Abstract

Recent scholarship on urban social sustainability has redirected its attention to the role of place-based theories and practices in achieving and sustaining social outcomes. The notion of place and its centrality in everyday life of urban citizens could be used as an anchor point to study urbanisation processes and rapid urban changes. This paper employs a place-based framework of urban social sustainability in parallel to a framework of ‘place transformation’ to examine the consequences of soft densification on place attachment at the neighbourhood level in Tehran, Iran. Through analysing sixteen semi-structured interviews with residents, this paper argues that the temporal element of soft densification makes it a place undermining process, eradicating individual and collective place memory through resetting the time of the place. Moreover, the findings highlighted parallel trajectories in the meanings associated to place by residents which underscore the contradiction between ‘lived space’ and ‘conceived space’. Furthermore, it was found that loss of place attachment due to urban densification commonly leads to passive modes of response such changing lifestyle and daily routines, and voluntary relocating to adapt to the new socio-spatial order.

1. Introduction

The growing debates on the social dimension of sustainable development and its relevance to urban settings have recently witnessed a surge in the literature calling for a relational approach to urban social sustainability which is sensitive to contextual specificities and place-based dynamics at the local level [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Within this trend, there is a renewed attention to the notion of place and its centrality in everyday life of urban citizens; an attribute which could be used as an anchor point to study social outcomes of urbanisation processes [10,11,12,13]. Place is present in these debates not as the physical setting of the cities but as the encompassing element incorporating social relations, personal meanings and experiences [14,15,16]. The shift of attention to the local level and to the place-based theorisation of social sustainability points to the pressing need for re-framing the unit of the neighbourhood as a ‘place’ [7,17,18,19] where ‘being-in-the-world’ [20] can be practiced. The neighbourhood is a unit of praxis and is capable of reconstructing consciousness and communal sensibilities. If coordinated horizontally and re-defined progressively [21], the ideas of place and neighbourhood attachment could mobilise social alliances and calls for urban justice.

The theoretical framing of this research is based on the idea of situated or emplaced social sustainability which accentuates the role of place and the attributes of person-place relationships in promoting and maintaining urban social sustainability at the neighbourhood level. It employs a framework of ‘place transformation’ [5] to examine the consequences of soft densification on place attachment as an indicator of urban social sustainability [22]. The contextual focus of this research is limited to a residential neighbourhood typology in Tehran, Iran which has been prone to systematic soft densification in the past decades and is physically characterized by its gridiron street network and row apartment blocks. Soft densification refers to small-scaled and incremental developments on the threshold of formal planning frameworks which are undertaken by individual owners and local developers [23]. The three underlying dimensions of soft densification encompassing its temporality, its politico-governance indeterminacy and its economically driven and speculative nature are all recognisable in Tehran [24,25]. As its main objective, this article aims to explore the intersection between urban social sustainability, place (un)making and (quasi)formal urban planning practices in Tehran. The article asks how soft densification impacts the construct of place and people-place relationships in an urban setting. It also aims to elaborate on the interaction between these cores and the ways this interplay can create alienated citizens.

This paper sheds light on the complex dynamics of the relationship between the experience of soft densificaiton and place change. It specifically elaborates on the inherent temporality of densification processes, the differentiated response patterns to place change by the residents, and the polito-economic drivers and determinants of density and place change. The results underline the critical role of place-based politics and theorisation in promoting urban social sustainability. The paper puts forward the view that urban social sustainability is contingent on the particular social conditions of place. It also argus for a reformulation of place-based politics through consolidating the progressive potentialities of the notion of place in instigating socio-political change. Furthermore, this article provides an in-depth, local-level and exclusively contextual knowledge of a critical and ongoing case of soft densification in Tehran. Following what Roy calls ‘the paradoxical combination of specificity and generelasability’ [26], this paper argues that the acquired situated and emplaced knowledge can be appropriated and used in different settings in both global North and South. The insights emerged from this research will have policy implications for urban governance and development plans by shifting the attention towards the level of everyday life and emancipating social sustainability discourse and practice from theoretical ambiguities and equivocations.

The paper is structured in the following order. First, it critically evaluates the use of place as a concept and place transformation as a process of urban change. It then explores the recent trend in the literature to focus on place-based theorisation of urban social sustainability. The paper then introduces the case of soft densification in Tehran and presents some empirical evidence on the construct of place meaning in Tehran and the different modes of reaction to place change. Lastly, it offers conclusions on the politics of place in relation to urban social sustainability and provides implications for future research.

2. Framework

The significance of place on human experience is underlined in a notable branch of place literature [16,27,28,29,30,31]. ‘Place’ is the setting where the social and physical realms of everyday life converge, “a meaningful location … [that] people are attached to in one way or another” [16] (p. 7). The relationship between place and people as its users is reciprocal; what makes place different from space is the human experience of it, while on the other hand, to be is to be in place [32]. The way people attach to a place, assign meanings to it and experience it is an insightful source of knowledge to understand how urban transformation influences the multiple aspects of everyday life of the residents at the local level. Place is also explained as a reiterative social practice or event, marked by openness and change rather than boundedness and permanence [33]. Malpas emphasises on the critical role of place in human experience and contends that existence is always being in place [14]. Place can be framed as a dynamic and relational concept encompassing physical objects, social relations and the events happening in a given place [14]. Place as a location, however, is deemed to be a limiting and inconclusive proposition, incapable of explaining the fluidity and dynamism of place [34].

The idea of place as a dynamic entity goes against the ontological readings of the concept based on authenticity; readings that are the main culprits of the retreat of place into reactionary politics [35]. Fluidity and dynamism of place are critical features that need to be accounted for in order to holistically reflect on the process of place creation. Within the dynamic process of shaping place, both social and physical domains are in constant change through various trajectories such as migration, demographic shifts, regeneration and redevelopment, and as an extreme case, through natural or man-made disasters. Therefore, a holistic approach to place defines it as neither a mere physical location or locale, nor just a social construct; instead, place in a complex phenomenon, shaped by the socio-spatial dialectic [36] where the social, as much as the physical, is involved in its formation.

From another perspective, place exists at multiple temporal and spatial scales and holds dissimilar elements together. In other words, place is a fruitful paradox of containment and liberation [29] and it is this liberating aspect of place that requires further elaboration and revival. As Casey states, “to live is to live locally, and to know is … to know the places one is in” [37] (p. 18). Particularity of each place and conscious emplacement are conditions that could contribute to creation and strengthening of what Massey has called progressive sense of place [21]. Against ‘defensive localisation’ [38] and the reactionary politics of place which lead to exclusionary outcomes, Massey introduces a sense of place that is not self-closing and defensive but outward looking [21]. The progressive sense of place is premised on distinctiveness of places while simultaneously highlighting the possibilities of becoming something new and instigating social and political change at the local level. The progressive idea of place necessitates seeing place as a process and site of multiple identities and histories, in interaction with other places [21]. Despite the theoretical complexities of place, the concept is still highly relevant in explicating and signifying the grounded experience of a bounded location, however unstable and permeable [38].

