Uncovering Social Sustainability in Housing Systems through the Lens of Institutional Capital: A Study of Two Housing Alliances in Vienna, Austria

Abstract

:1. Introduction

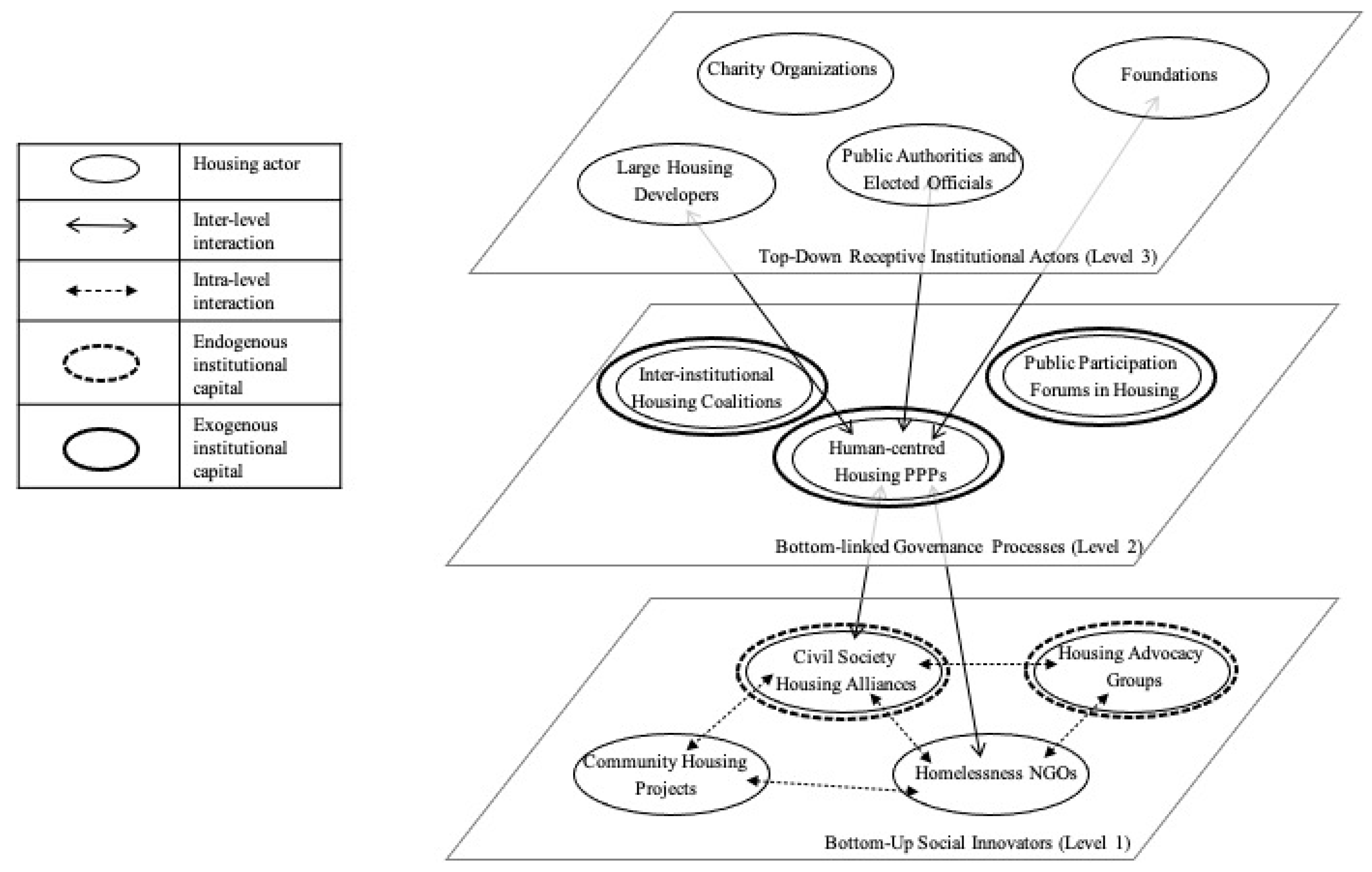

2. Methods

3. Uncovering the Conceptual Nexus between Bottom-Linked Governance and Institutional Capital in Housing Systems

4. Examining Civil Society Housing Alliances in Vienna, Austria

4.1. BAWO: An Alliance of Homelessness Service Providers

4.1.1. BAWO’s Endogenous Institutional Capital

4.1.2. BAWO’s Exogenous Institutional Capital: Genesis and Further Development

4.2. IGBW: An Alliance of Collaborative Housing Initiatives

4.2.1. IGBW’s Endogenous Institutional Capital

4.2.2. IGBW’s Exogenous Institutional Capital: Genesis and Further Development

5. Discussion and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Interviews | Type of Actor | Number of Interviews and Year | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014/15 | 2018 | 2020 | ||

