Abstract

This study examines whether the designation as the most admired firms affects firms’ tax management behavior. Based on 6880 Korean firms from 2014 to 2018, we regressed to analyze the relationship between the designation as the most admired firms and tax avoidance. Designation as the most admired firm is considered to result in a high reputation, and reputation is one of the intangible assets when assessing the firm value. We found that the firms designated as the most admired firms are reluctant to avoid taxes. Reputable firms are expected to be consistent with their fame. Therefore, those firms are less engaged in unethical or immoral tax avoidance. We also found a positive effect of the index for environmental, social, and governance on the relationship between the designation as the most admired firms and tax avoidance. Environmental, social, and governance activities are the managements’ choice and are a part of corporate activities, whereas firms’ reputations result from enterprise-wide activities. The findings suggest that the designation as the most admired firms with regard to environmental, social, and governance activities is considered highly reputable and results in deciding to improve corporate sustainability in tax management. The relationship between the designation as the most admired firms and tax avoidance is strengthened in an information environment where the firms are Chaebol-affiliated and in high information asymmetry.

1. Introduction

Reputable firms carry the information that they are competent and conduct good business in compliance with shareholder interest. Reputable firms are regarded as having superior management quality with superior and innovative capabilities and whose employees are talented and ethical. In accounting studies, the firm’s reputation is regarded as an intangible asset that affects the generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) and tax accounting [1]. They suggest that when a company gains social sympathy for committing and fulfilling its ethical obligation in good faith, it is profitable to offset the costs already used [1]. However, measuring or observing a firm’s reputation is hard but worth it. Thus, a sophisticated and sufficient evaluation system is necessary to develop evaluation indicators for monitoring the firms with good management.

In this study, we use the integrated evaluation index of the firms suggested by Korea’s Management Associate Consulting (KMAC) that ranks the Korean firms by the degree of admiration. It is called the KMAC index, evaluated by the survey from executives in each industry, financial analysts, and general consumers. The KMAC index’s information is publicly available and aggregates employees, shareholders, society, and image and creative ability values. When the firms are designated as the most admired firms, the firms receive a reputation in the market, and it will bring competitive benefits, such as reducing debt financing costs [2] and enhancing the company’s visibility. It also lowers the possibility of misstating financial statements, implying the high quality of earnings. Thus, if firms acquire a reputation by being designated as the most admired firms, they will continue to maintain their reputation in a certain period and continue to exist in a market by inducing investments, allowing for higher prices [3].

The reputation affects the management’s decisions to take steps to provide long-term benefits, such as corporate’s sustainable existence rather than short-term interests [4]. Highly reputable firms strive to increase shareholders’ wealth by focusing on qualitative products and innovative processes [5]. Therefore, reputable firms have greater incentives to protect their reputation from behaving differently than other companies.

In our study, we focus on the reputational effect in the view of tax management. Paying taxes is an indispensable element of an organization’s operation, but incurs the direct cash outflow, which can burden the firms. Almost all firms are aiming at maximizing accounting profit to ensure a sustainable existence. For the managers seeking sustainable existence by maximizing firm value, planning for taxes could be the answer [6]. In addition, tax management is viewed as a long-term investment and allocates limited resources toward income-generating investments. If firms manage taxes effectively, the firm is expected to have transparent accounting information, alleviate information asymmetry, and spread the social trust that they are paying their fair share [7].

In our study, we relate the designation as the most admired firms to tax management. Designated as the most admired firms means that the firm has earned the reputation, which enables sustainable management that will increase the firms’ sustainable existence. Reputable firms focus on the values of shareholder, employee, customer, and social-based innovative processes to create an image that will increase brand value. The information on firms’ reputation is helpful to the public and updated every year, so the level of information asymmetry will decrease. Public attention rising from the reputation will yield transparent financial information [4], and reputable firms are eager to maintain their fame and provide high-quality financial information. Thus, we expect that the designation as the most admired firms is related to tax management.

Moreover, our study examines ESG (Environment, Social, and Governance) impact on whether reputable firms are likely to manage taxes. Investment in ESG can enhance a company’s reputation and maximize stakeholders’ trust, positively impacting the corporate value in the long run. If companies value reputation, management avoids potentially unethical behavior [8]. In addition, those companies are likely to maintain their existing reputation or gain a better reputation [9].

Using 6880 admired firms of the Korea Stock Exchange Market, we found that the firms designated as the most admired are low in tax avoidance. The result indicates that reputable firms have a tendency to keep their reputation as it is, thus reducing tax avoidance behavior. Moreover, our findings imply that ESG plays a positive role in the relationship between the designation as the most admired firms and tax avoidance. Similar to corporate social responsibilities, ESG is considered a shared belief within an organization regarding legitimate corporate behavioral strategies that consider the economic, cultural, environmental, and other external implications of corporate behavior [10]. Thus, firms participating in ESG are considered as having desirable corporate culture and shared beliefs and can fulfill honest tax payments, which is one of the elements of social responsibility.

