Abstract

Jamaica’s ageing population, high prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), and associated functional impairments suggest the need for a sustainable long-term care (LTC) system. This paper describes the current LTC system in Jamaica. A review of empirical and grey literature on LTC was supplemented with consultations and interviews and group discussions for knowledge exchange, impact and engagement events with stakeholders being conducted as part of a project on dementia care improvement. Four key findings emerged: (1) Jamaica’s LTC system depends substantially on informal care (both unpaid and paid); (2) there is a need for strategic coordination for LTC across the state, cross-ministerial, private, and volunteer sectors; (3) compulsory insurance and social protection schemes appear to exacerbate rather than narrow socioeconomic inequalities in LTC; and (4) there is a lack of systematic LTC data gathering and related information systems in both the private and public sector—for both institutional and community-based care. For LTC in Jamaica and the broader Caribbean region to be sustainable, more evidence-informed policies and practices that address inequalities in access to services, ability to pay for care, direct support from government, and the risk of needing LTC are needed.

1. Introduction

Jamaica is the largest English-speaking and third-largest island in the Caribbean, with an estimated total population of 2.96 million, and a rapidly ageing population, with the highest growth rate being among those 80 years and older [1,2,3]. Those 60 years and older are projected to constitute 18% of the population by 2050. The shift in Jamaica’s demographics and the projected continued increase of the older population, consistent with the wider Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region [4], signals the importance of robust and sustainable long-term care (LTC) services and systems. These are services and systems that meet the medical and non-medical needs of ageing persons who are not able to care for themselves for short (as in the case of those approaching death) or longer periods of time (as in the case of chronic illnesses or disability).

Though ageing does not necessarily equate to care dependence, there is an established relationship due to the decreased physical, mental, and psychological functioning associated with ageing. Population ageing is also a major contributor to the high prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) concentrated in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) such as Jamaica [5]. Further, in Jamaica and the wider LAC region, while life expectancy has increased, improvements in living standards and nutrition have not, contributing to the burden of NCDs [4].

There is a strong bi-directional relationship between NCDs and disability [6,7,8]. NCDs negatively impact mobility and can increase care dependency. On the other hand, persons with disabilities are especially vulnerable to NCDs because of underlying health conditions, being exposed to discriminatory practices, and an associated increased likelihood of living in poverty and other resource-constrained circumstances [7].

Within Jamaica, overall rates of NCDs (cardiovascular diseases, cancers, respiratory diseases, diabetes, and mental, neurological and substance use disorders) and their associated metabolic risk factors (hypertension, high cholesterol, obesity) and modifiable behavioural risk factors (unhealthy diets, physical inactivity) increased by over 50% between 2000 and 2018. Data from the national statistical institute, STATIN, suggest that over 25% of the population reported having at least one NCD, with the highest rates reported among women (29.7%) and persons 65 years and older (71.1%) (see Table 1, [9]). Many older persons in Jamaica require some form of LTC services [10]. Approximately 9% of Jamaicans 60 and older are living with dementia [11] and are, therefore, in need of LTC as these individuals have on average four comorbidities, while persons without dementia have two on average [12].

Table 1.

Prevalence (%) of NCDs by age group and sex from STATIN data in 2017.

Reports of the prevalence of persons living with disabilities in Jamaica vary widely from 3.3% to 13.6% [9,13,14,15], with the inconsistencies highlighting challenges with underreporting, lack of systematic data collection, and a lack of mandatory enrolment with the Jamaica Council for Persons with Disabilities (JCPD). According to Jamaica Survey of Living Conditions (JSLC), among those who reported a disability, physical disability was the most prevalent (34.5%) and disproportionately impacted those over 60 years [9]. These older individuals who often live with multimorbidities experience significant limitations in functioning and require assistance with activities such as eating, bathing, and moving around.

In the context of Jamaica’s ageing population, high prevalence of NCDs and related care dependence, and a significant segment of the population living with disabilities, this paper provides an overview of the LTC system in Jamaica. It also makes recommendations for a robust and sustainable model of LTC in the context of limited resources.

2. Materials and Methods

We completed targeted web and database searches of local, regional, and global empirical and grey literature on LTC between 2018 and 2021 using Google, Google Scholar, the West Indian Medical Journal, and the Caribbean Journal of Psychology. Search terms broadly included “long-term care in Jamaica” “caregiving in Jamaica” “caring for older persons”. Articles were also located based on hand searches of reference lists or from recommendations made by colleagues working within the area of caregiving, LTC, elder care (as it is typically referred to in Jamaica), and/or older persons. Informed by the literature review and consultations (described below), we graphically mapped Jamaica’s care system for older persons, using as a template a Malaysian case study [16], to provide an overview of the services available in the private and public sectors. The iterative development of the mapping of services and literature search enabled us to look at the balance between different types of care.

