Learning to Leave and to Return: Mobility, Place, and Sense of Belonging amongst Young People Growing up in Border and Rural Regions of Mainland Portugal

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

Place-making mechanisms that serve to constantly (re)construct localities are demonstrated in a range of recurrent discursive practices narrating collective understandings of place and alluding to those felt sensations “beneath” articulated expression. Dominant discursive understandings about place, regionality, and stigmatised place reputation play a role in young people’s place-making practice.[27] (p. 279)

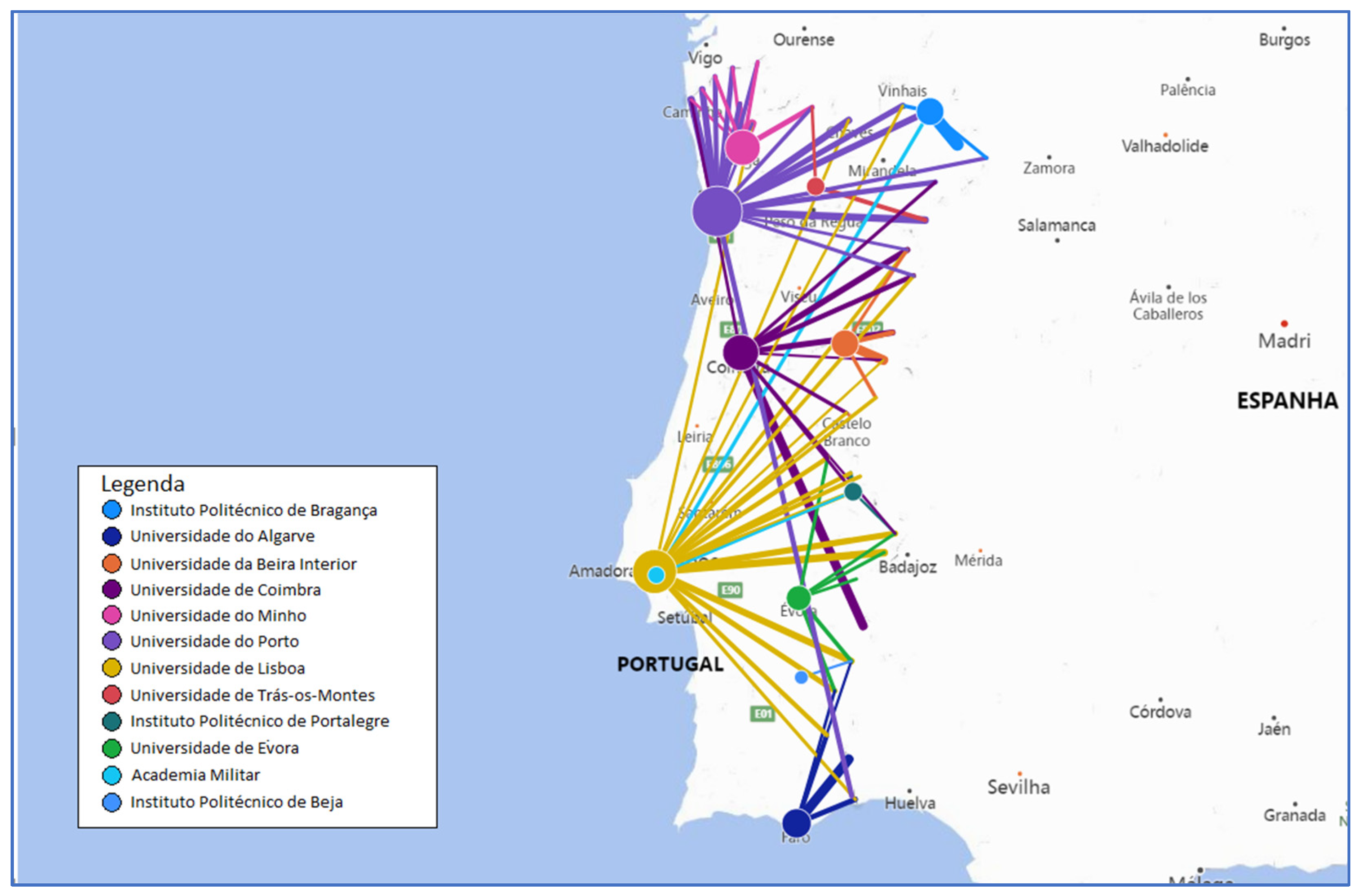

3. The Study

4. Method

Data Analysis

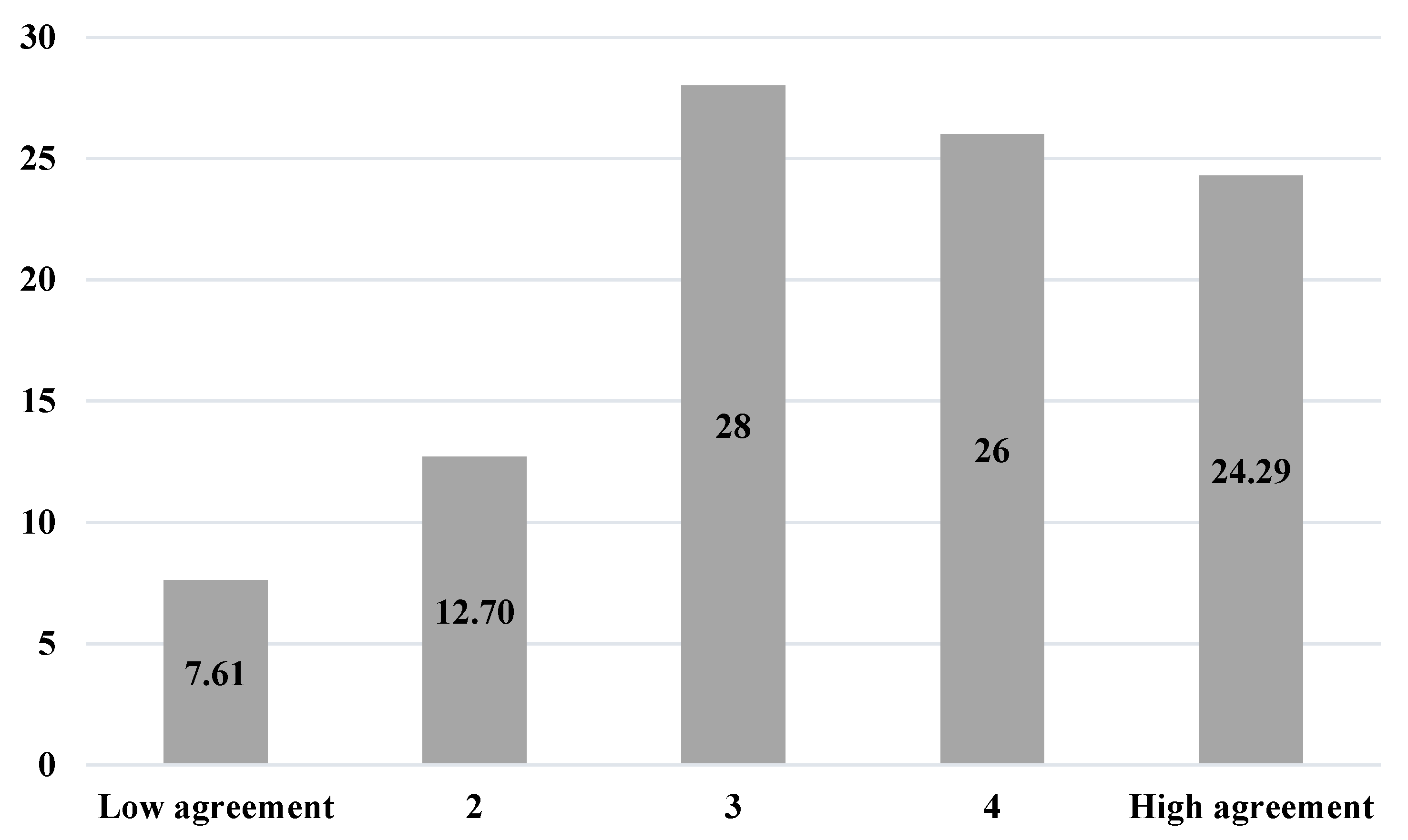

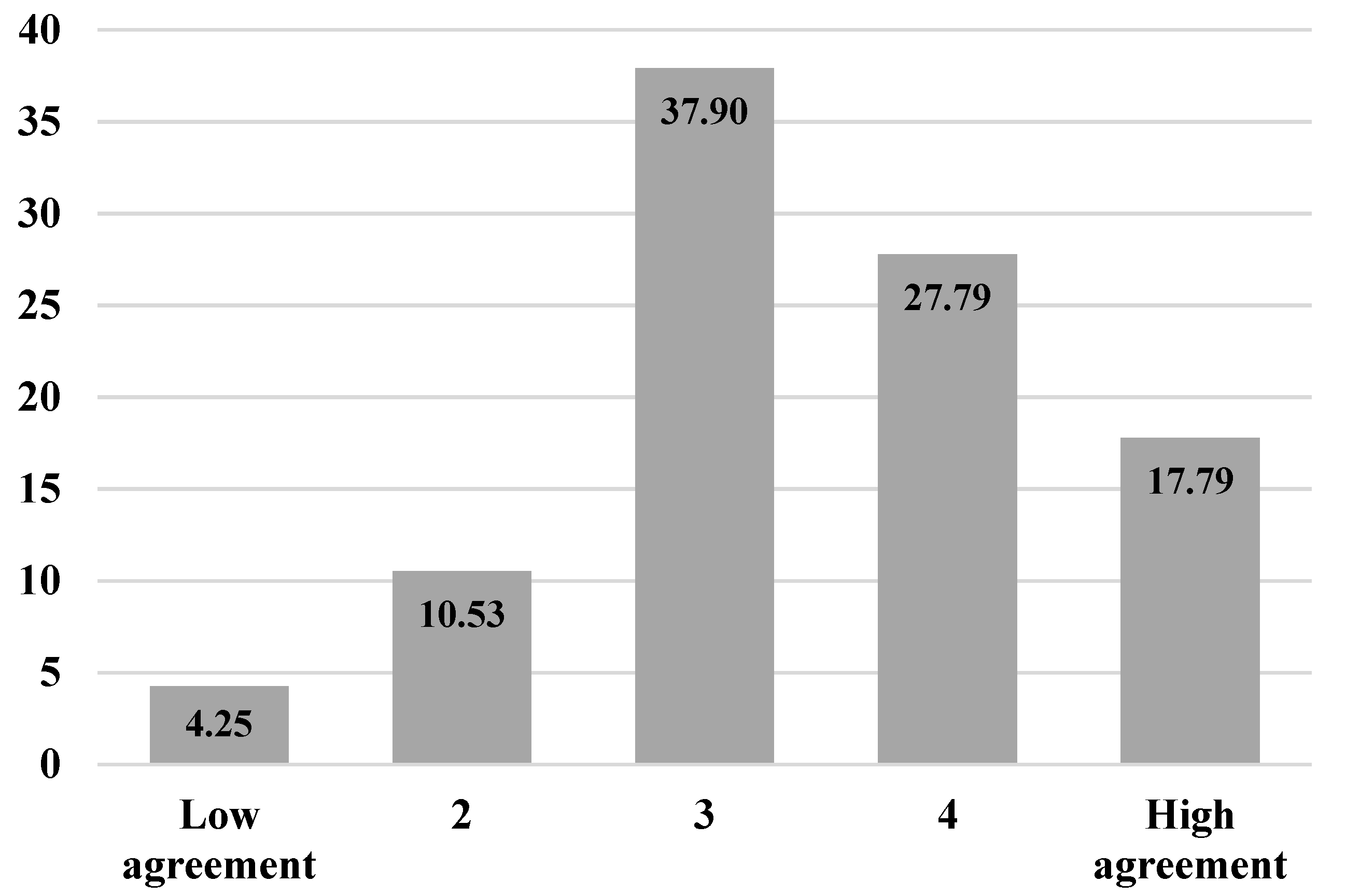

5. Results

5.1. Advantages and Disadvantages of Growing up in Rural Border Regions: The Perspectives of Young People

5.2. Young People’s Expectations and Feelings about Leaving and Returning

I know that the best universities, and the best ones closest to here, are in Minho and Porto, in coastal regions, but despite being “close”, the closest ones end up being quite far, as it always ends up being 300 km. It’s a bit boring.(Girl-BI-North)

Because there are more job opportunities on the coast and also because I don’t want that life here, I don’t want my children, my close family, future living here because I think they can have more opportunities on the coast and in a more developed city.(Boy-FGD-North)

Most of them want to leave. (…) They think they have no life here, no quality of life, I don’t know.

