Sustaining Education with Mobile Learning for English for Specific Purposes (ESP): A Systematic Review (2012–2021)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Trends in ESP

1.2. Trends in Mobile Learning

1.3. Reviews on Mobile Learning

2. Methods

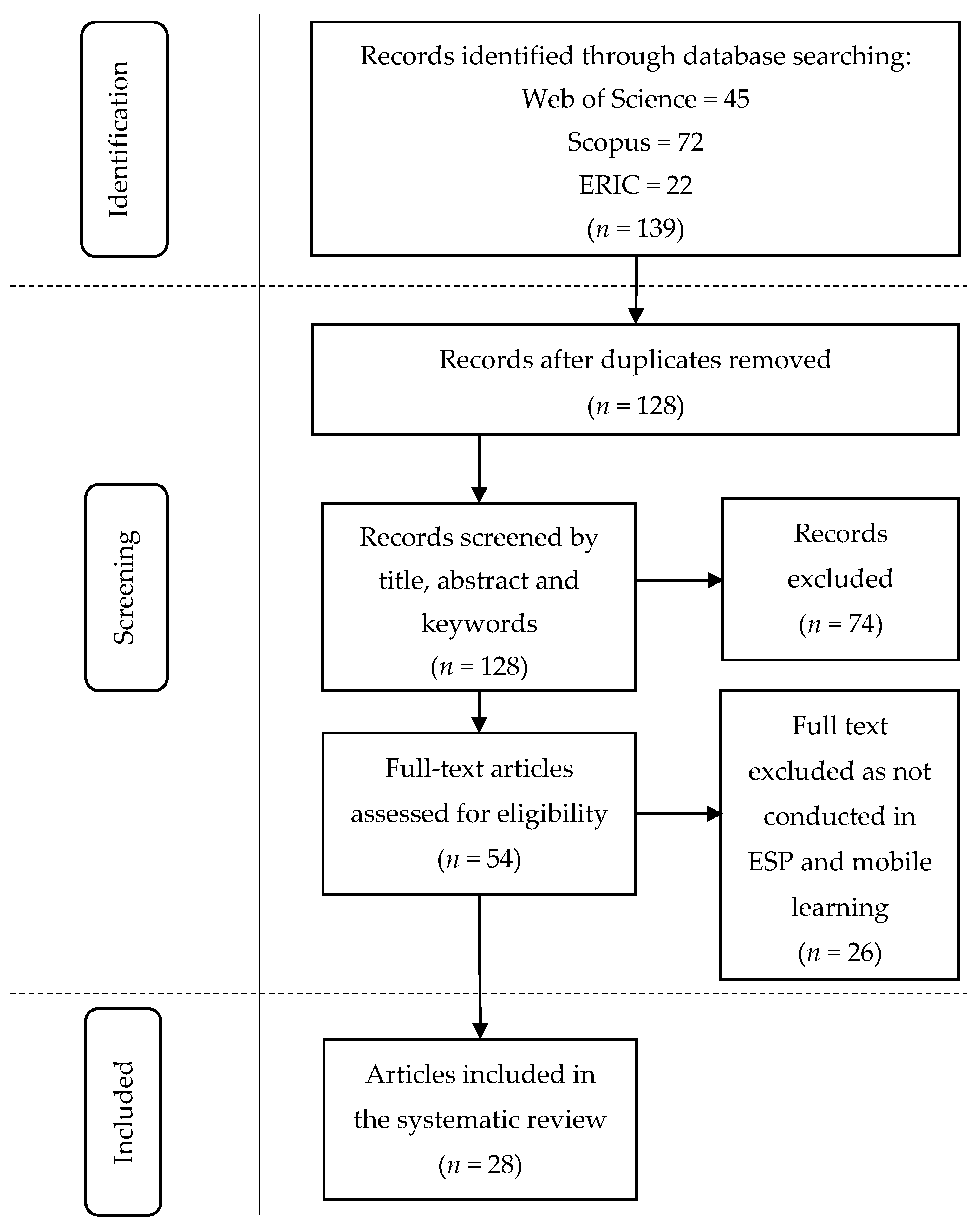

2.1. Identification

2.2. Screening

2.3. Included

2.4. Data Analysis Procedure

- (1)

- What are the types of platform used in mobile learning for ESP?

