Toward a Typology of Displacements in the Context of Slow-Onset Environmental Degradation. An Analysis of Hazards, Policies, and Mobility Patterns

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database

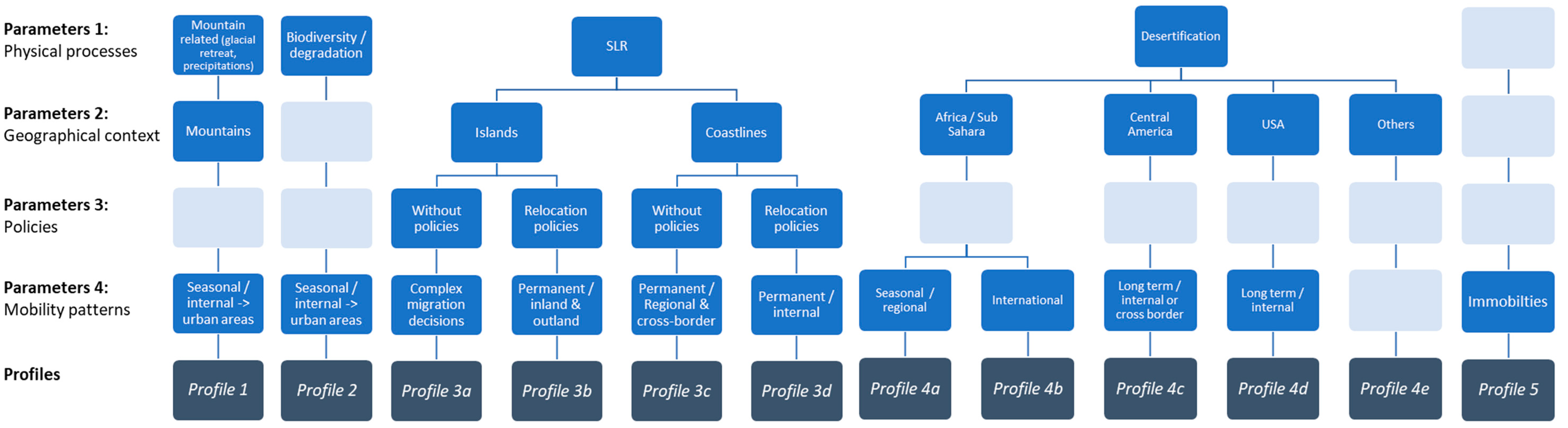

2.2. Parameters

2.2.1. Physical Processes

- Desertification (including droughts and increasing temperatures), episodes of drought are sometimes considered extreme events, but since most studies do not differentiate them clearly from desertification, we decided to include them in this study;

- Sea level rise (SLR), ocean acidification is mentioned in the UNFCC classification, but we did not find any empirical articles documenting this phenomenon in the migration and environment literature;

- Loss of biodiversity and land/forest degradation;

- Glacial retreat.

2.2.2. Geographical Context

2.2.3. Migration-Related Policies

2.2.4. Mobility Patterns

- Distance (local, regional, international, etc.);

- Temporality (temporary, permanent, circular, etc.);

- Motivation (voluntary, forced, multifactorial, etc.);

- Migrants’ characteristics (gender, race, age, education, etc.);

- Other specific situations (statelessness, non-migration, trapped population, etc.).

2.2.5. Excluded Parameters

2.3. Challenges and Limits of Typologies

3. Results: Typology of Displacement

- -

- A brief description of the impact of environmental degradation on migration;

- -

- Mobility patterns—synthesis of the observed migration patterns;

- -

- Policies—description of existing or absent policies;

- -

- Geographic hotspot—list of places where the phenomena is acute;

- -

- Typical example—description of an illustrative case study based on empirical research;

- -

- Documents—number of scientific articles upon which the profile is based;

