1. Introduction

In 2015, the United Nations set 17 sustainable development goals (i.e., UN SDGs) to be achieved by 2030. The SDGs seek to address complex societal challenges that scholars have often described as wicked problems [

1], messes [

2], or, more recently, grand challenges [

3,

4,

5]. Such challenges include poverty, hunger, education, climate crisis, gender equality, water sanitation, biodiversity loss, and many more, all of which make achieving a better and more sustainable future for all difficult at best.

Admittedly, the UN SDGs have made significant inroads into the global business community and successfully elicited commitments from companies, as can be evidenced in the 2018 Oxfam report, which showed that 62% of companies have made a public commitment to the SDGs [

6]. However, despite such seemingly high commitment and uptake, the pace of change is nowhere near fast enough to reach these goals by 2030. Unfortunately, the latest UNESCAP SDG progress report suggests that the Asia-Pacific region will likely miss all the goals by 2030. Further, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, tracking inequality and progress made against the SDGs, based on 18 social indicators, also found, in their 2020 goalkeepers report, that the world has actually regressed on the vast majority of the global goals.

In a sense, this regression is not surprising. The nature of the challenges associated with the UN SDGs is so wickedly complex and interconnected, with conflicting interests of multiple actors, it is easy to reject any quick and easy solutions. The issues thus remain stubbornly persistent in the nature of wicked problems [

7]. Moreover, such wicked problems are fundamentally distinct from traditional problems, where there were clear problem definitions and easily traceable cause and effect relationships [

1]. While traditional, ‘tame’ problems [

1] can be solved in a linear manner, often by identifying best practices, wicked problems that manifest in complex environments reject such linear approaches [

1,

8]. In complex environments, where many relationships among elements are invisible, it is hard to clearly define what the problem is, and no single silver bullet can solve the problem, because the outcomes are often unpredictable and bring about unintended consequences [

1,

9,

10].

To address these wicked problems in the increasingly interconnected, turbulent, and disruptive environment, a number of scholars have suggested a completely different approach from traditional models of innovation and problem solving, taking a systems perspective [

9,

11,

12]. A system is defined as “an interconnected set of elements that is coherently organized in a way that achieves something” [

13]. In the systems perspective, it is important to look at the whole, not just the parts, and focus on the relationships among the system’s elements, which in living systems, such as organisms and human socio-economic systems, are dynamic, interactive, and nonlinear. A systemic perspective thus emphasizes how different systems elements are “interconnected and subject to non-linear, difficult-to-model dynamics because of feedbacks and delays” [

8,

11]. From this standpoint, systemic problems are messy and difficult to define, and the outcomes of actions are often unpredictable. Therefore, traditional, top-down models of intervention do not necessarily work or they can create unintended consequences [

1]. In order to address complex and wicked problems, the systems perspective suggests nudging key “leverage points” within the system—“places within a complex system (a corporation, an economy, a living body, a city, an ecosystem) where a small shift in one thing can produce big changes in everything” [

14].

In this paper, we focus on and elaborate on the role of a new form of organizing that embodies the systems perspective and potentially facilitates the timely achievement of SDGs by bringing about transformational changes at the systems level: the transformation catalyst (TC) [

15]. TCs build on a legacy of other types of catalytic entities, such as catalytic alliances (CAs), global action networks (GANs), and field catalysts (FCs). We argue that TCs are distinctive in their explicit focus on systems that make them more capable of tackling wicked problems, such as sustainability and climate change, inequality, and other systemic issues, which are complex and interconnected in nature. While the previous catalytic organizations share a lot of roles in common with TCs, such as connecting, cohering, and amplifying different actors’ efforts to achieve change, they did so in a rather siloed manner, whereas TCs not only connect and cohere actors, but also issues. They aim to make transformational changes at the systems level. Therefore, this paper is motivated by the following research question: how do transformation catalysts describe the catalytic work that they do?