Interviewer: But do you have a different opinion?

I do, I prefer to live here.(Gir-BI-North)

The diversity of vocational programmes that are offered, at least in this school, is not very big. It’s even a little limited, which ends up expelling many students from here. And then later, maybe, they’ll find a job where they went to study and this increases the rural exodus, isn’t it?(Gir-BI-North)

I would also like to leave and study in Porto or Lisbon, but contrary to what they said, I would like to come back to live here, but I don’t think it will be possible.(Girl-FGD-North)

I think that coming back here would be because of family, to be closer to them, but it’s also a quiet place, not so stressful. So, it would also be a positive point, so I think that if I could do here what I like, I could still live here.(Girl-BI-North)

Because I don’t intend to abandon. I intend to leave, but I don’t intend to abandon. I mean, I intend to do things that make me evolve (…). But I don’t intend to leave my homeland, and I intend to come here, bring things, that open the horizons, that give me more opportunities, even to those who stay…(Girl-BI-South)

The connection continues, also because of what I told you at the beginning which has to do with how the community interacts. I’m absolutely sure that everyone who leaves speaks with great pride about CV and we have an occasion that is almost mandatory to return to Castelo de Vide at is Easter.(Municipality-South)

I want to leave this region a little, because I can see myself in a few years coming back here, and to experience something new, so as not to be always in the same place, so that my life does not become so constant.(Girl-BI-North)

The next question that you will ask me is a tricky question for me as a politician, which is, “And then, will young people come back?”. What we realised is that their wish was more the will to stay than to leave, but they felt that there was this need to leave to succeed in professional world.(Municipality-North)

When young people leave, they wish to return, but they do not return because there is no job offer for what they want or because there is not much variety either.(Municipality-South)

There are many young people who would like to settle here, after starting a family here, but then there is no way…(Municipality-North)

Nowadays, they go to higher education, but I think there is one thing that is part of the home region culture, they want to come back. (…) they are in college, but they come to study for the library. (…) that didn’t happen, in my time as a student, that didn’t happen. Our children, our young people, at the weekends and in the exams period, make a point of returning to their home.(Municipality-North)

Our students, one way or the other, they return to their homeland.(Municipality-North)

I’m going to my hometown because I know I can contribute to this, this and that …. And they are very much like that: to give their contribution, we have many young people volunteering, especially up to the 12th grade; we have many young people doing volunteer work, at various levels.(Municipality-North)

Being rooted in associations and traditional music bands makes them say “I’m going to XX, I’ll be there for the exam, but I’ll also have the opportunity to go to the rehearsal, to participate in that activity that I know is scheduled for that day”. So, I think that’s what pulls them, the fact that there is this youth associations’ movement. I think is also a reason for them to come back and especially when they can, which is on the weekend, vacations.(Municipality-North)

But it is what I say, they go to work abroad, but they come back, even if only on weekends and this is already good for us, it is already a recognition of the territory, they are very rooted to the land and this is good, I saw this in my student days, “are you going home? Yes, I insist”, and I was also connected to an association at the time. And I see this exactly in my daughter and she is also in the music band and there is this connection.(Municipality-North)

I don’t know if this is the reason, I’m probably speculating, but they are very close to Castelo de Vide. Many of them are studying abroad and are, for example, members of the municipal assembly here, which means that they want to actively participate in the life and political decisions of the development of the municipality. And so, they have that very strong connection, yes.(Municipality-South)

5.3. “Walk-the-Line” Actions of Municipalities to Promote Young People Settlement

