Abstract

The benefits from educational travel programs (ETPs) for students have been well-documented in the literature, particularly for programs looking at sustainability and environmental issues. However, the impacts the ETPs have on the destinations that host them have been less frequently considered; most of these studies focus, understandably, on destinations in the Global South. This paper draws on a framework of sustainable educational travel to examine how ETPs affect their host destinations in two case study destinations, based on the author’s professional experience in these locations, interviews with host organizations that use the lens of the pandemic, and information from government databases. The findings highlight an awareness of the sustainability of the destination, the importance of good, local partnerships with organizations well-connected in their communities, and educational activities that can benefit both students and hosts. Nonetheless, we have a long way to go to understand the full impacts of ETPs on their host destinations and thus truly learn to avoid them.

1. Introduction

In 2014 [1], several colleagues and I developed a framework for sustainable educational travel and identified important research topics that could help guide the development of more sustainable educational travel programs (ETPs), including ones that address the program–host destination relationship. Awareness of host-related impacts is essential, both from a perspective of treating host destinations that support ETPs ethically (including partners, the communities, and the natural environment), and educating student participants genuinely about potential problems that arise through travel, and thereby enabling upcoming generations of travelers to confront similar issues in their future travels. This last point is particularly pertinent, given that participants in ETPs often become repeat travelers, including returning to their original study destination [2,3,4]. Short-term ETPs are perhaps at a greater risk for adverse host-related impacts as instructors might rely less on partnerships with host institutions, and students have less time to engage in and adapt to the host community culture [2,5]. Further, students’ educational experiences appear to be less transformative on short-term programs [6], so any educational offset would be more limited.

In this paper, I employ two destinations as case studies where I have developed and led short-term sustainability-themed ETPs to help elucidate good practices for working with host destinations. After first reviewing the recent literature on educational travel as a tool for teaching about environmental and sustainability issues and the impacts programs can have on their host destinations, I extract a framework from the 2014 study [1] about how ETPs should interact with their host destinations to examine considerations of destination sustainability, the role of partnerships, and types of educational activities that can benefit both student participants and the host community. Since the COVID-19 pandemic took place while I was developing this paper, I also take advantage of insights from host institutions in both destinations regarding what the pandemic has revealed about the importance of ETPs in the destinations. The ETPs in the case studies (and the topic of this Special Issue) focus on sustainability and environmental themes; accordingly, this paper will relate most strongly to short-term ETPs that have a sustainability focus. Nonetheless, many of the observations apply to all ETPs and their host destinations in general.

1.1. Brief Review of Educational Travel Programs

Educational travel programs, such as study abroad, service trips, and field schools, are an important pedagogical tool in higher education, with the potential to provide powerful learning experiences for students. Studies have indicated that educational travel programs improve students’ topical knowledge, language skills, and intercultural competencies, e.g., [7,8,9]. Further, indirect benefits have included improved environmental awareness and a greater likelihood to engage in more sustainable behaviors, regardless of the program focus, e.g., [4,10,11]. Consequently, many universities employ these programs to contribute to a mission to develop global citizens [12,13]. Even more effective at achieving sustainability-related outcomes are the programs that specifically focus on issues of the environment and sustainability [3,14,15]. Several studies have demonstrated that learning outcomes for pro-environmental behaviors are much more significant on sustainability-focused ETPs versus other ETPs [16,17].

An important aspect of all of the programs studied above was an intentional pedagogical approach to engage students actively and experientially. In general, an ETP is not automatically an effective learning experience [18]. To maximize learning outcomes, ETPs must deliberately design learning activities and program structures [6,18,19,20]. Pedagogical approaches used in such programs provide opportunities to educate students about various sustainability concepts, issues, and practices in ways that generate lifelong learning; they can also provide benefits for local communities and improve sustainability in general. Kilgo and others [21] found that study abroad (i.e., ETPs), as well as two approaches used in ETPs, undergraduate research and service learning, provide positive impacts on student learning. All three of these are recognized by the Association of American Colleges and Universities as high-impact educational practices. Research service learning, which envisions “research as service [22]”, may be a way ETPs could avoid some of the issues associated with service learning (considered below) while gaining benefits associated with research [2]. Research service learning, as well as participation in citizen science programs, can also serve as important vehicles to educate students about ecology and the environment [23].

Citizen science engages volunteers, including groups of students, to collect real-world data as part of scientific research projects. Participation in citizen science engages students in a large-scale research project and provides interactions with scientists. Citizen science programs can help participants to understand ecology and sustainability better and allow them to understand how research is done [23,24]. Dunn and others [25] argue that engaging citizen science in science education is an important next step, as it confronts students with what is not known rather than teaching them what is. Recent reviews of citizen science projects [26,27,28] further confirm the benefits that the projects can provide: they generally produce positive, albeit variable, learning outcomes, including increased knowledge, improved attitudes towards nature, and more environmentally friendly behaviors. However, as Bela and others [27] noted, these outcomes often take place in informal and unstructured settings. Sauermann and others [24] also noted that participation in citizen science programs is often lacking. Therefore, it stands to reason that a citizen science project embedded within an ETP could provide the formalized and structured setting to enhance gains in learning and provide citizen science programs with dedicated participants over time.

1.2. ETP Impacts on Host Destinations

Despite the effective learning that can take place on ETPs, particularly when properly designed, impacts to host destinations are almost inevitable. Perhaps one of the more pertinent statements about strategies to deal with negative impacts from ETPs came from Dvorak and others [29]. The authors provided three possible approaches to deal with the problematic carbon emissions produced by ETP travel. First, one could assume the benefits for students outweigh any impacts from climate change and thus do nothing. Alternatively, one could assume that the dangers of a warmer planet greatly outweigh any benefits of the programs and stay home. Lastly, one could take a middle road where programs try to mitigate climate impacts as best they can and use the program as a chance to confront students with these emissions and empower them to make relevant changes in their own lives and communities. This argument also applies to other types of ETP impacts on host destinations. As some in the literature discuss [1,18,30,31], it would be unethical to ignore negative impacts on communities, no matter how great the benefits are for students. Thus, we need to take the middle road at addressing and resolving the impacts on the host destinations and use the experiences to educate students to be more responsible.

Lutterman-Aguilar and Gingerich [18] wrote in 2002 that ETPs should incorporate members of the host community to help facilitate experiential learning but advised that the program-host relationship should be reciprocal and mutually beneficial. They further cautioned against “cultural invasions” and placing unprepared and unskilled students in service projects and internships. Almost 20 years later, these problems continue to be reported in the literature, particularly for international service learning programs to the Global South and what Wood et al. [30] termed “vulnerable” communities. Problematic “clashes” of cultures have been reported between foreign students and local communities across multiple destinations with respect to behaviors, displays of wealth, and dress [30,32,33,34], particularly if the students are not adequately prepared for the host culture. In the Global South and vulnerable communities, there are also issues of neocolonialist and superiority attitudes displayed by students and perhaps even reinforced by a program’s inadequate or absent preparation. Ficarra [33] also found that in two popular ETP cities, the influence of U.S. students was evident both in the growing use of English and districts being taken over by “(U.S.) American bubbles”. Disruptive behaviors from students such as drinking or rudeness only further aggravate impacts [30,31,33]. The fact that ETPs tend to go deeper into “backstage” areas, which are not intended for tourism [35], can further exacerbate such issues; uninvaded backstage areas are considered important for local sustainability, as they provide a refuge from tourists [36].

From an economic perspective, several studies report positive benefits resulting from economic income from programs and student participants [30,33,34,37]. One study estimated spending by students [38] was similar to average tourists, and thus providing important income for host communities. Nonetheless, the economic benefits also raise serious concerns related to economic dependency and equitable distribution of the benefits within the host community. Furthermore, there is also a concern about the program’s impacts on local prices and rents [33]. Moreover, students who engage in service projects in these areas for which they lack the requisite skills or language ability can cause problems, demand more time from host organizations, and sometimes harm the very communities they intended to help [32,39,40].

Lastly, ETPs can also affect the host, as well as the global environment. Perhaps one of the clearest impacts is from the greenhouse gas emissions from transport to, from, and within the host destination [29,41]. As climate change disproportionately harms countries of the Global South and vulnerable communities, which are not responsible for historic or current emissions, the emissions created by ETPs from the Global North represent an unfair burden on these communities and one that must be dealt with. Additionally, my 2019 study [35] found potential negative impacts for natural environments in a host destination. Specifically, it found that ETPs visit different sites from tourists, which tend to be more ecologically sensitive and further from roads (i.e., less developed). It also pointed out that ETPs tend to travel in larger groups than tourists and thus have a greater potential of impact per visit.

Referring back to Dvorak and others [29], the only way to eliminate negative impacts completely is not to travel. As this is unlikely to happen in the near future, it behooves ETPs to address these issues honestly and directly. As several authors have suggested [18,30,39,42], institutions need strong ethical guidelines to govern how ETPs interact with host destinations. The challenges these impacts present are also excellent and important opportunities to involve and educate students. The need certainly exists. Not only do ETP participants go on to travel frequently after their studies, but some evidence also suggests that they do not completely understand the role they play in negative impacts. For example, Zhang and Gibson [3] found that former participants recognized negative impacts from their ETPs but failed to express responsibility for them. Fortunately, several authors have utilized educational activities that can help. Dvorak and others engaged their students in developing their own personal carbon offsets that derive from lifestyle changes rather than a third-party purchase. Ling and others [16] use “socio-scientific issues” in their programs that engage students with local stakeholders to debate and develop solutions.