Place as a process is tightly associated with ‘change’. According to Lynch “a change in environment may be a growth or a decay, a simple redistribution, an alteration in intensity, an alteration in form. It may be a disturbance followed by a restoration, an adaptation to new forces, a willed change, and uncontrolled one.” [39] (p. 190). Change could take many shapes and pathways, both positive and negative, and accordingly, the responses and reactions of an environment’s user to change could differ significantly. The six interconnected processes of place change suggested by Seamon—place interaction, place identity, place release, place realisation, place creation, and place intensification [40]—are the underlying routes of urban transformation that influence, and are influenced by, the social and physical setting of cities. The first four processes explain what places are and how they work, while the last two processes are concerned about how positive or negative/inappropriate human efforts can either improve places or push them towards decline. Among these, place intensification corresponds more concretely to urban densification. Place intensification is a process of place change, highlighting the independent power of policy, design and fabrication [40]. Intensification can either be constructive by contributing to a place becoming more durable; or undermining through poorly conceived designs, policies and constructions. To complement Seamon’s articulation of place intensification processes, this paper also employs the theoretical model put forward by Devine-Wright which uses social representation theory to elucidate on the different stages of psychological response to the built environment change [10]. Devine-Wright suggested five stages of responding to place change including becoming aware, interpreting, evaluating, coping and acting. The bottom-line objective of the above theoretical framing of place change is to reiterate that any place change, including place intensification, could be interpreted, evaluated and coped with in multiple ways by the users of place. The way an individual reacts to place change conveys significant information about his/her relationship with place.

A complementary theoretical lens that could be applied to the investigations of urban transformation is urban social sustainability [22,41,42]. Social sustainability was once outlined as the under-theorised and poorly-examined dimension of sustainable development [43,44]. The past decades however have witnessed a surge in studies trying to theorise, evaluate and operationalise social sustainability in multiple scales and from various disciplinary views [7,8,45,46,47]. A recent trend in the literature on urban social sustainability has rightly and timely underlined the relational nature of social indicators and objectives. Shirazi and Keivani have proposed a tripartite framework encompassing three dimensions as neighbourhood—conceived qualities, or hard infrastructure-, neighbouring —perceived qualities, or soft infrastructure-, and neighbours—neighbourhood residents, population profile [48]. From another perspective but based on similar premises, Seghezzo has proposed a social sustainability model based on three elements of place, permanence and person [49]. Social sustainability in the urban context always unfolds and takes shape in real places [29] and is grounded in place. This proposition essentially means that the social indicators enumerated in urban social sustainability discussion are relational. It could be argued that urban social sustainability is, at an abstract level, concerned with place and the people-place relations. It is place itself at the centre of the whole discussions of creating sustainable environments and ensuring their endurance. Furthermore, people-place relations and their dynamics determine whether a community is socially sustainable. Urban social sustainability thus means different things to different groups of people and communities [50]. At the same time, urban social sustainability signifies a dialectical character [51]; it is simultaneously concerned with physical and non-physical qualities; qualities that are both objective and subjective, conceived and perceived, quantitative and qualitative. A socially sustainable environment is a locality where both physical and non-physical qualities are positively perceived, highly valued and exercised/utilised for a considerable period of time [42].

In addition to the place-centred framework, urban social sustainability could also be theorised based on its politics of implementation. Sustainability is described as the “dominant ideological guise of the capitalist system of production” [52] (p. 235). The main charge against sustainability is that it has failed mobilisation towards political change. Without clear political content, the utility of social sustainability concept might be well in doubt [53]. The current literature on social sustainability fails to acknowledge the complexity of local political concept and does not acknowledge the constraints to participation, such as political environment [50]. It is argued that as an ideological construct, sustainable development obscures particular struggles at the local level [52]. Concerning social sustainability, the question of ‘What is to be sustained?’ is still bound with much controversy and ambiguity. Whether it is the status quo that needs to be sustained or it is the forward-looking movement towards achieving socially positive outcomes that must be strengthened and sustained is a matter of controversy and wholly reflects the articulated chaotic state of the social sustainability literature [54]. Furthermore, to make social sustainability a useful concept it must be linked to democracy [53]; not to the surface value of democracy as a representational mechanism of governance or ‘consensus democracy’ but to its inherent logic as equality [55]. The democratic and political theorisation of social sustainability will be able to apply the universal claims within the particular struggles because it is only at the level of particular that the concerns of democracy can be mobilised [53].

Within the discussions of urban social sustainability, the idea of place offers an alternative epistemology [29] which combines praxis with sustainability and constructs a setting of collective inquiry and resistance. Sustainability as a place-based discourse stands against the prevalent developmental framework. The highly debated and widely advocated idea of ‘sustainable development’ as we see abundantly in policy documents and visionary plans, is oxymoron. In the urban setting, it is the political economy of change that determines what should be sustained and for whom the benefits of sustainability agenda should be yielded. The widespread discussion on the sustainability of building denser cities should be substituted by place-based discourses, asking the more fundamental question of the political and economic drivers of densification and, in general, urbanisation as the dominant mode of life in our time.

There is a growing interest within urban studies in reformulation and recognition of the potentialities of the neighbourhood unit for social theory, while acknowledging its fluid spatial, functional, and political boundaries [56,57]. These studies have stressed the significance of neighbourhood as a social construct and the central setting for living, working, socialising, and practicing social life [7]. There is also a similar interest in studying social sustainability at the neighbourhood level for practical concerns, relevance to the everyday life of the residents, and potentials for effective application and improvement [42]. Although neighbourhood as a bounded spatial unit has been portrayed as incompatible with the condition of planetary urbanisation and thus is relevance in urban research has been critically questioned [58], this paper argues that making an analogy between neighbourhood and place—in its relational, unbounded, and progressive definition—will overcome the raised theoretical deficiency and irrelevance of neighbourhood and more importantly, would bridge the gap between research and policy in urban social sustainability. The idea of neighbourhood—fluid or bounded—has the potential of linking urban social sustainability objectives and aspirations with more fundamental social and political calls for change.

Despite all the theoretical and empirical efforts to explicate the ideas of sustainable development and social sustainability, several ambiguities and contesting viewpoints exist regarding their real objectives and application within the capitalist system [42]. A pathological approach to the current status and the developmental pathway of urban social sustainability debates suggests the need to democratise and politicise the utility of social sustainability by focusing on particular struggles at the local level; developing an emplaced and situated framework of utilisation of urban social sustainability at the neighbourhood. The convergence of a progressive idea of place with a place-based theorisation of urban social sustainability will release the unrealised potentials of both place scholarship and social sustainability of neighbourhoods.

