Difficulties for Teleworking of Public Employees in the Spanish Public Administration

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No | Variable | Values |

|---|---|---|

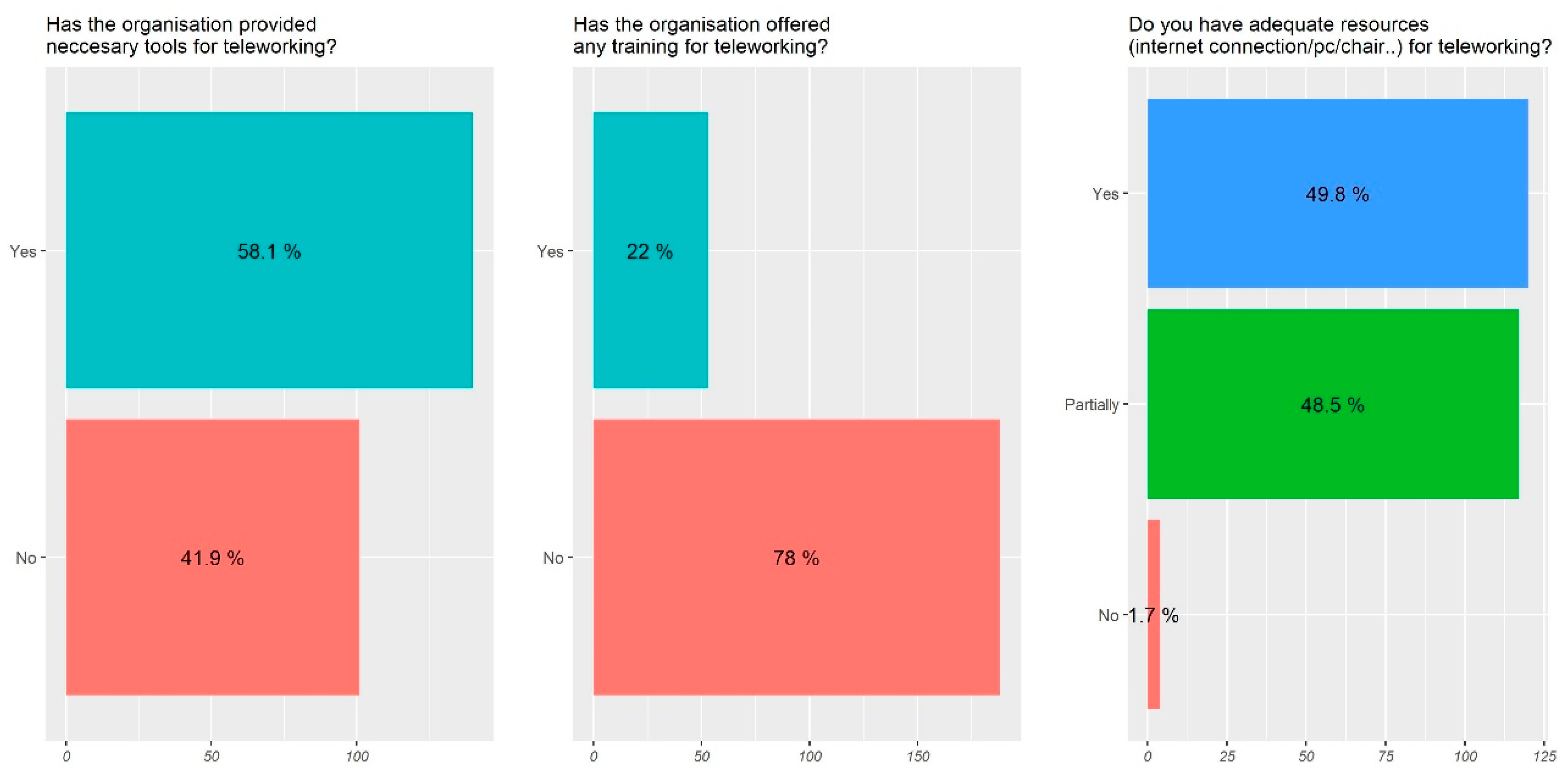

| 1 | Has the organization provided any tools for teleworking? | 1. No |

| 2. Yes | ||

| 2 | Has the organization offered any training for teleworking? | 1. No |

| 2. Yes | ||

| 3 | Do you have adequate resources (internet connection/computer/chair …) for teleworking? | 1. No |