Ultimately, some impacts may be too great. There seems to be a growing call that international service programs need to alter their mode of operations drastically [39,42]. Performing “bad service” is no longer acceptable, and a complete rethinking of what the groups do in the host destination is needed to reframe the visit and the interactions with the host community. In some cases, certain destinations are perhaps no longer suitable and should be avoided.

2. Methodology

This study uses a case study approach to examine how the ETP–host relationship can play out in an effort to craft more sustainable ETPs. Specifically, it uses several important research questions proposed in a 2014 study that developed a framework for sustainable educational travel [1] to examine the case studies. The 2014 framework attempted to provide a holistic understanding of what sustainable educational travel could look like and was based on both the tourism and the educational travel literature. Table 1 presents the questions pertinent to the ETP−host relationship examined in this study, along with the section in which they appear in the paper.

Table 1.

Research framework for study, as adapted from Long and others [1].

While developing this paper, the COVID-19 pandemic was raging around the world (and still is as of now). The pandemic, with lockdowns, travel restrictions, and other regulations, has affected the tourism and travel sectors hard, particularly in regard to international travel. Accordingly, the pandemic also presents an opportunity to understand the importance of ETPs for host destinations and partners, both in the sense of what it has meant and will mean for them, but also what it might reveal about the kind of partnership we have, particularly with respect to issues of dependency and reciprocity. Thus, I describe briefly below how each destination was generally affected and have incorporated insights from the host organizations, as described below.

2.1. Case Studies

The two destinations used here have hosted ETPs, which I have led, and reflect two different settings for ETPs: a tourist town in a populated region and a small town in a remote region, both of which present different contexts to the larger tourist cities examined in [33]. It is also important to note that neither location is located in the Global South or has any particularly “vulnerable communities” (sensu Wood and others [30]). Nonetheless, this does not mean that host destination concerns can be ignored.

2.1.1. ETP Context

Both destinations used here are part of Franklin University Switzerland’s (hereafter referred to as Franklin) Academic Travel program. Franklin is a small, private university in southern Switzerland. Its Academic Travel program is a faculty-led field school program that embeds a 10–14 day travel experience into a semester-long course. Although the structure and pedagogical approach used varies across courses and disciplines at Franklin, the courses share a common basic structure: an approximately six-week pre-travel period on campus, the travel period, and a post-travel period of approximately six weeks back on campus. This structure is very important, as it provides travel leaders the opportunity to prepare students academically, culturally, and logistically for the upcoming travel experience, as well as guarantees an extended post-travel period to reflect upon and process both the academic material learned and the overall experience in the course’s destination. Academic travel courses are offered in every discipline taught at Franklin, including environmental science and studies (the focus of these case studies), as well as several others that teach environmentally or sustainability-related material. The courses are also a requirement of the core curriculum for all bachelor’s degrees (four travel courses required for all B.A. or B.S. degrees).

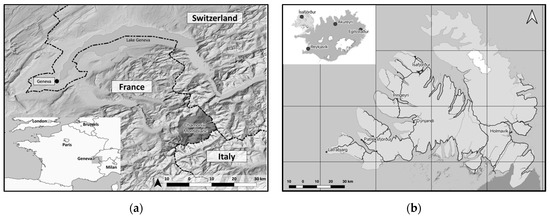

2.1.2. Case Study 1: Chamonix-Mont Blanc Region, France

The Chamonix-Mont Blanc region is located in the département of Haute-Savoie in Eastern France on the border with Italy and Switzerland (Figure 1a). The département had a population of approximately 807,000 in 2017, while Chamonix-Mont Blanc’s population was about 8600 [43]. The region spans 116.5 km2 in the French Alps, including France’s highest peak, Mont Blanc. Its economy depends heavily on the service and transport sector, which accounts for almost 80% of the jobs in Chamonix-Mt. Blanc. The region is a well-known tourism destination for both summer and winter. It is also home to the Mont Blanc Massif, an important natural area with Europe’s largest elevational gradient [44]. Thus, it is an excellent base to study Alpine ecosystems and climate change, which is the focus of the Academic Travel course. The course works with a local non-profit organization that has been conducting environmental research in the area for several decades. The organization generally acts as a host for visiting educational groups, engages them in ongoing research projects, and sponsors several citizen-science programs.

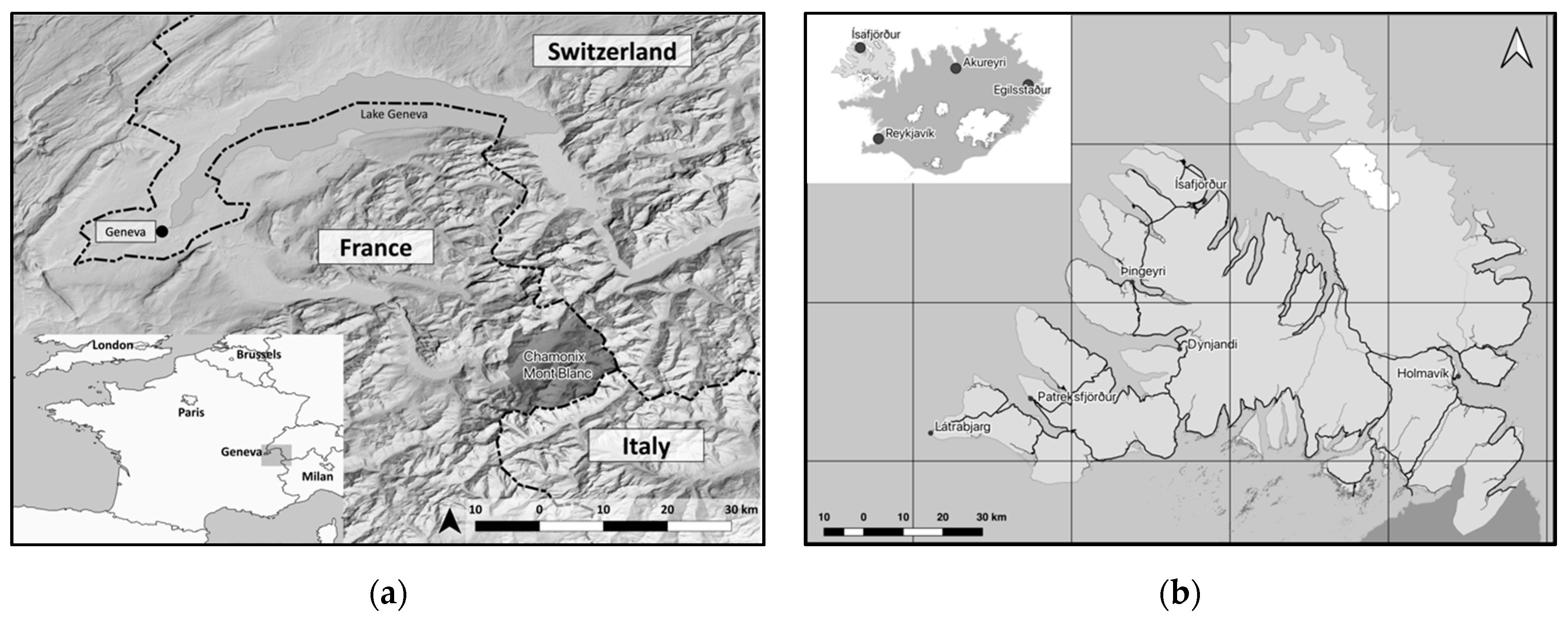

Figure 1.

Case study locations. (a) Chamonix-Mont Blanc case study. Map created by the author in QGIS 3.10, using data from the E.U. [47], Swiss Confederation [48], and © EuroGeographics for the administrative boundaries; (b) Westfjords case study. Map created by the author in QGIS 3.10, using data from the National Land Survey of Iceland [49].

France, as a whole, experienced strict COVID-19 regulations during the pandemic, based on the COVID-19 Stringency Index. The index is a measure of how strict the regulations governing the pandemic were at a given point in time in a given country, measured on a scale from 0 (no regulations) to 100 (all possible measures in place) [45]. It reached a maximum value of 88 during spring 2020 and had an average of 59.6 for the period between January 2020 and June 2021 (data accessed here [46]). Given the improved situation in the summer and early fall of 2020, particularly in the Chamonix region and that of my home institution, my partner institution and I decided to proceed with the ETP we had already been planning pre-pandemic. Each party was of the understanding that we would follow our institutions’ COVID-19 protection plans, which required, among other things, pre and post-travel testing for all program participants, travel in a private coach, mask requirements in all indoor spaces and during certain outdoor activities, social distancing, and limits on group sizes. We were also both prepared to cancel the program at any time if the situation worsened. With Chamonix Mont-Blanc on the Swiss border, this seemed like an acceptable risk.