This paper takes urban social sustainability as a relative, place-based and locally rooted concept and argues that a detailed study of people-place relationships could provide an indication of social sustainability in a neighbourhood and also, could open up new avenues towards more progressive politics of place and sustainability. Place attachment pronounces the significance of place [22,59,60,61]. The imperative role of place attachment in achieving social sustainability is more evident at the relatively smaller geographic units such as neighbourhood where people have more direct engagement with their surrounding area. The argument is that by establishing meaningful bonds and links to their living environment, people would be able to effectively involve in their community, establish social and kinship bonds, actively engage in decision-making, be reflective to changes and thus, positively contribute to social sustainability of their living environment [62]. Place attachment has been subject to many studies particularly in the fields of human geography [16,32,63] and environmental psychology [30,59,64,65,66]. In the simplest terms, place attachment refers to the affective bond between people and their surrounding built environment [67]. In a prominent theoretical model of place attachment, the concept is delineated as a tripartite phenomenon, constituted of person, place and process dimensions [66]. Place attachment in this theorisation is based on the idea of place as a process. Changes in place attachment are thus not exclusively a result of variations in individuals’ connection with place but also result out of place transformation [29]. The present paper also argues that urban transformation could be seen as a process of effacing both material landscape and communal associations within the place. Therefore, a potential outcome of urban transformation could be the creation of placeless and sterile urban environments.

3. Research Context and Methods

With a population of around 8.7 million in 2016, Tehran is considered as the second-largest city in the Middle East—in terms of metropolitan area population [68]. Throughout its history, Tehran has undergone massive transformation and expansion both in terms of its demographic profile and its physical urban landscape [69,70,71]. Nevertheless, the city’s morphological transformation through time has been scarcely studied [72,73]. A critical element of the ongoing process of urban change in Tehran is the process of soft densification. Examining the various ways through which urban densification unfolds in the cities uncovers two prominent modes, namely hard and soft densification [23]. Hard densification refers to large scale developments undertaken by property developers as external actors and unfolded within the boundaries of official planning frameworks. Soft densification on the other hand refers to small-scaled, incremental, local-level developments undertaken by individual owners, local developers and any actor with sufficient capital to initiate the construction process. Soft densification unfolds on the threshold of formal planning frameworks and in most cases, does not follow the official planning narratives [23,74]. As an in-fill type of development, soft densification takes various forms of spatial reorganisation through subdivision, consolidation, plot-base rebuilding, extension or roof stacking. Within the rigidly defined planning frameworks of the western European cities, soft densification mostly occurs in peri-urban regions where the line between formal planning regulations and informal, private-led micro developments becomes blurry [75]. In these contexts—e.g., fast-growing cities of the global South—where planning regimes are not structured around strong regulatory frameworks and robust control mechanisms, soft densification could also be materialised in inner-city neighbourhoods. The empirical evidence suggests that the challenge of soft densification for the southern cities lies on the intersection of the unplannable planning regime [76] and the place attributes and qualities [77,78]. The incremental, plot-based, mostly informal, piecemeal and fragmented changes in place are difficult to regulate and monitor and often occur simultaneously across a wide geography [74]; however, considering the scale of soft densification in cities such as Tehran, the accumulative impact of these minor changes through time become considerable and have huge implications for urban everyday life, access to services and place qualities.

Soft densification in Tehran is facilitated by three key drivers: Lack of well-regulated and reinforced administration in the planning system; migration and population increase; and profitability of residential redevelopment and prevalence of property speculation [79,80,81,82]. Densification has become one of the most contentious urban challenges in Tehran with its several ramifications highly intertwined with people’s daily lives. It is repeatedly argued by scholars and professionals [72,83,84,85] that the current trend of increasing urban density is destructive to the city’s future and urban life.

The case study methodology is chosen as the most appropriate approach given the interpretive paradigm adopted in this research, its contextual focus, and the nature of the research questions. A single case-study approach with multiple embedded units of analysis is used where the case is the problematic process of urban densification in Tehran and the units of analysis are three residential neighbourhoods that are representative of the specific neighbourhood type which is the primary setting of urban densification in the city.

The rationale behind investigating multiple units of analysis is based on theoretical replication design. Theoretical replication [86] is a suitable means of testing theoretical frameworks. In this process, the researcher studies units that are expected to produce contradictory results and rival explanations. The present study seeks not to compare the units but, instead, to explore their conflicting results to gain in-depth and detailed insights into the facets of the relationship between perceived density and place attachment. The accumulation of in-depth data from three different neighbourhoods will add up to the knowledge in the understudied field of human-environment relations in the context of Tehran.

With an emphasis on the perceptual aspects of place experience and the subjective dimensions of social sustainability, this study maintains its focus on two perceptual concepts: experience of density and densification and place attachment. To study these concepts, a careful inquiry into the human experience of social reality and his/her understanding of the surrounding environment qualities is essential. Data collection is therefore carried out through a mixed method approach, which could be best explained as mixed epistemology or ‘pragmatic philosophical standpoint’ [87]. In research design, pragmatic approach is concerned with the extent to which research procedure serves research purposes rather than confining itself to choose a side in the duality of social constructivism/positivism. This research also takes a humanistic approach in terms of the focus of inquiry and its theoretical stance.

The insights presented in this paper are extracted from sixteen in-depth interviews conducted as part of a larger study on the experience of density and place attachment in two neighbourhoods in Tehran. The two neighbourhoods, Gisha and Afsariyeh, were chosen through a systemic selection process to ensure similar urban form and age but different population densities. Both neighbourhoods are characterised by their distinctive gridiron street pattern, apartment blocks and residential use.

The neighbourhood selection process encompassed two main stages. At the first stage, the age criterion was used to identify the residential neighbourhoods developed during the 1960s and 1970s in Tehran, a time when the city witnessed a rapid modernisation process and substantial urban growth through new residential developments. Having the same age reassures that all the identified neighbourhoods have gone through identical densification process and also the communities within them have had similar chances to shape and evolve in the course of time. Ten neighbourhoods were identified at the end of the first stage.

At the second stage, four selection criteria were applied to the identified neighbourhoods as urban layout, land-use, housing\building type, and population density. These criteria are derived from the urban form model proposed by Dempsey et al. [88]. The aim of this step was to select neighbourhoods with similar urban layout, land-use pattern and housing type, and different population density levels. The fixed preferences for the three urban form elements were gridiron pattern for the layout, residential use for the land-use and row-apartment for the housing typology. Adhering to these criteria ensured that the selected neighbourhoods represent the physical features of the particular typology that is the main setting of urban densification process in Tehran. Among the ten identified neighbourhoods, four areas represented gridiron urban layout, residential use and row apartment typology. Lastly, a formal population density classification [89] was used which categorise Tehran’s neighbourhoods into five classifications, from very low to very high gross population density: very low (1–70 pph); low (70–130 pph); medium (130–200 pph); high (200–300 pph); and very high (300–400 pph). All the four neighbourhoods fell into the ‘high’ and ‘very high’ categories. Among those, Gisha (high population density) and Afsariyeh (very high population density) were selected because of their different geographic location in the centre and periphery of Tehran (see Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 1.