- -

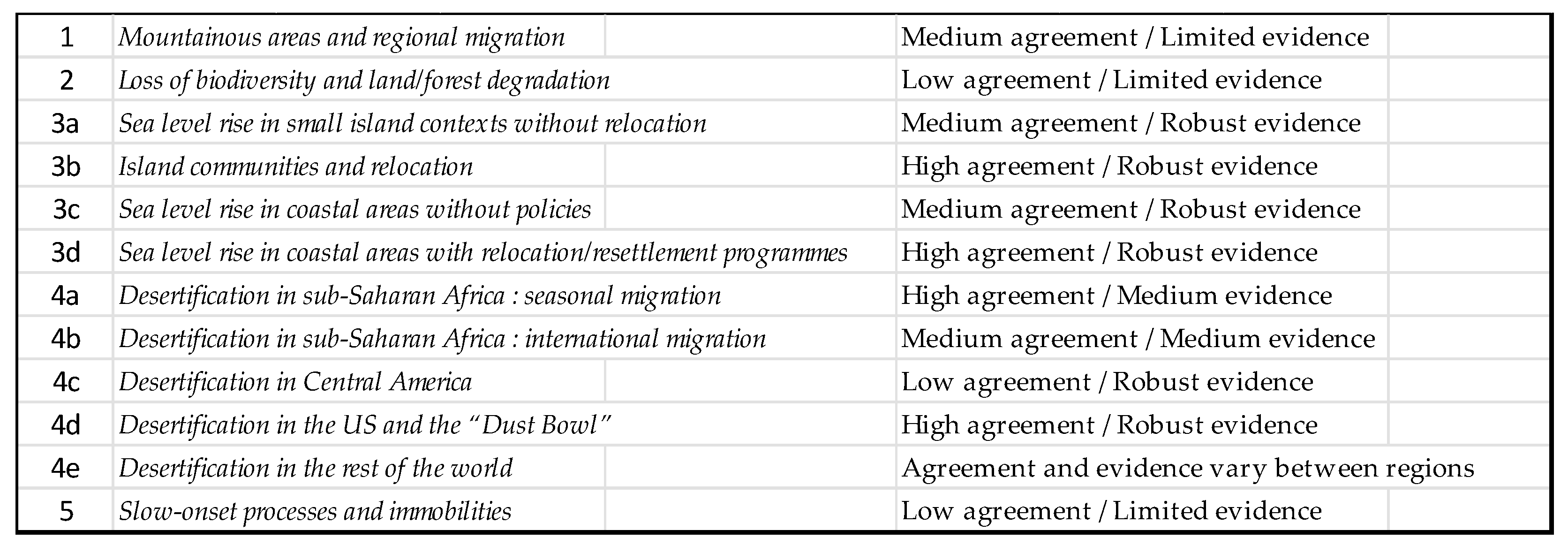

- Confidence—we attempted to qualify each profile with the metrics of the IPCC (https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2017/08/AR5_Uncertainty_Guidance_Note.pdf, accessed on 24 September 2019). We estimated the degree of “agreement” (consensus between researchers/findings with the following qualifiers: High, medium, low) and “evidence” (number and extent of case studies with the following qualifiers: robust, medium, limited). The evaluation of evidence and agreement gives an indication of the level of confidence. If all case studies conclude, for example, that droughts lead to international migration (high agreement), but that these case studies are sparse (limited evidence), the level of confidence remains low. An explanatory note is provided for each qualifier.

3.1. Profile 1: Mountainous Areas and Regional Migration

- Mobility patterns: Migration from mountainous areas is described as mainly internal and oriented towards regional urban centers. Proximity to urban centers often defines the temporality of migration patterns. Those who live close to a city may commute frequently, whereas more remote populations often migrate for longer periods. Non-mobile people—often the elderly and women with children—are particularly vulnerable to climate change in mountainous areas.

- Policies: No specific mentions.

- Geographic hotspot: Andes, Himalayas, mountainous African areas.

- Typical example: Milan et al. (2014) [5] focused on three rural communities in the Central Highlands of Peru, where traditional rain-fed agriculture is the most important economic activity. This article highlights differences in livelihoods and human mobility patterns between households located at different altitudes. In the lowlands, one or more members of most households commute daily to the nearby city. In the highlands, households (or some members) often resettle there. In both cases, circular migration patterns (including daily mobility) can be identified as households combine scarce agricultural income with urban income, rather than abandoning their arable land.