The literature search allowed for a critical analysis of the balance of informal versus formal LTC services in Jamaica, the level and types of LTC provision, and the degree of state participation. The data from the review were validated and supplemented by consultations with key stakeholders such as government officials, policymakers, non-governmental organizations, health and social care professionals operating in the private and public sector, and persons living with dementia and carers (also referred to as caregivers) of persons living with dementia. These stakeholder consultations occurred during: (a) theory of change workshops conducted in 2018 (n = 2) and 2019 (n = 1) (number of participants ranging between 20–55) aimed at addressing and prioritizing the needs of persons living with dementia and their caregivers (also referred to as carers in the local context and hereafter used interchangeably) through national policy and plans; (b) National Advisory Group meetings conducted between 2019 (n = 2) and 2020 (n = 3) (number of attendees ranging from 10–18); c) dementia-related knowledge exchange, impact, and engagement (KEIE) events and activities in 2018 (n = 3), 2019 (n = 19), and 2020 (n = 52). These efforts and related qualitative and quantitative data collections are part of a larger multinational dementia care improvement research project called STRiDE (Strengthening Responses to Dementia in Developing Countries) in which Jamaica is a participating nation. The project received ethical approval from the University of the West Indies Mona Campus Research Ethics Committee (project numbers ECP 122, 18/19; and ECP 46, 19/20) as well as by the London School of Economics.

3. Results

3.1. The Current Long-Term Care System for Older Persons in Jamaica

In Jamaica, as in many LMICs, there is no LTC insurance, LTC is gendered (mostly female), mostly informal (from family members and volunteers), and without financial or technical support from the state [5,17,18,19,20]. Further, women from lower income, often rural communities, who migrate to work as domestics in urban households, contribute to a large group of LTC providers because the supervision and care assistance they provide are technically unpaid; they are not paid for care work per se but for household work not-specific to the target care-recipient [17].

