Factors Affecting the Intention of Multi-Family House Residents to Age in Place in a Potential Naturally Occurring Retirement Community of Seoul in South Korea

Abstract

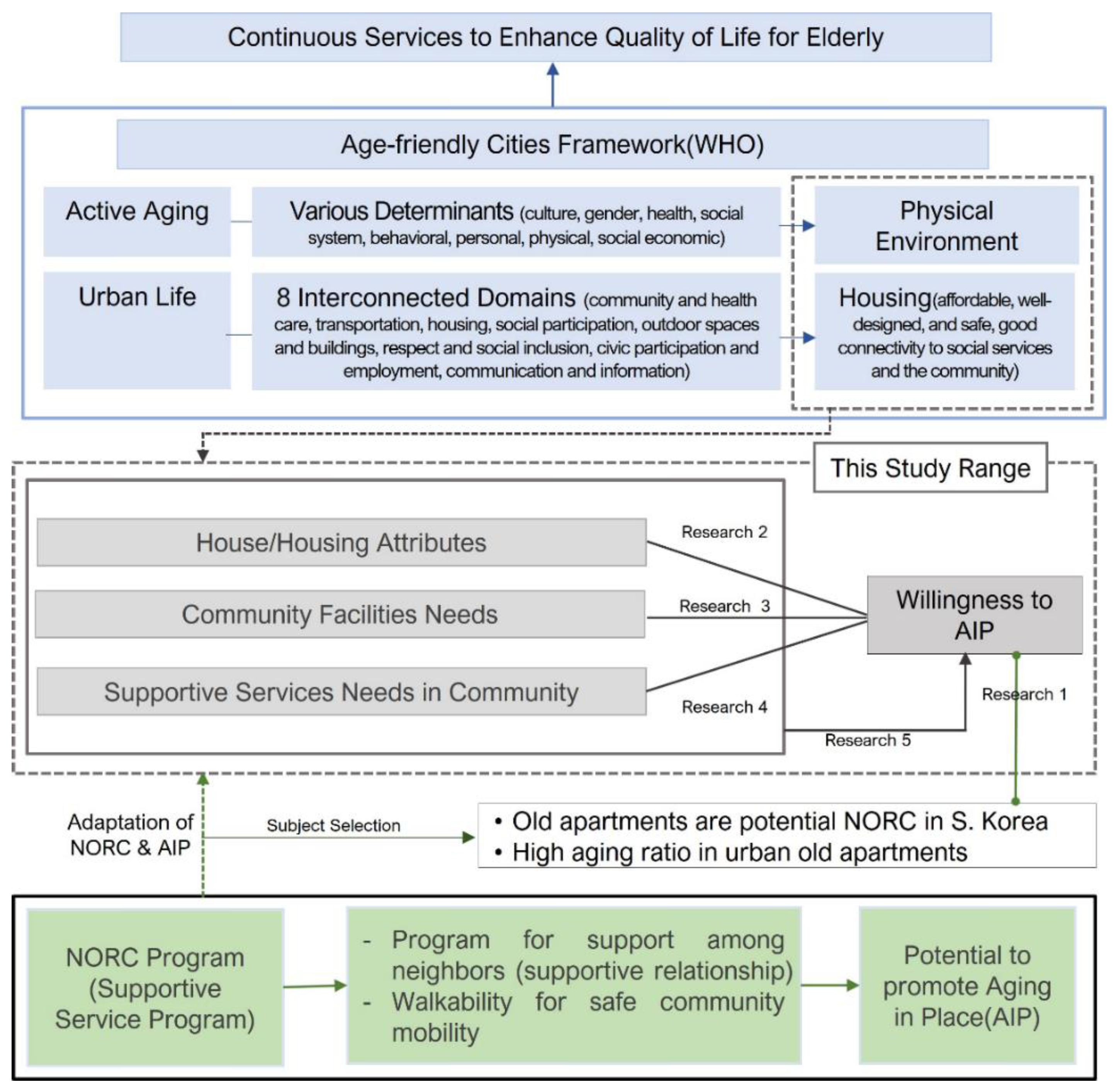

:1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Research Purpose

- First, what is resident willingness to age in place, and what are the reasons for it?

- Second, what are the housing attributes that relate to resident AIP?

- Third, what community facilities needs are relevant to resident AIP?

- Fourth, what service needs are relevant to resident AIP?

- Fifth, among housing, community facility needs, and service needs factors, what predictors affect resident AIP?

