1. Introduction

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted by the United Nations [

1] Member States in 2015, have increasingly focused on entrepreneurial learning interventions to support ambition in young people to start their own businesses and generate their own employment opportunities (SDG4.4 and SDG8.3). Furthermore, the European Union (EU) considers entrepreneurial skills to be an essential factor in creating social and economic sustainability. Entrepreneurship education (EE) seeks to empower individuals with sufficient formal education and training to support entrepreneurial behavior and thinking. According to European policy documents [

2], we need skills and competences that support personal development, social inclusion, active citizenship, and employment. The key competences believed to enhance human capital, welfare, and competitiveness include literacy, numeracy, science, and foreign languages as well as transversal skills, e.g., digital competences, entrepreneurship, critical thinking, and problem solving [

3]. Entrepreneurship education can cultivate such competences throughout life in different contexts and for different purposes, such as using these competences to create entrepreneurial actions impacting on sustainable development goals (e.g., [

1,

4], in particular SDG4.7). Furthermore, entrepreneurial culture enables, e.g., SMEs to turn environmental challenges into opportunities [

5].

The European Entrepreneurship Competence Framework (EntreComp) is one of the EU’s responses to support common understanding and widespread integration of entrepreneurship, within and across education systems, promoting entrepreneurial learning towards social, cultural, or financial value creation. EntreComp is suggested as a tool for supporting development of the entrepreneurial capacities of European citizens and organizations by establishing a consistent reference point to support development of shared concepts of entrepreneurship competences, goal setting, and evaluation. Previous studies on EntreComp indicate that it is possible to build education programs on EntreComp [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] by using the framework as a basis for curricula development and learning activities. As Bacigalupo et al. [

3] stress, the use of the framework is claimed to foster entrepreneurship as a transversal and holistic competence, applicable to diverse purposes and contexts. The framework can also be used to describe and differentiate outcomes and attainment in the assessment of entrepreneurial competences [

3]. For example, in Finland EntreComp has been adapted into higher education teaching practices with good results. Recent empirical evidence indicates that the EntreComp competences are attributes of success aligned with the expectations of the future of working life, and are therefore meaningful for transforming education [

11].

Although entrepreneurship education appears to be gaining ground [

12], with widespread policy recognition of the need for educational reforms, educators and other education professionals have struggled to identify the content and methods with which to implement EE. It has also been acknowledged that educators’ learning processes have been missing from education policy implementation [

13]). However, consideration of educators’ reflections and learning processes are a crucial feature of successful educational reforms, such as the implementation of the EU strategies and frameworks that form a vision for the future of education. Additionally, motivation for change, sufficient substance knowledge, and understanding of how to implement these reforms in practice are essential [

14,

15]. This is also supported by Kelchtermans’ [

16] claim that educators’ sense of identity and their individual roles are key drivers of active engagement with educational review and renewal processes. Strengthening this, the Eurydice report [

12] states that educators’ attitudes and behaviors in EE may be even more important than substance knowledge.

Previous studies imply that the successful development of entrepreneurship education by engaging educators is a complex issue. In response, many scholars have introduced new approaches to widen the discussion using learning communities [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] and extending resource bases (e.g., society) for EE activities [

20,

22]. These approaches offer new possibilities for learners to gain experiences and insight through a participatory approach, which involves, e.g., policy-makers, representatives from private and public sectors, and parents [

13]. To cultivate a supportive ecosystem for EE, teachers, educators, policy-makers and communities may need to collaboratively reconsider their values and assumptions about school and education [

23,

24]. As Perrotta [

25] argues, educational cultures, policies, rationality, and emotional dimensions have high significance when adopting new approaches to education. This complexity is also highlighted in curriculum reform research: promoting an enterprising culture through curriculum reform requires meaningful, well-designed partnerships, securing wide participation of internal and external stakeholders [

26]. Such partnerships need to take into account local curricula, specific characteristics of different communities, and a focus on practice-oriented reforms [

23,

26].

