Understanding the Antecedents and Consequences of Service-Sales Ambidexterity: A Motivation-Opportunity-Ability (MOA) Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

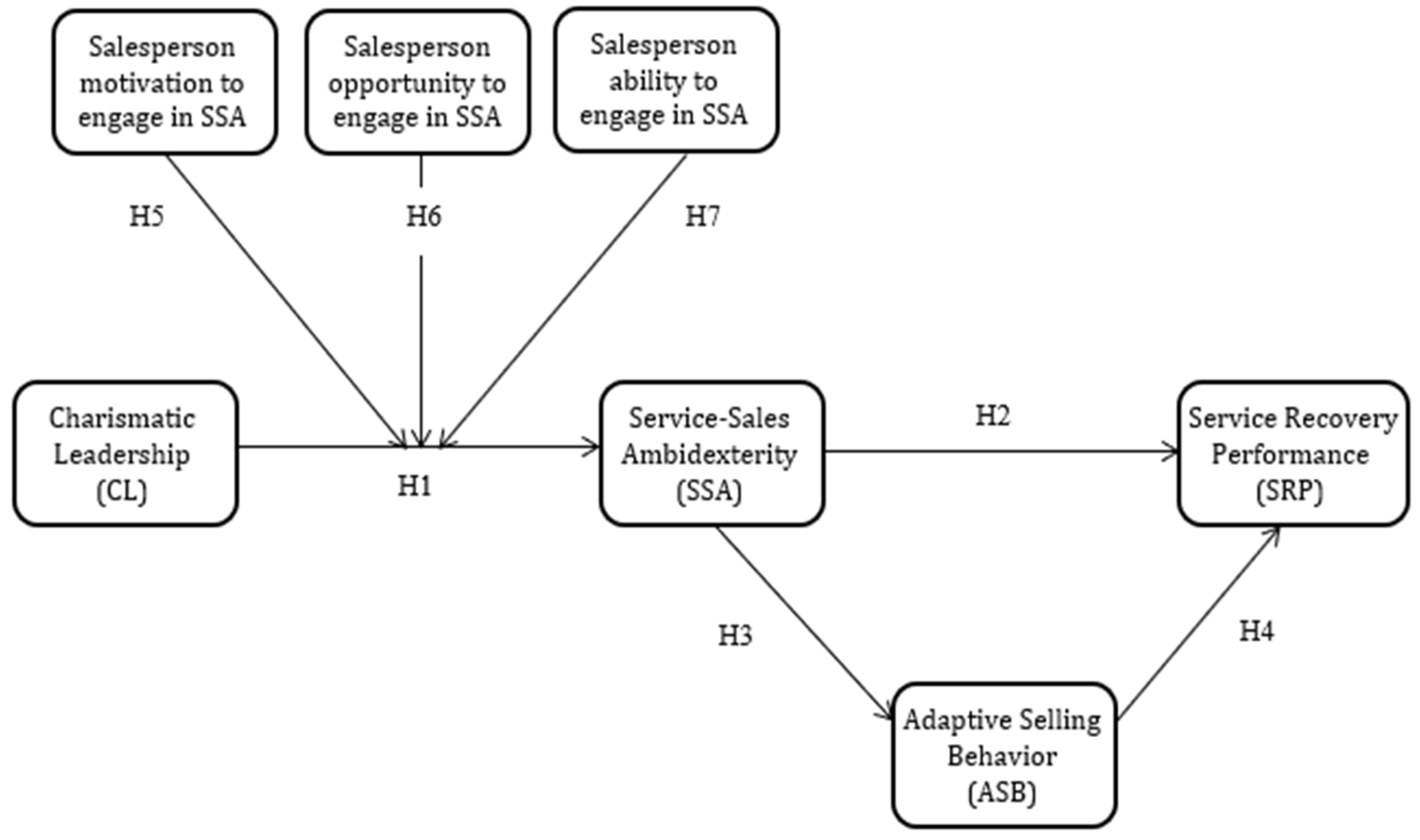

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. The Motivation, Opportunity and Ability Framework