Our study has a distinct contribution. We are the first to examine the direct effect of reputation on tax behavior in the Korean market setting. The firms’ reputation is considered as an intangible asset and affects future taxation behavior. That is, reputation affects non-tax costs and actual cash out concerning the value of a firm, implying a sustainable existence in a market. At the same time, the data for the most admired company is based on survey results from the one of the prestigious organizations, KMAC, established in 1989. It has lead the management innovation of South Korea and pays a great role as a knowledge provider that provides the highest management services as a reliable partner and contributes to the implementation of a firm that creates value. The announcement of the most admired companies evaluates and guides society and stakeholders in the direction of which firm should be aimed for.

2. Backgrounds and Hypotheses

2.1. Designation as the Most Admired Firms

Being selected as the most admired firms is the management’s new paradigm that spreads all over the world. The Fortune’s America’s Most Admired Companies (AMAC) is widely used to measure firms’ reputation. Since the list is independent, available to the public, and covers a wide range of companies and industries, it is by far the most representative when measuring reputation [2,4,11,12,13]. Firms with the highest scores are considered highly reputable [4].

In South Korea, KMAC consulting is the only research institute in the field of respected firms. KMAC consulting developed a research model that comprehensively evaluates the values of the entire firm since 2004. The KMAC is about acquiring excellent competitiveness confirmed through continuous innovative activities. It is the driving force for achieving excellent management results as an important success factor that discriminates against other companies based on its innovative ability to flexibly respond to changes in the business environment and lead the business environment.

Table 1 below is the evaluation criteria suggested by KMAC consulting. As shown in Table 1, the candidate companies are selected based on market size by industry and industrial competition. The survey is conducted using the Internet, interviews, telephone calls, and faxes so that a more accurate survey could be conducted in consideration of the situation of the survey subjects. In the case of an industry-specific survey, where more expert and accurate surveys are needed, the executives and analysts are surveyed. Doing so brings a correct understanding and interest in corporate activities to consumers and several other stakeholders by providing directions on what companies will be respected. By recognizing the company’s current position, it seeks to company’s development and presents the direction of enterprise-wide technological innovation under a new paradigm.

Table 1.

Investigation method.

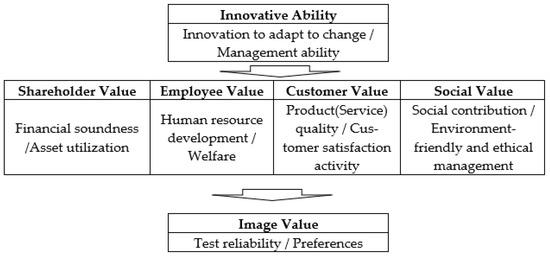

Figure 1 shows the modified figure from the KMAC consulting homepage, which displays criteria used for KMAC consulting. The most admired firms’ criteria are the six core values of shareholders, employees, customers, social, and image. With an innovative ability as a base, the values of shareholders, employees, customers, and social are integrated into image value. Then, the values are integrated to calculate and announce index for KMAC. Finally, the survey results are converted to the scores, and these scores are the rankings of admired companies.

Figure 1.

Investigation criteria. (Source: Korea Most Admired Companies Consulting [14]).

Selected as being admired can be viewed as a process of acquiring a reputation. Barnett et al. (2006) [15], Cao et al. (2012) [4], and Cao et al. (2015) [2] provide the theoretical framework of reputation and postulate that reputation is comprised of collective assessments based on a firm’s long-term behavior. The reputation is higher than a favorable feeling and takes a long time to form trust, confidence, and support [16]. In general, the reputation, once settled, has characteristics that do not change easily [17]. The firms with higher reputations are considered accountable, credible, and trustworthy [18]. In addition, reputation is one of the intangible assets that are difficult to copy, making it a sustainable competitive advantage [19]. Reputation is vital for the future of industry as companies need to be differentiated when selling their products. Reputable companies concentrate on innovation and product quality to elevate value [5] for their sustainable existence.

According to the agency theory, reputable firms are expected to reduce information asymmetry among the firms’ stakeholders [5] because those firms focus on product quality and innovative processes. Reputable firms increase the transparency of the firm’s information environment, and reinforce accounting information accuracy and quality.

Several studies are showing that the reputation, measured as the most admired firms, show the excellent investment performance. Antunovich and Laster (2003) [12] examine the relationship between the firms with the rankings from Most Admired Companies from Fortune in the U.S. on stock price in a market. The result shows that the firms with the highest scores on the Most Admired Companies are superior to the firms with low scores. Lee and Kim [20] finds the positive effect of the admired firms on the firm value. These positive scores of the admired firms can be interpreted as being related to the value to the company beyond providing financial information. The non-financial components of these companies’ reputation scores can be the evidence of intangible assets, explaining corporate value.