However, there can be a significant gap between policy document recommendations and the design and implementation of entrepreneurship education in practice. In this paper, we anticipate that the development of entrepreneurial competences, driven by EU policies, requires the engagement and involvement of the whole learning community, acting as co-creators in the policy implementation through practice-oriented reforms. This approach is also highlighted by the chosen case study of the EntreComp framework. Therefore, this study investigates how the EntreComp framework has been implemented in transnational education contexts, looking particularly at how EntreComp guides the creation of a future vision for integrating entrepreneurship education to educational practices. Empirical data was collected from educators to examine how it is implemented and understood in practice: how can the framework motivate educational change and reform? By addressing these issues, we highlight how a policy-driven entrepreneurial competence framework can provoke, support, and drive educational change in Europe, and describe what kind of activities might further strengthen entrepreneurial competences and the sustainability of education in practice. Our case study also opens up opportunities for further research. For example, Cohen et al. [

27] argue the generalizability of such single experiments (e.g., case and pilot studies) can be further extended through replication or multiple experiment strategies, allowing single case studies to contribute to the development of a growing pool of data. In this context, we may consider case studies methodologically, both quantitative and qualitative, that we adapt for our purpose in studying the case of EntreComp.

A case study of the EntreComp360 project [

28] allowed the gathering of a wide trans-national data set. The project’s main goal was to develop opportunities to connect the wider community and provide guidance and resources to support those who are inspired by, or are already using, EntreComp across lifelong learning. To achieve this, it was essential to obtain an overview of European entrepreneurship education and how EntreComp is, and might be, integrated into it. Therefore, the EntreComp online survey was issued in 2020 targeting policymakers, lifelong learning organizations, educators, and other stakeholders. A comparative approach reveals: what are the learning communities’ key reflections and learning processes related to development of entrepreneurial competences? What is their vision for the future implementation of EntreComp? What is their motivation for change? How do they perceive and utilize EntreComp? Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected as part of the study. In total, there were 348 respondents from 47 countries. The country comparison is shown between the U.K., Finland, Spain, Germany, Italy, and Iceland to identify varying levels of integration of the framework in different national contexts.

The paper is structured as follows: firstly, we highlight the key points of the theoretical debate around EU policies driving entrepreneurship education and learning communities to create a framework for analysis by adapting the Shulman and Shulman framework [

14]. Secondly, we present the case of EntreComp, methodological choices, and data collection methods. Thirdly, we summarize the key results from the survey. Fourthly, we summarize the results gained in terms of what gaps can be identified, and what leverage is needed to support coherent educational reform to promote entrepreneurial competencies across Europe. Finally, we conclude that a lack of shared vision, motivation, practices, and understanding of entrepreneurship education can hinder the effective implementation of the framework. We propose further research on the integration of individual and community learning processes into the designing of the policy tools.

4. Results

4.1. Background Variables

A country comparison was realized between the U.K., Finland, Spain, Germany, Italy, and Iceland. First, we present the respondents’ job descriptions. One respondent may be involved in several fields, so the comparison of different job fields is not possible.

In

Figure 4 it can be seen that the education sector is strongly represented among the respondents. Many of them (n = 155) work in the field of higher education, adult education or adult inclusion (n = 114), vocational education and training (n = 112), non-formal youth education (n = 105), and start-up or business growth support (n =104). Only 15 respondents worked in the field of human resources. There were 35 respondents who work in unspecified fields. Next, we explain respondents’ understandings of EntreComp while highlighting country-specific differences—what they know about EntreComp in general, and how it relates to their work.

4.2. What Is the Understanding of EntreComp?

Almost half of all the respondents, 49.1 % (n = 171), were familiar with the EntreComp framework, 21.3% (n = 74) had heard something about it, and 29.3% (n = 102) of the respondents had not heard about EntreComp at all. One respondent did not answer. In the comparison of the six countries related to the question, ‘Are you familiar with EntreComp?’, the differences between countries were statistically significant (

p-value = 2.187 × 10

−11). The significance of the comparisons was obtained using the Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test.

Table 1 shows that in the U.K, (67.3%), Spain (63.9%), and Italy (76.7%), most of the respondents were familiar with EntreComp. On the other hand, in Germany (65.7%) and Iceland (70.4%), most of the respondents had not heard about EntreComp.

In the quantitative question ‘EntreComp is about promoting entrepreneurial learning. How much does the concept of entrepreneurial learning link to your work?’: 12.6% (n = 44) of all the respondents argued that ‘This is the main theme of my work’; 32.8% (n = 114) ‘Plays a big part in my work’; 35.1% (n = 122) ‘Relevant and included in my work to some extent’; 12.4% (n = 43) ‘Relevant but not (yet) included in my work’; and 2.3% (n = 8) ‘Not relevant to my work’. 17 did not answer.

