Island Tourism-Based Sustainable Development at a Crossroads: Facing the Challenges of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

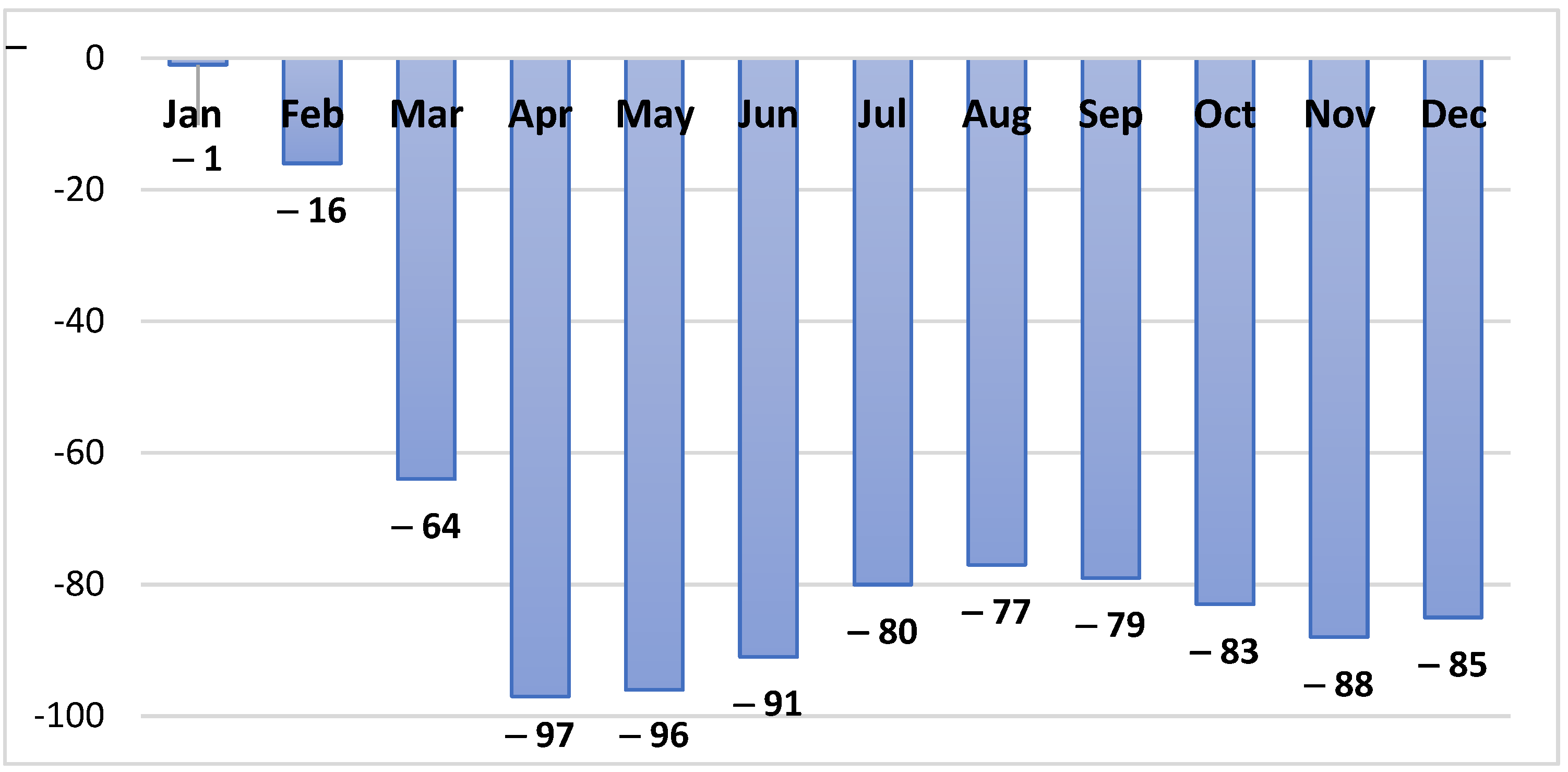

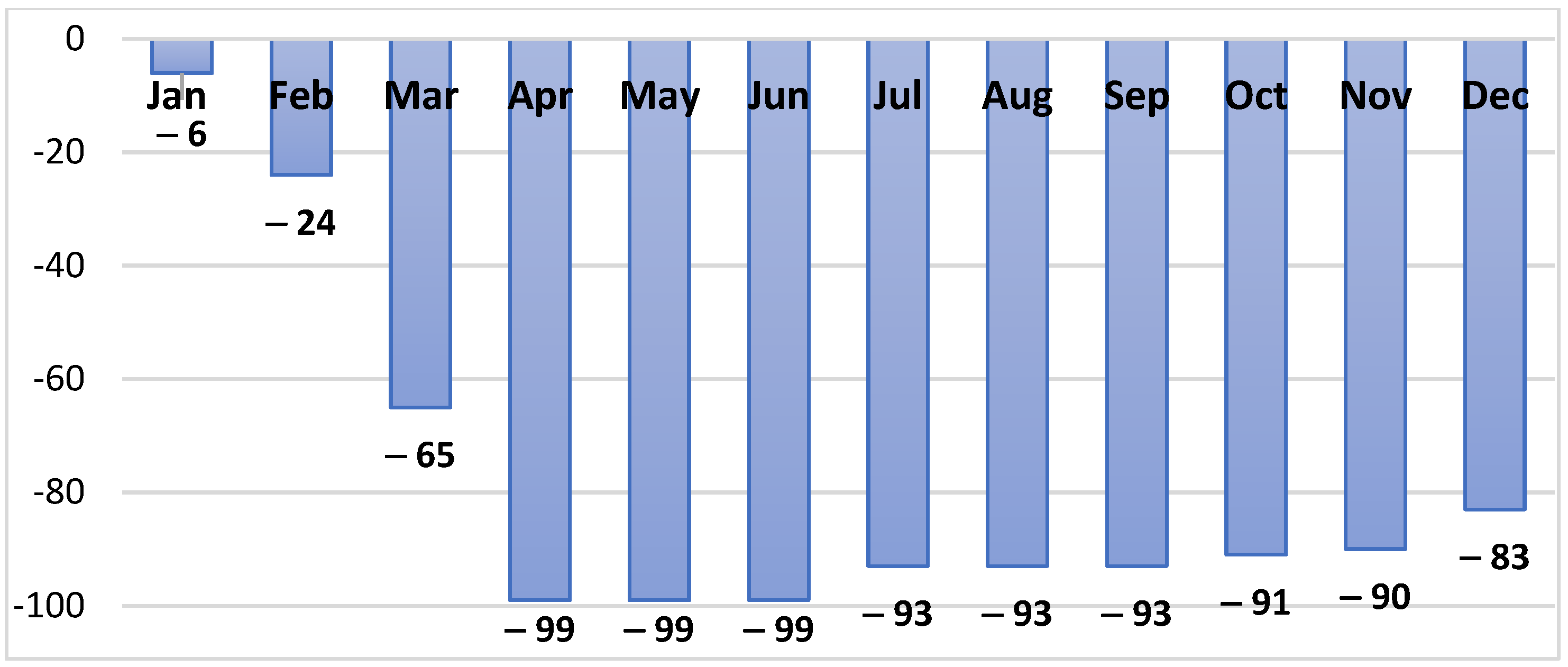

2. Impact of COVID-19 on International Tourism

- 100–120 million direct tourism jobs are at risk; women, who make up 54% of the tourism workforce, youth, and workers in the informal economy are particularly vulnerable;

- International visitors’ spending may have declined by an estimated USD 910 billion to USD 1.2 trillion;

- An estimated 1.5% to 2.8% of global GDP may be lost;

- The economic development and sustainability of many small island development states (SIDS), least developed countries (LDCs), and African nations that rely heavily on tourism may be in danger: tourism represents over 30% of exports for the majority of SIDS and 80% for some of them;

- An estimated USD 5.5 billion in financial assistance would be needed to counteract the adverse effects of the pandemic on SIDS’ economies; and

