1. Introduction

The volumes of investors’ funds funneling into sustainable investments rise every year with no decline being insight. In 2020, more than 51 billion USD of new funds were channeled into sustainably acting companies, more than double the amount in 2019 [

1]. Consequently, the demand for data for non-financial due diligence is not lagging. The most widely spread approach in performing the ESG evaluation leans on the independent rating agencies. By assessing and diligently evaluating the indicators relating to environmental impact, social endeavors, and corporate governance, the ESG rating agencies plug the data into their methodologies and evaluation models. The results usually come out in a single score or a rating [

2].

As sustainability-related data are often qualitative and arguably challenging to compare, the outcomes tend to differ. Eccles et al. (2019) say that there are around 500 ESG rankings, more than 100 ESG awards, and 120 voluntary ESG disclosure standards estimated to have been in the market as of 2019 [

3]. The lack of commonly unified standards for ESG measurement has led to considerable differences in how ESG is measured and evaluated by different data vendors. Consequently, when Berg et al. (2019) compared the sustainability ratings by five market-leading ESG rating agencies, authors found an average correlation coefficient of 0.61, far from a perfect correlation of 0.99 exhibited, for example, among the credit ratings [

4]. While the academic literature provides some explanation for these differences e.g., due to data quality and collection methods, the differences in scoring models and methodologies remain. In addition, as investors pay for the ESG scores, in contrast to the situation in credit scoring, where the companies compensate for their scores, the puzzle of variances in the ESG ratings is far from being resolved.

An additional challenge comes from the fact that, due to the data availability and the fast pace of the market growth, the market penetration of the ESG scoring is still relatively low when measured by the number of companies scored. According to OECD, the rate of the ESG rating availability is significantly higher when measured by the market capitalization implying that there is a trend in the favor of the larger market capitalization companies to be awarded an ESG score and thus further deviating the investment interest away from the smaller peers with fewer resources to devote to sustainability implementation and reporting [

5].

The present study aims to analyze the ESG rating availability and its divergence for the companies listed on the stock exchanges of Europe. Firstly, it contributes to the ESG rating-related literature by comparing various ESG scores awarded to European stock-listed companies, which arguably should have similar legislative obligations for non-financial data disclosure, thus encouraging a higher degree of comparability. Based on the external ESG scores available on the Bloomberg platform (including some of the most widely used such as Sustainalytics, RobecoSAM, MSCI as well as the Bloomberg disclosure score, and ISS Quality score), the correlations between the scores of different providers are calculated and compared. In the first part of the research, therefore, the differences across industries are analyzed by using the mean average distance to the average rating of each entity to observe any patterns in convergence or deviations between the scores.

Secondly, this paper explores the ESG rating availability for the Central and Eastern European (CEE) companies to test whether higher liquidity is observed for those stocks that have an external ESG score. Independent

t-test analysis between the sample of companies having the ranking and a sample of unranked companies is performed in the second part of the research to explore the underlying differences. The justification for choosing CEE companies as the analytical sample is the intent to focus on the emerging region in Europe, where ESG factors so far have been of a lower priority compared to Western Europe and Scandinavian countries. Based on the authors’ best knowledge, comparable academic research relevant for the specificity of the emerging financial markets in Europe is currently lacking. According to research, the investors in the region are already actively using ESG analysis in their investment decisions, thus implying the future trend of an increase in the demand for external ESG assessments necessary for investment evaluation [

6,

7].

In the current financial market, which is strongly led by sustainability trends, this study contributes to the academic literature by providing an analysis of the external ESG score availability and differences for the European companies. It also provides input for the investors, which are using external rankings to decide on their investments as well as informs the companies and policymakers about the importance and implied liquidity benefits of having external sustainability scores. Finally, it contributes novel evidence to the CEE region specific academic literature, which helps to explain the differences that exist between the companies and financial market of the Western Europe and the CEE region.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of the ESG Ratings

An increasing number of companies are being appraised by sustainability rating agencies with an aim to provide relevant data for stakeholders, which would like to use the non-financial information on the companies to evaluate their investments or construct portfolios [

8]. A recent market study of 2020 expects at least 20% annual growth for the ESG data business [

9]. Arguably, the ultimate users of the ESG ratings are the investors, which employ ESG ratings as an objective source of data ensuring that their funds flow into companies with a decent corporate social performance as increasingly demanded by their limited partners [

10].

