Abstract

This study aims to examine the influence of an organization’s missions on employees’ turnover intention in the rarely studied context of social enterprises. Data collected from 236 full-time employees working for social enterprises in South Korea indicated that the negative relationship between social mission and turnover intention was mediated by the meaning of work; this mediation effect was weaker when the economic mission was stronger. The study contributes to the literature on organizational psychology (i.e., meaning of work, turnover) in the context of a new, but increasingly prevalent, organizational form—social enterprises. It also provides practical advice for managers seeking to retain and empower employees and enhance the sustainability of their social enterprises.

1. Introduction

Social enterprises aim to create social benefit through profit-seeking businesses [1]. The typical social enterprise has a specific social mission to clarify the intended social impact on the targeted beneficiaries [2]. The identity of a social enterprise is usually hybrid, combining the dual identities of profit seeker and social problem solver [3]. This study investigates how this uniqueness makes a difference in empowering employees. An increasing number of studies have been published on the management, leadership, and ecological trends of social enterprises [4]. To our knowledge, however, not many studies have focused on the social enterprise as a workplace for individual employees.

Social enterprises are distinguished from traditional nonprofit and public organizations by their profitable business models, which are designed to support sustainability and compete in the general market while tackling social problems [5]. Although such complexity requires more skills and strategies from employees in social enterprises, management resources, such as training systems and compensation packages, lack competitiveness in the market [6]. A close investigation of employees’ missions and job outcomes in social enterprises, therefore, can contribute to human resource management under limited resources and respond to the growing interest in social impact business [7].

This study examines the relationship between the salient organizational characteristics in social enterprises and the turnover intention critical to social enterprises from a managerial perspective. We focus particularly on the fact that social enterprises have dual missions [6]. In other words, most social enterprises pursue both the economic mission of seeking profit and the social mission of making a positive social impact [8]. Although such duality enables social enterprises to attain sustainability, it is also known to create challenging situations regarding employee management [9]. Since the organizational goal’s ambiguity impedes the employees from engaging in the work, we suspect that this unique characteristic of social enterprises, the dual missions, has important influences on individual employees. Specifically, the tension arising from two conflicting missions can have a significant impact on employees’ psychological processes related to forming their turnover intention.

To support our argument further, we adopt the notion of the meaning of work. Particularly, we hypothesize that the meaning of work, as perceived by individuals, mediates the relationship between the employees’ mission and the turnover intention [10]. More importantly, the coexistence of two missions that could sometimes conflict attenuates the positive impact of the meaning of work. This relationship can be captured by the negative moderation of the economic mission on the positive impact of the social mission for the meaning of work. The findings of this study can contribute to an explanation as to why employees in social impact businesses possess a strong sense of meaning in relation to their work but struggle to maintain it.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Meaning of Work in Social Enterprises

The study of employees’ behavioral motivation has extended beyond self-interest and monetary rewards, especially in mission-driven industries [11]. Early studies of public service organizations, for example, noted the uniqueness of intrinsic motivation in employees and showed its predictive role in positive job outcomes [12]. These studies claimed that altruistic and prosocial motivation is based on higher needs for “meaningful work” and a need to find a way of “making an impact” on others and the world [13]. For those with a strong motivation to serve others, a career is not only a paycheck but it is also a chance to realize one’s value. Therefore, the key question to these employees is, “Why do you work?”

Assumptions regarding one’s reason and purpose for working have evolved in the field of positive psychology as well. Positive psychologists have investigated the fundamental and affirmative impact of work on people’s lives [14]. Organizational psychologists have operationalized such positive components of work as “meaningfulness” [10]. Meaningful work, or the “employees’ understandings of what they do at work as well as the significance of what they do” [10], considers the “work experienced as particularly significant and holding more positive meaning for individuals” [15]. Several studies have provided substantial evidence on the benefits of meaningful work for individuals. These benefits have been shown to be related to positive work outcomes, such as job satisfaction, commitment, engagement, intrinsic motivation, and lower withdrawal behavior tendencies [16,17,18,19,20,21]. The meaning of work is also related to one’s life satisfaction level in general, even outside of work [22].

One of the important roles of the meaning of work is to mediate employees’ external surroundings and attitudes or behaviors [23]. The meaning of work can be explained as a feeling of empowerment [24]. Empowerment refers to the perceived control that enables employees to have proactive and autonomous motivation to interpret the opportunities in the organizational mission, vision, and value as an opportunity to change individual attitudes or behavior. Such control, which is captured in the meaning of work, influences the relationship between the changes in the structural context of the organization and actual individual job outcomes, such as turnover [25]. Following this notion, we propose that the perceived meaning of work mediates the organizational context (e.g., duality of missions) and job outcomes in favor of the organization (e.g., low turnover intention).

2.2. Turnover Intention in Social Enterprises

As many of the social enterprises are new, their managers, with limited budgets to invest in wages [26], are in need of a method more efficient than financial motivation to retain talented employees. Suitable human resources for social enterprises that are competent and socially committed are scarce in the market [27], causing the HR managers in industries much pressure. Unfortunately, we do not know much about the mindsets of employees choosing to leave social enterprises.