Reputation also has significant impacts on the market [2]. First, the firms with good reputations mean the firms with a high level of understanding for the distribution of quality and capabilities and business performance consistent with shareholders. In other words, reputation means that the firms have high-quality management with talented employees and technological innovation, and the factors are value-relevant but difficult to observe. Second, reputation ranking attracts social attention through media. As the firm attracts attention, its stock is of interest to investors, yielding a low equity cost. Firms’ reputation also means high-quality financial reports [4], reducing information asymmetry [21]. Information asymmetry reduction lowers the firm’s cost of equity.

2.2. Tax Management

Taxes are forcibly collection from the firms rather than voluntarily. Tax collection from the public is used for financing public expenditure, such as investing in infrastructure, education, and health, regulating social and economic behavior, and redistributing wealth [22]. Though imposing taxes is inevitable, managing taxes is essential for growth and sustainable development. Hilling and Ostas (2017) [22] define two ways of managing tax, and they are mitigation and avoidance. Tax mitigation and tax avoidance are in common in that they reduce taxes and are within the law. However, the former incur within the boundary of government intention, while the latter deviates from the intention.

In this study, we focus on tax management in the aspect of tax avoidance. If firms are involved in tax avoidance, there might be an opportunistic behavior that entails direct costs, such as implementation and reputation costs from punishment [23]. In other words, firms being involved in less tax avoidance not only means a low possibility of managerial opportunism, but also increases the transparency and reliability of accounting information, which will increase firm value [24,25].

Studies have examined the factors affecting tax avoidance. Ki [26] found a negative association between corporate social responsibilities (CSR) activities and tax avoidance. As the firms invest in CSR activities, there is a low possibility of avoiding taxes. Kim and Kwon [27] examined the effects of CSR activities and the independence of audit committees on tax avoidance. They report that firms that participated in CSR are more likely to avoid taxes than matching firms, indicating that CSR is an effective tax strategy. Armstrong et al. (2016) [28] reported that in a group with high tax avoidance, the firms with the board with financial expertise and independence less likely avoid tax. The result indicates that good governance reduces the likelihood of avoiding taxes. Gallemore and Labro (2015) [29] examined the internal control on tax avoidance. Internal control plays a critical role in tax management. Internal control and the ability to monitor management behavior can help ensure the establishment of effective tax planning that can be enforced at the enterprise-wide level. By improving the timeliness and reliability of the financial information, effective internal control reduces the tax risk. Khurana et al. (2018) [30] investigate tax avoidance in accordance with managerial ability. They define managerial ability as the ability to convert corporate resources for profit, and managers with high capabilities will efficiently allocate the limited resources within the firm to obtain maximum profit. Managers with high abilities will consider tax avoidance as the factor for reducing firm value. Thus, highly capable managers will try to make tax plan to decrease tax avoidance to increase firm value. To sum up, the tax avoidance level lowers depending on the propensity and strategic choice of the firm, which will guide the firm value increment.

There are prior studies that have examined the consequences of tax management. Hanlon and Slemrod (2009) [31] and Lee and Jung (2008) [32] showed the market reaction in accordance with the tax avoidance. Both the research suggested that less tax avoidance impact stock market positively. Balakrshman et al. (2014) [33] reported the firms with low tax avoidance will increase corporate transparency. Low tax avoidance means that the firms’ accounting procedures and environment are traceable and transparent. Improved firms’ transparency will increase firm value by reducing the information asymmetry among stakeholders, increasing capital market efficiency, reducing the investment uncertainty and reducing the cost of capital. Kang (2019) [6] examined the association between tax avoidance and corporate transparency. The result suggests that the firms involved less in tax avoidance have increased transparency, which plays a vital role in reducing information asymmetry among shareholders, improving capital market efficiency, reducing investment uncertainty, and reducing the cost of capital. Corporate transparency is also associated with preventing corruption, reducing the risks related to shareholder wealth. Chun et al. (2020) [34] examined the effect of tax avoidance on the cost of equity capital in accordance with the level of the legal environment. They found that the firms in a strong legal environment make tax plans positively incremental to firm value, while the firms in a weak environment use tax avoidance to exploit their personal benefits, yielding high equity risk premiums.

2.3. Hypothesis Development

Thanks to the development of the Internet and social networks, the impact of corporate image on profitability has increased more than in the past. Achieving a high reputation of the company is a gradual process, and overall assessment is built over a long period. It is difficult to copy, but sustainability and competitiveness are earned once a reputation is achieved [19]. When a firm gains a reputation, it may enjoy the benefits and impact the market positively (Cao et al., 2015) [2], such as low cost of capital, high-quality management (Khurana et al., 2018) [30], and higher financial reporting quality (Cao et al., 2012 [4]).

In the field of accounting study, whether the firm is reputable or not is measured by the scores in KMAC’s index of the most admired firms in South Korea, where the higher the score the better reputation. Being admired implies that the firms are noticeable and visible in the market. Therefore, according to agency theory, reputable firms are recognizable by the investors and stakeholders. In addition, the theory suggests that reputable firms are expected to reduce information asymmetry among the firms’ stakeholders (Kim et al., 2020 [5]), because those firms signal that they focus on product quality and innovative processes. Thus, reputable firms increase the firms’ information environment’s transparency and reinforce accounting information accuracy and quality.

