarez-Gil, M.J. Green Entrepreneurship in Tourism. In The Emerald Handbook of Entrepreneurship in Tourism, Travel and Hospitality; Marios, S., Ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogmartens, R.; Eyckmans, J.; Van Passel, S. A Hotelling model for the circular economy including recycling, substitution and waste accumulation. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 128, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular economy: The concept and its limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, M.; Ahmed, M.F.; Lee, K.E.; Lubna, A.; Goh, C.T.; Rahmah, E.; Wong, A.K.H. Achieving sustainable coastal environment in Langkawi, Malaysia. Borneo J. Mar. Sci. Aquac. 2017, 1. Available online: http://jurcon.ums.edu.my/ojums/index.php/BJoMSA (accessed on 10 March 2019).

- Burns, J.M. Leadership; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Katou, A.A. Transformational leadership and organisational performance: Three serially mediating mechanisms. Empl. Relat. 2015, 37, 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, S.; Akram, A. Transformational leadership and organizational performance: The mediating role of organizational innovation. SEISENSE J. Manag. 2018, 1, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Majeed, N.; Ramayah, T.; Mustamil, N.M.; Nazri, M.; Jamshed, S. Transformational leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: Modeling emotional intelligence as mediator. Manag. Mark. 2017, 12, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khalili, A. Transformational leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: The moderating role of emotional intelligence. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 1004–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.B. Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychol. Rev. 1913, 20, 158–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cherry, K. History and Key Concepts of Behavioral Psychology; Verywell: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.verywellmind.com/behavioral-psychology-4157183#citation-3 (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- CFI. Leadership Theories. Vancouver, Canada: Corporate Finance Institute. 2021. Available online: https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/careers/soft-skills/leadership-theories/ (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M. Do value-attitude-behavior and personality affect sustainability crowdfunding initiatives? J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner-Gulland, E.J.; Addison, P.; Arlidge, W.N.; Baker, J.; Booth, H.; Brooks, T.; Bull, J.W.; Burgass, M.J.; Ekstrom, J.; zu Ermgassen, S.O.; et al. Four steps for the Earth: Mainstreaming the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. One Earth 2021, 4, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Campo, A.G.; Gazzola, P.; Onyango, V. The mutualism of strategic environmental assessment and sustainable development goals. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 82, 106383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantabutra, S.; Ketprapakorn, N. Toward a theory of corporate sustainability: A theoretical integration and exploration. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potdar, B.; Garry, T.; McNeill, L.; Gnoth, J.; Pandey, R.; Mansi, M.; Guthrie, J. Retail employee guardianship behaviour: A phenomenological investigation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashar, A.; Vijaya, S.M. A bibliometric and content analysis of sustainable development in small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, T.; Gee, K. Governance as a framework to theorise and evaluate marine planning. Mar. Policy 2020, 120, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zach, F.J.; Nicolau, J.L.; Sharma, A. Disruptive innovation, innovation adoption and incumbent market value: The case of Airbnb. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 80, 102818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Q. Does participating in the standards-setting process promote innovation? Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 63, 101532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, J.; Wessels, J.A.; Douglas, A.; Hughes, M.; Morrison-Saunders, A. The potential contribution of environmental impact assessment (EIA) to responsible tourism: The case of the Kruger National Park. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 32, 100557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardas, B.B.; Mangla, S.K.; Raut, R.D.; Narkhede, B.; Luthra, S. Green talent management to unlock sustainability in the oil and gas sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 850–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinillo, S.; Anaya-Sánchez, R.; Morrison, A.M.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Smart city communication via social media: Analysing residents’ and visitors’ engagement. Cities 2019, 94, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisters, S.R.; Vihinen, H.; Figueiredo, E. Place based transformative learning: A framework to explore consciousness in sustainability initiatives. Emot. Space Soc. 2019, 32, 100578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barani, S.; Alibeygi, A.H.; Papzan, A. A framework to identify and develop potential ecovillages: Meta-analysis from the studies of world’s ecovillages. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 43, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, J.; Bond, A.; Cameron, C.; Retief, F.; Morrison-Saunders, A. Are current effectiveness criteria fit for purpose? Using a controversial strategic assessment as a test case. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2018, 70, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tasci, A.D. Testing the cross-brand and cross-market validity of a consumer-based brand equity (CBBE) model for destination brands. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C.J. When markets reset, will we regain? Planning lessons from across the Atlantic Ocean. Land Use Policy 2017, 65, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerin, T.F. Evaluating expected and comparing with observed risks on a large-scale solar photovoltaic construction project: A case for reducing the regulatory burden. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 74, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Király, G.; Köves, A.; Balázs, B. Contradictions between political leadership and systems thinking. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.H.; Morrison-Saunders, A.; Grimstad, S. Operating small tourism firms in rural destinations: A social representations approach to examining how small tourism firms cope with non-tourism induced changes. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Broman, G.; Robèrt, K.H.; Collins, T.J.; Basile, G.; Baumgartner, R.J.; Larsson, T.; Huisingh, D. Science in support of systematic leadership towards sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, T.J. Review of the twenty-three year evolution of the first university course in green chemistry: Teaching future leaders how to create sustainable societies. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harpur, E.; Walker, E.G. Qualification of safety biomarkers for use in drug development: What has been achieved and what is the path forward? Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2017, 4, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X. The future of ASEAN energy mix: A SWOT analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasavan, S.; Mohamed, A.F.; Halim, S.A. Drivers of food waste generation: Case study of island-based hotels in Langkawi, Malaysia. Waste Manag. 2019, 91, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfithri, R.; Mokhtar, M.B.; Abdullah, M.P. Water and environmental sustainability in Langkawi UNESCO Global Geopark, Malaysia: Issues and challenges towards sustainable development. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhir, M.S.A.M.; Amir, A.A.; Mokhtar, M.; Hooi, A.W.K. Constructed Wetland for Wastewater Treatment: A Case Study at Frangipani Resort, Langkawi. Int. J. Malay World Civilis. 2016, 4, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Akhir, M.S.A.M.; Amir, A.A.; Mokhtar, M.B. Nutrients and Pollutants Removal in Small-Scale Constructed Wetland in Frangipani Resort Langkawi, Malaysia. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2017, 16, 569–577. [Google Scholar]