Li & Polychronopoulos (2020) has offered a typology of the most common approaches of the ESG data and rating providers differentiating between (1)—companies like Refinitiv and Bloomberg collecting data from public sources, but not offering any value-adding input or scoring, (2) comprehensive—including ESG data providers that gather public and own-created data to combine it via own methodology to issue a score or a rating (e.g., Sustainalytics, MSCI, RepRisk), (3) specialists—companies focusing on specific ESG issue (e.g., Carbon Disclosure Project). The classification and differences among them strongly highlight that the focus and the methodological approach of the providers is of utmost importance. While some rating agencies evaluate the company endeavors based on compliance to certain sustainability standards, others put more weight on the company’s ability to recognize and manage the risks [

11]. Additional differences emerge based on the consideration of the materiality in the whole assessment process [

12]. Finally, the data sources used and the exact metrics applied cause an additional gap, where the differences in the outcome can emerge [

13].

While there are estimated to be over 500 ESG rankings available, the large share of investors and interested parties still rely on the most impactful players [

3]. An overview of the arguably most prominent and frequently used ESG data and rating providers is compiled in the following section. It offers to obtain at least a glimpse of the differences of the scoring approaches likely to explain some of the further documented divergences.

2.1.1. MSCI ESG Ratings

MSCI has more than 17 years of industry expertise. It covers around 14 thousand issuers linked to 600 thousand securities. MSCI ESG rating provides an overall ESG score on a seven-grade scale from AAA to CCC. The legacy companies of MSCI include KLD, Innovest, IRRC, and GMI Ratings [

14]. The data is analyzed against 35 ESG issues, measuring the extent the company is exposed to the risks of specific industries and how well the company is managing those risks. Additionally, a relative comparison to the company’s peers is provided. The key issues are particular to each industry and can be updated annually. The E and S sub-scores are derived by calculating a weighted average of individual material issue scores relative to the corresponding industry peer group. The weights are set individually for each GICS Sub-industry ranging from 5–30%. The risk exposure and ability to manage the risk are combined in the assessment. The governance score, contrary, is awarded on absolute terms on a scale from 0 to 10 and includes metrics regarding ownership, pay, board, accounting, business ethics, and tax. ESG Controversy score, measured from 0 to 10, provides an assessment of controversies having a potentially negative effect on the company’s operations coming from factors as measured by ESG [

15].

The data sources comprise macro data from academic and governmental data sets, the company level disclosures like annual and sustainability reports and daily monitored media news. Systemic communication with companies is performed to verify the data [

14].

2.1.2. RobecoSAM

RobecoSAM has been active in the sustainable investment market for over 25 years. In 2019 the ESG data business of this company was acquired by S&P Global [

16]. The data source of RobecoSAM ratings is the Corporate Sustainability Assessment (CSA) survey—an annual questionnaire filled by large companies globally. The CSA, which S&P acquired in line with RobecoSAM, has been in the market since 1999 and allows companies to report their sustainability performance. In 2021, the list of CSA invited companies comprised 5000 global corporations [

17].

Its most recent ESG rating score (named the Smart ESG score) aims to account for previously in the academic literature mentioned biases arising due to differences in geography, company size, and disclosure level. The adjustments are made on different levels. Firstly, as ESG disclosures are more developed in Europe, the scores that award points for data availability usually result in higher scores awarded for European companies. Similarly, larger companies, which typically have extra resources to develop more sophisticated sustainability policies, usually end up scoring higher in the ESG scores than their peers. RobecoSAM Smart ESG scores adjust to these differences by comparing only those companies with similar sectoral and geographical backgrounds. In addition, heavier weights are provided for issues having a financially material impact on specific industries. The final result is assessed on a 100 point scale [

18].

2.1.3. Sustainalytics

Sustainalytics has been in the ESG market for around 25 years and, as of 2021, provides sustainability-related ratings to more than 20 thousand companies worldwide. In 2020 the company was acquired by Morningstar Inc. [

19]. The methodology of Sustainalytics combines a quantitative score representing the part of the ESG risks that remains unmanaged (measured in an open-end scale) and a risk category, which is assessed based on the quantitative score peer comparison. The ESG score (expressed on a 100-point scale) is calculated based on three pillars– corporate governance, material ESG issues, and idiosyncratic issues measured on the company level. The dimensions are evaluated from two viewpoints—exposure to the specific ESG factor and the company’s ability to manage this risk. To tailor the industry-wide scoring to a specific company, the company’s ESG exposure to the particular issue is derived via beta estimation over the quantitative factors like production, financials, events, and geographical location, as well as individual qualitative assessment.

