Abstract

Today, communal urban gardening (CUG) is a widespread phenomenon in European cities. Gardening has many positive qualities, ranging from growing healthy food to meaningful everyday life activities and political action. However, its integration into existing urban planning processes remains a challenge. Planning has a great influence on the qualities that can actually be realized by the gardeners. In order to develop a more appropriate planning process for CUG, a deeper understanding of the different activities that people engage in when they are gardening in an urban environment under given conditions is needed. In this paper, a garden project from Vienna is discussed against the background of Arendt’s theory of political action to advance the theoretical debates on the planning of CUGs. The case study shows that the three central spaces of a vita activa can emerge in one place if the appropriate framework conditions are provided through planning: containment, sovereign rights of use, egalitarian participation, plurality, and spatial organization towards the three activities of a vita activa: labor, work, and action.

1. Introduction

Community gardening has repeatedly contributed to solving urgent problems in the past. Allotment gardens counteracted the health effects of industrialization, victory gardens secured food supplies [1], and community gardening reduced neighborhood neglect [2] and improved children’s health [3]. Current forms of Communal Urban Gardening CUG [4] are seen as a promising solution to various problems such as the climate crisis [5] or the political crisis [6,7] on a local level. At the same time, CUG is itself a problem for late modern urban planning [8]. Politics and administration still find it difficult when city dwellers become active in a self-determined way and take joint responsibility for a piece of land in the city [6]).

The rise of modern society included the rise of management elites, promising to lead mass society into lasting progress [9]. This also applies to modern, technocratic-bureaucratic urban planning. In Vienna, the corporatist model with a strong bureaucracy worked satisfactorily for a long time. Social problems were cushioned as far as possible by the welfare state [10]. Individual initiative was neither necessary nor desirable, being more of a threat to established processes. In the 21st century, this apolitical mentality [11] (Straßenberger, 2015) meets the disintegration of welfare-state structures through neoliberal dynamics [12].

The elites and their technocratic governance have failed and today face a public frustrated by disempowerment, moving from resistance to destruction [9]. We are witnessing a crisis of liberal democracy and revolts against governments run by elites with a rapid decline of the political categories on which the modern era was founded [13]. Even in the 1960s, Hannah Arendt described this phenomenon as a momentous double process of Weltentfremdung (world alienation) in modern mass society [14]. It is an alienation of political elites and citizens from political responsibility [11]. Arendt’s analysis of Weltentfremdung as the dissolution of all binding and connecting relational structures has proved astonishingly current (Berkowitz, 2020). She pleads—especially in times of crisis—for keeping space open for political action and promoting the necessary (re-)politicization.

Since communal urban gardening (CUG) has unfolded its diverse, including political, potential especially in times of crisis, I explore here the extent to which CUG supports a vita activa and can, therefore, also be a space for political action in the Arendtian sense, the spatiality associated with it and the extent to which Arendt’s political theory of action can support spatial theories and planning concepts like Innenhaus and Außenhaus, which is used in German-speaking countries. Her conceptual theoretical thinking promises to advance the theoretical debates on planning autonomous appropriations of space by CUG, for example, and a new understanding of urban gardening as political gardening [6].

The article is based on a case study (2008–2019) on a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context [15,16], with a social-constructivist approach using mainly sources of qualitative evidence [17,18]. I conducted all the empirical work myself, using a mix of methods including (1) participant observation (two times a year between 2010 and 2019), (2) field mapping (2018), (3) semi-structured interviews in German (2018), (4) a written questionnaire in German and Turkish (2018), and (5) a group interview in Turkish with German translation (2018).

The garden is located in a typical 1960s modern functionalist municipal housing estate in Vienna [19]. There, as part of an expert-led, three-year pilot project, a self-organized community garden was created in a participatory planning process [20] by a group of neighbors who hardly knew each other.

A practical application of Arendt’s theory to planning is new and seems a risky enterprise [11], not only because Arendt’s thinking is at odds with the major schools of thought [21], but also because the practicality of Arendt’s theory and her demand for the exclusion from politics of the social question have often been criticized [22]. Nevertheless, I will venture to make Arendt’s theory of vita activa accessible to a specific planning concept by applying her distinctions of phenomena and concepts to a real example. Encouragingly, Arendt does not tell us what to think or do, but gives an example of how we might think, given the conditions of our world [21]. Thinking with Arendt means first of all to go at a distance to the known concepts of landscape planning and to follow Arendt’s peculiar ideas of spatiality. I attempted to understand the theoretical and practical significance of distinction, boundaries, and the various spaces of meaning and action that are performatively generated, actively shaped, and permanently reproduced. In a next step, I turned to a specific landscape planning concept to test its compatibility with Arendt’s theory and to expand the concept. I refer in this paper mainly to Arendt’s German-language works [14,23,24,25,26], to interpretations of Arendt’s spatial thinking by Debarbieux [27], of Arendt’s public and social space by Benhabib [28,29], and of Arendt’s political thinking by Straßenberger [11] and Cavarero [13].

Taking the case study as a basis, I will show that all three primary activities in the sense of a vita activa (labor, work, and action) take place in communal urban gardening. A private and a public sphere can, therefore, emerge in the midst of the social sphere of functionalist multi-story housing, changing people’s everyday lives and their settlement. I will show that three different spatialities can be defined from a planning perspective: (1) a subsistence-productive space to sustain life itself through labor, (2) a (co-)creative space in which a shared world is created through work, and (3) a co-present space from which a public sphere can appear between people involved through speaking and acting.

The three spatial ontologies identified in CUG are interconnected and build on each other. CUG, by eluding formal approaches to planning, makes us realize that the spaces of a vita activa cannot be planned in terms of work (poiesis). Public space, as contextual, contingent, and pluralistically constituted space [13], can only be created in a combination of poiesis and praxis. What planning can do is create specific framework conditions so that the three activities are available as potentials. When adapting the pre-modern, feminist planning concept of Innenhaus and Außenhaus [30] for community gardening in modern multi-story housing developments, the following framework conditions for the three activities of a vita activa can be named: containment, ownership (in the sense of sovereign right of use), a spatial and socio-economic organization oriented towards all three activities, egalitarian participation, and plurality. The spatiality of a vita activa, gives political gardening an additional significance relevant to planning theory as everyday political action, which can easily be overlooked.

2. Labor, Work and Action: Organizing Private and Public Spaces

In “The human condition” [31], Hannah Arendt explores the question “What do we actually do when we are active?” [14]. She makes a phenomenological distinction between three basic activities (labor, work, and action), in each of which three basic conditions of human life (life itself, worldliness, and plurality) take place [14,32]. With the term vita activa, the title of the German version translated and expanded by Arendt herself [31], she takes up the Greek concept of the active, political life (bio politikos) and highlights the differences levelled by Christian doctrines [14].

Arendt links labor and consumption with the compelling necessities of life, mere survival and biological reproduction, as reflected in the infinite circles of recurring biological processes. Labor produces only short-lived products (consumer goods) and labor itself. With work, man fabricates representational objects, Weltdinge, that are used but not consumed. Work is sovereign, purposeful, with an end–means relationship (2018b: 182), and according to a model that remains after the process [14]. The summation of all things fabricated adds up to a world built by humans [29], which stabilizes human life. Labor and work can be carried out alone and, according to Arendt, are both private and fundamentally apolitical (2018b: 192). Only speaking and acting are free from the conditionality of life and worldliness. They constitute the field of politics and history and make a life human in the first place (Arendt, 2018b: 215). The purpose of action is the doing (praxis) itself [11,14]. Politics arises in relations and relationships between people, where they intersubjectively consider the same topic from different perspectives with an open-minded attitude (plurality) and form their own opinion. Then, speaking is not “mere talk”, but a sense of reality emerges [11,14]. For Arendt, the core of the political is debate and concern for a common world that we can share even in the face of fundamental dissent [32]. In her non-denominationist conception of politics [11,14], the focus is on the everyday, on being in the world. For Arendt, the “social question” cannot be solved by political means [24]; it belongs to the sphere of the Social and is the task of administration [21].