We are here with plenty of future perspectives, both in terms of youth and educational policies, which I think allow people, even if they work in the large urban centres on the coast, to live here and have their children studying here as late as possible, despite working in the coastal areas.(Municipality North)

But we can’t just settle people through cultural offering. We have to have other reasons to make people think “Why not X?”, “Why X, X? Why X?” And we have, over time, made a strong bet on education. Because what did we think? Well, if we give the capacity for the new families, to have a good education, a public and free education, in our municipality, and the City Council, in parallel to what the State already assumes as its own responsibility, is good.(Municipality-North)

Then we have taken advantage of all the possibilities of project applications, whether for the financing of infrastructures or for the financing of the integrated plans to fight school failure. We try, as much as possible, to create these types of mechanisms.(Municipality-North)

When they extended compulsory education to the 12th grade, the legislation regarding transportation did not follow, that is, education was compulsory, but the municipality was not obliged to provide transportation. However, we decided that it was. We had to keep up.(Municipality-North)

Answering your question specifically, do the young people stay? I believe that those who have the opportunity and the possibility to stay here, stay. Are they as many as we would like? They are not. Is the day-to-day work that we do here to create these opportunities and create the necessary synergies for these people to stay here? Yes. We want our young people to stay, we don’t want them to immigrate, to leave.(Municipality-North)

Our biggest concern is essentially, in the first place, to empower our young people; to make them aware of the instruments that they can use to be successful (…) essentially, what we seek is to take advantage of all the opportunities that governments give us to develop our region. Ok, essentially, we are very pragmatic. Let’s say, we invest practically all of our budget in applications to bring more value to our municipality.(Municipality-North)

When people come here, they already have a little notion of what is waiting for them, (…) we have reduced rates or total exemption of IMI rates for young people, i.e., young couples or single people who want to buy a house are exempt from taxes, we have the rental with rent assistance.(Municipality-North)

We see that people are trying and insisting. That is, there is no desire to leave and abandon the region, but the resources are not what we want.(Municipality-North)

Here in the City Council, we work to create conditions so that all people, and young people…, especially young people, identify with the territory, that they care about the population and their well-being; and invest in offering settlement options. But it is now obvious that city councils don’t have the capacity to do this on their own. What we are trying to do is unblock some situations; talk to the responsible bodies, try to work together to make it possible to create other conditions here. But if there is not really a will for the common good of all the parties involved, it is difficult, because what we have seen lately is also the closure of public services in these territories.(Municipality-South)

This is intended, but of course the issue of employment is also very important, and the City Council has here, and the City Council has also invested a lot in trying to establish companies here and that create employment opportunities here.(Municipality-North)

That’s why we will design a business plan, but we always wanted to work on these two poles, the issue of employability for students—we saw that many do not continue their studies—and to do work with local entrepreneurs.(Municipality-South)

And if you motivate the young people, as they feel this affection, this attention that they have for the region, for this kind of projects, it is a very good advantage.(Municipality-North)

It takes a lot of love to be able to stay; to insist on staying in the region, but those who stay, without any doubt, stay because of that love and end up really concluding that there is no place where you can have a better quality of life than here.(Municipality-North)

Place-making mechanisms encompass an active engagement demonstrated in talk concerning place. Simultaneously, place-making is a process that occurs beneath rational articulations demonstrated in verbally expressed interpretations of material place as sensed, emotive, and experiential.[27] (p. 277)

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item | Mean (M) | SD (Standard Deviation) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | This region limits my life opportunities. | 3.47 | 1.21 |

| 2 | There are advantages in living in the inlands. | 3.45 | 1.04 |

| 3 | In my region there is a strong investment in education. | 3.04 | 1.01 |

| 4 | In my region there exists a lot of employment opportunities. | 2.50 | 1.01 |

| 5 | In my region there are many youth support services. | 2.77 | 0.99 |

| 6 | My future will always imply leaving this region. | 3.44 | 1.19 |

| 7 | If I have to leave my region, I will always return. | 3.29 | 1.29 |

| 8 | When I think about the future, I always think about studying or working in another region. | 3.75 | 1.17 |

