1. Introduction

Decentralised renewable energy technologies, such as solar home systems (SHSs), are increasingly being used to provide electricity in South Asia. Scholars, policymakers, and practitioners contend that SHSs have a vital role to play in meeting the UN’s Sustainable Goal 7 (SDG7), i.e., establishing affordable, reliable, and modern energy services for all by 2030. In Bangladesh, which is at the forefront of SHS adoption in South Asia, about 20 million people have access to electricity through this technology [

1], while according to estimates, the SHS market in India will increase from 18% in 2018 to 42% by 2023 [

2]. In Nepal, over 900,000 households have access to energy via stand-alone photovoltaic (PV) systems [

3]. In Sri Lanka, during the Energy Services Delivery project, which ran from 1997 to 2002, and the Renewable Energy for Rural Economic Development project, which ran from 2002 to 2011, a total of 131,528 SHSs were purchased by rural residents [

4]. In Pakistan, the Sindh Solar Energy Project recently allocated US

$30 million to provide 200,000 rural households with access to SHSs [

5].

The purpose of this study is threefold: (a) to examine how categories of difference such as age, gender, ethnicity, and class influence the adoption of SHSs in South Asia; (b) to explore how energy generated by this technology is used in households; (c) to examine how the uptake of this technology reconfigures daily routines and practices. A systematic methodology review was used in this study in order to meet the purpose of this research. Despite the importance of this renewable energy technology, a systematic review has not yet been conducted to examine how different categories of difference shape its uptake in South Asia, including how its adoption (re)shapes everyday routines in the region. This omission is problematic because SHSs are currently an integral part of the energy landscape in South Asia and will continue to play a significant role in the provision of energy in the region. Therefore, as these products will continue to play an important role in the provision of electricity in the region, it is important to understand energy consumption behaviours as well as the social practices related to their use. Additionally, the study is important because it highlights the benefits of SHSs and provides evidence for policy interventions aimed at improving the performance of these products. It focuses on South Asia, as this region was one of the earliest adopters of SHSs and is one of the leading and fastest growing SHS markets. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first paper that examines these issues in South Asia and is specifically based on a systematic review of academic literature.

This paper makes three key contributions. First, it contributes to the literature on social differentiation and renewable energy technologies by showing how the adoption of SHSs is not solely driven by economic factors. Rather, diverse categories of difference such as gender, age, class, and ethnicity also shape the likelihood of people adopting these systems, and influence how solar energy is used in households in South Asia. Second, the social practice theory framework is used to analyse how SHSs shape the spatial and temporal practices of adopters. The paper also contributes to the debate around renewable energy technologies and social practices by showing how the adoption of this technology by some households equally influences the spatial and temporal practices of non-SHS adopters in the community. Third, based on the economic and socio-cultural contexts, the adoption of this renewable energy technology has both a practical and symbolic function. In doing so, this study shows that SHSs are not just technologies for expanding access to electricity, but also facilitate the (re)production of social worth in local communities.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 introduces social practice theory and intersectionality framework in the context of SHSs, while

Section 3 outlines the methodological approach used for this review.

Section 4 presents the study’s findings, and

Section 5 discusses the results and limitations of the review, identifying future research opportunities. The final section provides concluding remarks and makes some recommendations in terms of policy and programme design.

2. SHSs through Social Practice Theory and Intersectionality Lenses

Energy consumption studies are increasingly investigating everyday practices as they relate to energy consumption from a practice theory approach [

6], which indicates an understanding of people’s energy consumption being closely related to routinised practices [

7]. Practice theory bridges the dualism between agency and structure and particularly draws on the work of Pierre Bourdieu and Anthony Giddens. Bourdieu [

8] highlighted the habitual dimensions of agency and the manner in which it is intimately linked to past life experience, and his concept of habitus builds on the notion that people act purposively and practically rather than blindly following formal norms [

9]. Bourdieu argued that actors respond to past experience and noted that habits are not just constituted by past experience of socialisation but are also constitutive of ongoing practices [

10]. This perspective aligns with Giddens’s [

11] notion of routinised practical consciousness. Giddens [

11] made a compelling point that the focus of social science research should be based on “neither the experience of the individual actor, nor the existence of any form of social totality, but social practices ordered across space and time”. People do not simply engage in routinised behaviours, but rather they possess the ability to imagine possibilities [

12]. In other words, people live by adjusting the diverse temporalities of their existence and by drawing on various experiences to develop new ways of doing things [

12]. Clearly, social practice theory seeks to understand the complex relationship between agency, structure, and context in diverse social phenomena, hence capturing the richness of people’s behaviour and locating this within a local environment [

13].

More recently, scholars have applied social practice theory to the study of energy consumption and energy behaviour in the Global South [

6,

14]. Practices are viewed as routinised forms of behaviour [

15], and the material dimension linked to them is central to energy consumption research. Shove et al. [

16] framed ‘practices’ as the intimate relationship between three elements: materials (including infrastructure, tools, and objects), meanings (i.e., norms, ideologies, ethos, aspirations, perceptions, and symbolic meaning), and competences (i.e., skills and know-how). According to this conceptualisation, individuals are agents and ‘practitioners’ who combine these three constitutive elements in their practices [

16].