When comparing the six countries, the comparison is statistically significant with

p-value = 4.32 × 10

−6 (

Table 2). In Finland, Germany, and Spain, most of the respondents answered that the quantitative question, ‘How much does the concept of entrepreneurial learning link to your work?’, is relevant and included in their work to some extent. In the U.K. and Italy most of the respondents answered that it plays a big part in their work. In Iceland most of the respondents answered that it is relevant and included in their work to some extent. It can be concluded that entrepreneurial learning does link to many respondents’ work. In the U.K. almost one third thought that it is the main theme of their work.

A majority of respondents, 61.5% (n = 214), answered ‘Yes’ to the quantitative question ‘Does your work link to some or all of the competences highlighted in EntreComp’, 29.9% (n = 104); ‘Partially—in some ways’, 2.3% (n = 8); ‘Not yet, but interested’, 0.1% (n = 3); ‘No’ and 5.5% did not answer (n = 19).

The results of the comparison between countries were parallel to the previous ones. Most of the respondents in Germany and Iceland answered that their work links partially to some or all of the competences highlighted in EntreComp (

Table 3). In Finland, Italy, Spain, and the U.K. the most common answer was that their work links to some or all of the competences highlighted in EntreComp. Altogether, it can be seen that almost all of the respondents’ work links to the competences highlighted in EntreComp in some ways.

In the last question (quantitative), ‘If entrepreneurial learning is not in the focus of your activities, are there other learning activities related to helping people such as those which allow young people or adults to transform ideas and opportunities, by mobilizing resources, into action?’ 48.3% (n = 168) of all the respondents answered ‘Yes’; 26.4% (n = 92) ‘Partially—in some ways’; 8.0% (n = 28) ‘Not yet, but interested’; 5.7% (n = 20) ‘No’; and 11.5% (n = 40) did not answer. The differences in comparison of the six countries was not statistically significant (

p = 0.0842) (

Table 4.).

Next, we will present the results of the research based on the theorical frame (vision, motivation, practice, and understanding).