The location of the two neighbourhoods in Tehran.

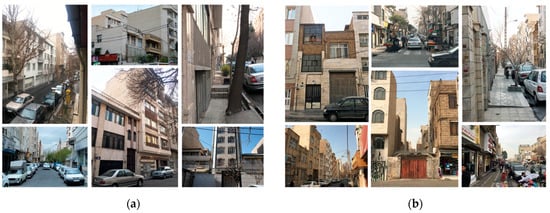

Figure 2.

Satellite image of the case study neighbourhoods (a) Gisha; (b) Afsariyeh. Source: Google Maps.

Figure 3.

Images from the case study neighbourhoods (a) Gisha; (b) Afsariyeh. Source: author.

The interviews were conducted between March and May 2019. The interviewees were local residents of the two neighbourhoods and were selected among the participants of the previous stages of the research based on the nested sampling logic [90]. The interviewees include eight women and eight men, aged between 25 and 65.

The interviews lasted between 1 and 2 h each and provided in-depth, situated knowledge of the local residents’ understanding and interaction with place. Each interview was founded upon learnt knowledge from the previous ones and sought both literal and theoretical replication [91]; thus, each interview was altered in its structure to make sure it includes refined questions about different aspects of the topic. Each interview was digitally recorded and transcribed by the researcher. The interviews were conducted in Farsi. To avoid translation pitfalls and linguistic bias, and also for the sake of time and resource constraints, the transcripts were not translated into English and the analysis was carried out in the original language. Nevertheless, the researcher selectively translated excerpts of the interviews to support the arguments and present the identified themes and patterns in the data. All the translations were done by the main researcher and no professional translation service was used.

The semi-structured interview protocol was designed with the aid of previous studies’ findings and survey results on the attributes of perceived density, experiences of densification and the construct of place attachment in Tehran. The interview questions were organised around topics that were expected to be of significant importance and relatable for the locals. Instead of having a rigid and orderly structure of questions to ask, the protocol was organised around eight overarching themes to be covered. These themes included:

- Safety measures, perception of safety, safety at night

- Social ties, family relations, friend networks

- Sense of pride

- Demographic turnover and immigration

- Knowing neighbours and having strong neighbourly relations

- Maintaining privacy

- Crowding

- Transformation of the neighbourhood

The order of covering these themes was not pre-determined and was contingent upon the flow of the conversation where topical trajectories are inevitable and unexpected but relevant topics might emerge. Small has proposed a unique approach to formulate in-depth interview studies [91] by arguing that case study logic—as opposed to sampling logic—is better suited for semi-structured interviews. Within this approach, each individual could be thought of as a single experiment. This study followed Small’s recommendation for conducting interviews. This strategy, while maintaining a degree of authority for the researcher to control the topic and stick to the protocol, opened the room for spontaneity and allowed deep impressions and insights to develop and emerge to the surface.

The interview data were analysed using qualitative thematic analysis method [92] and by the use of MAXQDA software. The whole data set was then coded based on the pre-defined codes into the MAXQDA software program by employing an abductive approach [93]. In addition to the interview data, the rest of collected primary data—memos and notes, informal chats insights—alongside secondary data from the community newsletters, local newspaper articles and social media content were incorporated into the database.

4. Results

The results of the thematic analysis of the interview data provided contextualised empirical findings that could elucidate on the construct of place and place attachment and further explain the complex relationship between densification and social sustainability. The four identified themes are concerned with and reflect upon and ontological duality in place meaning, a temporal dimension in experiencing density and formation of attachment, the residents’ reactions and responses to change, and the external intervening factors. Each of these thematic categories has implications for and linkages to density and social sustainability discourse as explained below.

The analysis provided some insights about the construct of place and the meanings that Tehranis assign to their place of residence. The findings highlighted an explicit parallelism in the meaning of place for Tehranis—which can be perhaps generalised to the Iranians in general—and showed a dissociation between the residents and their neighbourhood as a place. The meaning of place in Tehran could be divided into two parallel metaphorical ideas: (1) an internal, socially constructed and more tangible idea of place at the micro-scale mainly corresponding to an individual’s life events, everyday life, routine activities and lived experience; and (2) an external, structurally-formed idea of place connected to the changes occurring at the macro scale within which organisational forces, institutional regulations and governmental formalities seem to have more authority and control. The latter idea must be still considered as a ‘place’ despite its seemingly disconnection from daily experiences and individualised meanings. The parallel lives of these places concomitantly carry on, although at different institutional levels and with the involvement of distinctive actors. It is mainly due to this parallelism that the locals conceive the structural elements of place and their transformations as unchallengeable and as already ratified.

Furthermore, the residents were conceiving of urban densification in relation to the latter idea of place; as a trajectory of change to which they have no authority to control, no way to influence and no right to challenge. In this sense, changes in place occur systematically and therefore, are beyond the sphere of influence of the local community. This has a huge implication for the relationship between urban densification and social sustainability by refuting the highly debated idea that high urban density could contribute to social sustainability by improving sense of community and cohesion [94,95,96]. Instead of exploring the link between social sustainability and urban density, it seems more relevant to explore the process of densification as a place change trajectory and its impact on social sustainability.

As a result of this ontological duality of place, the locals tend to interpret their neighbourhood as an untouchable, inaccessible urban superstructure that is being transformed based on an incomprehensible upper-level knowledge of technicity and unknown logic of governmentality which is seemingly unchallengeable. A significant consequence of the duality of place is a unique type of social indifference or apathy, resulting from a situation where qualitative values of the city have reduced to quantitative measures. This social indifference resembles what Simmel termed as “blasé” in the ‘Metropolis and Mental Life’ [97]—superficiality, greyness, and alienation. Indifference has also repercussions for the relationship between perception of densification and place attachment: no matter how and to what extent a place’s social and spatial organisation changes; as long as the locals conceive these changes as happening at an institutional level beyond their level of influence, they will not proactively react to mitigate the adversities. The implication of this parallelism for social sustainability would emerge in the form of a disjuncture between the individual and both social and physical domains of place, manifested through reduced social participation and engagement, lack of sense of community, and increased social apathy.

