The Influence of Personal Involvement on Festival Attendees’ Revisit Intention: Food and Wine Attendees’ Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Motivations as Antecedents of Personal Involvement

2.2. Consumer Involvement Dimensions in Festivals

2.3. The Relationship Between Motivation and Involvement, Satisfaction, and Revisit Intentions

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Research Instrument Design

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

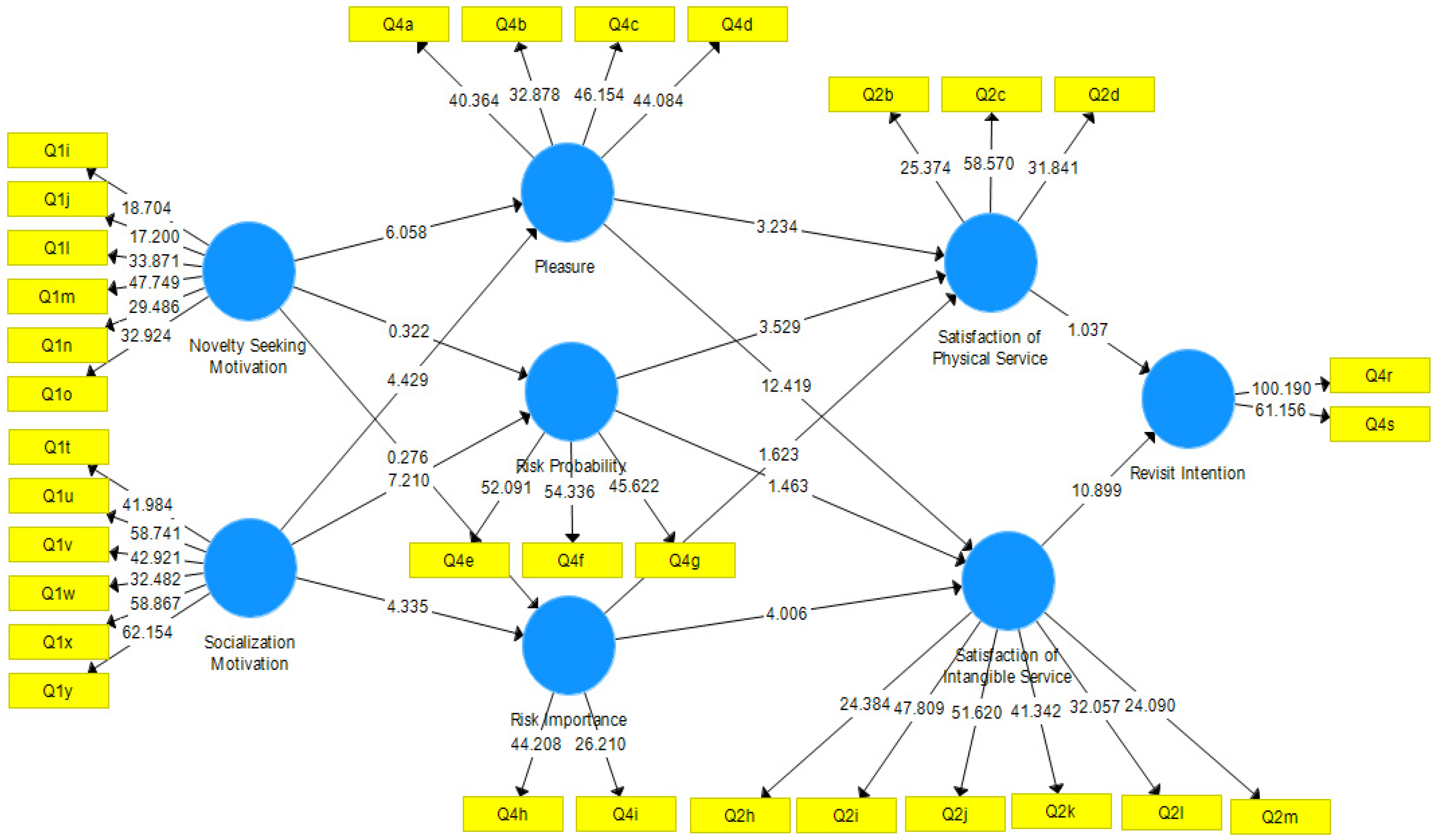

4.2. Partial Least Squares Analysis (PLS)

4.3. Individual Hypothesis Testing

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, K.; Reisinger, Y.; Kang, H. Visitors’ Motivation for Attending the South Beach Wine and Food Festival, Miami Beach, Florida. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 25, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passport for Your Tastebuds: The Rise of Food Tourism Across the Globe. 2017. Available online: https://www.cheapoair.com/miles-away/the-rise-of-food-tourism-across-the-globe (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Lee, H.; Hwang, H.; Shim, C. Experiential festival attributes, perceived value, satisfaction, and behavioral intention for Korean festivalgoers. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 19, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Hall, C.M. Wine Tourism Research: The State of Play. Tour. Rev. Int. 2006, 9, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.S.; Gao, H. Developing Australia’s food and wine tourism towards the Chinese visitor market. In Food, Wine and China: A Tourism Perspective; Pforr, C., Phau, I., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 112–132. [Google Scholar]