The recent efforts of social enterprise researchers to clarify the predictors of talent retention correspond to the need to uncover the causes of employees’ turnover intention and provide better experiences at work. At the organizational level, the complexity of the missions that social enterprises pursue adds a uniqueness to the turnover research in this field [28,29,30]. For instance, Moses and Sharma [31] investigated the human resource strategies of 180 healthcare social enterprises in India to explore the success factor for employee acquisition and turnover. Interestingly, the HR strategy of focusing on the economic mission was effective for acquisition but not retention. However, the strategy of focusing on the social mission had an impact on retention, but not on acquisition. Qualitative research on indigenous art center workers in Australian social enterprises showed that financial and social factors together could retain employees [32]. These results indicate the compounding interaction of the organizational missions of social enterprises on employee turnover, but more research is required on this.

Individual attitudes toward structural factors were also reported to affect turnover intention by several studies in the field. For example, the extent to which employees felt a sense of control over their jobs and decision making in a public organization predicted low turnover intention [33]. Individuals’ cognitive appraisal (e.g., perception) of organizational identity, leadership, or autonomy had a significant influence on turnover intention. The social enterprise workers’ cognitive identification with the organization had a positive impact on retention [34], whereas the individual perception of transformational leadership had a negative relationship with turnover intention in nonprofit organizations [35]. Besides the interpretation of a single factor either at the organizational or individual level, the congruence between the perceived values also had an effect on turnover. Person–organization fit, for example, had an influence on turnover intention in the public sector [36].

However, only a limited number of studies have paid attention to the combined effect of organizational and individual factors on turnover intention. Besides the fact that a highly emphasized social mission attracts more prosocial individuals [37,38,39], not much is known about how an organization’s prosocial values are related to the actual job behaviors [40].

Therefore, the current study focuses on the process of personalizing the organizational mission, which has a significant impact on the employees’ turnover intentions in social enterprises [41,42]. Social enterprises’ employees become more engaged and committed when they perceive strong personal control and participatory rights in organizational matters [43,44]. Additionally, the organizational context conveys a significant impact on their withdrawal attitudes when employees detect opportunities to be a proactive and independent agent from that context [33,45]. Based on this, we assert that employees are more likely to remain in an organization when they can identify with the organizational mission. As people’s interpretation of the organizational value is reflected in their meaning of work [46,47], we hypothesize that the meaning of work will mediate the negative relationship between the social mission and the turnover intention.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The meaning of work mediates the negative relationship between social mission and turnover intention.

2.3. Hybridity of Social Enterprises

Other philanthropic organizations such as NGOs and charity foundations also claim to have a strong social mission. The mission of social enterprises, however, is more than “philanthropic.” They operate in the same way as for-profit firms do for sustainability. In other words, they seek both economic and social value simultaneously [48]. As profit seeking is instrumental to realizing a “social” mission, the daily business of each employee is under the influence of the organization’s “economic” mission [8]. This uniqueness is often called a “dual mission,” or a “hybrid mission” [2,49]. The economic mission refers to the goal of profit maximization at the utilitarian identity level (as opposed to the normative identity), the amount of attention paid to the economic goal (as opposed to the social goal), and the extent to which the organization values its benefit (as opposed to others’ benefits) [8].

Scholars call organizations with plural business forms and missions “hybrid organizations” [29]. The mechanism of social enterprises, which consists of combining nonprofit and commercial organizations, places them in the category of a hybrid organization [2,50]. This mechanism provides social enterprises with multiple missions: social change and commercial success [6]. For example, Grameen Bank is a microfinance company supporting underprivileged citizens in Bangladesh. The company offers loans to groups of intended beneficiaries from the deposits of general customers. This means that they have multiple key success factors, such as offering attractive financial services for general customers and enhancing the beneficial impact for beneficiary groups. As in the case of Grameen Bank, a successful social enterprise maximizes its contribution to society from the synergy of multiple missions and goals.

We considered the fact that a social enterprise is a hybrid organization with a dual mission that is mutually exclusive for employees [51]. Organizations experience managerial difficulty when they face multiple role requirements [52] and complicated social expectations [53,54]. For example, if two conflicting and strong ideologies coexist for a long time, employees would experience stress and confusion [55]. The dual mission of social enterprises also illustrates the situation where one type of organizational mission requires employees to be philanthropic while another asks them to be profit oriented.

Hybridity has been shown to be an important element of social enterprises, one that suggests both business sustainability and the possibility of solving social problems [30]. Hybridity is also said to be a critical roadblock to success in the long run [28]. Previous studies have highlighted the tension arising from the dual mission as a critical risk factor for social entrepreneurs [56], but very few studies have examined the influence of such characteristics on employee attitudes or behaviors [57,58]. As previous studies have been substantially constrained in conceptual and theoretical discussions (e.g., [29,57]), empirical evidence on the impact of hybridity corresponds to the recent calls for more studies on the potential difficulties of diverse parties in social enterprises.

2.4. Difficulties in Dual Missions

Hybridity can create tension in social enterprises [9] and can even lead to business failure [29]. Tension is inevitable for social enterprises because resolving their problems by removing either of the two missions can result in mission drift [59,60]. Several of the difficulties that arise from social enterprises’ dual mission are due to this tension.

Siegner et al. reviewed and summarized the claims of researchers on the results of tension in social enterprises [61]. First, conflicts arise from stakeholders pursuing different missions [28]. Details and time perspectives in relation to goals also conflict. Therefore, the daily tasks and relational activities of each goal are in conflict [43]. Frequent conflicts cause disagreements about missions, human resource management, and business output [30].