| 2. Partially | ||

| 3. Yes | ||

| 4 | Children | 1. No |

| 2. Yes | ||

| 5 | Sex | 1. Men |

| 2. Women | ||

| 6 | Living_Couple | 1. No |

| 2. Yes | ||

| 7 | Executive Level | 1. No |

| 2. Yes | ||

| 8 | Wrong postures | 1. No |

| 2. Yes | ||

| 9 | Social isolation | 1. No |

| 2. Yes | ||

| 10 | Lack of motivation | 1. No |

| 2. Yes | ||

| 11 | Communication with colleagues | 1. No |

| 2. Yes | ||

| 12 | Cannot disconnect from work | 1. No |

| 2. Yes | ||

| 13 | Space problems | 1. No |

| 2. Yes | ||

| 14 | Interruptions | 1. No |

| 2. Yes | ||

| 15 | Deficient internet connection | 1. No |

| 2. Yes |

| p-Value | Executive Role | Children | Sex | Living as a Couple |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wrong postures | 0.1038 | 0.1866 | 2.25 × 10−2 * | 0.3531 |

| Social isolation | 0.9463 | 4.26 × 10−2 * | 6.69 × 10−2 · | 3.82 × 10−3 ** |

| Lack of motivation | 0.3622 | 0.3445 | 0.4576 | 9.35 × 10−3 ** |

| Communication with colleagues | 0.9463 | 0.9449 | 5.12 × 10−2 · | 0.1894 |

| Cannot disconnect from work | 1.34 × 10−2 * | 8.21 × 10−2 · | 0.8538 | 0.8639 |

| Space problems | 0.1043 | 0.8095 | 2.59 × 10−2 * | 0.5624 |

| Interruptions | 0.2531 | 7.05 × 10−5 *** | 0.3905 | 0.2146 |

References

- Martínez Morán, P.C.; Diez Ruiz, F. Cinco Cambios en las Relaciones Laborales Provocadas por el Coronavirus. The Conversation. Available online: https://theconversation.com/cinco-cambios-en-las-relaciones-laborales-provocados-por-el-coronavirus-142023 (accessed on 19 July 2020).

- ILO. El Teletrabajo Durante la Pandemia de COVID-19 y Después de ella: Guía Práctica. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/WCMS_758007/lang--es/index.htm (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- ILO. Observatorio de la OIT: La COVID-19 y el Mundo del Trabajo. Séptima Edición. Estimaciones Actualizadas y Análisis. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_767045.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- Anghel, B.; Cozzolino, M.; Lacuesta, A. El teletrabajo en España. Boletín Económico 2020, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Employed Persons Working from Home as a Percentage of the Total Employment, by Sex, Age, and Professional Status (%). Available online: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Bangemann, I. Europa y la Sociedad de la Información Planetaria; Recomendaciones al Consejo Europeo: Bruselas, Belgium, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Acuerdo Marco Europeo Sobre Teletrabajo, Brussels, Belgium. 2002. Available online: https://www.uned.ac.cr/viplan/images/acuerdo-marco-europeo-sobre-teletrabajo.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Eraso, A.G.B. Teletrabajo en España: Acuerdo marco y Administración Pública. RIO Rev. Int. Organ. 2008, 1, 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Peiró, J.M.; Soler, A. El Impulso al Teletrabajo Durante el COVID-19 y los Retos Que Plantea, IvieLab. 2020. Available online: https://www.ivie.es/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/11.Covid19IvieExpress.El-impulso-al-teletrabajo-durante-el-COVID-19-y-los-retos-que-plantea.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Poquet, R. Balance de un Año de Teletrabajo en España. The Conversation. Available online: https://theconversation.com/balance-de-un-ano-de-teletrabajo-en-espana-153864 (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Sebastián, R. Teletrabajo en España: De Dónde Venimos y a Dónde Vamos. Esade. Available online: https://dobetter.esade.edu/es/teletrabajo-espana?_wrapper_format=html (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Real Decreto Legislativo 2/2015, de 23 de Octubre, Por el Que se Aprueba el Texto Refundido de la Ley del Estatuto de los Trabajadores; BOE: Madrid, Spain, 2015.

- Real Decreto-Ley 28/2020, de 22 de Septiembre, de Trabajo a Distancia; BOE: Madrid, Spain, 2000.