- (2)

- What are the language skills focused on mobile learning for ESP?

- (3)

- What are the field of studies involved in mobile learning for ESP?

3. Results

3.1. RQ1: What Are the Types of Platforms Used in Mobile Learning for ESP?

3.2. RQ2: What Are the Language Skills Focused on Mobile Learning for ESP?

3.3. RQ3: What Are the Field of Studies Focused on in Mobile Learning for ESP?

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosa, W. Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. In A New Era in Global Health: Nursing and the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Springer Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4 (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Ibnian, S.S.K. Writing Difficulties Encountered by Jordanian EFL Learners. Asian J. Humanit. Soc. Stud. 2017, 5, 2321–2799. [Google Scholar]

- Muhamad, N.; Rahmat, H. Investigating Challenges for Learning English through Songs. Eur. J. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2015, 6, 2321–2799. [Google Scholar]

- Misbah, N.H.; Mohamad, M.; Yunus, M.M.; Ya’acob, A. Identifying the Factors Contributing to Students’ Difficulties in the English Language Learning. Creat. Educ. 2017, 8, 1999–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaeva, S.; Synekop, O. Social Aspect of Student’s Language Learning Style in Differentiated ESP Instruction. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 8, 4224–4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajprasit, K.; Pratoomrat, P.; Wang, T. Perceptions and problems of english language and communication abilities: A final check on Thai engineering undergraduates. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2015, 8, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, T.; Waters, A. English for Specific Purposes: A Learning-Centred Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley-Evans, T.; John, M.-J.S. Developments in English for Specific Purposes: A Multi-Disciplinary Approach (Cambridge Language Teaching Library); Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, P. Choosing specialized vocabulary to teach with data-driven learning: An example from civil engineering. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2021, 61, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, K.R.M.; Hashim, H.; Yunus, M.M. MOOC for Training: How Far It Benefits Employees? J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1424, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, D. Some propositions about ESP. ESP J. 1983, 2, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaish, M.M.; Shuib, L.; Ghani, N.A.; Yadegaridehkordi, E.; Alaa, M. Mobile Learning for English Language Acquisition: Taxonomy, Challenges, and Recommendations. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 19033–19047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, M.; Aziz, A.A. Systematic Review: Approaches in Teaching Writing Skill in ESL Classrooms. Int. J. Acad. Res. Progress. Educ. Dev. 2019, 8, 450–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.M.; Yunus, M.M. Teachers’ Perception towards the Use of Quizizz in the Teaching and Learning of English: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biantoro, B. Exploring the Integrations of MALL into English Teaching and Learning for Indonesian EFL Students in Secondary Schools. Celt. A J. Cult. 2020, 7, 102–117. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Q.-K.; Hwang, G.-J. Trends in mobile technology-supported collaborative learning: A systematic review of journal publications from 2007 to 2016. Comput. Educ. 2018, 119, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacetl, J.; Klímová, B. Use of smartphone applications in english language learning—A challenge for foreign language education. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraj, P.M.I.; Klimova, B.; Habil, H. Use of Mobile Phones in Teaching English in Bangladesh: A Systematic Review (2010–2020). Sustainability 2021, 13, 5674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.S.E.M. ESP Needs Analysis: A Case Study of PEH Students. Sino-US Engl. Teach. 2016, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Izidi, R.; Zitouni, M. ESP Needs Analysis: The Case of Mechanical Engineering Students at the University of Sciences and Technology, Oran USTO. Rev. Académique Des Études Soc. Hum. 2017, 18, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, Z. A Study on Needs Analysis of Chinese Vocational Non-English-Majored Undergraduates in English for Specific Purposes. Open Access Libr. J. 2020, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Liu, Y. ‘Using all English is not always meaningful’: Stakeholders’ perspectives on the use of and attitudes towards translanguaging at a Chinese university. Lingua 2020, 247, 102959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravind, B.R.; Rajasekaran, V. A Qualitative Research through an Emerging Technique to Improve Vocabulary for ESL Learners. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 11, 441–446. [Google Scholar]