| 9 | I wish I could continue my studies in this region. | 2.64 | 1.34 |

| 10 | I’m only thinking of going into higher education if it’s to an institution in this region. | 1.63 | 0.94 |

| 11 | I feel that I belong to my community. | 3.99 | 1.05 |

| 12 | As a young person. I have a lot to give to the region where I grew up. | 3.25 | 1.12 |

| 13 | After the 12th grade, I intend to go into higher education | 4.13 | 1.31 |

| 14 | After the 12th grade I intend to start work. | 2.58 | 1.41 |

References

- Corbett, M. Learning to Leave: The Irony of Schooling in a Coastal Community. Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, P.; Green, B. Researching Rural Places. Qual. Inq. 2013, 19, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, A. Regimes of youth transitions: Choice, flexibility and security in young people’s experiences across different European contexts. Young 2006, 14, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haukanes, H. Belonging, Mobility and the Future: Representations of Space in the Life Narratives of Young Rural Czechs. Young 2013, 21, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrbis, Z.; Woodward, I.; Bean, C. Seeds of cosmopolitan future? Young people and their aspirations for future mobility. J. Youth Stud. 2013, 17, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silva, S.M. Growing up in a Portuguese borderland. In Children and Borders; Spyrou, S., Christou, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2014; pp. 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia, D. The mobility imperative for rural youth: The structural, symbolic and non-representational dimensions rural youth mobilities. J. Youth Stud. 2016, 19, 836–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, D. Class, place and mobility beyond the global city: Stigmatisation and the cosmopolitanisation of the local. J. Youth Stud. 2019, 23, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C. Moving away or staying local: The role of locality in young people’s ’spatial horizons’ and career aspirations. J. Youth Stud. 2016, 19, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corbett, M. Rural Futures: Development, Aspirations, Mobilities, Place, and Education. Peabody J. Educ. 2016, 91, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.; Ferrante, L.; Soler-Porta, M. There is No Place like Home! How Willing Are Young Adults to Move to Find a Job? Sustainability 2021, 13, 7494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, J.; Arco-Tirado, J.L.; Caserta, M.; Cemalcilar, Z.; Freitag, M.; Hörisch, F.; Jensen, C.; Kittel, B.; Littvay, L.; Lukeš, M.; et al. Perceived economic self-sufficiency: A country- and generation-comparative approach. Eur. Politi. Sci. 2018, 18, 510–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M.S. More-than-Representational Knowledge/s of the Countryside: How We Think as Bodies. Sociol. Rural 2008, 48, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Performing rurality and practising rural geography. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2010, 34, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, M. Towards a rural sociological imagination: Ethnography and schooling in mobile modernity. Ethnogr. Educ. 2015, 10, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, R. Using southern theory: Decolonizing social thought in theory, research and application. Plan. Theory 2014, 13, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokland, T. Celebrating Local Histories and Defining Neighbourhood Communities: Place-making in a Gentrified Neighbourhood. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 1593–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.F. Space and Place. The Perspective of Experience; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, UK; London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction. A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia, D.; Smyth, J.; Harrison, T. Affective Topologies of Rural Youth Embodiment. Sociol. Rural 2015, 56, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, D.; Growiec, K.; Smyth, J. Leaving Northern Ireland: Youth mobility field, habitus and recession among undergraduates in Belfast. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2013, 34, 544–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, D. I wouldn’t want to stay here: Economic crisis and youth mobility in Ireland. Int Migr. 2014, 52, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, H.D. Is out of Sight out of Mind? Place Attachment among Rural Youth Out-Migrants. Sociol. Rural 2018, 58, 684–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, D.; Smyth, J.; Harrison, T. Emplacing young people in an Australian rural community: An extraverted sense of place in times of change. J. Youth Stud. 2014, 17, 1152–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, D.; Smyth, J.; Harrison, T. Rural young people in late modernity: Place, globalisation and the spatial contours of identity. Curr. Sociol. 2014, 62, 1036–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiborg, A. Place, Nature and Migration: Students’ Attachment to their Rural Home Places. Sociol. Rural 2004, 44, 416–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, C. Young People’s Place-Making in a Regional Australian Town. Sociol. Rural 2017, 58, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, C. Making place with mobile media: Young people’s blurred place-making in regional Australia. Mob. Media Commun. 2019, 8, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlkvist, J.A.; Urry, J. Sociology beyond Societies: Mobilities for the Twenty-First Century. Teach. Sociol. 2000, 28, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, N.G.; Salazar, N.B. Regimes of Mobility across the Globe. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2013, 39, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, M.; Urry, J. (Eds.) Mobilities: New Perspectives on Transport and Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shildrick, T. Youth culture, subculture and the importance of neighbourhood. Young 2006, 14, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, T. Young People’s Urban Im/Mobilities: Relationality and Identity Formation. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Cuervo, H. Staying, leaving and returning: Rurality and the development of reflexivity and motility. Curr. Sociol. 2020, 68, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, A.; Cartmel, F. Young People and Social Change; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Morano-Foadi, S. Scientific Mobility, Career Progression, and Excellence in the European Research Area1. Int. Migr. 2005, 43, 133–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, D. Moving in transition: Northern Ireland youth and geographical mobility. Young 2008, 16, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, L. Migration, Place and Class: Youth in a Rural Area. Sociol. Rev. 2000, 48, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, R.; Taylor, R. Between cosmopolitanism and the locals: Mobility as a resource in the transition to adulthood. Young 2005, 13, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, T. Towards a Politics of Mobility. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2010, 28, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaufmann, V.; Bergman, M.M.; Joye, D. Motility: Mobility as capital. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2004, 28, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faus, M.M. Dibujando la (in)movilidad: Potencial y limitaciones de una técnica participativa centrada en la infancia. Soc. Infanc. 2021, 5, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalir, B. Moving Subjects, Stagnant Paradigms: Can the ‘Mobilities Paradigm’ Transcend Methodological Nationalism? J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2013, 39, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J. Does mobility have a future? In Mobilities: New Perspectives on Transport and Society, 1st ed.; Grieco, M., Urry, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Skeggs, B. Class, Self, Culture; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, D.C. Mapping the Youth Mobility Field. In Handbuch Kindheits und Jugendsoziologie; Lange, A., Reiter, H., Schutter, S., Steiner, C., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 463–478. [Google Scholar]