- Documents: Approximately 15 articles.

- Confidence: Medium agreement (very heterogeneous contexts, but similar findings)/limited evidence (studies spread over different areas).

3.2. Profile 2: Loss of Biodiversity and Land/Forest Degradation

- Mobility patterns: Migration patterns are internal. They are often described as temporary or seasonal, generally from rural areas towards urban centers.

- Policies: No specific mentions. Tacoli (2011) [6]—“Policies tend to veer between controlling migrants and ignoring them, with little in between.”

- Geographic hotspot: All the continents are potentially exposed.

- Typical example: Mentioned in the text.

- Documents: Approximately 15 articles.

- Confidence: Low agreement (limited comparison due to heterogeneous contexts)/limited evidence (very few studies).

3.3. Profile 3a: Sea Level Rise in Small Island Contexts without Relocation

- Mobility patterns: Studies of small islands are dominated by qualitative approaches focused on the experiences and perceptions of the population. Researches usually aim to better understand migratory decisions. Studies highlight that even where climate change and environmental degradation have been highly politicized, the key objective of migration in atoll states remains improved access to employment opportunities and affiliated social and economic benefits, such as better housing, health care, and education services. This reveals the complexity of the environment–migration nexus in situations where the impacts of climate change are evident and irreversible.

- Policies: See “Island communities and relocation”.

- Geographic hotspot: Small islands mainly in the Pacific but also Oceania. There is an abundance of case studies on Tuvalu and Kiribati.

- Typical example: Mortreux and Barnett’s (2009) [8] study of Tuvalu shows that most migrants do not cite climate change as a primary reason to leave. People in Funafuti wish to remain where they are for reasons of lifestyle, culture, and identity. Concerns about the impacts of climate change are not currently a significant driver of migration from Funafuti, and do not appear to be a significant influence on those who intend to migrate in the future.

- Documents: Approximately 30 articles.

- Confidence: Medium agreement (complexity of decision-making leading to different behavior)/robust evidence (fair number of studies).

3.4. Profile 3b: Island Communities and Relocation

- Mobility patterns/Policies: The implementation of relocation policies is a characteristic feature of this profile. An extensive body of research exists on involuntary relocation caused by development projects, such as dam construction, mining activities, and natural hazards. Studies have shown that development-induced relocations expose affected communities to risks of impoverishment as a result of losses of livelihood, resources, and civil rights. Many development schemes demonstrate a lack of concern for the social dynamics of displaced communities. Some studies point out interesting measures, such as exchange programs between hosts and resettled communities in order to reduce the risk of conflict. However, relocation is still often described as a strategy of last resort, as any forced move may be maladaptive for those involved, and islanders often resist the idea due to place-based attachment and cultural issues that are of paramount importance.

- Some cases of bilateral migration arrangements at the regional level are described as possible solutions to address statelessness, along with various protective measures, but many authors consider their effective responses inadequate. Exploratory policies such as transnational ex-situ citizenship are also currently being discussed.

- Typical examples (Inland): Charan et al. (2017) [9] explored the interior resettlement of a village in Fiji, underlining obstacles such as disputes over land rights, social cohesion, and emotional and traditional attachments to place. The article’s authors point out that relocation as a climate change adaptation strategy must be considered as a last resort particularly because of the high financial and social costs. Communities differ in levels of vulnerability, and a systematic preliminary assessment should be carried out to determine the most appropriate adaptation strategies.

- Typical examples (Outland): Edwards (2013) [10] examined the relocation of the Carteret Islands, Papua New Guinea. Resettlement had been on the agenda of local government for four decades, and several attempts were made to resettle islanders to Bougainville. All attempts were unsuccessful and resulted in the relocated population returning to the atoll. Findings highlight the issues faced by the displaced community and other stakeholders. Landlessness, unemployment, and support from host communities are key components in the success of resettlement schemes. Replicating island life was only possible on another small island.

- Documents: Approximately 30 articles.