- Haniff, M.T.M.; Safinas, M.A.A.I.; Haimi, M.A.A.; Syafiq, Y.S.M.; Suzieanna, M.S.D. The Application of Visual Vocabulary for ESL Students’ Vocabulary Learning. Arab World Engl. J. 2020, 11, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solikhah, N.A. Improving Students’ Motivation in English Vocabulary Mastery through Mobile Learning. Wanastra J. Bhs. Dan Sastra 2020, 12, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrysh, Y.; Saienko, N. Teaching mediation skills at technology-enhanced ESP classes at technical universities. XLinguae 2020, 13, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafavi, S.; Mohseni, A.; Abbasian, G.R. The pedagogical efficacy of ESP courses for Iranian students of engineering from students’ and instructors’ perspectives. Asian-Pac. J. Second. Foreign Lang. Educ. 2021, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Montaner, S. EFL Written competence through twitter in mobile version at compulsory secondary education. Glob. J. Foreign Lang. Teach. 2020, 10, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, N.; Ebadi, S. Exploring learners’ grammatical development in mobile assisted language learning. Cogent Educ. 2019, 6, 1704599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.A.; Arshad, M.R.M. Investigating the perception of students regarding M-learning concept in Egyptian schools. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2017, 11, 112–122. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, B.; Roy, S.K.; Roy, F. Students Perception of Mobile Learning during COVID-19 in Bangladesh: University Student Perspective. Aquademia 2020, 4, ep20023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmila, R.M.R.; Harwati, H.; Melor, M.Y.; Helmi, N. iSPEAK: Using mobile-based online learning course to learn ‘English for the workplace’. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2020, 14, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.M.; Moghal, S.; Nader, M.; Usman, Z. The Application of Mobile Assisted Language Learning in Pakistani ESL classrooms: An Analysis of Teachers’ Voices. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang. 2020, 14, 170–197. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, S.K.; Khan, R.; Ahmed, P.R.I. Teachers’ and Students’ Perceptions towards Mobile-Assisted Language Learning (MALL) at Graduation Level. Int. J. Manag. 2020, 11, 1242–1260. [Google Scholar]

- Hafizah, M.K.; Nur-Ehsan, M.S. Education and Social Sciences Review The integration of mobile learning among ESL teachers to enhance vocabulary learning. Educ. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2020, 1, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Papadakis, S.; Kalogiannakis, M.; Zaranis, N. Educational apps from the Android Google Play for Greek preschoolers: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2018, 116, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Mkpojiogu, E.O.C.; Babalola, E.T. Using Mobile Educational Apps to Foster Work and Play in Learning: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2020, 14, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Hwang, G.-J. Roles and research trends of touchscreen mobile devices in early childhood education: Review of journal publications from 2010 to 2019 based on the technology-enhanced learning model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, H.J.; Boon, L.; Bartle, T. Does iPad use support learning in students aged 9–14 years? A systematic review. Aust. Educ. Res. 2020, 48, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.-F.; Hwang, G.-J. Trends and research issues of mobile learning studies in hospitality, leisure, sport and tourism education: A review of academic publications from 2002 to 2017. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 28, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- González-Albo, B.; Bordons, M. Articles vs. proceedings papers: Do they differ in research relevance and impact? A case study in the Library and Information Science field. J. Informetr. 2011, 5, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoven, D.; Palalas, A. Learner-Computer Interaction in Language Education: A Festschrift in Honor of Robert Fischer. CALICO J. 2013, 30, 137–165. [Google Scholar]

