Abstract

This study examines the problem of the fragmentation of asynchronous online discourse by using the Knowledge Connection Analyzer (KCA) framework and tools and explores how students could use the KCA data in classroom reflections to deepen their knowledge building (KB) inquiry. We applied the KCA to nine Knowledge Forum® (KF) databases to examine the framework, identify issues with online discourse that may inform further development, and provide data on how the tools work. Our comparisons of the KCA data showed that the databases with more sophisticated teacher–researcher co-design had higher KCA indices than those with regular KF use, validating the framework. Analysis of KF discourse using the KCA helped identify several issues including limited collaboration among peers, underdeveloped practices of synthesizing and rising above of collective ideas, less analysis of conceptual development of discussion threads, and limited collaborative reflection on individual contribution and promising inquiry direction. These issues that open opportunities for further development cannot be identified by other present analytics tools. The exploratory use of the KCA in real classroom revealed that the KCA can support students’ productive reflective assessment and KB. This study discusses the implications for examining and scaffolding online discussions using the KCA assessment framework, with a focus on collective perspectives regarding community knowledge, synthesis, idea improvement, and contribution to community understanding.

1. Introduction

Asynchronous online discussions are popular in educational settings that emphasize inquiry and collaborative knowledge construction. The goals of using discussion forums include the elicitation of a wide range of views, critical thinking, problem solving, and inquiry [1,2,3], and are theoretically undergirded by social constructivist perspectives on learning. However, despite high participation rates, online discussions often end prematurely [4], and different discussions in a course are unconnected. This leads to a fragmented and incoherent whole, in which many discussions are incomplete and there is little synthesis of advances across the discussion space. Coherence is especially important in approaches in which online discussion is intended to be a major and continuous mode of knowledge construction, such as the knowledge-building model of Scardamalia and Bereiter [5,6]. In knowledge building (KB), students use the Knowledge Forum® (KF) online environment to collaboratively improve their class’s ideas over weeks or months. To address these issues in online discussions and for developing sustained KB, students need evidence of how their online discussions as a whole are developing, to monitor and reflect on collective advances, and to regularly formulate deeper levels of conceptualization for collective problem solving and ideation.

Learning analytics has grown rapidly over the last decade. The field of learning analytics is interested in the use of the data that are stored in digital learning environments such as discussion forums to discover patterns in interaction that contribute to learning [7,8,9]. It aims to “harness unprecedented amounts of data collected by the extensive use of technology in education” [10] to provide useful insights to enhance teaching, learning, and educational management [11]. Considerable progress has been made in learning analytics as a support for learning [12]. However, learning analytics generally focuses on researcher and teacher use for formative assessment and feedback, rather than student agency and higher-level pedagogical purposes [13,14]. Further, relatively few learning analytics are designed to provide data/evidence to facilitate students’ reflection on and assessment of collective learning, and to cultivate students’ higher-order thinking skills (e.g., regulation and metacognition) for knowledge creation [13,14]. Moreover, relatively few studies ground the design and practices of learning analytics in educational theories and pedagogical practices, although many researchers have call for attention to this [10,15,16]. Therefore, a framework and tools that are grounded in learning sciences theories and pedagogical practices are needed to help students focus on collective features of online collaborative inquiry, scaffold their ongoing monitoring and reflection on collective advances in their online discourse, and build their “big picture” understanding of a domain.

The study was to use the Knowledge Connections Analyzer (KCA) framework and tools to examine the problem of the fragmentation of online discussions, in the context of sustained inquiry and collective knowledge work in computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL), and explore how students could use the KCA data in classroom reflections to deepen their KB inquiry. The Knowledge Connections Analyzer (KCA) framework and tools are grounded in the influential pedagogical model of KB and help students investigate, reflect on, and direct their online collective KB discourse from four angles: (a) collective and democratic knowledge; (b) links between multiple contributions, syntheses, and rise-above insights; (c) idea improvement; and (d) promisingness judgments and individual contributions to the community. While the KB approach and KF have been used widely, there are issues with online discourse that may not be detected by embedded KF tools or other analytical tools but are nevertheless critical for supporting productive online discussion in terms of contributing notes, attending to peers’ notes, developing discourse coherence, and building knowledge. Here, CSCL is defined as “a field centrally concerned with meaning and practices of meaning-making in the context of joint activity and the ways in which these practices are mediated through designed artifacts” [17]; it deals with three constituents—collaborative learning as meaning making, approaches to mediation through designed artifacts, and methodologies for studying of the two facets of CSCL [18].

2. Literature Review

2.1. Problems with Asynchronous Online Discussions

The literature has identified a range of problems with participation, interactivity, inquiry, and knowledge construction during asynchronous online discussions [1,4,19,20]. Hewitt’s [4] investigation of why discussion threads “die prematurely” suggests students rarely return to a note after reading it, nor to a mostly read discussion thread. Peters and Hewitt [21] found students often attend to others’ notes very briefly. Wise et al. [20] further showed students attend to peers’ posts in diverse patterns, such as minimal attention to others’ posts, viewing many notes superficially, and paying extended attention to selected notes ignoring others. Primarily, paying minimal attention to the notes of others leads to shallow and disjointed discussions [22], which Wise et al. [19] characterized as “a series of parallel monologues rather than a true discussion.”

Even with acceptable note-writing productivity, notes are frequently fact-oriented and lack the conjectures necessary for sustained inquiry [23]. Interactions may also be socially rather than cognitively oriented. Although such an orientation maintains the social relations enabling collaboration [24], it can overshadow more cognitive contributions. Thus, discussions frequently remain at the knowledge-sharing level, accumulating ideas without reaching agreement or solving problems, with little collaborative knowledge construction or synthesis. These problems become prominent when note-writing productivity is high, with many good ideas being lost in a large volume of notes [25]; students sometimes find lack of response to their ideas discouraging. Teachers often assess online discussions on the basis of the quantity and quality of individual students’ notes, and not on the merit of what is achieved together (i.e., at a group or class level). The resulting lack of apparent conceptual progress and synthesis can suggest that the online work is not educationally valuable.