The data sources used in the industry scoring process include quantitative mark gained from numeric data, corporate standpoint obtained via company’s disclosures, and expert opinion represented by industry expertise of the scorers. The industry scores are updated annually. The specific company data is also updated annually based on publicly disclosed information. The rating agency obtains the company’s feedback before the final score is assessed [

20].

2.1.4. ISS Quality Score

The ISS quality score does not offer a complete sustainability assessment. Instead, it focuses only on the governance aspects. The score has been awarded to more than 6000 companies globally. The methodology of the governance score is numeric and assesses the governance risks of the individual company relative to its peers and the region.

ISS Quality score assesses four dimensions—board structure, compensation practices, shareholder rights, and audit and risk management. The dimensions altogether encompass more than 220 single factors. After weight-based analysis of the individual dimensions, the Governance Quality Score is ultimately expressed on a scale from 1 to 10, where a lower score corresponds to a lower risk level [

21].

2.1.5. RepRisk

RepRisk does not provide an ESG rating but instead offers a view on those ESG risks that will be material in data sets. Contrary to other similar service providers, RepRisk excludes the company’s self-reported information arguing that it cannot be trusted, and therefore only external, public data is sourced in the analysis.

Machine learning tools are used for information gathering, ensuring daily screening of more than half a million documents in 20 languages. The key output is expressed in the form of the RepRisk Index—a quantitative measure on a scale from 0 to 100 concerning the reputational risk exposure to ESG issues, and RepRisk Rating—measured on a scale from AAA to D to ease the benchmarking and comparison [

22].

Some of the other widely used and impactful rating agencies include Corporate Knights Global 100 publishing an annual index of the most sustainable companies, Thomson Reuters ESG Research Data (including legacy company Asset4), which measures the ESG performance and Controversy score, based on public data as well Bloomberg ESG data service, which published an ESG disclosure score (2).

2.2. Sources of Divergence in ESG Ratings

Sustainability data availability and quality are among the most considerable problems, currently seen as an obstacle to a more extensive application of sustainable investments [

23]. The academic literature has recognized that data inconsistency creates challenges in proper data evaluation. Kotsantonis & Serafeim (2019) in their analysis, reviewed a sample of 50 large publicly listed companies and manually collected their disclosures on employee health and safety data. The authors found more than 20 different ways the sample companies chose to report this metric, implying that such inconsistencies lead to significantly different ESG score results [

24]. Other authors highlight the ESG data quality problem, suggesting a trade-off between validity and reliability of ESG data [

25].

Firm-specific effects can potentially cause additional differences. Drempetic et al., (2020) used Thomson Reuters ASSET4 ESG ratings to analyze the impact of firm size, available resources for ESG data compilation, and obtainability of the ESG data on the company’s score. The authors documented a significant positive correlation concluding that a bias towards less resourceful companies can emerge across the ratings [

26]. According to a recent comparison between Thomson Reuters, RobecoSAM, and Sustainalytics scores, there was a tendency by all three rating agencies to award higher average scores to larger companies [

12]. Similar ESG rating influencing factors relate to the regional differences as, e.g., European companies tend to disclose a more comprehensive set of non-financial results than non-European firms [

27]. Some of the ratings, such as the RobecoSAM ESG score, claim to already account for these potential biases [

18].

As to why the differences emerge, Eccles & Stroehle (2018) suggested that the social origins of the ESG rating agencies play an important role in the set-up of their ESG measurements [

28]. Exploring further Eccles et al. (2019) used in-depth literature and document analysis as well as interviews to tackle the differences among two ESG data vendors—KLD and Innovest. Authors found that differences in company history and initial purpose created Innovest’s ratings to be more financial-value driven, while KLD’s implied belief in the meaning of sustainable development and higher value-added resolution led their ratings to be more value-driven [

3].

All of the aforementioned aspects largely impact the set-up of the scoring process. Consequently, the ESG ratings tend to showcase a significant divergence. The divergence is confirmed by academic literature—Chatterji et al. (2016) examined six ESG rating agencies (KLD, Asset4, Calvert, FTSE4good, DJSI, and Innovest) and generally found a lack of consensus among the issued ratings [

29]. Furthermore, the differences remained even after adjusting for the likely alterations in the definition of the score awarding principle, implying that the agencies present varying definitions of the same rating and use different measurement techniques for the same variables. Similarly, Berg et al. (2019) aimed to compare the ESG ratings by six market-leading ESG rating agencies (KLD (MSCI), Sustainalytics, Vigeo-Eiris (Moody’s), Asset4 (Refinitiv), and RobecoSAM). On average, the authors found a correlation among the scores of 0.54, ranging from 0.38 to 0.71, assessed to be low compared to the average of 0.99 correlation coefficient among the largest credit rating agencies [