Notions with respect to intersectionality and social differentiation are vital to understanding practices associated with energy consumption, including the adoption of renewable energy technologies. Practices are internally differentiated, since practitioners in different cases may engage in the same practices differently [

17]. Forms of social difference, including ethnicity [

18], caste, class, age, religion, sexuality, the rural/urban divides, shape practices and energy adoption, while intersectionality examines how social power relations, based on forms of difference such as gender, class, age and race, are interconnected [

19,

20,

21,

22]. One form of difference derives its meaning through articulation with another, with individuals being actively engaged in the development of their identities [

23]. Cho et al. [

19] contended that intersectionality is “a way of thinking about the problem of sameness and difference”.

This framework is particularly suited for studies related to countries in nascent stages of electrification, such as those in South Asia, which usually rely on a combination of grid and off-grid energy. In South Asian countries, as we demonstrate later,

[…] practices are changing at a rapid pace too: not only in terms of what energy is consumed for and how, but also in regard to the reconfiguration of daily routines and practices around energy consumption, including family socialising or shifting household chores from early morning hours to evening.

3. Research Methods

A systematic review methodology was used to address the study’s research questions, i.e., How do categories of difference shape the uptake of SHSs in South Asia? How is energy generated by this technology used in households? Finally, how does the adoption of this technology reconfigure daily routines and practices? A systematic review attempts to gather all the relevant literature, based on pre-determined eligibility criteria, in order to answer a precise research question [

24]. Moreover, it clearly uses “systematic methods to minimize bias in the identification, selection, synthesis, and summary of studies” [

24]. As such, this study is guided by some core principles related to the systematic review process [

21,

25,

26,

27,

28].

3.1. Search Parameters

A systematic search of three multidisciplinary databases (i.e., Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect) was performed in May 2021. As shown in

Table 1, a Boolean search phrase which combined the following search terms, “solar pv”, “solar home system”, “solar photovoltaic panels”, “home solar”, “solar system”, and “solar photovoltaic system”, was used. I conducted a country-by-country search, meaning that all 8 South Asian country names (Bangladesh, Nepal, Afghanistan, Bhutan, Maldives, India, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan) were searched for in order to obtain the relevant literature related to these countries and to make sure that the search targeted literature related to these countries. The searches were carried out on 11 May 2021 (Web of Science), 13 May 2021 (Scopus), and 14 May 2021 (ScienceDirect).

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Several filters were used to identify papers that were relevant to the study by using pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. Only articles written in English and published in peer-reviewed academic journals were included, and editorials, conference proceedings, books, book reviews, book chapters, grey literature, and government reports were excluded. The selection of papers was not limited to a specific timeframe, meaning that all papers published by May 2021 were considered. Only papers related to the eight countries defined by the World Bank [

29] as part of the South Asian region were included. According to the World Bank [

