1. Introduction

In 2015, an informal group within the OECD called the Working Party on SMEs and Entrepreneurs (WPSMEE) embarked on the task of identifying potential new sources for funding SMEs. The WPSMEE produced two documents: (1) the report “New Approaches to Economic Challenges” (NAEC), approved by the G20 finance ministers and Central Bank governors in February 2015; and (2) the document “G20/OECD High-Level Principles on SME Financing”, approved in November 2015 [

1]. These studies point out the limitations of a conventional bank loan as a financing instrument for SMEs in general, and for innovative enterprises, start-ups, and fast-growing companies in particular. Similarly, OECD reports from 2017 and 2020 underscore that these companies significantly foster economic growth and innovation, which is why addressing their financial needs is of crucial importance [

2,

3]. Moreover, this is the reason why we should still seek to broaden the range of financing instruments for innovative ventures, as the finance gap experienced by SMEs persists, in the spheres of both debt and equity [

4]. The OECD also emphasizes the ever-growing need to develop new instruments and markets, and the need to share experience and good practices in this area [

1]. The pool of alternative financing instruments includes crowdlending and equity crowdfunding (CF). The validity of crowdfunding as a key financing option is confirmed by the value of the acquired capital. CF projects raised a total of USD 17.2 billion in North America, USD 10.24 billion in Asia, and USD 6.48 billion in Europe. Data from the EU Startup Monitor of 2018 reveal that 18.1% of European start-ups finance their activity through crowdfunding, which places this instrument alongside operational cash flows (used by 15.7%) and government subsidies (20%) in terms of popularity [

5,

6]. The Statista forecasts [

7] indicate that transaction value will reach the compound annual growth rate (CAGR 2020–2024) of 5.8%, which will generate an estimated total amount of USD 180.5 million in 2024. In 2020, an average campaign in the sector of social funding will earn USD 5270 [

7]. All of these data point to further dynamic growth of this form of financing. It is no coincidence that in 2015 the Sustainable Development Goals were created, which were included in the United Nations Development Agenda 2030. Among the many goals of sustainable development are responsible consumption and production, as well as partnership for goals. Additionally, according to the concept of sustainable development in the Brundtland Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (un.org) [

8], one of the important elements of building sustainable development is connecting the environment and the economy in the decision-making process. At the same time, the UN Secretary General established the Task Force on Digital Financing of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as part of his broader Roadmap for Financing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: 2019–2021. In the final report, the group of experts indicated that one of the important forms of financing sustainable development goals is crowdfunding. Crowdfunding platforms have opened new avenues for aggregating atomized interests, enabling SMEs to overcome trust barriers and to act collectively in financing things they value [

9]. The innovation of CF lies in the fact that by using the latest IT technologies and CF platforms, entrepreneurs can obtain funds for financing activities and projects directly from the “crowd”. Bearing in mind the above, it is worth paying attention to the key elements of crowdfunding that distinguish it from other sources of financing. First, crowdfunding fills the funding gap at an early stage of development. Second, crowdfunding uses power of the Internet and social media. Third, it favours the testing and implementation of unique ideas among the public. Finally, it facilitates direct consumer involvement. As a result, in addition to the funds accumulated through CF, values of a different type are generated. In our opinion, it is necessary to identify those aspects of crowdfunding that can create significant value for SMEs. These can have an impact on the company’s development, including strategic financial decisions, and the willingness of companies to use CF as a means of obtaining financing.

In light of the hopes and recommendations for crowdfunding as an alternative financing option for start-ups and SMEs, it is becoming increasingly important to understand how its use affects the value of these enterprises, especially considering that in the literature review a gap was identified in such an approach. A better understanding of the shaping of corporate value through CF, including the impact of CF on financial value, may contribute to the sustainable development of companies. This paper presents an analysis of reward-based crowdfunding, equity crowdfunding, and crowdlending as business models oriented towards marketing and product commercialisation [

10]; it aims to indicate to what extent these CF models generate added value for companies. In other words, we ask about the appeal of this financing option for an entrepreneur interested in the context of value-based management and sustainability. The added value of our undertaking is the holistic perspective of the impact of crowdfunding on company value, as well as the selected point of view (of the entrepreneur/owner). Both result from our novel approach to extant research and analyses on the topic.

In terms of structure, the paper begins with an outline of the methodology employed in our study. Then, it presents a literature review around the theme of value in CF, to finally discuss the findings of our analyses, which we based on value-based management and custom models used for examining the value of crowdfunding for SMEs.

2. Methodology

According to the theory of value-based management, every business aims to maximise value for its owners [

11,

12]. Value is created in the sphere of macroeconomic and microeconomic factors alike [

11]. The macroeconomic sphere, tied to the operational and financial factors, impacts the value of free cash flows. VBM asserts that every feature/process/activity that contributes to increasing cash flows is profitable for the company, as it drives company value. Conversely, every feature/process/activity that contributes to decreasing cash flows degrades company value. Due to the nature of the relationships between participants in crowdfunding, not only financial (quantitative) aspects, but also non-financial aspects, are important; therefore, a qualitative analysis was used to identify and categorize created values and determine the relationship between them. Qualitative analysis allows for a better understanding of these relationships. Since we define CF as an ecosystem, we wish to determine how the interactions occurring within its bounds impact its originator—the start-up and/or SME in question. Our analyses aim to provide answers to the following questions:

Are all participants in the CF ecosystem involved in the co-creation of value?

Does CF contribute to creating new value in all of the perspectives: of learning, the customer, internal processes (operations), and finance (does it impact the value of future cash flows?)?

Does the use of CF drive company value?

To answer these questions we take the following steps:

Literature review;

Analysis of the crowdfunding ecosystem and co-created values;

Norton–Kaplan map and values co-created in CF (customer, internal, and learning perspectives);

Influence of co-created values on EVA (financial perspective).

We started our research with a literature review of value creation through CF, as follows:

We reviewed the literature for CF-related topics using the keywords “crowdfund *”, “value”, “added value”, and “value co-creation” in peer-reviewed scientific articles, (* allows to find keywords with different endings);

We narrowed our research to the words “Norton Kaplan” and “EVA”;

Duplicate articles were discarded;

We examined summaries of articles by the most cited authors who referred to value in crowdfunding;

A content analysis was carried out for all articles that we refer to directly in the article.

