The Nexus between Tourism Activities and Environmental Degradation: Romanian Tourists’ Opinions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Impact of Tourism Components on the Environment

2.1.1. Impact of Tourism Transport on the Environment

2.1.2. Impact of Tourist Accommodation Structures on the Environment

2.1.3. Impact of Tourist Recreation on the Environment

2.2. Impact of Tourism Activities on Environmental Degradation

2.2.1. Impact of Tourism Activities on the Loss of Biodiversity

2.2.2. Impact of Tourism Activities on Water Pollution

2.2.3. Impact of Tourism Activities on Air Pollution

2.2.4. Impact of Tourism Activities on Noise Pollution

2.2.5. Impact of Tourism Activities on Waste Increase

2.2.6. Impact of Tourism Activities on Depletion of Natural Resources

3. Research Methodology

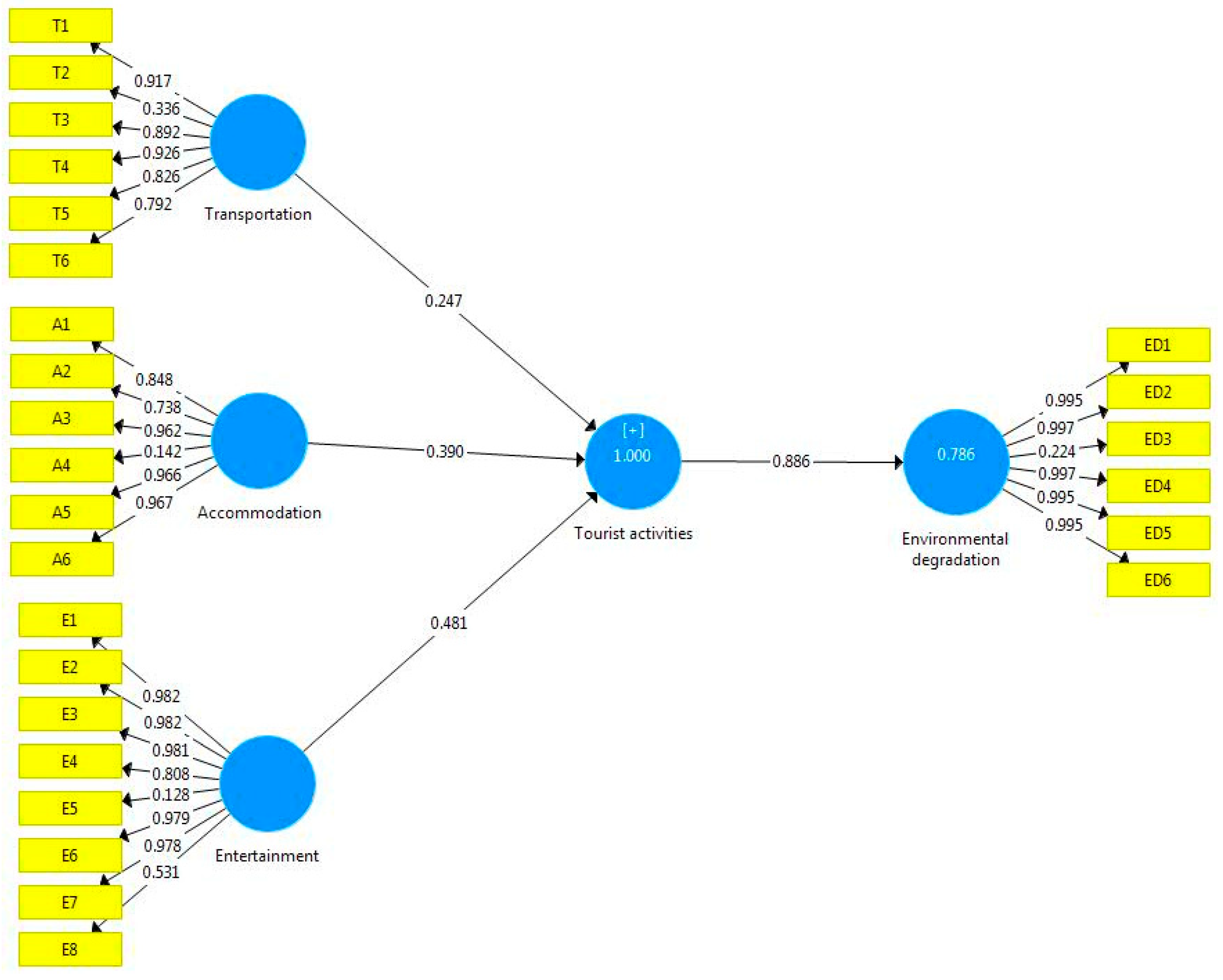

3.1. Theoretical Model

3.2. Data and Sample

3.3. Method

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions, Future Research Directions and Limits

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, Z. An integrated approach to evaluating the coupling coordination between tourism and the environment. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.R. Evaluating the tourism—Environment relationship: Central and East European experiences. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2000, 27, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Tourism and the environment: A geographical perspective. Tour. Geogr. 2000, 2, 337–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, B.; Pérez-Barahona, A.; Strobl, E. Dynamic implications of tourism and environmental quality. J. Public Econ. Theory 2019, 21, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish; Wang, z. Dynamic relationship between tourism, economic growth, and environmental quality. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1928–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, I. The relationships among tourism development, energy demand, and growth factors in developed and developing countries. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 23, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, P.; Chandran, A.; Swain, N. Promoting Gender Sensitivity and Environment Protection through Sustainable Tourism Development: A Review. J. Tour. 2018, 19, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Romeril, M. Tourism and the environment—Towards a symbiotic relationship: (Introductory paper). Int. J. Environ. Stud. 1985, 25, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdell, C. Globalisation and sustainability: Environmental Kuznets curve and the WTO. Ecol. Econ. 2001, 39, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Maquieira, J.; Lozano, J.; Gomez, C.M. Quality standards versus taxation in a dynamic environmental model of a tourism economy. Environ. Model. Softw. 