4]. The discrepancy between the scores results in less ESG impact attribution to stock prices, mixed signals sent to the companies themselves, and challenges in an empirical data application. The authors concluded to explain the divergence by three main factors—(1) scope divergence—referring to various sets of attributes used by each agency, (2) weight divergence—referring to attribute weighting in the calculation of scores, and (3) measurement divergence—when agencies use different proxies for measuring the exact attributes. As the vast majority of the ESG ratings are awarded relative to a peer group, the proper definition and allocation are also crucial, however often not explicitly disclosed. Therefore the peer group selection as well might lead to deviations in the actual ESG assessment [

24].

Similar results were documented by Gibson et al. (2019) analyzing the S&P 500 companies and finding a correlation for the overall ESG score of 0.46 decreasing to the lowest for the governance dimension (0.19) and the highest for the environmental measures (0.43) [

30]. In addition, conclusions were drawn about the industry specifics of the lowest total correlations being present in the consumers and telecommunications segments, while the largest disagreement evolved in the governance scores of the financial industry companies. Furthermore, the authors found that larger companies had higher ESG score divergence.

The actual implications might result not only in the investors’ decision to invest or not, but also have a material impact on the returns. Li & Polychronopoulos (2020) analyzed the performance of two portfolios created in the US and Europe based on the assessment of two different ESG data providers. The results, despite the identical portfolio construction process, showed a difference of the cumulative performance in both portfolios of 10.0% in Europe and 24.1% in the US over 8 year period, stressing the importance of the divergence arising from the different ratings each company receives [

11]. The results imply that choosing a different ESG rating can significantly alter the investment universe and therefore also the expected returns.

2.3. ESG Rating Market Coverage in CEE

According to OECD, the market coverage of the ESG ratings is still relatively low—while in the US approximately 25% of all the public companies have an external ESG score, only 10% of the European companies have a score available [

13]. As the ESG rating availability, among other factors, strongly relies on the obtainable data, the percentage is far lower in the regions of Europe that lag in sustainability implementation. As such, only very few companies operating in the CEE region have external ESG scoring data available. A recent research used a data set comprised of all European companies, which had an ESG rating from the Thomson Reuters EIKON database as of January 2019. From the total sample of 1165 companies, 32 originated from Poland, 4 from the Czech Republic, and 4 companies from Hungary, while no other CEE countries were represented in the sample at all, highlighting the largely missing data inputs for the CEE region companies [

31]. These results are supported also by Czerwińska & Kaźmierkiewicz (2015) finding that there is a large ESG reporting gap on the Polish market, with an overall low level of reporting on non-financial data. Furthermore, the authors found that the shares issued by companies with higher ESG ratings were distinguished by an over-average return rate and lower return rate volatility [

32].

With the rise of the ESG rating availability, certain trends have emerged. The most notable is that the ESG rated investment universe is dominated by large-capitalization companies. According to OECD, the market capitalization of the ESG rated companies in the EU reached 89% in 2019 in contrast to the 10% coverage in terms of the number of companies [

5]. While there are multiple explanations related to the data availability, more resource devotion, and investor coverage, the lack of the ESG scoring poses important limitations for the smaller capitalization companies, which drift further away from the investment considerations of the investors looking for sustainable investments.

The second aspect, in parallel to the smaller size, is the relative degree of the CEE country stock exchange under development. According to Koke & Schroder (2002), from all the CEE stock exchanges only the Warsaw Stock Exchange could be comparable to the smallest Western European exchange (Vienna), while the remaining CEE stock exchanges have comparatively very low market capitalization—both in absolute terms and relative to GDP [

33]. Several of the CEE exchanges belong to the smallest exchanges in the world implying also the negligible contribution to the total global capitalization level.

3. Data

To examine the rating availability and the variances in the scores of different ESG rating agencies in the first part of the research, the authors retrieved the available scores from the Bloomberg database. As of March 2021, Bloomberg offered the following third-party ESG Scores—ISS Quality Score, RobecoSAM rating, Sustainalytics ESG score, and MSCI ESG rating. In addition, Bloomberg’s own ESG disclosure score was obtained. A sample of 6001 largest European publicly listed companies was retrieved, indicating their industry as of GICS classification, primary listing exchange, and the aforementioned ESG scores. EU, UK and Switzerland listed companies were selected as they have an arguably similar legal framework of operations and do not have inconsolable geographical differences creating incomparable materiality differences.