- Rastrollo, J.J. Deben de Tener Derecho a Teletrabajar los Empleados Públicos? The Conversation. Available online: https://theconversation.com/deben-tener-derecho-a-teletrabajar-los-empleados-publicos-145660 (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Ministerio de Política Territorial y Función Pública. Boletín Estadístico del Personal al Servicio de las Administraciones Públicas, Ministerio de Política Territorial y Función Pública. 2020. Available online: https://www.hacienda.gob.es/CDI/Empleo_Publico/Boletin_rcp/bol_semestral_201901_completo.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Ministerio de Política Territorial y Función Pública. Available online: https://www.mptfp.gob.es/dam/es/portal/funcionpublica/secretaria-general-funcion-publica/Actualidad/2020/06/2020-06-17/Resolucion.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Bermúdez, A.P.; Fuentes, P.N. El futuro del trabajo en la Administración Pública: ¿Estamos preparados? Pertsonak Antolakunde Publikoak Kudeatzeko Euskal Aldizka. Rev. Vasca Gestión Pers. Organ. Públicas 2019, 3, 34–51. [Google Scholar]

- BOE. Real Decreto Legislativo 5/2015, de 30 de Octubre, Por el Que se Aprueba el Texto Refundido de la Ley del Estatuto Básico del Empleado Público; BOE: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Real Decreto 364/1995, de 10 de Marzo, por el que se Aprueba el Reglamento General de Ingreso del Personal al Servicio de la Administración general del Estado y de Provisión de Puestos de Trabajo y Promoción Profesional de los Funcionarios Civiles de la Administración General del Estado; BOE: Madrid, Spain, 1995.

- Orden APU/3902/2005, de 15 de Diciembre, Por la Que se Dispone la Publicación del Acuerdo de la Mesa General de Negociación Por el Que se Establecen Medidas Retributivas y Para la Mejora de las Condiciones de Trabajo y la Profesionalización de los Empleados Públicos; BOE: Madrid, Spain, 2005.

- Orden APU/1981/2006, de 21 de Junio, Por la Que se Promueve la Implantación de Programas Piloto de Teletrabajo en los Departamentos Ministeriales; BOE: Madrid, Spain, 2006.