- Kasim, A.; Gursoy, D.; Okumus, F.; Wong, A. The importance of water management in hotels: A framework for sustainability through innovation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 1090–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Cheng, C.C. Less is more: A new insight for measuring service quality of green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 68, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S. Barriers to EMS in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KamalulAriffin, N.S.; Khalid, S.N.A.; Wahid, N.A. The barriers to the adoption of environmental management practices in the hotel industry: A study of Malaysian hotels. Bus. Strategy Ser. 2013, 14, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J.; Oetzel, J.; Starik, M. Business responses to environmental and social protection policies: Toward a framework for analysis. Policy Sci. 2009, 42, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutional theory: Contributing to a theoretical research program. In Great Minds in Management: The Process of Theory Development; Smith, K.G., Hitt, M.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; Volume 37, pp. 460–484. [Google Scholar]

- Yusof, Z.B.; Jamaludin, M. Barriers of Malaysian green hotels and resorts. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 153, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manaktola, K.; Jauhari, V. Exploring consumer attitude and behaviour towards green practices in the lodging industry in India. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.A.A.; Foong, S.Y.; Ong, T.S.; Senik, R.; Attan, H.; Arshad, Y. Intensity of market competition, strategic orientation and adoption of green initiatives in Malaysian public listed companies. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2018, 67, 1334–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, B.; Caldas, M.G. The use of green criteria in the public procurement of food products and catering services: A review of EU schemes. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 20, 1905–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Broadening the Application of the Sustainability Science Approach; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO): Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://en.unesco.org/sustainability-science/guidelines (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Han, H.; Kim, Y. An investigation of green hotel customers’ decision formation: Developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezan, O.; Raab, C.; Yoo, M.; Love, C. Sustainable hotel practices and nationality: The impact on guest satisfaction and guest intention to return. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Hotels Association (GHA). Why Should Hotels Be Green? 2019. Available online: http://greenhotels.com/index.php (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Kaiser, F.G.; Oerke, B.; Bogner, F.X. Behavior-based environmental attitude: Development of an instrument for adolescents. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, M.; Baloglu, S. Hotel guests’ preferences for green hotel attributes. In Hospitality Management; The University of San Francisco: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008; Available online: https://repository.usfca.edu/hosp/5 (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Ahmed, M.F.; Mokhtar, M.B.; Alam, L.; Mohamed, C.A.R.; Ta, G.C. Non-carcinogenic Health Risk Assessment of Aluminium Ingestion Via Drinking Water in Malaysia. Expo. Health 2019, 11, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.F.; Mokhtar, M.; Alam, L.; Ta, G.C.; Lee, K.E.; Rasyikah, M.K. Recognition of Local Authority for Better Management of Drinking Water at the Langat River Basin, Malaysia. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B.; Taheri, B.; Giritlioglu, I.; Gannon, M.J. Tackling food waste in all-inclusive resort hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makopondo, R.O.; Rotich, L.K.; Kamau, C.G. Potential Use and Challenges of Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment and Conservation in Game Lodges and Resorts in Kenya. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 9184192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Salazar, R.; Mora-Aparicio, C.; Alfaro-Chinchilla, C.; Sasa-Marín, J.; Scholz, C.; Rodríguez-Corrales, J.Á. Biogardens as constructed wetlands in tropical climate: A case study in the Central Pacific Coast of Costa Rica. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 658, 1023–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertenat, A.; Diener, S.; Zurbrügg, C. Black Soldier Fly biowaste treatment–Assessment of global warming potential. Waste Manag. 2019, 84, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.Y.; Chiu, S.L.; Lo, I.M. Effects of moisture content of food waste on residue separation, larval growth and larval survival in black soldier fly bioconversion. Waste Manag. 2017, 67, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masullo, A. Organic wastes management in a circular economy approach: Rebuilding the link between urban and rural areas. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 101, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, S.; Laso, J.; Margallo, M.; Aldaco, R.; Rivero, M.J.; Irabien, Á.; Ortiz, I. LCA of greywater management within a water circular economy restorative thinking framework. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 621, 1047–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, M.; Tajam, J.; Wagiman, S. Determination of the Sediment Contamination Level in Dangli Waters of Langkawi UNESCO Global Geopark, Kedah, Malaysia. Sains Malays. 2019, 48, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, M.B.; Ta, G.C.; Murad, M.W. An essential step for environmental protection: Towards a sound chemical management system in Malaysia. J. Chem. Health Saf. 2010, 17, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, M.; Awaluddin, A.; Tan, M.; Yasin, Z. Trace Metals in Langkawi coral and sediment: A study using AAS and XRF. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2001, 7, 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.F. Hotel chain affiliation as an environmental performance strategy for luxury hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Adger, W.N.; Agnolucci, P.; Blackstock, J.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Cox, P.M. Health and climate change: Policy responses to protect public health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1861–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; de Groot, R.; Sutton, P.; Van der Ploeg, S.; Anderson, S.J.; Kubiszewski, I.; Turner, R.K. Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 26, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, S.; Gatto, K.; Smoller, M. Consumer knowledge about food production systems and their purchasing behavior. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 20, 2871–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Martinez, A.; Cegarra-Navarro, J.G.; Garcia-Perez, A.; Wensley, A. Knowledge agents as drivers of environmental sustainability and business performance in the hospitality sector. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminudin, N. Corporate social responsibility and employee retention of ‘Green’Hotels. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 105, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aniah, P.; Yelfaanibe, A. Environment, development and sustainability of local practices in the sacred groves and shrines in Bongo District: A bio-cultural study for environmental management in Ghana. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2017, 20, 2487–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliadis, C.A.; Fotiadis, A.; Piper, L.A. Analysis of rural tourism websites: The case of Central Macedonia. Tour. Int. Multidiscip. J. Tour. 2013, 8, 247–263. [Google Scholar]