2009, 24, 1483–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Netto, A.P. What is tourism? Definitions, theoretical phases and principles. Philos. Issues Tour. 2009, 37, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, Y.; Dissart, J.C. Natural and environmental amenities: A review of definitions, measures and issues. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 146, 475–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cracolici, M.F.; Nijkamp, P. The attractiveness and competitiveness of tourist destinations: A study of Southern Italian regions. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vengesayi, S.; Mavondo, F.T.; Reisinger, Y. Tourism destination attractiveness: Attractions, facilities, and people as predictors. Tour. Anal. 2009, 14, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapkus, R.; Dapkute, K. Evaluation of the Regional Tourism Attractiveness. Res. Rural Dev. 2015, 2, 293–300. Available online: https://llufb.llu.lv/conference/Research-for-Rural-Development/2015/LatviaResearchRuralDevel21st_volume2-293-300.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Green, H.; Hunter, C. The environmental impact assessment of tourism development. Perspect. Tour. Policy 1992, 29–47. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19921896476 (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Sghaier, A.; Guizani, A.; Jabeur, S.B.; Nurunnabi, M. Tourism development, energy consumption and environmental quality in Tunisia, Egypt and Morocco: A trivariate analysis. GeoJournal 2019, 84, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, M.; Hassan, S.; Azam, M.; Suryanto, T. The dynamics of governance, tourism and environmental degradation: The world evidence. Int. J. Glob. Environ. Issues 2018, 17, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Tourism and biodiversity: More significant than climate change? J. Herit. Tour. 2010, 5, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baoying, N.; Yuanqing, H. Tourism development and water pollution: Case study in Lijiang Ancient Town. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2007, 17, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, A.; Godil, D.I.; Xu, B.; Sinha, A.; Khan, S.A.R.; Jermsittiparsert, K. Revisiting the role of tourism and globalization in environmental degradation in China: Fresh insights from the quantile ARDL approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 122906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulistan, A.; Tariq, Y.B.; Bashir, M.F. Dynamic relationship among economic growth, energy, trade openness, tourism, and environmental degradation: Fresh global evidence. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 13477–13487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gedik, S.; Mugan-Ertugral, S. The effects of marine tourism on water pollution. Fresenius Environ. Bull 2019, 28, 863–866. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20193484954 (accessed on 7 March 2021).