3. Impact of COVID-19 on Island Tourism

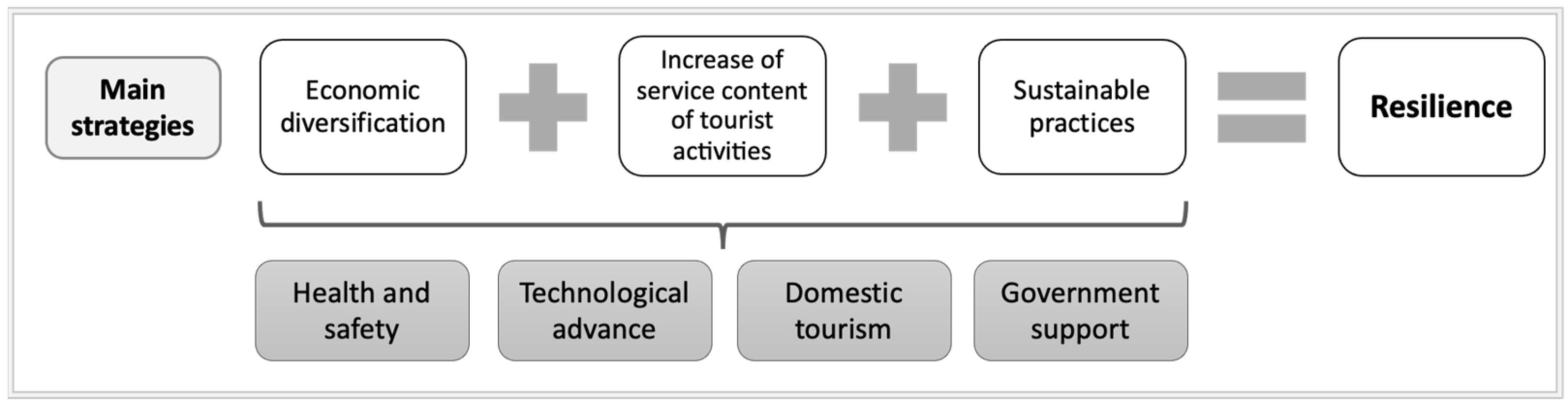

4. Postpandemic Island Tourism Development

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNWTO. The Impact of COVID-19 on Tourism; United Nations World Tourism Organization; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Available online: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2020-08/UN-Tourism-Policy-Brief-Visuals.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Sharpley, R.; Telfer, D. Introduction. In Tourism and Development: Concepts and Issues; Sharpley, R., Telfer, D.J., Eds.; Channel View: Cardiff, UK, 2002; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, R.; Telfer, D. Tourism and Development in the Developing World, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; p. 462. [Google Scholar]

- Cater, E. Environmental contradictions in sustainable tourism. Geogr. J. 1995, 161, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.; Cai, L. Environmental and energy-related challenges to sustainable tourism in the United States and China. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, H.Z. Forms of adjustment: Sociocultural impacts of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1989, 16, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.D. The impacts of tourism on society. Ann. Fac. Econ. Univ. Oradea 2012, 1, 500–506. [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger, Y.; Turner, L.W. Cross-Cultural Behaviour in Tourism: Concepts and Analyses; Butterworth-Heinemann: Hoxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Southgate, C.; Sharpley, R. Tourism, development and the environment. In Tourism and Development: Concepts and Issues; Sharpley, R., Tefler, D.J., Eds.; Channel View: Cardiff, UK, 2015; pp. 250–284. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa, E.; Rotarou, E. Sustainable development or eco-collapse: Lessons for tourism and development from Easter Island. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Armstrong, H.W.; Read, R. The non-sovereign territories: Economic and environmental challenges of sectoral and geographic over-specialisation in tourism and financial services. Eur. Urban. Reg. Stud. 2020, 28, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. The World Bank—Databank: International Tourism. 2021. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ST.INT.RCPT.CD?locations=S2-S3&name_desc=true (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Berno, T.; Bricker, K. Sustainable tourism development: The long road from theory to practice. Int. J. Econ. Dev. 2001, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S. Tourism, economic transition and ecosystem degradation: Interacting processes in a Tanzanian coastal community. Tour Geogr. 2010, 3, 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, P.; Landré, M. The emerging global tourism geography—An environmental sustainability perspective. Sustainability 2011, 4, 42–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rotarou, E.S. Tourism in Zanzibar: Challenges for pro-poor growth. Cad. Virtual Tur. 2014, 14, 250–264. [Google Scholar]