Even though the direct effect of dual missions on individual employees in social enterprises has not been examined, studies on role ambiguity and conflicts provide inferential ideas. Conflict, defined as “disagreements among group members over the content of their decisions and differences in viewpoints, ideas, and opinions related to the task,” is similar to the problem caused by mission duality in that it causes tension within the group [62]. In particular, task conflict, or “conflicts about the distribution of resources, procedures and policies, and judgments and interpretation of facts” [63] is known to produce emotional tension and antagonism, and distracts team members [64]. It also undermines the employees’ job satisfaction and productivity [65]. Ambiguity, another possible consequence of dual missions, refers to the employees’ perception of uncertainty about various job aspects [66]. If employees feel that any aspect of the current job is unclear (e.g., expected role, opportunity, task impact), they would be frustrated and anxious, and avoid proactive behavior [67]. The job performance level [68] and extra-role behavior also decrease [69].

From similar concepts in previous studies, this study tries to find empirical evidence for psychological pressure from the social enterprises’ duality of mission. Specifically, the combination of social and economic missions is the target of concern [8].

2.5. Moderating Role of Economic Mission

Stevens and colleagues defined the goal of social enterprises as the pursuit of profits, as opposed to the social mission as an “economic mission” [8]. Their empirical research found that the social mission and the economic mission are negatively related. This finding aligns with the conventional assumption that attention given to one mission inhibits the other. With regard to scarce resources in social enterprises, one can argue that a strong social mission can suppress investment in the economic mission, or vice versa [70]. Discussions on the tension in social enterprises heavily depend on this view and focus on the managerial perspective of splitting the available resources [6,8]. This approach, however, does not assume a situation where both social and economic missions are strong [8]. Researchers have called for further discussion and studies on such limitations [71].

Considering the past findings and calls for research, we attempt to investigate whether having high levels of both missions affects employees. The pressure of pursuing both social and economic missions can hinder employees from finding their work meaningful. An organizational mission presents the standard for employees’ behavior and decision making [72] and influences the meaning of work in previous studies [40]. Strong but conflicting missions, therefore, present multiple standards for aligning activities toward the mission. Decisions and behavior are likely to be censored repeatedly under these standards. Repeated censorship on activities is likely to deter autonomy and eventually lower the meaning of work [73,74]. Moreover, finding congruence between organizational and personal missions when there is no absolute priority would be more difficult [47,75]. Therefore, pursuing strong social and economic missions simultaneously would prevent employees from finding significant meaning in their work.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The economic mission moderates the relationship between the social mission and work meaningfulness such that the relationship becomes weaker when the economic mission is stronger.

We can find such influences in the form of moderated mediation as well. In other words, the pressure of a dual mission can interfere with the conversion of the social mission into a positive job attitude through work meaningfulness.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The economic mission moderates the mediation of work meaningfulness in the negative relationship between the social mission and the turnover intention such that the mediation effect is weaker when economic mission is stronger.

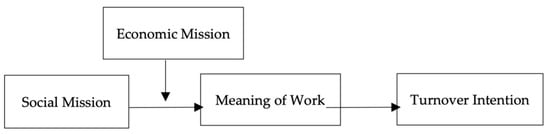

The relationships proposed in this study are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The proposed research model.

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedure

Data were collected from full-time employees working for social enterprises in Seoul, Korea. We recruited voluntary participants from members in shared offices where only social impact-related companies operate. The shared office only accepts the companies which have a clear social mission as tenants. These companies include social impact investors, consumer product manufacturers and distributors, IT solution providers, and consulting firms. The announcement was posted on physical boards with a brief explanation about the study and the qualification for participation. A total of 388 employees from five shared office buildings participated in the survey. One hundred and fifty-two cases with missing information and invalid answers were deleted listwise, resulting in a final sample of 236 respondents. The sample consisted of 136 women (57.6%) and 85 men (36.0%), with the rest unknown. The average age of participants was 33.2 years (SD = 9.16), the average organizational tenure was 2.69 years (SD = 2.71), and the average time in years after high school education was 4.01 (SD = 1.47).

3.2. Measures

We developed a Korean version of the questionnaire using the forward-and-backward translation method with the assistance of three Korean–English bilinguals [76], except for the meaning of work which had already been validated into Korean [77]. All items except the demographic variables were measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Meaning of work: The meaning of work was measured using 10 items from the Korean version of the Work and Meaning Inventory [21,77]. Examples of the questionnaire include “The work I do serves a greater purpose,” and “I have found a meaningful career.” The scale yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95.

Economic and Social mission: We measured the employees’ perceptions of their organization’s mission using three items adapted from Aupperle et al. and Stevens et al. [8,78]. A sample item for the economic mission includes “It is important to our organization that long-term return on investment is maximized” and for the social mission, “It is important to our organization that we have the opportunity to participate in activities that address social issues.” The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale of the social mission was 0.81 and 0.88 for the economic mission.

Turnover intention: We assessed the turnover intention using three items from the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire [79]. A sample item is, “I often think about quitting my job”; the scale yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89.

Control variables: We assessed the following values for the purpose of control variables in our analysis: gender (male = 1, female = 0); age (years), education (years after high school); marital status (married = 1, not married = 0); organizational tenure (years); overtime work (hours); and job type (technical job = 1; nontechnical job = 0).