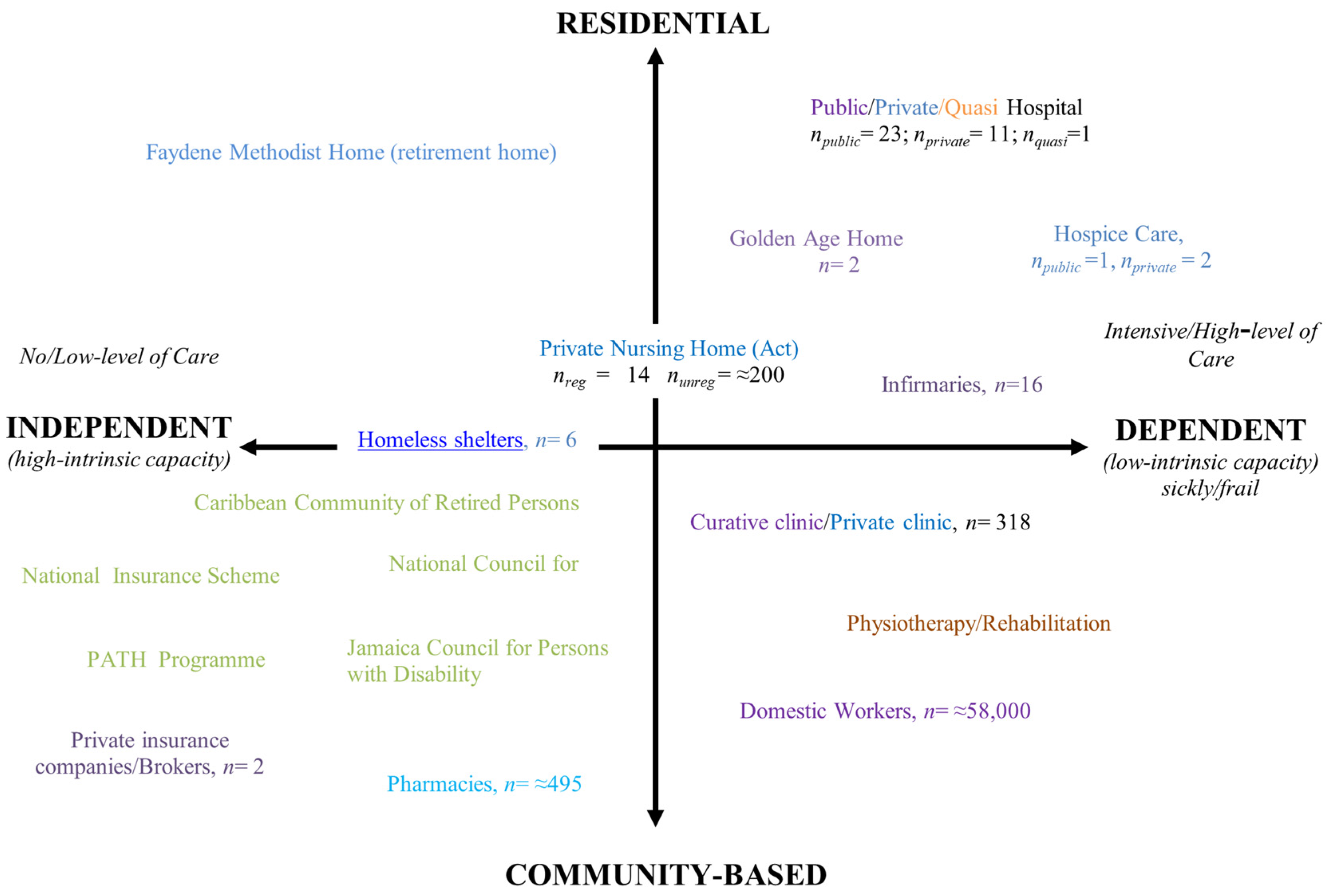

The graphical mapping of Jamaica’s care system for older persons (see Figure 1), provided an overview of the services available in the private and public sectors. Similar to the Malaysia mapping of services [16], the figure includes four quadrants depicting different types of LTC. In the Jamaica map the quadrants represent (1) independent residential facilities (top left); (2) dependent residential facilities (top right), including hospitals where older persons are cared for on a long-term basis or indefinitely; (3) community-based but independent care provisions (bottom left) and; (4) community-based but dependent care services or providers (bottom right).

Figure 1.

Jamaica’s Care System for Older Persons.

Similar to the Malaysia LTC mapping, the Jamaica mapping illustrated a high prevalence of unregulated care homes and a reliance on unregulated and untrained domestic workers. While Malaysia’s mapping presented a small number of day services, in Jamaica official documentation of such services (existence, operation, and service offerings) does not exist.

The Jamaica mapping also showed that while there are limited formal home and community-based LTC services such as respite care, home visits, meal delivery plans, and personal care services, when they do exist, they are often provided by NGOs and community-based places of worship. The formal care system for older persons in Jamaica include state-sponsored residential care and an increasing number of private nursing homes. For the private nursing homes, however, neither public nor private health insurance plans provide coverage specific to LTC. Furthermore, there is limited uptake of public or private health insurance—only 18% of the Jamaican population—a consistent figure over the past five years [9,21] and subscription to these plans is mostly from the middle and higher socioeconomic brackets.

3.2. Mapping Long-Term Care Provision in Jamaica

3.2.1. Informal Care in Jamaica

Similar to other work in this area [22], this paper differentiates unpaid (e.g., family members) from paid (e.g., those working in the informal economy who are paid in cash and/or without formal employment contracts) informal care.

Unpaid Care

While there is no census of the size, composition, and characteristics of providers or recipients of unpaid care in Jamaica, studies suggest that unpaid females and older persons perform LTC duties, regardless of household income [17,20].

One pilot time use survey (n = 541, 51% female) coded respondents’ activities using the (UN) trial classification of the System of National Accounts (SNA), an internationally accepted standard recommendations used to guide a compilation of measures of economic activity to inform national accounts [17]. It suggested that Jamaican women spent the equivalent of 40-h workweek on unpaid care work. Their daily average spent on unpaid work was three times (249 min) that of the time men spent (90 min). Further, the time women spent on unpaid care work increased as the number of children and older persons living in the household increased [17]. The study noted that the societal opportunity cost of providing unpaid care—predominantly borne by Jamaican women who had less access to resources and paid work than men did—included compromised health and wellbeing of other dependents in the household (i.e., children) [17].

Another study that examined caregiver burden among 180 caregivers of community dwelling older persons in Jamaica found that children and grandchildren of care recipients were three times more likely to report caregiver burden than formally employed caregivers [20]. The study noted that caregivers aged 45 to 65 years were 5.5 times more likely to report higher caregiver burden than those 44 years and younger. Furthermore, a greater proportion of spouses (46.2%) had mild to severe burden compared with siblings (33.3%), children (37.8%), neighbours (10.0%), and employees (14.6%) of the care recipient.

Consultations with unpaid caregivers of persons living with dementia and feedback from stakeholders during KEIE events support the findings from these local studies and offer additional insight relevant to caring for older adults, dementia specific LTC, and related costs. Consultations indicated that indirect costs that individuals and families shoulder (such as loss of income due to inability to participate regularly in the paid workforce, sick leave, and presenteeism) compound direct dementia care costs that often come from out-of-pocket payments (such as for medical practitioner/allied health professional visits, medication costs, specialized aid and equipment). Similar to what has been noted in other contexts [22,23], those who are able to pay for care have drawn from their individual and family resources (such as family members providing care, personal income, savings, and assets) and voluntary private insurance schemes. In the context of increasing research that speaks to the need for flexible working conditions, training and education interventions, psychological therapy, and formal care services for those in need [24], these indirect and direct costs speak to the financial unsustainability of these models of LTC care that do not address the socioeconomic impacts already occurring [23].