In her work vita activa [14], Arendt pays much attention to how places and spaces are shaped according to the requirements of the particular kind of human activity [14,27]. There is dependency between the private and the public sphere [14] and they are in tension [29]. In modern times, the Social is added to this strict binary opposition as a phenomenon of mass society [14]. It is not a sphere of its own, but denotes the lack or absence of political action [33], when human issues are treated as natural necessities and action is replaced by rules and behavior. The personal, as opposed to the private, is not at all a private matter in a public space [14,34] and feminist interpretations point out that the Social can be politicized when the human issues behind the rules are seen as negotiable and changeable [33] and the types of action are questioned from the standpoint of asymmetrical power relations [28]. Then the dividing line between private and public is renegotiated [29] and the personal becomes objectively ascertainable [34].

The private realm, derived from the Greek oikos, serves to protect the private sphere from the public sphere [11,14] and is the pre-political realm of economic necessities, characterized by domination and violence. Referring to Woolf [35], Benhabib sees the home as privacy in the most significant sense, offering space that protects and nurtures, making the individual fit to appear in public [29]. Arendt’s concept of privacy, as opposed to intimacy [14], is shared by feminist theories that distinguish between a home and a specific structure, such as the monogamous, patriarchal nuclear family (homeless at home) [29]. CUG can be a key site of home making [36] or ‘paradoxical spaces’ allowing simultaneous occupation of dualist categories as ‘privatepublics’ [37].

The public realm, the space of political action [14], is not a topographical space [29]; it is a relational space, contextual, contingent, and pluralistically constituted [11]. It opens everywhere for everyone [13]. It is constituted as liberation from physical constraints in the place where everyday life takes place [38]. It is limited, the boundaries having to be politically generated according to the logic of action and not naturally or ontologically determined [39]. The prerequisite for this political-public space is that it remains free of economic logic and necessity [33]. This space of genuinely political experience of “acting in concert” in a “space of appearance” is like a stage where human beings experience themselves as unique beings and show “who” they are (Ipseity) performatively [11]. This performative approach guides Arendt in her search for the fortunes of history in which politics is not understood as domination and obedience [34], in order to develop interpretative categories that counteract totalitarian tendencies and to re-imagine a pluralistic politics without liberal and individualistic ideals [9].

Arendt’s trilogy of basic human activities and the conditions of collective existence of individuals (Ipseity and Plurality) serves an understanding of the empirical foundations of the human condition. Debarbieux [27] shows how she combines and differentiates three spatial ontologies in a hierarchical way, without directly correlating them with Arendt’s typology of human activities. In the first, ‘natural’ space, things and beings take place in a biophysical environment (taking place). In a phenomenal space, things appear before people. Here each individual constructs his or her own position in relation to positions, and here many individuals accordingly form common worlds (having a position). In a praxeological space, politics develops in an in-between space as a relationship between people in co-presence (having a stand). He notes that Arendt’s work invites us to overcome modern notions of spatiality and focus on plurality and the need for a corresponding public space [27].

For Arendt, human affairs and activities each belong to separate spheres, the private or the public [27]. Planners formulate these borderlines between the private and the public through built structures, thereby enabling or preventing activities. Parallel to the rise of the Social, in modernity the built form has lost its mediating capacity to distinguish private from public [40]. Preserving this difference is a central aspect of the planning approach that was applied in the case study and tested for its relevance to a vita activa.

3. Vita Activa in the Innenhaus and Außenhaus Planning Concept

Inge Meta Hülbusch developed the concept of Innenhaus and Außenhaus [30] as early as the 1970s and, thereby, had considerable influence on critical and feminist open-space planning in the German-speaking countries. The conceptual pair of Innenhaus and Außenhaus refers to the productive connection between inside and outside [41] within the ‘whole house’ [42], the pre-modern economic unit and (re)production site of the family. Instead of the aesthetic design of residential landscapes, Hülbusch focuses on everyday life. She formulates the spatial and socio-economic framework conditions as basic planning principles for the production of open spaces during everyday use: immediate proximity to the house (flat), direct relationship between indoors and outdoors, clear distinction between private and public, focus on organization and zoning according to everyday activities (housework, care duties, handicrafts), complete workplaces for domestic (re)production, focus on utility value, personal scope for decision making and self-determined use of resources. Through multiplication, parcels that allow for an Innenhaus and Außenhaus result in a productive and frugal settlement organization, which promotes individual initiative, personal responsibility, and local community [43]. The effort for public administration remains manageably limited to streets and squares. Since a free choice of residence does not exist for all people, Hülbusch sees the responsibility of open space planning in securing the potential for an indoor and outdoor home [30]. Here, ‘public’ space is not understood as political-public space, but as the social sphere of administration.

Hülbusch herself did not refer to Arendt’s work, although there are obvious similarities on a pre-political level: the phenomenological perspective, the clear distinction between private and public, the archetype of the oikos as a place of domestic economy and production, the concept of being ‘dwelt in’ [40], the preference for being active rather than administering, and the critique of the primacy of the modern economy and commodity logic with regard to land. In their dissertations, Kurowski [44] and Kölzer [45] have established a link between the private aspects in Hülbusch’s concept of space and Arendt’s vita activa, in a notion of feminist subsistence perspective [46]. I will elaborate on this connection and show how the pre-political concept can be expanded to include the dimension of political action.

4. The Roda-Roda Garden

CUG has existed in Vienna for a very long time, in different organizational forms and intensities. While thousands of traditional allotment gardens have been converted into building sites since the 1980s, 90 new community gardens have been created since 2010 [47]. About two-thirds of these are municipality-influenced gardens on public land [48], managed by municipality-based organizations for 1–2 years and remaining supervised. The municipal administration, based on a corporatist model with a strong bureaucracy, has in this way reacted to the increasing demands of the UG and can keep activities under control.

The case study is a municipally funded pilot project (2009–2011) in Viennese social housing. It was initiated and guided for three years by an interdisciplinary, all-women project team, including the author. The specifications from the funding bodies were inclusivity, involvement of the democratically elected representation of the 1500 tenants, and the fencing of the garden. The aim was a fully self-governed garden community in 2011 for diverse, less-privileged groups and especially women with intensive care duties. It was also intended to create spaces for meeting and support in everyday life, to counteract growing everyday racism by building personal relationships, and to revitalize self-governance in social housing.