To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first empirical study of TCs. By identifying 27 TCs and analyzing their websites, we document how TCs are distinct from other entities, in their transformational agenda, catalytic actions, sensemaking, and systems orientation, all of which make TCs better suited for tackling complex problems and facilitating transformational changes at the systems level. We believe and hope that by providing new insights into what these new entities do and how they differ from their antecedents, our paper will contribute to bringing about the timely achievement of transformational aspirations such as the SDGs (though we do note the problematic nature of SDG 8, with its emphasis on continual growth on a finite planet).

2. Antecedents of Transformation Catalysts

Transformation catalysts have been defined as follows:

“Transformations catalysts (TCs) are promising organizing innovations specifically designed to address complexly wicked societal problems and opportunities and bring about purposeful system transformation. … Specifically, they connect, cohere, and amplify efforts of other initiatives in an attempt to overcome the fragmentation and lack of impact …. They help coalitions of actors emerge shared visions, goals, aspirations, or other narratives that enable them to align their efforts, even while they pursue their individual agendas”.

In chemical reactions, the catalyst is an agent that brings about rapid changes without itself necessarily changing. In social circumstances, the idea of the catalyst has taken on a broader meaning of precipitating events or changes. In the case of TCs, those changes are transformative in nature, attempting to change the fundamentals of a situation [

15].

TCs represent a new and still emerging way of organizing that is uniquely oriented to fostering transformational system change at a large scale [

15], and that may offer some hope for dealing with the complexities with the wicked or even super wicked [

16] problems associated with the UN SDGs and similar issues. We briefly explore TCs’ predecessors below, before moving on to analyze how TCs view their own efforts in transformative or catalytic action.

In the 1980s, the idea of catalytic alliances was introduced [

17] as catalytic social action, as follows: …catalytic social action involves the temporary alliance of organizations and their members to deal with an important problem…to foster longer-term change, without necessarily changing the nature or structure of the organizations in alliance (p. 394).

The social entrepreneurs who founded CAs used the following three mechanisms to engage others: a clear social vision “that has the potential to reshape public attitudes” (p. 394), significant personal credibility, and resources including networks, relationships, and followers’ commitment to the collective purpose of the project. In 1995, the idea of catalytic alliances was elaborated, specifically identifying the characteristics of the CAs of the era.

Catalytic alliance initiatives operate at the leading edge of social reform, using the media as a strategic resource to place an issue on the public agenda and change public attitudes. Designed to leverage limited resources into major social change, by stimulating others (people and organizations) to take action, rather than intervening directly to affect a social problem, catalytic alliances work through an extensive network of other organizations to achieve indirect shifts in public attitudes. The objective is to spark a commitment to social action in others, through a high-profile media process, to move an issue onto the public policy action agenda, so that more traditional organizations (public, private, nonprofit) can effectively work on the problem [

18] (pp. 951–952).

More-complex forms of networks that also emphasize the (catalytic) transformation of a societal issue are referred to as issue networks [

19], global action networks (GANs) [

20], and global governance organizations [

21]. GANs are multi-stakeholder global networks that tend to focus on particular issues. For example, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI; environmental, social, and governance reporting for organizations), the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC; forest sustainability), and the Global Water Partnership (GWP; water security) are all GANs. GANs share some TC characteristics, but generally limit their actions to particular approaches to solving their focal issue (e.g., corporate reporting, forest certification, water resource management). They take direct action to change the issue through everything from local- or industry-based certification, through national–regional–global processes to create supportive policy and market dynamics.