Domestic Workers

Another group crucial to the provision of informal care is domestic workers. Paid domestic workers often support unpaid carers from middle and higher socioeconomic strata. Employed by private households, these domestic workers do not typically receive formal contracts of employment and/or social protection entitlements from their employers. They are often paid via cash and at, or below, Jamaica’s minimum wage. Domestic workers may be full-time or live-in workers or may come to the household on a decided upon number of days per week (also referred to as a “day’s worker”). These arrangements often involve rural to urban migration where the domestic worker leaves the care of those in her own rural household to other women in those communities, and/or to young persons and/or children there.

On 29 July 2020, through personal communication with the authors, the President of the Jamaica Household Workers Association (JHWA) shared that of the estimated 58,000 domestic workers in Jamaica, approximately 6200 are represented by the association that focuses on lobbying, training on household management, and education on sexual harassment, violence against women, and mental health. To date, JHWA does not provide or facilitate training for its members on age- or illness-specific challenges such as dementia care and management.

3.2.2. Institutional LTC Services

Public (State-Sponsored) Residential Homes

As shown in Figure 1, Jamaica has 18 public residential homes and one public home for the terminally ill. Of the 18 facilities, 16 are referred to as infirmaries and provide housing and physical and mental health care at no cost to those 18 years and older who are unable to care for themselves. The remaining two facilities are referred to as Golden Age Homes, providing services similar to the infirmaries but designed for older indigent persons. With an estimated capacity of 1500 beds [25], the infirmaries can serve, at most, 0.005% of the over 60 years age group. A number of these public LTC facilities need major infrastructure overhauls as they have fallen into disrepair [26] (p. 6).

Private Residential Homes

In 2019, despite standard procedures and guidelines in place for nursing homes, only 14 (the majority [n = 7] located in Jamaica’s metropolitan area: Kingston and St Andrew) out of the over 200 private care homes were registered, indicating that the majority of homes in operation have not been inspected or assessed by local or national authorities [27,28]. While this less than 1% registration rate of private residential facilities within Jamaica is concerning, it also emphasizes the role that regulation of these private sector facilities can serve in mapping LTC providers nationwide and developing coordination for LTC needs. There is no publicly available geographic mapping of the 200-plus unregulated nursing homes and so their distribution throughout the island is unknown [29]. Given the lack of routine data gathering from and enforced regulation of these private facilities, the prevalence of older persons using these facilities is unknown. In general, the services offered by the privately-operated nursing and residential homes, as per the Standards and Regulation Division [27] at the Ministry of Health and Wellness (MOHW), include room and board, occupational therapy, physical therapy, religious services or transportation to same, recreational activities and outings, beauty therapy, transportation to medical appointments, medication procurement and service. Additional services include respite and day care services. The average cost of a nursing home in 2020 was J$72,500 (≈US$500) per month or J$870,000 (≈US$6000) per year. This cost represents almost three times the monthly minimum wage (J$28,000 [US$193]) or over 90% of the average household income (JD$79,910 [US$551]) [30].

Public/Private/Quasi Hospital

The Government of Jamaica operates one psychiatric care institution, Bellevue Hospital, which is the largest psychiatric facility in the English-speaking Caribbean. While the hospital is not intended as a LTC facility, the MOHW’s Auditor General’s Performance Audit Report [31] revealed that 85% of the patients at Bellevue did not require hospitalization for either acute or sub-acute presentations but were instead chronic patients. Many of these patients have social issues such as repeated admissions, dual diagnoses, have been abandoned by family and friends, or are persons who used to live on the street. The psychiatric hospital has functioned as a LTC facility for persons living with serious mental illnesses and in need of LTC. Similarly, public general hospital wards not intended for LTC are sometimes used for such, including by persons living with dementia who are abandoned by family members who may be unable to financially, physically, or emotionally care for their relative with LTC needs. On 7 May 2019, a parliamentary debate suggested that there were approximately 200 such cases.

Palliative care is provided by three hospice facilities: The Hope Institute Hospital, the Consie Walters Cancer Care Hospice, and the Brenda Stafford Village of Hope Hospice [32]. The University Hospital of the West Indies has a small in-patient palliative care service [32]. Hospice care in Jamaica primarily caters to cancer patients and those at the end of life; it infrequently accommodates those with LTC needs related to other NCDs such as cognitive impairment and dementia or other disabilities.