As such, we propose that, besides online discourse in which students attempt to solve problems at hand for domain knowledge, they need to examine evidence of how the overall discourse is developing for their reflection and future action. The discourse by which students consider this evidence is called metadiscourse, because it is not solely about domain problems, but also the nature of the discourse itself [5]. The KCA framework and the tools premised on KB model are designed to provide students and teachers this evidence for reflection and improvement.

2.2. Knowledge Building (KB) and Knowledge Forum (KF)

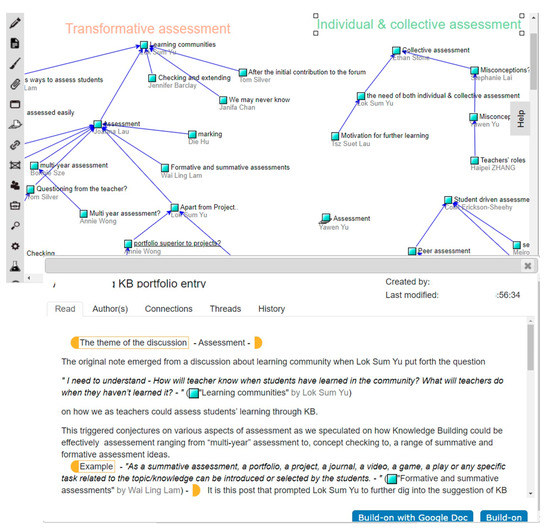

KB is an educational model that attempts to refashion education to “initiate students into a knowledge creation culture” [5]. The main ideas of KB are expressed by 12 principles [26] that emphasize that KB is an open-ended journey of idea improvement, is the accomplishment of a community, and that student agency and metacognition are central. At the heart of KB is online discourse, most typically in KF (Figure 1). Whereas most discussion forums provide affordances for writing, revising, and responding to notes, KF is designed to help students focus on theory building in their note writing/reading, and provides tools for working with ideas. Many descriptions of KB, with details of its underlying principles and recent research findings, are available in the learning sciences literature [3,5,6,27].

Figure 1.

Knowledge Forum (KF) view and reference notes.

In the last 30 years, KB has been implemented in K-12 classrooms in many countries, and in a broad range of subjects including science, mathematics, and social studies; in medical education; and in teacher education. While KB research using KF has shown substantial progress in classroom design and discourse analysis [3,12,23,28,29], the problems of fragmented notes, in some ways similar to those in online discussion, continue to persist. With the emphasis placed on developing sustained inquiry and higher-level conceptualization, helping students to work on coherence and sustained inquiry and improving their discourse continue to be a key issue in KB research. There have been different efforts in using visualization tools [30,31] or varied classroom designs (e.g., portfolios [32]), but the development of a reflective assessment framework based on key KB ideas and accompanying analytical tools to be used by students are still lacking. This paper proposes using the KCA framework and analytical tools to support students to reflect on their own KB to address these problems.

2.3. Learning Analytics in KF

Learning analytics is commonly defined as “the measurement, collection, analysis and reporting of data about learners and their contexts, for purposes of understanding and optimising learning and the environments in which it occurs’’ [33]. The primary purpose of learning analytics is to support students’ agency and development of higher-order skills and therefore enhance students’ learning [13,14]. Aligning with this purpose, a suite of analytical tools that are grounded in KB pedagogical theory and practices have been developed in the KB field. These analytics tools that are integrated in KF include the previously developed Analytic Toolkit (ATK) using log data [34] and the applets on vocabulary and social network analysis (SNA) developed later. These tools generate sociograms that visualize reading and build-on activities and calculate the corresponding network densities [31]. Zhang et al. [35] used network density for reading to measure awareness of contribution of peers and used network density for build-on or reference networks to measure connectedness to peers.

Recently, some new analytical tools have been embedded in KF, namely, the Promising Ideas Tool (PIT) [36], the Idea Thread Mapper (ITM) [27], and the Knowledge-Building Discourse Explorer (KBDex) [30]. The PIT helps students select promising ideas from their online discourses and supports them in collectively deciding on the most promising directions for subsequent work. The tool does this by aggregating and displaying their selections [36]. The KBDex analyzes the dynamics of collective knowledge development and individual contributions by focusing on conceptual ideas and keyword densities [30]. The ITM, which is a time-based collective discourse mapping tool, captures collective structures and unfolding strands of knowledge practices in long-term online discourse. This analysis tool helps students make purposeful contributions and connect their efforts [27].

The development of these tools indicates a growing trend toward examining the collective aspects of assessment. However, the KBDex is primarily a research tool and is not designed for student use. The PIT and the ITM are more commonly used for decision-making than for reflection and are often applied for the specific KB tasks that help students choose promising ideas and develop deeper discourse. By considering the fundamental role of reflection in learning (i.e., How People Learn [37]), we propose a need for tools that support students’ reflective assessment and enable them to achieve community goals. Students need tools that can serve as scaffolds to help them engage in collective monitoring and reflection on their online discourses. They need tools that can produce deeper levels of conceptualization, rather than fragmented discussions. The KCA was developed to address these needs. Reflective assessment is a type of assessment in which learners, as active agents, collectively reflect on data regarding learning processes and outcomes to regulate and improve their ongoing learning [3,26,29,38].