2.2. Charismatic Leadership and Service-Sales Ambidexterity

2.3. Service-Sales Ambidexterity and Service Recovery Performance

2.4. Service-Sales Ambidexterity and Adaptive Selling Behavior

2.5. Adaptive Selling Behavior and Service Recovery Performance

2.6. The Moderating Role of Salesperson’ Motivation, Opportunity and Ability

3. Research Design

3.1. Selection of Respondents and Sample Size

3.2. Instrument and Variables

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Data analysis and Results

4.1. Assessment of Measurement Model

4.2. Common Method Variance

4.3. The Goodness of Fit (GoF)

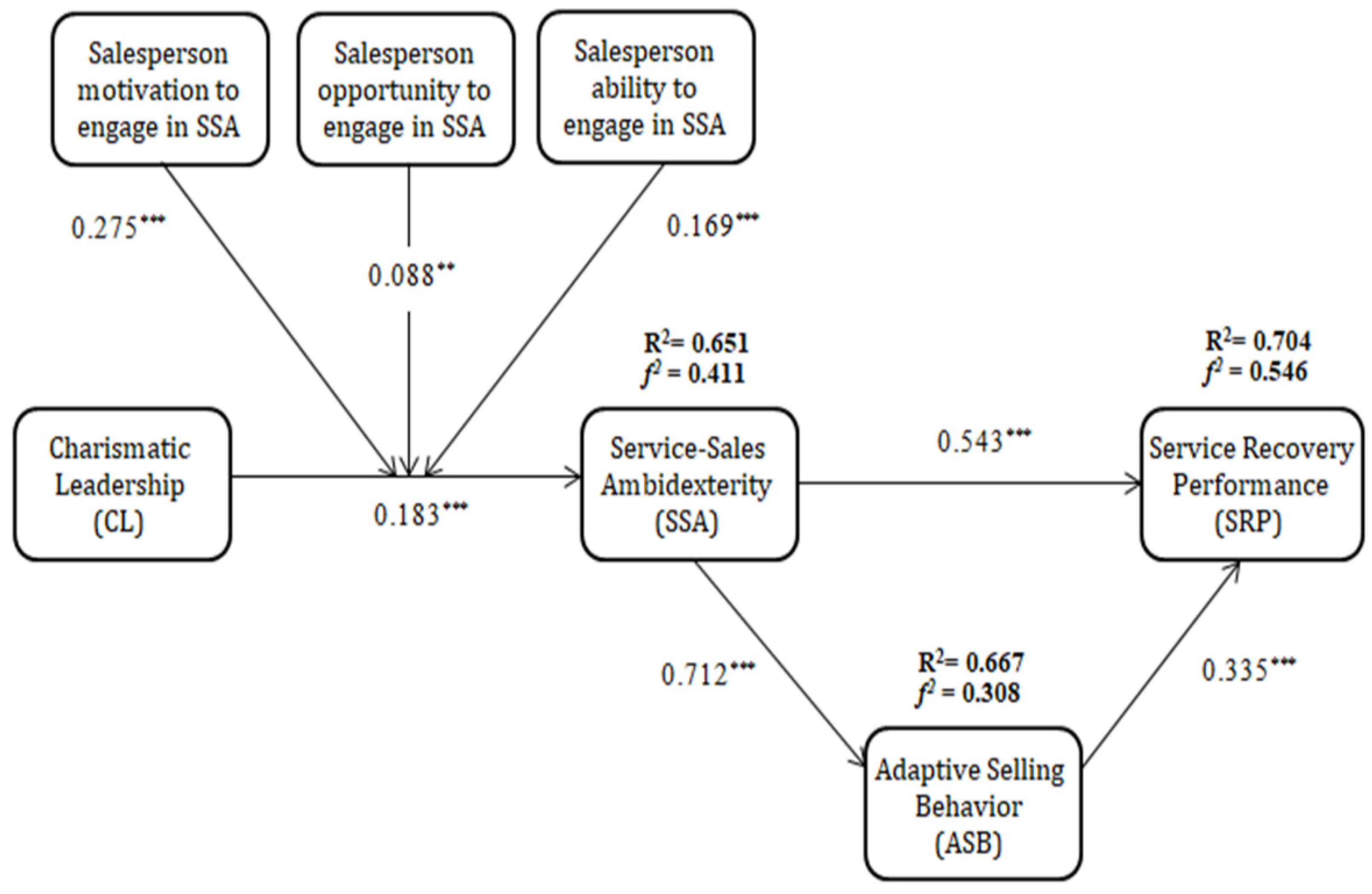

4.4. Results of Proposed Hypotheses

4.5. Moderating Effects

5. Discussion

5.1. Major Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Managerial Implications

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yi, H.-T.; Cha, Y.-B.; Amenuvor, F.E. Effects of Sales-Related Capabilities of Personal Selling Organizations on Individual Sales Capability, Sales Behaviors and Sales Performance in Cosmetics Personal Selling Channels. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, C.; Hur, C.; Ji, S. The customer orientation of salesperson for performance in Korean Market Case: A relationship between customer orientation and adaptive selling. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Junni, P.; Sarala, R.M.; Taras, V.; Tarba, S.Y. Organizational ambidexterity and performance: A meta-analysis. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, B.; House, R.J.; Arthur, M.B. The Motivational Effects of Charismatic Leadership: A Self-Concept Based Theory. Organ. Sci. 1993, 4, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T.; Thao, V.T. Charismatic leadership and public service recovery performance. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2017, 36, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faia, V.d.S.; Vieira, V.A. Generating sales while providing service: The moderating effect of the control system on ambidextrous behavior. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2017, 35, 447–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sok, K.M.; Sok, P.; De Luca, L.M. The effect of “can do” and “reason to” motivations on service-sales ambidexterity. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 55, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommovigo, V.; Setti, I.; Argentero, P. The role of service providers’ resilience in buffering the negative impact of customer incivility on service recovery performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luu, T.T. Linking authentic leadership to salespeople’s service performance: The roles of job crafting and human resource flexibility. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 84, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-B. Relevant factors that affect service recovery performance. Serv. Ind. J. 2010, 30, 891–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oflac, B.; Sullivan, U.Y.; Kaya Aslan, Z. Examining the impact of locus and justice perception on B2B service recovery. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, R.; Gabler, C.B.; Itani, O.S.; Jaramillo, F.; Krush, M.T. Salesperson ambidexterity and customer satisfaction: Examining the role of customer demandingness, adaptive selling, and role conflict. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2017, 37, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.C.; Yang, P.Y.; Chen, M.H. The determinants of academic research commercial performance: Towards an organizational ambidexterity perspective. Res. Policy 2009, 38, 936–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, J.; Gibson, C. Building Ambidexterity into an Organization. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2004, 45, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, A.; Liu, Y.; Tjosvold, D. Service leadership for adaptive selling and effective customer service teams. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2015, 46, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, G.R.; Park, J.E. Salesperson adaptive selling behavior and customer orientation: A meta-analysis. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiro, R.L.; Weitz, B.A. Adaptive Selling: Conceptualization, Measurement, and Nomological Validity. J. Mark. Res. 1990, 27, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boiral, O.; Baron, C.; Gunnlaugson, O. Environmental Leadership and Consciousness Development: A Case Study among Canadian SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 123, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClean, E.; Collins, C.J. Expanding the concept of fit in strategic human resource management: An examination of the relationship between human resource practices and charismatic leadership on organizational outcomes. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 58, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, R.; Agnihotri, R.; Hall, Z. The Ambidextrous Sales Force: Aligning Salesperson Polychronicity and Selling Contexts for Sales-Service Behaviors and Customer Value. J. Serv. Res. 2020, 23, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabler, C.B.; Ogilvie, J.L.; Rapp, A.; Bachrach, D.G. Is There a Dark Side of Ambidexterity? Implications of Dueling Sales and Service Orientations. J. Serv. Res. 2017, 20, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclnnis, D.J.; Moorman, C.; Jaworski, B.J. Enhancing and Measuring Consumers’ Motivation, Opportunity, and Ability to Process Brand Information from Ads. J. Mark. 1991, 55, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cummings, L.L.; Schwab, D.P. Performance in Organizations: Determinants and Appraisal; Management applications series; Glenview, Ill. [u.a.]: Scott, Foresman and Co.: Brookfield, IL, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Siemsen, E.; Roth, A.V.; Balasubramanian, S. How motivation, opportunity, and ability drive knowledge sharing: The constraining-factor model. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 26, 426–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, X.Y.; Bai, B. How Motivation, Opportunity, and Ability Impact Travelers’ Social Media Involvement and Revisit Intention. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, M.; Pringle, C.D. The Missing Opportunity in Organizational Research: Some Implications for a Theory of Work Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.S.; Friend, S.B. Contingent cross-selling and up-selling relationships with performance and job satisfaction: An MOA-theoretic examination. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2015, 35, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, H.E.; Murtic, A.; Zander, U.; Richtnér, A. What Fosters Individual-Level Absorptive Capacity in MNCs? An Extended Motivation–Ability–Opportunity Framework. Manag. Int. Rev. 2019, 59, 93–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ekmekcioglu, E.B.; Aydintan, B.; Celebi, M. The effect of charismatic leadership on coordinated teamwork: A study in Turkey. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 1051–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Henderson, A.M.; Parsons, T. The Theory of Social and Economic Organization; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Den Hartog, D.N.; Koopman, P.L.; Van Muijen, J.J. Charismatic Leadership; A State of the Art. J. Leadersh. Stud. 1995, 2, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.B.; Birkinshaw, J. The Antecedents, Consequences, and Mediating Role of Organizational Ambidexterity. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, M.E.; Trevino, L.K. Socialized charismatic leadership, values congruence, and deviance in work groups. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Patterson, P.G.; de Ruyter, K. Achieving Service-Sales Ambidexterity. J. Serv. Res. 2013, 16, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erez, A.; Misangyi, V.F.; Johnson, D.E.; LePine, M.A.; Halverson, K.C. Stirring the Hearts of Followers: Charismatic Leadership as the Transferal of Affect. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ashill, N.J.; Rod, M.; Carruthers, J. The effect of management commitment to service quality on frontline employees’ job attitudes, turnover intentions and service recovery performance in a new public management context. J. Strateg. Mark. 2008, 16, 437–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruyter, K.; Keeling, D.I.; Yu, T. Service-Sales Ambidexterity: Evidence, Practice, and Opportunities for Future Research. J. Serv. Res. 2020, 23, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, A.S. The impact of service failures on customer loyalty: The moderating role of affective commitment. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2004, 15, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasmand, C.; Blazevic, V.; de Ruyter, K. Generating Sales While Providing Service: A Study of Customer Service Representatives’ Ambidextrous Behavior. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weitz, B.A.; Sujan, H.; Sujan, M. Knowledge, Motivation, and Adaptive Behavior: A Framework for Improving Selling Effectiveness. J. Mark. 1986, 50, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, R.; Das, G. The impact of job satisfaction, adaptive selling behaviors and customer orientation on salesperson’s performance: Exploring the moderating role of selling experience. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2013, 28, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasmand, C.; Blazevic, V.; Ruyter, K. de Cross-selling in service recovery encounters—Staying under the customer’s radar to avoid salesperson stereotype activation. In Proceedings of the AMA Winter Conference Proceedings, St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 17–19 February 2012; pp. 276–277. [Google Scholar]