- González Bermejo, A. El Teletrabajo Como Nuevo Método en el Empleo Público: Propuesta de Plan Piloto. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Morón, M.S. El empleo público en España: Problemas actuales y retos de futuro. Rev. Aragón. Adm. Pública 2011, 13, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Thibault, J. El Teletrabajo. In Análisis Jurídico Laboral; CES: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chaparro, F.O.; Morán, J.M. El Teletrabajo: Una Nueva Sociedad Laboral en la era de la Tecnología; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios, R.S. El teletrabajo. Derecho PUCP 2007, 60, 325–350. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, T.H.; Pearlson, K. Two cheers for the virtual office. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 1998, 39, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Gaeta, L. Teletrabajo y derecho: La experiencia italiana. Doc. Labor. 1996, 49, 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Huws, U.; Robinson, W.B.; Robinson, S. Telework towards the Elusive Office; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Thibault, J. Teletrabajo y ordenación del tiempo de trabajo. In Proceedings of the JIS’2000: III Jornadas Sobre Informática y Sociedad, Madrid, Spain, 30 March–1 April 2001; pp. 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo, O. Teletrabajo del lugar al que voy a las tareas que realizo. Debates IESA 2001, 16, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, M.P.; Sánchez, A.M.; de Luis Carnicer, M.P.; Jiménez, M.J.V. La adopción del teletrabajo y las tecnologías de la información: Estudio de relaciones y efectos organizativos. Rev. Econ. Empresa 2004, 22, 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Caamaño Rojo, E. El teletrabajo como una alternativa para promover y facilitar la conciliación de responsabilidades laborales y familiares. Rev. Derecho 2010, 35, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mokhtarian, P.L.; Salomon, I. Modeling the desire to telecommute: The importance of attitudinal factors in behavioral models. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 1997, 31, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aderaldo, I.L.; Aderaldo, C.V.L.; Lima, A.C. Aspectos críticos do teletrabalho em uma companhia multinacional. Cad. EBAPE Br. 2017, 15, 511–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nilles, J.M. Traffic reduction by telecommuting: A status review and selected bibliography. Transp. Res. Part A Gen. 1988, 22, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beňo, M. The Advantages and Disadvantages of E-working: An Examination using an ALDINE Analysis. Emerg. Sci. J. 2021, 5, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsen, C.; van Veldhoven, M.; Kirchner, K.; Hansen, J.P. Six Key Advantages and Disadvantages of Working from Home in Europe during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtarian, P.L.; Bagley, M.N.; Salomon, I. The impact of gender, occupation, and presence of children on telecommuting motivations and constraints. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1998, 49, 1115–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boys, J. Megatrends: Working from Home: What’s Driving the Rise in Remote Working? 2020. Available online: https://www.cipd.co.uk/Images/working-from-home-1_tcm18-74230.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Holgersen, H.; Jia, Z.; Svenkerud, S. Who and how many can work from home? Evidence from task descriptions. J. Labour Mark. Res. 2021, 55, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Adams-Prassl, A.; Boneva, T.; Golin, M.; Rauh, C. Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: Evidence from real time surveys. J. Public Econ. 2020, 189, 104245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belzunegui-Eraso, A.; Erro-Garcés, A. Teleworking in the Context of the COVID-19 Crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, A.; Pallais, A. Valuing alternative work arrangements. Am. Econ. Rev. 2017, 107, 3722–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Troup, C.; Rose, J. Working from home: Do formal or informal telework arrangements provide better work–family outcomes? Community Work. Fam. 2012, 15, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caillier, J.G. The impact of teleworking on work motivation in a US federal government agency. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2012, 42, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, H.; Tummers, L.; Bekkers, V. The benefits of teleworking in the public sector: Reality or rhetoric? Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2019, 39, 570–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goldin, C. A grand gender convergence: Its last chapter. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 1091–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ishizuka, P.; Musick, K. Occupational Characteristics and Women’s Employment during the Transition to Parenthood. Demography 2021, 58, 1249–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornick, J.C.; Meyers, M.K. Families That Work: Policies for Reconciling Parenthood and Employment; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit, B.; Hook, J.L. Gendered Tradeoffs: Women, Family, and Workplace Inequality in Twenty-One Countries; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, A.M.; Silva, J.R.G.D. Percepções dos indivíduos sobre as consequências do teletrabalho na configuração home-office: Estudo de caso na Shell Brasil. Cad. EBAPE Br. 2010, 8, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, I.D.S.A. Control in contemporary work arrangements: Teleworkers and the enterprise of the self’discourse/Controle em novas formas de trabalho: Teletrabalhadores e o discurso do empreendedorismo de si. Cad. EBAPE Br. 2013, 11, 462–475. [Google Scholar]

- Nohara, J.J.; Acevedo, C.R.; Ribeiro, A.F.; da Silva, M.M. O teletrabalho na percepção dos teletrabalhadores. INMR-Innov. Manag. Rev. 2010, 7, 150–170. [Google Scholar]