3.2.3. Community-Based LTC Services

Community-based LTC services such as respite care, home visits, meal delivery plans, and personal care services in Jamaica are provided mostly by not-for-profits, charities, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), which focus on creating social impact. Volunteers, especially individuals affiliated with churches and faith-based organisations, often provide unpaid assistance. Home visits by medical and allied health professionals are options for mostly the middle and upper socioeconomic groups. COVID has also accelerated the normalizing of tele- and virtual health care options for persons especially from these socioeconomic strata.

Churches and Faith-Based Organisations

Consultations and KEIE events elucidated the role of places of worship and faith-based organisations as central providers of community-based LTC services [33]. They provide multiple types of support, including but not limited to companionship, help with errands, meals provision, spiritual support and, to a lesser extent, provision of respite care either through sponsoring a nursing aide or offering their own time for the family-carer to leave the home for some time away. Unless operating public schools, for which they receive funding from the government, their funding comes from income generated through their operations of private schools and hospitals and through charitable donations.

Non-Governmental Organisations

NGOs in Jamaica also provide community based LTC through volunteering time and/or with financial or food/toiletries packages. They work closely with and often through ministries and departments, such as the Ministry of Labour and Social Security’s (MLSS) National Council for Senior Citizens and the JCPD, to offer personal care, social services, and welfare programmes. NGOs such as the Caribbean Community for Retired Persons (CCRP) offer activities for socialization, develop and implement programming for older persons, and do advocacy on behalf of their needs. Global organisations of volunteers such as Kiwanis, Rotary and Lions Clubs and their associated foundations have Jamaica chapters and contribute to LTC with their time, labour, and fund-raising. Other volunteer groups and individuals offer social support specific to carers of persons living with dementia (e.g., local and diaspora Facebook Dementia Support Groups, Alzheimer’s Jamaica’s Memory Club, and UWI STRiDE Jamaica’s Dementia Care Management Consultations). These NGOs and individual volunteers are, for the most part, funded entirely from charitable donations or self-funded. In a few cases, tax-exempt social welfare organisations, such as the Lions Club, have sponsored the initiation of incorporated voluntary organisations, such as The Heart Foundation of Jamaica, which then developed its own model for financing, such as providing services for which users are charged a small fee.

3.3. Long-Term Care System Governance and Financing

To date, there have been limited, if any, attempts from the state to manage the LTC market. This reality is evident in the wider LAC region that lacks any comprehensive LTC market or strategy, arguably hindered by micro and macro-economic challenges [4]. Of note, Uruguay is the only country within the region that includes LTC in its National Integrated Care System. Despite this, their system prioritises infant care, and its sustainability is uncertain due to current and future financing challenges [4]. Neither the desk review nor consultations conducted to date suggested attempts in Jamaica to encourage service development either through tax breaks or other forms of financing. Similarly, there is no government strategy for LTC. The different services that are provided by the healthcare system, social services, and disability programmes linked to the social security system are, as in many other countries [22], under the jurisdiction and management of different ministries, agencies, and government levels. There seems little strategic coordination between the national and local levels and/or among different ministries.

3.3.1. Ministries Responsible for Long-Term Care

The management, regulation, and financing of LTC in Jamaica emphasizes public LTC institutions. There are few provisions that acknowledge and address the reality that Jamaica’s LTC system depends substantially on informal care.

Two ministries are key for public LTC institutions. The Ministry of Local Government and Community Development (MOLGCD) is responsible for the management of the day-to-day activities of the infirmaries. The MOHW is responsible for the registration and monitoring of private long-term care homes such as residential and nursing homes in Jamaica. The MOHW’s Standards and Regulation Division focuses on quality improvement and monitoring of both the public and private health sector. These two ministries often function independently of each other with little coordination of services and activities, especially as they receive distinct budgetary allocations to manage their portfolios.

The Bellevue Hospital also falls under the MOHW’s jurisdiction. This presents a unique situation with respect to the care of the sometimes decades-long chronic patients at the facility: instead of being managed and financed by the MPLGCD they are being financed by the MOHW. This situation sheds further light on the need for cross-ministerial coordination as often persons needing LTC move between different institutions depending on changes to the level of care and supervision required. When these movements occur, however, in the absence of an overarching framework, policy, or strategy that facilitates cross-ministerial management of cases, there are often financial, administrative, or other challenges in case management and care coordination.

3.3.2. Financing Long-Term Care

The Ministry of Finance (MOF) funds the Bellevue Hospital and infirmaries through revenue earned primarily from taxation (89.4%) [31]. Other sources include non-tax revenue (9.25%), capital revenue (0.48%), grants (0.87%), and loan receipts. The funds are disbursed from MOF to the MOHW, which directly finances Bellevue Hospital. The total mental health expenditure (estimated as a percentage of government health expenditure) is 6%. Approximately 80% of this mental health budget is allocated to Bellevue Hospital, which means that there is little of the already small mental health budget available for community mental health services and public sector LTC services. For the infirmaries, the MOF disburses funds to the MOLGCD, which then allocates through each local parish authority to fund their infirmaries.