- Gössling, S.; Peeters, P.; Hall, C.M.; Ceron, J.P.; Dubois, G.; Scott, D. Tourism and water use: Supply, demand, and security. An international review. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuvan, Y. Mass tourism development and deforestation in Turkey. Anatolia 2010, 21, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.E.; Song, K.; Kim, M.; Lee, J. Transformation planning for resilient wildlife habitats in ecotourism systems. Sustainability 2017, 9, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolich, K.; Halliday, W.D.; Pine, M.K.; Cox, K.; Black, M.; Morris, C.; Juanes, F. The sources and prevalence of anthropogenic noise in Rockfish Conservation Areas with implications for marine reserve planning. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 164, 112017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Gao, J. Exploring the effects of international tourism on China’s economic growth, energy consumption and environmental pollution: Evidence from a regional panel analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katircioglu, S.T. International tourism, energy consumption, and environmental pollution: The case of Turkey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 36, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés-Ordóñez, O.; Castillo-Olaya, V.A.; Granados-Briceño, A.F.; García, L.M.B.; Díaz, L.F.E. Marine litter and microplastic pollution on mangrove soils of the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta, Colombian Caribbean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 145, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anup, K.C. Tourism and its role in environmental conservation. J. Tour. Hosp. Educ. 2018, 8, 30–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rastegar, R. Tourism development and conservation, do local resident attitudes matter? Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2019, 19, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Jorge, S.; Gomes, I.; Hayes, K.; Corti, G.; Louzao, M.; Genovart, M.; Oro, D. Effects of nature-based tourism and environmental drivers on the demography of a small dolphin population. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 197, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, G.D.; Dabezies, J.M. Tourism development and environmental conservation: Tensions in the protected landscape of Lunarejo Valley, Uruguay. ROSA DOS VENTOS-Tur. E Hosp. 2019, 11, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walpole, M.; Goodwin, H. Local attitudes towards conservation and tourism around Komodo National Park, Indonesia. Environ. Conserv. 2001, 28, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.O.; Zhang, R.Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.R.; Wei, Z.C. Residents’ environmental conservation behaviour in the mountain tourism destinations in China: Case studies of Jiuzhaigou and Mount Qingcheng. J. Mt. Sci. 2017, 14, 2555–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukashina, N.S.; Amirkhanov, M.M.; Anisimov, V.I.; Trunev, A. Tourism and environmental degradation in Sochi, Russia. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetto, G.; Soriani, S. Tourism and environmental degradation: The Northern Adriatic Sea. Sustain. Tour. Eur. Exp. 1996, 137–152. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19961807091 (accessed on 25 April 2021).