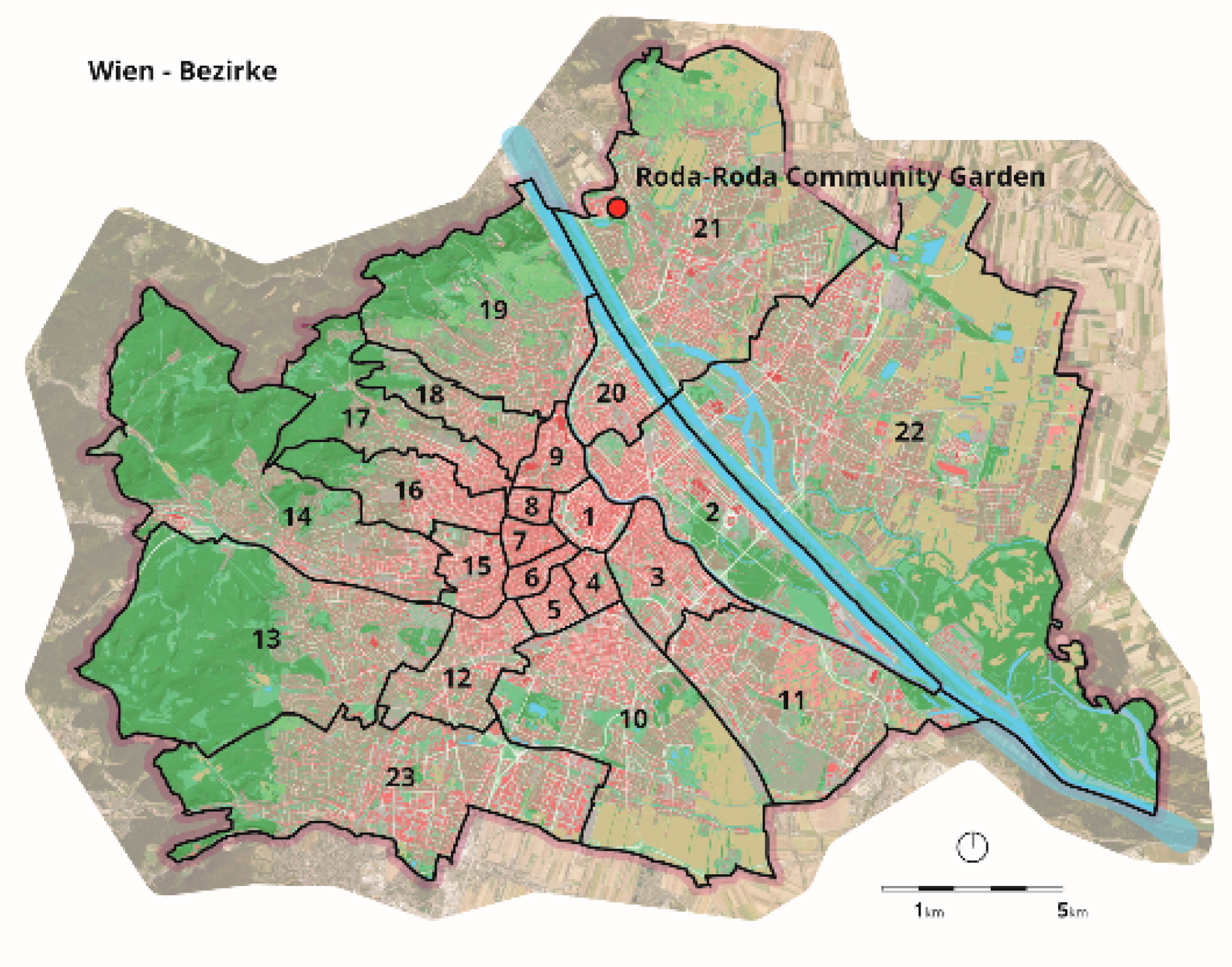

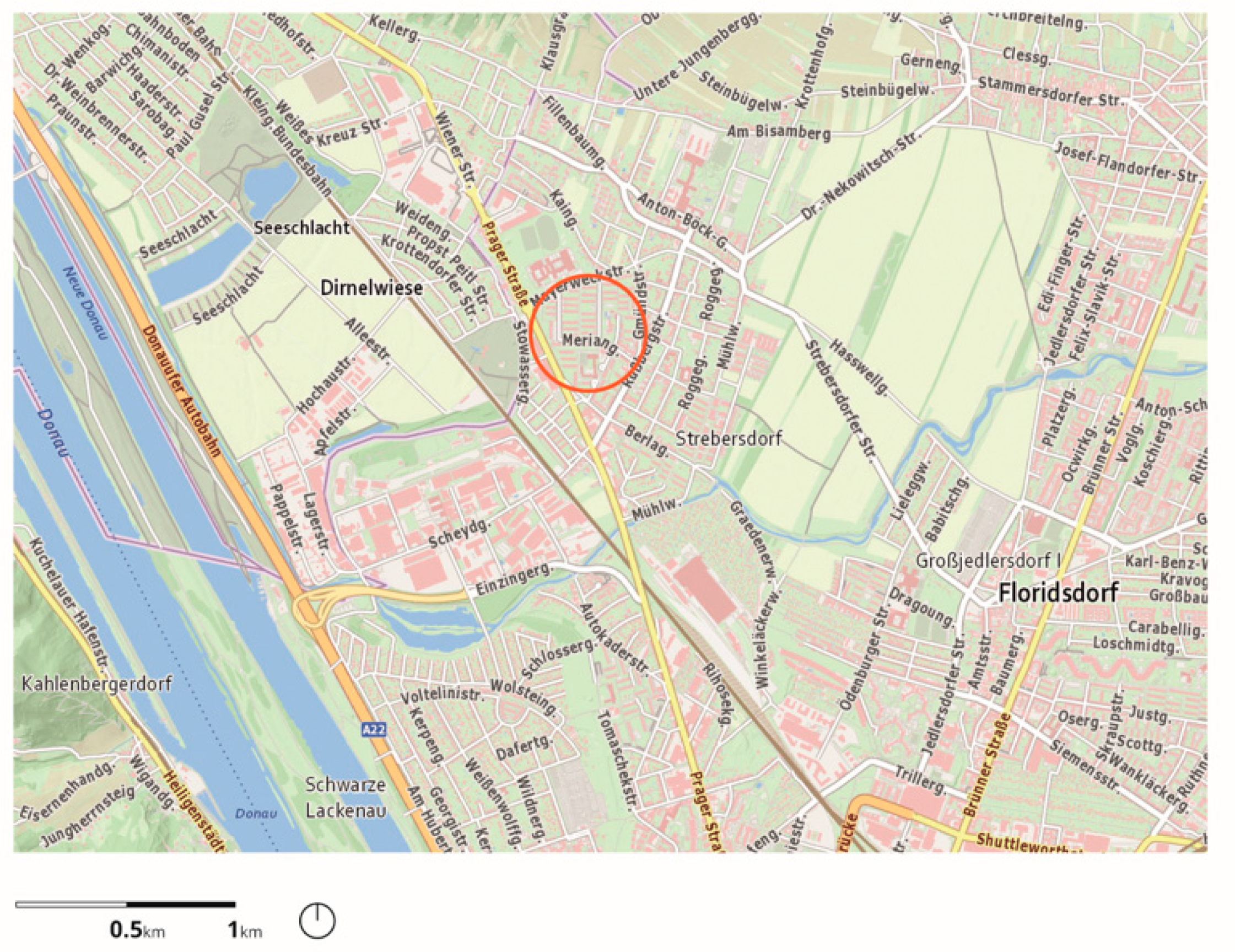

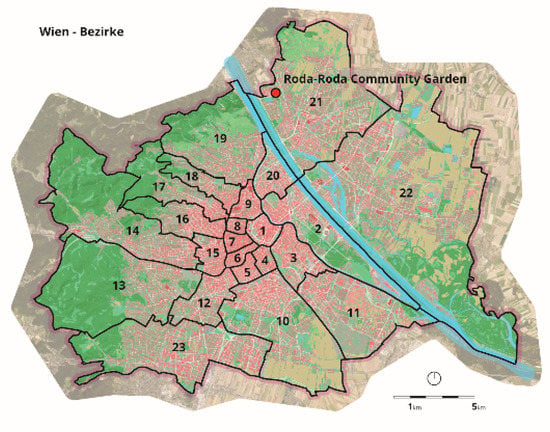

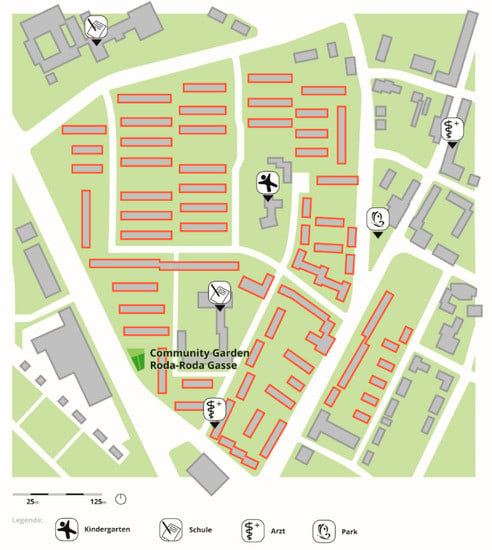

The Roda-Roda Garden, named after a street nearby, is located in a 1960s housing estate in the north of Vienna, where about 1500 people live in rows of 2–4 story houses. They are surrounded by extensive, barely used green spaces, a modern version of a landscaped park with large trees, groups of shrubs, and extensive meadows (see Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 1.