In 2018, Hussein and colleagues introduced the idea of the field catalyst (FC), which, similarly to CAs and GANs, “sought to help multiple actors achieve a shared, sweeping goal” [

22] (p. 50). The authors argued that such FCs shared the following four characteristics: emphasis on “achieving population-level change” by building or strengthening a field, “influenc[ing] the direct actions of others, rather than acting themselves”, focusing on getting things done (not achieving consensus), and being “built to win, not to last” (p. 50). Hussein and co-authors, similarly to others before them, noted the importance of the vision/mission. They indicated that the vision needed to be “big enough for stakeholders to rally around, yet specific enough to make a measurable difference” through a “road map for change” by, in a sense, connecting the dots among enterprises already engaged on the relevant issue or in the field (p. 51).

There are other antecedents to TCs. For example, innovation brokers or intermediaries work, typically in the context of community-based initiatives (CBIs), to develop and maintain networks of similarly minded organizations, by creating an interstitial (between organizations) infrastructure [

23] (see [

24] for types of such entities). This infrastructure enhances the capacity of CBIs to network, collaborate, and learn from each other, as well as to engage in policy activism [

23]. CBIs perform a type of curatorial role that is necessary for navigating complexity that helps connect previously unlinked actors in a catalytic way and work to ensure that knowledge is shared by diverse actors across multiple scales [

25].

Innovation brokers or intermediaries serve useful functions by creating networks of innovators, working collaboratively around similar visions, in ways that enhance support for innovations, and working across multiple boundaries [

26,

27]. Similarly to TCs, innovation brokers emphasize the importance of a good story or narrative that compels relevant actors to take action and taps particular windows of opportunity that exist across different types of innovators [

27]. Unlike innovation brokers, however, TCs go beyond innovation systems and facilitate multi-stakeholder innovation, and magnify efforts [

28].

Catalytic change also features prominently in Christensen’s notion of catalytic innovation for social change [

29]. In Christensen’s framing, catalytic change is explicitly oriented to product/market innovations by companies, rather than the societally or systems-oriented actions of TCs. Though such innovations may serve social purposes, and bring about significant changes in different product/market arenas, catalytic innovations, in Christensen’s framing, are firmly based in markets, rather than attempting the broader systemic transformation of catalysis at which TC’s aim.

Looking at a related structure, Selsky and Parker [

30] (p. 850) synthesized the literature and defined cross-sector social partnerships (CSSPs) as “cross-sector projects formed explicitly to address social issues and causes that actively engage the partners on an ongoing basis”. Generally speaking, CSSPs directly deal with specific issues, rather than working catalytically to cohere or align other actors who are dealing with relevant issues, to amplify their impact. In other words, while they are cross-sector and relationally based, they directly work on whatever the relevant issues are, though none are necessarily oriented towards catalytic or transformative system change as TCs are.

The literature on CSSPs also highlights the role of partnership brokers [

31,

32,

33]. Although partnership brokers, similarly to TCs, convene potential partners and consolidate robust working relationships [

33], working “to steer and support the building of partnerships” [

31] (p. 2), they also differ from TCs in a number of important ways. First, partnership brokers can be internal (i.e., from within one of the partner organizations) or external (i.e., independent of the partner organizations), whereas TCs are solely external, in that they do not take direct actions themselves, but instead focus solely on connecting, cohering, and amplifying works of other actors. Secondly, the changes that partnership brokers intermediate are often issue-specific and not necessarily transformational in nature.

3. Identifying What Transformation Catalysts Do

TCs have emerged in two interconnected contexts. First is a growing recognition of the need for systemic transformation change, identified by many observers, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, and as articulated in the SDGs and the climate emergency. Understanding this context combines with the awareness of the complexly wicked nature of the systems that need to change, which means that no single actor will be able to bring about transformation [

34]. The other context has a growing capacity to work catalytically with a variety of actors, often online, connecting efforts that are attempting such transformational change in new ways, to bring about more effective, situationally relevant, and impactful transformation of whole systems at different levels of analysis. The emergence of Zoom and similar platforms has enabled new types of connections and alliances that might not have been feasible in a less digitally connected era, or where people were still able to get together easily in person.