The findings identified an unexpected temporal phenomenon related to the memory of place and the process of its diminishment through place change. Loss of place memory could affect an individual’s cognition of place and distort the representations of the past within the place [64,66,98]. One resident explained his emotional reaction to a massive change in Gisha by which a local gathering point of the residents located on a natural leafy hill was destroyed, and the trees were cut down to make space for an inner-city highway: “I was burst into tears … That hill was very important to us … I called everywhere I could and asked them to stop it, I felt really hopeless” (Male, 60s, Gisha). The same person, when was asked whether he would stay in the same neighbourhood if the leafy hill was still there said: “I think so. Now I do not feel attached to Gisha at all, but if the hill was still there, perhaps I could still feel some bonds with the neighbourhood” (Male, 60s, Gisha). The temporal dimension is present in social sustainability discussions where the conditions of present and future are distinguished and compared [99]. Social sustainability as an ongoing process towards achieving desirable social outcomes could be framed through a temporal lens. It could be argued that the multiple challenges faced by a society—environmental, social, economic and spatial—are the result of past behaviours and conditions and similarly, the present status will have future consequences. Therefore, the past trajectories, present conditions and future pathways of a place, as experienced by its users become strong elements and determinants of its transition towards sustainability.

Place memory is a psychological construct formed at both personal and collective levels and through the process of being in place. It contains a spectrum of personalised sentiments and reminiscences developed at the moments of solitude and being among others. Place memory takes shape as a result of these moments. Destroying the material traces of sites “resets the clock on the embodied relationship between the individual and the environment.” [100] (p. 2326). The metaphoric expression of ‘resetting the clock’ of place and the individual’s relationship with it perfectly explains the situation where destruction of the material elements of place leads to its erosion and to the birth of a new place out of the ashes of the old.

The findings also revealed the various ways through which residents react and respond to urban densification. Findings showed that respondents in Tehran had a strong tendency towards taking one of the three choices of acceptance, adaptation, and personal relocation. The socio-spatial transformation of the neighbourhood resulted by soft densification could be aligned with some residents’ life expectations and desires. It is thus not surprising that a proportion of residents would positively evaluate the place changes and as a result, their relationship with the place will boost. In the case of Tehran, residents showed satisfaction with the revitalised urban landscape, improved housing quality or even from an economic perspective, with the added property value which are all spinoffs of urban densification. The latter issue regarding increased property value underscores the imperative role of economic infrastructure and the inherent politics of place change in people-place relations. It also highlights the distinctive roles that individuals play in the economic field of the housing market as homeowners and renters, and their trade-offs.

At the other end of the spectrum, reaction to place change for the residents to whom the trajectory of densification and place change is adverse and troublesome often takes the form of adaptation. Adaptation refers to a condition in which individuals accept their fate and adjust their lifestyle, expectations, needs, and routines in order to reach a compromise with the new socio-spatial order of place. The prevalence of place adaptation in the residents’ narratives—either first-hand or second-hand—highlights the status of passiveness among the residents towards place change. The changes in place are presumably negatively interpreted by the individual; however, due to a potentially high level of attachment—which seems to remain untouched by the changes—or due to various external factors such as housing market determinism, the individual opts for adaptation instead of relocation or any other potential response. An example of place adaptation was found in one resident’s account of doing daily supermarket shopping. The relevant participant maintained that: “… due to traffic congestion and crowdedness of the high street, I do not do the shopping myself … Instead, I order whatever I need from supermarket, grocery store or bakery on the phone and they deliver to my home. They all know me so I can pay later. It’s very convenient.” (Male, 60s, Gisha).

In this case, the respondent has changed his lifestyle and is willing to pay the extra delivery fee for routine shopping. Others who are not willing to pay extra delivery fee must come up with alternative strategies to do their regular shopping: “… there is a big vegetable market in the neighbourhood with affordable prices. I used to go there by my car … I had no choice because sometimes I buy kilos of fruits, vegetables and other products15 … But now, there is no parking space around the market anymore. Usually, I have to park two or three blocks away, go shopping and come back … it’s very hard for me. Recently I go with my son, he stays in the car [double-parking] and picks me up in front of the market … what else can I do!” (Female, 60s, Gisha).

The strategy adopted by this household contributes, in turn, to higher traffic congestion and creation of a cluttered landscape in front of the market. Nevertheless, this household has opted for making changes in its lifestyle despite the troublesome nature of this change. Residents also employ different strategies to bypass traffic congestion in their neighbourhood, particularly during rush hours. One participant in Gisha said: “the main boulevard is always packed with cars … I never take that road. I use rat runs to avoid traffic. Non-local motorists are not aware of these routes.” (Male, 30s, Gisha).

One young interviewee stated that he actively tries to adapt himself to the changes caused by densification such as exacerbated traffic congestion, crowding and lack of privacy: “We [household] adapt ourselves because we feel part of Gisha. I got a motorbike to avoid traffic for instance … Now I don’t waste my time in the evening traffic anymore.” (Male, 20s, Gisha)

The last refuge for a discontent individual is to relocate. Interview analysis revealed several narratives of relocation triggered by or rooted in the process of urban densification. Most commonly, and particularly during the 1990s, a new mode of reconstruction became prevalent through which homeowners were persuaded by private developers to get engaged in residential speculation and shared redevelopment of their properties. An exciting account of persuading owner-residents to get involved in the rebuilding process utilised scaremongering techniques targeting safety issues of the old structures. The concerns over the structural safety of the old buildings particularly escalated in the aftermath of a series of earthquakes in the region during the 2000s. One resident recalled that, in those days: “everyone was talking about structural deficiencies of the old house structures. Out of safety fears, rebuilding became a very popular trend in the area.” (Male, 50s, Gisha). Residential rebuilding processes also triggered a domino effect of further constructions. One resident who used to live in a single-family house and, interestingly, had a very positive view of the old urban landscape said: “I’d say we were forced to sell out our home and move out just because our adjacent plot started construction and it impacted our home’s structural rigidity … there were cracks on the wall, even the floor was sloped down and we could see it with the naked eye.” (Female, 60s, Gisha)

These accounts highlight the initiating point of an institutionalised developmental trend across the neighbourhoods of Tehran which during the coming decades became one of the fundamental causes of the socio-spatial transformation of the place and the main driver of household relocation. For the tenants, however, relocation in this sense is mostly obligatory. All these events contributed to a massive wave of moving out and social turnover. The above discussions on place adaptation and personal relocation suggest that through the process of urban densification and residential rebuilding, a particular type of place disruption occurs. Place disruption in this case seems to strip place of its significant meaning and thus, reduces place to a mere setting of daily life, devoid of any meaningful connotation, a process which undermines social sustainability through widening the gap between the individuals and their place of residence. Prevalence of economic reasoning in place change processes in Tehran re-define place as a commodity to be exchanged and create profit.

The results also suggest that the relationship between the perception of density and densification, and place attachment is mediated by at least three factors. The interviews showed that housing market dynamics and household’s economic potential and capabilities could impact people’s relationship with their place of residence. As one resident remarked: “I do not feel attached to this neighbourhood; but I cannot afford buying a property in neighbourhoods that I like, so I have to be content. What else can I do? If I were in a better financial situation, I would have certainly moved out.” (Male, 60s, Gisha).