The map shows the location of the garden in the urban area of Vienna. (Author’s own illustration based on Stadt Wien-ViennaGIS).

Figure 2.

The map shows the location of the garden in detail. (Stadt Wien-ViennaGIS).

Figure 3.

The map shows the garden surrounded by 2–4-story row houses and the basic infrastructure. (Author’s own illustration based on Stadt Wien-ViennaGIS).

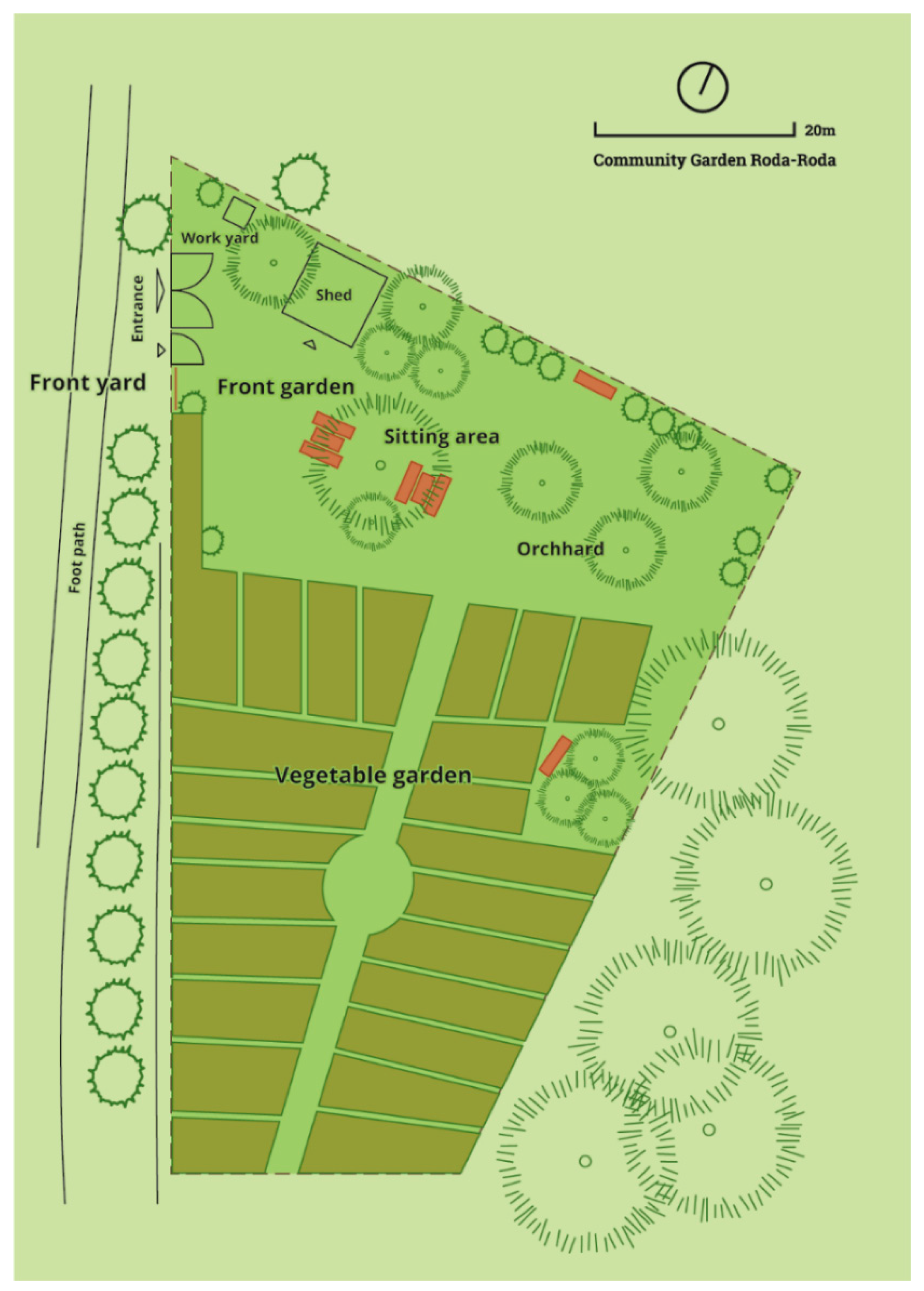

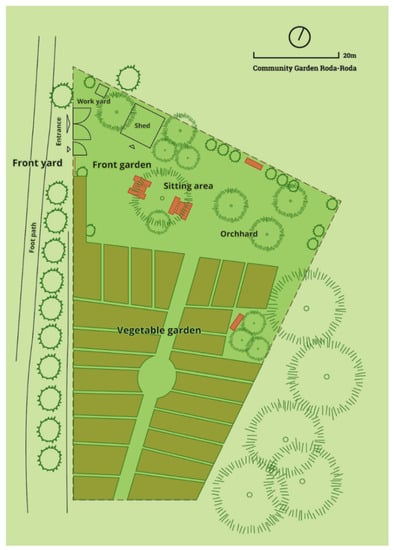

The garden is 800 m2, of which 300 m2 is communal area (area A) and 500 m2 is divided into 24 individually cultivated vegetable beds (area B) each about 10 m2 (Figure 4 and Figure 5). The flats are between two and five minutes’ walk away. The garden is surrounded by a 1.20-m fence and is only accessible to the public on certain days.

Figure 4.

The picture on the shows Roda-Roda-Garden with view from the vegetable garden to the communal area (author’s own photograph).

Figure 5.

The picture shows the vegetable garden (author’s own photograph).

The gardeners (individuals, couples, and families) are organized into an association with a usage contract with the owner (Wiener Wohnen). In 2020, the association had a total of 30 members, 20 women and 10 men aged between 30 and 80, speaking German, Turkish, Filipino, Bosnian, and Arabic (ranked by frequency). Eleven of them were founding members in 2009. All gardeners live in the close neighborhood. They did not know each other before and represent the diversity of the estate. The garden has been autonomous and self-organized since 2010. It has become an inseparable part of life for many of the gardeners. The beds are usually only passed on when life circumstances force this (illness, death, new job). Since 2011, there have been 34 additional individual appropriations for gardening on the housing estate (as of 2019)

Based on the traditional house garden concept, it is divided into several different areas according to use: front yard, front garden, work yard with shed, orchard, and seating area and vegetable garden with individual beds (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Zoning and patterns (author’s own illustration).

5. Vita Activa in the Roda-Roda Garden

In this study, the three basic activities of labor, work, and action serve as analytical categories to distinguish the activities in the garden and to describe their specific spatial qualities. The aim was not to make a clear-cut classification, but to understand what the gardeners are actually doing when they are active [14].