- Ahmad, F.; Draz, M.U.; Su, L.; Rauf, A. Taking the bad with the good: The nexus between tourism and environmental degradation in the lower middle-income Southeast Asian economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 1240–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.; Alam, M.M.; Hafeez, M.H. Effect of tourism on environmental pollution: Further evidence from Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 190, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Draz, M.U.; Su, L.; Ozturk, I.; Rauf, A. Tourism and Environmental Pollution: Evidence from the One Belt One Road Provinces of Western China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.A.; Sharif, A.; Wong, W.K.; Karim, M.Z.A. Tourism development and environmental degradation in the United States: Evidence from wavelet-based analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1768–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, F.; Galati, O.I.; Nocera, S. Climate change impacts and tourism mobility: A destination-based approach for costal areas. Int. J. Sustain. Destin. 2020, 15, 456–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasojevic, B.; Lohmann, G.; Scott, N. Air transport and tourism—A systematic literature review (2000–2014). Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 975–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, S.; Rasheed, I.M.; Pitafi, A.H.; Pitafi, A.; Ren, M. Road and Transport infrastructure development and community support for tourism: The role of perceived benefits, and community satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, E.; Ulucak, R.; Ulucak, Z.S. The impact of tourism development on CO2 emissions: An advanced panel data estimation. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neger, C.; Prettenthaler, F.; Gössling, S.; Damm, S. Carbon intensity of tourism in Austria: Estimates and policy implication. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 33, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, A.; Martinez-Blanco, J.; Mont Meó, M.; Rodriguez, G.; Tavares, N.; Arias, A.; Oliver-Solà, J. Carbon footprint of tourism in Barcelona. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamb, A.; Lundberg, E.; Larsson, J.; Nilsson, J. Potentials for reducing climate impact from tourism transport behaviour. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1365–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Driha, O.M.; Bekun, F.V.; Adedoyin, F.F. The Asymetric impact of air transport on economic growth in Spain: Fresh evidence from tourism-led growth hypothesis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyuboglu, K.; Uzar, U. The impact of tourism on CO2, emission in Turkey. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 23, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehigiamusoe, K.U. Tourism, growth and environment: Analysis of non-linear and moderating effects. J. Sustain. 2020, 28, 1174–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetanah, B.; Fouzel, S. Investigating the impact of climate change on the tourism sector: Evidence from a sample of island economies. Tour. Rev. 2018, 74, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, L.; Ison, S. Responsible transport: A post-COVID agenda for transport policy and practice. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 6, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šebešová, A.; Kršák, B. Notes on the impact of cycling infrastructure on tourist destination management. Acta Geoturistica 2018, 9, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieckowski, M. Will the consequences of COVID-19 trigger a redefining of the role of transport in the development of sustainable tourism? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voon, B.H.; Hamali, J.; Jussem, P.M.; Teo, A.K.; Kanyan, A. Socio-Environmental Dimensions of Tourism Service Experience in Homestays. Int. J. Geomate 2017, 12, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pobihun, O.; Korobeinykova, Y.; Nykodiuk, O.; Melnyk, A. Mechanisms for Ensuring the Environmental Safety of Tourist Destinations. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Sustainable Futures: Environmental, Technological, Social and Economic Matters (ICSF 2021), Kryvyi Rih, Ukraine, 12–21 May 2021; Volume 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantakou, E.; Terkenli, T.S. Non-Institutionalized Forms of Tourism Accommodation and Overtourism Impacts on the Landscape: The Case of Santorini, Greece. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Lund-Durlacher, D. Tourist accommodation, climate change and mitigation: An assessment for Austria. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegaki, A.N.; Agiomirgianakis, G.M. Sustainable Technologies in Greek Tourist Accommodation: A Quantitative Review. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2018, 21, 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moreno-Luna, L.; Robina-Ramírez, R.; Sánchez, M.S.-O.; Castro-Serrano, J. Tourism and Sustainability in Times of COVID-19: The Case of Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urh, B. The Impact of leisure and tourism on public health in pandemic times. Quaestus 2021, 18, 84–95. Available online: https://www.quaestus.ro/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Barbara-Uhr2.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Naidoo, R.; Burton, A.C. Relative effects of recreational activities on a temperate terrestrial wildlife assemblage. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2020, 2, e271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumanapala, D.; Wolf, I.D. Recreational Ecology: A Review of Research and Gap Analysis. Environments 2019, 6, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddy, J.K.; Webb, N.L. The influence of the environment on adventure tourism: From motivations to experiences. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 21, 2132–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeharry, Y.; Bekaroo, G.; Bussoopun, D.; Bokhoree, C.; Phillips, M.R. Perspectives of leisure operators and tourists on the environmental impacts of coastal tourism activities: A case study Mauritius. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 10702–10726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeill, T.; Wozniak, D. The economic, social, and environmental impacts of cruise tourism. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, D. The collapse of tourism and its impact on wildlife tourism destinations. J. Tour. Futures 2020. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JTF-04-2020-0053/full/html (accessed on 14 August 2021). [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Mubeen, R.; Iorember, P.T.; Raza, S. Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on tourism: Transformational potential and implications for a sustainable recovery of the travel and leisure industry. Curr. Res. Behav. Sci. 2021, 2, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, P.; Rotmans, J.; de Groot, D. Biodiversity: Luxury or necessity? Glob. Environ. Chang. 2003, 13, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibullah, M.S.; Din, B.; Chong, C.W.; Radam, A. Tourism and biodiversity loss: Implications for business sustainability. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 35, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Walsh, D. Review of studies on environmental impacts of recreation and tourism in Australia. J. Environ. Manag. 1998, 53, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C.M.; Hill, W. Impacts of recreation and tourism on plant biodiversity and vegetation in protected areas in Australia. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 85, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Ding, Z.; Yang, X. Review of oversea studies on tourism impact of water environment. Prog. Geogr. 2005, 1, 127–136. Available online: https://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-DLKJ200501014.htm (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Carić, H.; Mackelworth, P. Cruise tourism environmental impacts–The perspective from the Adriatic Sea. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 102, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, N. The impact of cruise ship generated waste on home ports and ports of call: A study of Southampton. Mar. Policy 2007, 31, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.A. Responsible cruise tourism: Issues of cruise tourism and sustainability. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2011, 18, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, B.H. A State of the Environment Report: Pollutants in British Columbia’s Marine Environment: A status report. Ott. Environ. Can. 1989, 89, 1–62. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2020/eccc/En1-11-89-1-eng.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2021).