- Theng, S.; Qiong, T.; Tatar, C. Mass tourism vs alternative tourism? Challenges and new positionings. Études Caribéennes 2015, 31–32. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/etudescaribeennes/7708 (accessed on 9 August 2021). [CrossRef]

- Triarchi, E.; Karamanis, K. Alternative tourism development: A theoretical background. World J. Manag. 2017, 3, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benson, A. Research tourism-professional travel for useful discoveries. In Niche Tourism; Novelli, M., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 144–153. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa, E.; Álvarez, R. ITs and ‘Grassroots Tourism’. Protecting native cultures and biodiversity in a global world. In Tourism, Biodiversity and Information; di Castri, F., Balaji, V., Eds.; Backhuys Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 349–380. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. International Tourism Growth Continues to Outpace the Global Economy. Highlights, 2020 ed.; UNWTO: Madrid, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, E.M. UN: Global Tourism Lost $320 Billion in 5 Months from Virus. The Washington Post. 25 August 2020. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/un-global-tourism-lost-320-billion-in-5-months-from-virus/2020/08/25/5a21baae-e693-11ea-bf44-0d31c85838a5_story.html (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Ng, S. COVID-19 and Estimation of Macroeconomic Factors; Working Paper 29060; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ludvigson, C.S.; Ma, S.; Ng, S. Covid-19 and the Macroeconomic Effects of Costly Disasters. NBER Working Paper No. 26987. 2020. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w26987/revisions/w26987.rev0.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- UNCTAD. Impact of Covid-19 on Tourism in Small Island Developing States; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://unctad.org/news/impact-covid-19-tourism-small-island-developing-states (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- UNWTO. International Tourism and COVID-19—Dashboard. 2021. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/international-tourism-and-covid-19 (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- UNWTO. International Tourism Highlights, 2020 Edition; UNWTO: Madrid, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284422456 (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- UNWTO. UNWTO Tourism Recovery Tracker. 2021. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/unwto-tourism-recovery-tracker (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Cruise Lines International Association. 2021: State of the Cruise Industry Outlook. Available online: https://cruising.org/-/media/research-updates/research/2021-state-of-the-cruise-industry_optimized.ashx (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Scheyvens, R.; Momsen, J.H. Tourism and poverty reduction: Issues for small island states. Tour. Geogr. 2008, 10, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, S. The economic impact of tourism in SIDS. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R. Mass tourism has troubled Mallorca for decades. Can it change? In The National Geographic; Travel—Coronavirus Coverage; 2020; Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/mass-tourism-has-troubled-mallorca-spain-for-decades-can-it-change-coronavirus (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- United Nations. Policy Brief: Covid-19 and Transforming Tourism. UN. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_tourism_august_2020.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Independent. Health of tourists and locals at risk on Greek island due to toxic emissions from cruise ships, say environmentalists. Independent: Climate–News. 2018. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/climate-change/news/air-pollution-santorini-greek-island-cruise-ships-nabu-tourism-a8550031.html (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Veiga, C.; Custódio, M.; Águas, P.; Santos, J.A. Sustainability as a key driver to address challenges. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S. Coronavirus: Mallorca Caught in Mass Tourism Trap as Poverty Rises. Deutsche Welle. 2021. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/coronavirus-mallorca-caught-in-mass-tourism-trap-as-poverty-rises/a-56592640 (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Campana, F. How Greece is Rethinking Its Once Bustling Tourism Industry. National Geographic. 2020. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/travel/2020/09/how-greece-is-rethinking-its-once-bustling-tourism-industry (accessed on 23 July 2021).

- Tele13. Rapa Nui-Isla de Pascua se Prepara Para Reapertura con Límite de Turistas y Vuelos. Available online: https://www.t13.cl/noticia/negocios/rapa-nui-isla-pascua-turismo-coronavirus-17-08-2020 (accessed on 8 August 2021).