- Šimonová, I. Mobile-assisted ESP learning in technical education. J. Lang. Cult. Educ. 2015, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kirovska-Simjanoska, D. Mobile Phones as Learning and Organizational Tools in the ESP Classroom. J. Teach. Engl. Specif. Acad. Purp. 2017, 5, 321–332. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, R.-C. The Effect of English for Specific Purposes (ESP) Learning-Language Lab versus Mobile-Assisted Learning. Int. J. Distance Educ. Technol. 2017, 15, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikowski, D.; Casal, J.E. Interactive digital textbooks and engagement: A learning strategies framework. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2018, 22, 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson, C. Mobile and multidimensional: Flipping the Business English Classroom. J. Engl. Specif. Purp. Tert. Lev. 2018, 6, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghajani, M.; Adloo, M. The effect of online cooperative learning on students’ writing skills and attitudes through telegram application. Int. J. Instr. 2018, 11, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeeva, N.G.; Pavlova, E.B.; Zakirova, Y.L. M-learning in teaching ESP: Case study of ecology students. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 2019, 8, 920–930. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.G.; Miller, L. Improving English Learners’ Speaking through Mobile-assisted Peer Feedback. RELC J. 2020, 51, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivoruchko, V.A.; Raissova, A.B.; Makarikhina, I.M.; Yergazinova, G.D.; Kazhmuratova, B.R. Mobile-assisted learning as a condition for effective development of engineering students’ foreign language competence. Int. Educ. Stud. 2015, 8, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhezzi, F.; Al-Dousari, W. The Impact of Mobile Learning on ESP Learners’ Performance. J. Educ. Online 2016, 13, 73–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonova, I. Mobile devices in technical and engineering education with focus on ESP. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2016, 10, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, I. Discovering the Identity and Suitability of Electronic Learning Tools Students Use in English for Specific Purposes (ESP) Programs. CALL-EJ 2018, 19, 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson, L.E. Mobile-assisted learning and higher-education ESP: English for physiotherapy. Ling. Posnan. 2018, 60, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rajeswaran, C.M. Lack of Digital Competence: The Hump in a University-English for Specific Purpose Classroom. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2019, 8, 948–956. [Google Scholar]

- Balula, A.; Martins, C.; Costa, M.; Marques, F. Mobile Betting-Learning Business English Terminology using MALL. Teach. Engl. Technol. 2020, 20, 6–22. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhudair, R.Y. Mobile Assisted Language Learning in Saudi EFL Classrooms: Effectiveness, Perception, and Attitude. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2020, 10, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnke, L.; Ting, A. ESL students’ perceptions of mobile applications for discipline-specific vocabulary acquisition for academic purposes. Knowl. Manag. E-Learn. Int. J. 2021, 13, 102–117. [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi, A.S.; Meccawy, Z. Introducing Socrative as a Tool for Formative Assessment in Saudi EFL Classrooms. Arab World Engl. J. 2020, 11, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanjuntak, R.R. Learning Specific Academic Vocabulary using MALL: Experience from Computer Science Students. Teach. Engl. Technol. 2020, 20, 87–107. [Google Scholar]