- Sujan, H.; Weitz, B.A.; Kumar, N. Learning Orientation, Working Smart, and Effective Selling. J. Mark. 2018, 58, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cron, W.L.; Marshall, G.W.; Singh, J.; Spiro, R.L.; Sujan, H. Salesperson selection, training, and development: Trends, implications, and research opportunities? J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2005, 25, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.-E.; Lee, Y.-H.; Hsu, J.-W. Does Service Recovery Really Work? The Multilevel Effects of Online Service Recovery Based on Brand Perception. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, F.; Locander, W.B.; Spector, P.E.; Harris, E.G. Getting the job done: The moderating role of initiative on the relationship between intrinsic motivation and adaptive selling. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2007, 27, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, S.; Iacobucci, D. Antecedents and consequences of adaptive selling confidence and behavior: A dyadic analysis of salespeople and their customers. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 38, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J. Evaluating Service Encounters: The Effects of Physical Surroundings and Employee Responses. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabnis, G.; Chatterjee, S.C.; Grewal, R.; Lilien, G.L. The Sales Lead Black Hole: On Sales Reps’ Follow-Up of Marketing Leads. J. Mark. 2013, 77, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mom, T.J.M.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Cholakova, M.; Jansen, J.J.P. A Multilevel Integrated Framework of Firm HR Practices, Individual Ambidexterity, and Organizational Ambidexterity. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 3009–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lorincová, S.; Štarchoň, P.; Weberová, D.; Hitka, M.; Lipoldová, M. Employee Motivation as a Tool to Achieve Sustainability of Business Processes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edgar, F.; Blaker, N.M.; Everett, A.M. Gender and job performance: Linking the high performance work system with the ability–motivation–opportunity framework. Pers. Rev. 2021, 50, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiue, W.; Tuncdogan, A.; Wang, F.; Bredican, J. Strategic enablers of service-sales ambidexterity: A preliminary framework and research agenda. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 92, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Analysis, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Publishers: Hlilsdale, NJ, USA, 1992; ISBN 0805810625. [Google Scholar]

- Irfan, M.; Akhtar, N.; Ahmad, M.; Shahzad, F.; Elavarasan, R.M.; Wu, H.; Yang, C. Assessing public willingness to wear face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic: Fresh insights from the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Panagopoulos, N.G.; Rapp, A.A. Feeling Good by Doing Good: Employee CSR-Induced Attributions, Job Satisfaction, and the Role of Charismatic Leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Elavarasan, R.M.; Hao, Y.; Feng, M.; Sailan, D. An assessment of consumers’ willingness to utilize solar energy in china: End-users’ perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 126008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Hao, Y.; Ikram, M.; Wu, H.; Akram, R.; Rauf, A. Assessment of the public acceptance and utilization of renewable energy in Pakistan. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 27, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Li, H.; Rehman, A. The influence of consumers’ intention factors on willingness to pay for renewable energy: A structural equation modeling approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 21747–21761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbach, N.; Ahlemann, F. Structural Equation Modeling in Information Systems Research Using Partial Least Squares. J. Inf. Technol. Theory Appl. 2010, 11, 5–40. [Google Scholar]