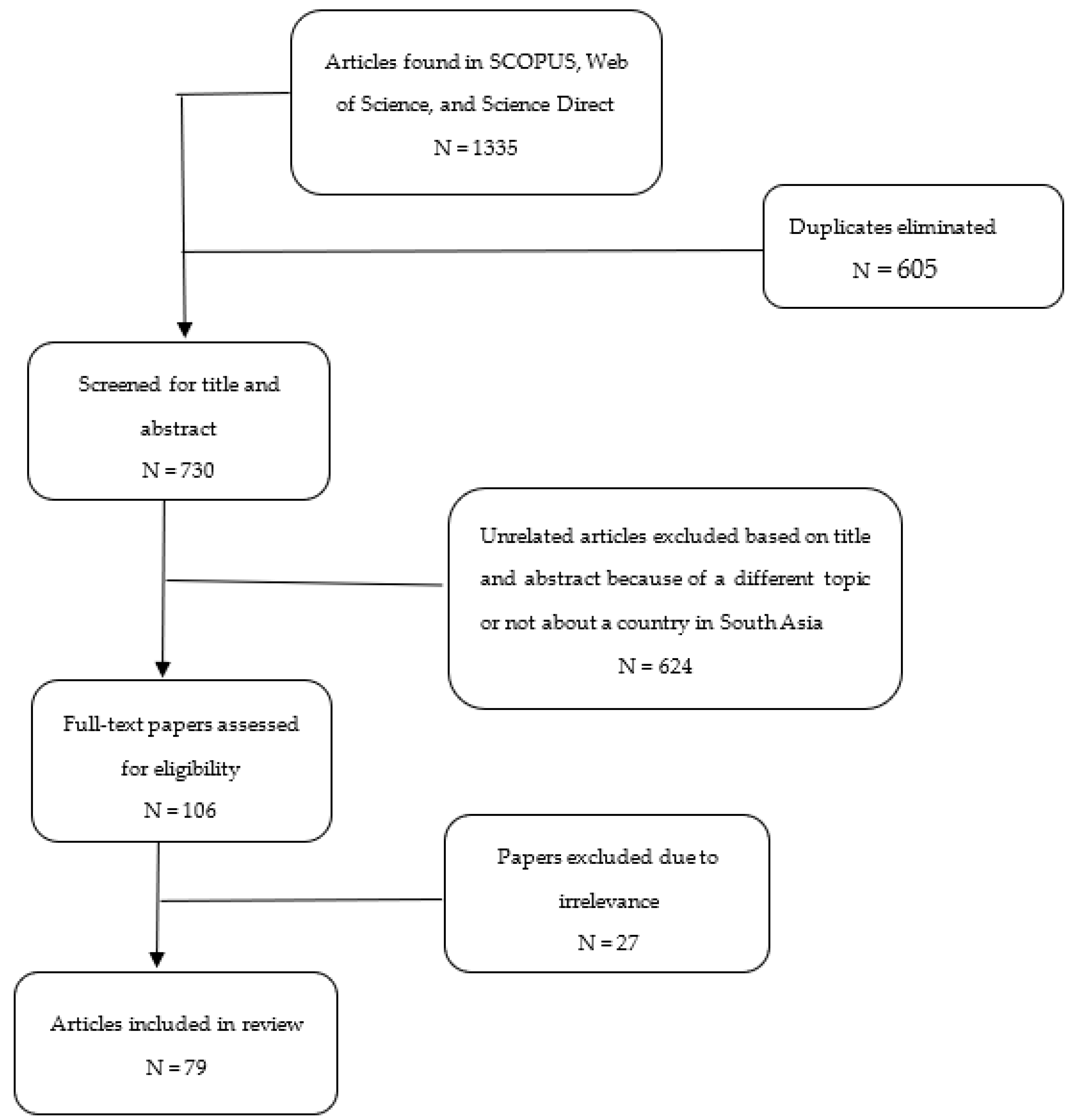

29], eight countries (India, Afghanistan, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Pakistan, and Nepal) belong to the South Asian region. Comparative studies which focused on the countries mentioned above, as well as any ineligible country, were included. Papers which solely focused on engineering features of SHSs were excluded. Papers which discussed SHSs alongside other energy technologies were included if the former was a significant component of the research. Papers were considered regardless of the type of data collected (quantitative, qualitative, or case study). A diagram of the literature search process is presented in

Figure 1.

A multistep process to select relevant papers was utilised. Duplicates were removed, and papers were systematically reviewed and included based on the relevance of their title and abstract to the aim of this research. A full-text review of the remaining articles to determine whether they met the eligibility criteria was conducted. The full-text review resulted in the exclusion of 27 papers. The final list of papers retrieved for review consisted of 79 papers.

An Excel file to capture certain features related to the papers, such as journal title, geographical location, and year of publication was used. Numerous a priori themes were explored as a way of starting the data analysis process of the study. The a priori themes were SHS adoption, energy consumption, and social practices. The qualitative data analysis software NVivo was used to organize, analyse, and code relevant insights related to the research questions.

4. Results

4.1. Background on Reviewed Papers

4.1.1. Distribution of Articles by Country

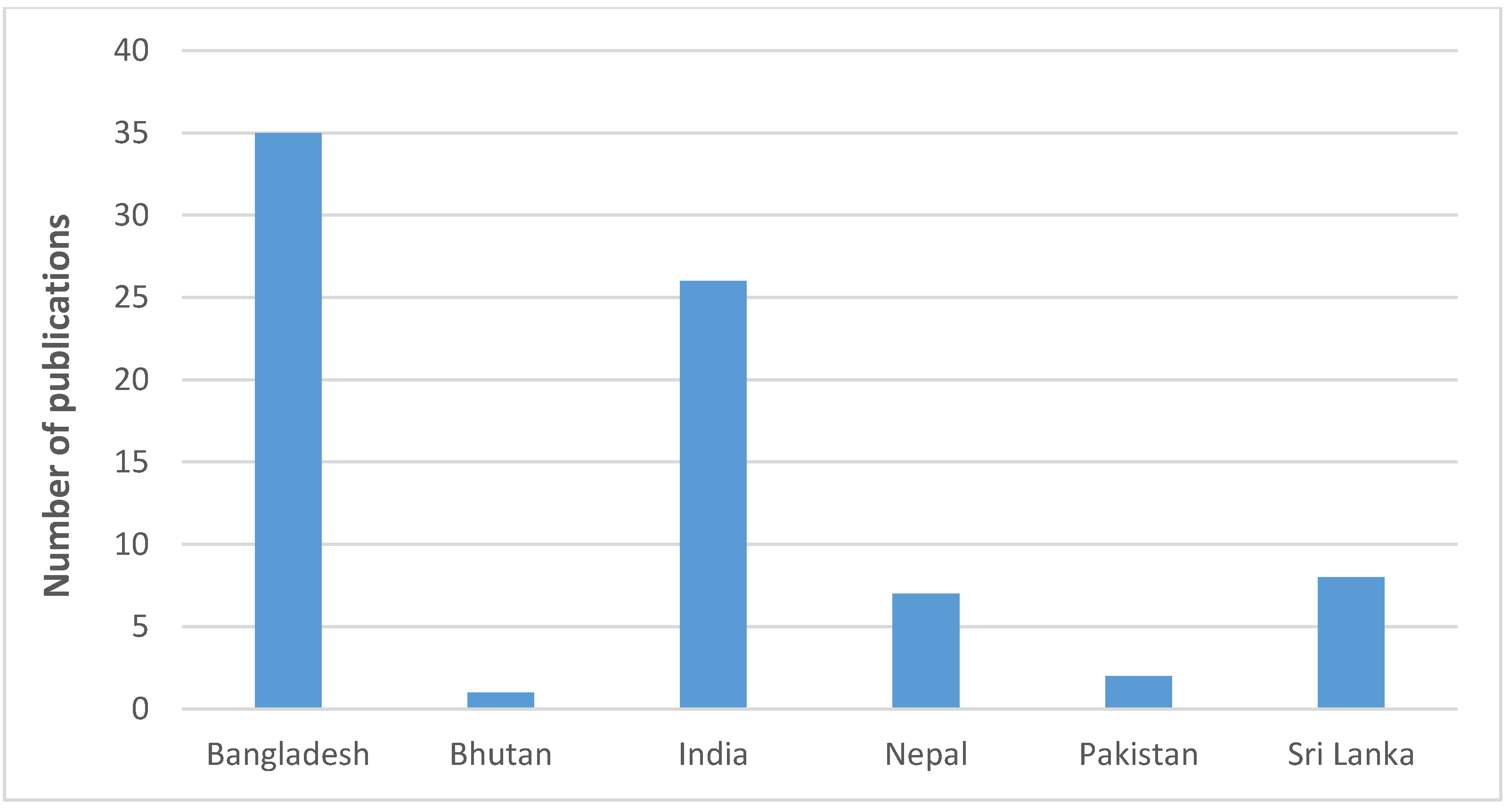

Although this study comprised all eight countries that make up the South Asian region, India and Bangladesh were the leading countries with respect to publications in academic journals (