2.4. The Knowledge Connections Analyzer (KCA)

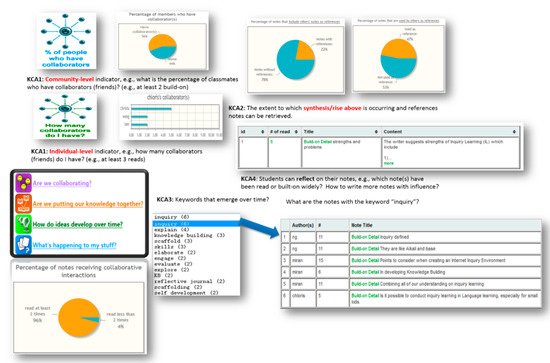

We developed the KCA informed by KB theory and practices, which emphasizes collective responsibility for knowledge advancement in a community [5,6]. The KCA framework comprises four inquiry questions and a set of designed tools to help students assess, reflect on, and further deepen their KB; the KCA tools comprise web-based software that retrieves data relevant to these questions from a KF database and presents them in formats designed for students’ collective reflection on and improvement of their online work. Table 1 and Figure 2 shows the KCA questions, their purposes, and the corresponding KB principles and perspectives, and the output for each KCA question, respectively. For a full description of the four questions and output for the four inquiry questions [39]. The framework and tools were designed to bring collective features of KB into focus, engage students and teachers in metadiscourse, and further scaffold students’ collective monitoring of and reflection on their discourse. “Metadiscourse” here refers to discourse about the nature of the discourse by means of which students develop domain knowledge [5].

Table 1.

Key inquiry questions, purposes, principles, and information of the Knowledge Connections Analyzer (KCA) framework and tools.

Figure 2.

Knowledge Connections Analyzer (KCA): interface, questions, and output.

2.5. Research Goals and Questions

This study was part of a larger project investigating the design, process, and effects of reflective assessment with the KCA. The focus of this study was to examine the KCA framework and tools. The research goals included (a) examining and validating the KCA framework and tools by analyzing various databases, (b) identifying issues that arise in online KB discourse as a step toward exploring further possibilities for conceptual development, and (c) examining students’ uses of the KCA to support their processes of reflective assessment. The research questions were as follows:

- How does the KCA assess the various facets of KB that inform collaboration, synthesis, conceptual progress, and individual influence on community in online KF discourse, and how do the KCA indices differ when comparing databases of more or less sophisticated design?

- How does the KCA reveal the progress and development issues in online KB discourse through its comparisons of various databases?

- How do students interpret the KCA output in their classrooms and use the KCA-generated data to support their reflections?

3. Methods

3.1. Research Contexts

The data for our KCA analysis were drawn from 9 KF databases, which were selected from a teacher professional development project that involved 50 teachers in Hong Kong. This project examined how KB pedagogical models could be implemented and scaled up in Asian classrooms, and involved seconding experienced KB teachers who collaborated with both researchers and novice KB teachers. The project activities included curriculum design meetings between the seconded teachers and researchers, subject area and school-based meetings for new teachers, and network-wide university-based workshops.

The participating teachers used a four-phase pedagogy model, which emerged through a teacher–researcher design that embedded KB principles in classroom practice. The phases in this model were (1) creating a collaborative classroom culture for KB, (2) engaging students in problem-centered collective KB, (3) deepening inquiry on KF, and (4) advancing KB discourse through embedded and transformative assessment involving reflective and portfolio tasks. All nine KF databases were selected from classrooms with KB teachers who used this general pedagogical method. However, the teachers had various ways of implementing KB designs, and only some of them used portfolio assessment tasks (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Detailed information about the databases.

3.2. Data Sources

3.2.1. Data from KF Databases and Their Selection

The nine databases were selected to show maximum variety in terms of achievement, academic level, academic subject, in their methods of principle-based portfolio assessment and co-design in KB, and in their quantity and quality of online contributions. This variation was necessary for the sake of comparison and validation. From each database, one or more views were selected, which represented a unit of study. The views we considered most promising for analysis were selected on the basis of log data statistics on usage, visual inspection of interaction patterns in the views, and SNA.

From the nine KF databases, a total of 353 students and 4476 computer notes were included. Table 2 summarizes the nine databases, in terms of the school’s academic achievement level, curriculum and class size, number of days on KF, total number of notes created, and whether reflective portfolio assessment was used. In Hong Kong, secondary schools are divided into three bands on the basis of their performance in examinations in Grade 6: Band 1 (best performing) through to Band 3 (worst). The sample thus included databases ranging from schools of all bandings. The teachers all had at least several years of experience with KB, but all students were new to it. As Table 2 shows, the duration of their work on KF varied considerably; DB5, for example, shows only 18 KF days, yet students were nevertheless quite active, writing 370 notes.

These databases were selected to show variation, comparison, and validation of the KCA results. Some databases were selected because they had been studied before in other published studies and could provide points of reference for interpreting the KCA results. Many teachers were assigned self-assessment KF tasks, but these tasks ranged in complexity from simple reflection notes in KF (DB4 and DB5) to sophisticated principle-based portfolio designs that analyzed discourses using KB principles (DB8 and DB9). Some databases assessed in other studies involved greater collaboration in pedagogical design between teachers and researchers (DB1, DB7). In general, four databases (DB1, DB7, DB8, and DB9) involved a stronger design focus and were expected to show different KCA results from the others. The KCA was applied to the nine databases, and we examined the results concerning each of the four key questions—which concerned collaboration, synthesis, idea improvement, and individual influence on the community. Comparisons across these databases were made to validate the KCA data and help identify or reveal the patterns and problems of online discussion.

3.2.2. Data on Student Reflection on the KCA Output and Analysis

The data on student reflections were drawn from a Grade 11 class that consisted of 20 low-achieving students. These students performed at or below the 10th percentile in their public examination results in Hong Kong. They were weak in communication, collaboration, critical thinking, motivation, and metacognition. They were taking a course on Visual Arts and made inquiries on the topic of “art and art evaluation” whenever appropriate during the course, which lasted five months with one lesson each week. Art and art evaluation was one of the core topics of the visual arts curriculum. The students’ work involved small-group collaborations, whole-class discussions, individual and collaborative note writing (offline and online), and individual and collaborative reflection. The students were facilitated by an experienced teacher who had used KB for eight years to teach visual art.