This view echoed by another respondent who raised the issue of household priorities: “I do not like It here. But does it really matter? Considering our financial situation and property prices, we are not able to rent a better place. We have to stick to whatever we have.” (Female, 30s, Afsariyeh).

Individuals have aspirations and desires about their place of residence. The ability to satisfy these desires is arguably contingent upon the macro-scale structural mechanisms. Under the circumstances which resemble a degree of economic determinism, individual prioritisation becomes a means of survival.

Another intermediary factor was concerned with the socio-cultural profile of the residents. An important, rather unexpected insight was regarding a perceived positive impact of densification. Some residents reported that densification—or in their own term, ‘neighbourhood developments’—resembles a form of urban transformation which brings about renewal and modernisation. In Tehran, the discussed urban change and residential rebuilding primarily take place by replacing the old, outmoded dwelling types—e.g., detached, terraced houses, two- to three-storey walk-up buildings- with “modern” apartment blocks. The new apartment blocks not only offer a desirable, contemporary and revitalised urban landscape, but also in their material attributes, provide better amenities, facilities and services such as elevator, parking spaces and centralised heating system. Therefore, it is not surprising that such changes are welcomed by a considerable group of residents. During the preliminary conducted informal chats, a participant remarked: “Density is not a problem for me. I like [the neighbourhood] this way. It’s very fun … [residential rebuilding] makes the area dynamic and lively. Density is not that high.” (Male, 20s, Gisha)

The account suggests that urban densification is perceived, at least by a group of middle-class Tehranis, as a positive urban transformation process delivering their life aspirations. Nevertheless, as the preceding discussions prove, the dynamics are much more complicated than they seem. There seems to be a discrepancy between what people desire, what they need, what they aspire and what they eventually get.

The last external factor mediating the relationship between the perception of densification and place attachment is concerned with the individual level, psychological needs, and personal preferences [98,101,102]. One resident in Gisha believed that although the neighbourhood is generally crowded, busy and in her opinion, lively, there are some sub-areas in the neighbourhood which are quieter and suitable for those who seek tranquility and peace. Another participant who was living alone maintained: “I prefer to live in a busy area. I don’t mind if there is traffic because I don’t drive. But if I live in a quiet area, I will get depressed” (Female, 60s, Gisha). These accounts highlight the unique psychological conditions of individuals and their preferred criteria for their living environment. These factors, to a great degree, determine the type of reaction that one shows to urban densification and place change and ultimately, define the extent to which densification threatens or enhances their place attachment.

Overall, the findings of this section suggest that the economic setting, housing market attributes, urban political landscape, cultural aspirations, social imaginaries and individual-psychological conditions are micro to macro scale determinants of the way urban densification is being unfolded, experienced and perceived at the local level and subsequently, how this process of change could impact social sustainability of urban neighbourhoods. The intervening factors support the context-specific, place-based theorisation of social sustainability and refute any universal presupposition about the nature of the relationship between social sustainability and urban density.

5. Discussion

This paper looked at the theoretical intersection of a place-based approach to social sustainability and soft densification. It attempted to elaborate on the lived experiences of urban densification and their interconnection with people-place relations in Tehran. The core theoretical argument of the paper was that urban social sustainability could be achieved through consolidation of place. This act of place consolidation should not be mistaken with the reactionary modes of parochialism, NIMBYism or exclusionary politics. Conversely, it is a call for more proactive re-definition of place as a spatio-temporal flow, [103] and then utilising it as a setting for social mobilisation and rationalisation in the realm of everyday life. This progressive place-based theorisation of urban social sustainability goes against the assumption that local attachment is essentially exclusionary.

The incremental, piecemeal nature of soft densification denotes temporality inherent in urban planning processes. Slow planning [104] is associated with strong economic incentives for the developers and politics of placemaking. On another level, incremental development across a vast urban landscape renders the city at the status of waiting and becoming. The striking juxtapositions constructed out of the soft densification process accentuate the difference between the old and the new, stability and progress, finished and unfinished, and lawful and unlawful.

The behavioural patterns and the residents’ reaction to place transformation as discussed in this paper reveal some key findings. Regardless of the promoting or undermining effect of place transformation, the multiple reflexive trajectories of the residents proved to be highly influenced by externalities such as the household’s economic status. This has huge implications for the studies of urban social sustainability and place attachment as it indicates challenges of drawing generalisation and transplanting best practice models across different geographic and institutional contexts. A blanket approach to generalise over the impacts of densification in urban social sustainability is harmful and negligent of the specific social, cultural, and political attributes of urban localities.

The identified modes of response—acceptance, adaptation, and relocation—are critical features of people-place relations and explain how these relations are modified responding to urban densification. The evidence from Tehran suggests that loss of place attachment due to urban densification does not necessarily lead to active modes of response to save the place such as local resistance movements; instead, residents’ response patterns show a strong tendency towards ‘transformative adaptation’ [105] through changing their lifestyle and daily routines, and voluntary relocating to adapt to the new socio-spatial order. Different modes of response also highlight the complex politics of place transformation in cities, highlighting the power relations, and the trade-offs between various stakeholders. The passive nature of the identified response patterns, combined with the identified parallelism in place meaning and implications for the residents signifies a state of social apathy or alienation; a condition resulted by place erosion, unchallengeable developmental attitude of the capital and property finance, and lack of effective, legally-supported and binding participatory platforms at the local level.

The process of place transformation through soft densification in Tehran is a political economic narrative of change. Under the conditions of economic distress and housing market instability and while the residents’ basic needs are at stake, their relationship with the neighbourhood is unlikely to go beyond pure satisfaction of essential needs. Under these circumstances, it is also doubtful for the residents to be concerned about densification, crowding, and neighbourhood change.

The efforts to frame and theorise urban social sustainability based on place are concerned with and mediated by the scalar politics of place and people. The dichotomy between the place-based discourse and the developmental framing of sustainability highlights the underlying questions of what kind of place we aim to create and what society do we want to sustain [53]. Asking these questions is the prerequisite of any attempt of re-defining the social dimension of sustainability and approaching the politics embedded within it.

Urban social sustainability is an emplaced concept, contingent on the particular social conditions of place. The meaning of place and the nature of the people-place relationship are strong determinants of social sustainability of an urban community. Caring for place and active engagement in its formation and alteration processes, or a complete apathy towards place transformation are the two ends of the spectrum and illustrate different scenarios and dynamics of a place-based model of social sustainability. This is particularly relevant if we define social sustainability of residential neighbourhoods in relation to their spatial organisation and by adopting the socio-spatial dialectic lens [36].

An emplaced theorisation of urban social sustainability will have notable multi-scalar policy implications for urban governance and development plans. Primarily and by shifting the attention towards the level of everyday life, this approach emancipates social sustainability discourse from theoretical ambiguities, loose terminology and nullified application. The shift is also in line with what Colantonio suggested as a hard to soft transition in social sustainability indicators [44] which necessitates creation of novel policymaking mechanisms and democratic structures of citizen engagement in urban governance and decision-making at the local level. In practice, this means that developers, policymakers, urban practitioners and managers should reconsider the common language of social sustainability which in some instances is devoid of the radical potentials of urban sustainability and change.