Social Security

The National Insurance Scheme (NIS) is a social security scheme providing coverage to all formally employed persons (compulsory contributions) and voluntary contributors. For pensioners, NIS offers health coverage, the NI Gold Health, which covers doctor visits, prescription drugs, diagnostic services, dental/optical services, surgeon fees and hospital room and board. It does not, however, cover residential care costs such as nursing homes, institutional care, or paid home-based care such as nursing. NIS pension recipients are disproportionately from the richest quintile in Jamaica with over 80% of the poorest quintile not receiving NIS pensions or its associated health insurance benefit [21]. These data suggest that components of public support as they are disbursed and received exacerbate rather than narrow socioeconomic inequalities.

Other Relevant Social Protection Schemes

The Programme of Advancement through Health and Education (PATH) is a conditional cash transfer programme for those destitute or unable to care for themselves. Approximately 75% of PATH recipients are from female-headed households, with an estimated 16% of the recipients being elderly and persons with disabilities [21]. In February 2021, under the PATH programme, the Government of Jamaica launched a Social Pension Programme for persons 75 years and older who do not benefit from any other social assistance programme [34]. The new programme aims to provide beneficiaries with J$3400.00 per month, representing only 12% of the monthly minimum wage. Ironically, many who are not actively contributing to the NIS are also not poor enough to meet eligibility criteria for the PATH programme [21].

Remittances

Remittances in Jamaica are an essential source of financing for many Jamaican households—with 49.3% of households receiving remittances in 2017 [9], with higher socioeconomic status (SES) households receiving the greatest proportion of remittances between 2008 and 2017 [9]. Many Jamaicans rely on the remittances to supplement household income for necessities such as food, utilities, and education. A national survey of remittance recipients conducted in 2010 found that the majority of remittance recipients are female (75%), single (60%), between the age of 26 and 40 (44.4%), received at least a secondary school education (61.9%), lived in a household size of four persons (21.4%), and received remittances monthly or more frequently (59%) [35].

While remittances play an important role in Jamaica’s economy, contributing most recently to US$2.18 billion to the economy in 2019, its direct impact on the financing of LTC is unknown. There are no data that offer household remittance usage data granular enough to identify how much is spent on LTC. Consultations and KEIE events suggest that remittances play an integral role in Jamaica and in fact, support family caregivers of those living with dementia. Remittances function as an additional and sometimes only source of income for the out-of-pocket financing needed to fulfil their family member’s LTC needs.

4. Discussion

This overview of the LTC system in Jamaica highlights four key findings. The first is that Jamaica’s LTC system depends substantially on informal care. This is constituted of unpaid at-home care that mostly female relatives provide, as well as paid care provided by domestic workers and others who do not receive legal employment contracts. The reliance on informal paid care from women from rural communities leaves those communities with care burdens that fall disproportionately on the women and children that remain there. This type of arrangement is not sustainable given changes in female labour force participation and reductions in family sizes. It also exacerbates inequalities in access to care—higher socioeconomic groups have resources and assets that facilitate buying in of domestic and personal care and those from lower socioeconomic strata are without these services.

The second finding is that there is minimal strategic coordination for LTC between different parts of the state sector, or across state, private, and volunteer sectors. The concentration of state support for LTC on public institutions that involve multiple ministries translates into practical challenges for the coordination of care for persons needing LTC. Further, the disproportionate focus on public institutions across multiple ministries neglects the role that informal care plays in LTC. It inadvertently contributes to a growing informal care gap as the out-of-pocket payments and private financing needed for LTC is less accessible to those with fewer financial resources [22,23,24]. A more strategic state involvement, for example with state supported expansion of formal in-home services, will provide individuals, particularly women, with the opportunity to participate in the formal labour market and to be compensated for their care work [4]. For example, in South Korea, the expansion and strengthening of their LTC system led to the employment of 1 million people since 2008, with 95% of the LTC workers being women [4,36].

The third finding is that compulsory insurance and social protection schemes appear to exacerbate rather than narrow socioeconomic inequalities in LTC. Those most able to pay for care whether at-home or in a private facility are those with private assets and those who are able to navigate the often complex paperwork and other administrative requirements to take advantage of the public sector schemes. Access to public sector resources is not easily accessible to those who are employed in the informal sector without employment contracts and health insurance packages. Indeed, the current disproportionate reliance on informal care translates into those who are poorest assisting the wealthier with their LTC needs [22,23].