Next, for the second part of the research, to explore the rating availability in the less developed geographies, a sample of 2000 largest CEE country stock-exchange listed companies was selected. The reason for choosing CEE companies as the analytical sample was the intention to focus on the emerging region, where ESG factors have been of a lower priority compared to the more developed regions of Europe. The quantifiable ESG scoring data (RobecoSAM, Sustainalytics, and MSCI) were retrieved for the sample companies listed in Bratislava, Bucharest, Budapest, Ljubljana, Prague, Riga, Tallinn, Sofia, Vilnius, Warsaw, and Zagreb. In addition to the ESG scores, the retrieved data were supplemented with entity industry markers as per GICS classification, primary listing exchange, market capitalization data, 3 months average trading volume as well as 6 and 12 months returns. Only those CEE countries being a member of the EU were chosen due to the similar ESG disclosure requirements.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. European Company Rating Availability

The overview of the ESG ratings obtained is presented in

Table 1.

As indicated in

Table 2, from a maximum of five different sustainability related scores, the vast majority or 72% of the European sample companies had none.

The ESG data and scoring availability has been cited as one of the most common obstacles, which hinders investors’ efforts to apply ESG data in their investment decisions (35). The results on the European listed companies strongly highlight this problem as the 72% of companies with no external ESG rating are likely to be excluded from the investment universe of those asset managers, who shall rely on a third-party sustainability evaluation for their investment policies. Only 205 European listed companies (or 3% of the sample) had all the selected scores available, the most common measure being the ISS Quality score, which, however, speaks of only the governance facet of the ESG metric. The next most popular—Bloomberg’s ESG disclosure score is available for 15% of the sample companies, however, this measure also does not offer a full scope ESG evaluation and rather measures only the degree of the company’s transparency instead of the actual performance. The three latter measures, RobecoSAM, Sustainalytics, and MSCI ESG ratings, are available for 14%, 8%, and 6% of the sample companies, respectively.

4.2. Score Divergence

Do the ratings tell the same story? Do investors, which already have their investment universe limited by the rating availability at least face a coherent evaluation?