- Confidence: High agreement (good knowledge of relocation issues)/robust evidence (fair number of studies).

3.5. Profile 3c: Sea Level Rise in Coastal Areas without Policies

- Mobility patterns: Migration processes tend to be regional, but cross-border migration is also documented. Mobility varies from temporary to permanent. Increasing environmental risks make planned or unplanned movements unavoidable in the near future.

- Policies: None (profile without policy).

- Typical example: Chen and Mueller (2018) [11] examined the extent to which farmers in coastal Bangladesh can adapt to increased sea/freshwater flooding and soil salinity. The latter is found to have direct effects on internal and international migration patterns. This research suggests that migration is driven, in part, by the adverse consequences of salinity for crop production.

- Geographic hotspots: Bangladesh is by far the most studied area. Other studies focus on Asia (i.e., Indonesia, Vietnam, India). Despite the fact that many coastal areas of China are densely populated, these remain relatively poorly studied in terms of migration. In Africa, studies are mainly located on the western coast, from Mauritania to Nigeria. Egypt is also documented. Latin America is mainly discussed in overviews at the global level, but some case studies document situations in central America (i.e., Belize). Oceania and Europe remain poorly documented.

- Documents: Approximately 70 articles.

- Confidence: Medium agreement (variety of migratory patterns)/robust evidence (significant number of studies).

3.6. Profile 3d: Sea Level Rise in Coastal Areas with Relocation/Resettlement Programs

- Typical examples: Shishmaref, Alaska (US) is widely documented in discussions of relocation measures (i.e., Hamilton et al. 2016) [12]. In this region, relocation is the only strategy that can protect lives and infrastructure. However, the studies point out the ineffectiveness of existing migration and adaptation policies. There is currently no US policy that supports resettling “climate refugees”. The applied policies are a patchwork of various government programs and procedures that are often insufficient. Saint-Louis (Senegal) is designated by UN-Habitat as the African city most threatened by sea level rise (i.e., Zickgraf 2016) [13]. Communities that rely on the fishing industry face dramatic coastal erosion. National authorities have already started to displace the population to inland camps. These camps are precarious and were intended only for temporary use.

- Geographic hotspots: Cf. Profile 3c.

- Documents: Approximately 20 articles.

- Confidence: High agreement (good knowledge of relocation issues)/robust evidence (identified areas are well documented).

3.7. Profile 4a: Desertification in Sub-Saharan Africa: Seasonal Migration

- Mobility patterns: The predominant flows are from rural areas to urban centers, although the literature notes occasional rural-to-rural migration. While young men are over-represented in rural out-migration, there is a growing trend toward a feminization of migration. Lower-educated people are more likely to respond to environmental shock through short-distance migration, whereas highly educated individuals may be candidates for more distant migrations.

- Policies: Few studies document concrete policies. Besides cooperative bilateral projects, a vast international project aims to fight desertification in Sahel and the Horn of Africa. The controversial “great green wall” involves planting a tree wall that crosses 11 countries between Dakar and Djibouti. Its goals are to slow desertification and provide new economic opportunities for climatic resilience.

- While some policy recommendations in the literature address the environment directly, others focus on migration. Mobility is poorly perceived, although migration is an integral part of sub-Saharan African culture. Regarding the environment, recommendations to prevent and reduce the risks related to rainfall deficits are predominant. For example, suggestions include the establishing of small-scale irrigation systems, distributing heat- and drought-resistant crops, and improving access to local weather forecasts in order to prevent trapped populations. In terms of migration, authors underline that it diversifies incomes in semi-arid regions and is therefore a means of adapting to droughts. They suggest that national policies and development policies must take into account this characteristic of Sahelian populations. Finally, as most migration flows towards urban centers, the relevant authorities are encouraged to implement urbanization policies in line with this phenomenon. Moreover, policy proposals need to reconcile economic growth and development goals with pastoralism, agriculture, and climate change adaptation measures.

- Geographic hotspots: Burkina-Faso, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Chad, Benin, Ghana, Nigeria, Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda.

