1. Introduction

Recent literature on African rural youth has emphasized the importance of entrepreneurial culture for rural youth [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In this context, entrepreneurship in rural areas is conceived as a key part of rural development to create employment opportunities for young people, as it tackles their migration at its root causes [

6]. Presently, empirical studies pay special attention to entrepreneurship among African youth in rural areas through the opportunities offered by the agricultural sector or the large numbers of young people that continue to live in rural areas, focusing on the youth unemployment problem [

3]. Although entrepreneurial activity is not the only way to reduce youth unemployment and create income-generating activities, it is certainly one of the essential elements and a fundamental requirement. Today, policymakers in many African countries, including Morocco, have widely acknowledged the role of rural entrepreneurship as the engine of rural development [

7]. Recent research on entrepreneurship has focused largely on motivation that includes items, each covering potentially different motivations. Several motives exist for undertaking an entrepreneurial venture [

8]. Some studies distinguish between innovative and non-innovative entrepreneurial activities by placing the innovative entrepreneur at the heart of the dynamics of capitalism [

9].

The development of the cooperative movement has emerged as an important, interesting, and challenging consideration in public institutions. These various institutions intervene in socioeconomic programs. Each of them carries out actions to achieve specific objectives, but the results have been less than impressive [

10]. In fact, many public institutions that assist small farmer organizations prove to be, in the absence of rigorous scrutiny and evaluation of entrepreneurial difficulties, a source of constraints that limit the impact of public actions believed to be in favor of these organizations. The weak results posted by a number of agricultural aggregation projects still constitute huge constraints for cooperatives’ development. Although the impact of the Green Plan of Morocco on rural development and the cooperative sector has been evaluated, despite the extensive literature suggesting adaptations to avoid negative impacts, there has been less examination of failure resulting from entrepreneurial capacity. This paper focuses on how entrepreneurial intention of women and men affects the success or failure of policies and programs.

Other studies distinguish between opportunity and necessity in entrepreneurship activities. Capital investment tends to play a more important role in the opportunity for entrepreneurship, while drawing on economic opportunities or simply seeking autonomy. In the context of limited financial capital resources, simple unemployment, or general dissatisfaction with the current situation, more of the youth are willing to exhibit increased motivation [

11]. In rural areas, young people have low intentions of becoming entrepreneurs in agriculture due to project financing factors, which involve substantial capital investments and are subject to a high level of risk [

12]. Further research has shown that the attitude factor also influences the intentions of youth entrepreneurship in the agricultural sector. Other factors such as entrepreneurial perceptions, which differ according to their degree of importance as well as their scale of impact, can explain why some of the rural youth, but not others, choose to become entrepreneurs. The perceptions and intentions can be linked to individual perceptions, such as self-efficacy, socio-culture, especially the social legitimation of entrepreneurship, and perceptions about opportunities, where entrepreneurs discover and exploit opportunities which promote the development process [

13,

14,

15,

16].

Social learning factors can be identified as individual perceptions affecting entrepreneurial intentions among the youth that reflect their entrepreneurial attractiveness [

17]. Many empirical studies have been conducted on the perceptions of young people living in the countryside and in urban areas, both young graduates and young illiterate workers, to explain the reasons why youth create businesses [

17]. However, there is no extensive empirical research on factors that influence entrepreneurial intentions of young members of agricultural cooperatives.

Furthermore, agricultural cooperatives are becoming increasingly important for the social, environmental, and economic fabric of rural areas. According to [

18], the vertical coordination of cooperatives is the appropriate vehicle to reduce transaction costs and link smallholder farmers to markets. Thus, cooperatives are considered to be information workspaces for members, i.e., they provide various services involved in the production and sales process, to generate greater profits by obtaining input factors and services from the upstream and downstream supply chain [

19]. In other words, cooperatives stimulate transactions to minimize the various stages of the value chain, help agricultural producers become participants, and increase their share of the benefits [

20].

In fact, since the creation of the Moroccan Office for the Development of Cooperation (ODCO) in 1963, agricultural cooperatives have played an important role in rural development, as they guaranteed the rural population their legitimate right to collaborative work with a view to improving the economic and social situation. Cooperative societies are an appropriate solution for rural youth and women who both have no resources and lack financial capital as well as access to land.