- Accenture. Long-Term Growth, Short-term Differentiation and Profits from Sustainable Products and Services: A Global Survey of Business Executives. 2012. Available online: http://www.ddline.fr/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Accenture-Long-Term-Growth-Short-Term-Differentiation-and-Profits-from-Sustainable-Products-and-Services1.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2019).

| Author and Year | Country | Objectives | Variables | Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim and Hall, 2021 [38] | Korea | To utilize theories of value–attitude–behavior (VAB) model and personality to investigate Korean consumer crowdfunding behavior for sustainability initiatives. | Value, attitude, personal norm, and social norm on sustainability, and participation in sustainability crowdfunding. | Value–attitude–behavior (VAB) model. | Value has substantial impacts on attitude, personal norm, and social norm. Attitude, personal norm, and social norm on consumer crowdfunding sources are found to have positive impacts on participation. |

| Apostolopoulou et al., 2021 [6] | Global | To explore the principal ways in which conservation is neoliberalized in practice. | Peer-reviewed scholarship, key processes of neoliberalization. | Descriptive statistics and thematic content analysis. | A shift towards a decolonial, interdisciplinary, intersectional, community-engaged approach and an in-depth encounter with everyday practices of resistance is important for conservation in neoliberalized principal. |

| Milner-Gulland et al., 2021 [39] | England | To restore nature while meeting human needs requires a bold vision. | National governments, sub-national levels, companies, and individuals. | Mitigation and Conservation Hierarchy. | The Mitigation and Conservation Hierarchy supports the choice of actions to conserve and restore nature, and evaluation of the effectiveness of those actions, across sectors and scales. |

| Del Campo et al., 2020 [40] | Ireland, Italy, and Kenya | To explore the extent to which the community has reflected upon SEA’s role in delivering the SDGs. | Strategic Environmental Assessment. | Systematic literature review. | Operationalization of SDGs provides training for a more proactive integration of objectives and targets of the Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). |

| Hermann and Bossle, 2020 [1] | Global | To explore entrepreneurial competences in higher education in order to be taught in sustainability education programs. | Teaching–learning approaches and external collaboration. | Bibliometric method. | Education for sustainable development across educational programs brings solutions for complex community problems by engaging businesses and consumers related to sustainability issues. |

| Kantabutra and Ketprapakorn, 2020 [41] | Global | To explore sustainability organizational culture comprising sustainability vision and values leads to emotional commitment among organizational members. | Perseverance, resilience development, moderation, geosocial development, and sharing. | Qualitative study. | Corporate sustainability asserts that the sustainability organizational culture comprising sustainability vision and values leads to emotional commitment among organizational members to attain the vision. |

| Potdar et al., 2020 [42] | New Zealand | To examine how employers’ corporate social responsibility involvement influences employee proclivity towards guardianship behavior in shoplifting prevention. | Employers’ corporate social responsibility. | Semi-structured interview. | A reduction in retail crime contributes towards positive relationships among key stakeholders such as supermarkets, their employees, and society at large based on the social, environmental, and employee welfare practices of supermarkets. |

| Prashar and Vijaya, 2020 [43] | Global | To present a state of the art literature review on sustainable development in SMEs. | Small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). | Systematic literature review. | The applications of key management tools (such as tools for CSR management, environment management, LCA (life-cycle assessments), and sustainability evaluation indicators) are helpful for managers to integrate sustainability into SMEs’ business strategy. |