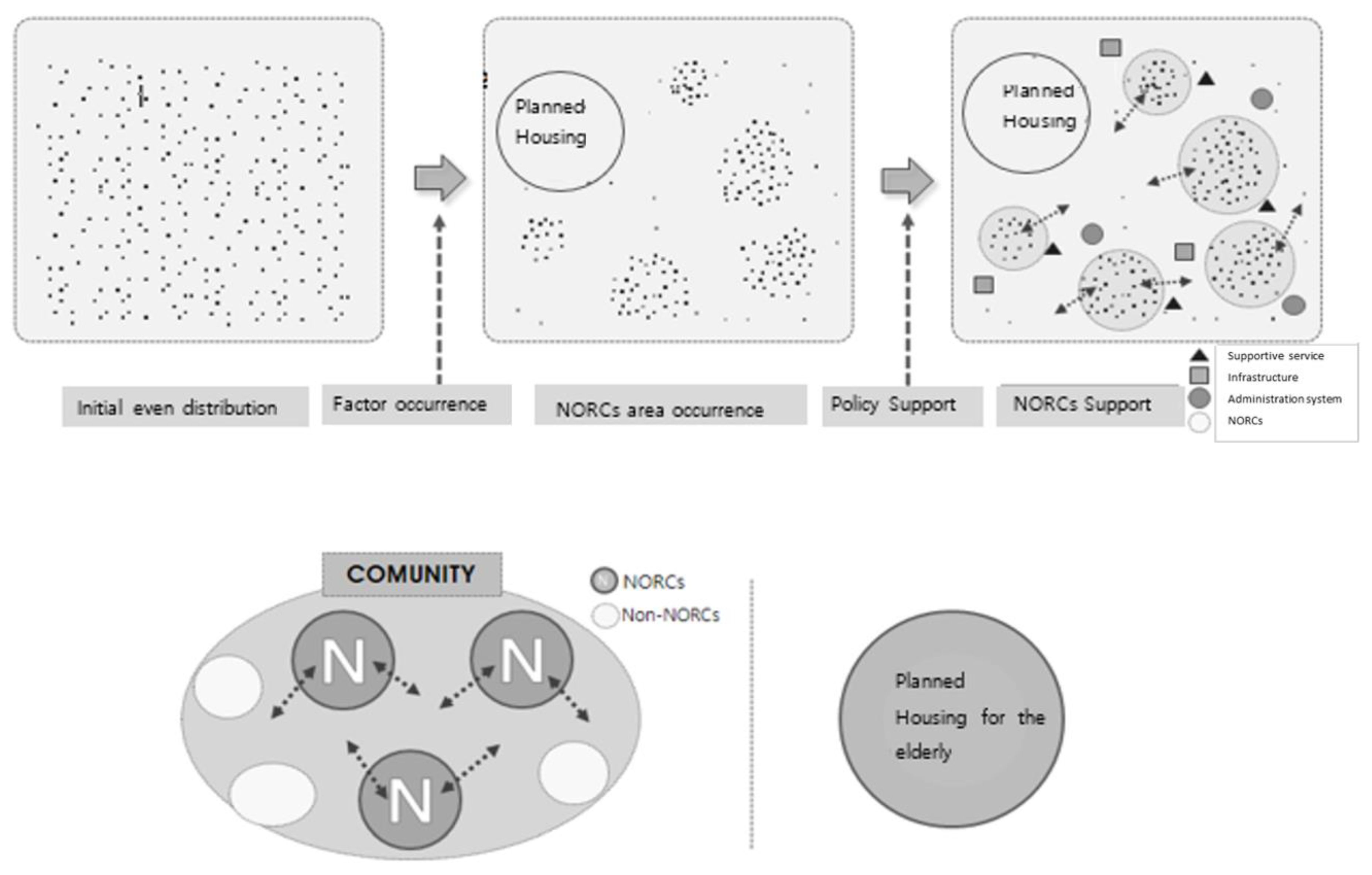

2. Literature Review on AIP and NORC

2.1. Factors Affecting AIP

2.2. The Aging and NORC Phenomenon of Korean Apartments

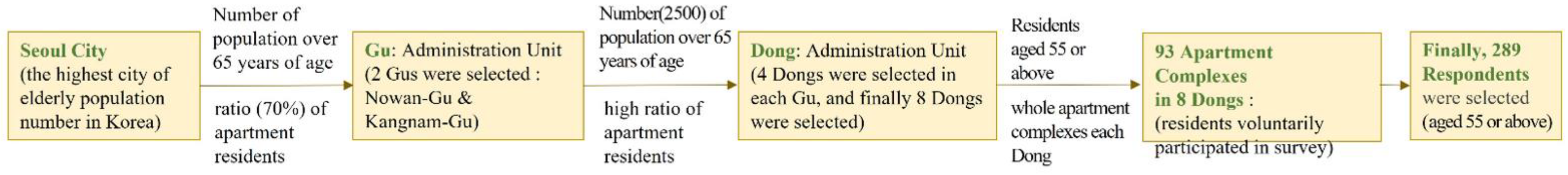

3. Method and Overview of Respondents

3.1. Data Sampling

3.2. Measures

3.3. Overview of the Respondents

4. Results

4.1. Results from Purpose 1: Willingness to Age in Place and Reasons for This

4.2. Results from Purpose 2: Relationship between Housing Attributes and Willingness to Age in Place

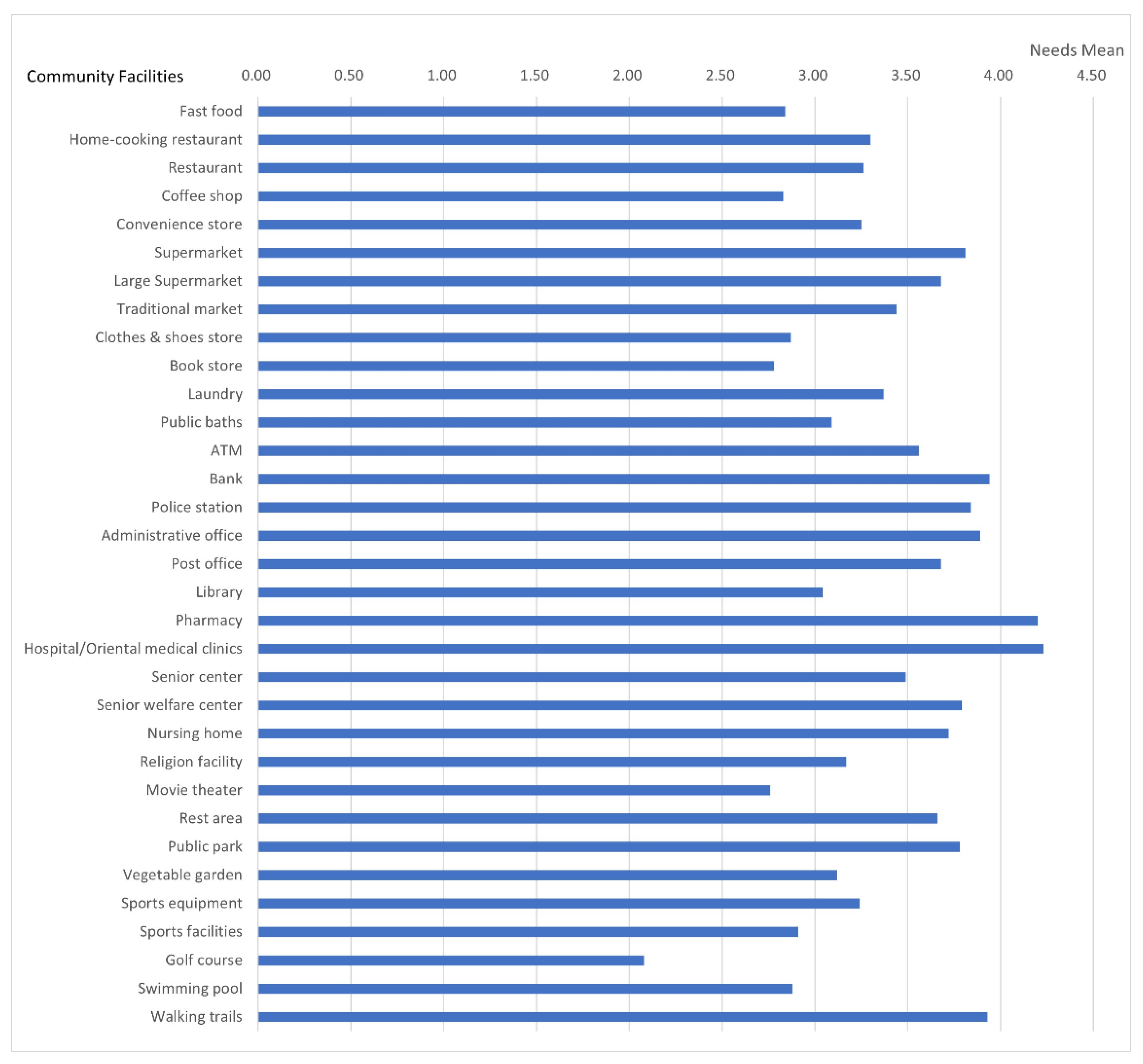

4.3. Results from Purpose 3: Relationship between Community Facilities and Willingness to Age in Place

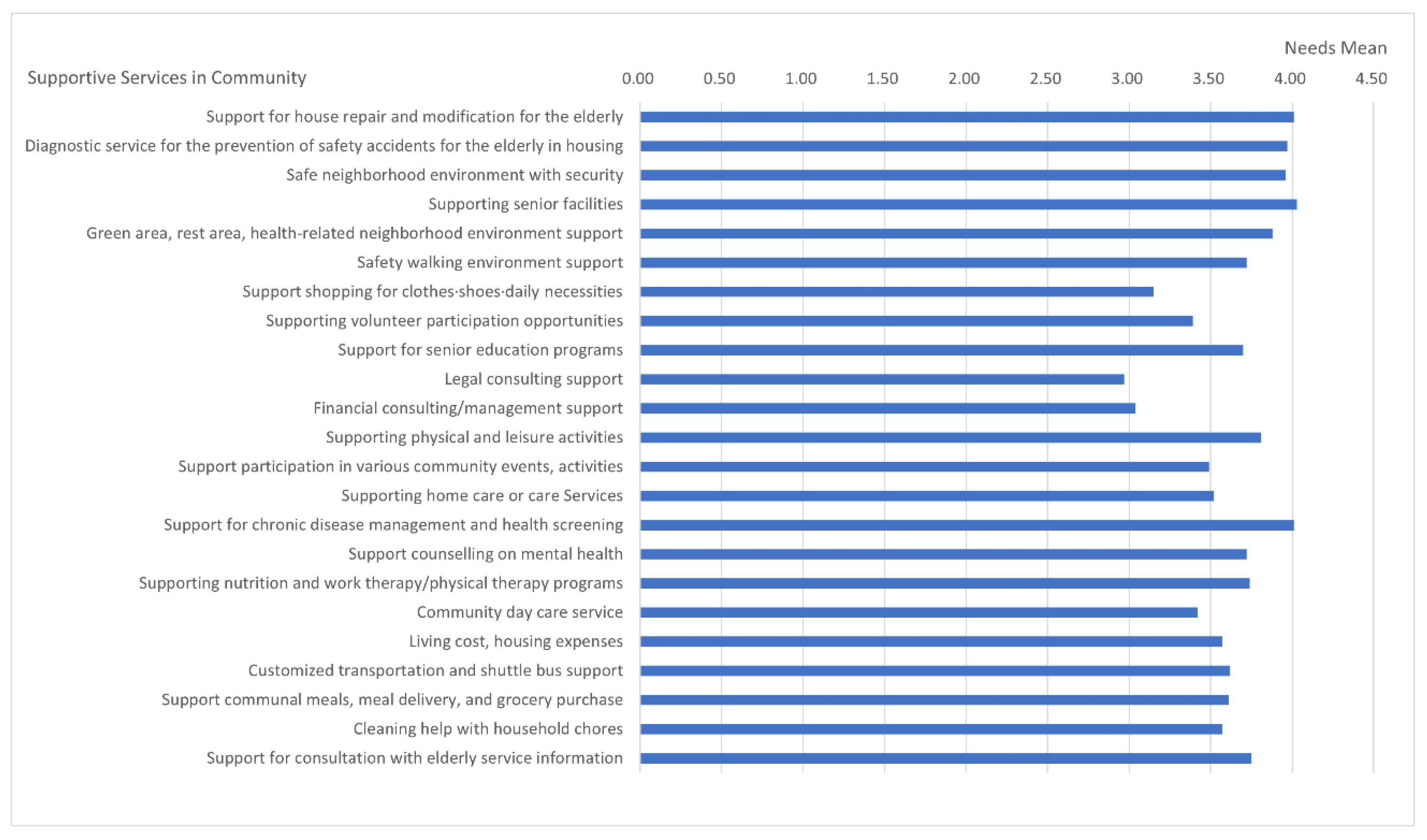

4.4. Results from Purpose 4: Relationship between Services and Willingness to Age in Place

4.5. Results from Purpose 5: Factors Affecting Willingness to Age in Place

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lawton, M.P. Competence, environmental press, and the adaptation of older people. In Aging and the Environment: Theoretical Approaches; Windley, P.G., Byerts, T.O., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wiles, J.L.; Leibing, A.; Guberman, N.; Reeve, J.; Allen, R.E.S. The meaning of “Aging in Place” to Older People. Gerontologist 2011, 52, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Active Ageing: A Policy Framework, Noncommunicable Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. Available online: https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/WHO-Active-Ageing-Framework.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Decade of Healthy Ageing 2020–2030, Ageing and Life Course. Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/decade-of-health-ageing/decade-healthy-ageing-update-march-2019.pdf?sfvrsn=5a6d0e5c_2 (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Jonson-Carroll, K. Factots that influence pre-retiree’s propensity to move at retirement. J. Hous. Elder. 1995, 11, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulliner, E.; Riley, M.; Maliene, V. Older people’s preferences for housing and environment characteristics. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, L.; Werner, C. Residential satisfaction among aging people living in place. J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, I.; Chen, J.; Zhu, B.; Xiong, L. Assessment of and improvement strategies for the housing of healthy elderly: Improving quality of life. Sustainability 2018, 10, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahn, M.; Kang, J.; Kwon, H. The concept of aging in place as intention. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y. Understanding aging in place: Home and community features, perceived age-friendiness of community, and intention toward aging in place. Gerontologist 2021, gnab070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M.; Kwon, H.; Kang, J. Supporting Aging-in-Place Well: Findings From a Cluster Analysis of the Reasons for Aging-in-Place and Perceptions of Well-Being. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2020, 39, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Gou, Z.; Jiang, B.; Qi, Y. Planning walkable neighborhoods for “aging in place”: Lessons from five aging-friendly districts in Singapore. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, D.; Chan, A. Diverse contributions of multiple mediators to the impact of perceived neighborhood environment on the overall quality of life of community-dwelling seniors: A cross-sectional study in nanjing. Habitat Int. 2020, 104, 102253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chippendale, T. Outdoor falls prevention strategy use and neighborhood walk ability among naturally occurring retirement community resident. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, E. Support from neighbors and aging in place: Can NORC programs make a difference? Gerontologist 2016, 56, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Park, J. Characteristics of the physical housing environments of the potential naturally occurring retirement communities: Focused on condominium apartment house in nowon-gu and gangnam-gu, seoul. J. Korean Hous. Assoc. 2017, 28, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.; Lee, Y.; Ha, H.; Kim, J.; Yeom, H. Reasons for seniors’ aging in place within their community. Fam. Environ. Res. 2014, 52, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hwang, E.; Brossoie, N.; Jeong, J.; Kim, I. The impacts of the neighborhood built environment on social capital for middle-aged and elderly korean. Sustainability 2021, 13, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M. Housing and Living Environment for Older People. In Handbook of Aging and the Social Science, 2nd ed.; van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Pastalan, L.A. Designing a Human Environment for the Frail Elderly. J. Archit. Educ. 1990, 31, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manion, P.; Rantz, M. Relocation stress syndrome: A comprehensive plan for long-term care admissions: The relocation stress syndrome diagnosis helps nurses identify patients at risk. Geriatr. Nurs. 1995, 16, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottoni, C.A.; Sims-Gould, J.; Winters, M.; Heijnen, M.; McKay, H.A. “Benches become like porches”: Built and social environment influences on older adults’ experiences of mobility and well-being. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 169, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebing, A.; Guberman, N.; Wiles, J. Liminal homes: Older people, loss of capacities, and the present future of living spaces. J. Aging Stud. 2016, 37, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Portero, C.; Alarcón, D.; Padura, Á.B. Dwelling conditions and life satisfaction of older people through residential satisfaction. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 49, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S. Housing management behavior of the elderly: Focus on the causal effects of housing satisfaction and housing selections. J. Korean Fam. Resour. Manag. 