- UN-OHRLLS. Small Island Development States—Small Islands Big(Ger) Stakes; UN-OHRLLS: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Available online: http://unohrlls.org/custom-content/uploads/2013/08/SIDS-Small-Islands-Bigger-Stakes.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Neufeld, D. Visualizing the Countries Most Reliant on Tourism. Visual Capitalist. 2020. Available online: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/countries-reliant-tourism/ (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Mulder, N. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Tourism Sector in Latin America and the Caribbean, and Options for a Sustainable and Resilient Recovery (Coord.); International Trade Series, No. 157 (LC/TS.2020/147); Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean: Santiago, Chile, 2020; Available online: https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/publication/files/46502/S2000751_en.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- World Bank. New Surveys Track the Economic and Social Impact of COVID-19 on Families in Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands. Press Release. 2020. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/12/08/new-surveys-track-the-economic-and-social-impact-of-covid-19-on-families-in-papua-new-guinea-and-solomon-islands (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- McGarry, D.; Chanel, S.; Samoglou, E. Deserted Islands: Pacific Resorts Struggle to Survive a Year without Tourists. The Guardian. 2021. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/apr/03/covid-coronavirus-deserted-islands-pacific-resorts-struggle-to-survive-a-year-without-tourists (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- McGarry, D. Vanuatu Coronavirus Vaccine Rollout to Take until End of 2023. The Guardian. Global Development. 2021. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/feb/26/vanuatu-coronavirus-vaccine-rollout-to-take-until-end-of-2023 (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Tsai, M.-C. Developing a sustainability strategy for Taiwan’s tourism industry after the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, F.; Filho, W.L.; Singh, P.; Scherle, N.; Reiser, D.; Telesford, J.; Miljković, I.B.; Havea, P.H.; Li, C.; Surroop, D.; et al. Influences of climate change on tourism development in Small Pacific Island States. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjeev, G.M.; Tiwari, S. Responding to the coronavirus pandemic: Emerging issues and challenges for Indian hospitality and tourism businesses. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiza, T.; Slabbert, E. Tourism is too dangerous! Perceived risk and the subjective safety of tourism activity in the era of Covid-19. Geoj. Tour 2021, 36, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.R.; DiPietro, R.B. Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the perceptions and sentiments of tourism employees: Evidence from a small island tourism economy in the Caribbean. Int. Hosp. Rev 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, G.; Castanho, R.A.; Pimentel, P.; Carvalho, C.; Sousa, A.; Santos, C. The impacts of COVID-19 crisis over the tourism expectations of the Azores Archipelago residents. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Fusté-Forné, F. Post-pandemic recovery: A case of domestic tourism in Akaroa (South Island, New Zealand). World 2021, 2, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babii, A.; Nadeem, S. Tourism in a Post-Pandemic World. IMF Country Focus 2021. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2021/02/24/na022521-how-to-save-travel-and-tourism-in-a-post-pandemic-world (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Caon, V. Can Caribbean Economies Diversify from Beaches to BPO? Investment Monitor. 2021. Available online: https://investmentmonitor.ai/tourism/can-caribbean-economies-diversify-from-beaches-to-bpo (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- OECD. Rebuilding Tourism for the Future: COVID-19 Policy Responses and Recovery; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=137_137392-qsvjt75vnh&title=Rebuilding-tourism-for-the-future-COVID-19-policy-response-and-recovery (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Bloomberg. Bali to Impose $10 Tax on Foreign Tourists. Jakarta Post Reports. 2019. Available online: https://www.bloombergquint.com/onweb/bali-to-impose-10-tax-on-foreign-tourists-jakarta-post-reports (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- TravelWeekly. Ecuador to limit number of visitors to Galapagos Islands. TravelWeekly—News. 2011. Available online: https://travelweekly.co.uk/articles/38786/ecuador-to-limit-number-of-visitors-to-galapagos-islands (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Kathimerini. The ‘Covid-free’ islands of Greece: Hope for tourism. Kathimerini. 2021. Available online: https://www.kathimerini.gr/economy/561295051/kastellorizo-o-protos-covid-free-proorismos-stin-ellada/ (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Khosravani, V.; Ardestani, S.M.S.; Bastan, F.S.; McKay, D.; Asmundson, J.G.J. The associations of obsessive–compulsive symptom dimensions and general severity with suicidal ideation in patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder: The role of specific stress responses to COVID-19. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. COVID stress syndrome: Clinical and nosological considerations. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2021, 23, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, A. COVID’s Mental-Health Toll: How Scientists Are Tracking a Surge in Depression. Nature 2021, 590, 194–195. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00175-z (accessed on 19 July 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behsudi, A. Wish You Were Here. International Monetary Fund—Finance & Development. 2020. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/12/impact-of-the-pandemic-on-tourism-behsudi.htm (accessed on 9 July 2021).