The rest of this exploratory paper analyzes and synthesizes what the 27 entities that have been identified as TCs articulate on their websites about what their work is and how they approach it. In exploring these TCs’ work, we hope to build a solid conceptual framework that helps change agents to better understand the nature of transformative catalytic action on societal issues.

Research Orientation and Methods

TCs are a relatively new organizational phenomenon, hence little is known about how they define and implement their catalytic work. Because this paper is exploratory in nature and descriptive in its results, both the initial identification of TCs and the findings must be considered to be tentative. We focused on the following research question: how do transformation catalysts describe the catalytic work that they do? Using their descriptions, we hoped to be able to determine what is meant by catalytic action in the context of the transformation catalyst. As described below, data about their activities and aspirations were collected from candidate TC websites, using the aspirational statements on their webpage, as well as statements associated with their vision, mission, values, “what we do”, “about” pages, or similar, to provide as much insight as possible into their activities.

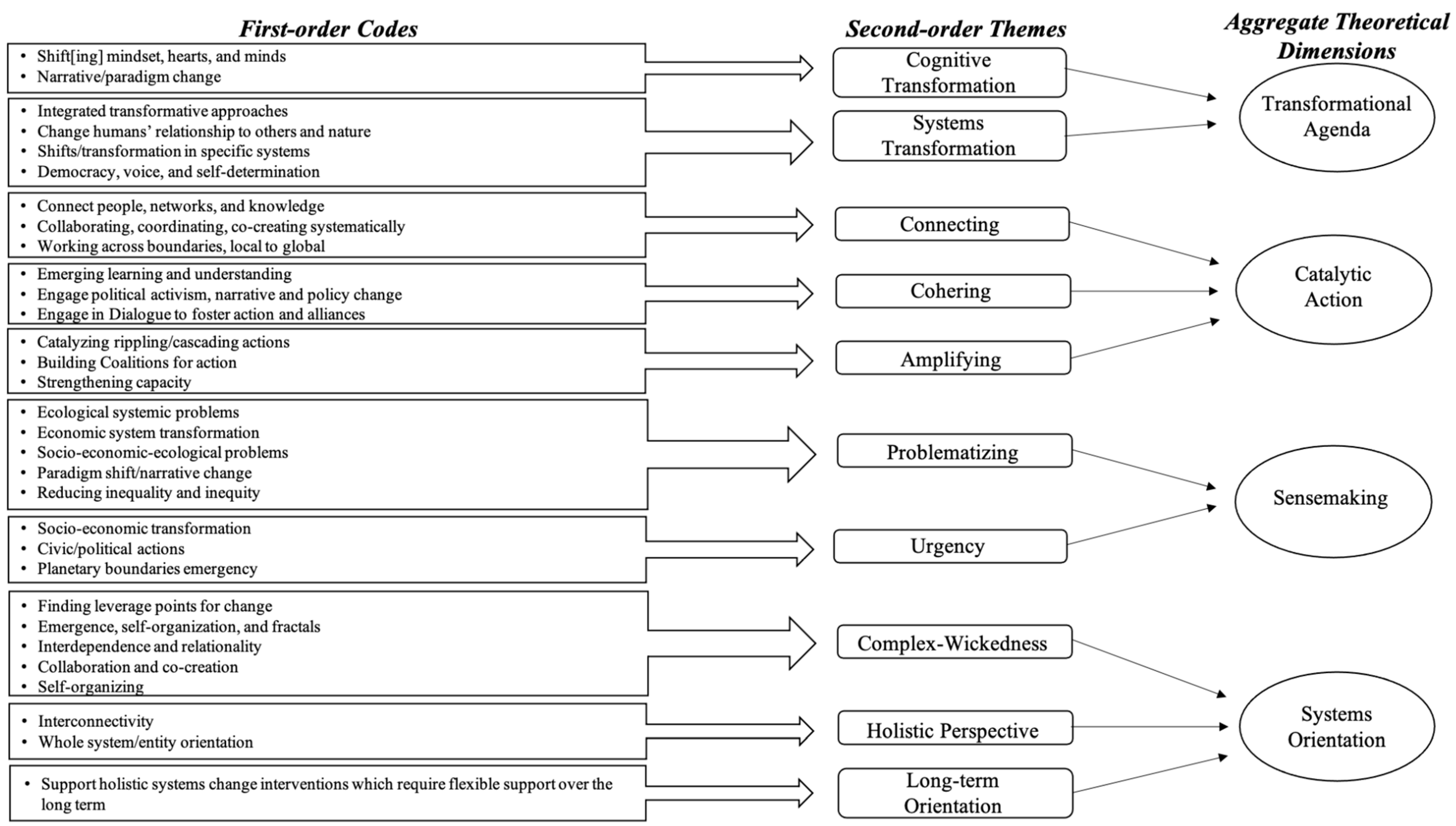

The data were gathered into individual Word documents for each entity and input into the NVivo program for coding. Initially, we drew from the Transformations Catalyst paper mentioned earlier, to develop tentative coding categories, then the two authors separately coded data from about a quarter of the websites, to see what additional categories emerged. After consultation with each other, we developed a common framework with four major categories (transformation agenda, catalytic action, sensemaking, and systems orientation), with relevant subcategories, as described in the next section (see coding in

Figure 1).

More specifically, developing these criteria was actually part of an iterative, inductive (and admittedly somewhat circular) research process that enabled us to both define and discover TCs, and also pointed us in the direction of appropriate codes later on. One of the authors had been working intensively with several organizations that were clearly identifiable as TCs and had some initial understanding of what we were looking for. Using a version of the general definition of TCs above and exploring a number of possible candidates, we went through an iterative process of exploring different entities’ websites. In doing so, we developed the following four main qualifying criteria for potential TCs (see details in

Supplementary Material S1): transformation agenda; catalytic action of some sort, sensemaking, and systems orientation. One of the authors coded about a quarter of the TCs candidates using the working list, adding new ideas and details as they emerged from the data. Each of these criteria became the main code category, with final subcodes emerging from the data itself in an iterative process. We solidified the criteria once saturation was reached and no new criteria were emerging (also eliminating any existing criteria that did not seem to be present in the data). Once the codes were established (see