| Stojanovic and Gee, 2020 [44] | Global | To understand whether marine planning really is leading towards sustainability. | Marine spatial planning. | Reviews analytical debates and empirical evidence. | This paper outlines five key major theoretical approaches for governance and reviews analytical debates and empirical findings of marine planning using those approaches. |

| Su and Chen, 2020 [4] | USA | To analyze whether Dow Jones Sustainability North America Index (DJSI) generates short- and long-run impacts on hospitality firms’ financial values. | Dow Jones Sustainability North America Index (DJSI). | Event study model. | Institutional ownership paves the way to develop new socially responsible investment strategies and ESG (environmental, social, and corporate governance)-oriented practices that help consolidate tourism-related firms’ financial performance and positively benefit society. |

| Zach et al., 2020 [45] | Global | To analyze the market value impact of actions taken in response to disruptive innovation. | Incumbent tourism firms. | Event study. | Adoption speeds, that is, first vs. late adoption, make a difference as the former is awarded a significant increase in market value. |

| Zhang et al., 2020 [46] | China | To explore the positive effect of standards-setting involvements on corporate innovation in China. | Effect of standards-setting involvements on corporate innovation. | Empirical evidence. | Standards-setting involvements foster innovation mainly through improving firms’ R&D efficiency, reducing financial constraints, and inducing collaborative innovation. |

| Pope et al., 2019 [47] | South Africa | To find out parallels in the discourses of EIA and responsible tourism. | Sustainable and responsible tourism. | Focused literature review. | A framework comprising five characteristics that EIA should embody to maximize its contribution to responsible tourism. |

| Gardas et al., 2019 [48] | India | To analyze the barriers to sustainable human resource management with a focus on talent management in the Indian oil and gas sector. | High attrition rate, lack of talent supply from the academic institutes, insufficient knowledge transfer. | Interpretive structural modeling technique. | ‘Uncertain career growth’, ‘industry dynamism’, and ‘lack of training programs’ are the significant barriers to corporate sustainability. |

| Molinillo et al., 2019 [49] | Spain | To explore a unique conceptual model and methodology incorporating popularity, commitment, and virality to measure the social media engagement with residents and visitors of smart cities. | Popularity, commitment, and virality. | Digital content analysis. | Spanish smart cities have considerable scope to improve their use of social media to enhance their communications and branding while prioritizing emotional messages and business events. |

| de Jesus Pacheco et al., 2019 [7] | Global | To identify the main barriers involving the transition towards sustainable product–service systems in manufacturing SMEs as well as the strategies to overcome them. | Financial resources, competences, mentality, and resistance to change. | Systematic literature review. | Internal barriers associated with intrinsic characteristics of SMEs become still more sensitive during the transition (e.g., limited financial resources, the lack of competences, follower mentality, and resistance to change). |

| Pisters et al., 2019 [50] | Global | To research the extent to which people involved in place-based sustainability initiatives develop an ecological consciousness. | (Re-)connection, (self-)compassion, and creativity. | Critical literature review. | Transformative learning (TL) that fosters a shift in consciousness towards a more ecological approach is an inherently place-based phenomenon. |

| Barani et al., 2018 [51] | Global | To explore world’s ecovillages for achieving a framework that can provide a common mental model for developing available ecovillages. | Ecovillage, sustainable society, intentional communities, case study, and eco-community. | Qualitative meta-analysis, systematic literature review. | Analyzing the integrity of the ecovillage is an interdisciplinary subject, which requires a variety of expertise to address the aspects such as energy, building design, water, agriculture, and so on. Therefore, evaluating all dimensions and characteristics of ecovillages is beyond the experience of a researcher. |

| Pope et al., 2018 [52] | Australia | To test the broader utility of the sustainability assessment effectiveness framework by applying it to a controversial strategic assessment case study. | Procedural, substantive, trans-active, normative, pluralism, and knowledge and learning. | Document review. | The concept of substantive effectiveness should be expanded to incorporate the unintended consequences of impact assessment. |