4.3. What Is the Motivation for Using EntreComp?

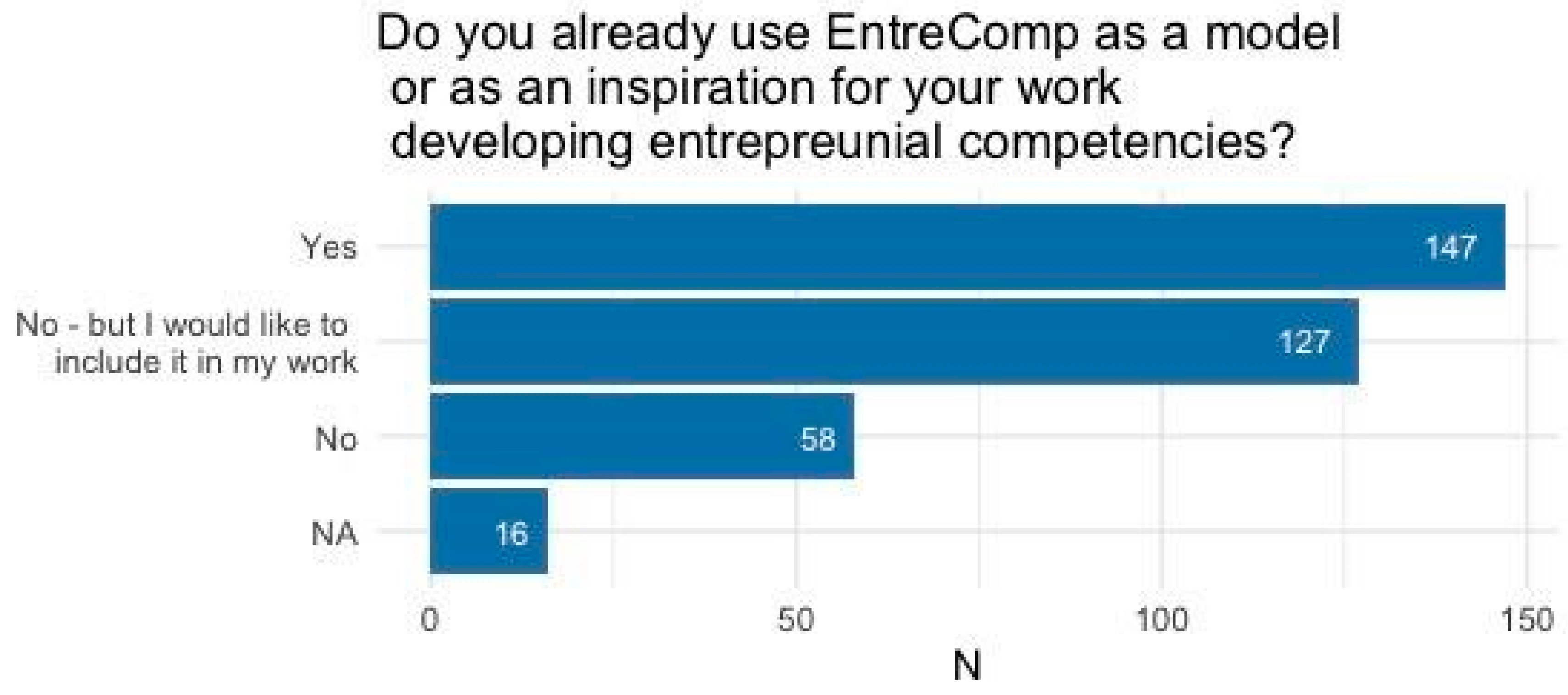

In the quantitative question, ‘Do you already use EntreComp as a model or as inspiration for your work on developing entrepreneurial competences?’,’ one could answer ‘Yes’, ‘No, but I would like to include it in my work’, or ‘No’. Some respondents omitted this question. The frequencies are described as a bar plot in

Figure 5. From the figure we see, for example, that slightly less than half (ca. 42%) of the respondents are developing entrepreneurial competences by using the EntreComp framework.

The comparison of the six countries shows (

Table 5) that most respondents in Iceland (57.7%) did not use EntreComp as a model/inspiration for their work on developing entrepreneurial competences, but they would like to. In Finland, Italy, Spain, and the U.K. the vast majority of respondents already use EntreComp as a model/inspiration for their work on developing entrepreneurial competences. In Germany, most respondents (42.4%) answered no. The comparison is statistically significant (

p = 2.016 × 10

−7).

In the quantitative question, ‘What would encourage you to become part of our EntreComp community?’, one respondent may provide several answers. The choices were ‘Sharing case studies or practices linked to my work’ (n = 180); ‘Contribute to research on ways to develop this work further at national/EU level—inform the next steps development of EntreComp’ (n = 165); ‘Putting me and/or my organization on the global map of EntreComp users’ (n = 163); ‘Access to professional development via online training or MOOCs’ (n = 136); ‘Becoming recognized as an EntreComp ambassador’ (n = 115); ‘Profiling and sharing my work through articles, blog posts or webinars’ (n = 113); and ‘Other (please specify)’ (n = 26). The frequencies of each answer are in parentheses after the answer alternative.

Answers to the question ‘What are the best ways to connect you to an online EntreComp community?’ are plotted as bars in

Figure 6. The question includes quantitative responses and a qualitative response in the option ‘Other’. Thus, we may conclude that LinkedIn and Facebook are the best platforms to build online connections with future community partners.

4.4. How Is EntreComp Implemented in Practice?

Because our study specifically sought to identify the factors that may make it challenging to implement EntreComp in order to create, e.g., future practices of EntreComp, we focused our questions primarily on these challenges rather than opportunities or other aspects. Therefore, our results are highlighted with an emphasis on the critical entry angle.

Implementation of the EntreComp framework was reported to include some challenges. Respondents find it time-consuming, difficult to understand, and the lack of language selection is problematic. Respondents already using EntreComp use it in all five areas (to mobilize, to create value, to implement, to assess, and to recognize), but mostly ‘TO MOBILIZE—raise awareness and understanding of these competences’ (n = 63) and ‘TO MOBILIZE—inspire or engage new people or organizations into entrepreneurial learning’ (n = 60). Again, it was possible to have several answers to the same (quantitative) question.

In an open-ended response question, 40 respondents had found, or were aware of, barriers that might prevent them or others from using EntreComp. For six respondents, language hindered use of the EntreComp framework. Two of the six respondents found the language options too limited, whereas, one respondent thought that the nuances in meaning of different languages makes translation challenging. Two respondents found time consumption to be a barrier and two respondents found the framework difficult to understand. Furthermore, four respondents faced unspecified barriers and three respondents found the framework to be difficult to use: e.g., one respondent described the appendix consisting of the list of skills to be difficult to use.

In another open-ended response question, 40 respondents expressed concerns about using EntreComp, with four respondents finding it too vast, and two respondents finding that they did not fully understand it. It was suggested to try to simplify it and to have a ‘use directly tool’, as the framework was seen to be rather theoretical. In addition, measuring the impact of entrepreneurial learning was considered to be difficult. There were also concerns about translating the framework into non-Western cultural contexts.