- Walter, S. Climate change and the skiing industry: Impacts and potential responses. Res. Semin. Arct. Stud. Program. 2001. Available online: http://kaares.ulapland.fi/home/hkunta/jmoore/climateskiing.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2017).

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Relvas, H.; Gama, C.; Lopes, M.; Borrego, C.; Rodrigues, V.; Robaina, M.; Madaleno, M.; Carneiro, M.; Eusébio, C.; et al. Estimating emissions from tourism activities. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 220, 117048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.C.; Wang, C.S. Tourism, the environment, and energy policies. Tour. Econ. 2018, 24, 821–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leduc, A.O.; Nunes, J.A.C.; de Araújo, C.B.; Quadros, A.L.; Barros, F.; Oliveira, H.H.; Simões, C.R.M.; Winandy, G.S.; Slabbekoorn, H. Land-based noise pollution impairs reef fish behavior: A case study with a Brazilian carnival. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 253, 108910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, S.V.; Ölçer, A.I.; Ballini, F. The development of a policy framework to mitigate underwater noise pollution from commercial vessels: The role of ports. Mar. Policy 2020, 120, 104132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrier-Pagès, C.; Leal, M.C.; Calado, R.; Schmid, D.W.; Bertucci, F.; Lecchini, D.; Allemand, D. Noise pollution on coral reefs?—A yet underestimated threat to coral reef communities. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 165, 112129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napper, I.E.; Davies, B.F.; Clifford, H.; Elvin, S.; Koldewey, H.J.; Mayewski, P.A.; Miner, K.R.; Potocki, M.; Elmore, A.C.; Gajurel, A.P.; et al. Reaching new heights in plastic pollution—Preliminary findings of microplastics on Mount Everest. One Earth 2020, 3, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiano, A.; Crovella, T.; Lagioia, G. Managing sustainable practices in cruise tourism: The assessment of carbon footprint and waste of water and beverage packaging. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.C.; Wang, Y.; Zuo, J. The nexus of water-energy-food in China’s tourism industry. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH Boenningstedt 2015. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 1–12. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2233795 (accessed on 3 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Ali, Faizan, Kim, Woo Gon, Ryu, Kisang, The effect of physical environment on passenger delight and satisfaction: Moderating effect of national identity. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 213–224. [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Structural equation modelling and regression analysis in tourism research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 15, 777–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H.; Gursoy, D. Use of Structural Equation Modeling in Tourism Research: Past, Present, and Future. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.W.; Stewart, W.P. A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eusébio, C.; Carneiro, M.J.; Caldeira, A. A structural equation model of tourism activities, social interaction and the impact of tourism on youth tourists’ QOL. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2016, 6, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afthanorhan, A.; Awang, Z.; Fazella, S. Perception of Tourism Impact and Support Tourism Development in Terengganu, Malaysia. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.C.C.; Gursoy, D.; Del Chiappa, G. The Influence of Materialism on Ecotourism Attitudes and Behaviors. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gültekin, Y.S.; Gültekin, P.; Uzun, O.; Gök, H. Use of Structural Equation Modeling in Ecotourism: A Model Proposal. Period. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2017, 5, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campdesuñer, R.P.; García Vidal, G.; Sánchez Rodríguez, A.; Martínez Vivar, R. Structural equation model: Influence on tourist satisfaction with destination atributes. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 23, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitip, P.; Chaiboonsri, C.; Kovács, S.; Balogh, P. A Structural Equation Model: Greece’s Tourism Demand for Tourist Destination. Appl. Stud. Agribus. Commer. 2010, 4, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.K. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) Using LISREL. Available online: http://www.masil.org/documents/SEM.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarsted, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; Available online: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/facbooks2014/39/ (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Lohmoller, J.B. Latent Variable Path Modelling with Partial Least Squares; Physica-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, C.; Becken, S.; Nguyen, K.; Stewart, R.A. Transitioning to smart sustainable tourist accommodation: Service innovation results. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 201, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.L.; Tsung, H.L. How do recreation experiences affect visitors’ environmentally responsible behavior? Evidence from recreationists visiting ancient trails in Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 705–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Peeters, P. Assessing tourism’s global environmental impact 1900–2050. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.S.; Hsieh, T. An environmental performance assessment of the hotel industry using an ecological footprint. J. Hosp. Manag. Tour. 2011, 2, 1–11. Available online: https://academicjournals.org/article/article1379503548_Chen%20and%20Hsieh%20pdf.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Lee, C.C.; Chen, M.P. Ecological footprint, tourism development, and country risk: International evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, I.; Al-Mulali, U.; Saboori, B. Investigating the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis: The role of tourism and ecological footprint. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 1916–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tourists’ Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–25 years | 51(25.1%) |

| 25–35 years | 61(30.0%) |

| 35–45 years | 64 (31.5%) |

| 45–55 years | 21 (10.3%) |

| 55–65 years | 6 (3.0%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 97 (47.8%) |

| Female | 106 (52.2%) |

| Education | |

| High school | 84 (41.4%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 91 (44.8%) |

| Master’s degree | 28 (13.8%) |

| Transport | |

| T1 | In your tourist travels, the train is the most often used means of transport. |

| T2 | In your tourist travels, the car is the most often used means of transport. |

| T3 | In your tourist travels, the plane is the most often used means of transport. |

| T4 | You are willing to replace a means of transport (plane, car) with a less polluting one (train) in your tourist travels to protect the environment. |

| T5 | Choosing the least polluting/the most environmentally friendly means of transport when traveling is an important concern for you. |

| T6 | You are willing to use at the destination the local public transport or the bicycle to reduce the carbon footprint. |

| Accommodation | |

| A1 | If an ecological guide were offered at the destination, you would change your behaviour, paying more attention to your tourist activities and to their impact on the environment. |

| A2 | You are willing to pay an ecological tax at your destination to minimise the environmental footprint |

| A3 | You pay special attention to the selective collection of waste at your accommodation. |

| A4 | You pay special attention to water consumption at your accommodation, making efforts not to waste water. |

| A5 | You pay special attention to energy consumption at your accommodation, making efforts to save energy. |

| A6 | You request a change of towels and linen only at the end of your stay. |

| Entertainment | |

| E1 | In the tourist activities you perform in nature you are very careful not to destroy the plants. |