- Irfan, M.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Rehman, A.; Ozturk, I.; Li, H. Consumers’ intention-based influence factors of renewable energy adoption in Pakistan: A structural equation modeling approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 28, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, A.; Zeng, S.; Irfan, M. Do Perceived Risk, Perception of Self-Efficacy, and Openness to Technology Matter for Solar PV Adoption? An Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Energies 2021, 14, 5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Shahid, A.L.; Ahmad, M.; Iqbal, W.; Elavarasan, R.M.; Ren, S.; Hussain, A. Assessment of public intention to get vaccination against COVID-19: Evidence from a developing country. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 566–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Rather, R.A.; Iqbal, M.K.; Bhutta, U.S. An assessment of corporate social responsibility on customer company identification and loyalty in banking industry: A PLS-SEM analysis. Manag. Res. Rev. 2020, 43, 1337–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, M.; Faraz, N.A.; Ahmed, F.; Raza, A. How does servant leadership foster employees’ voluntary green behavior? A sequential mediation model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arbuckle, J.L. IBM SPSS Amos 21: User’s Guide. Available online: https://www.sussex.ac.uk/its/pdfs/Amos_20_User_Guide.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; Akhtar, N.; Jabeen, G.; Irfan, M.; Anser, M.K.; Wu, H.; Isek, C. Intention-based critical factors affecting willingness to adopt Novel Coronavirus prevention in Pakistan: Implications for future pandemics. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Saraf, N.; Hu, Q.; Xue, Y. Assimilation of enterprise systems: The effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 31, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Van Oppen, C. Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2009, 33, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.M.; Klein, K.; Wetzels, M. Hierarchical Latent Variable Models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for Using Reflective-Formative Type Models. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 359–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmöller, J.-B. Latent Variable Path Modeling with Partial Least Squares; Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Ketchen, D.J.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Calantone, R.J. Common Beliefs and Reality About PLS. Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Adv. Int. Mark. 2009, 20, 277–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 9780805802832. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcelin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henseler, J.; Chin, W.W. A comparison of approaches for the analysis of interaction effects between latent variables using partial least squares path modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. 2010, 17, 82–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nijssen, E.J.; Guenzi, P.; van der Borgh, M. Beyond the retention—acquisition trade-off: Capabilities of ambidextrous sales organizations. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 64, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, A.; De Ruyter, K. Adaptive versus proactive behavior in service recovery: The role of self-managing teams. Decis. Sci. 2004, 35, 457–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chang, Y.Y.; Chang, C.Y.; Chen, C.W.; Chen, Y.C.K.; Chang, S.Y. Firm-level participative leadership and individual-level employee ambidexterity: A multilevel moderated mediation analysis. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 561–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, F. Ambidextrous leadership, ambidextrous employee, and the interaction between ambidextrous leadership and employee innovative performance. J. Innov. Entrep. 2018, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qammar, R.; Abidin, R.Z.U. Mediating and Moderating Role of Organizational Ambidexterity and Innovative Climate among Leadership Styles and Employee Performance. J. Manag. Info. 2020, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannetti, M.; Cardinali, S.; Sharma, P. Sales technology and salespeople’s ambidexterity: An ecosystem approach. J. Bus. & Ind. Mark. 2020, 36, 615–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, A.A.; Bachrach, D.G.; Flaherty, K.E.; Hughes, D.E.; Sharma, A.; Voorhees, C.M. The Role of the Sales-Service Interface and Ambidexterity in the Evolving Organization. J. Serv. Res. 2017, 20, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Range | Features | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 286 | 83 |

| Female | 58 | 17 | |

| Education | Bachelor | 184 | 53.4 |

| Master | 52 | 15.1 | |

| MS/M.Phil. | 42 | 12.2 | |

| Others | 66 | 19.1 | |

| Age | 20–25 | 83 | 24.1 |

| 26–30 | 105 | 30.5 | |

| 31–35 | 63 | 18.2 | |

| 36–40 | 57 | 16.5 | |

| 41–45 | 21 | 6.2 | |

| More than 45 years | 15 | 4.5 | |

| Representative industry | Pharmaceuticals | 111 | 32.2 |

| Banking | 77 | 22.5 | |

| Telecommunication | 92 | 26.7 | |

| Information technology | 64 | 18.6 | |

| Sales experience | Less than 1 year | 14 | 4.2 |

| 1–5 years | 133 | 38.5 | |

| 6–10 years | 155 | 45.1 | |

| 11–15 years | 30 | 8.8 | |

| More than 15 years | 12 | 3.5 |

| Constructs | CL | MTV | OPR | ABL | SSA | ASB | SRP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL | 0.738 | ||||||