5.1. Gardening as Labor

Many activities that take place in the garden bear the characteristics of labor. They are routine, repetitive, vital for the human organism, and they are consuming processes with no enduring results (worldlessness). Weeding, mowing, mulching, or pest control are necessary for cultivation (Figure 7). They move in recurring natural cycles and are never quite finished. The results—tomatoes, beans, or vine leaves—are short-lived products. Being consumed is part of their nature.

Figure 7.

The picture shows a gardener digging on his plot in Roda-Roda-Garden (author’s own photograph).

Other activities that can also be observed are for health and life support, such as sitting in the sun, socializing, daily routine, regular and moderate physical activity, contentment, contact with the soil, experiencing the weather, or working in rhythm with nature and one’s own body. Gardeners can spend time there alone or in groups. While single people appreciate the garden as a place of communication, it serves more as a retreat for gardeners with large families.

The beds in the case study are too small for self-sufficiency cultivations. Primarily, fresh vegetables and herbs are grown to eat, and are difficult-to-buy (Mentha spicata, Kuzukulağı) crops that have a good yield (herbs and salad vegetables) and popular varieties grown for pleasure (raspberries, sunflowers) or as a reminder of childhood or of home (Momordica charantia).

5.2. Gardening as Work

The characteristics of work according to Arendt are reification and permanence, the use of a pattern, the use of tools and materials, the project character oriented towards an end purpose, the creative act, exchange, self-empowerment, contributing to the building of the world through objects that reach beyond one’s own person.

A long-lasting result of gardening is the garden itself. The cultivated soil, compost, fruit trees, paths, fencing, trellises, herb spirals, seating, and paved areas become tangible, enduring things in a shared world. Here, gardeners proceed in a planned and artful way and turn the garden into a project that follows a pattern and requires certain skills. With the self-made products, the gardeners show what they are, including their cultural uniqueness. They gain appreciation for the work of their hands: They can share and exchange it. The result of their efforts is something special that gives them self-confidence, satisfaction, and a sense of empowerment. Where gardening becomes a creative act, it shows a progression from labor to work. In the Roda-Roda Garden, the lack of a workshop and of storage facilities for tools and materials has a strictly limiting effect on the work. Moreover, the communal garden often does not provide the privacy needed for the process of work, which is particularly limiting for less experienced and confident people.

Both labor and work can be carried out individually, without the presence of others. For Arendt, these two activities are, therefore, basically apolitical [14]. Labor follows necessity, work a specific purpose; only the third, and most human of all activities, speaking and acting, is free of these conditions and can only take place in a vibrant exchange between people.

5.3. Gardening as Action

The characteristics of action according to Arendt are speaking with each other, the appearance of the persons (persona) [14,23] involved, the lack of an end-means dimension, the unpredictability of the result, the fragility of the results as stories, human plurality, concern for the common world, and being active beyond the private sphere.

In communal gardening there are many opportunities for people to speak with each other instead of for or against one another [14]. Permanence and shared responsibility generate an effort to exchange opinions in an open-minded way, especially when it comes to important decisions, allowing all gardeners to share the outcome (Figure 8). In addition, there are conversations on political issues and those that turn private issues into public ones, for example, when some men speak about how to handle xenophobic slogans about gardeners in the nearby pub or when women of different ages and cultural backgrounds exchange views on sex in marriage on a structural level. These particular moments of action happen rarely, and seem banal at first glance, but they matter. It takes courage to appear as a person in the collectively generated public sphere and leave an impression on others. Narratives about the action of living and deceased persons keep shared moments of authentic contact alive. Furthermore, the garden helps to (re)politicize the gardeners insofar as some female gardeners are now involved in the tenants’ council of the housing complex.

Figure 8.

The picture shows gardeners speaking, exchanging arguments, and making joint decisions in a meeting (author’s own photograph).

All three basic human activities of a vita activa in the Arendtian definition (labor, work, and action) take place in the Roda-Roda Garden. The activity of labor is most pronounced in the case study. Work takes place less here because of insufficient framework conditions. Action is the special quality and strength of communal urban gardening. Shared responsibility and daily occasions for interaction have ensured that, even in the face of dissent, there is always something that gardeners can and want to share: care for the common world [32], their common garden.

5.4. The Garden as Private and Public Realm

The three basic activities constitute a private and a public sphere in the garden. Both depend on each other for their existence. Through labor and work, the garden becomes a private space defined by the absence of others. Through co-work and action, the garden becomes a common object that stands between people and, at the same time, connects them. Through action it becomes a political-public space [14,23].

Privacy exists in the Roda-Roda Garden when the gardeners work individually on their beds, when the results of their labor and work belong to them, when they help their neighbors, and seek refuge in the garden because a crowded flat does not provide privacy. The garden becomes part of their private household. Especially women with a Muslim background find it easier to work here on their own because of the private character of the garden. Their husbands were only involved in the initial phase of the garden project and now only attend festivities or when heavy labor is required. All these aspects of privacy are possible, even though there is no direct connection between home and garden.

There is a public sphere in the Arendtian sense in the Roda-Roda Garden when people who were previously strangers are co-present and, in the sense of a radically open political practice, speak with each other, exchange opinions, make decisions together, and appear to each other in plurality. In these moments they create worldly reality [14,23] in the garden.

There is also a social sphere in the garden. When decisions are not made in the modality of action, the garden community functions according to the principles of collective housekeeping. As in the household, much revolves around income, expenditure, cost–benefit tradeoffs, order, and shared ownership. Rules and administration determine this social sphere. They facilitate everyday life and have made it easier for some gardeners to get started. For many gardeners, labor on their plots was the most important thing at the beginning, and communal coordination processes were more of a burden. A different aspect of the social sphere is social distinction. The garden is also a place to meet friends and acquaintances when the flat seems too limited or too private. Socializing around a large table—mostly in the mother tongue—the garden becomes a salon for social activities.

6. The Threefold Spatiality of Vita Activa

We have seen from the case study that CUG can be divided into three distinct activities (labor, work, and action), representing the three basic conditions of human life (life itself, worldliness, and plurality) [32]. Arendt’s distinction, applied to the case study, makes it possible to describe three spatialities of a vita activa based on the political theory of action, and to name the associated framework conditions, as the following section shows. At the end, there is a discussion on the extent to which community gardening, as a spatial expression of a vita activa, enables a revival of the political in citizens and planning concepts.

Debarbieux [27] outlines a tripartite ontology from a geographical perspective, based on the various spatial concepts in Arendt’s oeuvre. Building on and complementing this, and using an empirical example, I identify three spatialities from a planning perspective, directly related to Arendt’s basic activities. The subsistence-productive, (co-)creative, and co-present spaces are related to the basic activities of labor, work, and action and can be seen as a differentiation of phenomenal space. Natural space forms the basis of the mutually influencing and interdependent spaces of basic human activities. The praxeological space is dependent on the other two and exists only as a potential. Therefore, it cannot be planned as such. In contrast, the subsistence-productive, (co-)creative, and co-present spaces can be planned through appropriate framework conditions.

6.1. The Subsistence-Productive Space

Labor creates a subsistence-productive space in the garden with activities linked to natural cycles [14]. Ultimately, labor serves life itself, secures the necessities of life, and forms the basis for production and action. The term subsistence-production points to this genuine production of life and goes beyond the Marxist concept of the reproduction of the workforce [49]. Because of the toil it entailed, in antiquity, labor was the despised task of slaves and women, and later of servants [14] and housewives. It was only in modernity that subsistence was declared non-work in contrast to wage labor [50] and considered something natural and economically unproductive [14]. The recreational landscapes in modern, functionalist, multi-story housing, such as around the Roda-Roda Garden, replicate this modern understanding of labor in built form. There are no courtyards and gardens in which residents can perform everyday labor (care, food production, subsistence), which is displaced into indoor spaces designed primarily to serve the function of dwelling [45]. Whereas in modern consumer society, freeing oneself from the activity of labor is considered desirable [14], for Arendt, freedom means first and foremost ensuring that one is provided with all necessities in order to be able to lead a political life [25].