| E2 | In the tourist activities you perform in nature you are very careful not to disturb the animals. |

| E3 | In the tourist activities you perform in nature you are very careful not to make noise. |

| E4 | In the tourist activities you perform in nature you are very careful not to leave waste. |

| E5 | In the tourist activities you perform in nature you are very careful to eliminate the waste in special places for this purpose. |

| E6 | In the tourist activities you perform in nature you are very careful to light a fire only in special places for this purpose. |

| E7 | In the tourist activities you perform in nature you prefer to ride a bicycle or to go on foot. |

| E8 | In the tourist activities you perform in nature you are careful to preserve the areas protected by law. |

| Environmental degradation | |

| ED1 | Your tourist activities (regarding transport, accommodation or entertainment) affect the environment, contributing to the destruction of biodiversity. |

| ED2 | Your tourist activities (regarding transport, accommodation or entertainment) affect the environment, contributing to water pollution. |

| ED3 | Your tourist activities (regarding transport, accommodation or entertainment) affect the environment, contributing to air pollution. |

| ED4 | Your tourist activities (regarding transport, accommodation or entertainment) affect the environment, contributing to noise pollution. |

| ED5 | Your tourist activities (regarding transport, accommodation or entertainment) affect the environment, contributing to waste increase. |

| ED6 | Your tourist activities (regarding transport, accommodation or entertainment) affect the environment, contributing to the depletion of natural resources (by water, energy, fuel consumption—or other resources). |

| Responses (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| ED1—The tourist activities you perform in the environment lead to biodiversity loss. | 8.00 | 13.60 |

| ED2—The tourist activities you perform in the environment lead to water pollution. | 20.90 | 11.90 |

| ED3—The tourist activities you perform in the environment lead to air pollution. | 20.20 | 18.60 |

| ED4—The tourist activities you perform in the environment lead to noise pollution. | 9.80 | 11.90 |

| ED5—The tourist activities you perform in the environment lead to waste increase. | 28.80 | 28.80 |

| ED6—The tourist activities you perform in the environment lead to depletion of natural resources. | 12.30 | 15.30 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Construct (The Model of Environmental Degradation) | Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transportation | 0.882 | 0.927 | 0.913 | 0.653 |

| Accommodation | 0.875 | 0.962 | 0.917 | 0.679 |

| Entertainment | 0.922 | 0.972 | 0.948 | 0.720 |

| Tourist activities | 0.942 | 0.972 | 0.953 | 0.538 |

| Environmental degradation | 0.942 | 0.999 | 0.965 | 0.835 |

| Relationships | Path Coefficient | T Statistics | Is the Hypothesis Supported? |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 Transportation ->Tourist activities | 0.247 * | 1.766 | YES |

| H2 Accommodation ->Tourist activities | 0.390 ** | 2.447 | YES |

| H3 Entertainment ->Tourist activities | 0.481 *** | 4.763 | YES |

| H4 Tourist activities ->Environmental degradation | 0.886 ** | 2.018 | YES |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ștefănică, M.; Sandu, C.B.; Butnaru, G.I.; Haller, A.-P. The Nexus between Tourism Activities and Environmental Degradation: Romanian Tourists’ Opinions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169210

Ștefănică M, Sandu CB, Butnaru GI, Haller A-P. The Nexus between Tourism Activities and Environmental Degradation: Romanian Tourists’ Opinions. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):9210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169210

Chicago/Turabian StyleȘtefănică, Mirela, Christiana Brigitte Sandu, Gina Ionela Butnaru, and Alina-Petronela Haller. 2021. "The Nexus between Tourism Activities and Environmental Degradation: Romanian Tourists’ Opinions" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 9210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169210

APA StyleȘtefănică, M., Sandu, C. B., Butnaru, G. I., & Haller, A.-P. (2021). The Nexus between Tourism Activities and Environmental Degradation: Romanian Tourists’ Opinions. Sustainability, 13(16), 9210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169210