2.1.3. Case Study 2: Westfjords Region, Iceland

The Westfjords are a remote area in Northwest Iceland (Figure 1b). The region had a population of just under 7000 in 2018; Ísafjörður, the most populated town in the region, had a population of about 2600 [50]. The Westfjords has an area of about 22,000 km2 [51], and its main economic sectors are fishing and tourism. Iceland is a well-known destination for tourism and renewable energies. At the same time, being a remote island bordering the Arctic brings significant challenges both to Iceland and particularly the Westfjords. This has made it an excellent location for several Academic Travel courses that have looked at both sustainability in general as well as sustainable tourism. The courses have worked with a local institution of higher education in the Westfjords that also frequently hosts visiting educational groups.

In comparison to France, Iceland generally experienced the pandemic with less strict measures. Iceland’s maximum COVID-19 Stringency Index value was 65.7, which did not occur until spring 2021; during the January 2020 to June 2021 period, its average index value was 42.9 [46]. Nonetheless, Iceland’s incoming travel regulations often required a mandatory quarantine period for visitors, which made travel for ETPs to Iceland very difficult. I did not have a program planned for Iceland in 2020, so I was not affected directly by the pandemic in this case. However, we are currently planning an ETP in fall 2021 and are keeping a close eye on developments and again developing protection plans; one update from the fall 2020 plan is that all participants must be fully vaccinated against SARS-CoV2 and contingency plans on both sides.

2.2. Data Sources

The data are derived from the author’s professional experiences and observations in leading programs to the two destinations and from government and industry databases. Additionally, I conducted interviews remotely with a representative from the host institution in each destination during November 2020 to see what the pandemic could reveal about the role ETPs play in the respective host destination. Specifically, I spoke with them about how their programs had been affected, any potential impacts in the local community, and how the pandemic might affect future ETPs. The full list of questions is provided in Appendix A.

3. Findings

3.1. Destination Sustainability

One of the most important questions to consider in thinking about a good ETP-host destination relationship is the destination’s ability to support the group sustainably. ETPs are ultimately a part of the overall tourism economy [1,38], and thus an important proxy for how well a destination can sustain an ETP visit relates to how well it can support tourists in general. Even though ETPs do not necessarily frequent the same sites as regular tourists [35], it has been my experience that they often are supported by similar services, particularly with respect to transport, lodging, and meals. Thus, the timing and logistics of ETPs can either complement or exacerbate tourism numbers. The timing of an ETP may or may not be flexible for a university (for example, it may need to happen during an interim period or, in the case of my institution, during the designated time of the semester); the choice of destination may be more flexible. Ultimately, if a destination already suffers from overtourism or if it severely lacks the infrastructure necessary to support tourists, visiting ETPs will be an unsustainable burden on the host destination.