Then, to answer questions about the impact of CF on company value, we employ the method of deduction—that is, a line of reasoning from a sentence or sentences that we deem true to reach logical conclusions. Deductive reasoning explains a phenomenon by showing that it may be extrapolated from a general rule [

13]. In this case, we extrapolate from the value constellation theory and the strategy map idea developed by Norton and Kaplan. To quote the authors: “The corporate scorecard and map identify and measure the sources of corporate value creation at each of four levels or ‘perspectives’ financial, customers, process and learning and growth” [

14]. The theory of value constellation is helpful in addressing questions 1 and 2, as it allows to identify the value created in the CF ecosystem, and then to analyse from the entrepreneurial perspective the interplay between the created values and the perspectives included in the Norton–Kaplan model [

15]. Value can be measured in different ways, depending on its type. From a financial point of view, profit, cash flow, or dividends can be used to measure value. However, because of the holistic approach and multifaceted nature of value creation in CF, the best measure is EVA, because it takes into account both financial and non-financial aspects affecting the value of the enterprise. This methodology was previously used to analyse the impact of various business activities on economic value added [

16,

17,

18]. Upon the identification of CF-related factors affecting value growth and degradation, we conclude whether this financing option may indeed impact the value growth of a company and sustainable development of the enterprise [

19].

3. Literature Review

The literature review completed across databases such as WoS, Scopus, ProQuest, and Science Direct reveals that the issue of value in crowdfunding (CF) is studied from a range of angles. Looking for a definition of crowdfunding, we performed a simple analysis of the Web of Science database for the years 2011–2021. We indicated crowdfunding as a keyword, which extracted 2132 articles and 21,556 total citations. The most cited authors were Mollick [

20] (1156 citations), Belleflame et al. [

21] (739 citations), and Ahlers et al. [

22] (479 citations). Each of the authors mentioned focused on different elements and different models of crowdfunding in their definition of crowdfunding. Ahlers et al. [

22] define only equity crowdfunding, Belleflame et al. [

21] focus on the role of the internet and access to a wide range of potential donors in donation crowdfunding, while Mollick [

20] emphasizes the non-financial factors important in crowdfunding, and the lack of standard financial intermediaries that applies to reward crowdfunding. However, it is worth noting that the indicated articles cover the early period of development of crowdfunding, while among the articles most cited in the last 5 years (with the keyword being the definition of crowdfunding) is one by Hossain and Oparaocha from 2017 [

23] (14 citations WoS database); the authors conducted an extensive analysis of the concept itself—the phenomenon of crowdfunding—as well as the motivations behind it, concluding the need for further studies in this area.

In our opinion, an interesting definition analysis was presented by Liang et al. [

24], distinguishing three research areas: The first area highlights the purpose of previous—mainly qualitative—research, where the definition, business model, risk, and legal aspects of crowdfunding were identified. The second area covers research on the motivation of fundraisers and investors to participate in crowdfunding activities. Finally, the third area includes a group of studies on the antecedents of crowdfunding success.

It is worth noting, however, that if even some of the publications we analysed included a research area devoted to the added value of crowdfunding for SMEs, we did not find publications in which the Norton–Kaplan value map or EVA were used for the value analysis of CF. In crowdfunding-related research, the notion of value appears chiefly in the following contexts:

Value of the CF market and CF transactions; market growth dynamics [

25,

26,

27];

The identification of stakeholder groups and the analysis of their mutual connections, considering aspects such as information flow and created value [

20,

21,

24,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34];

A focus on customer value and/or investor value in CF, and project success factors [

28,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40];

Crowdfunding platforms (CFPs) and their role, importance, and added value for project participants [

41,

42,

43,

44].

Examples of research themes related to value in crowdfunding are included in

Table 1.

It should be noted that the existing analyses tend to focus on a selected CF agent or the processes driving the relations between selected stakeholder groups, rather than on the sources of value presented by CF as an ecosystem for the SMEs. The most focused-on forms of value co-creation in CF are presented in

Table 2.

To begin with, the authors frame CF as a service ecosystem, which illustrates perfectly the interplay between participants, as well as the aspects relevant to value creation within the CF ecosystem [

46,

47,

48]. Cucari and Nuhu [

47] discuss the conversion of value into economic value in CF. However, like Quero and Ventura [

46,

47,

48], they fail to attribute greater importance to the financial aspect. Schmitt and Petroll [

53] analyse value co-creation from the point of view of crowdfunding platforms, and focus on non-financial value. The authors pay a lot of attention to the co-creation of the value of the offered projects and the behaviour of backers as part of mutual interactions with entrepreneurs. Each of these analyses brings a lot of important information about investors’ behaviour, their motivations, and he role and importance of crowdfunding platforms from the point of view of co-created values [

45,

49,

50,

51,

52]. These analyses combine the co-creation value theory with other theories and models in various ways, as in the article by Gangi and Daniele [

49], where the axioms of co-production and use-value were applied. Usually, in these analyses, the entrepreneur is assessed from the point of view of the offered project, and as a participant in a crowdfunding campaign. These studies lack the perspective of the SMEs, where decisions are made by the owner. Thus, the presented results become the basis for undertaking research that takes into account the entrepreneur’s perspective.

It is not enough to observe that CF as a financing option may be categorized as a financial service [

46,

47]. An in-depth analysis exploring the impact of CF on company value from the entrepreneurial standpoint is of critical importance for both the growth of CF itself and the advancement of innovation within the company. This mindset has informed the analyses presented later in the paper.

4. Findings

The concept of crowdfunding reveals three groups of participants: entrepreneurs, crowdfunders (investors/backers), and mediators (crowdfunding platforms (CFPs)). Characteristically, CF is readily accessible to both capital providers and entrepreneurs. The CFPs play a unique role in the system, ensuring not only resource acquisition, but also information exchange between entrepreneurs and investors. CF works on the basis of the mutual relations and interactions between both groups of agents involved. It is used to fund projects planned from start to finish, or for experimental interdisciplinary ventures where the final outcome is marked with a degree of uncertainty. The projects are designed in line with the guiding principle of win more–win more [

16,

17,

18]. In the light of the above, CF may be defined as an ecosystem [

19] relying on the following array of interactions:

Presentation of the idea or concept on a CFP;

Exchange of information and communication between the “crowd” and the “crowdfunders” through the platform;

The crowdfunders’ decision to pledge funds;

Rewards for the crowdfunders.