- Tayan, B.M. Students and Teachers’ Perceptions into the Viability of Mobile Technology Implementation to Support Language Learning for First Year Business Students in a Middle Eastern University. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 2017, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Smith, C.; Kondo, M.; Akano, I.; Maher, K.; Wada, N. Development and use of an EFL reading practice application for an android tablet computer. Int. J. Mob. Blended Learn. 2014, 6, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczak, A. Using Memrise in legal English teaching. Stud. Log. Gramm. Rhetor. 2017, 49, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Batsila, M.A.; Tsihouridis, C.A.; Tsihouridis, A.H. ‘All for One and One for All’-Creating a mobile learning net for ESP students’ needs. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2017, 12, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Z.; Hwang, G.J.; Kuo, Y.L.; Lee, C.Y. Designing dynamic English: A creative reading system in a context-aware fitness centre using a smart phone and QR codes. Digit. Creat. 2014, 25, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Kitamura, S.; Shimada, N.; Utashiro, T.; Shigeta, K.; Yamaguch, E.; Harrison, R.; Yamauchi, Y.; Nakahara, J. Development and evaluation of English listening study materials for business people who use mobile devices: A case study. CALICO J. 2012, 29, 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svalina, V.; Ivić, V. Case Study of a Student with Disabilities in a Vocational School during the Period of Online Virtual Classes due to COVID-19. World J. Educ. 2020, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.M.I.; Radzuan, N.R.M.; Alkhunaizan, A.S.; Mustafa, G.; Khan, I. The efficacy of MALL instruction in business English learning. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2019, 13, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Revised Field of Science and Technology (FOS) Classification in the Frascati Manual. Dir. Sci. Technol. Ind. Comm. Sci. Technol. Policy 2007, 1–12. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/science/inno/38235147.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- Dolidze, T.; Doghonadze, N. Incorporating ICT for Authentic Materials Application in English for Specific Purposes Classroom at Higher Education Institutions. Int. J. Manag. Knowl. Learn. 2020, 9, 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, D.; Olizko, Y. Art and Esp Integration in Teaching Ukrainian Engineers. Adv. Educ. 2019, 6, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, F.K.M.; Zubir, N.Z.; Mohamad, M.; Yunus, M.M. Benefits and Challenges of Using Game-based Formative Assessment among Undergraduate Students. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2019, 7, 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorenko, S.; Kolomiiets, S.; Tikan, Y.; Tsepkalo, O. Interdisciplinary Approach to Modeling in Teaching English for Specific Purposes in the Ukrainian Context. Arab World Engl. J. Spec. Issue Engl. Ukr. Context 2020, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D.; Lin, Y.C. Mobile learning and student cognition: A systematic review of PK-12 research using Bloom’s Taxonomy. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 50, 684–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search String |

|---|---|

| Web of Science (WoS) | TS = ((“English for Specific Purpose *” OR “ESP” OR “English for Science and Technology” OR “English for STEM” OR “English for Business” OR “English for Social Study *”) AND (“mobile learn *” OR “mobile assisted language learning *” OR “mobile app *” OR “m-learning” OR “mobile device *”)) |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“English for Specific Purpose *” OR “ESP” OR “English for Science and Technology” OR “English for STEM” OR “English for Business” OR “English for Social Study *”) AND (“mobile learn *” OR “mobile assisted language learning *” OR “mobile app *” OR “m-learning” OR “mobile device *”)) |

| ERIC | English for Specific Purpose and mobile |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Studies conducted between 2012 and 2021 (10 year timespan) | Studies conducted before 2012 |

| Articles from journals | Conference proceedings, review articles, book chapters, reports |

| The text was written in English | Text not written in English |

| Related to mobile learning and English for Specific Purposes (ESP) | Not related to mobile learning and English for Specific Purposes (ESP) |

| Study | Database | Aim | Samples | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yamada et al. (2012) | WoS, Scopus | To verify the effectiveness of English language materials using mobile devices for business, in terms of the effect on motivation, overall learning performance, and practical performance in real business situations | 39 employees in sales (19) and non-sales (20) personnel | The audio materials distributed to respondents enhanced their listening skills and were closely related to their work context, which also improved their English for business operations. |

| Hoven & Palalas (2013) | WoS | To develop practical design principles for learning materials for students of English for specific purpose (ESP) | Business major undergraduates | The app enhanced learners’ listening skills aside from promoting cooperation and active learning among learners in specific contexts and flexibility for individual learning. |