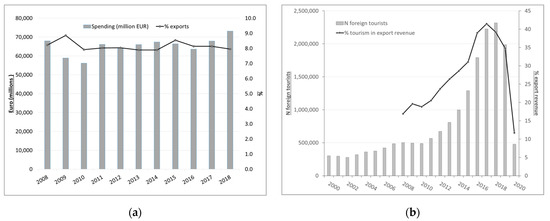

3.1.1. Tourism in Chamonix-Mont Blanc

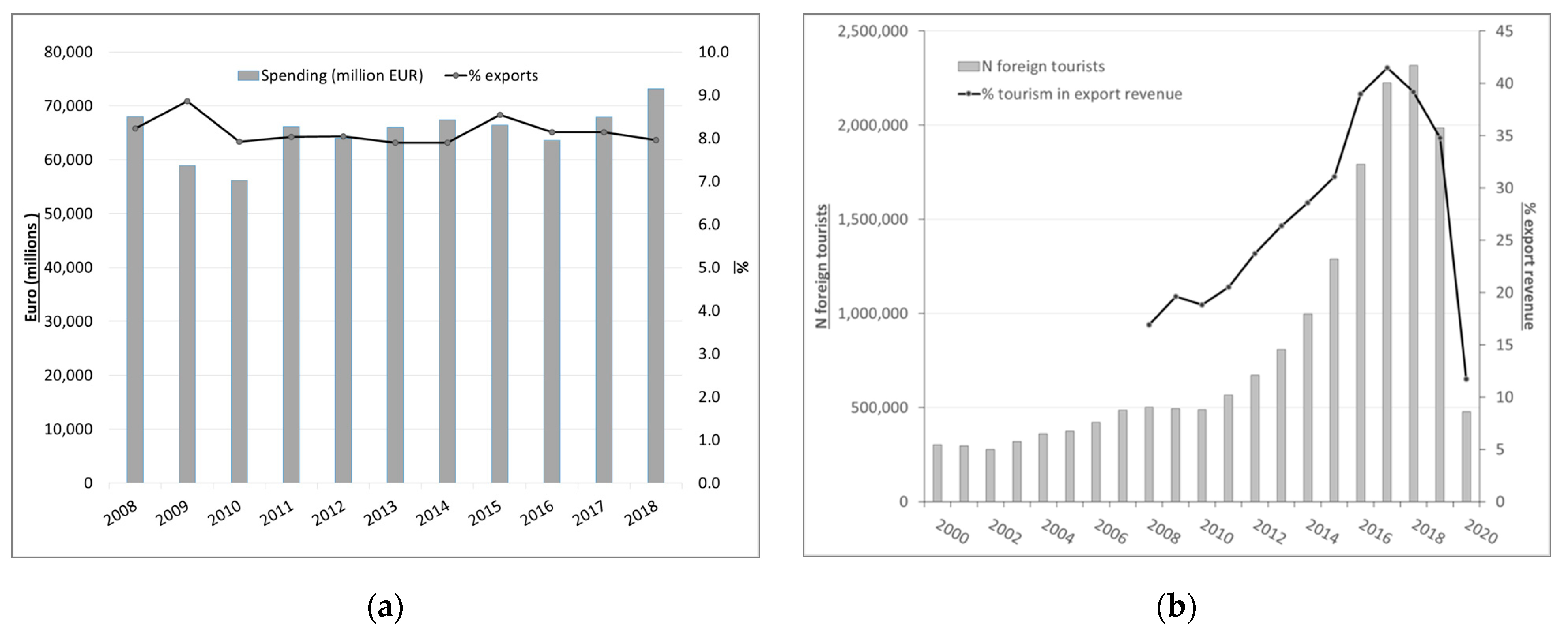

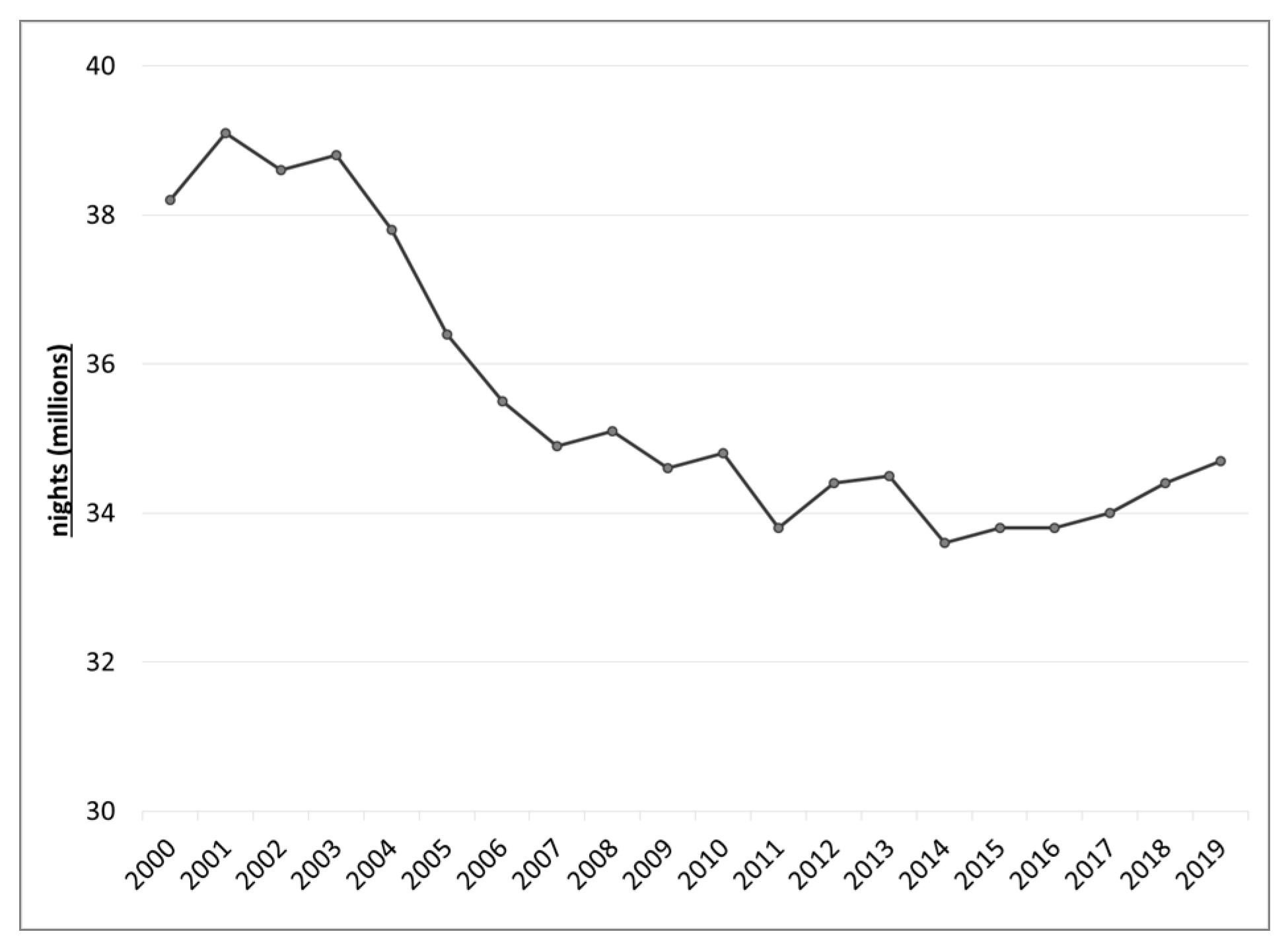

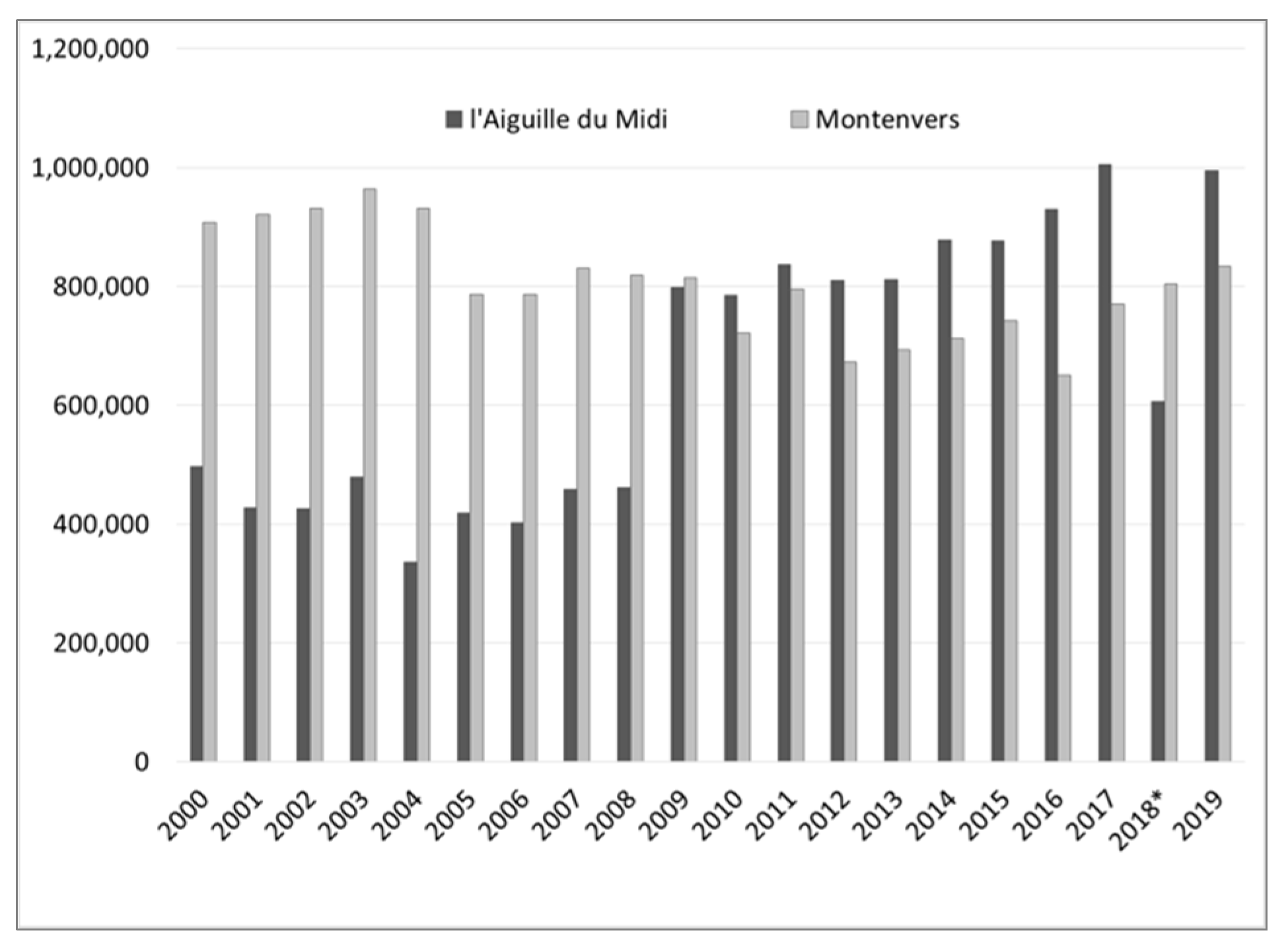

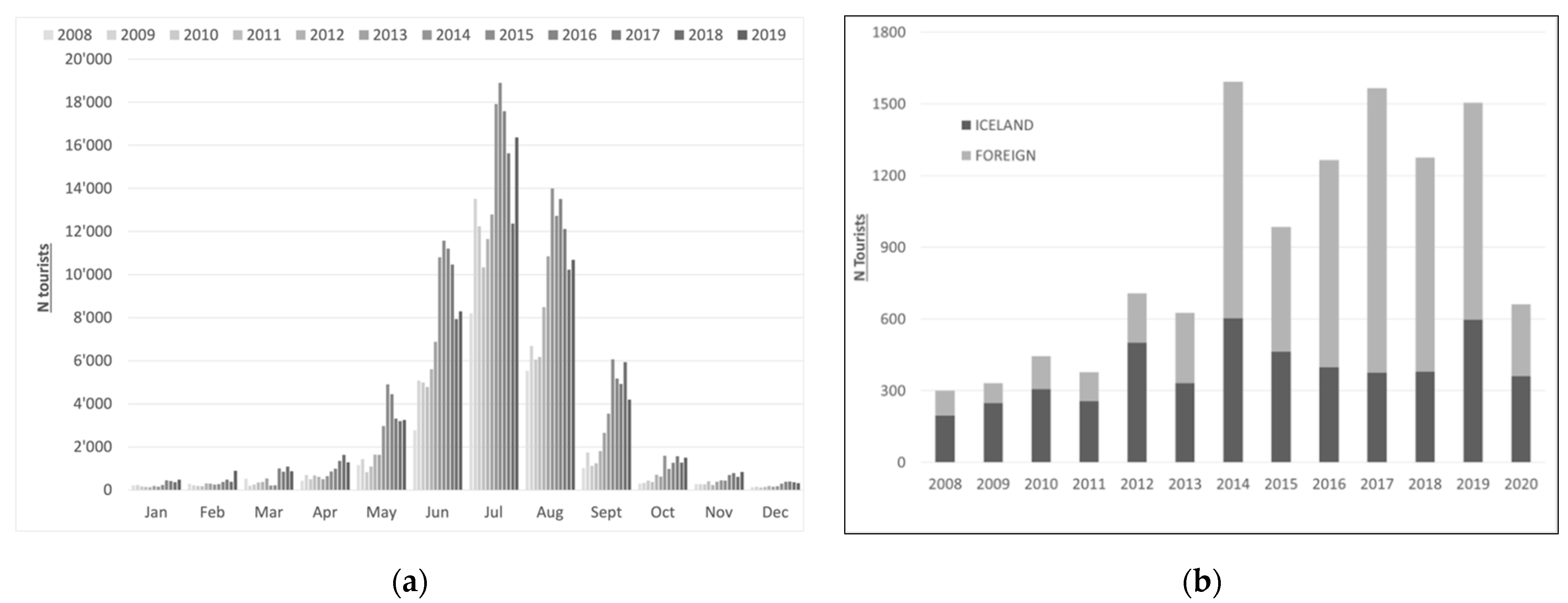

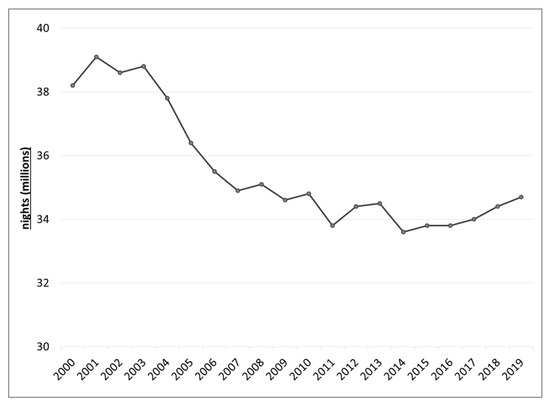

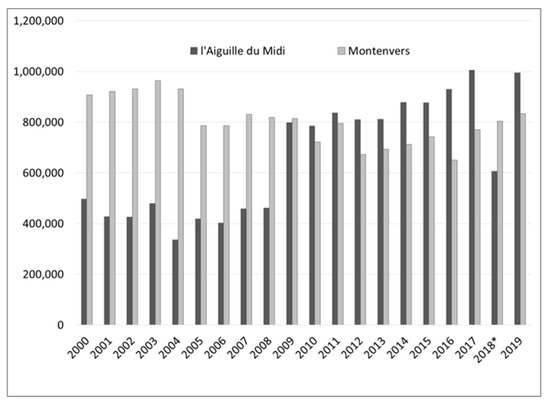

Generally, France is a large country with a diversified economy. Figure 2a shows the relative stability of tourism over the last decade, corresponding to about 8–9% of France’s exports [52]. As mentioned above, the Chamonix-Mont Blanc region depends much more heavily on the service industry, which supports the tourists in the area, the majority (70%) of whom are French [53]. As Figure 3 demonstrates, visitation by tourists has been relatively stable in the Haute-Savoie (the French département in which Chamonix is located) in the last decade, after decreasing in the early 2000s. In Chamonix, the proxy data for tourism are the use of two of the main transport infrastructures (the Aiguille du Midi cable car and the Montenvers train), which both reflect similar trends (Figure 4)—the Aiguille du Midi cable car even shows a general increase in annual visitor numbers over the last 20 years [54]. Located in a mountainous region with multiple ski resorts, Chamonix unsurprisingly receives most of its visitors in the winter (54%) and summer (40%) months [53]. Visits in the fall (October and November) make up just four percent of the annual visits to the region.

Figure 2.

National tourism trends in case study locations. (a) Tourist spending and tourism as a percent of exports in France [52]; (b) foreign tourist numbers and tourism as a percent of exports in Iceland: 2000–2020 [55].

Figure 3.

Tourist nights in Haute-Savoie, 2000–2019 [53].

Figure 4.

Annual trips on the Aiguille du Midi cable car and the Montenvers train in Chamonix (NB: the Aiguille du Midi cable car was closed for part of 2018) [54].

The current official long-term plan for the sustainable development of the region is striving both to diversify the tourism sector as well as to spread out visitation more evenly over the year [56]. From this perspective, ETPs that visit in the off-season, such as the Franklin ETP in October, would contribute to this goal. Further, ETPs also represent a different kind of tourist from a recreational tourist, thereby helping to diversify the sector. Even though ETPs often rely on the same tourism infrastructure, they generally engage in different types of activities than most recreational tourists [35].