Figure 1), the other author similarly went through the same 25% of TC candidates as a validity and reliability check, then finished coding the rest of the data for all of the TCs (note: all

Supplementary Materials are online).

This process enabled us to tentatively identify 27 entities as TCs. Of the initial 41 candidates identified, 14 were eliminated as they did not meet these criteria. We then gathered rich, qualitative data from the websites of all the possible TCs, i.e., information that described their vision, mission, “how we work”, “about us”, and related categories, during October 2020. The data revealed the following four main sets of activities, most of which had subcodes, which will be discussed in detail in the next section: transformation agenda (what and where), systems orientation (approach), catalytic action (who and how), and sensemaking (why and when). Once all the data were coded, we began to analyze the data, starting by developing both word clouds and Excel spreadsheets that indicate the top words used in each code, to get a sense of how each category was framed and what types of activities were involved. Then, we created documents of key phrases from each code category that provided more in-depth, qualitative rounding to each of the codes. This latter step enabled us to synthesize each of the codes and subcodes, providing the needed insight into how these TCs take action and what they mean by catalytic actions, as observed in

Table 1 and discussed below.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper has explored, in depth, the actions associated with the emerging organizational entity, called the transformation catalyst (TC), using data from their websites. Transformation catalysts represent an emerging way of organizing change agents and initiatives that we argue are needed to integrate transformation initiatives, so that they can more effectively address the complexity, interconnectedness, and wickedness of achieving transformational goals, such as the SDGs and other such efforts. As

Table 1 illustrates (and the

Supplementary Materials show in detail), the catalytic actions undertaken by TCs take many forms. The data indicate that system transformation, as defined by TCs, means dealing with whole systems and systemic solutions aimed at bringing about fundamental changes, through working to shift cognitive frames that reorient the mindsets and paradigms that help to explain a given system. It also means emphasizing systemic change—change of whole systems—through integrated approaches, shifting the core understanding about the place of human beings in the world, with respect to nature, working specific domains of change, and ensuring that all voices can be heard.