Figure 2). Specifically, in terms of publications, India and Bangladesh were the leading countries at 33% and 44.3%, respectively, meaning that combined, these two countries accounted for 77.3% of all the papers in our sample. As shown in

Figure 2, while SHS-related studies have been carried out in other countries in South Asia (for example, Bhutan, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka), the number of papers associated with those countries remains relatively low, whereas other South Asian countries such as Afghanistan and the Maldives had no papers.

4.1.2. Publication Dates

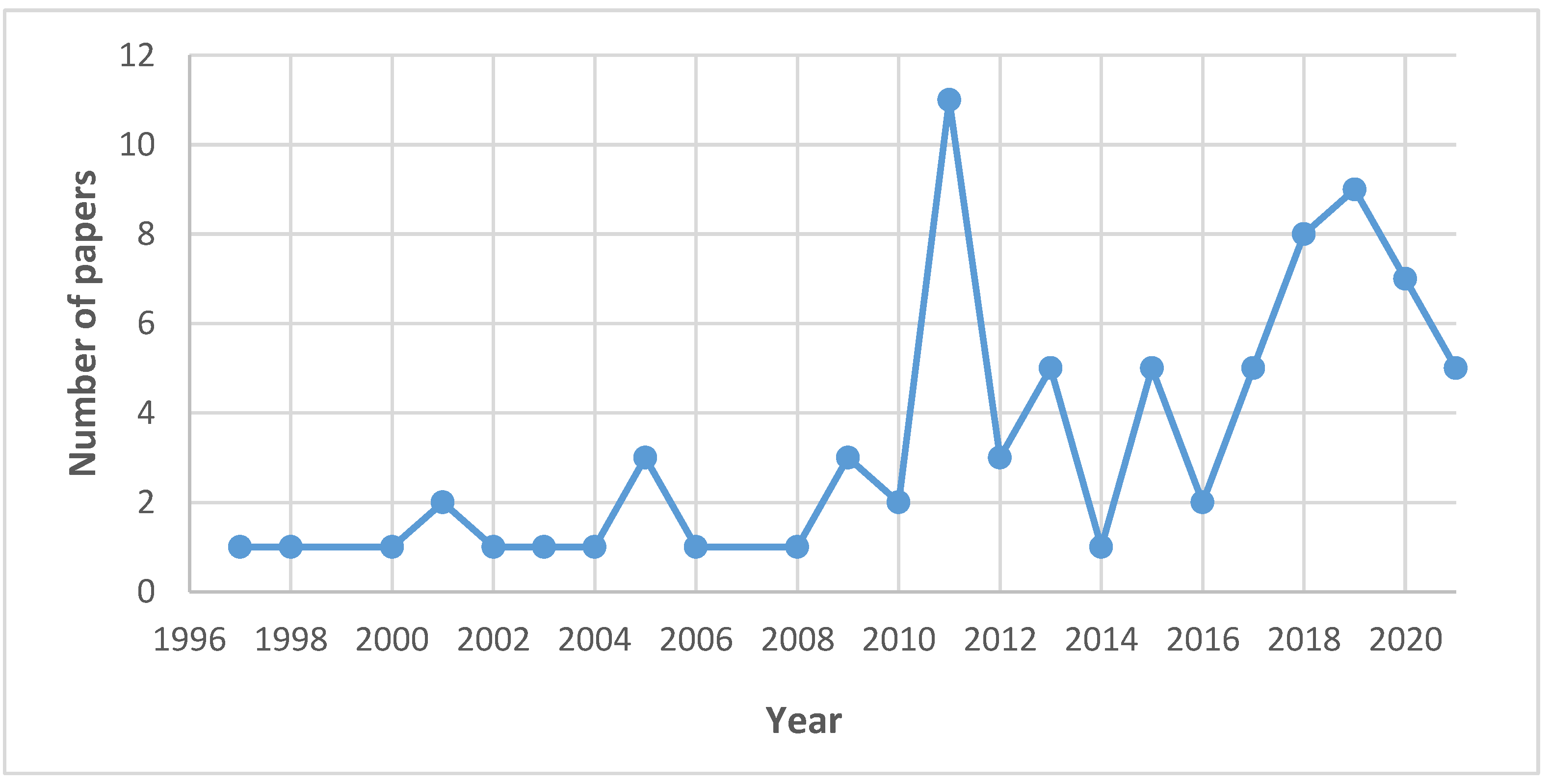

The number of SHS-related papers published in South Asia increased over the last decade, with 77.2% of papers in our review published between 2011 and (May) 2021. As shown in

Figure 3, fewer papers were published between 1997 (date of the first paper in our sample) and 2010. It is important to keep this background of the reviewed papers in mind when following discussions in subsequent sections.

4.2. SHS Adoption, Energy Consumption and Social Practices

In this section, we investigate how various dimensions of social difference influence the uptake of SHSs in various communities in South Asia. We also examine energy consumption in households and show how the adoption of SHSs reconfigures everyday routines and practices.