The fourth finding speaks to the lack of systematic LTC data gathering and related information systems—for both institutional and community-based care. Data gaps are evident in censuses of informal carers, in censuses of persons receiving LTC in private facilities, and in the lack of evidence of the true cost of LTC. For example, in cases of dementia, socioeconomic costs begin to incur often long before the first sign of dementia [23]. However, social and health services and social and health systems in LMICs such as Jamaica are neither sensitized to this nor set up for the type of longitudinal collection of administrative data from records (e.g., patient medical records) that can help to inform discussions of true-socioeconomic costs. While there is a major initiative toward the implementation of electronic health records at hospitals and clinics island-wide by 2022, the reliance on the paper-based patient records to date presents challenges in gleaning changes over time within and across individuals who use the healthcare services and there is no linkage between the healthcare systems data and the social care services databases. Further, while ADI has produced estimates of the costs of dementia care for the LAC region, with models of current and projected costs for specific countries, country-specific data are required. Greater strategic coordination between the entities that collect information is an important first step in this area. For example, including one question in national surveys, similar to that asked as part of the UK census (“Do you look after, or give any help or support to, anyone because they have long-term physical or mental health conditions or illness, or problems related to old-age?”) can help with gauging the true care needs.

5. Conclusions

For Jamaica’s LTC system to address its ageing population, there must be aspirational and concrete actions for a national, coordinated investment into community-based care. Family caregivers must be able to receive compensation, to get reprieve through in-home respite care, and/or to benefit from live-in trained home care workers. This type of legislated and state financed care infrastructure for at-home and community-based LTC, ageing- and dementia-inclusive infrastructure, and LTC facility development can help future-proof LTC for Jamaica’s ageing population. Further, harmonized and coordinated data-gathering from public and private care providers will reinforce this proposed LTC system.

The current case study provides a framework for other LMICs to critically assess their LTC system, identify service and system gaps, underscore the need for sustainable LTC investments and provide tailored recommendations within specific country contexts. Similar national case studies will expand an evidence base on the gravity of the issue and create opportunities for regional and global collaborations, including the pooling of resources.