When discussing how the pandemic-induced loss of ETPs affected the host community in general, the representative from our host in Chamonix thought that the loss of ETPs had been less of a problem since the region is a major tourism area. ETPs likely make up only a small portion of that sector (NB: whereas the host organization supports 4–5 ETPs per year, there is no good global database with information on the total number of ETPs visiting the area). However, the representative thought that groups, such as mine, which come in the off-season, may be more important, and their loss could have a bigger impact, particularly as we typically use smaller, local providers for lodging and food. Thus, if the region continues its plans to diversify the tourism seasons and types, ETPs might have a larger impact in the future. The representative also hypothesized that there could be longer-term impacts for the region as the ETPs often create repeat visitors to the area, and their participants may also encourage friends and family members to visit as well.

3.1.2. Tourism in the Westfjords

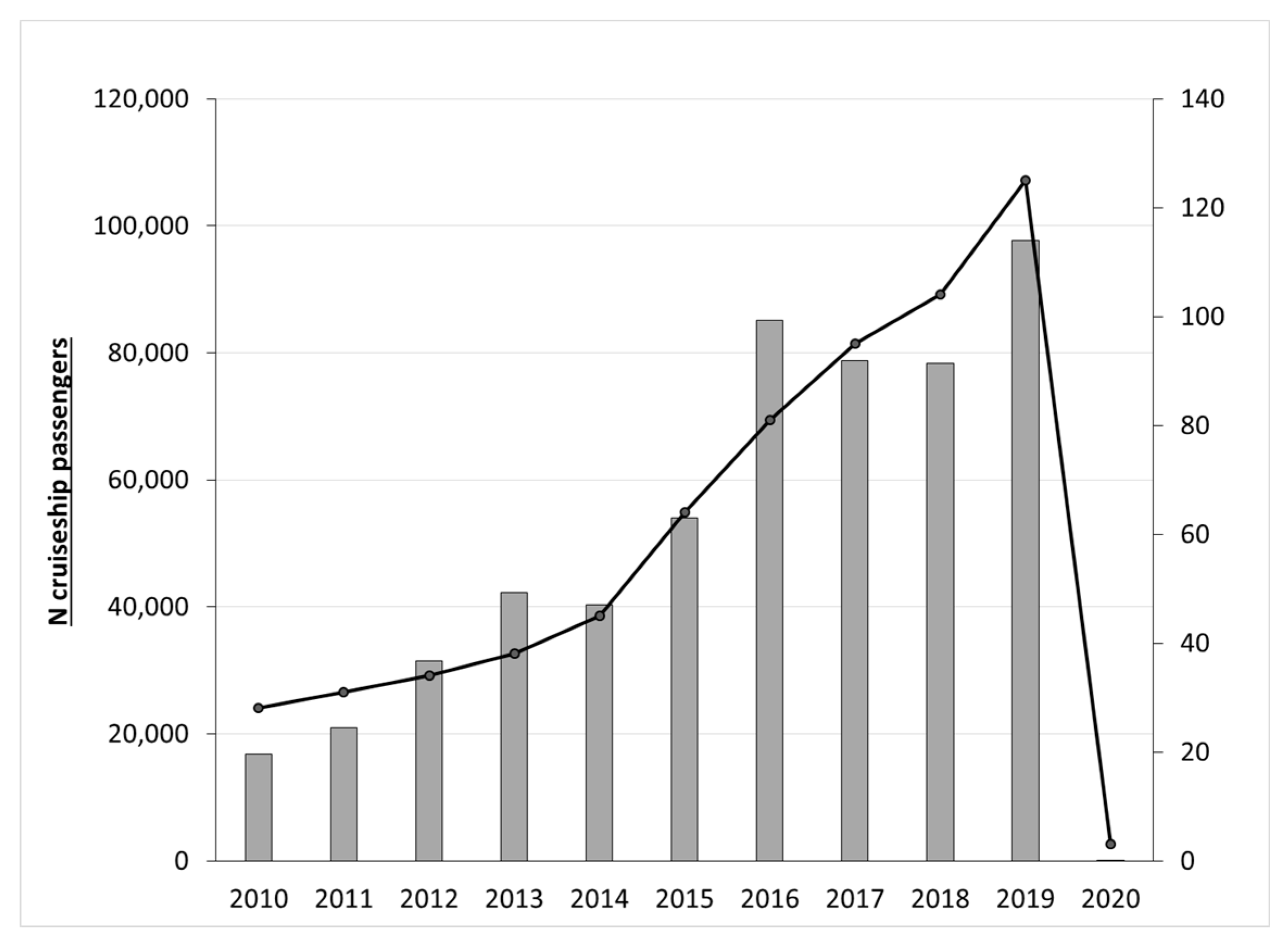

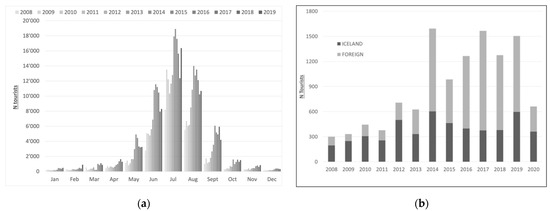

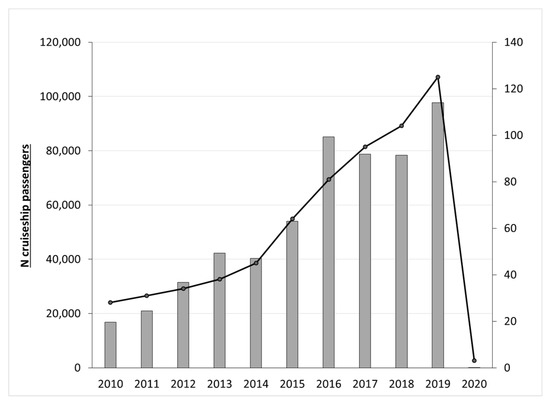

Tourism in Iceland grew rapidly from 2010–2018 (Figure 2b) [55]. In 2019, the strength of ISK led to a slight decline over the previous years, while in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic closed borders for much of the year. During this same period, tourism grew to represent over a third of Iceland’s export revenue, surpassing fishing and the metal industry. The Westfjords, one of the more remote and least populated in the country, is also one of the least visited regions in Iceland, with only 8–10% of tourists visiting Iceland coming to the region in recent years [55]. Whereas tourism has become much more common throughout the year in Iceland in general, tourism in the Westfjords remains very much a seasonal sector, with most tourists visiting in the summer months (Figure 5a). This rapid growth of cruise ship tourism in recent years (pre-pandemic) has further accentuated this aspect (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

(a) Tourism visits to the municipality of Ísafjörður by month: 2008–2019 [57]; (b) Origins of tourists visiting Ísafjörður municipality in the month of October: 2008–2020 [57].