The teacher used a three-phase KB pedagogical model to help the students engage in productive KB. These three phases were (1) helping students build the capabilities of inquiry, collaboration, and metacognition necessary for productive KB; (2) involving students in deepening their problem-centered inquiries in KF; and (3) encouraging students to make KB inquiries and develop a deep domain-relevant understanding through reflective assessment with the KCA [38]. To use the KCA, the students were provided with prompt sheets that gave both content-related and metacognitive prompts for the following KCA inquiry questions: “What have I done with the KCA and what are the results?”; “Why did I do this analysis?”; “What problems have I discovered, and what have I found out from the analyses?”; “What are my questions, and what do I not quite understand?”; and “What can I do to improve my current work on KF?” The KCA prompt sheets were distributed to the students in each lesson and were collected a week later. Some students completed their reflection journals and prompt sheets in class, whereas others completed them later.

The data for our study were drawn from the researcher-designed student prompt sheets, which combined the reflective journals and the KCA prompt sheets. The KCA prompt sheets were used to record the students’ multiple sets of KCA results, their interpretations and reflections on the data, and their action planning. When analyzing the prompt sheets, we first identified the productive and unproductive uses of the KCA data. Next, we selected a limited number of events related to KB goals, such as synthesis/rise-above and idea improvement. We also analyzed the potential of the students’ reflections on the KCA data for enhancing their progress toward key KB goals.

4. Results

4.1. Examining the State and Issues of the Online Discourse as Revealed by the KCA

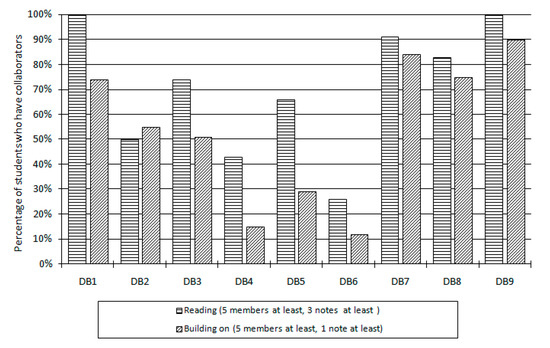

KCA-1: Are we a community that collaborates? To investigate the state of collaboration practice in the databases selected, we used the data provided by the KCA to create a quantitative overview. The results were presented in pie charts by the KCA but are aggregated in bar graphs here to facilitate comparison between databases (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage of students who have an audience for their work.

Comparison across databases show that those with more sophisticated designs, that is, principle-based portfolio designs (DB8, DB9) and strong researcher-teacher co-design (DB1, DB7) had higher KCA indices (80–100%). On the other hand, the databases with less specific designs (DB4, DB5, and DB6) did not meet the criterion. For example, for DB4, the percentage was slightly more than 40%, and therefore more than half of the students in the class did not have at least five students who had read at least three of their notes. We consider the requirement we tested to be modest, since most classes had around 40 students. KB may require familiarity with the work of more students, and more interaction is needed. The comparison of the KCA data across the different databases validated what we had found in our earlier studies [41].

In relation to development issues in the present setting, one may wonder how much reading effort would be needed to reach 100%. As Table 2 shows, students were generally reading enough, but more effort needed to target the writing of more students. While reading the writing of more students would improve familiarity with the ideas in the database, focused reading, which typically involves a relatively small group of students, is necessary for knowledge-constructing dialogs; Zhang et al. [35] found an average clique size of 5.74 students when students were free to form collaboration groups, but students participated in many such groups. Thus, a combination of reading the work of many students and engaging in dialogs in smaller groups was necessary; however, this did not require a very large amount of reading.

The data for build-on notes in Figure 3 paints a similar picture to the reading data. Findings from DB7, DB8, and DB9 show that principle-based portfolio design and co-redesign between teachers and researchers could facilitate students engaging in productive collaboration, and comparison of these different databases illustrates similar patterns validating the use of the KCA. Databases with more sophisticated pedagogy or assessment designs showed higher connectivity in both reading and build-on patterns and KCA indices compared to those with less intensive designs, in which students used KF in more general ways.

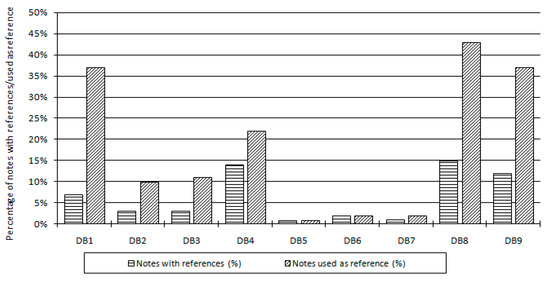

KCA-2: Are we putting our knowledge together? Figure 4 reports the percentage of notes that contained reference links, or that were used as references in other notes. Here too, there were variations among different databases—the databases using more intensive designs showed higher KCA indices. In DB8 and DB9, students created a reasonable number of reference notes, with 10% to 15% of notes having reference links, and 35–40% of notes being used as references. Most reference notes were portfolio notes, as evidenced by phrases such as: “Summary—The set of notes begins…” and “as I go through all the comments…” that link the note to the referenced material. This was expected, because these databases were constructed in studies investigating principle-based portfolio notes [32,41]. However, the KCA, by including note content in addition to quantitative indices, helped us detect there were few other uses of references; there were few KF notes with reference notes in DB2 through DB7.

Figure 4.

Percentage of notes with references and percentage of notes used as references.

While the use of portfolios increased the use of reference notes in some databases (DB1, DB8, DB9), the KCA also helped identify areas that can be improved. For example, students in DB1 created seven group portfolio notes with reference links; however, the number of notes to which reference was made was rather high, suggesting the students were not very discriminating in selecting material to discuss in their portfolio.