Firms are the groups for pursuing the maximization of corporate value. Thus, there is a great deal of incentive to minimize actual cash out, such as corporate tax costs. Managing taxes as a strategy to reduce explicit or implicit tax burden enhances the firm value and relates to firms’ sustainability [35]. Firms sustainably managing taxes are willing to contribute their fair share so that the government can earn adequate tax revenue. In this study, we focus on tax avoidance as a tool for measuring tax management. Tax avoidance is within the boundary of legality, but it can be viewed as unethical or immoral [22]. If firms are less likely to engage in tax avoidance, their existence will be sustained in the long run [36]. In addition, firms involved in tax avoidance are labeled as poor corporate citizens, negatively affecting sales [37]. For example, in early 2000, several firms in the U.S. moved their headquarters to tax havens, saving huge costs on taxes. However, even though the firms save taxes, they experienced a stock crash afterwards [38]. This means that such firms have been able to save huge taxes, but the firms are accused of being unpatriotic in the media, and the stock has fallen sharply due to these effects. In 2012, Starbucks did not pay any corporate tax in the U.K. despite the huge increase in sales. Negative public opinion caused a boycott against Starbucks stores, a significant decline in corporate reputation, and the closure of many stores [39]. Even though Starbucks claimed to be compliant with British tax law, reputational damage caused Starbucks to pay tax voluntarily afterward.

According to game theory, fame is regarded as a distinctive characteristic or a signal that an organization establishes a competitive advantage. In a repeated game where one player has private information about the type, other players use the players’ reputation to form their own beliefs and choose their decision strategically to maximize their future benefits. It is called the reputation effect, which reduces agency problems [2]. The consumers are likely to rely on the reputation since the consumers are the ones who have less information than managers. Similarly, outside investors lack information than managers about the firms’ future action, so a good corporate reputation will allow management to act in ways consistent with fame. Players with a certain level of reputation have an incentive to offset the immediate consequences of the current decision with the long-term impact of reputation [18]. Firms with reputations are reluctant to engage in activities that may affect the firm’s reputation negatively. Therefore, highly reputable firms may take steps to protect their reputation by not participating in aggressive tax planning. Thus, we conjecture our first hypothesis as follows.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The firms designated as the most admired firms are less likely to avoid taxes.

With the digitalized environment, information such as corporate immoral management activities and negative results of companies is quickly transmitted to consumers worldwide, which not only reduces the sales of the companies but also has a fatal effect on the companies’ reputation. In addition, global companies recognize that it is an era in which the company’s survival is threatened if problems such as ethics, environment, and labor occur in corporate activities. Thus, concern for Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG) is more than emphasized.

ESG is an extension of corporate social responsibility (CSR), and there are two different perspectives regarding CSR [40]. First, CSR is viewed as philanthropic and ethical, and it is firm-value neutral and enhances brand value and reputation. In this view, participating in CSR activities can increase long-term corporate value resulting from increased sales, secure human resources, and strengthening the corporate image. ESG activities are believed to be an organization’s shared belief that considers the economic, social environment and other external impacts of corporate behavior [10]. Hoi et al. (2013) [10] suggest that the firms with CSR activities are regarded as taking long-term profits by building a positive image, and those firms are reluctant to avoid taxes because of the negative image that it might bring. Thus, ESG motivates the firm to maintain the value of admiration and is likely to forgo excessive tax.

The other perspective is the opportunistic point of view. The opportunistic perspective is that CSR is conducted in a short period of time to support management decisions. In addition, it is used as a means to achieve the private interest of managers, hindering the interests of shareholders and often results in degrading corporate performance [41]. In this view, aggressive tax avoidance may damage the reputation of companies and business owners and impose potential fines by the tax authorities [42]. As a part of managing risk, the firm can use ESG activities opportunistically as a pre-defense mechanism against the punishment in the event of a negative incident. Davis et al. (2016) [43] concluded that CSR activities are considered a tool for building positive image, but firms that actively avoid taxes carry out CSR activities to offset their negative image. Lennox et al. (2013) [44] found that the firms accused by the SEC of fraudulent accounting had less tax avoidance. This shows that aggressive financial reporting is a more strategic choice of the company, which indicates that such companies have avoided fewer taxes to hide their choices.

In the case of a company that is actively engaged in CSR, if the tax authorities confirm the fact of tax evasion due to tax avoidance, the impact on stakeholders with various investors may significantly damage the corporate image. On the other hand, in the case of companies that do not, even if the tax authorities reveal the tax evasion due to tax avoidance, it can be expected that the impact will be less than that of companies that are active in CSR [45]. Hilling and Ostas (2017) [22] argue that firms should comply with tax laws and resist the temptation to take advantage of loopholes, ambiguities, and flaws in legal texts. Taking those perspectives together, we attempt to analyze whether the firms designated as the most admired firms with ESG negatively affect tax avoidance, and we build our second hypothesis as follows.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Firms that are designated as admired firms and who engage in ESG are less likely to avoid taxes.