| Leaders and members of housing alliances | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Institutional stakeholders | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Focus Groups | Type of Actor | Number of Interviews and Year | ||

| 2014/15 | 2018 | 2020 | ||

| Leaders and members of housing alliances | 1 | 1 | ||

| Illustrative websites consulted | Initiative Collaborative Building & Living, https://www.inigbw.org/die-initiative/english (accessed on 14 July 2021) BAWO—Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft Wohnungslosenhilfe, https://bawo.at (accessed on 14 July 2021) Wohnfonds_Wien, http://www.wohnfonds.wien.at/english_information (accessed on 14 July 2021) Baugruppen in Aspern/Vienna, http://aspern-baugruppen.at (accessed on 14 July 2021) FEANTSA, https://www.feantsa.org/en/resources/resources-database (accessed on 14 July 2021) | |||

| Illustrative secondary sources consulted | Temel et al. (2009), https://www.wohnbauforschung.at/index.php?id=340&lang_id=en (accessed on 14 July 2021) Gruber and Brandl (2014), https://www.inigbw.org/sites/default/files/literatur/2014-brandl_gruber-Projektbericht_Gemeinschaftliches_Wohnen_MA50wien_0.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2021) BAWO (2017) https://www.feantsa.org/download/bawo_2017_housing_for_all_longversion6629405791344905509.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2021) BAWO (2019) https://bawo.at/101/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Policy-Paper-English.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2021) | |||

| Total Number of Main Residency Dwellings | Tenure Type (in%, Rounded) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 912,100 | owner-occupancy | rental housing | other tenures | |||

| 19 | 77 | 4 | ||||

| Owner-occupied houses | Owner-occupied flats | Social rental housing | Privately rented flats | |||

| 6 | 13 | 44 | 33 | |||

| Municipal rental flats | Non-profit rental flats | |||||

| 23 | 21 | |||||

| Key Messages | Description |

|---|---|

| Problematizing the context | While acknowledging Austrian’s housing policy intention to serve a wide range of sections of the population and the existence of legal foundations that correspond to the government’s objective to provide adequate housing for all (see the ‘Tenancy Law’ and the ‘Limited-Profit Housing Act’), the paper problematizes the actual organization of the housing policy. The contrarieties in the systems lead to an insufficient supply of housing for low-income groups, as well as access barriers due to institutionalization dynamics and the exclusion of these groups in the allocation of subsidized apartments. |

| Housing for all: a way forward | The paper calls for adjustments in existing housing policy (especially rental market policy considering all three market segments: municipal housing, limited-profit housing and the private rental market), a closer cooperation between the housing and social sectors and a scale-up of specific and focused interventions (such as specific allocation systems and special living situations) to ensure that low-income people are reached in a better way and housing policies are organized according to a real focus on ‘Housing for all’. |

| Material and social criteria | Material criteria: Affordability; Housing Quality; Housing Stability; Location; Accessibility. Social criteria: Social inclusion; Professional Services; Prevention; Voluntariness and Accessibility; Discrimination and Stigmatization Avoidance. |

| Strategies and actions | 1. Strengthen the rental market 2. Make the tenancy law tenant-friendly again 3. Preserve and expand limited-profit housing 4. Improve the access to limited-profit housing 5. Make better use of occupancy rights 6. Expand municipal housing and ensure its accessibility 7. Encourage the usage of vacant apartments 8. Stimulate needs-based housing development 9. Make use of instruments in the zoning law towards affordable housing 10. Steps towards incomes that are sufficient to secure a livelihood 11. Standardize and increase financial benefits towards housing |