Planning for a “good life” [30,45,46] involves serious concern for the necessities of life and the labor involved, and treating them as the subject of planning. In Arndt’s view, the “good life” belongs in the private sphere and provides the starting point for a public, political life. By exploring an adapted Innenhaus and Außenhaus concept [51], the following framework conditions for a subsistence-productive space can be defined: a piece of land suitable for gardening; a recognizable boundary that guarantees somewhere “contained and enclosed” for individual and communal appropriation; ownership, not in the sense of possession and wealth, but tied to a specific place in the world and establishing a right of participation in the political; self-determination regarding the use of resources; a close connection between indoors and outdoors; and a use-oriented zoning.

As a private activity, labor needs protection from others [14] and at the same time exchange with others at the neighborhood level [45]. In the Roda-Roda Garden, privacy is established through spatial zoning and rules. Neighborly relations are intensified due to shared responsibility and shared resources and are organized as collective management. Both these aspects of CUG are pre-political in Arendt’s understanding [14].

6.2. The (Co-)Creative Space

Work is grounded in the second basic human condition of worldliness. Fabricated durable artefacts, unlike the ephemeral products of labor, bring about the creation of shared worlds and guarantee the permanence and stability of this world [14]. The garden as a creative space is made up of small projects and creative acts [52] in which gardeners create the garden as a “work of their hands” [14] according to models and their ideas of beauty. I call this spatiality of work in the garden (co-)creative space because in the community garden there is a tension between individual and cooperative work processes. Both can lead to independent and self-determined creation of things, but cooperative fabrication (e.g., of a paved area) needs prior coordination with each other. In the Roda-Roda Garden, most durable material things (shed, furniture) are recycled, bought, or built in other places because there is no workshop in the garden. Except for the specific condition of a weather-protected place to build and store tools and materials, the same framework conditions apply as for labor. The (co-)creative space also belongs to the private sphere.

The planning concept in the case study aimed to create additional spaces for labor and action close to the dwelling. Work was of secondary importance in the initial planning. The construction of a workshop was suggested several times later, but has not yet been implemented. The example shows vividly how planned framework conditions can promote or hinder certain activities [53]. Furthermore, they influence, intentionally or unintentionally, who participates. An analysis according to the basic activities of the vita activa can make such interrelations visible.

With communal urban gardening, the spaces for labor and work are organized in a reduced, densified form with shared and sparingly used resources. It is this sharing and concentration that brings about the decisive benefit compared to the home garden; here, people exist in co-presence [27] and share a common object.

6.3. The Co-Present Space

While labor follows the compelling necessities of life, and work is subject to the end-means relation (Arendt, 2018b: 181f), only the basic activity of speaking and acting is free from the conditionality of life and worldliness. Its purpose is action (praxis) itself, its basic condition human plurality [14]. In speech and action, people adopt different perspectives on the same object and interact on this basis [27]. The garden can become a public space in two ways: on the one hand as an area where issues of public interest emerge and are discussed and on the other hand as an area where individuals appear in the presence of others [54] and show who they are in a situation characterized by plurality [14]. It is less important what the object of public discourse is than how the discourse takes place [13]. For Arendt, politics has no real political substance: It is not about truth, it is about plurality of arguments [9]. Politics emerges in the in-between space and builds itself as a relationship [14]. It belongs to the secular sphere, where a multiplicity of interventions generates a series of unpredictable and uncontrollable events [13] that only endure when they are handed down as memories and histories [14].

For Arendt, polity and public spaces are necessarily particular phenomena [14,55] with a generally limited capacity in terms of the number of members [14]. Through numerical and spatial containment, people can meet as equals in all their diversity and open up to the experience of plurality in discourse [11,14]. Guaranteed egalitarian participation defines the scope of people who are to be involved in the negotiation processes and have a right to be heard and seen. Here, rules can be replaced by speech and action or can be negotiated by the members themselves [28]. There is a connection between privacy and the public sphere, which is constituted as a space between members who are connected to each other through a common object and differentiate themselves from each other. It requires courage to appear there as a somebody. Only those who are willing to exist in togetherness in the future can bear this responsibility [14]. As a result, community gardens can become focal points for political action, places where something new emerges [26] and where people can experience the quality of action in federal, subsidiary, and autonomous organizational structures [24] even within a functional environment.

These everyday occasions and the care for the common world, in this case the garden, make it possible to have disputes, to argue with each other, and to gain new mutual understanding from the dispute. There are enough occasions for quarrels, as the case study shows. However, in almost all cases, a common solution is sought. Of course, language plays a central role here. In case of communication problems, even more efforts are needed from all sides to manage the exchange of opinions. In 10 years, only one person left the garden after an unsolvable dispute. CUG provides an opportunity to practice political action in everyday life. Except for two older men, the Roda-Roda gardeners have not previously engaged in political activities. Most of them are so preoccupied with the necessities of life (jobs, job search, poverty, health issues, care for children, grandchildren, or the elderly, etc.) that they find no time to become politically involved. Most did not even see that as an option for themselves. In the garden and for the garden community everyone finds the time to act, except those with extreme burdens who need the garden for their personal relaxation. As a result of this experience, some gardeners have become active outside the garden, for example, on the tenants’ board. Additionally, they complain about the de facto lack of equality in some official political bodies because that is what they know and appreciate in the garden.

Public space is not necessarily a specific topological space (Benhabib, 1991). It opens everywhere for everyone [13]. It can emerge in the town hall or the town square and, likewise, in a community garden. However, the analysis shows that well-organized subsistence, the creation of a common world, and occasions for the co-presence of people increase the potential for public space to be constituted in the same place where everyday life takes place.

While the public-political space cannot be planned, the co-present space is something like a pre-stage of the public space, which can be planned using adequate framework conditions. According to the case study, the central framework conditions of a co-present space are boundaries, ownership (linked to a right of egalitarian participation), a place to meet, and a common object with which people are engaged in a diversity of perspectives [14]. These kinds of boundaries and ownership are not about privatization and commercialization of common resources, which is the common movement’s central critique of enclosures [56]. Ownership here is not about possession in the sense of an economic value of a resource. It is about the basis of participation in decision making about how to deal with that resource. Ownership is nothing more and nothing less than having a location in a particular part of the world and, therefore, being part of the public sphere [31].

A communal urban garden offers many occasions to enact plurality in speech and action. Neighborhood gardens especially support plurality because they are not primarily based on an intentional community, but on the local community and a specific place as a common context [57]. A garden provides daily reasons to visit it, encourages activity, and provides an opportunity to relate to other people on simple topics such as tomatoes.

7. The Transformative Character of the CUG as Vita Activa

To use a metaphor by Arendt, the Roda-Roda Garden lies in the deserted lawns of the housing estate like an ‘island in a sea’ of the Social [24]. The case study shows how CUG can transform the sphere of the Social [14] into private and public spaces in the sense of vita activa. The modern functional housing estates of consumer society with their decorative green spaces have, as a built form, lost their mediating capacity to articulate privacy from the public sphere [40]. The dwellings and green spaces serve to regenerate the labor force. They are bureaucratically administered places of function recreation and leisure. Bureaucracy, a “rule of nobody” [14,26], assumes a hypothetical uniformity of economic social interest and a hypothetical unanimity of common opinions [14]. Human affairs are treated as natural conditions [33]. The focus is on economic processes and considerations of utility (outsourcing, cost reduction, lowest-bidder principle) and generate collective housekeeping and behavior. As a standardized form of the supposed collective need for regeneration, these green spaces are the same for everyone and, thus, equally “of no use”. While action is based on the plurality of people, management is based on the homogeneity of people [14].