3. Research Design and Sample Description

3.1. Measuring Tax Avoidance

To measure tax avoidance, we use the book-tax difference (BTD), the difference between the financial income and taxable income suggested by Desai and Dharmapala (2006) [36]. Because BTD occurs either due to tax avoidance or earnings management, the estimated residual amount after eliminating earnings management is used. It means that the remaining portion of the difference between financial income and taxable income that includes the profit adjustment portion and is not explained in the total accrual amount is due to the tax avoidance tendency. The following is the process of estimating tax avoidance. Firm’s tax profit is calculated based on the corporate tax burden available from the financial statements. In detail, the corporate tax burden is the sum of tax expense, deferred tax expense at the end of the current year, and deferred income tax liabilities at the end of the prior year, after subtracting deferred income tax at the end of the prior year and deferred income tax liabilities at the end of the current year. Then the corporate tax burden is divided by the corporate tax rate to measure the estimated taxable profit as follows:

where, tax burden = corporate tax burden; rate = corporate tax rate; and = estimated taxable profit. The corporate tax rate we use is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The corporate tax rate in accordance with tax base.

We use firms with positive estimated taxable profit calculated based on Equation (1) as our sample because the firms with negative estimated taxable profits have no incentive to avoid tax. Then, we deducted the taxable profit estimated from the income before corporate tax deduction used for the profit in the financial reporting as follows:

where Diff1 = difference between income before corporate tax deduction and estimated taxable profit; Before = income before corporate tax deduction; and = estimated taxable profit.

The difference between income before corporate tax and taxable profit may include tax avoidance actions and earnings management to increase accounting profits, so the management’s adjustment behavior should be eliminated from the difference. As a proxy for earnings management, the total accruals or managers’ discretionary accruals are used. In our study, the difference between financial income and taxable income that is not explained in the total amount generated is regarded as tax avoidance.

where Diff2 = Diff1/total assets; TA = Total accruals (Net income—CF from operation)/total assets; and = residual for the firm

In this study, we extracted the residuals after regression analysis by year-industry as follows:

where, TaxAvoid = Tax avoidance and = residual from Equation (3)

The estimated residuals were considered as tax avoidance as the portion of the difference between financial income and taxable income that is not explained in total accruals [36].

3.2. Research Model

To test the relationship between designation as the most admired firms and tax avoidance, the following regression models are used. The first model examines the first hypothesis of the KMAC effect on tax avoidance:

where, TaxAvoid = tax avoidance measure; Admiration = natural logarithm score of admired firms; Big4 = if firm is audited by Big4 and 0 otherwise; Fo = percentage of shares held by foreign investors; Mo = percentage of shares held by the largest shareholder; Loss = 1 if a company with loss, and 0 otherwise; Size = natural logarithm of total assets; Lev = total debt divided by total assets; Beta = estimated value of beta, the number of months for five years before the relevant year to control the systematic risk; Vol = volatility of stock; Roa = net income/total assets; Mtb = market value of equity/book value of equity; IND dummy = industry dummies; YR dummy = year dummies.

Based on the prior research, firm size and financial leverage are included to minimize the possible bias. Size, as a proxy for firm size, is measured as the natural log of total assets. For measuring firm performance and risk, Roa and Loss are included, respectively. For controlling volatility within a particular year arise from a specific economic situation, year dummies are included in the model. To control the effect of a specific industry, industry dummies are included in the model.

3.3. Sample Selection

Table 3 shows the data process for our analysis. Our sample includes all the firms listed in the Korean Stock Exchange with December year-end data from 2014 to 2018. For the admired firms, we manually collected the data from KMAC consulting. For the firms’ financial data as control variables, we use the FnGuide database. Firms without incomplete data are eliminated for our analysis. We winsorize the top and bottom 1% of the control variables to minimize the outlier effect. After all these procedures, we get 6880 firm-year observations.

Table 3.

The data selection process.

Table 4 shows the data distribution by year. It shows that the observation gradually increases by the year. Table 5 displays the sample distribution by industry, and it shows that the data is distributed over the industries.

Table 4.

Sample distribution by year.

Table 5.

Sample distribution by industry.

4. Result and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 6 shows the descriptive statistics of the main variables used in this study. Tax avoidance’s mean value is −0.0236, and its median is −0.0118. The mean (median) value of Admiration is 1.871. The mean value of ESG is 4.3893 and its median is 4.4308.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 7 shows the Pearson correlation matrix for this study’s main variables. The result shows that designation as the most admired firms are positively related to tax avoidance. This means that this simple relationship does not support our hypothesis. However, this correlation test is the univariate analysis with the limitation that this analysis does not consider the other influences of control variables.

Table 7.

Pearson correlation.

4.2. Main Results and Discussion

Table 8 describes the regression results on the designation as the most admired firms’ tendency of tax avoidance, testing our first hypothesis. The coefficient of the admired firms is −0.012, and it is significant at 1% level. This analysis result is that admired firms are less likely involved in tax avoidance.