4.5. How the Vision for the Future Is Developed by Using EntreComp?

Of the 70 responses to the open-ended question, ‘What is your vision for using EntreComp?’, 10 respondents reported their visions relating to young people recognizing their own entrepreneurial skills, with 22 respondents highlighting application of the framework to different areas of life. Seven respondents’ visions emphasized the possibility of sharing good practices, consulting, and networking.

In the quantitative question, ‘How can we help you?’, presenting practical examples of how to support respondents to include EntreComp in their area of work, respondents may select more than one response. The choices were: ‘Resources that explain the value of entrepreneurial competences’, (n = 150); ‘Help to mobilize others on the relevance of EntreComp in my area of work’, (n = 75); ‘Practical examples of how to include EntreComp in my area of work’, (n = 203); ‘Online training on EntreComp in my area of work’, (n = 141); ‘Demonstrating the value of entrepreneurial learning’, (n = 136); ‘Being part of a community of people interested in developing and using EntreComp or entrepreneurial competences’, (n = 169); ‘High profile recognition for using EntreComp at individual or organizational level’, (n = 97); ‘Partner searching/matching to develop new tools or projects based on EntreComp/entrepreneurial competences’, (n = 155); ‘Understanding how to evaluate learning or working performance related to EntreComp competences’, (n = 152); ‘Having guidance on how to assess progress in the EntreComp competences’, (n = 142); and ‘Other’, (n = 20).

There were a total of 112 responses to the open-ended question: ‘This online community is about making EntreComp more easy-to-understand and easy to use. Do you have any suggestions?’. 15 respondents suggested using practical cases and examples to realistically implement the concept behind the model. Five respondents recommended that the model should be available in languages other than English, also reflecting non-European cultures. Four people said that instructional videos would be valuable. Twelve respondents suggested an online forum or Skype/Teams meetings to promote better understanding and use of EntreComp. Two respondents suggested face-to-face meetings and two suggested that the terminology should be tailored to target specific groups.

In an open-ended question concerning good practices, 49 respondents had found or were aware of successes or good practices that would encourage others to use EntreComp: 15 responded ‘No’; 284 did not respond at all; and 14 respondents answered ‘Yes’ without giving examples. Nine respondents reported using EntreComp to teach different skills in different practices. For example, they had had project-based approaches, workshops, and ‘normal’ classes online. The target groups mentioned ranged from young children to young apprentices, university students, and the elderly.

5. Discussion

The aims of the recent EU policy documents (e.g., [

2]) to foster entrepreneurial skills can be clearly seen within many EU-funded project initiatives, such as the development of the EntreComp framework. Even though fostering entrepreneurial skills is recognized to be globally important (e.g., UN SDGs), the effective implementation, and translation into practice, of the education policy documents remains complex. Therefore, this paper focused on analyzing how a cross section of actors, using EntreComp as a European framework for entrepreneurial competences, see that entrepreneurial learning has been realized and could be further supported in transnational education contexts. The results from the online survey generated new knowledge on how the EntreComp framework can guide the collaborative creation of a future vision for education; how well it is recognized, implemented, and understood in practice; and how it motivates and supports realization of educational change, which emphasizes the value of entrepreneurial competencies. The aim was to reveal how EU policies can drive educational change in Europe illustrated by the case of EntreComp.

Our results reveal that overall awareness and understanding of entrepreneurial education are ‘improving’ compared with earlier works, in which similar kinds of research settings and data collection were used [

15,

26,

50]. According to those previous studies, there is a need for the development of all aspects in reflection: vision, motivation, practice, and understanding. However, these were not the results in our case study. It can be stated that the EntreComp framework driving entrepreneurial learning is relevant to most of the respondents’ work. Moreover, the majority of respondents are motivated to integrate EntreComp in their work. Therefore, we may conclude that EntreComp can work in practice to strengthen the entrepreneurial capacity of European citizens and organizations (e.g., [

3]). This is also supported by Dinning’s [

6] and Gerbutt et al.’s [

7]) previous studies on EntreComp and entrepreneurial competencies. However, there might be some sampling error, thus raising the concern of bias in the chosen data collection method. As an example, in some situations, responses came by EntreComp projects. In some cases, answers were collected randomly from the education sector, without any connection to EntreComp. Furthermore, the number of responses is still low to conclude, e.g., the European situation of implementing EntreComp in practice.