In recent years, policymakers are increasingly encouraging the development of rural entrepreneurship to revitalize rural communities across Morocco [

21]. In addition, these cooperatives and youth entrepreneurship, in particular, are the key engines to sustainable growth in the future because of the potential of the youth to make a great contribution to agribusiness and rural economic activities [

22]. At the same time, youth unemployment is a major problem in Morocco, whether in urban or rural areas. The present challenge lies simultaneously in creating jobs for the bulging youth population and satisfying the expectations of young people and society alike. Youth employment and matching skills are essential components for economic and social stability.

Despite government policies, economic growth has not translated into the creation of decent jobs. The employment rate decreased from 47% to 46.7% [

23] between 2016 and 2017. Furthermore, even if the Government of Morocco and various development partners focus on the rural youth employment challenge regarding the support of small enterprise development, systemic challenges persist for these young people, such as a lack of access to finance, business training, and mentoring. There is a lack of specialized programs to support young entrepreneurs in rural and remote contexts. In recognition of youth’s low interest, the Moroccan Government launched a massive new Integrated Program for Enterprise Support and Financing [

24], with the aim of developing the agricultural sector through incorporating entrepreneurship activities, answering rural youth unemployment, and encouraging the emergence of a rural middle class. Accordingly, the interest rate will be 1.75%, despite the higher credit risk arising from the narrow market, weather vagaries, and large variations in the prices of agricultural products [

25]. An initial assessment of the program is necessary to discover how successful the program has been in its ability to increase business intentions in the first year.

The guarantee of long-term sustainability of rural enterprises requires the youth to develop specific capabilities and competencies, among which entrepreneurial competencies [

7] are the most important. Moreover, the development of innovative rural youth in management, marketing, and business is likely grown along with the work life inclusion that is expected to continue. The development of rural entrepreneurship can be profoundly influenced by close attention to the diversity of the experience acquired by young people in agricultural cooperatives. If rural youth are empowered by entrepreneurial competencies, their intention to establish businesses in rural areas will be strengthened. However, empirical investigations recently conducted have not adequately addressed, within an integrated framework, the questions as to what extent the experiences of rural youth in agriculture would impact the future of rural entrepreneurship and how they would promote the intention to establish rural business activities. This subject therefore calls for an empirical study to provide key basic data on the factors that influence the intentions of young members of agricultural cooperatives, identify the roles of the experience acquired in collective entrepreneurship, and address information gaps around the intentions of the young members. As well as their capability, their perspectives were sought about self-employment in the future of rural agribusiness. The main objective of this study is to investigate and explain entrepreneurial intention among the rural youth members of agricultural cooperatives as well as identify the vulnerabilities and factors that influence the choice or decision-making between a permanent membership at the cooperative and an entrepreneurial career. In order to serve the main objective, the study sets the following three specific objectives: (i) to identify the determinants of entrepreneurial intention among Moroccan youth in rural areas; (ii) to identify the significance of previous experience and the activities of the cooperative for rural youth in encouraging them to start up a business; and (iii) to distinguish between the activities of the agricultural cooperatives and different perceptions related to entrepreneurial intentions in the determination of the future of rural entrepreneurship. The focus of this paper revolves around problems of entrepreneurial behavior and their impact on the future of agribusiness in rural areas. This paper is organized as thus: following this introduction,

Section 2 sets out the literature review.

Section 3 presents the empirical strategy. Results are presented in

Section 4 and are then discussed and concluded in

Section 5. The paper finishes with brief implications for policy development.

2. Literature Review

The theory of planned behavior (TBP) can be used as the basis for the analysis of entrepreneurial intentions [

12]; in the rural entrepreneurship context the relevant literature has studied the influence exerted by some attitudes on the perceptions to start up agribusinesses [

13]. An attitude has been defined [

26] as the extent to which one perceives entrepreneurial behavior and its significance as beneficial, valuable, and promising. According to [

27], the intentions of youth to engage in entrepreneurship in rural areas are influenced by the attitudinal factors that are identical to individual competency, which refers to the willingness to conduct a certain behavior. A model was developed [