Table 8.

The regression result on the relationship between the designation as the most admired firms and tax avoidance.

We interpret our result as follows. Designated as the most admired firms means that the firms have achieved reputation and are expected to have transparent, accountable, credible, and sustainable management, operating with excellence [18]. Acquiring a reputation in the market is a gradual process, building over a long period of time. Once reputation is achieved, it means that the firm has gained the power of sustainability and competitiveness [19]. As we examine whether reputable firms are less likely to avoid tax, we found that reputable firms are reluctant to avoid tax. That is, reputable firms are expected to be consistent with the fame. In other words, reputable firms have an incentive to sustain their status as being admired and consider long-term effects on the reputation (Cao et al., 2012) [4] against instant consequences.

There is a common belief that managers want to minimize taxes in order to maximize profit. In the course of achieving maximum profit, firms may be allured by reducing actual cash spending in the form of paying tax. Paying tax is regarded as paying a fair share. In other words, failure to pay the appropriate tax amount is viewed as a poor corporate citizen [37], negatively affecting the reputation. Once a reputation is collapsed, it is hard to rebuild or takes a long period of time.

The result is in line with the prior research. For example, Kim et al. (2020) [5] suggest that the company reputation reduces information asymmetry, leading to decrease the cost of capital. Cao et al. (2012) [4] assert that higher reputation influences audit fee that leads to higher financial reporting, implying that reputable firms are willing to pay higher audit fees to keep or increase their financial reporting quality as a means to maintain their fame. It is significant that our study evaluates the firms’ sustainability, measured by tax avoidance in relation to one of the factors that affect the information environment. Therefore, our result is consistent as we hypothesize that designated as the most admired firms are reluctant to avoid tax.

Table 9 displays the result of the second hypothesis and the effect of ESG on the relationship between the designation as the most admired firms and tax avoidance. The coefficient of the interaction term between the designation as the most admired firms and ESG is −0.017 and significant at a 5% level. Thus, our result is consistent with the second hypothesis.

Table 9.

The effect of ESG on the relationship between the designation as the most admired firms and tax avoidance.

Firms with ESG mean that the firms care about economic, social, and environment activities for sustainable existence. Firms that engage in ESG activities fulfill sincere tax payments as one of the elements of social responsibility. We confirm that reputable firms engaged in ESG are likely to forgo aggressive tax avoidance. By participating in ESG, firms can earn a positive investors’ attraction in the market (Lichtenstein et al., 2004) [47] and competitiveness in the market (Schuler 2006) [48] with their transparent management (Eccles et al., 2011) [49], thus earning a better reputation. The admired firms doubled up with ESG participation may keep their reputation in the market, and they want to keep their reputation or fulfill their role as members of society. Therefore, firms designated as the most admired, with ESG participation, are less likely to avoid taxes.

Based on the results of our study, it can be expected that the tax authorities can utilize the firms’ transparency and sustainability as a preliminary measure of the tax avoidance level. Our results provide meaningful implications for tax authorities, regulators, management, and investors by presenting the possibility that it can be used as a policy measure to prevent firms’ excessive tax avoidance even without amendments to tax laws.

4.3. Additional Analysis—The Effect of Corporate Governance

Table 10 shows the effect of Chaebol on the relationship between the designation as the most admired firms and tax avoidance. The coefficient of the interaction variable is −0.024, significant at 5%. Chaebol is a unique mode of governance in South Korea economy. Chaebol is a conglomerate company that has driven the rapid growth of the Korean economy in the past. Chaebol exercises strong control over the entire corporate group with relatively few shares, discriminatory from non-Chaebol companies. In the case of conglomerate companies, management decisions are likely made in the direction of increasing corporate value from a long-term perspective rather than short-term corporate performance [50].

Table 10.

Effect of Chaebol on the association between the designation as the most admired firms and tax avoidance.

Our result suggests that when Chaebol is designated, the most admired firms are not likely to avoid tax. The adverse effects of tax avoidance, such as damaging corporate value and reputation, cannot be ignored since conglomerates are the groups interested in the firm’s sustainable existence in the long term [23].

4.4. Additional Analysis—The Effect of the Information Environment

Table 11 shows the result of testing whether the designation as the most admired firm makes companies less likely to avoid taxes depending on information asymmetry. IA stands for information asymmetry. The coefficient of Respected IA is −0.014, significant at 1%. Our result suggests that the most admired firms in the market with information asymmetry are not likely to avoid taxes.

Table 11.

Effect of information asymmetry on the association between the designation as the most admired firms and tax avoidance.

Iormation asymmetry is an inefficient problem that leads to lowering corporate value. The firms with high information asymmetry monopolize the information resulting in opportunistic behavior [51]. However, we can interpret that the designation as the most admired firms carries the information that the firm is transparent with high competency in their business. A firm’s good reputation is calculated by aggregating the values of employees, customers, and innovation. In other words, being selected as one of the most admired firms will improve transparency and the company’s image and eliminate information uncertainty, which is effective where information asymmetry is high. Our result is supported by the study of Cao et al. (2015) [2], which suggests that reputable companies reduce their information asymmetry. In their study, companies listed in the most admired firms are considered reputable. Reputable firms mean a firm’s ability and dedication to work to benefit shareholders [2].