However, our study also stressed that the implementation of entrepreneurial education initiatives driven by international policy goals is challenging. For example, the respondents estimated that adapting the EntreComp framework is time-consuming and it is difficult to understand the framework conceptually. On a more practical level, the lack of widely available translations of EntreComp is problematic. Furthermore, the need for training and guidance is highlighted to promote effective implementation. The respondents that already use EntreComp in their work, use it in all five areas (to mobilize, to create value, to implement, to assess, and to recognize) but mostly ‘TO MOBILIZE—raise awareness and understanding of these competences’, and ‘TO MOBILIZE—inspire or engage new people or organizations into entrepreneurial learning’. These results imply that currently the implementation of EntreComp is mostly related to awareness-raising on entrepreneurial education and inspiring students, curricula developers and educators, and may indicate that EntreComp is at an early stage in the implementation journey.

These same aspects were highlighted in the answers in which respondents explain their future visions related to using the EntreComp framework. However, the descriptions of the respondents’ visions are relatively modest, e.g., none of them described any future changes (societal, economic, or environmental) that they would like to see resulting from entrepreneurial education. This challenge related to the lack of understanding of EE in general and is also recognized in many previous studies (e.g., [

15,

26]). This finding is supported by the results of the survey, which indicate that almost one third of the respondents would require more support to be able to better demonstrate the value added by EE. Therefore, the potential impact and benefits of entrepreneurship education still require more explicit articulation and promotion [

21,

26,

50,

51], as well as more solid theoretical underpinning [

13]. This need was also reflected by respondents who highlighted the importance of evaluating the outcomes and impacts of entrepreneurship education.

According to the results, they key factors motivating respondents to use the EntreComp framework include the following: being psychologically and socially part of the EntreComp learning community in which recognition and support of individual and community entrepreneurial initiatives and activities are highlighted as valuable to promotion of EntreComp. It is thus important to note that the learning processes of the developers of entrepreneurship education play an important role in making progress in educational reforms in practice (e.g., [

12,

16]). This downplays the role and effectiveness of the traditional education policymakers, such as the state, as primary drivers of educational progress (e.g., [

31]). Indeed, effective learning requires participation, e.g., feedback and encouragement (e.g., [

53]), which is also relevant for the future development of such competence frameworks. Thus, further studies are still needed on how both individual and community learning processes can be integrated into the designing of policy tools, e.g., frames and roadmaps, to support a more effective implementation of the EE-related reforms. However, we may say that our study contributes the theoretical discussion in the field of entrepreneurship education by integrating ‘the reflection process of learners’, borrowing mainly the significant outcomes and frameworks from curriculum and curriculum reform studies (e.g., [

14,

15,

26]) to widen and deepen the understanding of factors influencing on the successful education change.

The respondents also suggested that ideas and best practices, related to implementation of the EntreComp framework, should be shared with other developers, e.g., through case study presentations. This draws attention to effective communication mechanisms within and between different learning communities. As an example, by highlighting individual success stories, significant psychological support and encouragement can be provided, which, according to the survey results, is one of the key areas for future development of the EntreComp framework. This learning proceeds most effectively if it is accompanied by metacognitive awareness and analysis of one’s learning processes and is supported by membership in a learning community (e.g., [

17,

18,

19,

20,

54]).

Adapting the community learning approach might be beneficial for further enhancing students’ learning processes as well as to the learning processes of, e.g., educators, other practitioners, parents, policymakers, and stakeholders [

14,

23]. Respondents highlight the importance of ‘belonging and recognition’ throughout the survey. This implies that a reciprocal relationship between community-based learning practices and national and local public policies is needed for seamless enforcement of educational aims [

49]. From this perspective, the development of the learning communities in a transnational context should also be given more attention. The learning community can often only be perceived too narrowly, only relating to the physically close, e.g., regional, community. However, the learning communities have become global and they are not solely tied to certain locations and can be digital, particularly in the COVID era when interaction is increasingly online. As a result, these learning communities can be global in reach and involve actors working at all levels, e.g., educators, stakeholders, policymakers, students, and private sector partners. Therefore, further studies are needed on how to promote the psychosocial learning processes of international communities, e.g., through adapting new technologies?