28], which took into account the theory of planned behavior (TPB) for checking how entrepreneurial intention is determined by the personal attitude toward entrepreneurship, by how subjective norms are perceived, and also by behavioral control, which is influenced by demographic factors. Quite a large body of empirical literature is based on the TPB that documents the dimensions for entrepreneurial intentions among the youth, including personal control over behavior and the need for achievement, self-esteem, and innovation [

13,

28], and identifies potential entrepreneurship behavior and its influence on the outcomes of venture creation. The cognitive approach uses cognitive aspects to explain entrepreneurial behavior through cognitions. The field of entrepreneurial cognition includes all aspects of cognition that can potentially play an important role in certain aspects of the entrepreneurial process. Two main lines can be differentiated within the cognitive literature: the study of cognitive structures and the study of cognitive processes. Cognitive structures represent and contain knowledge, while cognitive processes relate to the manner in which that knowledge is received and used. Thus, self-efficacy is the main cognitive aspect reflected in the literature that sheds light on the study of entrepreneurship [

28]. Accordingly, it is crucial to focus on possible factors that might influence the development of self-efficacy. Therefore, we seek to ascertain the impact of the social environment on the self-efficacy beliefs of rural youth members of agricultural cooperatives, with questions on support from family and friends, opportunities, and obstacles to entrepreneurial initiatives in rural areas [

13].

However, in relation to the intention to start up a business, it is the cognitive approach that has awakened the highest interest among the youth [

28]. According to [

29], “entrepreneurial cognitions are the knowledge structures that people use to make assessment, judgment, or decisions involving opportunity evaluation, venture creation and growth”. This cognitive approach in the research field of entrepreneurship emphasizes the importance of perceptions of it rather than the personal qualities of the youth [

28]. These factors are the predictors of how far the young adult is ready to start a business, manage it, and assume the risks of an agribusiness or agri-enterprise. The stronger the social status, attitude towards entrepreneurship, internal market dynamics, and physical infrastructure, the greater the probability of actually starting a business.