CUG, in the sense of a vita activa, is not, in fact, compatible with administration-oriented urban planning. In her history of US community gardens, Lawson [58] shows how children’s play, as opposed to gardening, was integrated into urban planning as public services for recreation and child socialization as early as in the 1920s. She concludes that community gardens, because of their multifunctionality, could not be standardized and regulated like playgrounds. From analysis of the case study with the help of Arendt’s political theory of action, it can be added that CUG carries the radical political and ecological potential [7,59], which, from the administration’s point of view, is unpredictable and incompatible with standard urban planning.

Many city administrations, like Vienna, today offer gardening as a monofunctional leisure activity on public land. Without the potential for labor, work, and action, gardening can be integrated into the social sphere of the city in a standardized way, analogous to playgrounds. From leased plots to raised beds in parks to guerrilla gardening, everything is offered as a public service now [60]. In this way, the municipal administration directs increasing demand for urban gardening into orderly and controllable directions in which people behave instead of act. In this process, participation is also limited and remains within the regimes of public administration [8]. The municipal-influenced community gardens in Vienna have a project-like character, informal networks with low legal and financial security [48]. Thus, the preconditions for a public-political space, which is constituted through action and is a condition for it, are missing [11] and must first be set up—often against the existing rules and design.

As the case study shows, communal urban gardening can transform the social sphere of administered green areas into subsistence-productive, (co-)creative, and co-present spaces. The planning of such spaces for a vita activa is characterized by three features: (1) Planning focuses on suitable framework conditions rather than on the design of functions, because the spaces cannot be planned in the sense of work (purpose-means binding, accomplished final result), (2) planning has a conception of private and political-public spaces, and (3) it understands the planning process, beyond the organization of spatial, social, and economic framework conditions, as a genuinely political experience of “acting in concert” in a participatory empowerment process.

8. Re-Politicization by Gardening

Urban gardening has long been seen as a practice of counterplanning. The (re)appropriation of public space was fought for with autonomous, citizen-led action in the tradition of the “right to the city” [61]. Informal planning [62] is no longer just a contrast to institutional planning. It complements, transforms, and contaminates formal planning with alternative solutions. In informal planning, the roles of the actors involved are mixed, which, in principle, allows an exchange of opinions at eye level and the negotiation of new solutions. At its best, informal planning can be a process of empowering citizens in self-producing public space [62]. Here, the level of (re-)politicization is addressed that goes beyond a substantivist conception of the political [27]. Political gardening can involve articulating and materializing visions for counter-neoliberal urban transformation [6]. But it also means to be active in the sense of a vita activa and to (re-)experience speaking and acting in everyday life. This forms the basis for transformation, something that is, however, easily overlooked. Unlike discourse-based forms of political activism, speaking and acting come together in the CUG, which is what makes it so attractive [6]. This expands the range of actors, as people who initially only want to garden also come into contact with political action in everyday life. For Arendt, every human being is capable of politics. The act of speaking and acting, of taking an active role in public and taking political initiative, is always a venture [11], and involves the transformation of the individual. In community gardening they can experience “acting in concert” in connection with the “labor of their bodies” and the “work of their hands”. Here they can be active not only out of necessity, but also because they are free to do so, combining the elements of a private “good life” and a public life in the sense of a vita activa. In order for this (re-)politicization to be open to many people in a post-political period of neoliberal governmentality, including those who cannot fight for their own right to the city, planning is needed that combines poiesis (work) and praxis (action) to create suitable framework conditions for autonomous activity and, at the same time, supports the empowerment process. Political gardening with Arendt means that the political is inherent in the gardening and planning process and is not imported into it as a separate sphere. In this sense, CUG calls for a (re-)politicization of city dwellers and of the planning process.

9. Conclusions

This paper was about how CUG can transform monofunctional green spaces of a social sphere into spaces for a vita activa, where people are not only active next to and for each other, but also with each other. This article is a contribution to the exploration of Arendt’s concepts of space by testing them against the contemporary phenomena of the CUG. With the help of a case study in Vienna, spatialities of the vita activa are articulated in connection with Arndt’s basic activities and opened up for planning theory.

We have seen that the three basic human activities of labor, work, and action take place in the CUG. In connection with these activities, three different spaces for vita activa can be named. Two of them, the subsistence-productive space (labor) and the (co-)creative space (work), are part of the private sphere. The third space, on the other hand, referred to here as co-present space, is the preliminary stage of a political-public space and belongs to the public sphere.

The analysis of a garden project in Vienna that was accompanied over a period of 10 years shows that the various spaces are created and maintained through an interplay of framework conditions and activities. The framework conditions for the spatial constitution of labor, work, and action in the CUG are containment, ownership (in the sense of sovereign rights of use), egalitarian participation, plurality, and orientation of spatial and socio-economic organization towards the three different activities. The basis of planning is the landscape planning concept of Innenhaus and Außenhaus. When applied to CUG, it was expanded to include the activity of action and, thus, the political dimension.

Looking at the phenomenon from the perspective of Arendt’s political theory of action shows that CUG creates both a private and a public sphere in one place and thereby tends to oppose the social sphere of administering and behaving. While functionalized forms of urban gardening can be integrated into existing administrative processes in a similar way to playgrounds, CUG as vita activa challenges government, administration, and urban planning with its implicit demand for self-organization and political action. This can be deduced from the case study as well as from the history of urban gardening. The example clearly shows that CUG has potential for the (re-)politicization called for by Arendt. However, this requires a planning approach that combines both poiesis and praxis.