| Tasci, 2018 [53] | USA | To analyze consumer/customer-based brand equity models for different segments based on nationality, gender, and past visitation. | Consumer/customer-based brand equity models. | Path analysis. | Familiarity and image were the two most prominent components explaining loyalty in both consumer-/customer-based brand equity models, although both consumer value and brand value also had some mediating effects on loyalty. |

| Balsas, 2017 [54] | USA and Portugal | To examine regional planning for territorial coherence. | Urban development patterns, regulatory and administrative planning traditions, socio-economic and cultural systems. | Comparative analysis. | Anticipatory regional planning has the capacity to adapt to changing conditions in order to maintain and develop more sustainable and resilient territories. |

| Guerin, 2017 [55] | Australia | To confirm and clarify the nature of environmental and community risks to be expected on Australian solar photovoltaic construction sites. | Engineering procurement construction (EPC), end-of-life packaging materials (EOLPMs). | Desktop study. | Majority of the risks actually experienced in the field during the construction phase. |

| Király et al., 2017 [56] | Global | To understand how leaders acquire and process information and how their systems thinking perspectives guide their cognitive procedures when turning pieces of information into policy interventions. | Individual filter (political leaders’), political filter, institutional filter. | Selectorate theory. | Under the current rules of politics, political leaders’ main motivation is to increase the chances of their own political survival, drawing upon their systemic understanding. |

| Lai et al., 2017 [57] | Australia | To explore owners and managers of small tourism firms in relation to destinations and non-tourism-induced changes. | Lifestyle goals. | Semi-structured interviews. | Coping in mining towns is impeded by feelings of powerlessness, perceived uncertainties, and distrust in both government and industry. |

| Broman et al., 2017 [58] | Global | To explore science and leadership in order to mitigate threats and transform current societies into sustainable societies. | Science-based perspective on leadership towards sustainability. | Thematic review. | Science cannot only help people to solve specific problems, but it can provide a solid, strategic systems-derived overview that is relevant to all of humanity and actor towards sustainability. |

| Collins, 2017 [59] | Global | To explore tertiary education in order to fit in the chemical sustainability. | Green and sustainability bookcase, technology sustainability campus, code of sustainability ethics for leaders. | Thematic review. | Cultural blockades against the rational advancement of sustainability within chemical and sustainability transformation should address technical content appropriately to educate leaders for a sustainable world. |

| Harpur and Walker, 2017 [60] | USA | To explore novel safety biomarkers in different phases of drug development by regulators from preclinical safety assessment to clinical trials. | Safety biomarkers, regulatory qualifications. | Thematic review. | Networking and collaboration among stakeholders, including less formal or time-intensive interactions by regulators, e.g., FDA contributes to significant decision-making and sustained leadership. |

| Shi, 2016 [61] | South East Asian Countries | To assesses competing outlooks for energy mix to move toward a green energy mix. | Green energy strategies. | Thematic review and SWOT analysis. | Green energy strategies will require sustained leadership, political determination, and concrete actions from stakeholders, in particular, national governments across the region. |

| Sectors | Challenges | Current Practices |

|---|---|---|

| Environment | No book written on sustainable green hotel practices. | Frangipani management has recorded more than 200 green hotel activities from around the world to be practiced locally. |

| Landscape | Initially, staff cannot link the environment as an important part of social and economic advancement. | Training programs are ongoing to address environmental, social, and economic balance. |

| Housekeeping | Most guests are not aware of green housekeeping practices, which leads to unnecessary washing of towel, bed cover, etc., every day. | Using own produced bio-enzyme to clean rooms and floors. |

| Kitchen | Inorganic and hazardous solid waste management. | Collected by waste collector appointed by local authority. |

| Maintenance | Reducing the use of energy and water. | Use of corrugated plastic roof for maximum use of sunlight and introducing vertical flow of water to avoid pressure of water pump. |

| Food and Beverage | About 60% organic food comes from the mainland of Peninsular Malaysia, which is more expensive than the local price. | Increasing the production of organic garden food via increasing the area of the garden at Frangipani resort. |