- Sheller, M. Automotive Emotions. Theory Cult. Soc. 2004, 21, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomley, N.K. Mobility, empowerment and the rights revolution1. Politi. Geogr. 1994, 13, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, T. Mobilities: An Introduction. New Form. 2001, 43, 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sheller, M.; Urry, J. The New Mobilities Paradigm. Environ. Plan A Econ. Space 2006, 38, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bærenholdt, J.O.; Granås, B. Mobility and Place: Enacting Northern European Peripheries, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Leyshon, M. The struggle to belong: Young people on the move in the countryside. Popul. Space Place 2009, 17, 304–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, H.; Wyn, J. A Longitudinal Analysis of Belonging: Temporal, performative and relational practices by young people in rural Australia. Young 2017, 25, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, N.G.; Norman, M.E.; Dupré, K. Rural youth and emotional geographies: How photovoice and words-alone methods tell different stories of place. J. Youth Stud. 2014, 17, 1114–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J.G., Ed.; Greenwood Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N. Inequality in Social Capital. Contemp. Sociol. A J. Rev. 2000, 29, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N. Social Networks and Status Attainment. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1999, 25, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A. Regions unbound: Towards a new politics of place. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2004, 86, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baylina, M.; Villarino, M.; Garcia Ramon, M.D.; Mosteiro, M.J.; Porto, A.M.; Salamaña, I. Género e innovación en los nuevos procesos de re-ruralización en España. Finisterra 2019, 54, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylina, M.; Rodó-Zárate, M. Youth, activism and new rurality: A feminist approach. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 79, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, M.; Silva, S.M. Youth policies priorities: Understanding young people pathways in border regions of Portugal. Rev. Estud. Reg. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Direção-Geral de Agricultura e Desenvolvimento Rural [DGADR]. Estatuto to Jovem Empresário Rural [Young Rural Entre-preneur Statute]. Available online: https://www.dgadr.gov.pt/estatuto-do-jovem-empresario-rural-jer (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Simões, F. How to involve rural NEET youths in agriculture? Highlights of an untold story. Community Dev. 2018, 49, 556–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.M.; Silva, A.M. School Population Survey: Young People, Education and Border Regions. Questionnaire Approved by the Portuguese Directorate-General for Education, through the System of Monitoring Research in Education Environments (MIME 0566300001). 2016. Available online: http://mime.dgeec.mec.pt/InqueritoConsultar.aspx?id=6699 (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics: And Sex and Drugs and Rock “N” Roll, 4th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo, H.; Wyn, J. Reflections on the use of spatial and relational metaphors in youth studies. J. Youth Stud. 2014, 17, 901–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahelma, E.; Gordon, T. Home as a Physical, Social and Mental Space: Young People’s Reflections on Leaving Home. J. Youth Stud. 2003, 6, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzzocrea, V. ‘Rooted mobilities’ in young people’s narratives of the future: A peripheral case. Curr. Sociol. 2018, 66, 1106–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gabriel, M. Australia’s regional youth exodus. J. Rural Stud. 2002, 18, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, D. Spaces of Youth, Work, Citizenship and Culture in a Global Context; Routledge: Abingdon, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brereton, F.; Bullock, C.; Clinch, J.P.; Scott, M. Rural change and individual well-being: The case of Ireland and rural quality of life. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2011, 18, 203–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dillabough, J.; Kennelly, J. Lost Youth in the Global City: Class, Culture, and the Urban Imaginary; Routledge: Falmer, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.L.; Sassen, S. Cities in a World Economy. Teach. Sociol. 1995, 23, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nóvoa, A. ’A Country on Wheels’: A Mobile Ethnography of Portuguese Lorry Drivers. Environ. Plan A Econ. Space 2014, 46, 2834–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Valid Answers | Boys | Girls | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advantages | 1610 | Related to quality of life (nature, less traffic, less stress) | 631 | 359 | 990 |