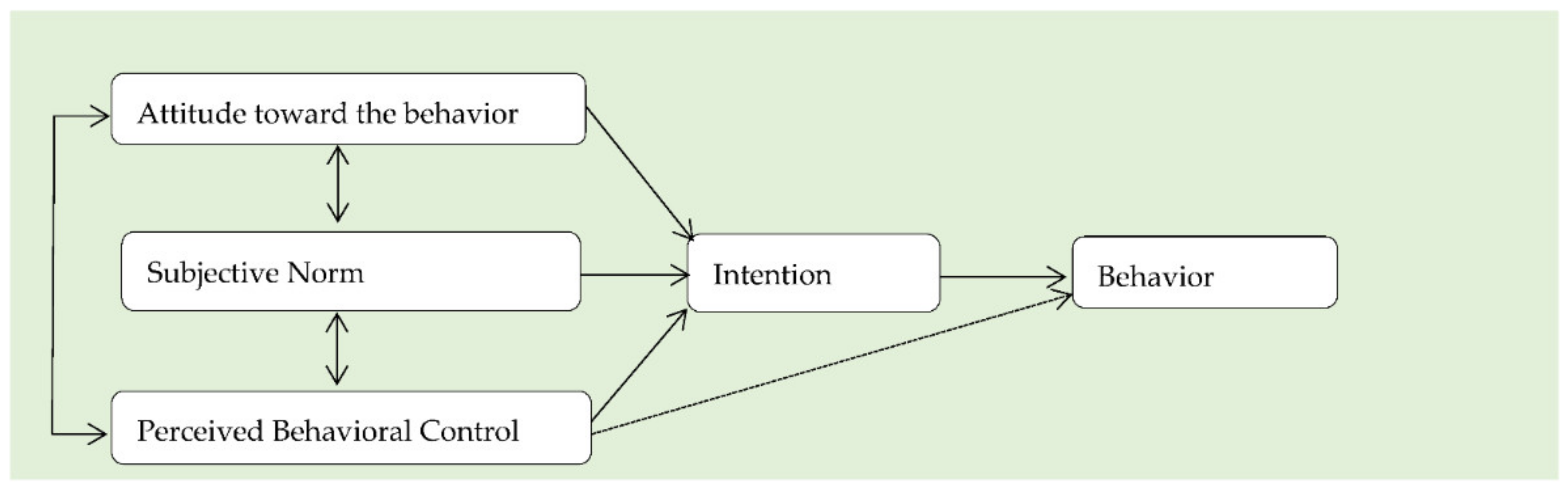

Figure 1 presents the TBP developed by [

29], or the analysis of entrepreneurial intentions. In his model, the intention is assumed as the portrait of a motivation factor that affects action. This indicates that how hard a person tries to formulate behavior for intention is highly correlated with behavior. There are three distinct factors of intention: (i) attitude toward the behavior (refers to how far an individual assesses something as favorable or unfavorable), (ii) subjective norm (experience of a social pressure to do or behave in a certain way), and (iii) perceived behavioral control (a perceived easiness or trouble that is formed from assumptions based on past experience and anticipation of obstacles and barriers).

Several studies in developing countries provide evidence for the applicability of the TPB in the context of youth entrepreneurship. For instance, the authors of [

30] studied entrepreneurial intentions and perceived barriers to entrepreneurship among the youth and found entrepreneurial intentions that focus on the effect of gender from a cross-cultural perspective, including opportunity recognition, creativity, problem solving skills, leadership and communication skills, development of new products and services, and networking skills. Their results confirm that there is an effect of gender and regional culture on the perceived barriers to entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial intentions, particularly on the youth. The authors of [

31] investigated the attitude of African youth towards the creation of new business and entrepreneurship where study results suggest the existence of an active positive attitude among young entrepreneurs that are ready to take risks and stand alone. The authors of [

32] have used [

29] the TPB to investigate the impact of relevant courses on entrepreneurial intentions of students in agriculture. Their results show that the entrepreneurship education program has affected the students’ perceived behavioral control and has had the anticipated positive and negative effects.

According to research that was done [

12], there are several factors that influence young people to become agricultural entrepreneurs. These factors, which are extracted from the literature review, are socio-demography and youths’ skills, vocational experience, attitudes, and educational qualifications. There is, however, a lack of sufficient data regarding entrepreneurial intentions and the incentives offered to young members of agricultural cooperatives. Recent empirical evidence considered that socio-demography was the first factor that affects the attitude of the youth and their acceptance of agricultural entrepreneurship. See [

33,

34]. It includes age, gender, income, youth status, and education level. Demographic factors are the variables that are influencing the youth to take up agricultural entrepreneurship in Indonesia [

12]. Demographic variables that had been studied were gender, age, income, locality, and ethnicity [

12,

32].

Age is one of the most widely studied socio-demographic characteristics. According to [

35], individuals between the ages of 25 and 40 years were more likely than others to start a new business venture because they had obtained sufficient experience in entrepreneurship. This experience is only one example that demonstrates that there are many competencies, such as self-confidence, a positive, professional attitude, and the ability to do business within the rural area. The gender of an individual is another widely studied determinant of entrepreneurship. In recent years, research on both topics experienced rapid expansion and ventured in new directions [

36]. Furthermore, the authors of [

37,

38] suggested that the self-employment sector was traditionally thought to be the domain of the male gender. They explained the reduced entrepreneurial spirit among women through low gender income and education gaps as well as women’s household duties and marital status (see, for example, [

3,

39]).

The importance of education level and training with regard to entrepreneurship intention has been underlined in several pieces of research. According to [

40], education has a major impact on the technical information a young adult has on different career choices, opportunities, and the degree of financial support available. The authors of [

40] draw on social cognitive career theory to examine the relationship between entrepreneurial intention and creating a new venture (i.e., the entrepreneurial career choice). Using unique longitudinal data from almost the entire population of Italian university graduates, entrepreneurial intentions were measured before graduation. Their results show that context plays an important role in explaining why youth do or do not act on their intentions. Relevant others and organizational influences enhance individuals’ likelihood of creating a new venture, whereas environmental influences may inhibit the creation of a new venture [

41]. An important element to consider is that a lower level of education does not provide sufficient opportunity for employment for economically active young adults and therefore contributes to their decisions to start their own businesses [

42].