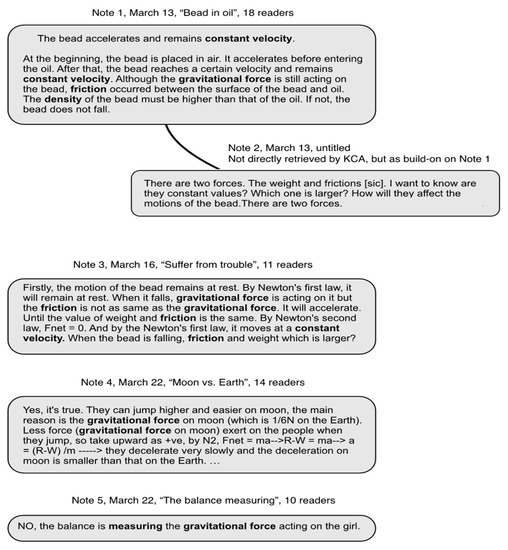

KCA-3: How does the community’s knowledge develop? For question KCA-3, the KCA first asks the user to enter the desired extent to which the notes must have been read to be included in the analysis; it then generates a list of keywords, ordered by the number of notes in which they were used that met the reading criterion. The user can then analyze the notes in which a specific keyword is used, in order to gauge whether they suggest evidence of domain learning by the community over time. To illustrate the main idea of the analysis intended for this inquiry question in the KCA, we report the results for several views on mechanics in DB7.

The views contained 266 notes, of which 85 were read by at least 10 students (roughly one-quarter of the class). These notes had 18 distinct keywords that were used in more than one note, with gravitational force being used most frequently. The transcript in Figure 5, generated from the KCA output, shows four notes containing the keyword “gravitational force” and one additional note that built onto one of these notes. All keywords in the transcript are shown in boldface.

Figure 5.

Note content for the keyword “gravitational force” generated by the query “How do our ideas develop over time?”.

Note 1 provided the phenomenological explanation that gravitational force continued to act when the bead moved through the liquid (correct), but that an additional force occurred due to the friction from the liquid (only partly correct; there also is a buoyancy force). Note 3 made some conceptual progress and provided a causal explanation that applied Newton’s First and Second Laws to the problem. This was a significant improvement on the explanation in Note 1, as a causal mechanism is an important aspect of explanation in science. Note 4 dealt with how high heavy and light persons could jump on the moon; it applied Newton’s Second Law correctly to a different physical situation involving the force of gravity. Note 5 made an incorrect assertion about the force of gravity in the context of a bathroom scale reading; it is the normal force from the floor that determines the reading.

Integrating knowledge across different inquiries in a domain involves a high degree of synthesis but is necessary for achieving “big picture” coherence in a whole course of study. The foregoing does not constitute the analysis of integration of knowledge across different inquires, but rather the analysis of one concept. For a more complete picture, different efforts along these lines must be combined. For example, further analyses of the friction and density concepts could begin to elaborate the relations among all three concepts.

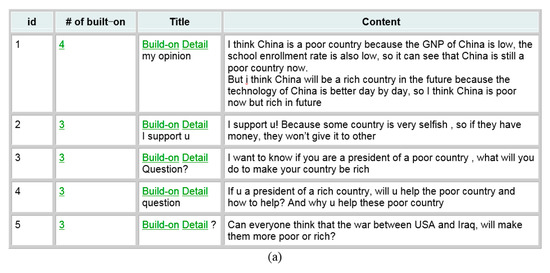

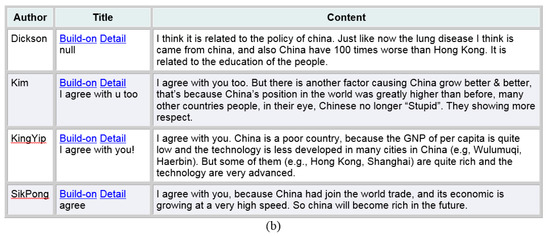

KCA-4: What is happening to my own contributions? For KCA-4, the KCA asks the user (the student who logs in) to enter the interaction type (e.g., build-on) and the extent of interaction and impact on community (e.g., at least three members involved); it then generates a ranked list of notes that have been built on by at least three members for the particular student (Figure 6). The student then can see how their notes have led to responses from others in the community, and whether these responses have been fruitful. This is similar to the notion of citation in scholarly community where one’s work is cited by others as knowledge develops. To illustrate the main idea of the analysis intended for this inquiry question in the KCA, we report (in in Figure 6b) the results for one note (titled my opinion) in DB8, generated by one student (Radford) to a moderate audience, that lead to four responses, retrieved in chronological order by the KCA.

Figure 6.

(a) The number of notes has been built on by at least 3 students, with specific times of build-on; (b) the four build-on notes to the note titled “my opinion”.

These five notes focused on the reasons why China is rich or poor. The note titled my opinion (Note 1) provided an explanation of why China is poor now and will be rich in the future. The note titled null (Note 2) stated that policy and education may be factors leading to poverty in China and was a necessary and important advancement on Note 1. The note titled I agree with u too (Note 3) further elaborated that China’s position contributed its richness, which enriched the factors due to which China was rich in Note 1. The note titled I agree with you! (Note 4) provided an elaborated explanation of why China is poor now (low gross national product (GNP) of per capita and less advanced technology) and why China has the potential to become rich (having some cities that are rich and having advanced in technology), which took up on the explanations offered in Note 1. The note titled agree (Note 5) provided an elaborated explanation on reasons why China would become powerful in the future (joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) and rapid economic growth). This showed uptake of ideas responding to the initial idea in Note 1. In sum, Note 1 led to a fruitful discussion in the community, and KCA data shows what is happening to the initial idea and how it has brought about others ideas—the five notes together explained well the factors contributing to China’s present poverty and future power.

4.2. Examining Student Uses of the KCA for Reflective Assessment in Classrooms

The following sections show some examples from the students’ writing on the prompt and/or reflection sheets, which illustrate how they interpreted the KCA output and how using the KCA guided their reflections.

4.2.1. Fostering Synthesis and Rise-Above as Collective Efforts through Reflective Assessment with the KCA

The following excerpt from a KCA prompt sheet demonstrates how a student was enabled to generate synthesis and rise-above ideas in a collective way through reflective assessment of the KCA data. This excerpt was written in response to the question “Are we putting our knowledge together?”