| MTV | 0.606 | 0.778 | |||||

| OPR | 0.551 | 0.564 | 0.801 | ||||

| ABL | 0.428 | 0.611 | 0.355 | 0.864 | |||

| SSA | 0.688 | 0.519 | 0.664 | 0.676 | 0.783 | ||

| ASB | 0.670 | 0.715 | 0.713 | 0.472 | 0.613 | 0.769 | |

| SRP | 0.677 | 0.656 | 0.666 | 0.555 | 0.522 | 0.652 | 0.750 |

| Constructs | Indicators | Substantive Factor Loading (R1) | R12 | Method Factor Loading (R2) | R22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charismatic leadership | CL1 | 0.768 | 0.590 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| CL2 | 0.976 | 0.953 | −0.155 | 0.024 | |

| CL3 | 0.914 | 0.835 | −0.190 | 0.036 | |

| CL4 | 0.532 | 0.283 | 0.225 | 0.051 | |

| CL5 | 0.913 | 0.834 | −0.163 | 0.027 | |

| CL6 | 0.880 | 0.774 | −0.098 | 0.010 | |

| CL7 | 0.858 | 0.736 | −0.217 | 0.047 | |

| CL8 | 0.894 | 0.799 | −0.098 | 0.010 | |

| CL9 | 0.812 | 0.659 | 0.463 | 0.214 | |

| CL10 | 0.681 | 0.464 | 0.381 | 0.145 | |

| Service-sales ambidexterity | SSA1 | 0.703 | 0.494 | 0.005 | 0.000 |

| SSA2 | 0.685 | 0.469 | 0.061 | 0.004 | |

| SSA3 | 0.956 | 0.914 | −0.320 | 0.102 | |

| SSA4 | 0.760 | 0.578 | −0.113 | 0.013 | |

| SSA5 | 0.967 | 0.935 | −0.268 | 0.072 | |

| SSA6 | 0.921 | 0.848 | −0.167 | 0.028 | |

| SSA7 | 0.564 | 0.318 | 0.244 | 0.060 | |

| SSA8 | 0.600 | 0.360 | 0.099 | 0.010 | |

| SSA9 | 0.801 | 0.642 | −0.207 | 0.043 | |

| SSA10 | 0.658 | 0.433 | 0.311 | 0.097 | |

| SSA11 | 0.555 | 0.308 | 0.453 | 0.205 | |

| Motivation | MTV1 | 0.653 | 0.426 | −0.434 | 0.188 |

| MTV2 | 0.566 | 0.320 | −0.495 | 0.245 | |

| MTV3 | 0.976 | 0.953 | 0.192 | 0.037 | |

| MTV4 | 0.911 | 0.830 | 0.213 | 0.045 | |

| MTV5 | 0.946 | 0.895 | 0.151 | 0.023 | |

| MTV6 | 0.815 | 0.664 | 0.239 | 0.057 | |

| Opportunity | OPR1 | 0.796 | 0.634 | 0.019 | 0.000 |

| OPR2 | 0.930 | 0.865 | −0.082 | 0.007 | |

| OPR3 | 0.917 | 0.841 | −0.155 | 0.024 | |

| OPR4 | 0.623 | 0.388 | 0.213 | 0.045 | |

| OPR5 | 0.740 | 0.548 | 0.005 | 0.000 | |

| Ability | ABL1 | 0.865 | 0.748 | −0.003 | 0.000 |

| ABL2 | 0.913 | 0.834 | −0.009 | 0.000 | |

| ABL3 | 0.816 | 0.666 | 0.031 | 0.001 | |

| ABL4 | 0.858 | 0.736 | −0.017 | 0.000 | |

| Adaptive selling behavior | ASB1 | 0.776 | 0.602 | −0.070 | 0.005 |

| ASB2 | 0.975 | 0.951 | −0.152 | 0.023 | |

| ASB3 | 0.799 | 0.638 | 0.029 | 0.001 | |

| ASB4 | 0.672 | 0.452 | 0.193 | 0.037 | |

| ASB5 | 0.614 | 0.377 | −0.022 | 0.000 | |

| Service recovery performance | SRP1 | 0.633 | 0.401 | 0.254 | 0.065 |

| SRP2 | 0.717 | 0.514 | −0.051 | 0.003 | |

| SRP3 | 0.671 | 0.450 | 0.136 | 0.018 | |

| SRP4 | 0.944 | 0.891 | −0.264 | 0.070 | |

| SRP5 | 0.839 | 0.704 | −0.077 | 0.006 | |