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model and Common Method Variance Check

We first tested the measurement model which consisted of four factors: social mission, economic mission, meaning of work, and turnover intention. After parceling 10 items measuring the meaning of work to three constructs and allowing an additional correlated residual among the items within turnover intention based on modification indices [21], the chi-square statistic was found to be significant: X2 (47, N = 236) = 102.32, p < 0.001. The other fit indices were at an acceptable level (CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.07). All items were loaded to their latent variable (p < 0.001), with the standardized factor loading between 0.67 and 1.03. An alternative measurement model in which social mission, economic mission, meaning of work, and turnover intention were fixed to a single latent variable did not show a better fit to the data (X2 (53, N = 236) = 849.49, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.56, RMSEA = 0.25).

We also tested alternative measurement models in which items from social mission, economic mission, or meaningful work were fixed as indicators of a single latent variable. These alternative models showed a worse fit to the data than the hypothesized measurement model (social mission and meaning of work combined: X2 (50, N = 236) = 265.61, p < 0.000, CFI = 0.88, RMSEA = 0.14; social mission and economic mission combined: X2 (50, N = 236) = 430.05, p < 0.000, CFI = 0.79, RMSEA = 0.18; economic mission and meaningful work combined: X2 (50, N = 236) = 505.19, p < 0.000, CFI = 0.57, RMSEA = 0.20).

Finally, an additional confirmatory factor analysis with a common latent factor linked to all the measured items was implemented [80]. The model with the common method factor showed a worse fit (X2 (49, N = 236) = 117.48, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.08) than the four-factor model, but with no dramatic improvement in indices. Therefore, we ruled out the compounding of common method variance.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations for the observed variables. We tested the hypothesis using the PROCESS macros developed by Hayes [81].

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations.

The social mission had an indirect effect on turnover intention via the meaning of work (indirect effect = −0.32, SE = 0.08, 95% CI [−0.49 to −0.18]). The direct effect was also found to be significant (direct effect = −0.33, SE = 0.10, 95% CI [−0.54, −0.13]). The results showed that the negative relationship between the social mission and the turnover intention is mediated by the meaning of work, supporting Hypothesis 1.

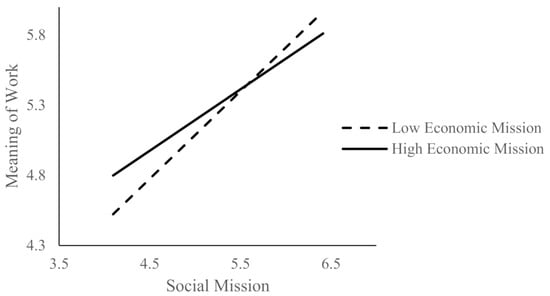

Next, we tested the moderation effect on economic mission. As predicted, the economic mission moderated the relationship between the social mission and the meaning of work (b = −0.07, p < 0.05). Figure 2 shows that the positive relationship between the social mission and the meaning of work becomes stronger when the economic mission is lower (−1SD) and weaker when the economic mission is higher (+1SD). This result supports Hypothesis 2.

Figure 2.

The interaction of the social mission and the economic mission predicting the meaning of work.

Then we checked whether the mediated effect of the meaning of work was moderated by the economic mission. A bootstrap analysis was conducted to examine the indirect effect of the social mission on the turnover intention with the moderation of the economic mission (Table 2). The index of the moderated mediation was significant (b = 0.04, SE = 0.02, CI = [0.00, 0.08]), implying that the negative indirect effect between the social mission and the turnover intention was stronger when the economic mission was one standard deviation below the mean (conditional indirect effect = −0.38, SE = 0.09, CI = [−0.56, −0.22]) and weaker when it was one standard deviation above the mean (conditional indirect effect = −0.28, SE = 0.08, CI = [−0.45, −0.14]). Thus, Hypothesis 3 is also supported.

Table 2.

Bootstrap analysis of the conditional indirect effects of the meaning of work.

5. Discussion

The results of this study indicate the possibility that conflicting social and economic missions suppress the positive influence of the organizational context in social enterprises. When the level of the perceived economic mission was high, the positive relationship between the social mission and the meaning of work, and the indirect effect of the social mission on the turnover intention weakened. Dual missions, compared to single missions, are not sufficiently associated with the personal level to affect one’s behavior, thereby causing an individual to leave the job. In other words, the organizational mission along with the economic mission prompts individuals to perceive less personal meaning in their job and thwarts the turnover intention. These results support the previous claim that a clear mission can be easily communicated by providing the employees with a clear goal [82]. Although the coexistence of multiple missions is essential for sustaining the social impact of an organization [83], its influence on an individual’s motivational attitudes needs further research.

Social and economic missions demand different behavioral and success standards. An economic mission requires more visible and immediate outcomes, whereas a social mission prioritizes long-term benefits and returns. Such discrepancies can jeopardize the ability of employees to find consistencies in the respective rules and standards of the two missions. An evaluation for proper work behavior and performance may fluctuate, as a certain achievement may suit the social mission but violate the economic mission. Such dissonance delays decision making and undermines achievement, making it difficult to maintain a solid and viable meaning of work when the significance of a job is repeatedly questioned and underestimated [84]. This interpretation supports the literature, suggesting that the impact of the meaning of work depends on the extent to which employees can easily understand the purpose and consequence of the given tasks [84].

Especially for employees who strongly intend to contribute to the community by aligning with the social mission of social enterprises [38], a strong social mission is a critical source for interpreting the purpose of work and finding congruence between self and organization [23,47]. The economic mission, which promotes less internal motivation for social enterprise employees than the social mission does, seems to mitigate the power of the social mission to find the meaning of work and the intention to stay in the organization [85].