Figure 6.

Cruise ship tourism in Ísafjörður: 2010–2020 [55,60].

The growth in cruise ship tourism has altered the face of tourism in the Westfjords. Unlike the regular tourists who rarely come to the area, Ísafjörður typically ranks as the third most popular port of call for cruise ships in Iceland (after Reykjavík and Akureyri). Thus, tourism pressure in the summer months has become quite high with the industry’s rapid growth in the area recently (Figure 6). The cruise ship season runs from mid-May until the end of September, with most ships coming in mid-summer [58]. On busy days, the number of cruise ship passengers can exceed the number of residents in town by a factor of two or three (population 2625 in 2018), which has led to conflicts between residents and tourists [59].

During the month of October, the time of the case study program, tourism visitation is much lower, averaging around nine percent of the monthly summer tourists (not including cruise ship tourists) [55]. Prior to 2014, the number of Icelandic and foreign tourists visiting in October was similar (Figure 5b). Since then, foreign tourists have grown to dominate the limited October tourism numbers (prior to the COVID-19 pandemic). It is also a time of year without cruise ship visitation. However, unlike with Chamonix, there has been no formal push to spread tourism more evenly throughout the year, and thus one could question if October is an appropriate time to visit the area as an ETP. On the one hand, it represents income for an area increasingly accustomed to income from tourism, and with the lower numbers during this time of year, a group of 20 staying for several days can be important. At the same time, this time of year may also represent a much-needed break from the masses of summer tourists. In this type of situation, ETPs must have excellent relationships with their host communities and pay close attention to their potential impacts in this period. For my program, working with the local institution, as well as my experience in the area, have helped us walk this line.

The pandemic has shed light on a potentially different situation in the Westfjords. The representative here felt that ETPs could bring positive impacts for the community in that they offer opportunities for new interactions in the remote setting. The lack of visiting groups or groups that only visit online did not bring those same opportunities. It stands to reason that the economic losses could also be important if ETPs do not come, particularly ETPs that provide income outside of the summer tourist season. Nonetheless, the representative also pointed out that the lack of international travel is better for climate change and more sustainable from that perspective.

3.2. Partnerships for Education

Another important part of sustainable educational travel, relates to the role that partnerships play for the ETPs. In my personal assessment, the partnerships in these cases reflect what is called for in the literature reviewed above [2,15,18]: the organizations are rooted in their communities and are well-connected within them, this is an established, long-term working relationship that benefits both parties, and both parties work together to co-create the programs for the ETPs. It is also worth mentioning that neither is a for-profit institution, a concern Barkin [5] raises about partnerships involved in some short-term ETPs.

3.2.1. Chamonix-Mont Blanc

In Chamonix-Mont Blanc, the ETP works primarily with a non-profit research and education organization that has been active in the region for several decades. Its research programs focus on the ecology of Alpine ecosystems and the impacts of climate change, which dovetail well with the ETP’s focus on Alpine ecosystems. As a small organization, it is able to support a diverse range of research and citizen science projects due to the inclusion of student and community participants in collecting data. These long-term projects provide multiple learning experiences for the students: they interact with scientists in the field and see research happening in real-time, they are able to gain valuable field research experience themselves, and they have the added benefit of contributing to a real-world project. Additionally, it allows the ETP to track and share findings with new visits and groups. I work closely with the organization’s staff to develop the course’s curriculum and incorporate preparation for the field component into the portion of the course on campus. The organization’s local network and connections are invaluable for both trip logistics, such as identifying appropriate places to stay, particularly in an effort to avoid larger-scale accommodations that target mass tourism. They have also helped to identify additional activities for the group, such as working with a local community to map invasive plant species, a service project that used the students’ academic skills to meet a local need. The organization staff is responsible for billing my institution for the services they provide and thus are ensured fair compensation for their efforts, which in turn helps support their research and programs. Overall, the partnership has proved successful for both parties for the two courses we have carried out, with plans for more in the future.

The representative from the host organization reported that the pandemic has had multiple effects on their organization and its collaboration with ETPs and other educational groups. With respect to their activities, they had to move almost all of their activities outdoors (although admittedly, many of their activities were already outdoors) and spend more time managing groups and group sizes to ensure compliance with COVID-19 regulations. With respect to hosting ETPs, my colleague reported that only one (mine) of the five groups (coming from Europe or North America) scheduled to visit in 2020 was able to come. As most programs they host come in the summer, the global situation in spring 2020 had generally prevented long-term planning involving travel. Since the organization runs several research projects that rely on student participants to collect data, the loss of groups meant reduced data collection, which had implications for those projects. Further, the loss of groups meant a loss of opportunities to share their research and pilot new educational projects. It further represented a loss of income that helps support program development and grant proposals. If the pandemic continues to impact international travel, they expect to shift their focus to primarily local and regional groups.

One unexpected benefit for the partnership from the pandemic was the opportunity for my group and the staff of the host organization to interact after the group had returned home. As we had all gotten accustomed to using virtual meeting software during the pandemic, it was easy to include the hosts virtually for the students’ final research presentations back on campus. The research projects were based on activities the students had done on-site that staff from the host organization had mentored. Having the staff present for the final presentations was an excellent opportunity for all parties: the host staff got to see what the students did after their return, and the students got to present their work to a group of professionals in the field whom they knew. Both our partner and the students enjoyed this approach, and thus, it is something we plan to repeat in the future.

3.2.2. Westfjords

In the Westfjords, my courses have been working with a small, local public higher education institution with a record of hosting ETPs. The institution also hosts several master’s programs that examine various aspects of environmental management and community development and a distance learning center; as such, it has strong connections locally, regionally, and nationally. I have worked with the staff to help develop and refine the course’s curriculum and adapt to changes that occur from year to year. The university’s staff, local network, and physical infrastructure have been invaluable for the course and its activities. The staff helps me understand what makes sense in October, as well as helping me identify appropriate places to stay. Similar to the situation in Chamonix, the host institution bills my institution for the services they provide, helping ensure fair compensation for our partners.

With respect to the pandemic impacts our host institution has experienced in the Westfjords, they also report having seen a decrease in international groups visiting (they do not normally host domestic ones). As an institution of higher education, they do not have the same kind of research projects at the institutional level that the organization in Chamonix does. However, the regulations and general pandemic situation have reduced the opportunities for field visits due to closures or unwillingness of other partners to receive visitors. Nonetheless, their small size and remote location have allowed them to be in-person more frequently than other locations in the country. Groups that were able to come have profited from that aspect. As the regulations have changed frequently and quickly, the staff has seen an increase in the time spent adapting programs to new requirements. Similar to their counterpart in Chamonix, they too feel that the loss of groups represents a lost opportunity for new ideas and interactions.

3.3. Educational Opportunities

The framework presented above asked the question as to how educational activities can also support sustainability, not simply in terms of gains for students but also for the host destination. As I discuss below, both destinations in concert with the partnerships have permitted the inclusion of experiential educational activities that have contributed greatly to the quality of these programs that also allow benefits to accrue beyond students and in the host destination: through both citizen science (Chamonix) and research service-learning (Chamonix and Westfjords) approaches.

3.3.1. Chamonix-Mont Blanc

As I mentioned above, our partner organization runs multiple participatory research and citizen science programs to engage the student participants. To prepare the students, the pre-travel portion of the course teaches and reviews the ecological background relevant to the projects. Once on-site during the travel, the local scientists further review the projects and give an overview of the sampling techniques the students will be using. The projects have included vegetation surveys of long-term sampling plots, phenological surveys looking at fall leaf changes in trees, and camera trap photo identifications. Whereas the first project is limited to groups that the organization hosts, the latter two projects are larger-scale regional citizen science projects that anyone can participate in via the web. As mentioned above, citizen science can be an important part of science education as it involves students in the process of creating knowledge [25]. Interestingly, the representative from the host organization reported an unexpected benefit during the pandemic for their citizen science programs that do not require supervision (i.e., the phenological monitoring, which people do at home, and the camera trap photo identification, which is done via the web). Both saw a substantial increase in the number of participants during the lockdown periods. The question remains, however, whether these new participants would continue to engage in the long-term.

A new project in which the most recent group participated falls more under the research service-learning designation. Our host partnered the students with a project in a nearby community trying to manage several invasive plant species that have taken over different areas throughout the town. As invasive species are a topic covered in the course, the project fits nicely into the curriculum. The students worked in groups with community members to map the occurrence of the species within the community. Through this activity, students were able to experience firsthand how problematic invasive species can be and how communities can engage in their own research, as well as provide a service to a community in the host destination that was useful and requested. The representative pointed out that the loss of ETPs would hurt community organizations such as this one. Had we not been able to come, this project would have been delayed indefinitely.