Funding

The original fieldwork was funded by Wiener Wohnen and Municipal Department 57—Vienna Women’s Affairs (MA 57) from 2009 to 2011. The 2010 evaluation was funded by Municipal Department 57—Wiener Wohnbauforschung (MA 50).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank my colleagues Marlene Mellauner, Christiane Brandenburg, Ewin Frohmann, and Doris Damyanovic for their support and Michael Ornetzeder for his preserving advice and excellent feedback. I gratefully acknowledge the members of the Roda-Roda Garden community for everything I learned through our collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lawson, L.J. City Bountiful: A Century of Community Gardening in America; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Milbourne, P. Everyday (in)justices and ordinary environmentalisms: Community gardening in disadvantaged urban neighbourhoods. Local Environ. 2012, 17, 943–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D.C.; Samuels, M.; Harman, A.E. Growing healthy kids: A community garden–based obesity prevention program. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, S193–S199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Jagt, A.P.N.; Szaraz, L.R.; Delshammar, T.; Cvejić, R.; Santos, A.; Goodness, J.; Buijs, A. Cultivating nature-based solutions: The governance of communal urban gardens in the European Union. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, B.; Henryks, J.; Pearson, D. Community gardens: Sustainability, health and inclusion in the city. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certomà, C.; Tornaghi, C. Political gardening. Transforming cities and political agency. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, M.; Tyman, S.K. Cultivating food as a right to the city. Local Environ. 2014, 20, 1132–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, B.; Boelens, L. Self-organization in urban development: Towards a new perspective on spatial planning. Urban Res. Pract. 2011, 4, 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, R. The Failing Technocratic Prejudice and the Challenge to Liberal Democracy. In The Emergence of Illiberalism: Understanding a Global Phenomenon; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tálos, E. Vom Siegeszug zum Rückzug: Sozialstaat Österreich 1945–2005; BoD–Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Straßenberger, G. Hannah Arendt zur Einführung; Junius: Hamburg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Diebäcker, M.; Ranftler, J.; Strahner, T.; Wolfgruber, G. Neoliberale Strategien und die Regulierung sozialer Organisationen im lokalen Staat. Teil I. soziales_kapital. Einleitung 2009, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cavarero, A. Politicizing theory. Political Theory 2002, 30, 506–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, H. Vita Activa oder Vom Tätigen Leben; Piper: München, Germany; Berlin, Germany; Zürich, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yazan, B. Three approaches to case study methods in education: Yin, Merriam, and Stake. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 134–152. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. Revised and Expanded from “Case Study Research in Education”; ERIC: Berlin, Deutschland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hilpert, T. Die Funktionelle Stadt: Le Corbusiers Stadtvision-Bedingungen. In Motive, Hintergründe; Viewig: Braunschaig, Germany, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Mayrhofer, R. Co-Creating community gardens on untapped terrain – lessons from a transdisciplinary planning and participation process in the context of municipal housing in Vienna. Local Environ. 2018, 23, 1207–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.A. Hannah Arendt, the Recovery of the Public World; St. Martin’s Press: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, A. Hannah Arendts Platz im spätmodernen Denken. SIMON Shoah: Intervention. Methods Doc. 2017, 4, 112–122. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, H. (Ed.) Was Ist Politik? Fragmente aus dem Nachlaß; Piper: München, Germany; Zürich, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, H. Über Die Revolution; Piper: München, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, H. Die Freiheit, Frei zu Sein; dtv.: München, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, H.; Reif, A. Macht und Gewalt; Piper: München, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Debarbieux, B. Hannah Arendt’s spatial thinking: An introduction. Territ. Politics Gov. 2017, 5, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhabib, S. Modelle des Öffentlichen Raums: Hannah Arendt, Die Liberale Tradition und Jürgen Habermas; Soziale Welt, Nomos: Baden-Baden, Germany, 1991; pp. 147–165. [Google Scholar]

- Benhabib, S. Feminist theory and Hannah Arendt’s concept of public space. Hist. Hum. Sci. 1993, 6, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülbusch, I.-M. Innenhaus und Außenhaus—Umbauter und Sozialer Raum; Gesamthochschule Kassel: Kassel, Germany, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, H. The Human Condition; University of Chicago Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Loidolt, S. Phenomenology of Plurality: Hannah Arendt on Political Intersubjectivity; Routledge: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pitkin, H.F. Justice: On relating private and public. Political Theory 1981, 9, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, H. (Ed.) Menschen in Finsteren Zeiten; Piper: München, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf, V. A Room of One’s Own: Three Guineas; Penguin: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, M.; Church, A. Cultivating natures: Homes and gardens in late modernity. Sociology 2001, 35, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, N.; Church, A.; Gabb, J.; Holmes, C.; Lee, A.; Ravenscroft, N. Growing intimate privatepublics: Everyday utopia in the naturecultures of a young lesbian and bisexual women’s allotment. Fem. Theory 2014, 15, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dünne, J.; Günzel, S.; Doetsch, H.; Ludeke, R. (Eds.) Raumtheorie: Grundlagentexte aus Philosophie und Kulturwissenschaften; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Honig, B. Toward an agonistic feminism: Hannah Arendt and the politics of identity. In Feminists Theorize the Political; Routledge: University Park, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 233–254. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. Labour, Work and Architecture: Collected Essays on Architecture and Design; Phaidon Press: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Böse, H. Das Außenhaus verfügbar machen. In Notizbuch 10 der Kasseler Schule; Freiraum, A.G., Vegetation, Eds.; Gesamthochschule Kassel: Kassel, Germany, 1981; pp. 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, O. Das “ganze Haus” und die alteuropäische “Ökonomik”. In Sozioökonomische Perspektiven: Texte zum Verhältnis von Gesellschaft und Ökonomie; facultas.wuv: Wien, Austria, 2014; p. 97. [Google Scholar]

- Hülbusch, I.-M. Außenhaus. In Notizbuch 10 der Kasseler Schule; Freiraum, A.G., Vegetation, Eds.; Gesamthochschule Kassel: Kassel, Germany, 1991; pp. 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowski, M. Freiräume im Garten: Die Organisation von Handlungsfreiräumen in der Landschafts- und Freiraumplanung. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität für Bodenkultur Wien, Wien, Austria, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kölzer, A. Wurzeln im Alltäglichen.: Die Bedeutung der Arbeit am Symbolischen für eine Subsistenzperspektive in der Landschafts- und Freiraumplanung. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität für Bodenkultur Wien, Wien, Austria, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mies, M.; Bennholdt-Thomsen, V. The Subsistence Perspective; Zed Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gartenpolylog Gartenkarte. Available online: https://gartenpolylog.org/willkommen-beim-gartenpolylog (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Exner, A.; Schützenberger, I. Creative Natures. Community gardening, social class and city development in Vienna. Geoforum 2018, 92, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mies, M. Housewifisation–Globalisation–Subsistence-Perspective. In Beyond Marx; Linden, M., Roth, K.H., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 209–239. [Google Scholar]

- Meier-Gräwe, U. Hauswirtschaftliche Tätigkeiten als produktive Arbeit: Eine kurze Geschichte aus haushaltswissenschaftlicher Perspektive. In (K) Eine Arbeit Wie Jede Andere? Die Regulierung von Arbeit im Privathaushalt; Scheiwe, K., Krawietz, J., Eds.; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 135–164. [Google Scholar]

- Mayrhofer, R. Chili und Ribiselkuchen: Gemeinschaftsgärten im Wiener Gemeindebau als gemeinschaftliches Außenhaus. Momentum Q. 2019, 8, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Walker, A. Auf der Suche nach den Gärten Unserer Mütter: Essays; Frauenbuchverl: München, Germany, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Böse, H. Die Aneignung von städtischen Freiräumen—Beiträge zur Theorie und sozialen Praxis des Freiraumes. In Notizbuch 22 der Kasseler Schule; Freiraum, A.G., Vegetation, Eds.; Arbeitsberichte des Fachbereichs Stadt- und Landschaftsplanung an der Gesamthochschule Kassel: Kassel, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Dikeç, M. Space as a mode of political thinking. Geoforum 2012, 43, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigwart, H.-J. Hannah Arendt und die Grenzen des Politischen. Raum und Zeit. In Denkformen des Politischen bei Hannah Arendt; Campus: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2014; pp. 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich, S.; Bollier, D. Commons. Für eine Neue Politik Jenseits von Markt und Staat. 1. Auflage; Transcript: Bielefeld, Germany, 2012; pp. 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hamers, D.; Tennekes, J. Will enclosed residential domains affect the public realm of Dutch cities? Three theoretical perspectives. Plan. Theory 2015, 14, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, L. The Planner in the Garden: A Historical View into the Relationship between Planning and Community Gardens. J. Plan. Hist. 2004, 3, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosol, M. Gemeinschaftsgärten in Berlin: Eine qualitative Untersuchung zu Potenzialen und Risiken bürgerschaftlichen Engagements im Grünflächenbereich vor dem Hintergrund des Wandels von Staat und Planung. Ph.D. Thesis, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Buch, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bio-Forschung-Austria Gemeinschaftsgärten und Nachbarschaftsgärten. Available online: https://www.garteln-in-wien.at/ (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Schmelzkopf, K. Incommensurability, Land Use, and the Right to Space: Community Gardens in New York City1. Urban Geogr. 2002, 23, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certomà, C.; Notteboom, B. Informal planning in a transactive governmentality. Re-reading planning practices through Ghent’s community gardens. Plan. Theory 2017, 16, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).