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The current study empirically characterized the context of social enterprises with dual organizational missions. The explicit investigation of the most salient aspect of social enterprises, or dual missions, enhances our understanding of the motivational ties between two agents, the organization and individual, who share a similar prosocial purpose. Setting clear priorities for each of the conflicting missions contributes to the positive influence of the social enterprises’ inherent good nature on the employees’ meaning of work and withdrawal intentions.

Another significant contribution lies in testing the enabling role of the meaning of work in the context of social enterprises. Although the meaning of work is essentially a psychological factor related to a career concerning social impact, social enterprises have rarely been studied from this perspective [86]. The social mission, which is central to the identity of social enterprises, does not seem to serve as a sufficiently powerful motivator without the corresponding meaning of work [87]. Social entrepreneurship researchers have suggested that the social mission is a critical construct for those devoting their career to the social sector, but the presence of personal meaning seems to be essential for that construct to have a motivational effect for employees.

The present study also contributes to the literature by broadening the organizational conditions to constrain unfavorable attitudes in the context of social enterprises (e.g., turnover intention). Turnover scholars have called for the need to clarify the conditional factors that make certain antecedents more or less powerful to predict withdrawals [88]. In the previous study by Sun and colleagues, the effect of the social mission on turnover intention via the meaning of work was positively moderated to the extent of a clear perception of the organizational vision [40]. In other words, the meaning of work translated the social mission into a lower turnover intention well when the vision was communicated well. The current study also substantiates the previous finding by showing that a clearly weighted social mission not blurred by the economic mission predicts a lower turnover than the social mission combined with a conflicting economic mission.

5.2. Practical Implications

The results also yield practical implications for the social enterprise sector. Managers in social enterprises have to pay special attention to offering clear-cut priorities for a dual mission. The tension arising between economic and social missions confuses employees in the performance of their daily tasks and interferes with their meaning of work in the long run. Clarifying the company’s core values and code of conduct can reduce employee stress by relieving the burden of decision making and lessening the task conflicts within teams [89,90].

Researchers and practitioners have attempted to determine how to motivate and retain talented employees under complicated circumstances (e.g., a company’s dual missions) with limited resources. The complicated demand of fulfilling both social and economic missions essentially affects both individuals and entrepreneurs [61]. Although the experimental data show that the monetary incentive structure is effective [91], not many social enterprises pay competitive wages [92]. Moreover, little is known about the motivating strategies underlying the challenges related to dual missions, and individuals who face challenges related to social enterprise businesses have been largely neglected by the academic community [9]. However, the current study is meaningful as it provides a model accounting for the specific nature of social enterprises [93]. Understanding how the meaning of work is affected by the work context (e.g., a dual mission) can contribute to the motivation of employees and can help them develop a scheme appropriate for the social sector. Therefore, managers should investigate whether their current organizational mission stimulates employees’ personal meaning of work. The organizational mission can appeal to diverse parties, such as stakeholders, customers, and employees [94]. It is important for the managers to check whether the employees find enough meaning of work from the organizational mission. More importantly, it is critical for them to verify whether either the economic or social mission is impeding the other and preventing employees from being engaged in the mission.

Social enterprises constitute only a limited portion of the entire global industry. However, studying the challenges and managerial issues in this sector still has significance given its potential for growth. Although social enterprises started as an alternative response to government and market failure, the forecast regarding their growth is promising [95]. Since both society’s transformation and problems are growing at an unexpected pace, traditional authorities do not seem to have solutions; thus, hybrid forms of organizations are increasingly expected to provide answers. Moreover, the market has started to punish immorality (e.g., the Johnson & Johnson lawsuit), while organizational integrity has drawn more attention and consumer commitment [96]. Therefore, more for-profit organizations are likely to be required to have social missions as part of their identities. This study’s findings enhance the understanding of the work context and outcomes in an industry that has tremendous social responsibility.

5.3. Limitation and Direction for Future Research

Our study has some limitations. Besides the limitation of cross-sectional data, the proposed model structure does not perfectly capture all the possible cases of inherent tension in social enterprises. First, we did not directly measure the tension level, but assumed that two discrete missions would be followed by tension and the effect would be illustrated by interactions. Although the moderation effect in the current study implies the hindering role of tension, it does not directly indicate the perceived level of tension. Moreover, the negative moderation effect in the current research illustrates the negative effect of tension only when both the economic and social missions are strong. In other words, a stronger social mission has less impact on employees when the economic mission is also strong. However, tension can occur when both the social mission and economic mission match at an average level, even though this is not a typical situation. Future research should use more explicit methods of assessing the tension due to dual missions. For example, researchers could directly ask about the perceived stress and confusion that can arise due to conflicting dual missions.

Self-reported turnover intention is another limitation of the current study. Although turnover intention is a significant predictor of actual turnover, the possibility of it not fully reflecting the actual turnover ratio still exists [97]. Furthermore, we investigated only one type of withdrawal behavior: voluntary turnover intention. We chose to do so because it is one of the most critical work outcomes affecting a social enterprise’s business success. As the current research confirmed the limited role voluntary turnover intention plays among multiple layers in social enterprises and employees’ withdrawal intentions, further investigation of diverse work outcomes—such as actual turnover or emotional status—is essential.

Additionally, future research could expand the scope of the subject beyond that of organizational psychology to include socio-economic and legislative perspectives. For example, a chain of stakeholders who are influenced by high employee turnover in social enterprises could be investigated [94]. Since social enterprises fall under a unique legal framework, it is also recommended that legislators’ responsibility in supporting social enterprises to retain their employees is explored [98].