| Security | Sea beach erosion along the metal fence around the boundary is expensive. | Planting coconut trees and the morning glory herb along the sea beach to reduce erosion. |

| Accounting | Traditional hospitality practices are losing a big number of tourists from Europe and America who prefer sustainable tourism. | Green practices such as zero-waste concept via composting of organic waste and construction of wetland for greywater treatment have been profitable. |

| Front Office | Access cards were used one time, although now many hotels are using disposable cards. | Less use of paper and envelopes via digitalization of receipts in email. |

| Human Resources | Staff, including the general managers, are from a mono discipline. | Training them to multi-task via involving more than the usual operational activity of Frangipani. |

| Branches | Green Practices | Purposes |

|---|---|---|

| Passive Architecture | Corrugated plastic roof | Maximum natural lighting to enter the room. |

| Green roof and walls | Reduces room temperature to reduce energy consumption of air condition. | |

| Grease trap | Intercept grease and solids from kitchen before entering wastewater system. | |

| Energy and Lighting | Solar energy | Lighting and solar water heaters to provide hot water in bathrooms. |

| Natural lighting and ventilation | Larger windows and open space for more light and air to reduce energy use. | |

| Efficient unit of air condition | Reduce energy consumption. | |

| Electric vehicle | Reduce carbon emission. | |

| Water Conservation | Rainwater harvesting | Landscape and vegetable cultivation, toilet flushing. |

| Water harvesting from air condition | Gardening and irrigation purposes. | |

| Dual flush, low-flow showerhead | Save water consumption. | |

| Organic Farming | Raised bed, hugelkultur, container garden, recycling in nursery | Increasing food production, including vertical vegetation and SRI (system of rice intensification) methods. |

| Black soldier fly larva | Sustainable protein for aquaculture and animal feed. Compost organic waste. | |

| Waste Management | Leaf composting | Fertilizer and retain water longer in soil. |

| Organic composting | Organic fertilizer for the garden. | |

| Eco-enzyme and bio-pesticides | Soil fertilizer, detergent to wash floors, and natural pesticide. | |

| Biodiversity (Flora and Fauna) | Edible, green, flowering, herb plants | Organic vegetables, fruits, and drinks. Use in health care and garden decoration. |

| Organic chicken and duck. | Health protein consumption. | |

| Aquaculture in wetland and pond | Aquaculture in the naturally treated water to produce healthy food. | |

| Wastewater Management and Innovation | Constructed wetland | Biological wastewater treatment for aquaculture and irrigation. |

| Solar dehydrate | Drying is an excellent method of food preservation that maintains a high level of flavor and nutrients in fruits, flowers, and excess food. | |

| Corporate Social Responsibility | Green education | Annual night of nature sustainability camp to promote environmental youth leadership. Environmental knowledge sharing and eco-walk for the visitors. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmed, M.F.; Mokhtar, M.B.; Lim, C.K.; Hooi, A.W.K.; Lee, K.E. Leadership Roles for Sustainable Development: The Case of a Malaysian Green Hotel. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10260. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810260

Ahmed MF, Mokhtar MB, Lim CK, Hooi AWK, Lee KE. Leadership Roles for Sustainable Development: The Case of a Malaysian Green Hotel. Sustainability. 2021; 13(18):10260. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810260

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmed, Minhaz Farid, Mazlin Bin Mokhtar, Chen Kim Lim, Anthony Wong Kim Hooi, and Khai Ern Lee. 2021. "Leadership Roles for Sustainable Development: The Case of a Malaysian Green Hotel" Sustainability 13, no. 18: 10260. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810260

APA StyleAhmed, M. F., Mokhtar, M. B., Lim, C. K., Hooi, A. W. K., & Lee, K. E. (2021). Leadership Roles for Sustainable Development: The Case of a Malaysian Green Hotel. Sustainability, 13(18), 10260. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810260