5. Conclusions

Designation as the most admired firm means that the firms create excellent management results based on the excellent competitiveness confirmed through continuous technological innovation activities. To be designated as one of the most admired firms, the intangible assets such as the innovative ability, values of shareholders, employees, customers, society, and image should be integrated and superior to non-designated firms.

Our study examines whether the designation as the most admired firms have tendency to avoid taxes as a proxy for tax management. After a regression analysis using 6880 Korean firms, we found that the admired firms are less likely to avoid taxes. Designation as one of the most admired firms means the formation of a certain reputation, and once the reputation is formed, it does not change easily, and the firms make an effort to keep their reputation (Oh and Kang 2010) [17], represents firms’ sustainability, containing the future growth and financial performance [2]. Thus, reputable firms manage taxes to pay their fair share. We also found the ESG’s positive effect on the relationship between the designation as the most admired firm and tax avoidance. Participating in ESG means that the firms want to take long-term profits by building a positive image. The firms are expected to be reluctant to avoid tax because they are afraid that aggressive tax avoidance will bring the negative image to the public. We tested whether the firm’s governance and information asymmetry affect the relationship between the designation as the most admired firms and tax avoidance.

Our study has a contribution and a limitation. First, a firms’ reputation is considered as an intangible asset and affects future taxation behavior. That is, reputation affects non-tax costs and actual cash out concerning the value of a firm, implying sustainable existence in a market. Several studies examine the relationship between reputation and financial performances [2,5]. However, we are the first to examine the direct effect of reputation on tax behavior in the Korean market setting. Second, maintaining a good reputation shows the benefits that businesses can sustain in the future. This suggests that for a firm’s management, maintaining a good reputation is likely to sustain its reputation in the market.

However, this study has a limitation. Our study is focused on Korean firms. If the number of non-financial information expands by including non-announcement firms, the analysis will be more elaborated. Similar to Fortune, U.S., that announces the list that exceeds the 50% percentile of the companies within the firm, the data used in this study is selected based on industry and firm size. Therefore, the companies that do not satisfy the industry and sample size must be conducted on other research designs. Future research should investigate the relationship at all levels of corporate reputation. Another limitation of this study is measuring the penalty for tax avoidance. The firms with tax avoidance will be charged an actual finance cost such as an additional penalty fee on top of the original tax amount or a non-financial cost such as reputational damage. There is no publicly available data in South Korea that can measure those costs. It may be useful for future research to examine those costs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.; methodology, J.L.; software, S.K.; validation, J.L. and E.K.; formal analysis, S.K.; investigation, S.K. and E.K.; resources, E.K.; data curation, S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, S.K.; visualization, E.K.; supervision, J.L.; project administration, J.L.; funding acquisition, J.L., S.K. and E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kim, M.T.; Choi, T.H. The relationship between the level of business ethics and accounting transparency for SME and large company. Korea Int. Account. Rev. 2013, 52, 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Myers, L.A.; Myers, L.A.; Omer, T.C. Company reputation and the cost of equity capital. Rev. Account. Study 2015, 20, 42–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvard Business Review. Available online: https://hbr.org/2016/06/we-studied-38-incidents-of-ceo-bad-behavior-and-measured-their-consequences (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Cao, Y.; Myers, L.A.; Omer, T.C. Does company reputation matter for financial reporting quality? Evidence from restatements. Contemp. Account. Res. 2012, 29, 956–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Kim, J.; Kang, J. Company reputation, implied cost of capital and tax avoidance: Evidence from Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.Y. Tax avoidance and corporate transparency. Korea Assoc. Tax Account. 2019, 20, 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.S.; Kim, W.B. Study on the relation between corporate characteristics and tax avoidance: Summary of financial & non-financial characteristics. J. CEO Manag. Stud. 2018, 21, 117–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, H.J.; Choi, J.S. Corporate social responsibility and earnings management: Does the external business ethics portray internal ethics. Korean Account. Rev. 2013, 22, 257–309. [Google Scholar]

- Linthicum, C.; Reitenga, A.; Sanchez, J. Social responsibility and corporate reputation: The case of the Arthur Andersen Enron audit failure. J. Account. Public Policy 2010, 29, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoi, C.K.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, H. Is corporate social responsibility (CSR) associated with tax avoidance? Evidence from irresponsible CSR activities. Account. Rev. 2013, 88, 2025–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.W.; Dowling, G.R. Company reputation and sustained superior financial performances. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunovich, P.; Laster, D. Are good companies bad investment? J. Investig. 2003, 12, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodroof, P.J.; Deitz, G.D.; Howie, K.M.; Evans, R.D. The effect of cause-related marketing on firm value: A look at Fortunes’ most admired all-stars. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019, 47, 899–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KMAC Consulting. Available online: https://www.kmac.co.kr/certify/cert_sys01.asp (accessed on 9 July 2021).