- Gálvez, A.; Tirado, F.; Alcaraz, J.M. “Oh! Teleworking!” Regimes of engagement and the lived experience of female Spanish teleworkers. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2020, 29, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dockery, A.M.; Bawa, S. Is working from home good work or bad work? Evidence from Australian employees. Aust. J. Labour Econ. 2014, 17, 163–190. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, C.P.; Mozo, A.M.G. Teletrabajo y vida cotidiana: Ventajas y dificultades para la conciliación de la vida laboral, personal y familiar [Telework and daily life: Its pros and cons for work-life balance]. Athenea Digit. 2009, 15, 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, C.P. El teletrabajo: ¿Más libertad o una nueva forma de esclavitud para los trabajadores? IDP. Rev. Internet Derecho Política 2010, 11, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bartol, X.; Ramos, R. COVID-19 y Mercado de Trabajo: Teletrabajo, Largas Jornadas y Salud Mental. Asociación Libre de Economía, 2020. Available online: https://alde.es/blog/covid-19-y-mercado-de-trabajo-teletrabajolargas-jornadas-y-salud-mental/ (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Olson, M.H.; Primps, S.B. Working at home with computers: Work and nonwork issues. J. Soc. Issues 1984, 40, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, S.J.; Choi, N.; Sung, W. The use of smart work in government: Empirical analysis of Korean experiences. Gov. Inf. Q. 2016, 33, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpaz, I. Advantages and disadvantages of telecommuting for the individual, organization and society. Work Study 2002, 51, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilton, R.D.; Páez, A.; Scott, D.M. Why do you care what other people think? A qualitative investigation of social influence and telecommuting. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2011, 45, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.; Muñoz, G. Teletrabajo: Productividad y bienestar en tiempos de crisis. Esc. Psicol. 2020, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, N.B.K.D.E.; Kurland, N.B. The advantages and challenges of working here, there, anywhere, and anytime. Organ. Dyn. 1999, 28, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Filardi, F.; Castro, R.M.P.; Zanini, M.T.F. Advantages and disadvantages of teleworking in Brazilian public administration: Analysis of SERPRO and Federal Revenue experiences. Cad. EBAPE Br. 2020, 18, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scott, D.M.; Dam, I.; Páez, A.; Wilton, R.D. Investigating the effects of social influence on the choice to telework. Environ. Plan. A 2012, 44, 1016–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, M.A.; Bellini, C.G.P.; Donaire, D.; dos Santos, S.A.; Mello, Á.A.A. Teletrabalho no desenvolvimento de sistemas: Um estudo sobre o perfil dos teletrabalhadores do conhecimento. Rev. Ciências Adm. 2011, 17, 1029–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Limón, E.Y. La situación actual y el futuro del teletrabajo en el Perú. Not. CIELO 2021, 1, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Behrens, K.; Kichko, S.; Thisse, J.F. Working from Home: Too Much of a Good Thing? 2021. Available online: https://www.cesifo.org/en/publikationen/2021/working-paper/working-home-too-much-good-thing (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Beltrán, A.R.P.; Bilous, A.; Flores, J.C.; Escobar, C.F.B. El impacto del teletrabajo y la administración de empresas. Recimundo Rev. Cient. Investig. Conoc. 2020, 4, 326–335. [Google Scholar]

- Barandiarán, A. El Correo. Available online: https://www.elcorreo.com/economia/negociaciones-implantar-teletrabajo-20210419215316-nt.html?ref=https:%2F%2Fwww.elcorreo.com%2Feconomia%2Fnegociaciones-implantar-teletrabajo-20210419215316-nt.html (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Equipos y Talento. Los Españoles se Gastaron 615 Euros en Equipamiento Para Teletrabajar. Available online: https://www.elmundofinanciero.com/noticia/92853/empresas/los-espanoles-se-gastaron-615-euros-en-equipamiento-para-teletrabajar-durante-la-pandemia.html (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Equipos y Talento. Teletrabajo: Incremento de los Gastos del Hogar. Available online: https://www.equiposytalento.com/fotoretribucion/teletrabajo-incremento-de-los-gastos-del-hogar (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Aguado, D. ¿Cómo Analizar la Nueva Realidad del Teletrabajo?—IIC (uam.es). Available online: https://www.iic.uam.es/rr-hh/como-analizar-realidad-del-teletrabajo/ (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Dos Santos Soares, A. Teletrabalho e comunicaçao em grandes CPDs. Rev. Adm. Empresas 1995, 35, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tremblay, D.G. Organização e satisfação no contexto do teletrabalho. Rev. Adm. Empresas 2002, 42, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- IEBS Business School. El Futuro del Teletrabajo en la Nueva Normalidad. 2021. Available online: https://www.masquenegocio.com/2020/12/07/futuro-teletrabajo-nueva-normalidad/ (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Baruch, Y. Teleworking: Benefits and pitfalls as perceived by professionals and managers. New Technol. Work. Employ. 2000, 15, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasic, M. Challenges of teleworking during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anal. Ekon. Fak. Subotici 2020, 56, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, M. Two Third of Employees in Pain Working from Home. HR Magazin. Available online: https://www.hrmagazine.co.uk/content/news/two-thirds-of-employees-in-pain-working-from-home (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Kumar, N. The Times Hub. Available online: https://thetimeshub.in/teleworking-avoiding-the-ailments-associated-with-bad-posture/3316/ (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Maurer, R. Neglecting Economics Safety for Teleworkers Can Be Costly. SHRM, 2021. Available online: https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/risk-management/pages/ergonomicssafetyforteleworkers.aspx (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Lodovici, M.S. The Impact of Teleworking and Digital Work on Workers and Society. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/662904/IPOL_STU(2021)662904_EN.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Kwon, M.; Jeon, S.H. Do Leadership Commitment and Performance-Oriented Culture Matter for Federal Teleworker Satisfaction With Telework Programs? Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2020, 40, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, B. Resultados de la Encuesta Sobre el Impacto del Teletrabajo en las Mujeres, Asociación de Mujeres en el Sector Público. 2020. Available online: mujeresenelsectorpublico.com (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Capolongo, S.; Rebecchi, A.; Buffoli, M.; Appolloni, L.; Signorelli, C.; Fara, G.M.; D’Alessandro, D. COVID-19 and cities: From urban health strategies to the pandemic challenge. A decalogue of public health opportunities. Acta Biomed. Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Camerin, F. Open issues and opportunities to guarantee the “right to the ‘healthy’city” in the post-Covid-19 European city. Contesti. Città Territ. Progett. 2020, 2, 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Fabris, L.M.F.; Camerin, F.; Semprebon, G.; Balzarotti, R.M. New Healthy Settlements Responding to Pandemic Outbreaks: Approaches from (and for) the Global City. Plan J. 2020, 5, 385–406. [Google Scholar]