In principle, crowdfunding projects follow four basic business models [

23]:

Donation-based crowdfunding—which involves fundraising for philanthropic purposes, health-related projects, artistic endeavours, or research. The backers expect no pecuniary gain for their support;

Reward-based crowdfunding—which involves the co-financing of various projects in exchange for tangible or non-tangible rewards, such as T-shirts, or having the name of the backer posted on the campaign website. Reward-based crowdfunding may take the form of pre-purchase CF, where the backers buy the product at the development stage. Thus, the financing involves an exchange between the enterprise and the backers;

Equity crowdfunding—which involves stock investments. The capital is provided by investors looking to profit from their share in future cash flows. This model does not rely on consuming the company’s product as a reward for the invested capital;

Crowdlending—a lending-based type of crowdfunding where the investors, referred to as lenders, gain profit in the form of interest on the loans granted.

The review of CF models reveals that an enterprise that opts for this form of financing needs—apart from an interesting project—a good grasp of its operational capacities, external circumstances, the needs of clients, crowdfunding itself and its costs, and the operation of CFPs. While the backers of donation-based crowdfunding campaigns expect no tangible gain, and content themselves with the satisfaction that comes with helping others (utilitarian, intangible values), other business models involve an exchange of values that may be intangible (knowledge), tangible (services, products), or purely financial (interest). Therefore, the entrepreneur should make their decision by weighing up potential profits and costs relevant to their individual situation. The final argument that should tip the balance in favour of crowdfunding is not only the advantage of expected profits over costs. For an entrepreneur, the added value of crowdfunding may not only be financial, but also social.

4.1. Crowdfunding—A Constellation of Values

Adopting the definition of crowdfunding as an ecosystem seems to be advisable, because it takes into account all of its important features and elements; however, such an approach does not allow the use of the value chain method in the analysis of the created/co-created value. This is because value chain presupposes the sequential nature of value creation [

54,

55]. Meanwhile, in the CF ecosystem, the relationships between individual components are more complex. Therefore, it is preferable to use the value constellation theory, which entertains various means of coordination, types of integration [

46,

47,

48], and mutual adaptations observed within the ecosystem. According to the value constellation theory, an enterprise establishing connections with other entities creates a constellation of agents, and their cooperation leads to the creation (co-creation) of value. Quero, Ventura, and Kelleher [

46] performed an analysis of CF value at three levels—micro-context, meso-context, and macro-context—allowing them to trace mutual connections between agents and co-creation of values, but overlooking the owner’s perspective. The model we propose complements existing research into value creation through CF, but references the co-created values against those of critical importance for SME owners. Drawing upon the ecosystem model, we distinguish the following groups of agents: an SME, a CF platform (CFP), the crowd (CD), crowdfunders (CFs), clients (CS), and their mutual connections. Interactions between the agents are defined on the basis of the value constellation theory, as presented in

Figure 1.

As we can see in

Figure 1, no link is unidirectional. Even if we can divide the processes into individual stages, as illustrated by numbers 1–6, each interaction prompts a response. In the figure, solid lines represent an interaction involving the transfer of funds and the delivery of a product or a crowd transfer. We can see the connections made through actions taken on the CFP: (1) SME—CFP: a new product idea presented on the CFP (information flow) and exchange of information through CFP and crowd line; (2) CD—CFP and (3) CD—CFs: a group of investors emerges from the crowd; and finally, resource acquisition (6. CFs—CFP—SME). Dotted lines that link SME with CFP and the CD present the communication and information exchange alone. Solid lines (6) CFs—CFP—SME present exchange money, rewards, and payments between investors and SMEs. Processes do not necessarily lead to investor acquisition but, if the project is a success, they may provide a new group of clients who do not invest in the project but simply want to buy products, which is depicted as solid line (5) CD–CS: emergence of client groups and future investors eventually (line 4). The CF ecosystem is heavily influenced (7—dotted lines) by legal regulations established by the government (GMT). For instance, the authorities regulate financial law—which defines the scope of financing options available to SMEs and micro-enterprises for innovation—create legal frameworks for the existence of web platforms, and impose taxes, which concern not only the entrepreneurs and CFPs, but also investors.

Using the CF value constellation model (

Figure 1) and the seven Co-s model proposed by Quero, Ventura, and Kelleher [

46], we have devised a map of value types co-created with reference to the interactions between groups of agents. According to the 7 Co-s model, crowdfunding leads to the co-creation of values such as co-ideation, co-design, co-evaluation of ideas, co-testing, co-launching, co-financing, and co-consumption. Within the constellation, the character of the connections/interactions between the agents is tied to the type of co-created value in question. The network of these mutual connections is shown in our relations matrix (

Table 3) [

46,

48,

56,

57,

58]. On this map we can identify what values are co-created with the interactions described above.

The co-created values may be divided into three main groups: those related to (1) strategy and product concept, including concept development, verification, and testing; (2) finance; and (3) production, market launch, and sales.

In the first group, the agents include entrepreneurs, the crowdfunding platform as a mediator, and the broadly understood crowd. Positive crowd response to the product and the prospect of active participation in product development may attract a group of active investors (resource providers). In that case, the entrepreneur has achieved the funding goal, and may proceed with production and sales. The crowd plays an important and unique role in the process. In the beginning, it participates in project design, assessment, and testing, which relate to interactions 1, 2, and 3. Then, it morphs into a capital provider (interaction 6). Finally, it becomes a group of consumers, which relates to interaction 4 or interaction 5. With the lively information flow and continuous communication at all stages—before resource acquisition, throughout the funding period, and during project implementation—all agents participate in the co-creation of values, with the influence of government on all of these agents. The process relies heavily on the CFP, which provides an arena for information exchange and communication between all participants, ensuring that everything runs smoothly from the technical, legal, and organisational standpoints. Therefore, apart from their role in fundraising, CFPs serve as useful marketing tools.

Let us emphasise the differences in value co-creation arising from the business model employed in a given crowdfunding project. In reward-based crowdfunding, which relies on recompense or the pre-purchase mechanism, the capital is provided by customers. Consequently, these customers are referred to as backers (rather than investors), and their interactions correspond to interactions 4 and 5 in the value constellation model. Meanwhile, equity CF and crowdlending require the participation of investors, who provide capital and may or may not become customers. Alternatively, the enterprise may acquire customers who will not, however, pledge funds to the campaign. Therefore, value co-creation in equity CF and crowdlending is a more complex issue, as reflected in the value constellation model (interactions. 4, 5, and 6). A detailed analysis of values co-created in the CF ecosystem for SMEs is presented later in this paper.