| Key Messages | Description |

|---|---|

| New voices from the network | UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing; The Association for Housing Subsidies; Vienna University of Technology; Viennese Advisory Service for Homeless Assistance; Tenants’ Association of Austria; Architect, Town Planner and Activist; Vorarlberg State Government Office; Vienna Housing Service; EBG; Federal Ministry of Labor, Social Affairs, Health and Consumer Protection; Austrian Anti-Poverty Network; University of Vienna; Austrian Federation of Limited-Profit Housing Associations (GBVs); Central Bank of Austria; FEANTSA; Housing-Construction-Policy Forum; University of Applied Sciences Upper Austria; Statistics Austria; Vienna Chamber of Labor; European Citizens’ Initiative). |

| Problematization of the context | The paper acknowledges the fact that the Austrian housing system has been cited as a best-practice example internationally and that housing quality has improved substantially over the years. However, the paper argues that indicators such as cost increases (particularly rising sharply over the past two decades), the lack of ratification of paragraphs 30 and 31 of the European Social Charter, which refer to poverty, social exclusion and housing, the lack of a permanent housing prospect bound by tenancy law and the availability and (over)use of homeless assistance services over time, show that housing in Austria has once again become a socio-political challenge and more efforts will be needed to secure an individually enforceable right to housing (BAWO Chair and UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing). |

| Housing First promotion | Access to a permanent tenancy—also in expensive/gentrified areas—is a starting point for social participation and integration of homeless people in their local community. Housing also has a destigmatizing effect and promotes independent living. |

| Policies and Demands | 1. Implement the human right to housing 2. Strengthen the rental sector 3. Lower housing costs and effectively limit profits earned through letting residential properties 4. Strengthen the legal framework for sustainable housing 5. Ensure non-discriminatory and inclusive access 6. Create more affordable, permanent and inclusive housing 7. Establish measures for a living wage 8. Strengthen the social security system through social security funds 9. Implement vital social assistance benefits at Federal and State level 10. Standardize and increase monetary benefits for housing 11. Improve stability and quality of life through a good home environment 12. Expand Housing First and other mobile support services |

| Comparing the Two Alliances in Terms of… | BAWO | IGBW |

|---|---|---|

| Membership | Small | Small |

| Financial resources | Limited | Limited |

| Geography of action/initiatives | Austria-wide | Mostly Vienna-focused |

| Type of housing program | Affordable housing, Housing First | Collaborative housing (incl. CoHousing, Baugruppen) |

| Populaton targeted | Homeless, ethnic communities, elderly, youth | Middle class Austrians interested in community living |

| Promotion of resident involvement | Emphasis in their policy papers on people’s participation in the designing process of their houses and neighborhoods as well as the creation and attractiveness of shared facilities for people to meet and interact | Emphasis in their housing projects on residents’ participation and creation and use of community spaces |

| Endogeous instutitional capital | Knowledge exchange among members, awareness-raising within the sector, advocacy strategy design | Knowledge exchange among members, awareness-raising mainly outside the sector, advocacy strategy design |

| Exogenous institutional capital | Inter-institutional coalition building, expansion and/or consolidation of partnerships with institutional actors, policy experimentation | Expansion and/or consolidation of partnerships with institutional actors, policy experimentation |