6. Conclusions

This study began with a simple question regarding whether the complexity of social enterprises is a burden on employees and leaders [61]. The empirical evidence demonstrates the role of the meaning of work in delivering social enterprises’ social and economic missions to the employees to help them form a certain degree of turnover intention. The moderating effect found in our study demonstrates the possibility that the tension between the social and economic missions causes a low meaning of work and a high turnover intention.

Although the study has limitations, such as the implicit way of measuring the conflicts between missions and turnover behavior, we believe our efforts add to the ongoing academic research related to the demonstration of the socio-structural elements and personal job outcomes in social enterprises. Future research will make more significant contributions by investigating the intricate relationship between social and economic missions and clarifying the outcomes when two missions compete with each other. We hope our study contributes not only to social enterprises but also to mission-pursuing organizations, which are interested in making talented individuals with goodwill remain in the business.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, J.S.; review and editing, Y.W.S. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University (IRB No. 7001988-202001-HR-617-05).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy issues.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Germak, A.J.; Robinson, J.A. Exploring the Motivation of Nascent Social Entrepreneurs. J. Soc. Entrep. 2014, 5, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacin, P.A.; Dacin, M.T.; Matear, M. Social Entrepreneurship : Why We Don’t Need a New Theory and How We Move Forward from Heer. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2010, 8, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.; Gillett, A.; Doherty, B. Sustainability in Social Enterprise: Hybrid Organizing in Public Services. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, P.; Wach, D.; Wegge, J. What Motivates Social Entrepreneurs? A Meta-Analysis on Predictors of the Intention to Found a Social Enterprise. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 59, 477–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, G.; Anderson, B. For-Profit Social Ventures. Int. J. Entrep. Educ. 2003, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.; Stevenson, H.; Wei–Skillern, J. Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letaifa, S.B. How Social Entrepreneurship Emerges, Develops and Internationalises during Political and Economic Transitions. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2016, 10, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, R.; Moray, N.; Bruneel, J. The Social and Economic Mission of Social Enterprises: Dimensions, Measurement, Validation, and Relation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 1051–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Gonin, M.; Besharov, M.L. Managing Social-Business Tensions: A Review and Research Agenda for Social Enterprise. Bus. Ethics Q. 2013, 23, 407–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E.; Debebe, G. Interpersonal Sensemaking and the Meaning of Work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2003, 25, 93–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassar, L.; Meier, S. Nonmonetary Incentives and the Implications of Work as a Source of Meaning. J. Econ. Perspect. 2018, 32, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.L.; Wise, L.R. The Motivational Bases of Public Service. Public Adm. Rev. 1990, 50, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, C.; Neumann, O.; Baertschi, M.; Ritz, A. Public Service Motivation, Prosocial Motivation and Altruism: Towards Disentanglement and Conceptual Clarity. Int. J. Public Adm. 2019, 42, 1200–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.S.; Caza, A. Introduction: Contributions to the Discipline of Positive Organizational Scholarship. Am. Behav. Sci. 2004, 47, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, K.A.; Turner, N.; Barling, J.; Kelloway, E.K.; McKee, M.C. Transformational Leadership and Psychological Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Meaningful Work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, R.D.; Autin, K.L.; Bott, E.M. Work Volition and Job Satisfaction: Examining the Role of Work Meaning and Person–Environment Fit. Career Dev. Q. 2015, 63, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Douglass, R.P.; Autin, K.L. Career Adaptability and Academic Satisfaction: Examining Work Volition and Self Efficacy as Mediators. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 90, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.S.; Yoon, H.H. What Does Work Meaning to Hospitality Employees? The Effects of Meaningful Work on Employees’ Organizational Commitment: The Mediating Role of Job Engagement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littman-Ovadia, H.; Steger, M. Character Strengths and Well-Being among Volunteers and Employees: Toward an Integrative Model. J. Posit. Psychol. 2010, 5, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, F.; Stander, M.W. Positive Organisation: The Role of Leader Behaviour in Work Engagement and Retention. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2011, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Steger, M.F.; Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D. Measuring Meaningful Work: The Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI). J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, B.A.; Batz-Barbarich, C.; Sterling, H.M.; Tay, L. Outcomes of Meaningful Work: A Meta-Analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 56, 500–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the Meaning of Work: A Theoretical Integration and Review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. An Empirical Test of a Comprehensive Model of Intrapersonal Empowerment in the Workplace. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 601–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suifan, T.S.; Diab, H.; Alhyari, S.; Sweis, R.J. Does Ethical Leadership Reduce Turnover Intention? The Mediating Effects of Psychological Empowerment and Organizational Identification. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2020, 30, 410–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, A.; Barraket, J. Engaging Workers in Resource-Poor Environments: The Case of Social Enterprise in Vietnam. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 2949–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohana, M.; Meyer, M. Should I Stay or Should I Go Now? Investigating the Intention to Quit of the Permanent Staff in Social Enterprises. Eur. Manag. J. 2010, 28, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, A.; Battilana, J.; Mair, J. The Governance of Social Enterprises: Mission Drift and Accountability Challenges in Hybrid Organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 2014, 34, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Lee, M. Advancing Research on Hybrid Organizing–Insights from the Study of Social Enterprises. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 397–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, B.; Haugh, H.; Lyon, F. Social Enterprises as Hybrid Organizations: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, A.; Sharma, A. What Drives Human Resource Acquisition and Retention in Social Enterprises? An Empirical Investigation in the Healthcare Industry in an Emerging Market. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 107, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seet, P.S.; Jones, J.; Acker, T.; Jogulu, U. Meaningful Careers in Social Enterprises in Remote Australia: Employment Decisions among Australian Indigenous Art Centre Workers. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 1643–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Fernandez, S. Employee Empowerment and Turnover Intention in the U.S. Federal Bureaucracy. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2015, 47, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rho, E.; Yun, T.; Lee, K. Does Organizational Image Matter? Image, Identification, and Employee Behaviors in Public and Nonprofit Organizations. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T. Relationship between Transformational Leadership in Social Work Organizations and Social Worker Turnover. Am. J. Sociol. Res. 2016, 6, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Hu, J. Person-Organization Fit, Job Satisfaction, and Turnover Intention: An Empirical Study in the Chinese Public Sector. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2010, 38, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.K.; Stazyk, E.C. Antecedents and Correlates of Public Service Motivation. In Motivation in Public Management: The Call of Public Service; Hondeghem, A., Perry, J.L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 101–117. ISBN 978-0-19-155283-0. [Google Scholar]