This becomes apparent, especially when looking at country differences as revealed by the results. This raises questions of whether global entrepreneurial learning communities could be developed more effectively, despite the country divergence, across lifelong learning policy and practice? Based on the survey results, we were able to identify three progress scenarios related to the implementation of the EntreComp framework: (a) in the U.K. and Italy, most of the respondents answered that EntreComp already plays a big part in their work; (b) in Finland, Germany, and Spain, most of the respondents feel that EntreComp is relevant and included in their work to some extent; and (c) in Iceland the respondents think their work links partially to some or all of the competences highlighted in EntreComp. However, EntreComp is not greatly utilized in their practical work. Thinking about these three scenarios, it would be valuable to examine how different cultural paths and educational policy factors guide the implementation of similar frameworks on a national level. In this study, we were able to indicate country-specific differences, but not the reasons behind them. Indeed, studying educational reform is not a straightforward process: it involves developing understanding of different cultures, policies, rationality, and emotional dimensions, which play a high role when adopting new approaches to education (e.g., [

25]). Our findings might provide a new starting point for further investigation of future design and implementation of education policies; as a next step, we propose collecting a broader data set from a more comprehensive, global sample of respondents, which would further develop the understanding of how entrepreneurial education initiatives can be efficiently and effectively implemented in different regions, countries, and cultures.

Since, e.g., The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and The European Union promote entrepreneurial competencies as a means of supporting young people to innovate, start businesses and create jobs, and creating welfare and economic sustainability, we focused our study on this area. Therefore, we conclude that our findings support that our educational initiatives are on ‘the right track’. However, more research and practical implications are needed to promote a ‘real’ change in education. In this context, we highlight, e.g., communities’ reflection and learning processes, thus supporting the development of a concrete vision for a ‘better sustainable world’ and pedagogical and practical ideas to take into use.

6. Conclusions

This paper extensively focused on the development of entrepreneurship education at the European level by examining how the EntreComp framework can act as an engine for transnational policy implementation driving entrepreneurial competences. This is the first time an entrepreneurship education study has respondents from so many different countries (46). Such major international studies have previously been, e.g., global reviews of studies conducted on entrepreneurship education in teacher education (e.g., [

55]). Furthermore, previous country comparisons were limited to fewer countries (e.g., [

15]). In that regard, our findings provide new insights into the overall progress of entrepreneurship education in the European context. However, its key contribution is linked to previous entrepreneurship education research by integrating the Shulman and Shulman [

14], Seikkula-Leino [

26], and Seikkula-Leino et al. [

21,

50,

51], theoretical framework to other relevant studies [

26] and the conceptual EntreComp framework’s goals: mobilize, create value, implement, appraise or assess, and recognize [