2001, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, I. A study on the factors affecting decisions by the super-aged on their preference of living with their children and continuously living in their current houses. J. Korean Hous. Assoc. 2011, 2, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonyea, J.G. Housing, health and quality of life. In The Handbook of Aging in Social Work; Berkman, B., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 559–567. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Moon, K.; Oh, C. Searching for policy orientation by the analysis of factors affecting aging in place in the aging community. J. Reg. Stud. 2015, 23, 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Lehning, A. City governments and aging in place: Community design, transportation and housing innovation adoption. Gerontologist 2001, 52, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Jang, S.; Oh, C.; Choi, S. Developing indicators for building elder-friendly communities in Korea. J. Korean Gerontol. Soc. 2014, 34, 55–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. A study on residential remodeling and needs of elderly households to activate “aging in place”. J. Hum. Ecol. 2006, 23, 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fernasdez, G. Component of the residential environment and socio-demographic characteristics of elderly. J. Hous. Elder. 2004, 13, 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, E.B.; Gottschalk, G. What makes older people consider moving house and what makes them move? Hous. Theory Soc. 2006, 23, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.; Abramsson, M.; Malmberg, B. Patterns of changing residential preferences during late adulthood. Ageing Soc. 2019, 39, 1752–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abramsson, M.; Andersson, E. Changing Preferences with Ageing—Housing Choices and Housing Plans of Older People. Hous. Theory Soc. 2016, 33, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Jong, P.; Rouwendal, J.; Hattum, P.; Brouwer, A. Housing Preferences of an Ageing Population: Investigation in the Diversity Among Dutch Older Adults. SSRN Electron. J. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.; Kenny, L.; Day, M.R.; O’Connell, C.; Finnerty, J.; Timmons, S. Exploring the housing needs of older people in standard and sheltered social housing. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2017, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seo, Y. A Study of the Senior Serviced Housing for Aging in Place in the Context of Urban. Regeneration. Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul University, Seoul, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Weis, R.; Julianna, M.; Fahs, M. Promoting active urban aging: A measurement approach to neighborhood walk ability for older adult. Cities Environ. 2010, 3, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H. Reliability analysis on the assessment indicators for senior walking environment. J. KIEAE 2012, 12, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, R.; Ormerod, M.; Burton, E.; Mitchell, L.; Ward-Thompson, C. Increasing independence for older people through good street design. J. Integr. Care 2010, 18, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Xu, Y.; Dai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, B.; Yang, H. Analyze the Psychological Impact of COVID-19 among the Elderly Population in China and Make Corresponding Suggestions. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 289, 112983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, I.H.; Michael, Y.L.; Perdue, L. Neighborhood Environment in Studies of Health of Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 37, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stuck, A.E.; Walthert, J.M.; Nikolaus, T.; Büla, J.; Hohmann, C.; Beck, J.C. Risk Factors for Functional Status Decline in Community- Living Elderly People: A Systematic Literature Review. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 48, 445–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holle, V.; Cauwenberg, J.; Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Deforche, B.; Weghe, N.; Dyck, D. Interactions Between Neighborhood Social Environment and Walkability to Explain Belgian Older Adults’ Physical Activity and Sedentary Time. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McDonough, K.; Davit, J. It takes a village: Community practice, social work and aging-in-place. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work. 2001, 54, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonad, E. Moving to and living in a retirement home: Focusing on elderly people’s sense of safety and security. J. Hous. Elder. 2006, 20, 5–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncombe, W.; Robbins, M.; Wolf, D.A. Place characteristics and residential location choice among the retirement-age population. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2003, 58, S244–S252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaye, H.; Mitchel, P.; Charlene, H. Do noninstitutional long-term care service reduce medical spending? Health Aff. 2009, 28, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, P. Naturally Occurring Retirement Community (NORC) Services Program, Livable New York Resource Manual. 2012. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/24212816/Livable_New_York_Resource_Manual (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Greenfield, E.A.; Scharlach, A.E.; Lehning, A.J.; Davitt, J.K.; Graham, C.L. A tale of two community initiatives for promoting aging in place: Similarities and differences in the national implementation of NORC programs and villages. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bedney, B.J.; Goldberg, R.B.; Josephson, K. Aging in place in naturally occurring retirement communities: Transforming aging through supportive service programs. J. Hous. Elder. 2010, 24, 304–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladeck, F. A Good Place to Grow Old: New York’s Model for NORC Supportive Service Programs; United Hospital Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Korea. 2017–2067 Special Estimate of Future Population; Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Korea, 2019.