| Average | 0.791 | 0.642 | 0.001 | 0.046 |

| Hypothetical Paths | β Estimates | S.E | t-Value | CI. 95% | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | CL→SSA | 0.183 *** | 0.076 | 2.399 | [0.055, 0.355] | Supported |

| H2 | SSA→SRP | 0.543 *** | 0.092 | 5.907 | [0.387, 0.621] | Supported |

| H3 | SSA→ASB | 0.712 *** | 0.090 | 7.911 | [0.654, 0.871] | Supported |

| H4 | ASB→SRP | 0.335 *** | 0.102 | 3.298 | [0.120, 0.514] | Supported |

| Moderation Paths | β Coefficient | SE | t-Value | CI 95% | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H5 | MTV × CL → SSA | 0.275 *** | 0.144 | 1.911 | [0.105, 0.522] | Supported |

| H6 | OPR × CL → SSA | 0.088 ** | 0.067 | 1.304 | [0.093, 0.171] | Supported |

| H7 | ABL × CL → SSA | 0.169 *** | 0.121 | 1.402 | [0.105, 0.522] | Supported |

| H5a | MTV(High) × CL → SSA | 0.322 *** | 0.065 | 4.953 | [0.216, 0.388] | Supported |

| H5b | MTV(Low) × CL → SSA | −0.059 | 0.109 | −0.539 | [−0.275, 0.157] | Not Supported |

| H6a | OPR(High) × CL → SSA | 0.279 *** | 0.052 | 5.365 | [0.177, 0.381] | Supported |

| H6b | OPR(Low) × CL → SSA | 0.133 | 0.149 | 0.891 | [−0.161, 0.428] | Not Supported |

| H7a | ABL(High) × CL → SSA | 0.377 *** | 0.051 | 7.392 | [0.262, 0.469] | Supported |

| H7b | ABL(Low) × CL → SSA | 0.150 | 0.084 | 1.773 | [−0.017, 0.318] | Not Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmad, B.; Da, L.; Asif, M.H.; Irfan, M.; Ali, S.; Akbar, M.I.U.D. Understanding the Antecedents and Consequences of Service-Sales Ambidexterity: A Motivation-Opportunity-Ability (MOA) Framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9675. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179675

Ahmad B, Da L, Asif MH, Irfan M, Ali S, Akbar MIUD. Understanding the Antecedents and Consequences of Service-Sales Ambidexterity: A Motivation-Opportunity-Ability (MOA) Framework. Sustainability. 2021; 13(17):9675. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179675

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmad, Bilal, Liu Da, Mirza Huzaifa Asif, Muhammad Irfan, Shahid Ali, and Muhammad Imad Ud Din Akbar. 2021. "Understanding the Antecedents and Consequences of Service-Sales Ambidexterity: A Motivation-Opportunity-Ability (MOA) Framework" Sustainability 13, no. 17: 9675. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179675

APA StyleAhmad, B., Da, L., Asif, M. H., Irfan, M., Ali, S., & Akbar, M. I. U. D. (2021). Understanding the Antecedents and Consequences of Service-Sales Ambidexterity: A Motivation-Opportunity-Ability (MOA) Framework. Sustainability, 13(17), 9675. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179675