Future investigations need to explore the historical, social and political processes through which places are made and remade, and to outline the political capacities of making place attachment as a pathway towards creating socially sustainable communities. Further research could be pursued by posing questions concerned with the pragmatic considerations of devising densification policies and their implementation. The divergent pragmatic approaches to densification would create different scenarios and will lead to different futures. This focus in particularly timely and critical in the context of the global South where the cities are struggling with financial resources, population boom, and robust planning and governance structure. Future research could also explore the political economy of urban densification, the actors and stakeholders involved in the process and their political interferences. Such lens could highlight the commonly neglected fight for profit over rebuilding and densification and the power relations involved in the transformation of the cities. These considerations exclusively matter as they clarify the concealed drivers behind urban intensification projects and bring forward the class struggle dynamics that shape urban form.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University College London (9587/001 approved on 18 December 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns of the participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Shirazi, M.R.; Keivani, R. Critical reflections on the theory and practice of social sustainability in the built environment—A meta-analysis. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 1526–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamiduddin, I. Neighbourhood Planning Strategies in Feiburg, Germany. Soc. Sustain. Resid. Des. Demogr. Balanc. 2015, 86, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sendra, P.; Fitzpatrick, D. Community-Led Regeneration: A Toolkit for Residents and Planners; UCL Press: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 178735606X. [Google Scholar]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social Sustainability: A New Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Howes, Y. Disruption to place attachment and the protection of restorative environments: A wind energy case study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjærås, K. Towards a relational conception of the compact city. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 1176–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamiduddin, I.; Adelfio, M. Social sustainability and new neighbourhoods: Case studies from Spain and Germany. In Urban Social Sustainability: Theory, Policy and Practicepolicy; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi, M.R.; Keivani, R. Social sustainability of compact neighbourhoods evidence from London and Berlin. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyttä, M.; Broberg, A.; Haybatollahi, M.; Schmidt-Thomé, K. Urban happiness: Context-sensitive study of the social sustainability of urban settings. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2016, 43, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P. Rethinking NIMBYism: The role of place attachment and place identity in explaining place-protective action. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 19, 426–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Thomé, K.; Haybatollahi, M.; Kyttä, M.; Korpi, J. The prospects for urban densification: A place-based study. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 025020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, F.M. Place-Temporality and Urban Place-Rhythms in Urban Analysis and Design: An Aesthetic Akin to Music. J. Urban Des. 2013, 18, 383–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fincher, R.; Pardy, M.; Shaw, K. Place-making or place-masking? The everyday political economy of “making place”. Plan. Theory Pract. 2016, 17, 516–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpas, J. Place and Experience: A Philosophical Topography; Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Seamon, D. Place, Place Identity, and Phenomenology: A Triadic Interpretation Based on J.G. Bennett’s Systematics. In The Role of Place Identity in the Perception, Understanding, and Design of Built Environments; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2012; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, T. Place: A Short Introduction; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; ISBN 9780470655627. [Google Scholar]

- Madden, D.J. Neighborhood as spatial project: Making the urban order on the downtown Brooklyn waterfront. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 471–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S.; Madanipour, A. Localism and the ‘Post-social’ Governmentality. In Reconsidering Localism; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shirazi, M.R. Compact Urban Form: Neighbouring and Social Activity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Relph, E. Geographical experiences and being-in-the-world: The phenomenological origins of geography. In Dwelling, Place and Environment; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1985; pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. A global sense of place. Marx. Today 1991, 308, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibby, P.; Henneberry, J.; Halleux, J.M. Under the radar? ‘Soft’ residential densification in England, 2001–2011. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2020, 47, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karampour, K. Implications of density bonus tool for urban planning: Relaxing floor area ratio (FAR) regulations in Tehran. Int. Plan. Stud. 2021, 26, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadami, M.; Dittmann, A.; Safarrad, T. Lack of Spatial Approach in Urban Density Policies: The Case of the Master Plan of Tehran. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. The 21st-century metropolis: New geographies of theory. Reg. Stud. 2009, 43, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macarthur, D. Place and Experience: A Philosophical Topography. Philos. Rev. 2001, 110, 632–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, E.S. Between Geography and Philosophy: What Does It Mean to Be in the Place-World? Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2001, 91, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, E.S.; Hartman, L.; Hagemann, F. From place to emplacement: The scalar politics of sustainability. Local Environ. 2020, 25, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. The experienced psychological benefits of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1978; Volume 7, ISBN 0816638772. [Google Scholar]

- Relph, E. (Ed.) Place and Placelessness; SAGE Publishing Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.R. Making sense of “place”: Reflections on pluralism and positionality in place research. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 131, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, A. Understanding Place BT—Place, Space and Hermeneutics; Janz, B.B., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 9–22. ISBN 978-3-319-52214-2. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaney, J. Parochialism—A defence. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 37, 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soja, E.W. The Socio-Spatial Dialectic. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1980, 70, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, E. The Fate of Place: A Philosophical History; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, A. Culture sits in places: Reflections on globalism and subaltern strategies of localization. Political Geogr. 2001, 20, 139–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. What Time is This Place? Mit Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1972; ISBN 0262620324. [Google Scholar]