3.3.2. Westfjords

In the Westfjords, the students on the ETP have always engaged in field research projects that they developed with me. A few years ago, we were able to shift to a model that is more akin to research service learning. A partner of the host institution who worked in the tourism sector was overseeing a project to improve and expand the existing hiking trail system in the region. However, the project had very little funding or staff and needed background research to help develop a funding proposal. The students again worked in groups to carry out field surveys of the existing and one proposed new trail, accompanied by a local volunteer or myself. They assessed trail quality, problem areas, and the need for additional infrastructure; in the case of the new trail, the students also mapped the proposed trail and assessed the sensitivity of the landscape within a GIS. The groups carried out the field research during the travel and then analyzed the data and wrote reports during the remainder of the semester. This project provided a needed service to a local community while giving the students valuable field experience and insights into environmental careers. Again, as mentioned above, if projects such as these rely on ETPs, the loss of such programs could have a negative impact on community groups.

4. Discussion

This paper has examined issues related to the effects ETPs have on the destinations that host them (i.e., partner organizations and the communities in general) and highlighted some practices that the author has developed over his years leading ETPs that strive to minimize negative impacts and increase positive ones. The observations are hopefully valuable to all who run and sponsor ETPs, but perhaps most so for programs focusing on sustainability-related topics since minimizing negative impacts is part and parcel of the sustainability discourse. The case studies used here demonstrate good partnerships and planning can help maintain the benefits of the experiential educational experience while working to respect the host destination.

One crucial part of the good ETP-host institution relationship, as discussed at the beginning of this paper, is that it provides benefits to both parties and that it is reciprocal [18,30,39]. In both case studies, the relationships benefit each side. The benefits for the ETP side are clear: students participate in an experiential education that engages them in a local setting. Our host partners benefit from participation in research programs, from the opportunity to try out new activities, and from the interactions with the students; the loss of these benefits was felt by both destinations during the pandemic and thus would be likely felt if the ETPs were lost due to other reasons. Further, with both sides co-creating the curriculum, the ETP’s academic goals thrive through leveraging the host institution’s resources. The collaborations can result in exciting new projects and activities, particularly as the partnership grows over time. Lastly, because the partner institutions are paid for their time at prices they set, the partnership is economically sustainable for the host institution.

Although impacts on the broader host communities are harder to gauge, ETPs likely have less of an impact in a destination with a large tourism economy that is active most of the year, such as Chamonix. In a smaller setting, such as the Westfjords, ETP impacts, both positive and negative, are much more likely to be felt. The approaches discussed above provide ways to make impacts positive and more widely distributed. To enhance the positive impacts, research service-learning experiences can provide ways that students can use their academic skills related to the course to assist the community in meeting needs that it identified and with which it requested help. This approach avoids putting unskilled students in situations in which they could cause more harm than good. Additionally, having well-connected local partner organizations helps identify local service providers and accommodations for the program so that more of the economic benefits from hosting the ETP stay in the host community. Finally, one of the host organization’s representatives suggested that a community might further benefit from good PR when the student participants return home and share their experiences with friends and family and encourage future visitation. Savvy use of social media can facilitate this aspect.

A negative impact that the literature cautions against is cultural invasion or a clash of cultures. Certainly, in these case studies, the destinations both have Western European cultures, which are similar to that of the ETP institution, so such problems are less likely than they might be for an ETP destination in the Global South. Nonetheless, we take steps to try to minimize potential problems. As I described earlier, the structure of Franklin’s Academic Travel program ensures students have six weeks of classes on campus before we travel to the host destination (similar to the “extended semester” model that Barkin recommended [2]). This allows us to discuss cultural differences and behavior expectations well in advance of the travel itself. Further, both host organizations follow up with an on-site orientation to the program and the destination when we arrive. Interestingly, for the partner in the Westfjords, the interactions with the students also bring positive benefits to the community, benefits that were lost during the pandemic and would be lost if the ETPs were to change destinations or stop visiting altogether.

The COVID-19 pandemic provided an opportunity to understand the importance that ETPs hold for their host organizations, and the two partner organizations were affected differently. The research and education non-profit in Chamonix appeared to feel the loss of the ETPs more, as their participants and income from the programs are a larger part of their operations. Smaller providers that ETPs frequent may bear more of an eventual loss. In the Westfjords, hosting ETPs is just one aspect of our partner institution’s operations, and thus, they can probably weather the loss of ETPs better. However, the situation is likely reversed for the community. Given the low level of tourism for large parts of the year, ETPs that regularly come during those times can contribute important economic income to the area’s businesses. ETPs should be aware of the importance of their visits, particularly once they have become an established occurrence.

Finally, this comes to the last question from the framework in Table 1: how researchers can assess impacts to host destinations. This study took a qualitative approach primarily through its case studies, relying primarily on observations from the author and representatives from the host organizations. Relying on interviews with host organizations for this study worked, given the balanced and good working relationships between parties. Nonetheless, interviews with host or community partnerships can be fraught with challenges, particularly in situations where power dynamics or benefits from the partnership are heavily one-sided [61]. Other approaches in the studies reviewed above have used economic and GIS analyses, in addition to interviews, to get at potential and real impacts. Nonetheless, studies examining the full gamut of impacts of ETPs are on host destinations are lacking yet badly needed.

5. Conclusions

Ultimately, ETPs will never be able to be without any adverse impacts. Programs that cannot run without causing major adverse impacts to their host destination should stop and reassess their operations and choice of destination. On the other hand, minor, unavoidable impacts can perhaps be partially offset through quality service experiences and thoughtful planning. Further, formally and explicitly engaging students with these impacts can be an important part of the students’ education and preparation for life after university. If they go on to be repeat travelers, either as tourists or professional travelers, they will likely encounter similar issues and challenges. Time and effort spent modeling good practices and discussing and reflecting on all outcomes will help students gain the skills and perspectives they need to be more respectful travelers in the future.

Overall, ETPs need to focus more on their impacts in the host destinations to ensure that they are treating the host’s community, environment, and any partner organization respectfully and ethically. We need the same level of scholarship on these topics as we have on the educational benefits for students so that we can truly understand the impacts ETPs create and what to prioritize. Although this study has focused on relationships with partner institutions, stakeholders actively involved in the ETP, and the educational activities that support good, beneficial, and reciprocal relationships, it goes without saying the travel leader also should have had significant experiences in a destination before developing an ETP. This might include having lived, worked, or researched in the area, as well as learning/speaking the local language(s) and having insights to the local culture(s). If we fail to address these issues, we can harm the communities that graciously host us to provide valuable learning experiences for our students. We also lose the opportunity to show students the importance of these issues and fail to help them develop a mindset that eschews the exploitation of others.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Franklin does not have a formal IRB; however, I asked colleagues with IRB training from former institutions to examine my list of questions for the interviews.

Informed Consent Statement

I obtained consent from each interviewee prior to the interview.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this paper are available at the links provided in the references or are presented in the paper itself.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank his partners for both sharing their perspectives on the pandemic, as well as the successful collaborations that have made this paper possible. He also thanks P. Dasgupta, A. Hixson, and S. Sugiyama for their helpful input. Any remaining errors are his alone.

Conflicts of Interest

As mentioned in the paper, the author leads ETPs, including those presented in this paper, for his home institution.

Appendix A

The following is the list of questions used in the interviews with host institution representatives that took place in November 2020.

- How have the number of your educational programs been affected since COVID? Do you see a difference between domestic groups and international groups?

- What are the challenges you face during times of COVID, specifically with respect to field programs? (and citizen science programs—Chamonix only)

- How do you view the landscape of education programs changing during COVID?

- Do you think there might be some fundamental changes to the approach to teaching in a post-COVID world?

- How do you think the research will be impacted in the face of fewer student volunteers?

- How has COVID affected your willingness to collaborate with student groups/university groups?

- Do you think the student programs impacted the local communities economically and/or socially? Are they positive or negative? If positive, how will the crisis impact these changes?