The remaining studies tested the effect of family circumstances. One of these studies [

43] hypothesized that an increase in family responsibility, widely modeled by the number of children or number of dependents, reduces the probability of an individual choosing self-employment since it increases the cost of business failure. In terms of work experience capturing entrepreneurial behavior and the degree to which entrepreneurship is positively correlated with work experience [

43], an important variable for the intention of the entrepreneur is the motivation from success gained by exploiting an opportunity. In their study, the authors of [

43] explain that the opportunistic entrepreneur is an individual who goes into entrepreneurship as a result of prevailing attractive business opportunities. According to their study, individuals who become opportunistic entrepreneurs consider many factors, which include the economic environment as well as institutional and governmental policies. A number of authors also argue how personal knowledge, past experience, and entrepreneurial skills can help to enhance the process of identifying investment opportunities for young adults [

44,

45].

Several different studies report gender differences in the search for business opportunities. The authors of [

43] claim that men and women differ in some aspects of searching for opportunity. The link with intention experience in the entrepreneurial context may therefore be stronger than in many other contexts. Indeed, daily confrontation with the work of another individual can bring not only well-developed technical knowledge but also a good network that is essential to new ventures and is mainly acquired through practical experience in the business [

43]. In the TPB-inspired model considered here, socio-economic variables and personal attitudes can have a strong influence on entrepreneurial intention, alongside perceived behavioral control. To develop our hypotheses, we bridge different literatures and theoretical perspectives. Specifically, we combine the theory of planned behavior and related existing research on entrepreneurship in rural areas. Based on this our model hypotheses are as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Personal and socio-economic variables will exert a positive effect on entrepreneurial intentions.

Hypothesis 1a (H1a). Socio-demographic variables positively influence entrepreneurial intentions.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b). Individual perceptions positively influence entrepreneurial intentions.

Considering the role of socio-demographic and economic factors on the capacity to generate future business, such as gender, age, education level, and income level of rural youth [

12,

33,

34,

39], there is a strong conceptual and empirical basis that shows the importance of the link between creativity and socio-demographic characteristics [

32]. However, other factors related to public territorial actions and market dynamics play a role as well [

43]. Based on the above argument, our second hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Activities of cooperatives and participation in the agricultural cooperative substantially enhance entrepreneurial intentions among the rural youth.

Hypothesis 2a (H2a). Work experience within agricultural cooperatives positively influences entrepreneurial intentions.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b). The cooperative’s activity sector has an impact on young members with regard to starting a business.

The most successful collective actions are characterized by very strong dynamics and the reflection of a labor market in permanent evolution. In particular, on the one hand, young people in the agricultural cooperatives are assumed to be open to new experiences, and hence their collaborations with each other are expected to be more effective with regard to starting a business [

43]. On the other hand, there is a business opportunity in rural areas, which has a positive impact on entrepreneurial intention of the youth and hence further integrates young people into employment [

7]. Moreover, there is diversity of entrepreneurship (such as necessity- versus opportunity-based) and activities in the rural environment that nurture the generation with new and novel ideas, as well as knowledge, and therefore increases the number of self-employed individuals that will encourage entrepreneurial activity. In other words, those cooperatives in which young people are active in and integrate with provide a stimulating associative activity that connects them in the agricultural sector and rural economy [

46].

This should be particularly true for entrepreneurial activities conducive to private sector development, entrepreneurship, and innovation. The public actions are however insufficient to promote entrepreneurship in rural areas. In fact, fear of failure negatively influences entrepreneurial intention of the youth. This entails assuring concrete measures in the field of entrepreneurship, in particular access to finance, training, and improving business climate [

40,

42,

44]. Therefore, our third hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Factors which characterize the rural environment influence entrepreneurial intention of the youth.

Hypothesis 3a (H3a). Financing constraints negatively influence entrepreneurial intention of the youth and women members of agricultural cooperatives.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b). Fear of failure negatively influences entrepreneurial intention of the youth.