- Caringal-Go, J.F.; Hechanova, M.R.M. Motivational Needs and Intent to Stay of Social Enterprise Workers. J. Soc. Entrep. 2018, 9, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. Behavioral Implications of Public Service Motivation. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2012, 42, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Lee, J.W.; Sohn, Y.W. Work Context and Turnover Intention in Social Enterprises: The Mediating Role of Meaning of Work. J. Manag. Psychol. 2019, 34, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J.; Lewis, G.B. Turnover Intention and Turnover Behavior: Implications for Retaining Federal Employees. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2012, 32, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Fried, Y.; Juillerat, T. Work Matters: Job Design in Classic and Contemporary Perspectives. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Vol 1: Building and Developing the Organization; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 417–453. ISBN 1-4338-0732-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.W.; Zhang, L.; Dallas, M.; Chin, H. Managing Relational Conflict in Korean Social Enterprises: The Role of Participatory HRM Practices, Diversity Climate, and Perceived Social Impact. Bus. Ethics 2019, 28, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Dallas, M.; Xu, S.; Hu, J. How Perceived Empowerment HR Practices Influence Work Engagement in Social Enterprises–a Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 2971–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. Psychological Empowerment to the Organizational Commitment and Turnover Intention of Social Worker. Int. J. Contents 2012, 8, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besharov, M.L. Mission Goes Corporate: Employee Behavior in a Mission-Driven Business. Ph.D. Thesis, Harvard University, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.; Bunderson, S. Violations of Principle: Ideological Currency in the Psychological Contract. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Martí, I. Social Entrepreneurship Research: A Source of Explanation, Prediction, and Delight. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.L.; Wesley, C.L. Assessing Mission and Resources for Social Change: An Organizational Identity Perspective on Social Venture Capitalists’ Decision Criteria. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 705–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, P.; Brescia, V.; Fantauzzi, C.; Frondizi, R. Understanding Social Impact and Value Creation in Hybrid Organizations: The Case of Italian Civil Service. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman, P.; Whetten, D.A. Members’ Identification with Multiple-Identity Organizations. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 618–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N.A.; Khazon, S.; Alarcon, G.M.; Blackmore, C.E.; Bragg, C.B.; Hoepf, M.R.; Barelka, A.; Kennedy, K.; Wang, Q.; Li, H. Building Better Measures of Role Ambiguity and Role Conflict: The Validation of New Role Stressor Scales. Work Stress 2017, 31, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraatz, M.S.; Block, E.S. Organizational Implications of Institutional Pluralism. In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism; Greenwood, R., Oliver, C., Lawrence, T.B., Meyer, R.E., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2017; pp. 243–275. ISBN 978-1-5264-1505-9. [Google Scholar]