4.2. Crowdfunding —A Map of Values

For an enterprise, the choice of financing options is a critical decision [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60], contingent upon the selected business strategy. To analyse this strategy, Norton and Kaplan propose a balanced scorecard that includes four perspectives/areas of business activity—learning and growth, internal (operation), customer, and financial [

61] —and determines value drivers significant for each area [

61,

62]. This method has the key advantage of measuring the factors that affect both financial and non-financial (intangible) value, and examining their mutual relations [

59]. A harmony between all of the perspectives is the main prerequisite for boosting company value. The value creation factors identified by Norton and Kaplan correspond to those proposed by Walters [

5,

63] and Rappaport [

12], whereas the fundamental determinant of company value growth is the increased free cash flow. Based on free cash flow, we can assess company value with EVA (economic value added)—a measure calculated with the following formula [

17,

61,

62]:

where: Tax = income tax rate; Cost of Capital = the cost of CFP management and other fundraising-related activities; Sales = the worth of sales generated by the CF campaign and its growth as compared to past performance in the period preceding the campaign; and Operating Costs = costs generated by CF related to the value of products sold and/or to the adjustments made to satisfy customer requirements.

In essence, to calculate EVA is to translate the operational performance of the enterprise into cash flow. This measure is used to assess short-term value growth—in an annual perspective at the maximum (as it relies on financial results)—and serves as an indicator of value growth or degradation for the owners. By determining which values co-created through CF may affect the value drivers in each perspective in the first place and, in the longer run, revenue and expenditures, we will finally assess their impact on EVA.

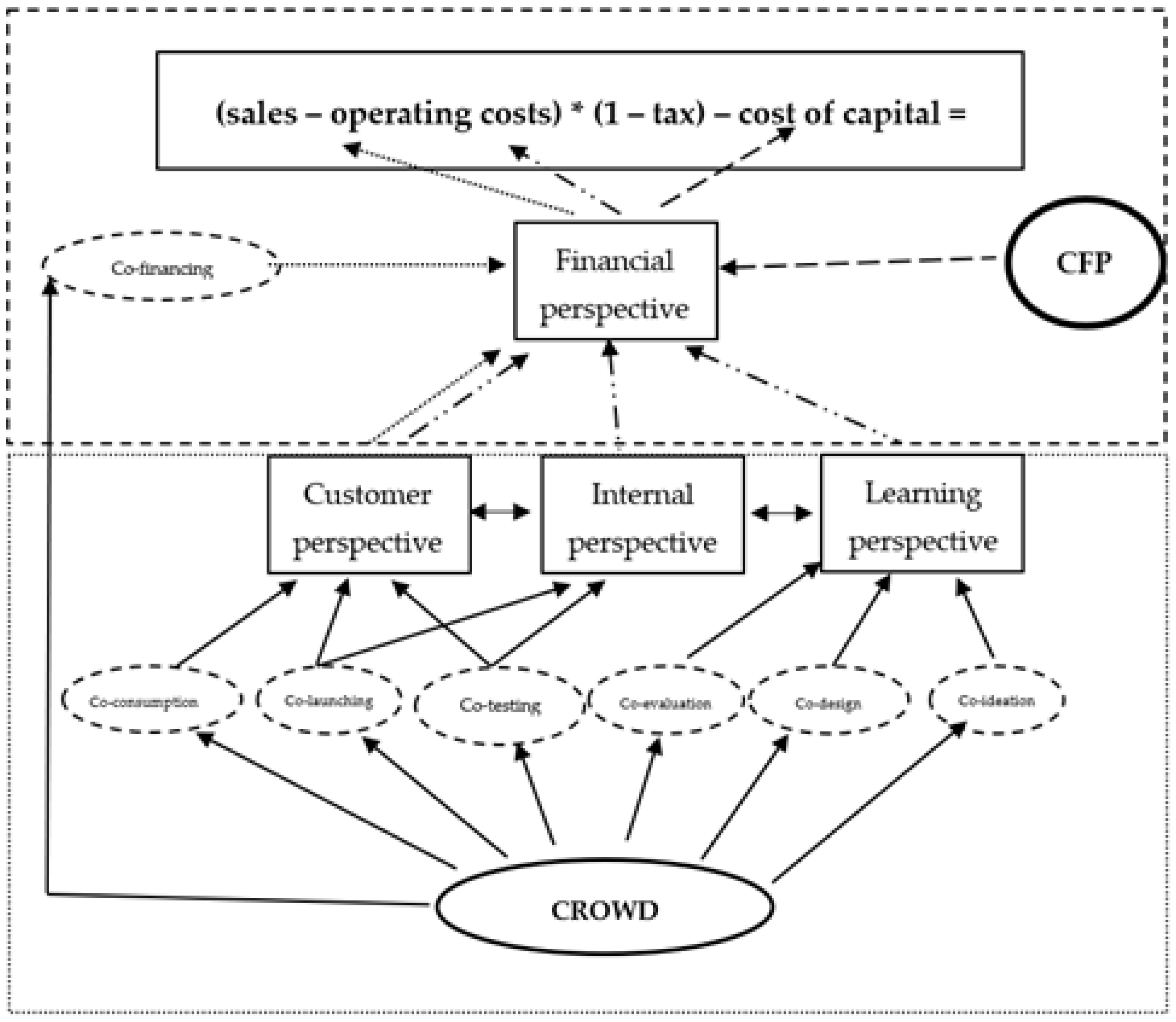

A visualisation of these connections is shown in

Figure 2. The graphic consists of two areas: the first represents the non-financial activity (customer, internal, and learning perspectives) of the enterprise, including the spheres of knowledge and growth, whereas the other illustrates the sphere of finance. The map of value creation in the enterprise is simultaneously modelled, which serves to present the position of the remaining agents in relation to the indicated areas of value creation.

Table 3 shows that, with the exception of co-financing, all co-created values fall in the non-financial area. The arrows in

Figure 2 pointing from the crowd towards various perspectives symbolise values co-created in the CF ecosystem that exert a particularly marked influence on the (non-financial) area in question.