Hypothesis 3c (H3c). Business opportunities in rural areas positively influence entrepreneurial intention of the youth.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

As the introduction to this paper pointed out, research on entrepreneurship intention and African rural youth has experienced some progress over the last few years. However, the actual outcomes of entrepreneurship on rural development are largely unknown. Against this background, the paper’s approach to entrepreneurship intention is very important not only at the individual level but also at the level of associational activity. Specifically, the first important contribution was made by providing classification on the different perceptions related to entrepreneurial intentions. This paper examined the determinants relating to entrepreneurial intentions of rural youth, and classified the factors influencing the choice or decision-making between permanent membership at the cooperative and an entrepreneurial career choice among rural youth. It also identified groups that have been neglected in prior studies and highlighted areas where further research is required. The results have been very promising, but it is necessary to adopt enterprise and encourage job creation in new efficient employment strategies. The findings of this study illustrate that entrepreneurial intention is significantly superior among those of the masculine gender who have no degree. Graduates who opt for such employment opportunities prefer instead to explore employment possibilities in the public sector and foreign countries. The entrepreneurial spirit in young graduates has long been a question of great interest in a wide range of fields. A similar study carried out on entrepreneurship education for graduates indicated that there is a mismatch between education and the type of employment opportunities available in the labor market [

26].

The findings of this study show that gender differences in entrepreneurial intentions had a significant impact on starting a business. The results of this survey indicate that the effect of gender is mediated via social norms that characterize rural environments. The agricultural cooperative is an increasingly important activity in rural areas; it is a collective, solidarity activity where rural women voluntary and joyfully collaborate for the actualization of a socio-economic and community project for income-generating activity. The cooperative aims at providing a supportive environment that rural women can use to maintain family stability and security, but is often not a question of choice but a function of a lack of other options. Young male members of cooperatives with positive entrepreneurial intentions (83.4%) were more likely to have more precise intentions to start a business, vis-à-vis their female counterparts (16.6%). This finding corresponds with the results of a study on gender differences in entrepreneurial intentions [

51]. The effect of gender on entrepreneurial intentions is mediated via personal attitudes and perceived behavioral control but not social norms [

51].

In addition, the age in a group of young adult members of cooperatives is a statistically significant variable that can affect entrepreneurial intentions. As age increases, positive entrepreneurial intentions regularly decrease. Young people aged between 41 and 45 years are attached to their cooperatives, and less likely to start a new business venture than young people between 20 and 25. A similar study also shows that as employees age, they are less inclined to act entrepreneurially, and their entrepreneurial intention is lower the more they identify with their job [

52]. However, these results contradict the results established by the authors of [

52]. These authors assert that the older youth members easily access factors of production, particularly human, social, and financial capital, while younger people may lack experience in running companies, marketing, human resources, sales, sector-specific knowledge regarding customers’ needs, strategic opportunities, and regulatory constraints. Entrepreneurial training, entrepreneurial opportunities, and having experience in cooperatives seem to have a positive impact on the entrepreneurial intentions of young women and men who are members of agricultural cooperatives. A similar study suggests that individuals with an entrepreneurial background were more likely than others to start a new business venture because they had obtained competence, sufficient experience, and self-confidence [

53].

For the barriers facing the youth choosing to embark on entrepreneurship, we have found significant direct relationships with financing constraints, risk perception, and entrepreneurial intention. The survey also shows that the main hindrances to positive entrepreneurial intentions for many youth members of cooperatives result from the lack of access to funding and the complexity of the financial assistance system. However, lack of collateral prevents many young adults from obtaining financial assistance from financial institutions. Similarly, Ref. [

54] noted that, to start a business, a young person needs several sources of funding, including debt financing, government subsidies, and self-financing. Study [

55] also highlighted that, to turn their dream into reality, an individual needs to overcome difficulties in accessing finance. Lack of finance is an obstacle that affects the preferred future career choice of the youth because of financial constraints [

56]. In addition, the dominance of economic uncertainty in rural areas can also negatively influence those that wish to start their businesses. Moreover, young people’s risk of failure in business objectives would increase because adverse and volatile commodity prices, climatic risk, and rural vulnerability affect both entrepreneurship intention and youth engagement in rural economic activities, creating uncertainty in sustainable farm income and the capacity of the youth to develop the entrepreneurial spirit.