- United Nations. World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision; Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- Hunt, M.; Gunter-Hunt, G. Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities. J. Hous. Elder. 1985, 3, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Park, J.; Lee, H. The Development of a measurement method for place attachment and its verification with a housing satisfaction measure: A survey of university students about their homes. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2016, 15, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fornara, F.; Bonaiuto, M.; Bonnes, M. Cross-Validation of Abbreviated Perceived Residential Environment Quality (PREQ) and Neighborhood Attachment (NA) Indicators. Environ. Behav. 2010, 42, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenk, D.; Kuwahara, K.; Zablotsky, D. Older Women’s Attachments to Their Home and Possessions. J. Aging Stud. 2004, 18, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.H. A study on the leisure activity and using behavior of neighborhood facilities for the aged. J. Korean Hous. Assoc. 1997, 8, 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.J.; Lee, S.Y. Study on the consciousness of community facilities for the elderly. J. Archit. Inst. Korea 2008, 24, 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, M.P. Planning and Managing Housing for the Elderly; John Wiley and Sons: Norman, OK, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Y.S. Location of elderly housing and neighborhood. Architecture 2003, 47, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka, M. Ways to make people active: The role of place attachment, cultural capital, and neighborhood ties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Related Elements | Literature Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Personal | Gender, marital status, education level, income, social activity level | [25,48] |

| Religion, number of family members | [26] | |

| House/Housing | Convenience of housing structure: interior space inside a house | [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37] |

| Home ownership status | [26,28] | |

| Period of residence in the current home | [26] | |

| Housing type | [25] | |

| Housing satisfaction | [25] | |

| Ecologically friendly features: ventilation and air quality | [8] | |

| Community | Convenient living conditions and accessibility of the neighborhood facilities | [6,17,32,36] |

| Pedestrian environment, convenience and safety of transportation and utilization facilities | [6,12,28,29,38,39,40,41] | |

| Regional senior citizens’ facilities | [38] | |

| Location of a house | [28,34,35,36,38] | |

| Safe neighbors | [6] | |

| Well-organized and environmentally friendly buildings | [12,14,41,42,43,44,45] | |

| Service factors | Community care service | [49] |

| Various services such as health care and care | [28,46] | |

| Home improvement, housing repair services | [31,46,47] |

| Category | Apartment (9 Complexes) | Condominium Apartment (84 Complexes) | Total (93 Complexes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years of building | 22.67 | 26.01 | 25.14 |

| Ratio of over 55s | 48.74% | 27.09% | 29.18% |

| Number persons over 55 | 1750.11 | 1141.57 | 1200.22 |

| Category | Levels | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (n = 289) | Male | 70 (24.2) |

| Female | 210 (75.8) | |

| Job (n = 266) | Employed | 60 (22.6) |

| Unemployed | 206 (77.4) | |

| Education (n = 288) | Elementary school graduate | 42 (14.6) |

| Middle school graduate | 32 (11.1) | |

| High school graduate | 94 (32.6) | |

| College graduate or higher | 120 (41.7) | |

| Family types (n = 289) | Couple | 105 (36.3) |

| Single | 69 (23.9) | |

| Couple + blended family | 100 (34.6) | |

| Single + blended family | 15 (5.2) | |

| Monthly income (n = 277) | ≤1,000,000 KRW | 75 (27.1) |

| 1,000,000 < income ≤ 3,000,000 KRW | 107 (38.6) | |

| 3,000,000 < income ≤ 5,000,000 KRW | 59 (21.3) | |

| 5,000,000 < income ≤ 7,000,000 KRW | 21 (7.6) | |

| 7,000,000 KRW < | 15 (5.4) | |

| Ownership (n = 283) | Owned house | 225 (79.5) |

| Rent house | 58 (20.5) | |

| Subjective health condition (n = 266) | Very healthy | 31 (11.7) |

| Health | 108 (40.6) | |

| Normal | 100 (37.6) | |

| Weak | 25 (9.4) | |

| Very weak | 2 (0.8) |

| Willingness to Age in Place | Questionnaire Measuring Items | n | Mean (Std) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preference | I want to live in this house until I die. | 279 | 3.51 (1.388) |

| I want to live in or near this neighborhood until I die. | 280 | 3.66 (1.243) | |

| Feeling | I’ll miss home very much when I leave my current home. | 284 | 3.96 (1.104) |

| It will be very difficult for me to leave my neighborhood or nearby area. | 284 | 3.49 (1.245) | |

| Total | 270 | 3.61 (1.046) |

| Contents | Mean (Std) |

|---|---|

| Relationship | |

| It’s because my family is close to me. | 3.14 (1.410) |

| I have a friend in this neighborhood. | 3.41 (1.356) |

| It is because there are many neighbors, such as senior citizen centers and social gatherings. | 3.23 (1.382) |

| Neighborhood environment | |

| There is someone that can help professionally in this neighborhood. | 3.11 (1.383) |