- Eric, C.; Laura, C.; Enrico, F.; Gianni, G.; Enrico, L.; Laura, P.M.; Sergio, V. Effects of Air Pollution on COVID-19 Related Mortality in Northern Italy; Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei (FEEM): Milan, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Honey-Rosés, J.; Anguelovski, I.; Chireh, V.K.; Daher, C.; Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C.; Litt, J.S.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. The impact of COVID-19 on public space: An early review of the emerging questions–design, perceptions and inequities. Cities Health 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2013; Available online: http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An {R} Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://socialsciences.mcmaster.ca/jfox/Books/Companion/ (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation; R Package Version 1.0.2. 2020. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Wickham, H.; Bryan, J. readxl: Read Excel Files; R Package Version 1.3.1. 2019. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=readxl (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Fox, J. RcmdrMisc: R Commander Miscellaneous Functions; R Package Version 2.7-1. 2020. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=RcmdrMisc (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Comtois, D. Summarytools: Tools to Quickly and Neatly Summarize Data; R Package Version 0.9.9. 2021. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=summarytools (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Delacre, M.; Lakens, D.; Leys, C. Why psychologists should by default use Welch’s t-test instead of Student’s t-test. Int. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 30, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newbold, P.; Carlson, W.L.; Thorne, B. Statistics for Business and Economics; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Country | Percentage of Employed Men Who Work from Home | Percentage of Employed Women Working from Home |

|---|---|---|

| Finland | 24.8% | 25.5% |

| Luxembourg | 22.5% | 23.9% |

| Ireland | 21.3% | 21.7% |

| Spain | 9.9% | 12.1% |

| EU-27 average | 11.5% | 13.2% |

| Group | Subgroup | Occupant Profile | Type of Position | Levels |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | A1 | Bachelor’s degree, Engineer, Architect or equivalent | Direction, execution, control, and study. | Minimum, 20. Maximum, 30 |

| B | A2 | Diploma, Technical Engineering, Technical Architecture or equivalent | Management and collaboration in administrative functions. | Minimum, 16. Maximum, 26 |

| C | C1 | High school diploma, intermediate vocational training or vocational training technician, high school diploma, FP2 or equivalent. | Administrative body | Minimum, 11. Maximum, 22 |

| D | C2 | ESO, school graduate, FP1 or equivalent | Assistant | Minimum, 9. Maximum, 18 |

| E | No degree required | Surveillance and custody | Minimum, 7. Maximum, 14 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ortiz-Lozano, J.M.; Martínez-Morán, P.C.; Fernández-Muñoz, I. Difficulties for Teleworking of Public Employees in the Spanish Public Administration. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8931. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168931

Ortiz-Lozano JM, Martínez-Morán PC, Fernández-Muñoz I. Difficulties for Teleworking of Public Employees in the Spanish Public Administration. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):8931. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168931

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrtiz-Lozano, José María, Pedro César Martínez-Morán, and Iván Fernández-Muñoz. 2021. "Difficulties for Teleworking of Public Employees in the Spanish Public Administration" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 8931. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168931

APA StyleOrtiz-Lozano, J. M., Martínez-Morán, P. C., & Fernández-Muñoz, I. (2021). Difficulties for Teleworking of Public Employees in the Spanish Public Administration. Sustainability, 13(16), 8931. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168931