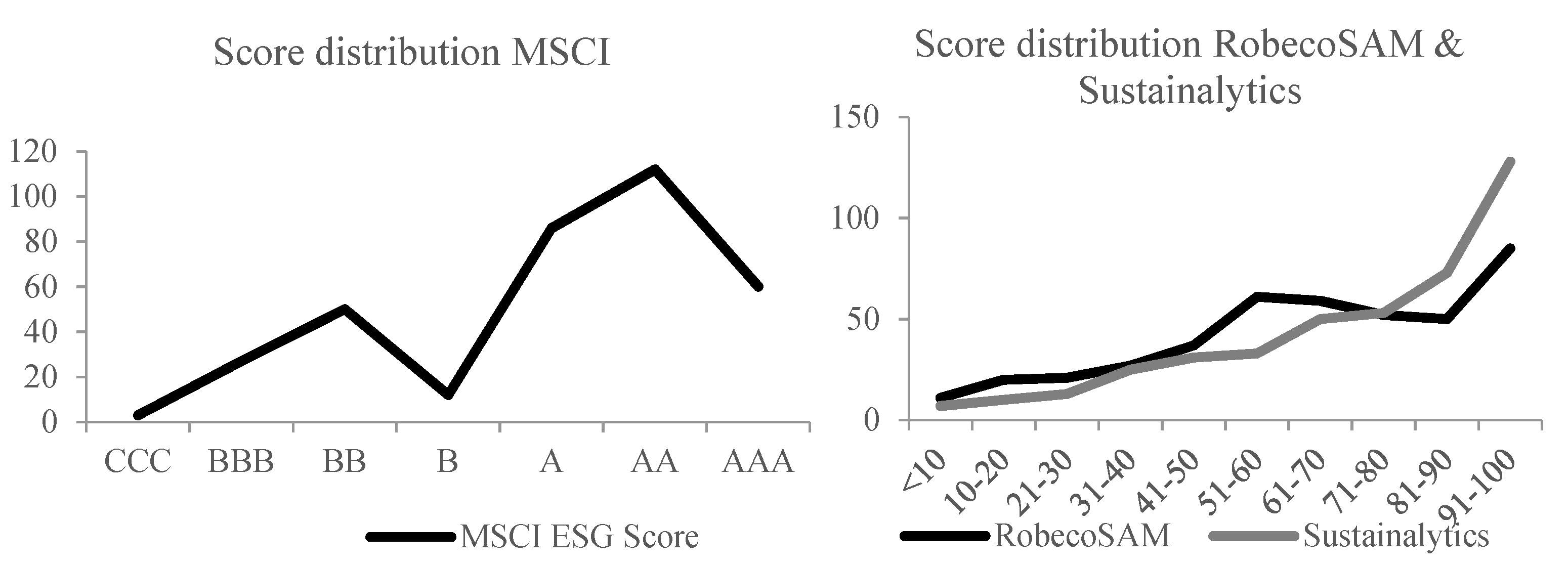

As Sustainalytics and RobecoSAM ratings are expressed on the same scale of 100, they provide the most straightforward comparison. By comparing the score distribution in

Figure 1, a similar picture emerges as most of the rated sample companies have achieved a score of the highest decile (above 90). While RobecoSAM scores are spread more evenly between, Sustainalytics scores show a more definite uptrend. These results are slightly different from the study by Lopez & Bendix (2020), who used a global sample of 2000 largest market capitalization companies and found an even distribution of these ratings. Consequently, data shows that the European sample has a higher concentration of high-scoring companies. Furthermore, MSCI ESG Scores show that the majority (74%) of the sample companies have received one of the highest categories (A and above).

To perform correlation analysis, ISS and MSCI scores were expressed on a 100 point scale. The pairwise correlations, summarized in

Table 3, confirm the highest correlation between RobecoSAM and Sustainalytics ratings (0.58). The result for the European sample is lower than previously reported by Lopez and Bendix (reporting 0.72) and Berg et al. (reporting 0.65). Furthermore, the Bloomberg disclosure score shows a relatively high agreement with these scores—0.51 and 0.59, respectively, confirming that the Bloomberg score’s data disclosure level relates positively to the third-party ratings. ISS corporate governance score, as expected, has a low correlation with the other scores, which is logical as only one of the ESG dimensions is assessed by the ISS.

In order to deeper analyze the sources of the differences, the industry comparisons between the most analogous RobecoSAM and Sustainalytics scores were undertaken. In absolute terms, the score divergence on the single entity level reached even up to 85 points of 100. Of 424 companies that had both scores available for comparison, 40% had an absolute score difference of more than 20 points. When comparing across industries, the most frequent differences were found for the banks (average difference of 34 points), chemicals (average difference of 40 points), and machinery.