I did this analysis because I wanted to know whether we were good at advancing and deepening our inquiry and drawing conclusions by referring to others’ notes. I found that 96% of our notes did not contain references… 95% of our notes were not used as references… I found that we seldom referred to others’ knowledge to rise above our own notes, which makes me think that most students only focused on their own opinions rather than incorporating others’ knowledge in creating notes. I will improve my own notes. I will read more notes written by others, and integrate them into my notes in order to enrich my explanations. (from the KCA prompt sheet of student18)

In this excerpt, the student reflected on the KCA data with the aim of learning “whether we are good at advancing and deepening our inquiry and drawing conclusions by referring to others’ notes.” She identified related problems (“seldom refer to others’ knowledge to rise above our own notes” and “most students only focus on their own opinion rather than incorporate others’ knowledge”). These statements show that she had gained useful insight. This student sensed that improving ideas by integrating and referring to others’ notes was important. In her analysis, the student appeared to reflect on the quality of reference notes, made a plan (“improve notes”), and took action to bridge the gaps she perceived (“will read more notes written by others and integrate them in my notes”). In other words, the student generated important KB goals for improving her ideas through collaborative efforts (referring to others’ notes) and idea development. This example suggests that KCA-enhanced reflective assessment helped this student connect her learning orientation to the KB goal of idea improvement as a collective responsibility.

4.2.2. Fostering Idea Improvement through KCA-Aided Reflective Assessment

The following example from a KCA reflection journal suggests how KCA-assisted reflective assessment helped students focus on the KB principle of idea improvement.

I am wondering whether my notes are good. I find that my notes have been read and built on a lot; 90% of the notes have been followed by others. So, my notes may be not bad and have attracted a lot of attention… Of course, they have much room to be improved. I can use some examples and others’ notes to elaborate my ideas and enrich my explanations. (from the KCA reflection journal of student11)

This excerpt shows that this student analyzed the KCA data and assessed the quality of her notes (“my notes may be not bad and have attracted a lot of attention,” “they have much room to be improved”). These observations indicate useful insights, as the student sensed that progressively improving her ideas was important. On the basis of her analysis, she appeared to reflect on the quality of her notes, and more importantly, she identified problems and generated plans to address them (“use some examples and others’ notes to elaborate my ideas and enrich my explanations”). In other words, this student generated useful KB ideas, including the idea of making more references to others’ ideas.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study addresses the problems of asynchronous online discussion and proposes a new approach that is premised on knowledge-building (KB) theory and emphasizes collective inquiry. We pioneered the development of the KCA (which is a reflective assessment framework of inquiries pertaining to KB) and analytical tools to investigate participant responses. In this section, we discuss the key emerging themes and explain the theoretical, methodological, and design-related implications of our findings for KB and CSCL.

5.1. The KCA Framework for KB and CSCL

Although there are many ways to assess KB and online learning, this study contributes to the literature by examining the KCA reflective assessment framework and its related tools. The KCA framework proposes an approach that involves four key questions. These questions allow us to look at KB (and online discussion) from four angles: (a) collective and democratic knowledge; (b) links between multiple contributions, syntheses, and rise-above insights; (c) idea improvement; and (d) promisingness judgments and individual contributions to the community. This framework addresses important aspects of KB. It helps us rethink the nature and facilitation of online discussion and CSCL.

A key contribution of this study is that it applied the KCA framework not just to the context of KB, but also to the different contexts of asynchronous discussion (online discussion) and CSCL platforms. This application provides a conceptual map to assess and facilitate collective inquiry and improve the quality of discourse. The KCA framework and related tools are premised on KB, but their principles and questions can be used for purposes beyond analyzing KF databases. The KCA has wide applicability for examining and addressing the issues of online discussion and CSCL settings.

5.2. KCA Analysis as a Way to Identify Issues for CSCL and KB Development

The theory-driven KCA framework is supported by a range of KCA tools, which provide new methods of analysis and offer scaffolds for collective KB and for identifying areas where improvements are needed. In line with the current emphasis on learning analytics, KCA tools provide evidence relevant to the four key inquiry questions regarding student work in an online environment. This study included empirical analyses focused on comparing the KCA indices by using multiple databases drawn from KB classrooms.

We applied both sets of tools in the analysis of nine KF databases to validate them by using the empirical data they contain, as well as to investigate the current state of online KF discourse, thereby revealing areas for further development. Comparative analyses using the KCA indicated that the databases with more sophisticated pedagogy had higher KCA indices than the other databases. The KCA tools were found to be applicable to different databases, and variations in the designs of these classrooms helped validate the KCA framework and tools. The findings pointed to several kinds of potential issues. The KCA framework and tools were shown to provide new methods and to help enrich the possibilities for assessing KB for collective progress.

This study provides new perspectives and identifies the need for greater attention to both the nature of online discussion and pedagogical designs for community knowledge, synthesis and rise-above, idea improvement, and individual contributions to the community and to promisingness judgments. These four challenges are important not only for KB, but also for enriching CSCL and online discussion. Note that the issues we identified may not be salient for regular online analysis.

First, the use of the KCA tools proved important in assessing the nature of online discussion beyond examining levels of productivity and interaction. These tools enabled the participants to identify areas for improvement, such as using more rise-above responses and syntheses (KCA-2). Second, the students generally needed to read/build on the writing of more students (KCA-1). From a KB perspective, a distributed effort may be more effective. Third, the KCA analysis of the databases showed that students need more guidance on how to direct their efforts to collectively synthesize and rise above collective knowledge (as shown in the responses to KCA-2). The students tended to respond to individual notes, but did not build a coherent body of knowledge, as reported by other studies [19,42]. Furthermore, much more effort should be devoted to helping students focus on idea improvement, by analyzing conceptual progress in strings of notes (KCA-3) and by helping students identify promising ideas. Students need to inquire into the effects of their ideas on the wider community and to consider the output of multiple students together, thereby identifying patterns and combining insights (KCA-4).

This study also provides examples that illustrate how students use the KCA and how the accompanying reflection prompts them to engage in reflective assessment. Our study contributes to the literature by proposing various ways in which KB practices can be evaluated and improved through an assessment framework supported by analytics tools. CSCL tools such as the KCA, when used in conjunction with student reflection, can help support extra effort, thereby making the process more attractive and salient to students. Although the KCA is generally used in the KB context, it represents an important step forward in providing tools and methods for students to make their own inquiries into their discourses, thereby making complex analysis more accessible.