- Typical example: Rademacher-Schulz and al. (2013) [14] examined the interrelationships between rainfall variability, livelihood/food security, and migration in Northern Ghana. This research addresses dry-season migration, and whether this migration pattern is a coping or adaptation mechanism. Using a mixed-methods approach, the results show that a common household strategy is dry-season domestic migration to more suitable farming areas and mining sites.

- Documents: About 70 articles.

- Confidence: High agreement (heterogeneous contexts but general migratory patterns can be distinguished)/medium evidence (high number of studies but great variety of methods and scales of analysis).

3.8. Profile 4b: Desertification in Sub-Saharan Africa: International Migration

- Mobility patterns: Whereas desertification often leads to internal migration, it can also disrupt international migration due to reduced financial resources (poverty trap). Observations show that environmental changes tend to slow out-migration, especially in regions that are highly dependent on natural resources. Nevertheless, environmental changes may influence other migration drivers (i.e., conflicts over natural resources), which in turn may favor international migration.

- Typical example: Henry et al. (2004) [15] suggested that people from the drier regions of Burkina Faso are more likely than those from wetter areas to engage in both temporary and permanent migration to other rural areas. Short-term rainfall deficits also tend to increase the risk of long-term migration to rural areas and decrease the risk of short-term moves to distant destinations. On the other hand, Cai and al. (2016) showed a significant relationship between temperature and international out-migration in agriculture-dependent African countries.

- Policies: As stated in Profile 4a, policies are only marginally taken into account in case studies focused on Africa. Policy recommendations underline the need to develop mechanisms that maximize the benefits of remittances.

- Geographic hotspots: Cf. Profile 4a

- Documents: Approximately 30 articles

- Confidence: Medium agreement (debated results, but tendentially more agreement upon a weak relationship between environmental degradation and international migration)/medium evidence (high number of studies but great variety of methods and scales of analysis).

3.9. Profile 4c: Desertification in Central America

- Mobility patterns: Rural to urban migration within Mexico; international migration from Mexico, Guatemala, Haiti, and other central American countries to the US.

- Typical examples: Nawrotzki, Riosmena and Hunter (2013) [16] found that a decrease in precipitation is significantly associated with US-bound migration, but only for dry Mexican states. However, the same authors showed in another article that declining precipitation relative to the average may reduce emigration in areas undergoing rainfall deficits.

- Policies: Policies are mostly not discussed. Some studies examine programs in the Mexican state of Chiapas where the government has provided financial assistance to residents in order to reduce out-migration.

- Geographic hotspots: Mexico, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and the US (as destination).

- Documents: Approximately 30 articles.

- Confidence: Low agreement (debated results)/robust evidence (well-documented case).

3.10. Profile 4d: Desertification in the US and the “Dust Bowl”

- Mobility patterns: Internal migrations from the Great Plains (Arkansas, Kansas, Oklahoma, North Texas, and parts of Colorado and Missouri) to the western US (Pacific Coast) or from rural to urban areas within the Great Plains.

- Typical example: McLeman and Hunter (2010) [17] used Dust Bowl migration as an interesting analogue to help identify general, causal, temporal, and spatial dimensions of today’s climate migrations.

- Policies: This case offers an interesting historical perspective on policies addressing environmental displacement. Authors note that the governmental policies and programs that have proven most beneficial to drought-stricken farmers were actually designed to stabilize commodity prices, provide income stability for farmers, and create job opportunities for the unemployed. Other federal programs assisted drought migrants. For example, worker camps in southern California were managed by the federal Farm Security Administration in order to provide safe temporary housing for migrants. The authors note that this effort counteracted the attempts of some state and county governments in California to actively discourage migrants and obstruct their access to publicly funded services.

- Geographic hotspot: The Great Plains of the western US.

- Documents: Approximately 10 articles.

- Confidence: High agreement (consistent results)/robust evidence (low amount of research but focused on the same area).

3.11. Profile 4e: Desertification in the Rest of the World

- Austral Africa (6 articles): Some case studies describe how villagers cope with droughts. Support from local leaders and chiefs has been replaced by state support. Long-term migration is no longer popular, with many people preferring to wait for food aid. Other studies give historical perspectives of migratory patterns across this part of the continent.Confidence: Medium agreement (limited findings)/limited evidence (few studies).