| Liu, Hwang, Kuo & Lee (2014) | WoS, Scopus | Design and development of a context-aware ubiquitous learning (u-learning) system for users to increase fitness-related reading comprehension in a fitness centre | Customers in a fitness centre | The QR code app enhanced the customers’ Fitness English vocabulary and reading comprehension for exercise. |

| Šimonov (2015) | WoS | To identify the perceptions of technical and engineering students mobile-assisted instruction of English for specific purposes | 203 technical and engineering undergraduates | Online course and learning management systems through mobile learning encouraged specific learning activities and contents, which received positive acceptance by learners. |

| Batsila, Tsihouridis & Tsihouridis (2017) | WoS, Scopus | To identify the ways ESP teachers have employed mobile learning scenarios in the teaching of English to Vocational Secondary school learners | Six teachers and 157 vocational secondary students | Results showed that teachers use mobile learning to enhance students’ ESP because of its feasibility in catering to individuals’ needs. Students positively accept mobile learning because it’s easy and not biased towards language proficiency. |

| Kirovska-Simjanos (2017) | WoS | To show whether mobile phones used in the ESP classroom have the potential to help students learn more and grasp that knowledge | 10 ESP undergraduates from Computer Sciences and Technology programme | Results show that mobile learning encourages personalized learning, but could not replace a teacher’s role in the classroom. |

| Shih (2017) | WoS, Scopus, ERIC | To investigate the effects of teaching English for specific purposes (ESP) | 27 business major college students | Students had positive attitudes and were satisfied with using the mobile LINE app as a teaching and learning tool. |

| Bikowski & Casal (2018) | WoS, Scopus | To explore non-native English-speaking students’ learning processes and engagement as they use customized interactive digital textbooks on a mobile device | 13 fully matriculated undergraduates | Students had high expectations towards the digital textbook and positively accepted it, but reduced learning engagement. |

| Nickerson (2018) | WoS, Scopus | To give an account of an actual classroom experience of relevance for the teaching of English for Specific Business Purposes | 407 business major undergraduates | The findings showed that students learned at their own pace, making mobile learning flexible, convenient, and encouraging. |

| Aghajani & Adloo (2018) | WoS, Scopus | To examine the impact of Cooperative online learning via mobile applications on writing skills among Iranian intermediate ESP learners | 70 university ESP learner | Cooperative writing portrayed desirable results and scores through Telegram, and students were positive in using the app. |

| Valeeva, Pavlova & Zakirova (2019) | WoS, Scopus, ERIC | To investigate mobile learning of English for specific purposes to ecology students with the help of the Quizlet learning platform | 68 second-year undergraduates and 70 third-year undergraduates in ESP for ecology | Mobile learning increased the effectiveness of teaching ESP because it’s motivating and challenging. Mobile learning was satisfying for students because students were not segregated based on their proficiency levels. |

| Wu & Miller (2020) | WoS, Scopus, ERIC | To cast light on the use of mobile-assisted peer feedback to promote L2 speaking in English for Specific Purposes (ESP) course | 25 Business School undergraduates in an English for Specific Purposes course | Mobile-assisted peer feedback was positively accepted, though some limitations were highlighted, such as screen size and limited rubrics for feedback. |

| Krivoruchko et al. (2015) | Scopus | To identify the conditions for effective development of foreign language competence using technologically oriented methods of teaching a foreign language | 82 undergraduates from the engineering programme | Mobile learning encouraged an authentic learning environment, which provided opportunities for learning specific language terms. Mobile learning also improved the language competency of learners. |

| Alkhezzi & Al-Dousari (2016) | Scopus | To explore the impact of using a mobile application, namely Telegram Messenger, on teaching and learning English in an ESP context | 40 undergraduates at the Faculty of Allied Health Science | The results showed that learners’ vocabulary and reading comprehension improved. Learners also obtained technical vocabularies, but the grammar rules and writing skills did not show significant improvement. |