5.3. Implications of the KCA Framework for Pedagogy

In the KCA framework, theory, technology, and pedagogy are integrated. The KCA includes design and pedagogical implications that can support enriched CSCL and classroom practice. The KCA provides a general framework for productive discourse that emphasizes key aspects of KB. These aspects are based on explicit KB principles [26], but they are often neglected in classroom practice. The KCA targets some key areas that can be easily overlooked. These areas include the following:

- (1)

- Understanding that KB involves accomplishments at various levels of social organization, from individual students, to small groups, to the whole community, and that achievements at higher levels are not reducible to those at lower levels [43].

- (2)

- Going beyond writing, reading, and responding to individual notes in order to build a coherent knowledge base.

- (3)

- Analyzing the conceptual progress of the community.

The KCA can help teachers and students become more aware of these issues. Three additional suggestions for classroom use are discussed below.

First, in KB and CSCL classrooms, it is important to consider the difference between productivity and the actual generation of ideas. According to Pryor [44], frequent KF use may encourage a focus on improving the statistics. However, the focus should be on understanding the ideas behind the inquiry questions and acting in accordance with that understanding. Thus, the KCA may help teachers and students develop an understanding that KB is something a community does, and a matter of what the community is. Development in this direction is not driven by achieving higher percentages of comments, but by an understanding that the interchange should contribute to better KB. Teachers may use the KCA output and visualizations to help their students appreciate the different levels of contribution and the important role of community-level work.

A second consideration is alignment with conceptual progress. Basically, KB is often omitted from the school curriculum, and therefore students have limited opportunity to invest in developing and assessing the knowledge-building process. Therefore, it is important to integrate question KCA-3 into practice because this question focuses on the issue of progress in domain-related knowledge. One possible use of the KCA is to support investigations of community progress in idea development, for example by building an understanding of how core ideas in the Next Generation Science Standards [45] can develop when supported through the use of KF and the KCA. This emphasis on conceptual progress aligns well with the need to develop KB and other innovations that align with learning standards and domain-related knowledge.

A third consideration is better engagement of students in reflective assessment using the KCA or other CSCL tools to help them assess their discourses for KB. CSCL offers many KB and analytical tools, but a key theme is to help students reflect on the evidence produced by these analytical tools. Teachers also need to develop ways to engage students in productive, collaborative reflection, and dialogue. When using the output of class discussions, students develop their epistemic agency for using evidence from analytics tools to make progress.

6. Limitations and Further Research

The limitations of this study should be noted, as they point to areas for future research. The framework captured some central aspects of KB in response to a limited set of questions for practical use. However, this study did not measure how comprehensive these questions were, and identifying a more complete set of questions depends on further classroom experimentation. In accordance with the principles of design-based research on KB, further research should be done, for example, on the relationship between individual and collective work. These investigations may help inform and enrich knowledge-building theory.

This study demonstrated how the KCA could be used to analyze nine selected KF databases, thereby highlighting a range of issues concerning conceptual development and curriculum design. This study focused on the validation of the KCA, but further research is needed on how the KCA can be used by students with teachers of different disciplines. Moreover, to validate and examine the theoretical and design implications, additional tests of KCA use with students in various types of classrooms are needed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.v.A.; C.C. and Y.Y.; methodology, Y.Y.; software, J.v.A.; validation, Y.Y. and J.v.A.; formal analysis, Y.Y.; investigation, Y.Y.; resources, C.C.; data curation, C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y. and J.v.A.; writing—review and editing, J.v.A. and C.C; visualization, J.v.A. and C.C.; supervision, J.v.A.; project administration, Y.Y.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. and J.v.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by Open Fund of Hubei Research Center for Educational Informationization, Central China Normal University. This research was funded by University Grants Committee, Research Grant Council of Hong Kong, grant number 752508H.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Hong Kong, and approved by Human Research Ethics Committee for Non-Clinical Faculties of University of Hong Kong (EA301213, 7 January 2014).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data samples and detailed coding procedures can be accessed by contacting the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hew, K.F.; Cheung, W.S. Student Participation in Online Discussions: Challenges, Solutions, and Future Research; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.-S.; Hong, Z.-R.; Lawrenz, F. Promoting and scaffolding argumentation through reflective asynchronous discussions. Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; van Aalst, J.; Chan, C.K.K. Dynamics of reflective assessment and knowledge building for academically low-achieving students. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2020, 57, 1241–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hewitt, J. Toward an Understanding of How Threads Die in Asynchronous Computer Conferences. J. Learn. Sci. 2005, 14, 567–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardamalia, M.; Bereiter, C. Knowledge building: Theory, pedagogy, and technology. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences; Sawyer, R.L., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Scardamalia, M.; Bereiter, C. Knowledge building and knowledge creation: Theory, pedagogy, and technology. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences, 2nd ed.; Sawyer, R.K., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 397–417. [Google Scholar]