3] as summarized in

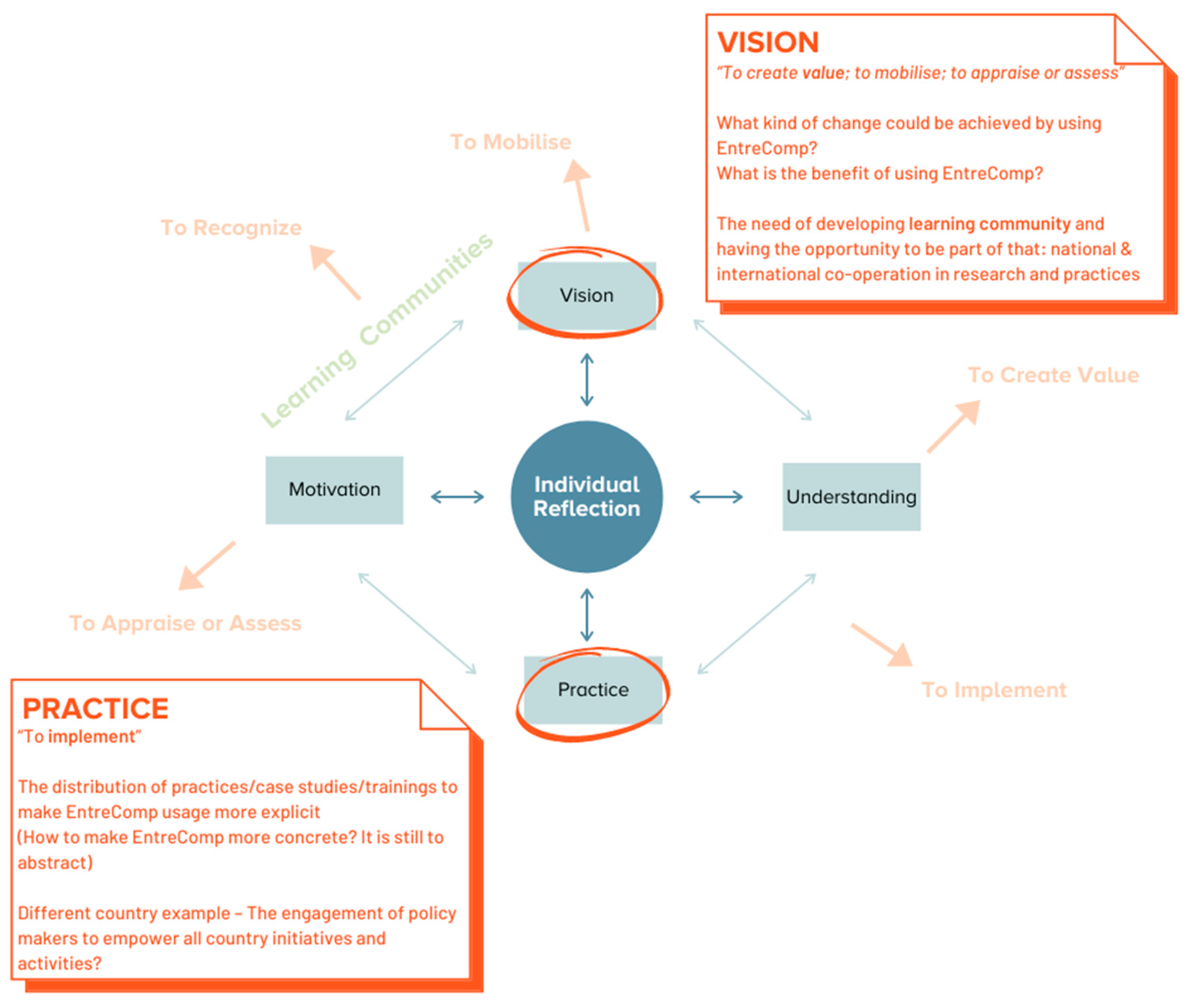

Figure 7.

The results highlight that the European competence framework EntreComp can increase motivation and understanding of entrepreneurship education in different trans-national contexts. Moreover, implementation has used all five goals. However, recognition of and support for learners’ (e.g., educators, other practitioners, policymakers, and stakeholders) roles within various learning communities, require further study. Educational practices (e.g., training, tools, and concepts) need to be developed to support the reflection and learning of learners to empower development of their vision and practices related to entrepreneurship education. Some practical examples to promote these are presented in

Figure 7 (e.g., case studies, other explicit models, country-specific examples, vision development through questions, and emphasis on learning communities). Further studies are still needed to identify the gaps in terms of required leverage towards coherent education change that promote entrepreneurial competences and the overall understanding of the EE within Europe. This would also provide new avenues to investigate how sustainable development could be promoted at the global, country, and local levels of education. This would also generate new knowledge on how to promote sustainable development within the private sector, for example in staff training.

Our case study has also broadened the general understanding of the way in which European strategies are guiding the development of entrepreneurial education. Overall, this kind of case study provides a suitable platform for investigating how these global goals can be detected in individual members’ attitudes and beliefs in different country contexts. As Cohen et al. [

27] argues, the generalizability of such single experiments (e.g., case and pilot studies) can be further extended through replication or multiple experiment strategies, which allows single case studies to contribute to the development of a growing pool of data for eventually achieving a wider generalizability of the key findings. Therefore, we suggest similar types of studies to be conducted to identify how policy goals can be successfully translated into frameworks, and what are the best practices for their successful implementation. Furthermore, a series of large-scale international studies could be useful in detecting how entrepreneurial education can be driven through policy framework, but also in demonstrating the added value of entrepreneurship education, as an example, by evaluation and case studies that would emphasize the learning and reflection processes within and across learning communities. This would also enable the design of more practical concepts and tools to support community learning processes to further strengthen entrepreneurial competences.

However, our research has certain limitations that need to be considered. For example, the number of respondents differed to some extent in different countries. Although the measure utilized previous bases, it could be further developed and validated based on the theoretical basis of Shulman and Shulman [

14], and Seikkula-Leino [

26], and Seikkula-Leino et al. [

21,

50,

51]. In addition, we could further develop the metrics to guide the target group to respond more precisely to issues related to sustainable development.

Undoubtedly, our research has significant value in finding out how, in practice, the European framework promotes practical change in teaching and learning. We highlight concrete proposals that could be considered in the future. In addition, we have opened up the theoretical discussion of entrepreneurship education in the direction of education science by utilizing the results obtained in this field and theoretical entry angles by stressing learning communities and their reflection. With this research, we contribute to the development of entrepreneurship education in many ways, both in theory and in practice, and globally, thus providing a sustainable ground for developing entrepreneurial society by education.