References

- Boström, M. A missing pillar? Challenges in theorizing and practicing social sustainability: Introduction to the special issue. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2012, 8, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A.; Parra, C. Social innovation in an unsustainable world. In The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research; Moulaert, F., MacCallum, D., Mehmood, A., Hamdouch, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi, M.R.; Keivani, R. Critical reflections on the theory and practice of social sustainability in the built environment—A meta-analysis. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 1526–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lang, R. Social sustainability and collaborative housing: Lessons from an international comparative study. In Urban Social Sustainability; Shirazi, M.R., Keivani, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 193–215. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, C. Social sustainability: A competitive concept for social innovation? In The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research; Moulaert, F., MacCallum, D., Mehmood, A., Hamdouch, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 142–154. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, C.; Moulaert, F. Why sustainability is so fragilely ‘social’. In Strategic Spatial Projects: Catalysts for Change; Oosterlynck, S., Van den Broeck, J., Albrechts, L., Moulaert, F., Verhetsel, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, C. Sustainability and multi-level governance of territories classified as protected areas in France: The Morvan regional park case. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2010, 53, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.; Pradel, M. Bottom-linked approach to social innovation governance. In Social Innovation as Political Transformation; Van den Broeck, P., Mehmood, A., Paidakaki, A., Parra, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 97–98. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.; Haddock, S.V. Housing and community needs and social innovation responses in times of crisis. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2016, 31, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paidakaki, A.; Moulaert, F.; Leinfelder, H.; Van den Broeck, P. Can pro-equity hybrid governance shape an egalitarian city? Lessons from post-Katrina New Orleans. Territ. Politics Gov. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paidakaki, A.; Parra, C. “Housing for all” at the era of financialization; can (post-disaster) cities become truly socially resilient and egalitarian? Local Environ. 2018, 23, 1023–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizaguirre, S.; Parés, M. Communities making social change from below. Social innovation and democratic leadership in two disenfranchised neighbourhoods in Barcelona. Urban Res. Pract. 2019, 12, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizaguirre, S.; Pradel, M.; Terrones, A.; Martinez-Celorrio, X.; García, M. Multilevel governance and social cohesion: Bringing back conflict in citizenship practices. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 1999–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizaguirre, S.; Pradel-Miquel, M.; García, M. Citizenship practices and democratic governance: ‘Barcelona en Comú’ as an urban citizenship confluence promoting a new policy agenda. Citizsh. Stud. 2017, 21, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galego, D.; Moulaert, F.; Brans, M.; Santinha, G. Social innovation & governance: A scoping review. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2021, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.; Eizaguirre, S.; Pradel, M. Social innovation and creativity in cities: A socially inclusive governance approach in two peripheral spaces of Barcelona. City Cult. Soc. 2015, 6, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moulaert, F.; MacCallum, D. Advanced Introduction to Social Innovation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moulaert, F.; MacCallum, D.; Mehmood, A.; Hamdouch, A. (Eds.) The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; Available online: https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/usd/the-international-handbook-on-social-innovation-9781782545590.html (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Moulaert, F.; MacCallum, D.; Van den Broeck, P.; Garcia, M. Bottom-linked Governance and Socially Innovative Political Transformation. In Atlas of Social Innovation. Second Volume: A World of New Practices; Howaldt, J., Kaletka, C., Schröder, A., Zirngiebl, M., Eds.; Oekoem Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2019; pp. 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Paidakaki, A. Social Innovation in the Times of a European Twofold Refugee-Housing Crisis. Evidence from the Homelessness Sector. Eur. J. Homelessness 2021, 15, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pradel-Miquel, M. Analysing the role of citizens in urban regeneration: Bottom-linked initiatives in Barcelona. Urban Res. Pract. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Building institutional capacity through collaborative approaches to urban planning. Environ. Plan. A 1998, 30, 1531–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Institutionalist analysis, communicative planning, and shaping places. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1999, 19, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P.; De Magalhaes, C.; Madanipour, A. Place, identity and local politics: Analysing initiatives in deliberative governance. In Deliberative Policy Analysis: Understanding Governance in the Network Society; Maarten, A., Hajer, M.A., Wagenaar, H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, A.; Smallman, C.; Tsoukas, H.; Van de Ven, A.H. Process studies of change in organization and management: Unveiling temporality, activity, and flow. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gibbert, M.; Ruigrok, W.; Wicki, B. What passes as a rigorous case study? Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research. Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Moulaert, F.; Cabaret, K. Planning, networks and power relations: Is democratic planning under capitalism possible? Plan. Theory 2006, 5, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.R. The challenge of strengthening nonprofits and civil society. Public Adm. Rev. 2008, 68, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Thrift, N. Globalization, Institutions, and Regional Development in Europe; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jenks, M.; Jones, C. Dimensions of the Sustainable City; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Novy, A. Unequal diversity—On the political economy of social cohesion in Vienna. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2011, 18, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.; Stoeger, H. The role of the local institutional context in understanding collaborative housing models: Empirical evidence from Austria. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2018, 18, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, R.; Huber, M. Die Sicherung der “Sozialen Nachhaltigkeit” im Zweistufigen Bauträgerwettbewerb: Evaluierung der Soziologischen Aspekte—Eine Zwischenbilanz Vienna: Wohnbund: Consult. Available online: http://www.wohnbauforschung.at/index.php?idD432 (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Mundt, A.; Amann, W. “Wiener Wohnbauinitiative”—A new financing vehicle for affordable housing in Vienna, Austria. In Affordable Housing Governance and Finance: Innovations, Partnerships and Comparative Perspectives; van Bortel, G., Gruis, V., Nieuwenhuijzen, J., Pluijmers, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 187–208. [Google Scholar]