| There is a religious facility I go to in this neighborhood. | 2.85 (1.417) |

| The surrounding amenities are good. | 3.65 (1.189) |

| The surrounding natural environment is good. | 3.62 (1.223) |

| Home/House environment | |

| I just like this house. | 3.43 (1.227) |

| I like this house more than anywhere else. | 3.73 (1.147) |

| This house is very meaningful to me. | 3.87(1.160) |

| It is because I’m happy to be in this house. | 3.93(0.990) |

| House Ownership | Owned (n = 215) | Rent (n = 55) | t-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (Std) | 3.70(0.42) | 3.37(0.52) | t = 2.085 * |

| Housing /Resident Attributes | Willingness to Age in Place |

|---|---|

| Living period in current house | Pearson’s r = 0.368 ** |

| Living period in current neighborhood | Pearson’s r = 0.327 ** |

| Age of residents | Pearson’s r = 0.270 ** |

| Factors | Communities | Needs Mean (Std) | Pearson’s r |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meal | Fast food | 2.84 (1.397) | 0.116 |

| Home-cooking restaurant | 3.30 (1.340) | 0.193 ** | |

| Restaurant | 3.26 (1.331) | 0.138 * | |

| Coffee shop | 2.83 (1.380) | −0.014 | |

| Purchasing | Convenience store | 3.25 (1.379) | 0.092 |

| Supermarket | 3.81 (1.283) | 0.173 ** | |

| Large supermarket | 3.68 (1.356) | 0.169 ** | |

| Traditional market | 3.44 (1.402) | 0.119 | |

| Clothes and shoes store | 2.87 (1.297) | 0.121 * | |

| Book store | 2.78 (1.400) | −0.021 | |

| Amenity | Laundry | 3.37 (1.387) | 0.073 |

| Public baths | 3.09 (1.365) | 0.122 * | |

| ATM | 3.56 (1.369) | 0.039 | |

| Bank | 3.94 (1.224) | 0.155 * | |

| Public | Police station | 3.84 (1.297) | 0.185 ** |

| Administrative office | 3.89 (1.219) | 0.171 ** | |

| Post office | 3.68 (1.297) | 0.135 * | |

| Library | 3.04 (1.487) | −0.007 | |

| Medical | Pharmacy | 4.20 (1.173) | 0.186 ** |

| Hospital/Oriental medical clinics | 4.23 (1.144) | 0.205 ** | |

| Elderly-related | Senior center | 3.49 (1.434) | 0.220 ** |

| Senior welfare center | 3.79 (1.329) | 0.351 ** | |

| Nursing home | 3.72 (1.283) | 0.353 ** | |

| Leisure & religion | Religion facility | 3.17 (1.427) | 0.134 * |

| Movie theater | 2.76 (1.423) | −0.078 | |

| Rest area | 3.66 (1.330) | 0.150 * | |

| Public park | 3.78 (1.359) | 0.108 | |

| Vegetable garden | 3.12 (1.416) | 0.045 | |

| Health | Sports equipment | 3.24 (1.413) | 0.056 |

| Sports facilities | 2.91 (1.434) | 0.019 | |

| Golf course | 2.08 (1.323) | −0.073 | |

| Swimming pool | 2.88 (1.399) | 0.052 | |

| Walking trails | 3.93 (1.287) | 0.090 |

| Needs for Services | Mean (Std) | Pearson’s r |

|---|---|---|

| Support for consultation with service information for the elderly | 3.75 (1.205) | 0.186 ** |

| Cleaning help with household chores | 3.57 (1.262) | 0.185 ** |

| Support for communal meals, meal delivery, and grocery purchase | 3.61 (1.167) | 0.177 ** |

| Support for shopping for clothes, shoes, and daily necessities | 3.15 (1.321) | 0.160 ** |

| Customized transportation and shuttle bus support | 3.62 (1.223) | 0.218 ** |

| Living cost, housing expenses | 3.57 (1.316) | 0.184 ** |

| Community day care service | 3.42 (1.311) | 0.126 * |

| Supporting nutrition and work therapy/physical therapy programs | 3.74 (1.202) | 0.262 ** |

| Support for counselling on mental health | 3.72 (1.212) | 0.197 * |

| Support for chronic disease management and health screening | 4.01 (1.063) | 0.285 ** |

| Supporting home care or care services | 3.52 (1.382) | 0.166 ** |

| Support for participation in various community events and activities | 3.49 (1.237) | 0.165 ** |

| Supporting physical and leisure activities | 3.81 (1.154) | 0.200 ** |

| Financial consulting/management support | 3.04 (1.345) | −0.028 |

| Legal consulting support | 2.97 (1.343) | 0.025 |

| Support for senior education programs | 3.70 (1.218) | 0.244 ** |

| Supporting volunteer participation opportunities | 3.39 (1.268) | 0.260 |

| Safe walking environment support | 3.72 (1.188) | 0.215 ** |

| Green areas, rest areas, health-related neighborhood environment support | 3.88 (1.166) | 0.186 ** |

| Supporting senior facilities | 4.03 (1.014) | 0.269 ** |

| Safe neighborhood environment with security | 3.96 (1.066) | 0.283 ** |

| Diagnostic service for the prevention of safety accidents for the elderly in housing | 3.97 (1.052) | 0.260 ** |

| Support for house repair and modification for the elderly | 4.01 (1.088) | 0.216 ** |

| Factors | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community Facilities Needs | Medical | Public and Elderly Related | Restaurant and Purchases |