In the perspective of learning and growth, key value drivers include the human capital (e.g., knowledge, abilities, skills, staff motivation), information capital (various types of assets, databases, systems, and networks for knowledge acquisition), and organisational capital (including organisational culture, leadership, and the compatibility of people and the strategy). In the context of the interplay within the CF ecosystem and its value constellation, the key co-created values include co-ideation, co-design, and co-evaluation of ideas. Networking and crowdsourcing—both typically present in CF—allow greater access to tangible and intangible resources. Consequently, they are potentially helpful in acquiring knowledge or skills, which could mean life or death for the project [

64,

65]. From an entrepreneur’s perspective, collective knowledge of the crowd may be exploited to verify project aims, crystallise the set of its distinguishing features, or polish the presentation. The degree of the enterprise’s involvement in co-creating value determines the success of the CF campaign and future development of the project. The values must remain equally important in all CF models. The information flow and communication between the crowd and the enterprise produce the signalling effect, which allows the investor/customer (who will eventually emerge from the crowd) to discount the products of future activities [

66]. Signalling fosters better decision-making in the scope of investments [

67] and/or purchases (risk mitigation) [

68]. Information flow and communication reduce the effect of asymmetrical information in relations between the investor and the entrepreneur, which mitigates the risk of failure for the investor [

67,

68]. Thus, the values co-created in this sphere are also of material importance for other perspectives of the customer, finance, and internal processes within the enterprise.

Internal processes include operations (e.g., purchases, production, distribution, operational risk); customer management (e.g., customer selection, acquisition, retention); innovative processes (the identification of new opportunities for growth, new product portfolios, new projects and means for their implementation); and regulatory and social processes. The internal perspective involves product conceptualisation throughout the CF campaign and upon its conclusion, during the production stage. The focus falls on the opportunities to acquire and select clients, which facilitates market launch (co-launching), as well as the impact of co-created values (co-testing) on innovation processes concerning the product itself, its production, and its distribution. The entrepreneur’s expertise affects operational expenses on internal processes and the corporate image imparted to the customers [

69]. The verification of existing solutions against the expectations and ideas voiced by the crowd allows the enterprise to tailor its processes to the identified needs, through internal innovation and otherwise.

Internal processes depend on external circumstances created by the government—one of the agents included in the value constellation model. From the internal perspective, the government impacts the company’s operation through a range of legal and formal frameworks concerning business activity. Regardless of the selected business model, some level of value co-creation in this perspective is unavoidable due to its ties to the perspectives of learning and growth. Since product testing involves enterprises and members of the crowd, co-created values affect not only the internal perspective, but also that of the customer.

Customer perspective is a unique area of any fundraising strategy based on CF. Obviously, the link between the customers and capital providers is stronger in reward-based CF than in crowdlending or equity-based CF. However, in accordance with value-based management, maximising value drivers important for the customers will improve customer acquisition regardless of the selected CF model. The value drivers typically listed in this perspective include price, product quality, availability, quality of service, customer relations, and brand image. The Norton–Kaplan model prioritises active management of customer relations (the growth of sales), which—in the case of CF—is a natural corollary of the communication on the web platform and the fruit of the earlier value co-creation at the stages of ideation and evaluation of ideas. It is at this point that the price and sale volume first come under negotiation—far sooner than traditional business conventions would dictate. The crowd and the entrepreneur engage in an animated information exchange, which not only helps with the pricing but also fosters the customer–entrepreneur relationship [

70,

71]. The entrepreneur gains recognition and may start building trust. Much like from the internal perspective, familiarity with customer expectations allows the entrepreneur to redirect the necessary resources to satisfying the identified needs and requirements (cost reduction) [

71,

72]. Furthermore, it gives the entrepreneur a chance to investigate the opportunities for growth and assess the profitability of the new product.

4.3. Financial Perspective—The Impact of Co-Created Values on EVA

The financial perspective summarises how all of the decisions and activities included in other perspectives translate into cash flows. Value drivers include cash flows related to sales, operating costs, cost of capital, and interest rates.

Figure 2 presents the necessary expenditures in these perspectives with line 3, while the revenue is marked with line 1, and cost of capital with line 2. A sales boost improves cash flows, whereas an increase in operating costs or the cost of capital has the opposite effect. Regulatory processes concerning tax rates and tax rules are another factor diminishing the amount of cash available to the owner. Upon analysis, the revenue generated through crowdfunding may be divided into two types: investment-based (in equity crowdfunding and crowdlending) and sales-based. Sales revenue is generated through client acquisition during the campaign (regardless of the adopted CF model) and product sales (as in reward-based crowdfunding). The generation of sales revenue adds the co-created value of co-financing. EVA rises together with the amount of resources collected from the investors and the number of clients acquired throughout and after the campaign. Campaign management, testing, product modification, production process adjustment, and distribution all entail operating costs, reducing the final income. The volume of operating costs hinges on activity in the perspectives of learning and growth, internal processes, and the customer.

The cost of capital in equity- and reward-based CF includes mainly the expenditure made on CFP management. Reward-based CF entails additional expenditure on the rewards. In the case of crowdlending, the cost of capital comprises CFP management plus interest. All of the relevant costs are compared against interest rates on loans [

70,

71,

72], allowing the evaluation of the profitability of launching a CF campaign. From the entrepreneur’s perspective, what matters is not only the CFP management cost (transactional cost), but also the potential funding amount, which will affect the cost of capital. The use of equity-based CF or crowdlending increases the value of equity or borrowed capital, and alters the capital ownership structure in the company. With reward-based crowdfunding, the capital structure remains unchanged, for the investors receive no shares and the resources acquired are non-refundable, as opposed to loans.

The use of CF mitigates business risk for both the investor/customer and the entrepreneur. It does not eliminate it altogether, since innovative projects typically funded through CF are high-risk by default. The risk–return relationship theory claims that the higher the risk, the higher the return on the investment [

71]. If we consider this argument as decisive for our investment in CF, we should expect return rates at a rather substantial level, which reveals the importance of the values co-created through CF. It is precisely these values that, by reducing the effect of asymmetrical information in the investor–entrepreneur relationship, mitigate the risk of project failure [

64,

66]. If the added value arising from CF is to be positive, the generated revenue must exceed operating costs and the cost of capital. In that case, the use of CF may be deemed a success. However, if the crowdfunding campaign goes adrift or fails to raise the required amount of funds, the entrepreneur has to look for other financing options or reassess the entire process, from the concept itself to campaign management. Finally, a failed CF campaign may impair the company’s image.

5. Discussion

Company value may be increased through a wide range of activities, including the choice of financing sources. Crowdfunding as a financing instrument presents an alternative to the conventional bank loans typically used by SMEs. This paper examines how the use of CF by an enterprise affects its value.