- Tamesberger, J.; Bacher, H.; Stöger, H. Die Wirkung des sozialen Wohnbaus in Österreich. Ein Bundesländervergleich. WISO 2019, 42, 29–58. [Google Scholar]

- Statistik Austria. Wohnen 2019—Mikrozensus—Wohnungserhebung und EU-SILC; Statistik Austria: Vienna, Austria, 2020; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Aigner, A. Housing entry pathways of refugees in Vienna, a city of social housing. Hous. Stud. 2019, 34, 779–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEANTSA. Fifth Overview of Housing Exclusion in Europe; FEANTSA: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kadi, J. Recommodifying Housing in Formerly “Red” Vienna? Hous. Theory Soc. 2015, 32, 247–265. [Google Scholar]

- BAWO. Housing for All Affordable. Permanent. Inclusive. Available online: https://www.feantsa.org/download/bawo_2017_housing_for_all_longversion6629405791344905509.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- FEANTSA. Third Overview of Housing Exclusion in Europe; FEANTSA: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, E.; Lang, R. Collaborative housing models in Vienna through the lens of social innovation. In Affordable Housing Governance and Finance: Innovations, Partnerships and Comparative Perspectives; van Bortel, G., Gruis, V., Nieuwenhuijzen, J., Pluijmers, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- National Strategies to Fight Homelessness and Housing Exclusion: Austria. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/search.jsp?advSearchKey=espn+thematic+report&mode=advancedSubmit&langId=en (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- FEANTSA. News: BAWO Policy Paper Proposes Eleven Measures to Improve the Housing Situation in Austria. Available online: https://www.feantsa.org/en/news/2018/01/17/bawo-policy-paper-proposes-11-measures-to-improve-the-housing-situation-in-austria?bcParent=27 (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- BAWO. Housing for All Affordable Permanent Inclusive. Available online: https://bawo.at/101/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Policy-Paper-English.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- IGBW. Initiative Gemeinsam Bauen & Wohnen (Initiative Collaborative Building & Living). Available online: https://www.inigbw.org/die-initiative/english (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Czischke, D.; Carriou, C.; Lang, R. Collaborative Housing in Europe: Conceptualizing the field. Hous. Theory Soc. 2020, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, R.; Lorbek, M.; Ptaszyńska, A.; Wittinger, D. Baugemeinschaften in Wien: Endbericht 1, Potenzialabschätzung und Rahmenbedingungen; City of Vienna: Vienna, Austria, 2009; Available online: https://www.wohnbauforschung.at/index.php?id=340&lang_id=en (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Jezierska, K.; Polanska, D.V. Social movements seen as radical political actors: The case of the Polish Tenants’ movement. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2017, 29, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mullins, D.; Moore, T. Self-organised and civil society participation in housing provision. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2018, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.; Mullins, D. Field emergence in civil society: A theoretical framework and its application to community-led housing organisations in England. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2020, 31, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Droste, C. German Co-Housing: An Opportunity for Municipalities to Foster Socially Inclusive Urban Development? Urban Res. Pract. 2015, 8, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paidakaki, A.; Lang, R. Uncovering Social Sustainability in Housing Systems through the Lens of Institutional Capital: A Study of Two Housing Alliances in Vienna, Austria. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179726

Paidakaki A, Lang R. Uncovering Social Sustainability in Housing Systems through the Lens of Institutional Capital: A Study of Two Housing Alliances in Vienna, Austria. Sustainability. 2021; 13(17):9726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179726

Chicago/Turabian StylePaidakaki, Angeliki, and Richard Lang. 2021. "Uncovering Social Sustainability in Housing Systems through the Lens of Institutional Capital: A Study of Two Housing Alliances in Vienna, Austria" Sustainability 13, no. 17: 9726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179726

APA StylePaidakaki, A., & Lang, R. (2021). Uncovering Social Sustainability in Housing Systems through the Lens of Institutional Capital: A Study of Two Housing Alliances in Vienna, Austria. Sustainability, 13(17), 9726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179726