- Barnett, M.L.; Jermier, J.M.; Lafferty, B.A. Corporate reputation: The definitional landscape. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2006, 9, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, G. Creating Corporate Reputations: Identity, Image and Performance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S.Y.; Kang, H.S. The effect of festival environmental cues and brand reputation on emotional responses and loyalty. J. Aviat. Manag. Soc. Korea 2010, 8, 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, R. Reputation in Games and Markets; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gatzert, N. The impact of corporate reputation and reputation damaging events on financial performance: Empirical evidence from the literature. Eur. Manag. J. 2015, 33, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, W. Value-relevance of corporate reputation. J. Account. Tax Audit Rev. 2015, 57, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, M.E.; Konchitchki, Y.; Landsman, W.R. Cost of capital and earnings transparency. J. Account. Econ. 2013, 55, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hilling, A.; Ostas, D.T. Corporate Taxation and Social Responsibility; Wolters Kluwer: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Cheng, Q.; Shevlin, T. Are family firms more tax aggressive than non-family firms? J. Financ. Econ. 2010, 95, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Tax Avoidance, Corporate Transparency, and Firm Value. Theses and Dissertations Texas Scholar Works. 2010, pp. 1–88. Available online: https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/ETD-UT-2010-12-2219 (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Koh, Y.S.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, W.W. A study on corporate tax avoidance. Korean J. Tax. Res. 2007, 24, 9–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ki, E.S. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on the Tax Avoidance and the Market Response to the Tax Avoidance. Korean J. Tax. Res. 2012, 29, 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.H.; Kwon, S.C. Corporate social responsibility and tax avoidance: Focusing on moderating effect of characteristics of board of directors. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 29, 291–318. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, C.; Blouin, J.; Jagolinzer, A.; Larcker, D. Corporate governance, incentives, and tax avoidance. J. Account. Econ. 2015, 60, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallemore, J.; Labro, E. The importance of the internal information environment for tax avoidance. J. Account. Econ. 2015, 60, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, I.K.; Moser, W.J.; Raman, K.K. Tax avoidance, managerial ability, and investment efficiency. A J. Account. Financ. Bus. Stud. 2018, 54, 547–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlon, M.; Selmrod, J. What does tax aggressiveness signal? Evidence from stock price reaction to News about tax shelter involvement. J. Public Econ. 2009, 50, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.S.; Jung, J.H. The Reaction of the Stock Market according to Tax Avoidance. Korean J. Tax. Res. 2008, 25, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, K.; Blouin, J.; Guay, W. Does Tax Aggressiveness Reduce Financial Reporting Transparency? Working Paper; University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, H.M.; Kang, G.I.; Lee, S.H.; Yoo, Y.K. Corporate tax avoidance and cost of equity capital: International evidence. Appl. Econ. 2020, 52, 3123–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R.; Davis-Nozemack, K. Tax Avoidance as a Sustainability Program. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 1009–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.A.; Dharmapala, D. Corporate tax avoidance and high powered incentives. J. Financ. Econ. 2006, 79, 145–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bankman, J. The tax shelter problem. Natl. Tax J. 2004, 57, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloyd, B.; Mills, L.; Weaver, C. Firm valuation effects of the expatriation of U.S. corporations to tax—Haven Countries. J. Am. Tax. Assoc. 2003, 25, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H.; Floyd, E.; Liu, L.; Maffett, M. The Real Effects of Mandatory Non-Financial Disclosures in Financial Statements; Working Paper; University Of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Milington, A. Firm size, organizational visibility and corporate philanthropy: An empirical analysis. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2006, 15, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C. The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, A.; Guenther, D.; Krull, L.; Williams, B. Do socially responsible firms pay more taxes? Account. Rev. 2016, 91, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennox, C.; Lisowsky, P.; Pittman, J. Tax aggressiveness and accounting fraud. J. Account. Res. 2013, 51, 739–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.K.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, G.O. The effects of corporate social responsibility on the tax avoidance. Study Account. Tax. Audit. 2015, 57, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Korea National Tax Service. Available online: https://www.nts.go.kr/nts/cm/cntnts/cntntsView.do?mi=2372&cntntsId=7746 (accessed on 9 July 2021).

- Lichtenstein, D.R.; Drumwright, M.E.; Braig, B.M. The effect of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to corporate-supported nonprofits. J. Mark. 2004, 689, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, D.; Cording, M. A corporate social performance–corporate financial performance behavioral model for consumers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 540–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.; Serafeim, G.; Krzus, M. Market interest in non-financial information. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2011, 23, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.A.; Kim, Y.S. the effect of managerial ability on short-term or long-term firm performance in Chaebol. Manag. Inf. Syst. Rev. 2017, 36, 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, H.S.; Kim, K.S. The relation of tax avoidance to embezzlement and malpractice. Korean J. Tax. Res. 2018, 35, 237–285. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).