| Simonov (2016) | Scopus | To describe the state in mobile-assisted language learning (MALL) | 203 undergraduates in the Faculty of Informatics and Management | The mobile device owned by respondents were notebooks, and smartphones. Students used mobile devices for communication purposes, and respondents were optimistic about using mobile devices in teaching and learning. |

| Łuczak (2017) | Scopus | To investigate the students’ opinions about Memrise and to assess whether Memrise influences the test results achieved by the students during the legal English course | First, second and third-year undergraduates in B2+ legal English course. | Results showed that Memrise influenced the test results of learners positively. Their vocabularies in legal English improved due to the effective memorization revision in the mobile app. |

| Alizadeh (2018) | Scopus | To identify offline and online tools paramedical students use in the programs and investigate the purposes for and the conditions in which the tools are employed | 114 students taking the ESP courses at the school of Paramedical Sciences | Many respondents used Google Translate, but technical terms were not correctly translated. The tool lacked comprehensive and specific features for the field of study, in translating technical words from Persian to English. |

| Petterson (2018) | Scopus | To find out undergraduates’ attitudes towards the use of MALL in English for physiotherapy and anticipate whether possible drawbacks, such as cost, technological literacy, or storage capacity, would pose significant challenges for undergraduates | 15 undergraduates of English for physiotherapy course | The result showed that a majority of the students successfully learned anatomy words through the mobile app. A challenge was the cost of the app. A highly developed mobile app in a specific discipline for ESP is more effective than standard language learning apps. |

| Khan et al. (2019) | Scopus | To explore the potential usage of M-Learning in English for specific purpose (ESP) classes | 21 ESP undergraduates from College of Business Administration | Results showed that mobile learning improved learners’ proficiency in ESP due to ease of use. Mobile learning provided accessible materials. Mobile learning can be challenging due to Internet connection and screen size. |

| Rajeswaran (2019) | Scopus | To identify students‘ digital literacy, competence, and knowledge of digital tools and the latter‘s use in language learning and also to find how competent teachers are to facilitate language learning in the classroom with computers, mobile phones, and the Internet | 120 undergraduates from first-year Bachelor in Tech courses | The mobile phone was regarded as a helping tool, and participants agreed that the teacher’s role would not be replaced. Instead, mobile devices acted as a support. Students were well equipped with the technological knowledge to use mobile learning in the classroom. |

| Balula et al. (2020) | Scopus | To verify if mobile learning motivates learners and improves vocabulary acquisition, over three different academic years | 1st-year undergraduates enrolled in Management course | The results showed that students’ motivation increased with mobile learning, aside from improving their vocabulary acquisition. The app did not prove effective in improving the writing skill of students with the vocabulary gained. |

| Alkhudair (2020) | Scopus | To investigate the effectiveness of using m- learning or MALL in EFL classrooms and how the use of such an apparatus correlates with the learners’ academic achievements | 126 undergraduates from different Saudi universities | Results showed a significant relationship between hours of using mobile learning tools and high GPA achievement. Results also showed positive acceptance towards mobile learning. |

| Ishikawa (2014) | ERIC | To investigate the use of an English-language reading practice application for an Android tablet computer with students who are not native speakers of English | Students studying international affairs | Findings showed that students enjoyed reading with the app and their reading speed increased without losing comprehension ability. Plus, the app allowed students to possess a hard copy of the materials, which received positive feedback. |

| Tayan (2017) | ERIC | To investigate learners’ and teachers’ perceptions towards the proposed implementation of a MALL programme | 191 first-year undergraduates of Business English | Results showed that learners positively accepted mobile learning because learning could be scaffolded through a proper pedagogical mobile environment. Also, communication and motivation were highly increased through mobile learning, allowing collaboration and learner autonomy. |

| Saeed Alharbi & Meccawy (2020) | ERIC | To investigate the attitudes of EFL learners towards the use of mobile-based tests in English classes using Socrative as a model for assessment | 35 female students completed all three stages of the experiment: initial survey, Socrative quiz, post-experiment survey | Findings reported that almost half of the respondents preferred mobile-based tests due to advantages such as fun. |