4.2.1. Social Differentiation and Adoption of SHSs

As shown in

Table 2, dimensions of difference such as gender, age, class, and ethnicity shape the adoption of SHSs in South Asia. The age of the household head, for example, has an influence on the adoption of SHSs. For example, a study conducted in Bangladesh found that older household heads spend more time at home, particularly at night, than younger household heads, and thus were more likely to install SHSs due to their greater need for electricity [

30]. Furthermore, another study carried out in Bangladesh showed that the ratio of elderly people in a household influenced the adoption of SHSs [

31]. Crucially, age intersects with other factors to influence SHS adoption. Aziz and Chowdhury [

30] noted that in Bangladesh, homes with elderly household heads who had fewer dependent children were more likely to adopt SHSs, as they had relatively greater discretionary incomes. In contrast, middle-aged household heads in Pakistan were more likely to install SHSs compared to elderly folks, as the latter were more risk-averse and therefore more reluctant to adopt new technologies [

32].

Additionally, gender intersects with educational status to influence the uptake of SHSs. In Bangladesh, households with women with higher levels of education were more likely to adopt SHSs, as they had more bargaining power and often used household appliances that required electricity [

30].

Class is another form of social difference that shapes the uptake of SHSs in South Asia. In some communities in South Asia, upper- and middle-class households that require more energy or are attempting to mitigate centralised grid power supply uncertainties are leading users of SHSs. In India, Nepal, and Pakistan, upper- and middle-class households were more likely to install SHSs than lower-class households [

32,

33,

34], whereas in Bangladesh, relatively well-off households were better positioned to purchase higher capacity SHSs [

35]. This was partly because they could afford the substantial down payment for the SHSs, while lower-class households could not meet this requirement [

36]. In Sri Lanka, some SHS providers offered users the opportunity to pay for the system in installments; however, some lower-class households with irregular incomes could not afford to pay the installments, leading to cases of repossession [

4]. The difference between lower- and middle-class households was not limited to urban communities. In rural Sri Lanka, those who purchased SHSs by paying cash tended to be middle- and upper-class households [

37]. Similarly, in India, the rural middle class were more likely to install SHSs, primarily to deal with the unavailability or uncertainties of grid electricity [

34]. So, in this case, class cuts across the rural-urban divide.

The adoption of SHSs is also shaped by the desire to attain or maintain one’s social status in the community. For households in Bangladesh, having solar-powered light, especially at night when other households are in darkness or using kerosene lamps or candles, was regarded as a symbol of social status [

38]. Other studies conducted in Nepal and Bangladesh noted that households adopted SHSs because it increased their social status [

39,

40,

41].

Furthermore, ethnicity was another form of social difference that influenced the adoption of SHSs. In Nepal, households who belonged to the Madhesi ethnic group were more likely to adopt SHSs than their counterparts from the Chhetri and Brahmin ethnic groups [

33], while in Sri Lanka, villages dominated by the Tamil ethnic group were more likely to adopt SHSs compared to Sinhalese villages [

42]. The latter authors noted that because the government was Sinhalese-dominated, coupled with a history of tension between Tamils and Sinhalese, the former avoided relying on the government for the provision of basic services, hence adopting SHSs [

42].

Table 2.

Forms of social difference and the uptake of SHSs.

Table 2.

Forms of social difference and the uptake of SHSs.

| Forms of Social Difference | Description | Included Papers |

|---|

| Age | The age of household head influences SHSs adoption, and older household heads are more likely to adopt SHSs. | [30,31] |

| Class | Upper- and middle-class households were more likely to adopt SHSs than lower-class households | [32,33,34,37] |

| Gender | Women with higher levels of education were more likely to adopt SHSs | [30] |

| Ethnicity | People’s ethnicity shape their likelihood of adopting SHSs | [33,42] |

4.2.2. Energy Consumption of SHS Adopters

SHS adopters often own electric appliances such as TVs, radios, DVD players, MP3 players, irons, rice cookers, kettles, fans, and stoves ([

4,

40,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. SHSs also enabled their owners to use such things as battery chargers, power drills, soldering irons, and water pumps [

36].

The adoption of SHSs triggers a gradual increase in energy consumption which is often beyond the capacity of the systems. In a study conducted in Bangladesh, a research participant referred to this trend as an addiction:

Once people get a SHS, for example, they want more services; it doesn’t stop with lights, they want a television, or if they already have a television, they want a color one, or if they have a lamp, they now want two, and they want them bigger and brighter. In this way an SHS is like a drug; it gets a household addicted to modern energy services, to convenience and comfort, but cannot always provide the energy needed to back that addiction.

In a similar vein, 43.4% of SHS adopters in India reported that their systems were unable to provide the energy required to fulfill their energy needs [

49].

The possession of electric appliances does not necessary translate into their use, as households sometimes possessed appliances which were often unused. In a study conducted in Sri Lanka, the authors noted that “SHSs provided predominantly a kind of ‘living-room power’: TV, stereo, phones and light, but not rice cookers, electric irons, spice-grinders or kettles” [

4]. In other words, the ability of people to use these appliances is based on the size of their SHS units. In Bangladesh, households with larger SHS units used appliances such as rice cookers, electric kettles, and electric stoves [

36]. Along similar lines, Caron [

50] found that owners of low-capacity SHSs in Sri Lanka were unable to power electric irons, whereas in India, low-income households tended only to acquire two-light systems [

51]. In Bangladesh, this segment of the population adopted SHSs with a 20 Watt-peak (Wp) capacity [

43], while in Nepal, about 83% of installed SHSs had a capacity below 40 Wp [

52]. In these cases, households may not be able to use some household appliances, as their systems do not have the capacity to power them.