Our inquiry into the first research question: “Are all participants in the CF ecosystem involved in the co-creation of value?” has yielded a positive answer. Upon an analysis of interactions between individual agents active within the CF ecosystem, conducted with reference to the value constellation theory, it has been established that all participants in the CF ecosystem are involved in the co-creation of value. Thanks to the co-creation of value in crowdfunding, projects can be assessed from the social, environmental, and financial points of view, facilitating decision-making by the entrepreneur. The co-created values of the 7 Co-s model have been referred to the value constellation model and linked to all of the relationships occurring in their mother ecosystem. The values are clearly interdependent, as the failure to generate a satisfactory level of co-created value at the outset (concept stage) drastically limits the chances of co-creating other values later on. The specific value flow within the CF ecosystem follows a triangular model: Co-ideation, co-evaluation of ideas, and co-design form the base of the triangle. Their implementation attracts funding, but also creates an opportunity for testing, facilitates market launch and, finally, streamlines consumption. Meanwhile, the funds raised support the implementation of values within the enterprise itself. Let us note the sequential aspect of value co-creation; if the creation of values is neglected early on, the CF campaign cannot proceed to the final phase—that is, the acquisition of funds.

The second question: “Does CF contribute to creating new value in all of the perspectives: of learning, the customer, internal processes (operations), and finance (does it impact the value of future cash flow?)?” has also yielded a positive answer. Our analysis of co-created values referenced against the key value drivers relevant to each perspective reveals that CF contributes to value creation in the perspectives of learning, the customer, and internal processes, as well as affecting cash flows. The analysis confirms that co-ideation, co-evaluation of ideas, and co-design exert the greatest direct impact on the perspective of learning and growth, and the greatest indirect impact on the perspective of internal processes. Similar interplay may be observed between the perspectives of the customer and internal processes, as in both cases the co-created values (co-testing, co-launching, and co-consumption) affect the relevant value drivers. Additionally, the co-created values affect one another, as the enterprise and the crowd exchange information and learn. Successful co-financing testifies to the entrepreneur’s competence in the areas of satisfactory communication with the investors and cooperation with the crowd. Regardless of the selected business model, crowdfunding leads to the co-creation of all of the values discussed. In reward-based CF, product-related values outweigh co-financing. In the other models, co-financing takes precedence, which flows from the operational differences between the models. In reward-based CF, fundraising involves an exchange of funds for the product. In the two remaining types, it requires a traditional investment, characteristic only in the fact that additional resources may come from product sales. The roles of the investor and the customer are kept separate; therefore, the entrepreneur should adapt the CF model to their expectations in terms of values. Regardless of which model the entrepreneur uses, the fact of running a crowdfunding campaign will shape internal processes, including a better understanding of the expectations and needs of individual actors, contributing to the adaptation of internal processes to the needs of sustainable development (cost reduction and better adaptation of products to the needs and requirements of customers and the environment).

Even upon the establishment of the position of co-created values within the CF eco-system, their links to the various areas (perspectives) of the framework, and their impact on value drivers, the last question “Does the use of CF drive company value?” escapes an unambiguous answer—particularly in the context of the assumed impact of crowdfunding on EVA. Apart from knowing (1) the impact of individual value drivers on EVA and (2) the impact of values co-created through CF on cash flows, the entrepreneur needs to be certain that (3) the revenue will exceed the costs. Theoretical analyses fail to fully corroborate the accuracy of the third proposition. The use of CF may increase company value or not. In some situations, the enterprise may fail to acquire funding or increase sales, but still bear the costs of managing the CF campaign. Keeping in mind the interplay between co-created values, we can unequivocally declare that this outcome is possible if the company fails to co-create values at the early stages of the value constellation. This conclusion seems self-evident, as it finds confirmation not only in theoretical analyses, but also in the research of authors who list causes of CF campaign failure/success:

Project time and campaign goals [

64,

65,

70];

Duration of the campaign [

68];

The entrepreneur’s involvement with the CF campaign [

38,

73];

Financial target [

74,

75]—an overly ambitious financial target increases the risk of failure.

In other words, the success of any CF campaign depends on factors related to the concept, the interplay between the crowd and the entrepreneur, and the amount of funds required. An awareness of the impact of co-created values on the enterprise and the causes of their success/failure may provide valuable insights for the preparation and management of future campaigns. The value-based management theory combined with the value map referenced against the values co-created through CF yields one fundamental conclusion: the company and its value will grow only if all of the co-created values are harmoniously balanced. As co-created values affect value drivers, the harmony between the former will translate into the harmony between the latter (Norton and Kaplan’s value map). For a company that funds its activity through CF, this is a prerequisite of value growth. Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

As demonstrated, the choice of financing sources is a major strategic decision that triggers a host of serious consequences. The type of values co-created through crowdfunding, and their impact on all of the business activity areas/perspectives, may become a stimulus for entrepreneurship and a source of new ideas for growth. They may foster resource acquisition and help to identify key resources. Due to their impact on internal processes, as well as the expertise and skills of the staff and the owners, they may affect company management.

Our analyses have confirmed that crowdfunding—as an example of open innovation due to its use of networking, crowdsourcing, and ICT (information and communication technologies)—bears the following characteristics [

56,

57,

58]:

Key importance of both internal and external knowledge for customers, investors, and entrepreneurs alike;

Key importance of technology flow and knowledge flow underpinning a CF campaign;

Potential to discover new areas of knowledge through communication between the crowd and the entrepreneur;

Need for active management of IP addresses;

Key importance of the mediator—that is, the CFP.

We have also indicated how the crowdfunding features identified so far—listed above—can influence the shaping of a company’s value, which is, added value to the current state of the art concerning CF and SMEs. These findings match the new paradigm for innovation development proposed by Curley and Salmelin [

76], which relies on integrated co-operation, co-created shared value, the construction of innovative ecosystems, existing technological capabilities, and a streamlined process of implementation enabled by the existing network connections [

65]. All of these elements may be found in the CF ecosystem. Technological innovation, which lies at the heart of CF, plays a unique role in value creation and the development of enterprises, as confirmed by Wong, Ho et al. [

77], and Enkel [

78]; their research has demonstrated a strong connection between technological innovation and economic growth. Similarly, the importance of innovation in value creation has been previously confirmed by Griliches [

79] and Aghion and Howitt [

80].