References

- Long, J.; Vogelaar, A.; Hale, B.W. Toward sustainable educational travel. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkin, G. Undergraduate Research on Short-Term, Faculty-Led Study Abroad. Counc. Undergrad. Res. Q. 2016, 36, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gibson, H.J. Long-Term Impact of Study Abroad on Sustainability-Related Attitudes and Behaviors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.; Sahakyan, N.; Yong-Yi, D.; Magnan, S.S. The impact of study abroad on the global engagement of university graduates. Front. Interdiscip. J. Study Abroad 2014, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkin, G. Either Here or There: Short-Term Study Abroad and the Discourse of Going. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 2018, 49, 296–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, H.; Gibson, H.J. An investigation of experiential and transformative learning in study abroad programs. Front. Interdiscip. J. Study Abroad 2017, 29, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landon, A.; Woosnam, K.M.; Keith, S.; Tarrant, M.; Rubin, D.; Ling, S.T. Understanding and modifying beliefs about climate change through educational travel. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Jamieson-Drake, D. Predictors of study abroad intent, participation, and college outcomes. Res. High. Educ. 2015, 56, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoglu, B.; Ertuna, B.; Sasidharan, V. A referential methodology for education on sustainable tourism development. Sustainability 2014, 6, 5029–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paige, R.M.; Fry, G.W.; Stallman, E.M.; Josić, J.; Jon, J. Study abroad for global engagement: The long-term impact of mobility experiences. Intercult. Educ. 2009, 20, S29–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rexisen, R.J. The impact of study abroad on the development of pro-environmental attitudes. Int. J. Sustain. Educ. 2013, 9, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stoner, K.R.; Tarrant, M.A.; Perry, L.; Stoner, L.; Wearing, S.; Lyons, K. Global citizenship as a learning outcome of educational travel. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2014, 14, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, S.; Wearing, S.; Lyons, K.; Tarrant, M.; Landon, A. A rite of passage? Exploring youth transformation and global citizenry in the study abroad experience. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2017, 42, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, H.L.; Gibson, H.J.; Tarrant, M.A.; Perry, L.G.; Stoner, L. Transformational learning through study abroad: US students’ reflections on learning about sustainability in the South Pacific. Leis. Stud. 2016, 35, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, J.; Patel, M.; Johnson, D.K.; de la Rosa, C.L. The Impact of a Short-Term Study Abroad Program that Offers a Course-Based Undergraduate Research Experience and Conservation Activities. Front. Interdiscip. J. Study Abroad 2018, 30, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.; Landon, A.; Tarrant, M.; Rubin, D. Sustainability Education and Environmental Worldviews: Shifting a Paradigm. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landon, A.C.; Tarrant, M.A.; Rubin, D.L.; Stoner, L. Beyond “Just Do It” Fostering Higher-Order Learning Outcomes in Short-Term Study Abroad. AERA Open 2017, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lutterman-Aguilar, A.; Gingerich, O. Experiential pedagogy for study abroad: Educating for global citizenship. Front. Interdiscip. J. Study Abroad 2002, 8, 41–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrant, M.A. A Conceptual Framework for Exploring the Role of Studies Abroad in Nurturing Global Citizenship. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2009, 14, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biber, D. Transformative learning curriculum for short-term study abroad trips. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2020, 21, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgo, C.A.; Ezell Sheets, J.K.; Pascarella, E.T. The link between high-impact practices and student learning: Some longitudinal evidence. High. Educ. 2015, 69, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, J.A.; Ahern-Dodson, J. Promoting Science Literacy Through Research Service-Learning—An Emerging Pedagogy With Significant Benefits for Students, Faculty, Universities, and Communities. J. Coll. Sci. Teach. 2010, 39, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, J.A.; Lowman, M.D. Promoting ecoliteracy through research service-learning and citizen science. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 11, 565–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauermann, H.; Vohland, K.; Antoniou, V.; Balázs, B.; Göbel, C.; Karatzas, K.; Mooney, P.; Perelló, J.; Ponti, M.; Samson, R. Citizen science and sustainability transitions. Res. Policy 2020, 49, 103978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R.R.; Urban, J.; Cavelier, D.; Cooper, C.B. The Tragedy of the Unexamined Cat: Why K–12 and University Education Are Still in the Dark Ages and How Citizen Science Allows for a Renaissance. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 2016, 17, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crall, A.W.; Jordan, R.; Holfelder, K.; Newman, G.J.; Graham, J.; Waller, D.M. The impacts of an invasive species citizen science training program on participant attitudes, behavior, and science literacy. Public Underst. Sci. 2013, 22, 745–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bela, G.; Peltola, T.; Young, J.C.; Balázs, B.; Arpin, I.; Pataki, G.; Hauck, J.; Kelemen, E.; Kopperoinen, L.; Van Herzele, A.; et al. Learning and the transformative potential of citizen science. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peter, M.; Diekötter, T.; Kremer, K. Participant outcomes of biodiversity citizen science projects: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dvorak, A.; Christiansen, L.; Fischer, N.L.; Underhill, J.B. A Necessary Partnership: Study Abroad and Sustainability in Higher Education. Front. Interdiscip. J. Study Abroad 2011, 21, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.A.; Banks, S.; Galiardi, S.; Koehn, J.; Schroeder, K. Community impacts of international service-learning and study abroad: An analysis of focus groups with program leaders. Partnersh. J. Serv. Learn. Civ. Engagem. 2011, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, K.; Wood, C.; Galiardi, S.; Koehn, J. First, do no harm: Ideas for mitigating negative community impacts of short-term study abroad. J. Geogr. 2009, 108, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larsen, M.A.; Searle, M. Host community voices and community experiences: Tanzanian perspectives on a teacher education international service-learning project. Partnersh. J. Serv. Learn. Civ. Engagem. 2016, 7, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ficarra, J. Producing the Global Classroom: Exploring the Impact of US Study Abroad on Host Communities in San Jose, Costa Rica and Florence, Italy. Ph.D. Thesis, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sherraden, M.; Bopp, A.; Lough, B.J. Students serving abroad: A framework for inquiry. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engagem. 2013, 17, 7–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, B.W. Understanding potential impacts from university-led educational travel. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D. Sustainable Tourism: Theory and Practice, 1st ed.; Butterworth Heinemann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, K.; Clark, L.; Hammersley, L.A.; Baker, M.; Rawlings-Sanaei, F.; D’ath, E. Unintended outcomes of university-community partnerships: Building organizational capacity with PACE International partners. Asia-Pac. J. Coop. Educ. 2015, 16, 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- Tompson, G.H.J.; Beekman, R.; Tompson, H.B.; Kolbe, P.T. Doing More than Learning: What Do Students Contribute during a Study Abroad Experience? J. High. Educ. Theory Pract. 2013, 13, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, L.; Schroeder, K.; Wood, C. A Paradigm Shift in International Service-Learning: The Imperative for Reciprocal Learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogford, E.; Lyons, C.J. The impacts of international service learning on a host community in Kenya: Host student perspectives related to global citizenship and relative deprivation. Front. Interdiscip. J. Study Abroad 2019, 31, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, B.W. Wisdom for traveling far: Making educational travel sustainable. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larsen, M.A. International service learning: Engaging host communities—Introduction. In International Service Learning: Engaging Host Communities; Larsen, M.A., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 3–18. ISBN 1317554582. [Google Scholar]

- Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques Statisques Locales. Available online: https://statistiques-locales.insee.fr/ (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- CREA Mont-Blanc Le Massif du Mont-Blanc|ATLAS Mont-Blanc. Available online: https://www.atlasmontblanc.org/massif-mont-blanc (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Hale, T.; Angrist, N.; Goldszmidt, R.; Kira, B.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; Webster, S.; Cameron-Blake, E.; Hallas, L.; Majumdar, S.; et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Our World in Data COVID-19 Stringency Index. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/covid-stringency-index (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Eurostat GISCO: Geographical Information and Maps. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/gisco/geodata/reference-data (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- BAFU Hydrologie-Federal Office of the Environment Generalised Background Map for the Representation of Hydrological Data. Available online: https://geocat.ch (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- National Land Survey of Iceland Niðurhal. Available online: https://www.lmi.is/is/landupplysingar/gagnagrunnar/nidurhal (accessed on 13 February 2017).

- Guðjónsdóttir, S. Iceland in Figures 2018; Statistics Iceland: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2018; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Visit Westfjords. The Westfjords; Westfjords Tourist Information: Isafjörður, Iceland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Macrotrends France Tourism Statistics 1995–2021. Available online: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/FRA/france/tourism-statistics (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- L’Agence Savoie Mont Blanc. Les Chiffres Clés: Savoie, Haute-Savoie, Édition 2021; L’Agence Savoie Mont Blanc: Annecy, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- L’Agence Savoie Mont Blanc La Fréquentation des Sites Touristiques de Savoie Mont Blanc. Available online: https://pro.savoie-mont-blanc.com/Observatoire/Nos-donnees-brutes/Frequentation-des-sites (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Óladóttir, O.Þ. Ferðaþjónusta í Tölum. Available online: https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/is/tolur-og-utgafur/ferdtjonusta-i-tolum (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Pôle Animation Territoriale et Développement Durable. Rapport Développement Durable 2019: Des. Actions Pour Demain; Pôle Animation Territoriale et Développement Durable: Annecy, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hagstofa Íslands Gistinætur og Gestakomur á Öllum Tegundum Gististaða Eftir Sveitarfélögum 2008–2020. Available online: https://px.hagstofa.is/pxis/pxweb/is/Atvinnuvegir/Atvinnuvegir__ferdathjonusta__Gisting__3_allartegundirgististada/SAM01603.px (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Ísafjarðarbæ Skemmtiferðaskip. Available online: https://www.isafjordur.is/is/thjonusta/samgongur/hafnir/skemmtiferdaskip (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Sverrisdóttir, K. Untitled presentation. In Proceedings of the Ráðstefna um Skemmtiferðaskip 2017, University Center of the Westfjords, Isafjörður, Iceland, 4 April 2017; Available online: https://www.uw.is/radstefnur/glaerukynningar_2017/ (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Ferðamálastofa (Iceland Tourist Board) Komur Skemmtiferðaskipa á Íslandi. Available online: https://www.maelabordferdathjonustunnar.is/is/farthegar/skemmtiferdaskip (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Larkin, A.; Larsen, M.; MacDonald, K.; Smaller, H. Epistemological, methodological and theoretical challenges of carrying out ISL research involving host communities: A conversation. In International Service Learning: Engaging Host Communities; Larsen, M.A., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 19–31. ISBN 1317554582. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).