That said, energy use by adopters of SHSs was distributed across the day. Often, lights were used the most in the evenings and at night [

39,

44,

47,

49], as were televisions [

4,

38,

53]. In Bangladesh, Barua et al. [

39] found that SHS adopters used TVs about 3-4 h per day. Mobile phone charging occurred at any time during the day, evening, or night [

31,

36,

40,

49,

54]. Yadav et al. [

55] noted that one of the main purposes for adopting SHSs in rural Bangladesh was to charge mobile phones; however, when or whether a phone was charged depended on the capacity of the SHSs.

Some users of low-capacity SHSs had to make choices with respect to how to use the energy. For instance, in Bangladesh, Saim and Khan [

56] found that as a result of the low capacity of some SHSs, adopters had to make a choice between charging a mobile phone or having light at night, as charging a mobile phone might mean that there would be insufficient energy to power the light bulbs. Fans were generally used during the day, especially in the afternoons [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59].

Energy consumption was higher among SHS adopters who used power from their systems for income-generating activities. Urmee and Harries [

40] found that some SHS adopters in Bangladesh generated income by charging the mobile phones of others in the community. Household-level income-generation activities such as hosting video shows and repairing electronics [

60] also contributed to increased energy consumption.

4.2.3. SHSs and Social Practices

As shown in

Table 3, the adoption of SHSs leads to changes in social practice. These changes also involve the capacity of systems and the fact that system batteries must be charged when there is sunshine in order to be used at certain times, especially at night, when there is no sunshine.

As noted earlier, the lighting of spaces was one of the principal reasons for people to adopt SHSs. Light was used for study, leisure, cooking, and eating [

31,

41,

43,

45,

48,

49,

54,

56,

61]. In rural India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh, children had longer study hours [

44,

53,

57,

61], and another study conducted in Bangladesh found that four hours were added to the study time of children in households with SHSs [

62].

The availability of light in the evening and at night also shaped leisure activities. This availability enabled families to spend more time together, including through eating and leisure practices such as having dinner and watching TV [

53,

60]. Time spent watching TV increased after the adoption of SHSs [

53]. Huq [

62] noted that following the adoption of SHSs, people in the southwestern coastal region of Bangladesh preferred watching TV over gossiping with neighbours. Spending time together was not restricted to intra-house members, and in rural Bangladesh, neighbours would regularly come to the homes of SHS adopters to watch TV [

44]. Still in Bangladesh, studies found that neighbours and relatives visited the houses of SHS adopters on a frequent basis to enjoy clean lighting and TV, and also stayed up later in the evening socialising with their hosts [

40,

46]. Additionally, the availability of light has led men to engage in reading at night, which was not the norm before SHS adoption. In Bangladesh, some men read books and newspapers even after 8 pm [

38,

62].

Table 3.

SHSs uptake and changes in social practices.

Table 3.

SHSs uptake and changes in social practices.

| Social Practices | Included Papers |

|---|

| Children had longer study hours after the adoption of SHSs | [44,53,57,62,63] |

| Families spent more time together | [53,60] |

| Time spent watching TV increased after the adoption of SHSs | [53] |

| Some people spent more time indoors watching TV than talking with neighours outside after SHS adoption | [62] |

| SHS adopters received frequent visits from neighbours and family members | [40,46] |

| Men read books and newspapers after 8 pm | [38,62] |

4.2.4. Flexibility in Relation to Practices

Our review shows flexibility regarding the performance of household chores (

Table 4). Millinger and Ahlgren [

57] found that in Chhattisgarh state in India, due to SHS adoption, women performed other activities during the day and rescheduled cooking dinner at a later time. Similarly, in Bangladesh, the availability of bright light enabled women to shift cooking to after dark [

45]. It is worth noting that in households which had adopted SHSs, not all women had solar light in their meal preparation spaces. This was the case of women in villages in the Sundarbans region of India. Murali et al. [

48] noted that:

while some women did not realize that there could be light in the kitchen, some felt it is more important to have light where their children study. Many women were found purposely not taken a connection in the kitchen because they felt that cooking takes just about an hour, which can be easily done with a kerosene lamp rather than using a light point, which otherwise can be used for reading by their children.

As noted briefly above, SHS adopters were also enabled to carry out income-generating activities at night. In Bangladesh, women carried out income-generating activities at home in the evening and at night, such as sewing, net-making, and performing repairs [

38,

39]. In India, following the adoption of SHSs, women engaging in homemade food businesses were able to extend their working hours into the evening and night [

49], similar to rural Bangladesh, where due to in-house lighting, some people extended their tailoring business activities [

63]. Rai [

60] found that in Nepal, some SHS adopters performed household-based income-generation activities such knitting/weaving, electronics repairs, and hosting video shows and tuition classes at night as a result of access to solar electricity.

Notably, SHSs reshaped certain outdoor practices. In the southwestern coastal region of Bangladesh, fishermen used SHSs in their boats to fish after dark and also used solar light to make nets and cages at night, while farmers used solar light on their farms to prevent rodents and other animals from destroying their crops [

63].

Table 4.

Flexibility in performing indoor and outdoor activities.

Table 4.