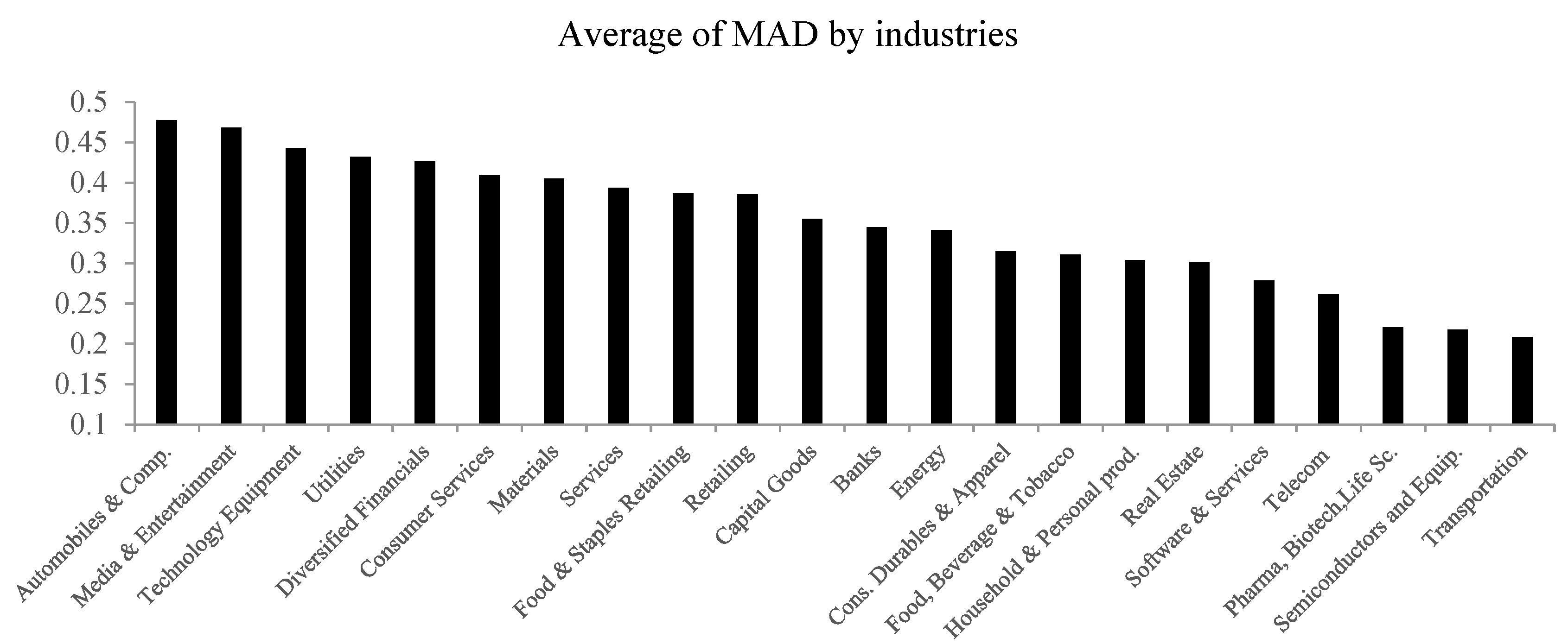

In line with the methodology employed by Berg et al. (2019), in order to estimate the heterogeneity of the score divergence, the mean absolute distance (MAD) of the single entity’s score to the average rating of the company was calculated. The sample values were normalized, and the mean absolute distance was calculated for each entity. By using the normalized data, the interpretation of MAD in terms of standard deviations was possible. The average MAD of the sample was 0.36, with a median of 0.29, which was slightly below the values found by Berg et al. (0.49 and 0.45), supporting the argument that European companies on average have lower score divergence due to more comparable geographical factors and legal requirements in place (See

Figure 2).

The highest divergence was found for the automobiles and components industry, media and entertainment, as well as technology and utilities. The results on the industries are hardly comparable and no clear trends can be seen, thus it is challenging to draw some overarching conclusions. Contrary to the previous results by Gibson et al. (2019), who found that sectors with a higher level of agreement among ratings e.g., financials, technology, and consumer goods, seem to place less emphasis on environmental factors, the results for the European sample are less telling [

31].

All in all, as each of the scoring methods, uses a different set of input data as well as weights and approaches in aggregating the information, the divergence in the ratings of European companies is significant even when taking into account the similar reporting and disclosing requirements of the EU.

Geographical Differences—CEE Analysis

Based on the listed stock exchanges, 72% of all the rating scores available in the sample were granted to companies listed in the UK, Germany, France, Sweden, Italy, and Switzerland. Meanwhile, the remaining European countries, especially the CEE region companies have extremely low external ESG rating coverage—companies of the 11 CEE countries contributed in total only 4% of the total score count, which indicates a rather strong disadvantage to the sustainable investments that could be flowing into these geographies.

While academic evidence shows that companies in this part of Europe are strongly working towards developing their ESG disclosure practices and more ESG disclosure documentation is publicly available for the stock listed companies, the evidence suggests that the efforts are still not sufficiently appreciated [

34,

35]. As depicted in

Table 4 from a maximum of three different sustainability-related scores (Sustainalytics, RobecoSAM, and MSCI), 97% of the sample companies had none. In line with the findings of Boffo & Patalano (2020), when measured by the market capitalization, however, the companies having at least one ESG rating covered 88% of the total market capitalization of the entire sample, implying the significant impact of the size on the external ESG score availability.

The most common score available for the CEE companies was the RobecoSAM sustainability ranking (available to 54 companies), the MSCI ESG score was available to 19 companies, while the Sustainalytics score was awarded to only 7 CEE listed companies. Consequently, the sub-sample of the 54 companies having RobecoSAM rating was chosen for further analysis. As noted before, the ESG score by RobecoSAM aims to account for previously in the academic literature described biases due to differences in geography, company size, and disclosure level. The adjustments to these differences are done by comparing only those peers with similar sectoral and geographical backgrounds (18).

The ESG-scored sub-sample consists of 54 companies—42 of them listed in Warsaw, 6 in Budapest, and one in Prague and Bucharest, each. The average sustainability ranking of the companies was 27.4, which is 21 points lower than the average European score indicating the still developing practice and compliance to the ESG metrics in this region.