As defined by the TCs we studied, catalytic actions emphasize the “who” and “how” of bringing collaborators, partners, and allies together in new ways. This connects works across boundaries, so that allies can begin collaborating, coordinating, and co-creating initiatives oriented towards systemic change. TCs also work to help their allies cohere their efforts in a variety of ways, including developing insight through new learning and understandings, engaging in political activism and policy change, and creating dialogues that help to foster new types of alliances and actions. Amplifying action means strengthening and empowering diverse groups so that they can mobilize to take more effective action. This amplification process is aimed at creating ripples of new actions that result from initial actions, building coalitions, and strengthening a variety of capacities, e.g., for leadership, for action-taking, and for understanding the system, among others.

The sensemaking activity of TCs addresses the “when” and “why” of the need to take catalytic action, particularly around complex and interconnected issues, such as the ones embedded in the SDGs. Sensemaking means acknowledging the reason for (why) system transformation—and the urgency associated with that. That process involves problematizing specific domains, topics, or ways of doing things that are creating systemic problems, for example, ecological, economic, or inequality issues. In turn, problematizing creates a sense of urgency around the transformative impulse, engaging targeted actions in socio-economic, civic and political, and biogeophysical (planetary boundary) domains, and presumably in the future, others.

Accomplishing all of this change means adopting a systemic orientation that includes systems thinking, almost as a matter of conceptualization of the problem. The work of TCs makes it increasingly clear that systemic change of the sort envisioned by SDGs cannot happen without the integration of numerous initiatives aiming at similar goals—and demands a systems approach. The language of complexity and wicked problems thus finds its way into many descriptions of what TCs are doing, e.g., words such as leverage points, emergence, interdependence, and relationality, along with co-creation and self-organization, which are common descriptors. In addition, taking a long-term orientation is a given for many TCs, who assume a holistic approach to the issue or problem domain that recognizes interconnectivity and takes a whole system, rather than piecemeal, orientation.

An understanding of what TCs are and how they operate is timely and important, because wickedly complex challenges associated with the UN SDGs require transformational change, not incremental or piecemeal approaches. Such transformational changes cannot be achieved by any single entity alone, be it government agencies, businesses, or NGOs. What is needed is the collective and coherent action of many initiatives guided by common aspirations. We believe that TCs may be a ray of hope in this context of complexly wicked problems. Moreover, by analyzing how the entities identified as TCs actually undertake their work and identify commonalities across such entities, this study provides those interested in system transformations with an understanding of what elements are needed if TCs are to work, and how new ones can emerge.

This research has limitations. As we mentioned earlier, our paper is exploratory in nature and the 27 organizations that we identified in this paper are by no means an exhaustive list of TCs. Building on the criteria that we developed in this paper, future studies could look more into other existing TCs and see if there are other ways that TCs are distinctive from other types of organizations, and gain more insight into the domains in which they are active, how they actually operate day-to-day, and, importantly, what their actual impact on systemic transformation is. Moreover, because our study relied mostly on website materials, it captures TCs’ rhetoric about themselves and their work, which may or may not overlap with what they actually do in practice, or how effective their efforts actually are, which can certainly be addressed in future research, e.g., through case analysis or participant observation. For the purpose of this paper, and also because most TCs that we identified are relatively new or in their early stages, we did not (and were not able to) collect detailed data on their hands-on practices. Thus, much more research is needed that looks at the actual practices of TCs in more detail and documents how TCs differ in how they work from the other catalytic entities discussed in the literature review section.