There are reasons to believe that entrepreneurial intention in youth cooperatives and the future of rural entrepreneurship are linked. Regarding organizational structure, many of the financing actions for cooperatives are through unallocated equity capital and state subsidies. There have been instances of members being driven less by a wish to involve themselves in the ongoing development of cooperative activities. On the contrary, they are inclined to seek free-riding behavior, as well as avoid investing in the cooperative [

56]. The authors of [

57] evaluated the determinants of students’ preferences of agricultural sub-sector engagement in Cameroon. Their results show that improving the attractiveness of, and working conditions in, the agricultural sector could increase youth engagement in agribusiness and rural economic activities. Thus, the necessity of sustainable entrepreneurship, the detection of effective factors to promote self-employment, and the identification of barriers to entrepreneurship in rural areas will be key sources of security as well as social stability of the country and will also strengthen investment and job creation. How policymakers address these and other challenges to youth engagement in rural economic activities and agribusiness in Morocco will shape the extent to which rural entrepreneurship can play a crucial role in helping young people enter the labor market, reduce poverty, migration, economic disparity, and unemployment, in addition to developing rural areas.

6. Implications for Policy Development

As a result of the dominance of social entrepreneurial ventures and the substantial interest of policymakers to reinforce collective strategy, particularly in rural areas, an increasing number of researchers are focusing on individual entrepreneurs and often characterizing them as major tools for combating youth unemployment. Agricultural cooperatives are among the many manifestations of collective action and represent another form of rural projects for young entrepreneurs in Morocco. Nevertheless, unlike strong collective actions, private initiatives are weak in agribusiness and rural economic activities. Based on the results of this study, the following implications for policy development can be drawn.

Widening and diversifying the sources of funding for rural entrepreneurship: unavailability of finance is one of the biggest constraints that the rural youth are bearing nowadays, especially due to the absence of specific credit for youth businesses and tangible security. We must remove these barriers that prevent young people from engaging in agribusiness and rural economic activities. Further efforts are needed to improve the business environment as well as access to finance. The State must intervene to force banks to develop risky activities and engage them in agriculture and rural development.

Entrepreneurship education: the low level of entrepreneurship education of rural youth and the lack of access to technologies and market information should make us stop and think. These are factors that place rural entrepreneurship at a disadvantage. This has also led to a challenge of lack of technical knowledge, because their awareness of their deficient knowledge makes them less confident in their ability to succeed in starting a business. In doing so, they will need support. A training policy framework aimed at the rural youth based on the real needs of future entrepreneurs should be implemented. Regarding topics to be included in training programs, rural youth have expressed interest in issues such as (I) collaborative leadership for sustainable change; (II) entrepreneurship and innovation; (III) business plans; (IV) a participatory approach and rural development and (V) the provision of targeted, program-specific information, awareness-raising activities, advice, assistance, and training to dismantle administrative barriers to business operation and creation.

Rural women should be encouraged to take up entrepreneurship as a career. Among the challenges facing rural women, traditions and customs which characterize rural society, the family environment, and less access than men to education and training have adverse consequences for their entrepreneurial intentions. This indicates a need to mobilize the Government, all relevant actors, and organizations to reinforce female entrepreneurship to give rural women the place they deserve in rural development, by allowing them to increase their rate of business ownership. Lastly, policymakers must provide constant support of rural women by formulating and implementing a support strategy for transferring knowledge and skills surrounding entrepreneurship in the agri-food sector.

Youth access to land: the youth, with their ability to identify the opportunities offered in rural areas, have been blocked by land tenure. Therefore, access to land, its use, and the enhancement of agriculture are factors contributing to the emergence of the new generation of young entrepreneurs. The State should facilitate their access to land by a profound reform of the land tenure system. This must become a land policy priority in its own right, given the impact of rural depopulation for the future of rural entrepreneurship.

Major implication for academicians: this research provides considerable insight into the entrepreneurial intention among rural youth in agricultural cooperatives; it identified the determinants of entrepreneurial intention among Moroccan youth in rural areas. These findings, presented in this paper, suggest directions in the field of entrepreneurial intention (EI), and provide better information about rural youth members of the cooperatives, their entrepreneurial motivations, and the nature of their issues regarding new venture creation. Furthermore, this research also highlights the major interest of rural entrepreneurship research in in Morocco and other African countries. Though a few researchers have ventured into exploratory studies of different regions (see, for example, [

2,

5,

12,

17,

27]), a lack exists regarding the factors influencing youths’ entrepreneurial intentions. This study could constitute a new research orientation, to stimulate the production of scientific knowledge. In summary, we can definitely state that they are many research areas within the field of rural entrepreneurship which are yet to be explored to the fullest.