Flexibility in performing indoor and outdoor activities.

| Indoor and Outdoor Activities | Included Papers |

|---|

| Due to SHS adoption, women rescheduled cooking dinner for later in the evening. | [45,57] |

| SHS adopters carried out income-generating activities at night. | [38,39,60,64] |

| Fishermen used SHSs in their boats to fish after dark. | [63] |

5. Discussion

This study demonstrates that various dimensions of social difference, including gender, age, class, and ethnicity, intersect and shape the uptake of SHSs in South Asia. Furthermore, it shows that the uptake of SHSs has changed some practices of both SHS adopters and non-SHS adopters, while other practices remained unchanged. Additionally, people adapt SHSs to meet their needs. In the section that follows, I bring to the fore the study’s major findings, identify research gaps, and discuss its limitations.

5.1. Reflections on the Study’s Findings

The findings offer vital insights on the adoption of SHSs in several locations in South Asia. First, whether people adopt SHSs is based on various non-economic factors. The evidence from this study suggests that in various communities in South Asia, categories of difference such as gender, class, ethnicity, and age shape the adoption of SHSs. However, these factors are often overlooked in favour of economic factors such as people’s financial situations. The point we are stressing here is that in addition to economic factors, forms of social difference equally frame people’s decisions to adopt SHSs. As mentioned earlier, certain ethnic groups in Nepal and Sri Lanka were more likely to adopt SHSs than others [

33,

42].

Furthermore, the uptake of SHSs was linked to people’s desire to maintain or elevate their social status [

39,

40,

41]. In other words, SHSs are not just technical tools which give people access to clean energy, they also come with a meaning which denotes that adopters belong to a particular social class. Arguably, in this case, the adoption of SHSs was guided by goals with social meaning to the adopters. This corroborates Gram-Hanssen’s [

65] argument that people attach meaning to domestic energy practices.

Second, SHS adoption leads to changes in practices. As mentioned earlier, the desire to charge mobile phones was one of the key reasons why people adopted SHSs in various communities in South Asia [

31,

40,

49,

54,

55]. Prior to the installation of SHSs, individuals used to charge their phones in shops and marketplaces, paying a fee for the service [

44,

45,

49], while following SHS adoption, they would charge their mobile phones at home. In other words,

[…] having a SHS moves the practice of charging phones externally at a shop or a charging station […] and brings it into the home, allowing for more flexibility of when to do it and eliminating the need to take a trip out to have it charged.

Additionally, the changes in practices had a spatial dimension. SHS adopters changed from socialising with neighbours externally to socialising with family members and neighbours indoors, at times while watching TV [

44,

63]. Arguably, this spatial change is also indicative of their elevated social status. Put differently, socialising with family members and neighbours indoors may be reflective of the elevated social statuses of SHS adopters. The point we are emphasising here is that based on the socio-cultural context, while SHS adoption may have a practical function, there equally exists a symbolic one. Scholars contend that energy-related practices are embedded in society and are hence shaped by culture and meanings [

7,

66].

Crucially, the uptake of SHSs by some households also changed the practices of individuals in households which had not adopted these systems. Individuals who had not adopted SHSs visited the homes of SHS adopters on a regular basis [

40,

46]. The fact that these individuals began visiting the homes of people who had recently installed SHSs indicates a change in the practices of the non-SHS adopters. Their leisure time was spent indoors in the homes of the SHS adopters, and in most cases, the guests and hosts socialised while watching TV. Furthermore, the practices of non-SHS adopters changed with respect to where they charged their mobile phones. Non-adopters changed from charging their mobile phones in shops and charging stations, where they had to pay for the service, to charging them in the homes of SHS adopters, as reflected in a study conducted in Bangladesh which noted that neighbours visited the homes of SHS adopters to charge their mobile phones [

56].

It must be noted, however, that in some instances SHS adoption may weaken relationships between members of a neighbourhood. At times, SHS adopters have to decline requests from neighbours to charge a phone, especially when the SHS system’s battery is not charged [

56] and declining the request may negatively affect the social relationship between the parties.

Third, whether practices change is also based on the capacity of SHSs. Low-capacity SHSs may be unable to power household appliances such as electric irons, rice cookers, spice-grinders, kettles, etc. [

4]. These are appliances mostly used by women, and their use facilitates the performance of household chores and saves time, which suggests that in households that adopt low-capacity SHSs, there may be no changes in practices related to cooking and ironing, for example. This equally suggests that from an intra-household perspective, there are variations with respect to changes in practices, and these variations bring to the fore the fact that forms of social difference also contribute to shaping the degrees of change in practices.

Fourth, SHSs are embedded in the local socio-economic context, and consequently, the local context shapes how people use power generated by the systems. Earlier, it was mentioned that some fishermen and farmers in Bangladesh used SHSs in their boats to fish after dark and on their farms to prevent rodents and other animals from destroying their crops [

63]. It is our contention here that the SHSs were adjusted to the context in which the adopters lived. People constantly adapt new technologies, and in this case, renewable energy technologies are adapted and change their users’ ways of doing things. Old practices are gradually transformed as renewable energy technologies create new opportunities, and scholars have noted that people often alter and improvise renewable energy products in creative ways to meet their everyday needs [

67,

68].

5.2. Gaps and Future Research Agendas

This study has generated major insights and has equally identified relative blind spots in the scholarly literature which could be the focus of future studies. South Asia is composed of several countries, but a high proportion of studies on SHSs in the region have been conducted on only a few. According to this review, a high proportion of studies were carried out in two countries, i.e., India and Bangladesh, and hence I am making a call for research to be conducted in those countries which have received relatively little attention, since they are diverse economically, politically, and socio-culturally. Additionally, researchers should study various issues in the SHS space from a socio-cultural angle, as this would provide nuanced and in-depth understandings on major issues related to the use of this technology in the region.