Author Contributions

Co-conceptualisation, expertise in local context, summarising of relevant information, drafting and revising, I.G., J.N.R., R.A.; Co-conceptualisation, expertise in LTC, drafting and revising, A.C.-H., K.L.-D.; Data summarising, reviewing and editing, M.S.; Senior author, reviewing and editing, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the UK Research and Innovation’s Global Challenges Research Fund via the Economic and Social Research Council (ES/P010938/1). For more information on the STRiDE project please visit: https://www.stride-dementia.org/.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not yet publicly available as data collections are ongoing as part of the wider multinational STRiDE Research Project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Eldemire-Shearer, D.; Mitchell-Fearon, K.; Laws, H.; Waldron, N.; James, K.; Holder-Nevins, D. Ageing of Jamaica’s Population—What Are the Implications for Healthcare? West Indian Med. J. 2014, 63, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldemire-Shearer, D.; James, K.; Waldron, N.; Mitchell-Fearon, K. Older Persons in Jamaica. 2012. Available online: https://www.mona.uwi.edu/commhealth/sites/default/files/commhealth/uploads/EXECUTIVE%20SUMMARY.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Eldemire-Shearer, D.; Eldemire-Shearer, D. Ageing: The response yesterday, today and tomorrow. West Indian Med. J. 2008, 57, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bloeck, M.C.; Galiani, S.; Ibarraran, P. Long-Term Care in Latin America and the Caribbean? Theory and Policy Considerations; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafagna, G.; Aranco, N.; Ibarrarán, P.; Oliveri, M.L.; Medellín, N.; Stampini, M. Age with Care: Long-Term Care in Latin America and the Caribbean; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kämpfen, F.; Wijemunige, N.; Evangelista, B. Aging, non-communicable diseases, and old-age disability in low- and middle-income countries: A challenge for global health. Int. J. Public Health 2018, 63, 1011–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prynn, J.E.; Kuper, H. Perspectives on Disability and Non-Communicable Diseases in Low- and Middle-Income Countries, with a Focus on Stroke and Dementia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Sun, M.; Li, X.; Lu, J.; Chen, G. Effects of Disability Type on the Association between Age and Non-Communicable Disease Risk Factors among Elderly Persons with Disabilities in Shanghai, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planning Institute of Jamaica; Statistical Institute of Jamaica. Jamaica Survey of Living Conditions 2017. Available online: https://www.pioj.gov.jm/product-category/annual-publications/jamaica-survey-of-living-conditions/ (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- UNFPA and HelpAge International. The Desk Review of Situation of Older Persons; UNFPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Farina, N.; Ibnidris, A.; Alladi, S.; Comas-Herrera, A.; Albanese, E.; Docrat, S.; Ferri, C.P.; Freeman, E.; Govia, I.; Jacobs, R.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of dementia prevalence in seven developing countries: A STRiDE project. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 1878–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. PAHO Regional Plan of Action on Dementia in Older Persons Action Taken during the Campaign. Available online: https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2015/CD54-8-e.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- World Health Organisation. World Report on Disability 2011; WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data: Malta, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. World Report on Ageing and Health; WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Scott, S. Report on the Situational Analysis of Persons with Disabilities in Jamaica; UNICEF & Digicel Foundation: Kingston, Jamaica, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hasmuk, K.; Sallehuddin, H.; Tan, M.P.; Cheah, W.K.; Ibrahim, R.; Chai, S.T. The Long-Term Care COVID-19 Situation in Malaysia. 2020. Available online: https://ltccovid.org/2020/10/09/updated-country-report-the-long-term-care-covid-19-situation-in-malaysia/ (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- CaPRI. Low Labour Productivity and Unpaid Care Work; CaPRI: Kingston, Jamaica, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrant, G.; Pesando, M.; Nowacka, K. Unpaid Care Work: The Missing Link in the Analysis of Gender Gaps in Labour Outcomes; OECD: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe-Brown, I.; Taylor, R.J.; Chatters, L.M.; Govia, I.; Matusko, N.; Jackson, J.S. Kinship Support in Jamaican Families in the USA and Jamaica. J. Afr. Am. Stud. 2017, 21, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, K.; Thompson, C.; Holder-Nevins, D.; Willie-Tyndale, D.; McKoy-Davis, J.; Eldemire-Shearer, D. Caregivers of Older Persons in Jamaica: Characteristics, Burden, and Associated Factors. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CaPRI. Come Mek Wi Hol’ Yuh Han’: The Components of an Effective Social Safety Net for Jamaica; CaPRI: Kingston, Jamaica, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Herrera, A. Peer Review on Financing Approaches to Long-Term Care Thematic Discussion Paper; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; pp. 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- El-Hayek, Y.H.; Wiley, R.E.; Khoury, C.P.; Daya, R.P.; Ballard, C.; Evans, A.R.; Karran, M.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Norton, M.; Atri, A. Tip of the Iceberg: Assessing the Global Socioeconomic Costs of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias and Strategic Implications for Stakeholders. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 70, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brimblecombe, N.; Fernandez, J.-L.; Knapp, M.; Rehill, A.; Wittenberg, R. Review of the International Evidence on Sup-port for Unpaid Carers. J. Long-Term Care 2018, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaica Observer Limited. Public Access to Infirmaries Islandwide Restricted; Jamaica Observer: Kingston, Jamaica, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Wellness. Ministry of Health: Taking Responsibility 2018 Sectoral Presentation. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.jm/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/MOH-Sectoral-2018-Online.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Ministry of Health Jamaica. Ministry of Health Guidelines For Standards and Regulation Division Community and Private Health Facilities Supplementary to Guidelines for Community and Private Health Facilities. Available online: https://moh.gov.jm/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Guidelines-for-Community-and-Private-Health-Facilities.doc (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Ministry of Health and Wellness. Facilities Currently Registered under the Nursing Homes Registration Act 1934 Parish Facility Type of Facility Certification Period Date Approved Expiration Date. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.jm/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/2019-gazette-list_final.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Daley, J. Nursing Homes in Breach—Majority of Elderly Care, Indigent Facilities Fail COVID-19 Inspection; Jamaica Gleaner: Kingston, Jamaica, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Statistical Institute of Jamaica. Population Statistics 2017. Available online: https://statinja.gov.jm/Demo_SocialStats/PopulationStats.aspx (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Ministry of Health and Wellness. Auditor General’s Department Performance Audit Report Ministry of Health (MOH) Management of Mental Health Services Rehabilitation And Reintegration of the Mentally Ill. 2016. Available online: www.auditorgeneral.gov.jm (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- The Caribbean Palliative Care Association. Available online: https://www.caripalca.org/jamaica (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Ministry of Labour and Social Security. National Policy for Senior Citizens (Green Paper) 2018. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.jm/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/NHIP-Greenpaper-2019-Edited-7_5_19-Final.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- JIS. Cabinet Gives Approval For New Social Pension Programme—Jamaica Information Service. Available online: https://jis.gov.jm/cabinet-gives-approval-for-new-social-pension-programme/ (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Ramocan, E.G. Remittances to Jamaica: Findings from a National Survey of Remittance Recipients; Bank of Jamaica: Kingston, Jamaica, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. Overview of Korean Long-Term Care Insurance. Available online: https://idbdocs.iadb.org/wsdocs/getdocument.aspx?docnum=EZSHARE-1178471419-10 (accessed on 2 May 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).