| Related to culture and community interactions (significant relationships, shared heritage and history) | 252 | 168 | 620 | ||

| Disadvantages | 1377 | Disadvantages related to local specificities (lack of privacy, distance from urban centres) | 270 | 399 | 669 |

| Disadvantages regarding lack of opportunities (education, employment, etc.) | 283 | 425 | 708 | ||

| Total | 2750 |

| Items | Female (n = 2141) M(SD) | Male (n = 1824) M(SD) | Total M(SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| After the 12th grade I intend to go to higher education. | 4.38(1.14) | 3.84(1.43) | 4.13(1.31) |

| After the 12th grade I intend to start work. | 2.44(1.34) | 2.75(1.43) | 2.58(1.41) |

| Items | Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| When I think about the future, I always think about studying or working in another region. | 3.75 | 1.17 |

| I wish I could continue my studies in this region. | 2.64 | 1.34 |

| I’m only thinking of going into higher education if it’s to an institution in this region. | 1.63 | 0.94 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, S.M.d.; Silva, A.M.; Cortés-González, P.; Brazienė, R. Learning to Leave and to Return: Mobility, Place, and Sense of Belonging amongst Young People Growing up in Border and Rural Regions of Mainland Portugal. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9432. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169432

Silva SMd, Silva AM, Cortés-González P, Brazienė R. Learning to Leave and to Return: Mobility, Place, and Sense of Belonging amongst Young People Growing up in Border and Rural Regions of Mainland Portugal. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):9432. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169432

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Sofia Marques da, Ana Milheiro Silva, Pablo Cortés-González, and Rūta Brazienė. 2021. "Learning to Leave and to Return: Mobility, Place, and Sense of Belonging amongst Young People Growing up in Border and Rural Regions of Mainland Portugal" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 9432. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169432

APA StyleSilva, S. M. d., Silva, A. M., Cortés-González, P., & Brazienė, R. (2021). Learning to Leave and to Return: Mobility, Place, and Sense of Belonging amongst Young People Growing up in Border and Rural Regions of Mainland Portugal. Sustainability, 13(16), 9432. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169432