- IPCC. Summary for policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press, 2021; in press; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Full_Report.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Moreno-Luna, L.; Robina-Ramírez, R.; Sánchez, M.S.; Castro-Serrano, J. Tourism and sustainability in times of COVID-19: The case of Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, S.; Madgavkar, A.; Manyika, J.; Smit, S. What’s Next for Remote Work: An Analysis of 2.000 Tasks, 800 Jobs, and Nine Countries. McKinsey Global Institute. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/whats-next-for-remote-work-an-analysis-of-2000-tasks-800-jobs-and-nine-countries (accessed on 8 August 2021).

- Malhotra, M. Paradigm shift in the global hospitality industry-Impact of pandemic Covid-19. IJRTBT 2021, 5, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S. Covid-19: A Paradigm Shift for the Hospitality Industry. The Economic Times. 2020. Available online: https://hospitality.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/speaking-heads/covid-19-a-paradigm-shift-for-the-hospitality-industry/76168281 (accessed on 23 July 2021).

- Tozee, N. The Normal Economy Is Never Coming Back. Foreign Policy. 2020. Available online: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/15/how-the-economy-will-look-after-the-coronavirus-pandemic/ (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Posen, A. The Economy’s Preexisting Conditions Are Made Worse by the Pandemic. Foreign Policy. 15 April 2020. Available online: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/15/how-the-economy-will-look-after-the-coronavirus-pandemic/ (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Gopinath, G. The Great Lockdown: Worst Economic Downturn since the Great Depression. IMF Blog. Available online: https://blogs.imf.org/2020/04/14/the-great-lockdown-worst-economic-downturn-since-the-great-depression/ (accessed on 8 August 2021).

- Digital Agency Network. Crowd Says the British Staycation Could Be Here to Stay. Available online: https://digitalagencynetwork.com/crowd-says-the-british-staycation-could-be-here-to-stay/ (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Destination Analysts. Update on American Travel Trends and Sentiment—Week of 12 July 2021. Available online: https://www.destinationanalysts.com/insights-updates/ (accessed on 29 July 2021).

- Josephs, L. It’s Not Your Imagination. Rising Airfares and Hotel Rates Are Making Vacations More Expensive. CNBC, Transport. 2021. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2021/05/23/covid-travel-rising-airfares-and-hotel-rates-are-making-vacations-more-expensive.html (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Sampson, H. Travel Was Cheap when No One Was Traveling. That Era Is Over. The Washington Post. 2021. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/travel/2021/07/01/summer-cheap-flights-europe-us/ (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- UK Department of Transport. Red, Amber and Green List Rules for Entering England. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/red-amber-and-green-list-rules-for-entering-england#amber-list (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Tsai, T.; Chen, C. Evaluating tourists’ preferences for attributes of thematic itineraries: Holy folklore statue in Kinmen. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, E.N. EU Pledges Help, as Tourism Faces €400bn Hit. EU Observer. 2020. Available online: https://euobserver.com/coronavirus/148137 (accessed on 12 August 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Figueroa B., E.; Rotarou, E.S. Island Tourism-Based Sustainable Development at a Crossroads: Facing the Challenges of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10081. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810081

Figueroa B. E, Rotarou ES. Island Tourism-Based Sustainable Development at a Crossroads: Facing the Challenges of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2021; 13(18):10081. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810081

Chicago/Turabian StyleFigueroa B., Eugenio, and Elena S. Rotarou. 2021. "Island Tourism-Based Sustainable Development at a Crossroads: Facing the Challenges of the COVID-19 Pandemic" Sustainability 13, no. 18: 10081. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810081

APA StyleFigueroa B., E., & Rotarou, E. S. (2021). Island Tourism-Based Sustainable Development at a Crossroads: Facing the Challenges of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 13(18), 10081. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810081