The intimate connection between gender and other dimensions of social difference, such as caste, ethnicity, and religion, and their influence on the adoption of SHSs and energy consumption practices, has also received little scholarly attention in South Asia. There is a tendency for studies to centrally focus on the economic factors which shape the uptake of SHSs while overlooking the facets of social difference, which are equally important. Researchers might, for example, consider examining this under-researched phenomenon from an intersectional perspective. Furthermore, Hoicka et al. [

69] noted that Indigenous peoples in Canada have also been engaged in renewable energy production, so future studies could examine how various facets of social difference intersect and influence SHS adoption in Indigenous communities in South Asia. Studies could also look at energy-related practices in these communities. Using “situated knowledge grounded in the reality of everyday life as a source of data” [

70] would challenge the conventional narrative on renewable energy technologies adoption in these communities.

Moreover, how the uptake of SHSs by some households changes the practices of others in the local community who have not adopted them has received little attention within the academic literature. There is a significant body of work on the practices of SHS adopters, and while this is laudable, research on how the practices of non-adopters in the community are changed would enrich the literature on social practices in the renewable energy sphere.

Finally, institutions are particularly important to the adoption of renewable energy technologies, including the consumption of renewable energy [

71]. However, studies have devoted little attention to the institutional designs required for transition to renewable energy in South Asian countries. Researcher might, for instance, examine the institutions that are need for sustainable energy in different countries in the region.

5.3. Limitations of the Review

I have identified a few limitations related to this study. First, in this study, I used social practice theory and intersectionality lenses to examine SHS uptake, energy consumption, and social practices, and I acknowledge that investigating the uptake of SHSs as well as emerging practices related to their adoption through alternative frameworks may have given rise to different findings. However, the social practice theory and intersectionality perspectives were appropriate for providing answers to the research questions.

Second, the Boolean search phrase I used may have missed some papers on SHSs in South Asia. I attempted to minimise this limitation by using three major databases (i.e., Scopus, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science) to carry out a search of relevant articles. In addition, regarding the inclusion and coding of relevant literature, researchers have contended that a systematic review is well-suited for “relatively narrow research questions” [

25].

Third, because of time constraints, I limited this review to peer-reviewed articles published in academic journals [

20]. In other words, I excluded grey literature and government reports, which may have provided very interesting insights on SHSs in the region. However, unlike previous systematic reviews which limited their search to articles published in journals with an impact factor [

72], this research considered all papers accessible through the principal databases of ScienceDirect, Scopus, and Web of Science. As such, I am of the view that this review contributes to the scholarly literature on SHS adoption, energy consumption behaviours, and changing social practices of SHS users in South Asia.

Fourth, this study has language limitations, since only papers written in English were selected. This means that articles published in various other languages used in the region (e.g., Bengali, Hindi, Nepali, Panjabi, Pali, and Sinhala) were excluded. Nonetheless, I am of the view that this study captured a high percentage of studies on solar home systems in South Asia, as a high proportion of researchers publish their work in English in order to reach a wide audience.

6. Conclusions

The purpose of this study lies in understanding energy consumption behaviours as well as the social elements of SHS adoption and energy use in households that have adopted these products. Based on a systematic review approach, 79 peer review articles related to the study’s research questions were reviewed, and the analysis generated three key findings.

First, the adoption of SHSs is not driven solely by economic factors, as different dimensions of social difference such as gender, age, class, and ethnicity shape the likelihood of people adopting these systems, and also influence how energy generated by SHSs is used in the household in various communities in South Asia. It is partly because of these forms of social difference that in some households, women did not really benefit from the uptake of SHSs due to their inability to use electrical household appliances such as rice cookers, blenders, and kettles, which are vital for cooking, because of the low capacity of their systems. This finding has implications for policy and programme designs aiming to promote the adoption of SHSs in South Asia. Policies that support subsidies, for instance, may serve to address the financial constraints faced by some households to adopt SHSs, but more targeted programmes are necessary to ensure that low-income households can access high-capacity SHSs that will enable them to use various household appliances, thus maximise the impact of these products. This highlights the importance of adopting an intersectional lens when designing policies and programmes aimed at promoting a shift in energy consumption and associated practices in the region.

Second, as seen from a social practice perspective, SHSs play a pivotal role in shaping, and in turn being shaped by, the spatial and temporal practices of adopters and non-adopters in communities in South Asia. Certain practices which were previously usually done in the daytime shifted to the evening and nighttime, while other practices which used to take place outside of the home moved indoors. Because SHS adopters are part of a community, the installation of SHSs in their homes also changed the practices of others in their community. This has certain implications, as it shows that the diffusion and use of renewable energy technologies generates changes not only in the lives of the direct adopters, but also in the lives of community members who have not adopted these technologies. SHSs were also reconfigured to match the spatial and temporal practices of the adopters, and here we see the dynamics between materiality (SHSs), context, and agency.

Third, based on the economic and socio-cultural contexts, the adoption of SHSs involves both practical and symbolic functions. The potential economic and social benefits of SHSs are usually used to encourage the adoption of SHSs, while the symbolic benefit of these systems is very often overlooked. However, in various communities in South Asia, SHSs have another meaning: they are connected to social status. In other words, SHSs have a social meaning, and it is based on this social meaning that SHS adopters may enjoy an elevated social status in their communities. This implies that renewable energy technologies such as SHSs cannot be considered just as simple technical systems that enable access to clean energy, rather they are markers of social hierarchies and social worth which take specific forms according to the local context.