- Middle East (6 articles): While climate change is not currently the main driver of migration flows, it does appear to contribute substantially, in that worsening climatic conditions are likely to exacerbate future migration flows. This region is affected by desertification processes, which contribute to migratory systems characterized by rapid and extensive rural–urban migration, established and ongoing cross-border and internal displacement due to war and conflicts, and emigration to neighboring oil-rich countries, as well as Europe, North America, and Australia.Confidence: Low agreement (limited findings)/limited evidence (few studies).

- European countries (4 articles): Although the South of Europe is affected by desertification, few studies underline the migratory impacts, tending to either emphasize the complexities of the relationships between these processes or to observe no relationship at all. Europe is also discussed as a potential destination area. There is a tendency in media discourses to consider that climate change will lead to an increased number of migrants seeking asylum in Europe.Confidence: Low agreement (limited findings)/limited evidence (few studies).

- China (12 articles): Even though a number of articles focus on China, they tend to approach migration through a historical perspective over the last few centuries. The few case studies about the current situation discuss the role of environmental factors in migration decisions, but mobility patterns are poorly documented. Policies are not discussed.Confidence: Low agreement (limited findings)/limited evidence (fair number of studies, but migration is under-documented; political factors).

- South America (24 articles): Desertification processes on this continent are often related to the ENSO oscillations. Droughts in Brazil are particularly well documented and have led to massive decreases in agricultural production and an increase in internal migration, mainly urbanization.Confidence: High agreement (consistent findings)/medium evidence (fair number of studies focused on Brazil, but other areas are poorly documented).

3.12. Profile 5: Slow-Onset Processes and Immobilities

- Policies: Few specific mentions are made. Various studies underline that—especially in the case of relocation—local populations often resist policies that do not take into account their wishes and needs regarding future livelihood conditions.

- Typical examples (Involuntary immobility): Slow-onset events may prevent migration. As rainfall averages increased in the Western Highlands of Guatemala, rural mountain communities suffered from a decrease in local diversification options. Declining out-migration meant fewer remittances, and therefore further local income reductions. These trends expose populations to becoming trapped in places that are extremely vulnerable to climate change. In other regions, droughts or reduced rainfall might reduce migration flows when dwindling resources are allocated to basic needs rather than to out-migration. The remaining receivers of remittances are also immobile populations who may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate variability (i.e., Gray and Wise 2016; Milan and Ruano 2014; Van der Geest 2011). [18,19,20].

- Typical examples (Voluntary immobility): Despite the adverse effects of climate change, in some contexts, people may decide to stay for socio-psychological reasons (i.e., place attachment and place identity concepts). Studies have shown the importance of attachment in an Australian coastal community threatened by sea level rise, and others have shed light on people’s decision to stay in Tuvalu despite growing SLR risks. They are greatly attached to their ancestral lands and wish to adapt in situ (i.e., Adams and Kay 2019; O’Neill and Graham 2016; Mortreux and Barnett 2009) [8,21,22].

- Geographic hotspots: Cases studies documenting these situations are mainly within the contexts of islands and mountainous areas.

- Documents: Approximately 10 articles.

- Confidence: Low agreement (heterogeneous findings)/limited evidence (few studies).

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Slow Onset Events—Technical Paper; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo, C.; Beine, M.; Fröhlich, C.; Kniveton, D.; Martinez-Zarzoso, I.; Mastrorillo, M.; Millock, K.; Piguet, E.; Schraven, B. Human Migration in the Era of Climate Change. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2019, 13, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piguet, E.; Kaenzig, R.; Guélat, J. The uneven geography of research on “environmental migration”. Popul. Environ. 2018, 39, 357–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDMC. No Matter of Choice: Displacement in a Changing Climate—Research Agenda and Call for Partners; Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.internal-displacement.org/publications/no-matter-of-choice-displacement-in-a-changing-climate (accessed on 24 September 2019).