Next, to test whether some implications of the lack of the ESG rating are already visible between the companies having external ESG scores and not, a synthetic sample of 54 CEE companies having no external ESG ratings was selected. It was attempted to create the sample close to the original one—the same geographic split, industry breakdown, and market capitalization. Albeit, the similar split sub-sample depicted in

Table 5 offered significantly lower average market capitalization (169bn EUR vs. 9bn EUR).

Independent sample

t-tests were carried out to evaluate the potential differences in the returns and trading volume. As the first step, F-tests were carried out to determine the differences in variances of the samples. Next,

Table 6 below shows the results of all the

t-tests performed.

The results indeed show a significant difference (significant at 99%) of the average trading volume implying a significantly higher share turnover and consequently higher liquidity for the companies having an external ESG score. Nevertheless, as the average market capitalization rates of both sub-samples were so diverse, it is impossible to conclude whether the results are not attributable to the size premium in terms of the rating availability for the higher capitalized companies. Additional two sub-samples were therefore created to account for the possible differences in the market capitalization by removing the largest companies from the ESG sample. Two company groups (see

Table 7) with a similar average market capitalization rate and each consisting of 46 companies were created.

The differences are visible also in the geographical split, as several largely capitalized companies in the non-ESG sub-sample are listed on the Budapest stock exchange, however, a large share of them seem to lack the ESG score (in contrast, to their Warsaw-listed peers). The results of the

t-tests in

Table 8 indicate similar results to the first specification, meaning that also by removing the market capitalization effect, the trading volume is lower for the companies without the ESG scores, confirming the negative liquidity effect coming from the lack of the ESG score. No significant differences in the returns of the equities were found.

The results underline the disadvantage of the companies, which do not have an external ESG score, resulting in a lower trading volume. This finding is especially important for the companies listed in the CEE stock exchanges, as the financial markets there are underdeveloped relative to their Western European peers and lack liquidity, therefore the investors often tend to look skeptically towards investments there.

5. Conclusions

The global trend towards responsible investing leads to an increase in the demand for ESG data conveniently provided by the ESG rating agencies. Two important challenges related to these ratings are currently present—firstly, the availability of the scores and secondly, the divergence among them. The present study, firstly, contributes to the ESG rating-related literature by comparing the various ESG scores awarded to European stock-listed companies. It is found that 72% of the companies have no external ESG rating imposing a threat of a likely exclusion from the investment universe of those asset managers who shall rely on the third-party sustainability evaluation for their investment policies. Data shows that the European sample has a higher concentration of high-scoring companies than previously found by Lopez & Bendix (2020) from a global sample.

A correlation of 0.58 is found between the two most comparable ESG ratings (RobecoSAM and Sustainalytics) implying that the ESG rating divergence is high even among those European companies having a similar set of underlying sustainability disclosure regulations. Albeit, the mean absolute distance of the single entity scores is found to be lower (0.36) than found by Berg et al. (2019) for the global sample (0.49) implying that the European companies on average have a lower score divergence due to more comparable geographical factors and legal requirements in place. Because of the ESG score differences it is crucial for investors to understand the historical set up and the broad methodology of the rating agencies, whose scores they would like to use, in order to understand their focus points and emphasis. As long as the agencies are transparent about their approaches and information evaluation mechanisms, and investors and firms are educated about the potential differences, it shall be possible to decide which ratings line up the closest with their views and priorities.

In addition, the analysis of the rating availability of the CEE companies was used to test whether there are liquidity benefits provided from having an external ESG score. Independent t-test analysis between the sample of companies having the ranking and a sample of unranked companies was performed and confirmed that even when removing the potential market capitalization effect, the unranked companies had lower trading volume than their ESG-ranked peers. Given the average sustainability ranking of the CEE companies of 27.4, 21 points less than the average European score, it is clear that the still-developing practices and compliance to the ESG metrics is still emerging in this region. The investors and companies themselves shall therefore be aware of the implied liquidity effects coming from the lack of the ESG score.

This study also confirms Boffo & Patalano (2020) conclusions that the rate of the ESG rating availability is significantly higher when measured by the market capitalization implying that there is a trend in the favor of the larger market capitalization companies to be awarded an ESG score and thus further deviating the investment universe away from the smaller peers with fewer resources to devote to sustainability implementation and reporting. This is an especially important finding and consideration for such emerging economies as the CEE countries, where the limits in company size and degree of financial market development hinder the external ESG score availability, thus limiting also the emergence of the CEE companies as the potential investment targets of the sustainability-targeted investors.