| Home-cooking restaurant | 0.155 | 0.216 | 0.639 |

| Restaurant | 0.144 | 0.121 | 0.834 |

| Supermarket | 0.595 | 0.186 | 0.514 |

| Large supermarket | 0.342 | 0.094 | 0.725 |

| Clothes and shoes store | 0.034 | 0.577 | 0.602 |

| Senior center | 0.353 | 0.781 | 0.139 |

| Senior welfare center | 0.495 | 0.633 | 0.104 |

| Nursing home | 0.411 | 0.627 | 0.066 |

| Police office | 0.569 | 0.593 | 0.245 |

| Community center | 0.620 | 0.565 | 0.238 |

| Post office | 0.487 | 0.543 | 0.416 |

| Pharmacy | 0.859 | 0.314 | 0.176 |

| Hospital/Oriental medical clinics | 0.860 | 0.297 | 0.195 |

| Bank | 0.790 | 0.212 | 0.300 |

| Religion facilities | 0.224 | 0.438 | 0.443 |

| Baths | 0.093 | 0.726 | 0.374 |

| Rest area | 0.351 | 0.512 | 0.464 |

| Factor Items of Services Need | Factor1 Health and Daily Living Support Services | Factor2 Housing Services | Factor3 Activities and Education Support Services |

|---|---|---|---|

| Support for consultation with service information for the elderly | 0.549 | 0.195 | 0.347 |

| Cleaning help with household chores | 0.790 | 0.186 | 0.188 |

| Communal meals, meal delivery, and grocery purchase support | 0.807 | 0.303 | 0.113 |

| Customized transportation and shuttle bus support | 0.761 | 0.234 | 0.202 |

| Living cost, housing cost | 0.611 | 0.430 | 0.012 |

| Community day care services | 0.690 | 0.168 | 0.419 |

| Supporting nutrition and work therapy/physical therapy programs | 0.641 | 0.356 | 0.399 |

| Support for counselling on mental health | 0.561 | 0.323 | 0.408 |

| Support for chronic disease management and medical examination | 0.545 | 0.483 | 0.365 |

| Supporting home care or care services | 0.698 | 0.070 | 0.407 |

| Support for participation in various community events and activities | 0.291 | 0.172 | 0.806 |

| Supporting physical and leisure activities | 0.201 | 0.283 | 0.788 |

| Support for senior education programs | 0.335 | 0.209 | 0.685 |

| Support for shopping for clothes, shoes, and daily necessities | 0.381 | 0.279 | 0.507 |

| Safe walking environment support | 0.202 | 0.603 | 0.545 |

| Green area, rest, health-related neighborhood environment support | 0.090 | 0.624 | 0.533 |

| Supporting senior facilities | 0.320 | 0.742 | 0.330 |

| Safe neighborhood environment for security | 0.227 | 0.791 | 0.348 |

| Diagnostic service for the prevention of safety accidents for the elderly in housing | 0.296 | 0.847 | 0.177 |

| Support for home repair and modification for the elderly | 0.301 | 0.785 | 0.190 |

| Model Summary | Statistics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | Std. Error of the Estimate | R2 Change | F Value | df1 | df2 | Sig. F |

| 1 | 0.356 a | 0.127 | 0.123 | 0.96498 | 0.127 | 34.631 | 1 | 238 | 0.0000 |

| 2 | 0.404 b | 0.163 | 0.156 | 0.94696 | 0.036 | 23.055 | 2 | 237 | 0.0000 |

| 3 | 0.433 c | 0.188 | 0.178 | 0.93467 | 0.025 | 18.201 | 3 | 236 | 0.0000 |

| 4 | 0.456 d | 0.208 | 0.194 | 0.92503 | 0.020 | 15.422 | 4 | 235 | 0.0000 |

| Model 4 a | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients β | t-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | |||

| (constant) | 2.887 | 0.130 | 22.201 *** | |

| Living period in house | 0.031 | 0.008 | 0.261 | 3.892 *** |

| Housing service | 0.188 | 0.059 | 0.186 | 3.192 ** |

| Living period in neighborhood | 0.016 | 0.006 | 0.181 | 2.705 ** |

| Support service for education and participation activities | 0.145 | 0.059 | 0.142 | 2.438 * |

| R = 0.456, R2 = 0.208, Adjusted R2 = 0.194. F-value = 15.422 ***, Durbin–Watson = 1.526. | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, J.-A.; Choi, B. Factors Affecting the Intention of Multi-Family House Residents to Age in Place in a Potential Naturally Occurring Retirement Community of Seoul in South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168922

Park J-A, Choi B. Factors Affecting the Intention of Multi-Family House Residents to Age in Place in a Potential Naturally Occurring Retirement Community of Seoul in South Korea. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):8922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168922

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Jung-A, and Byungsook Choi. 2021. "Factors Affecting the Intention of Multi-Family House Residents to Age in Place in a Potential Naturally Occurring Retirement Community of Seoul in South Korea" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 8922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168922

APA StylePark, J.-A., & Choi, B. (2021). Factors Affecting the Intention of Multi-Family House Residents to Age in Place in a Potential Naturally Occurring Retirement Community of Seoul in South Korea. Sustainability, 13(16), 8922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168922