- Seamon, D. Place attachment and phenomenology: The synergistic dynamism of place. In Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, K.; Wilson, L. A critical assessment of urban social sustainability. In Proceedings of the 4th State of Australian Cities National Conference, Perth, Australia, 24–27 November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi, M.R.; Keivani, R. Social sustainability discourse: A critical revisit. In Urban Social Sustainability: Theory, Policy and Practice Policy; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Littig, B.; Griessler, E. Social sustainability: A catchword between political pragmatism and social theory. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 8, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colantonio, A. Traditional and Emerging Prospects in Social Sustainability. In Measuring Social Sustainability: Best Practice from Urban Renewal in the EU; Oxford Institute for Sustainable Development (OISD) EIBURS Working Paper Series; Oxford Brookes University: Headington, UK, 2008; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Arundel, R.; Ronald, R. The role of urban form in sustainability of community: The case of Amsterdam. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2017, 44, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larimian, T.; Freeman, C.; Palaiologou, F.; Sadeghi, N. Urban social sustainability at the neighbourhood scale: Measurement and the impact of physical and personal factors. Local Environ. 2020, 25, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujang, N.; Kozlowski, M.; Maulan, S. Linking place attachment and social interaction: Towards meaningful public places. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2018, 11, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.R.; Keivani, R. The triad of social sustainability: Defining and measuring social sustainability of urban neighbourhoods. Urban Res. Pract. 2019, 12, 448–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seghezzo, L. The five dimensions of sustainability. Environ. Politics 2009, 18, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manzi, T.; Lucas, K.; Jones, T.L.; Allen, J. Understanding social sustainability: Key concepts and developments in theory and practice. In Social Sustainability in Urban Areas: Communities, Connectivity and the Urban Fabric; Manzi, T., Lucas, K., Jones, T.L., Allen, J., Eds.; Earthscan Publications: London, UK, 2010; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcraft, S. Understanding and measuring social sustainability. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2015, 2, 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Luke, T.W. Neither sustainable nor development: Reconsidering sustainability in development. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 13, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M. Social sustainability: Politics and democracy in a time of crisis. In Urban Social Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 27–41. ISBN 1315115743. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, M. Social sustainability and the city. Geogr. Compass 2010, 4, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M.; Iveson, K. Recovering the politics of the city: From the ‘post-political city’ to a ‘method of equality’ for critical urban geography. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2015, 39, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S.; Madanipour, A. Reconsidering Localism; Davoudi, S., Madanipour, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 9781315818863. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Q. Neighbourhoods, communities and the local scale. In Localism and Neighbourhood Planning: Power to People; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2017; pp. 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N. Implosions/explosions. In Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization; JOVIS: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stedman, R.C. Sense of place as an indicator of community sustainability. For. Chron. 1999, 75, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Omann, I.; Spangenberg, J.H. Assessing Social Sustainability: The Social Dimension of Sustainability in a Socio-Economic Scenario. In Proceedings of the 7th Biennial Conference of the International Society for Ecological Economics, Sousse, Tunisia, 6–9 March 2002; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, A. Social Sustainability: An Exploratory Analysis of Its Definition, Assessment Methods Metrics and Tools; EIBURS Working Paper Series; Oxford Brookes University: Headington, UK, 2007; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bramley, G.; Dempsey, N.; Power, S.; Brown, C.; Watkins, D. Social sustainability and urban form: Evidence from five British cities. Environ. Plan. A 2009, 41, 2125–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.Y. Space and Place: Humanistic Perspective; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1979; pp. 387–427. [Google Scholar]

- Manzo, L.; Devine-Wright, P. Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.; Hernandez, B. Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Dynamics: New York, NY, USA, 2018; 41p.

- Madanipour, A. Tehran: The Making of a Metropolis; Academy Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; ISBN 0471957798. [Google Scholar]

- Bayat, A. Tehran: Paradox City. New Left Rev. 2010, 66, 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Mashayekhi, A. The Politics of Building in Post-Revolution Tehran. In Routledge Handbook on Middle East Cities; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 196–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayesteh, H.; Steadman, P. The impacts of regulations and legislation on residential built forms in Tehran. J. Sp. Syntax 2013, 4, 92–107. [Google Scholar]

- Shayesteh, H.; Steadman, P. Coevolution of urban form and built form: A new typomorphological model for Tehran. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2015, 42, 1124–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, R.; Hickman, H.; While, A. Planning control and the politics of soft densification. Town Plan. Rev. 2020, 91, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touati-Morel, A. Hard and Soft Densification Policies in the Paris City-Region. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2015, 39, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, V. Planning and the ‘stubborn realities’ of global south-east cities: Some emerging ideas. Plan. Theory 2013, 12, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyttä, M.; Broberg, A.; Tzoulas, T.; Snabb, K. Towards contextually sensitive urban densification: Location-based softGIS knowledge revealing perceived residential environmental quality. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 113, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibby, P.; Henneberry, J.; Halleux, J.M. Incremental residential densification and urban spatial justice: The case of England between 2001 and 2011. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 2117–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampour, K. Municipal Funding Mechanism and Development Process: A Case Study of Tehran. Ph.D. Thesis, University College London, London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Madanipour, A. Sustainable Development, Urban Form, and Megacity Governance and Planning in Tehran. In Megacities; Sorensen, A., Okata, J., Eds.; Library for Sustainable Urban Regeneration Book Series; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2011; Volume 10, pp. 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertaud, A. Tehran Spatial Structure: Constraints and Opportunities for Future Development; Ministry of Housing and Urban Development: Tehran, Iran, 2003.

- Ghadami, M.; Newman, P. Spatial consequences of urban densification policy: Floor-to-area ratio policy in Tehran, Iran. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2019, 46, 626–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomehpoor, M.; Najafi, G.; Shafia, S. Extended abstract: Evaluation of relationship between density and social sustainability in Tehran Municipality’s regions. Geogr. Environ. Plan. 2013, 23, 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Zareyian, M. The Social Impacts of Increasing Urban Density in Tehran; Housing & Urban Development Research Center: Tehran, Iran, 2015. (In Persian)

- Shieh, E.; Shojaei, R. The Impacts of Increasing Urban Density on Neighbourhood’s Social Qualities; The Journal of Housing Economy: Tehran, Iran, 2008. (In Persian) [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 5, ISBN 9781412960991. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L. Pragmatism as a Paradigm for Social Research. Qual. Inq. 2014, 20, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Brown, C.; Raman, S.; Porta, S.; Jenks, M.; Jones, C.; Bramley, G. Elements of Urban Form; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 21–51. [Google Scholar]

- Habibi, S.-M.; Hourcade, B. Atlas of Tehran Metropolis; Tehran Urban Processing Planning Co.: Tehran, Iran, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Collins, K.M.T. The Qualitative Report A Typology of Mixed Methods Sampling Designs in Social Science Research. Qual. Rep. 2007, 12, 281–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, M.L. How many cases do I need? Ethnography 2009, 10, 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic Analysis. In Analysing Qualitative Data in Psychology; SAGE Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; Tavory, I. Theory construction in qualitative research: From grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociol. Theory 2012, 30, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, M. The compact city fallacy. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2005, 25, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabareen, Y.R. Sustainable Urban Forms: Their Typologies, Models, and Concepts. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2006, 26, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.; Jenks, M.; Williams, K. The Compact City: A Sustainable Urban Form? Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, G. The metropolis and mental life. In The Urban Sociology Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment, place identity, and place memory: Restoring the forgotten city past. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.; Evans, J. Rescue Geography: Place Making, Affect and Regeneration. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 2315–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.; Graefe, A.; Manning, R.; Bacon, J. Effects of place attachment on users’ perceptions of social and environmental conditions in a natural setting. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Wirth, T.; Grêt-Regamey, A.; Moser, C.; Stauffacher, M. Exploring the influence of perceived urban change on residents’ place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 46, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A. Regions unbound: Towards a new politics of place. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2004, 86, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raco, M.; Durrant, D.; Livingstone, N. Slow cities, urban politics and the temporalities of planning: Lessons from London. Environ. Plan. C Politics Sp. 2018, 36, 1176–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.; Murphy, C.; Lorenzoni, I. Place attachment, disruption and transformative adaptation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 55, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).