- Pache, A.; Santos, F. When Worlds Collide: The Internal Bynamics of Organizational Responses to Conflicting Institutional Demands. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whetten, D.; Foreman, P.; Dyer, W.G. Organizational Identity and Family Business. Sage Handb. Fam. Bus. 2014, 480–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargsted, M.; Picon, M.; Salazar, A.; Rojas, Y. Psychosocial Characterization of Social Entrepreneurs: A Comparative Study. J. Soc. Entrep. 2013, 4, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.; Doherty, B. A Fair Trade-off? Paradoxes in the Governance of Fair-Trade Social Enterprises. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sandt, C.V.; Sud, M.; Marmé, C. Enabling the Original Intent: Catalysts for Social Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 90, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, C.; Cornforth, C. Understanding and Combating Mission Drift in Social Enterprises. Soc. Enterp. J. 2014, 10, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, T.; Vaccaro, A. Stakeholders Matter: How Social Enterprises Address Mission Drift. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegner, M.; Pinkse, J.; Panwar, R. Managing Tensions in a Social Enterprise: The Complex Balancing Act to Deliver a Multi-Faceted but Coherent Social Mission. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1314–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehn, K.A. A Multimethod Examination of the Benefits and Detriments of Intragroup Conflict. Adm. Sci. Q. 1995, 40, 256–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C.K.W.; Weingart, L.R. Task versus Relationship Conflict, Team Performance, and Team Member Satisfaction: A Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, N.; Chen, Z.; Gu, J.; Huang, S.; Liu, H. Conflict and Creativity in Inter-Organizational Teams. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2017, 28, 74–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Zhou, E.; Gao, P.; Long, L.; Xiong, J. Double-Edged Effects of Socially Responsible Human Resource Management on Employee Task Performance and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Mediating by Role Ambiguity and Moderating by Prosocial Motivation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breaugh, J.A.; Colihan, J.P. Measuring Facets of Job Ambiguity: Construct Validity Evidence. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Rothbard, N.P. When in Doubt, Seize the Day? Security Values, Prosocial Values, and Proactivity under Ambiguity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilboa, S.; Shirom, A.; Fried, Y.; Cooper, C. A Meta-Analysis of Work Demand Stressors and Job Performance: Examining Main and Moderating Effects. Pers. Psychol. 2008, 61, 227–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Paine, J.B.; Bachrach, D.G. Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Critical Review of the Theoretical and Empirical Literature and Suggestions for Future Research. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 513–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, B.; Miller, K.; McAdam, R.; Moffett, S. Mission or Margin? Using Dynamic Capabilities to Manage Tensions in Social Purpose Organisations’ Business Model Innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, N.A.; Giovacchini, E. The Best of Both Worlds: Strategy Formation in a Company with Hybrid Identities. Proceedings 2020, 2020, 14015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dick, R.; Crawshaw, J.R.; Karpf, S.; Schuh, S.C.; Zhang, X. Identity, Importance, and Their Roles in How Corporate Social Responsibility Affects Workplace Attitudes and Behavior. J. Bus. Psychol. 2020, 35, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, Y.; Ferris, G. The Validity of the Job Characteristics Model: A Review and Meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol. 1987, 40, 287–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, R.; Lawler, E. Employee Reactions to Job Characteristics. J. Appl. Psychol. 1971, 55, 259–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.G. The Good, the Bad, and the Ambivalent: Managing Identification among Amway Distributors. Adm. Sci. Q. 2000, 45, 456–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. The wording and Translation of Research Instruments. In Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research, Cross-Cultural Research and Methodology Series; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1986; Volume 8, pp. 137–164. ISBN 0-8039-2549-2. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Lee, J. Validation of Korean Version of Working As Meaning Inventory. Korean J. Soc. Pers. Psychol. 2017, 31, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupperle, K.E.; Carroll, A.B.; Hatfield, J.D. An Empirical Examination of the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1985, 28, 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammann, C.; Fichman, M.; Jenkins, D.; Klesh, J. The Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1979; Available online: https://www.scirp.org/(S(i43dyn45teexjx455qlt3d2q))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=2018239 (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Widaman, K.F. Hierarchically Nested Covariance Structure Models for Multitrait-Multimethod Data. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1985, 9, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 1-4625-3465-1. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, W.A.; Yoshioka, C.F. Mission Attachment and Satisfaction as Factors in Employee Retention. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2003, 14, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, T.W.; Short, J.C.; Payne, G.T.; Lumpkin, G.T. Dual Identities in Social Ventures: An Exploratory Study. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 805–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, B.A.; Duffy, R.D.; Collisson, B. Task Significance and Performance: Meaningfulness as a Mediator. J. Career Assess. 2018, 26, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbano, V.C. Social Responsibility Messages and Worker Wage Requirements: Field Experimental Evidence from Online Labor Marketplaces. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 1010–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.M.C.; Au, W.C.; Leung, V.T.Y.; Peng, K.L. Exploring the Meaning of Work within the Sharing Economy: A Case of Food-Delivery Workers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraher, S. Social Entrepreneurship: Interviews, Journal Surveys, and Measures. J. Manag. Hist. 2012, 18, 364–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, P.W.; Lee, T.W.; Shaw, J.D.; Hausknecht, J.P. One Hundred Years of Employee Turnover Theory and Research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaton, E.E.; Dowin Kennedy, E. Responding to Failure: The Promise of Market Mending for Social Enterprise. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 641–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Slaten, T.; Choi, W.J. Felt Betrayed or Resisted? The Impact of Pre-Crisis Corporate Social Responsibility Reputation on Post-Crisis Consumer Reactions and Retaliatory Behavioral Intentions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C.K.W.; van Dierendonck, D.; Dijkstra, M.T.M. Conflict at Work and Individual Well-being. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2004, 15, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin, P.M. Corporate Codes of Conduct: The Effects of Code Content and Quality on Ethical Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 99, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condly, S.J.; Clark, R.E.; Stolovitch, H.D. The Effects of Incentives on Workplace Performance: A Meta-analytic Review of Research Studies. Perform. Improv. Q. 2003, 16, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Huh, S.; Cho, S.; Auh, E.Y. Turnover and Retention in Nonprofit Employment. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2015, 44, 641–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzaga, C.; Solari, L. Management Challenges for Social Enterprises. In The Emergence of Social Enterprise; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; pp. 333–349. ISBN 1134526725. [Google Scholar]

- Streimikiene, D.; Lasickaite, K.; Skare, M.; Kyriakopoulos, G.; Dapkus, R.; Duc, P.A. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Corporate Image: Evidence of Budget Airlines in Europe. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Wang, W. Transformational Leadership, Employee Turnover Intention, and Actual Voluntary Turnover in Public Organizations. Public Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 1124–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulos, G.L. Environmental Legislation in European and International Contexts: Legal Practices and Social Planning toward the Circular Economy. Laws 2021, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).