- Milan, A.; Ho, R. Livelihood and migration patterns at different altitudes in the Central Highlands of Peru. Clim. Dev. 2013, 6, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tacoli, C. Not Only Climate Change: Mobility, Vulnerability and Socio-Economic Transformations in Environmentally Fragile Areas of Bolivia, Senegal and Tanzania. IIED Human Settlements Working Paper; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2011; Available online: https://pubs.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/10590IIED.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2019).

- Neumann, K.; Sietz, D.; Hilderink, H.; Janssen, P.; Kok, M.; van Dijk, H. Environmental drivers of human migration in drylands—A spatial picture. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 56, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortreux, C.; Barnett, J. Climate change, migration and adaptation in Funafuti, Tuvalu. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charan, D.; Kaur, M.; Singh, P. Customary Land and Climate Change Induced Relocation—A Case Study of Vunidogoloa Village, Vanua Levu, Fiji. In Climate Change Adaptation in Pacific Countries; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.B. The Logistics of Climate-Induced Resettlement: Lessons from the Carteret Islands, Papua New Guinea. Refug. Surv. Q. 2013, 32, 52–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mueller, V. Coastal climate change, soil salinity and human migration in Bangladesh. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, L.C.; Saito, K.; Loring, P.A.; Lammers, R.B.; Huntington, H.P. Climigration? Population and climate change in Arctic Alaska. Popul. Environ. 2016, 38, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zickgraf, C.; Vigil Diaz Telenti, S.; de Longueville, F.; Ozer, P.; Gemenne, F. The Impact of Vulnerability and Resilience to Environmental Changes on Mobility Patterns in West Africa; World Bankd: Washington DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rademacher-Schulz, C.; Schraven, B.; Mahama, E.S. Time matters: Shifting seasonal migration in Northern Ghana in response to rainfall variability and food insecurity. Clim. Dev. 2014, 6, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henry, S.; Schoumaker, B.; Beauchemin, C. The Impact of Rainfall on the First Out-Migration: A Multi-level Event-History Analysis in Burkina Faso. Popul. Environ. 2003, 25, 423–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrotzki, R.J.; Riosmena, F.; Hunter, L. Do Rainfall Deficits Predict U.S.-Bound Migration from Rural Mexico? Evidence from the Mexican Census. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2013, 32, 129–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McLeman, R.A.; Hunter, L. Migration in the context of vulnerability and adaptation to climate change: Insights from analogues. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2010, 1, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gray, C.; Wise, E. Country-specific effects of climate variability on human migration. Clim. Chang. 2016, 135, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Milan, A.; Ruano, S. Rainfall variability, food insecurity and migration in Cabricán, Guatemala. Clim. Dev. 2013, 6, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Geest, K. North-South Migration in Ghana: What Role for the Environment? Int. Migr. 2011, 49, e69–e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, H.; Kay, S. Migration as a human affair: Integrating individual stress thresholds into quantitative models of climate migration. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 93, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.J.; Graham, S. (En)visioning place-based adaptation to sea-level rise. Geo Geogr. Environ. 2016, 3, e00028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaenzig, R.; Piguet, E. Toward a Typology of Displacements in the Context of Slow-Onset Environmental Degradation. An Analysis of Hazards, Policies, and Mobility Patterns. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10235. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810235

Kaenzig R, Piguet E. Toward a Typology of Displacements in the Context of Slow-Onset Environmental Degradation. An Analysis of Hazards, Policies, and Mobility Patterns. Sustainability. 2021; 13(18):10235. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810235

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaenzig, Raoul, and Etienne Piguet. 2021. "Toward a Typology of Displacements in the Context of Slow-Onset Environmental Degradation. An Analysis of Hazards, Policies, and Mobility Patterns" Sustainability 13, no. 18: 10235. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810235

APA StyleKaenzig, R., & Piguet, E. (2021). Toward a Typology of Displacements in the Context of Slow-Onset Environmental Degradation. An Analysis of Hazards, Policies, and Mobility Patterns. Sustainability, 13(18), 10235. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810235