| Svalina & Ivić (2020) | ERIC | To analyse the support that one student with disabilities receives in high school in English and German courses | One student with disabilities (Case study) | Results from the case study reported that the student loved learning English because of the mobile games used in this study. Online learning enhanced the students’ achievement. The student had difficulties with oral and written language but had good vocabulary and grammar |

| Simanjuntak (2020) | ERIC | To investigate the experiences of students in learning specific academic English vocabularies (ESAP) through the use of a mobile dictionary called SPEARA | 113 Computer Science undergraduates | With MALL, learning ESAP showed significant improvement. The students also perceived MALL as rewarding and positive, but it could not replace human interactions. |

| Kohnke & Ting (2021) | ERIC | To assess the perceptions of EAP undergraduates at an EMI university in Hong Kong regarding the use of an in-house app, Books vs. Brains@PolyU, for discipline-specific vocabulary learning | 16 first-year undergraduates | Findings from this study portrayed students’ positive views towards the app for learning specific English vocabularies. The app met the needs of students, who required different terminologies for different disciplines. |

| Type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Social Networking Sites (SNS) | Line app [46] Telegram app [49,53] |

| Learning Management System (LMS) | Blackboard Mobile Learn [44] Schoology [48] Edmodo [69] |

| Games | Quizlet [50] Socrative [58,61] |

| Assessment app | PeerEval (assessment site) [51] |

| Vocabulary app | Memrise [65] 3D Anatomical App [56] Mobile English Learn English on the go [43] Google Translate [55] Mobile dictionary SPEARA [62] Books vs. Brains@PolyU [60] |

| Reading app | Reading Practice App [64] Read with QR codes [67] Digital textbooks [47] |

| Listening app | Business English for sales department [68] |

| All four skills (listening, speaking, reading, writing) | Mobile app [52] |

| Not specified | [45,54,57,59,63,66,70] |

| Language Skills | Study |

|---|---|

| Listening | [68] |

| Speaking/Communication | [48,51] |

| Reading | [47,50,64,67] |

| Writing | [49] |

| Vocabulary | [43,55,56,58,60,62,65] |

| All skills (language competency) | [46,52,53,69] |

| Not specified (engagement and motivation) | [44,45,54,57,59,61,63,66,70] |

| Field | Programme/Course | Study |

|---|---|---|

| Social Science | Business | [43,46,47,48,51,58,60,63,68,70] |

| Law | [65] | |

| Linguistics and translation | [59] | |

| Administration | [61,64] | |

| Engineering and Technology | Engineering | [44,49,52,54] |

| Computer Science | [45,62] | |

| Technology | [57] | |

| Medical and Health | Allied Health Science | [53] |

| Medical | [55] | |

| Physiotherapy | [56] | |

| Fitness | [67] | |

| Natural Sciences | Ecology | [50] |

| Others | Vocational | [66,69] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rafiq, K.R.M.; Hashim, H.; Yunus, M.M. Sustaining Education with Mobile Learning for English for Specific Purposes (ESP): A Systematic Review (2012–2021). Sustainability 2021, 13, 9768. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179768

Rafiq KRM, Hashim H, Yunus MM. Sustaining Education with Mobile Learning for English for Specific Purposes (ESP): A Systematic Review (2012–2021). Sustainability. 2021; 13(17):9768. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179768

Chicago/Turabian StyleRafiq, Karmila Rafiqah M., Harwati Hashim, and Melor Md Yunus. 2021. "Sustaining Education with Mobile Learning for English for Specific Purposes (ESP): A Systematic Review (2012–2021)" Sustainability 13, no. 17: 9768. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179768

APA StyleRafiq, K. R. M., Hashim, H., & Yunus, M. M. (2021). Sustaining Education with Mobile Learning for English for Specific Purposes (ESP): A Systematic Review (2012–2021). Sustainability, 13(17), 9768. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179768