Our analyses reveal that value creation largely depends on information exchange and communication between CF participants. The multidirectional character of the exchange prompts knowledge creation and diffusion within the ecosystem. From this perspective, CF becomes a major external factor driving economic innovation [

2], and may contribute to the sustainable development of enterprises. Information exchange, communication, and networking change the mindset towards entrepreneurship and the disposition to open one’s own business. Thanks to application of the Norton–Kaplan model, our analysis showed that value creation in an enterprise takes place in various areas of its operation, and crowdfunding contributes to a better understanding of the requirements for enterprises related to sustainable management. This is possible thanks in part to constant communication between the actors of this ecosystem, building partner relations and searching for new and better solutions. The concept of sustainable development from the financial point of view of a company using CF means the possibility of creating added economic value, thanks to the possibility of co-creating value by all its participants.

Even though CF mainly involves value creation through the relationships between the crowd and the entrepreneur on the CFP, the role of the government is by no means insignificant or limited to taxation or interest rates. The legal framework affects not only entrepreneurs, but also the CFPs and investors, for no value in the CF value constellation may be created without their participation. In the constellation of values, every agent plays a distinctive role, which should be performed without unnecessary disruptions, and ideally in favourable conditions created by an adequate legal framework. The enterprises resorting to CF rely heavily on the government for access to the foreign markets, which provide a source of both knowhow and funding. Using these resources increases the chances of success and customer acquisition through the campaign.

6. Conclusions

This paper attempts to provide a holistic account of crowdfunding as a financing instrument in the context of creating value for SMEs. This study was carried out due to the important role that SMEs play in the economy, and the search for new methods of financing for them. The decision on the method of financing requires consideration of its impact on the growth of the company’s value. Entrepreneurs strive to increase this value, where EVA is one of the measures used. Analyses of this kind require the study of the mutual influence of various factors. Measurement of the increase in value is extremely difficult because, in addition to financial factors, the increase in the value of the enterprise is influenced by non-financial factors. Therefore, when considering crowdfunding as a way to obtain funds, an entrepreneur should consider what areas of his company’s operation will be affected by the use of crowdfunding, so as to ensure sustainable growth for the company in all of its areas.

The aim of our study was to build a model to show the relationships between non-financial factors generated in the CF ecosystem as a result of interactions between its actors, and then explain how these interactions can affect the financial value creation of SMEs, measured by EVA.

Taking into account the purpose of the research and the complexity of the studied issue, we took into account the Norton–Kaplan model as the leading model, because it takes into account the company’s activities in both the financial and non-financial areas, and shows the relationship between the values created from the knowledge and learning, internal, and customer perspectives, as well as the value created for the owners. The biggest problem turned out to be the reference of the values created in crowdfunding and their impact on the areas of the enterprise, especially from non-financial perspectives. This problem was solved by applying the theory of value creation used to analyse the co-created values in crowdfunding. Due to the fact that Norton and Kaplan’s map takes into account the processes and activities undertaken by enterprises in creating value, the analysis of interactions—and linking them to co-created values—therefore allowed us to relate them to the Norton–Kaplan value drivers, and then to the EVA. As revealed by the analysis of values co-created through CF, and their impact on value drivers relevant to each perspective, the use of CF may become a major factor in company value growth, which is one of the internal factors of entrepreneurial innovation [

68].

The analysis of value constellation allowed us to identify co-created values and their relationships with value drivers in Norton and Kaplan’s map, and finally, how co-created values through value drivers may affect EVA.

The results in the form of the developed model show how the influence of CF on the EVA value can be analysed.

A better understanding of these dependencies gives greater opportunities to properly build a CF campaign and achieve better results—both financial and non-financial.

From the scientific point of view, our research, together with the proposed model, is an attempt to search for a method of measuring the value created by CF for SMEs. Apart from the listing the characteristics of CF, Chesbrough [

56,

57] and Chesbrough et al. [

58] point to the need for new measures in the assessment of open innovations. In an attempt to identify such measures, the authors present their analyses and models on co-created values, the Norton–Kaplan model, and the application of EVA as a measure of value co-created through CF. That first analysis of CF from the financial standpoint has contributed to:

A better insight into the interplay within the CF ecosystem from the financial standpoint of the owner;

Application of the Norton–Kaplan map to analyse the new business model for enterprises using CF;

The theory of finance through the use of value constellation theory to examine the impact of values co-created through CF on value-based management;

The identification of EVA as a measure of CF value.

The conducted research and the presented results have limitations resulting from the adopted assumptions and simplifications, which were used in the development of the Norton–Kaplan model adapted to the needs of the conducted research:

Only CF models such as equity and rewards and crowdlending were the subject of the research. The donation model was not included;

The research did not take into account the types of fundraising. Regardless of the type of fundraiser, it will be a success to raise the required amount for the project, and no success if the required amount is not raised;

In the CF model, we focus on the basic types of interactions occurring between actors of the CF ecosystem without their detailed analysis, which in the case of practical activities should be analysed;

The model and adopted assumptions take into account the actions taken during and shortly after the end of the CF campaign; therefore, the adopted financial measure is EVA. We do not take into account the longer period (2, 3 years) after the end of the CF campaign.

This means that the model developed is fairly general, which has both advantages and limitations. The main advantage of the model is the ability to quickly determine the relationships and their impact on the value of the enterprise, regardless of the CF business model, by analysing the co-created values and linking them to the Norton–Kaplan model. This model can be applied for different types of businesses. However, in order to obtain more detailed data, it is necessary to extend the model adequately to the analysed case. Therefore, the question of how such an analysis could translate into the company’s resources, and not only into the areas of its operation, remains an open question, and is good background for further research. The time constraints appear to be the main limiting factor in the use of the model, as it does not quantify the long-term effects of CF. As is known, many projects, despite collecting funds in the CF campaign phase, are not successful in the long term. Therefore, it is very important to conduct research in enterprises analysing whether CF campaigns have been designed in a sustainable manner, i.e., taking into account the characteristics of CF and the functioning of the enterprise itself.

7. Recommendations for Further Research

Recommendations for further research result from two directions of research presented in the article: a literature review, and the qualitative analysis of CF carried out for CF from the entrepreneur’s point of view. Our analyses focused on the possibility of using EVA and the Norton–Kaplan model to measure the increase in value of SMEs using CF. The analysis was carried out only from the entrepreneur’s point of view; therefore, the following questions arise:

What other value measurement methods can be used to measure the increase in value of a company using CF?

Which co-created values are most relevant to other ecosystem participants?