- Crescenzi-Lanna, L. Multimodal Learning Analytics research with young children: A systematic review. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 1485–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shum, S.B.; Ferguson, R. Social learning analytics. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2012, 15, 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Siemens, G.; Gasevic, D.; Haythornthwaite, C.; Dawson, S.; Shum, S.B.; Ferguson, R.; Duval, E.; Verbert, K.; Baker, R.S.J.D. Open Learning Analytics: An Integrated & Modularized Platform; Society for Learning Analytics Research: Upstate, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gašević, D.; Kovanović, V.; Joksimović, S. Piecing the learning analytics puzzle: A consolidated model of a field of research and practice. Learn. Res. Pr. 2017, 3, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siemens, G.; Baker, R.S. Learning analytics and educational data mining: Towards communication and collaboration. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 29 April–29 May 2012; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 252–254. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, C.; Siemens, G.; Wise, A.; Gasevic, D. Handbook of Learning Analytics; SOLAR: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://circlcenter.org/handbook-of-learning-analytics/ (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Chen, B.; Zhang, J. Analytics for Knowledge Creation: Towards Epistemic Agency and Design-Mode Thinking. J. Learn. Anal. 2016, 3, 139–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsai, Y.-S.; Rates, D.; Moreno-Marcos, P.M.; Muñoz-Merino, P.J.; Jivet, I.; Scheffel, M.; Drachsler, H.; Kloos, C.D.; Gasevic, D. Learning analytics in European higher education—Trends and barriers. Comput. Educ. 2020, 155, 103933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herodotou, C.; Rienties, B.; Boroowa, A.; Zdrahal, Z.; Hlosta, M. A large-scale implementation of predictive learning analytics in higher education: The teachers’ role and perspective. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2019, 67, 1273–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matcha, W.; Uzir, N.A.; Gasevic, D.; Pardo, A. A Systematic Review of Empirical Studies on Learning Analytics Dashboards: A Self-Regulated Learning Perspective. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2019, 13, 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschmann, T. Dewey’s contribution to the foundations of CSCL research. In Proceedings of CSCL 2002: Foundations for a CSCL Community; Stahl, G., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Suthers, D.D. Technology affordances for intersubjective meaning making: A research agenda for CSCL. Int. J. Comput. Collab. Learn. 2006, 1, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wise, A.F.; Hausknecht, S.N.; Zhao, Y. Attending to others’ posts in asynchronous discussions: Learners’ online “listening” and its relationship to speaking. Int. J. Comput. Supported Collab. Learn. 2014, 9, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, A.F.; Speer, J.; Marbouti, F.; Hsiao, Y.-T. Broadening the notion of participation in online discussions: Examining patterns in learners’ online listening behaviors. Instr. Sci. 2012, 41, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, V.L.; Hewitt, J. An investigation of student practices in asynchronous computer conferencing courses. Comput. Educ. 2010, 54, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, E.; Jones, A.; Barker, P.; Van Schaik, P. Using e-learning dialogues in higher education. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2004, 41, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkarainen, K.; Lipponen, L.; Jarvela, S. Epistemology of Inquiry and Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning. In CSCL 2: Carrying Forward the Conversation; Koschmann, T., Hall, R., Miyake, N., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 11–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner, P.A.; Kreijns, K.; Phielix, C.; Fransen, J. Awareness of cognitive and social behaviour in a CSCL environment. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2015, 31, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hew, K.F.; Cheung, W.S.; Ng, C.S.L. Student contribution in asynchronous online discussion: A review of the research and empirical exploration. Instr. Sci. 2010, 38, 571–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardmalia, M. Collective cognitive responsibility for the advancement of knowledge. In Liberal Education in a Knowledge Society; Smith, B., Ed.; Open Court: Chicago, IL, USA, 2002; pp. 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Tao, D.; Chen, M.-H.; Sun, Y.; Judson, D.; Naqvi, S. Co-Organizing the Collective Journey of Inquiry with Idea Thread Mapper. J. Learn. Sci. 2018, 27, 390–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, B.; Hong, H.-Y. Schools as Knowledge-Building Organizations: Thirty Years of Design Research. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 51, 266–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Du, Y.; van Aalst, J.; Sun, D.; Ouyang, F. Self-directed reflective assessment for collective empowerment among pre-service teachers. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 1960–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, J.; Oshima, R.; Matsuzawa, Y. Knowledge Building Discourse Explorer: A social network analysis application for knowledge building discourse. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2012, 60, 903–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplovs, C. Visualization of Knowledge Spaces to Enable Concurrent, Embedded and Transformative Input to Knowledge Building Processes. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2010. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Van Aalst, J.; Chan, C.K.K. Student-directed assessment of knowledge building using electronic portfolios. J. Learn. Sci. 2007, 16, 175–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Philip, L.; Siemens, G.; Conole, G.; Gašević, D. In Proceedings of the 1st International Confer-ence on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (LAK11), Banff, AB, Canada, 27 February–1 March 2011; ACM: New York, NY, USA.

- Burtis, J. Analytic Toolkit for Knowledge Forum; Centre for Applied Cognitive Science; The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Scardamalia, M.; Reeve, R.; Messina, R. Designs for collective cogniitve responsibility in knowledge-building communities. J. Learn. Sci. 2009, 18, 7–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Scardamalia, M.; Bereiter, C. Advancing knowledge-building discourse through judgments of promising ideas. Int. J. Comput. Collab. Learn. 2015, 10, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bransford, J.D.; Brown, A.L.; Cocking, R.R. How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; van Aalst, J.; Chan, C.K.K.; Tian, W. Reflective assessment in knowledge building by students with low academic achievement. Int. J. Comput. Supported Collab. Learn. 2016, 11, 281–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Aalst, J.; Chan, C.; Tian, S.W.; Teplovs, C.; Chan, Y.Y.; Wan, W.-S. The Knowledge Connections Analyzer. The future of learning. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference of the Learning Sciences (ICLS 2012); Short Papers, Symposia, and Abstracts; Van Aalst, J., Thompson, K., Jacobson, M.J., Reimann, P., Eds.; ISLS: Sydney, Australia, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 361–365. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, H.; van Aalst, J. Participation in Knowledge-Building Discourse: An Analysis of Online Discussions in Mainstream and Honors Social Studies Courses. Can. J. Learn. Technol. 2009. Available online: http://www.cjlt.ca/index.php/cjlt/article/view/515 (accessed on 3 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.Y.; Chan, C.K.K.; van Aalst, J. Students assessing their own collaborative knowledge building. Int. J. Comput. Supported Collab. Learn. 2006, 1, 277–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aalst, J. Distinguishing knowledge sharing, construction, and creation discourses. Int. J. Comput. Supported Collab. Learn. 2009, 4, 259–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stahl, G. Group cognition as a foundation for the new science of learning. In The New Science of Learning: Cognition, Computers and Collaboration in Education; Khine, M.S., Saleh, I.M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pryor, R.W. Multiphysics Modeling Using COMSOL 5 and MATLA; David Pallai: Dulles, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- NRC. Next Generation Science Standards for States, by States; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).