Could the analysis of co-created values in crowdfunding contribute to the success of crowdfunding campaigns and the company’s long-term success, and to what extent?

The subject of the analysis in the article is CF as a source of financing. For a more complete picture, however, other sources of financing should also be included in the analyses as, for entrepreneurs, internal finance and debt financing are of key importance for the creation and development of an enterprise. Walthoff-Borm, Schwienbacher, and Vanacker [

81] point out that external equity financing (e.g., venture capital, angel financing, etc.) is usually unavailable, or entrepreneurs are reluctant to attract it for fear of losing independence. They also note that previous research has focused on factors that influence funding success on equity crowdfunding platforms, but lacks a detailed understanding of the factors that drive companies to seek equity crowdfunding [

81]. The authors argue, based on the pecking order theory, that companies use crowdfunding platforms as a “last resort”—that is, when they lack internal resources and additional debt capacity. In the absence of internal funds, entrepreneurs will look for debt financing, and only choose external equity financing—including equity financing—as a last resort [

82]. Crowdfunding is promoted not only for fundraising, but also for information gathering, and is a complement rather than a substitute for traditional bank financing [

83]. Fourati’s research results confirm that crowdfunding as a screening tool improves the information environment of the entrepreneur and reduces the problem of moral hazard [

82].

As the conducted research has shown, the situation of banks and entrepreneurs is important for decisions about crowdfunding. According to Blaseg and Koetter, crowdfunding is much more likely for new ventures that interact with distressed banks. Innovative financing is therefore of particular importance when conventional financiers struggle with crises [

83,

84]. Similarly, according to Attuel, the instability of banks may induce borrowers to use crowdfunding as a source of external financing [

85]. Blaseg and Koetter emphasize the existence of costs related to the equity crowdfunding (ECF) due to early public disclosure of entrepreneurial activity, the costs of communicating with large investor pools, and the dilution of capital, which may discourage future equity investors. They also emphasize that equity crowdfunding (ECF) has potential benefits that can be attractive to quality entrepreneurs, including quick access to a large pool of investors and getting feedback from the market [

83,

84].

It is worth noting that banks are aware of the emergence of a new type of competitor in financing entrepreneurial ventures, and are starting to cooperate with crowdfunding platforms in various ways. In Attuel’s opinion, banks need to invest in crowdfunding. They should create partnerships to track an as-yet immature but very promising market. Being associated with platforms, they are able to identify the needs and expectations of the market and fulfil their mission of financing the economy [

85].

Today, the banking and financial ecosystem is greatly influenced by digitization and the resulting development of FinTech, as pointed out by Moussavou [

86]. The competition imposed by these new entrants prompts banks to develop their absorption capacity (AC). Moussavou points out that identifying and analysing banks’ AC terms and conditions to integrate crowdfunding—one of the most dynamic FinTech sub-segments in recent years—will allow banks to keep pace with the evolving financial industry by incorporating commercial services and models, leveraging their own strengths [

86].

Therefore, there is a need to conduct a comparative study of CF and bank loans in the context of the values co-created for both sources, especially since credit is one of the most common sources of financing for SMEs, next to personal funds and other sources of financing. These analyses will allow the determination of the competitiveness of CFs in relation to a bank loan in this context (creating financial and non-financial value). The results of the study will indicate further directions of the development of CF as an alternative source of financing, and answer the question of whether crowdfunding is a competitive, substitute or final source of financing.

The analyses also show the importance of information exchange and the great importance of communication for the co-creation of value through CF platforms, which is why another research direction is the analysis of the functioning of the platforms, and the proposals for modifying their functioning were the most beneficial for all participants.

In a broader sense, it is worth asking: How do the co-created values in CF support green financing? Answering this question may have an impact on future legal regulations supporting or not supporting this type of financing.

Finally, the set of connections discussed here needs further confirmation in empirical research conducted amongst SMEs. Such research should aim to investigate the perception of CF as a source of value for enterprises that have used, have not used, or have unsuccessfully attempted to use crowdfunding to finance their activity. A confrontation of the findings yielded by theoretical and empirical research will reveal the importance of individual value drivers and their interplay for SMEs in the context of value creation through CF. Additionally, it may show which factors are valued, underestimated, and overestimated by the enterprises. Next, there is a need for further research based on EVA—the value created through CF for the owners—since the analyses have confirmed the existence of a connection.

Hence, entrepreneurs’ answers to the following questions would be interesting:

Is the primary goal and value for enterprises using CF only to obtain funds, or are other values important? If the latter, which ones?

Are businesses that only want value in the form of cash more likely to be successful in the future, or does it not matter?

Indubitably, in light of all of the aspects of value creation discussed, crowdfunding presents an attractive financing option [

87]. The procedures required to launch a crowdfunding campaign are relatively simple. However, due to the complex interplay between all of the agents involved, the whole mechanism requires a profound understanding for the entrepreneur wishing to enhance their prospects of success.

communication and information exchange;

communication and information exchange;  transfer of financial resources or/and products;

transfer of financial resources or/and products;  transfer of crowd.

transfer of crowd.

communication and information exchange;

communication and information exchange;  transfer of financial resources or/and products;

transfer of financial resources or/and products;  transfer of crowd.

transfer of crowd.

the impact of crowd through co-created values on perspectives;

the impact of crowd through co-created values on perspectives;  interactions between perspectives. Cash flows:

interactions between perspectives. Cash flows:  1. Revenue from investments in equity-based CF and crowdlending; revenue from product sales;

1. Revenue from investments in equity-based CF and crowdlending; revenue from product sales;  2. Cost of capital (expenses on CFP management and other fundraising-related activities);

2. Cost of capital (expenses on CFP management and other fundraising-related activities);  3. Operative costs (related to the perspective of the customer, learning and growth, and internal processes).

3. Operative costs (related to the perspective of the customer, learning and growth, and internal processes).

the impact of crowd through co-created values on perspectives;

the impact of crowd through co-created values on perspectives;  interactions between perspectives. Cash flows:

interactions between perspectives. Cash flows:  1. Revenue from investments in equity-based CF and crowdlending; revenue from product sales;

1. Revenue from investments in equity-based CF and crowdlending; revenue from product sales;  2. Cost of capital (expenses on CFP management and other fundraising-related activities);

2. Cost of capital (expenses on CFP management and other fundraising-related activities);  3. Operative costs (related to the perspective of the customer, learning and growth, and internal processes).

3. Operative costs (related to the perspective of the customer, learning and growth, and internal processes).