- Attanasi, G.; Bortolotti, S.; Cicognani, S.; Filippin, A. The Drunk Side of Trust: Social Sapital Generation at Gathering Events (No. 2017-21); Bureau d’Economie Théorique et Appliquée, UDS: Strasbourg, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, J.L.; McKay, S.L. Motives of visitors attending festival events. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Spangenberg, E.R.; Rutherford, D.G. The hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of attendees; attitudes toward fes-tivals. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, P.T.; Perdue, R.R. The economic impact of rural festivals and special events: Assessing the spatial distribution of ex-penditures. J. Travel Res. 1990, 28, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, C.-K.; Choi, Y. Examining the Role of Emotional and Functional Values in Festival Evaluation. J. Travel Res. 2010, 50, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Mei, W.S.; Tse, T.S.M. Are short duration cultural festivals tourist attractions? J. Sustain. Tour. 2006, 14, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanasi, G.; Casoria, F.; Centorrino, S.; Urso, G. Cultural investment, local development and instantaneous social capital: A case study of a gathering festival in the South of Italy. J. Socio-Econ. 2013, 47, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanardi, M.; Lucarelli, A.; Decosta, P.L. Co-performing tourism places: “Pink Night” festival. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 44, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanasi, G.; Passarelli, F.; Urso, G.; Cosic, H. Privatization of a Tourism Event: Do Attendees Perceive it as a Risky Cultural Lottery? Sustainability 2019, 11, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Sung, H.; Suh, E.; Zhao, J. The effects of festival attendees’ experiential values and satisfaction on revisit intention to the destination: The case of a food and wine festival. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1005–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, N. Festival connections: How consistent and innovative connections enable small-scale rural festivals to contribute to socially sustainable communities. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2016, 7, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadri-Felitti, D.; Fiore, A.M. Wine tourism suppliers’ and visitors’ experiential priorities. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebensen, N.K.; Woo, E.; Chen, J.; Uysal, M. Motivation and Involvement as Antecedents of the Perceived Value of the Destination Experience. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; So, S.I.; Chakravarty, S. To wine or not to wine: Profiling a wine enthusiast for a successful list. J. Nutr. Recipe Menu Dev. 2005, 3, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žabkar, V.; Brencic, M.M.; Dmitrovic, T. Modelling perceived quality, visitor satisfaction and behavioral intentions at the destination level. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 537–546.zv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasian, S.; Lundberg, A. Between Fire and Ice: Experiences of the Persian Fire Festival in a Nordic Setting. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, C.; Silva, G.M.; Gonçalves, H.; Duarte, M. The role of motivations and involvement in wine tourists’ intention to return: SEM and fsQCA findings. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 89, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, S.; Rootenberg, C.; Ellis, S. Examining the Influence of the Wine Festival Experience on Tourists’ Quality of Life. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 111, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Zhang, H.Q.; King, B.; Huang, S. (Sam) Wine tourism involvement: A segmentation of Chinese tourists. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 633–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitterlin, M.; Yoo, M. Festival motivation and loyalty factors. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2014, 10, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Goossens, C. Tourism information and pleasure motivation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Alant, K. The hedonic nature of wine tourism consumption: An experiential view. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alant, K.; Bruwer, J. Wine tourism behavior in the context of a motivational framework for wine regions and cellar doors. J. Wine Res. 2004, 15, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Brown, G. Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.J.; Cai, L.A.; Morrison, A.M.; Linton, S. An analysis of wine festival attendees’ motivations: A synergy of wine, travel and special events? J. Vacat. Mark. 2005, 11, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, P.H. Relationships between global and specified measures of novelty seeking. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1970, 34, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havitz, M.; Dimanche, F. Propositions for guiding the empirical testing of the involvement construct in recreational and tourist context. Leis. Sci. 1990, 12, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opatow, L.; Sherif, C.W.; Sherif, M.; Nebergall, R.E. Attitude and Attitude Change. J. Mark. Res. 1966, 3, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal, R.; Havitz, M.E.; Howard, D.R. Married couples’ involvement with family vacations. Leis. Sci. 1992, 14, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclntyre, N.; Pigram, J.J. Recreation specialization reexamined: The case of vehicle-based campers. Leis. Sci. 1992, 14, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, M.J.; Rothschild, M.L. Conceptual and methodological perspectives on involvement. In 1978 Educators’ Proceedings; Jain, S.C., Ed.; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1978; pp. 184–187. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.-Y.; Chou, C.-J.; Lin, P.-C. Involvement theory in constructing bloggers’ intention to purchase travel products. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the Involvement Construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.C.; Durvasula, S.; Akhter, S.H. A Framework for Conceptualizing and Measuring the Involvement Construct in Advertising Research. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J.N.; Laurent, G. Consumer involvement profiles: A new practical approach to consumer involvement. J. Advert. Res. 1985, 25, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D.; Gavcar, E. International leisure tourists’ involvement profile. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 906–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimanche, F.; Havitz, M.E.; Howard, D.R. Testing the Involvement Profile (IP) Scale in the Context of Selected Recreational and Touristic Activities. J. Leis. Res. 1991, 23, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.T.; Absher, J.D.; Hammitt, W.E.; Cavin, J. An Examination of the Motivation—Involvement Relationship. Leis. Sci. 2006, 28, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, Y.; Havitz, M.E. A Path Analytic Model of the Relationships between Involvement, Psychological Commitment, and Loyalty. J. Leis. Res. 1998, 30, 256–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouthouris, C. An examination of the relationships between motivation, involvement and intention to continuing participation among recreational skiers. Int. J. Sport Manag. Recreat. Tour. 2009, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, D. The Effect of Food Tourism Behavior on Food Festival Visitor’s Revisit Intention. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, D.; Ridinger, L.L.; Moorman, A.M. Exploring Origins of Involvement: Understanding the Relationship Between Consumer Motives and Involvement with Professional Sport Teams. Leis. Sci. 2004, 26, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.-C.; Lee, B.; Park, M.; Stokowski, P.A. Measuring Underlying Meanings of Gambling from the Perspective of Enduring Involvement. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Beeler, C. An Investigation of Predictors of Satisfaction and Future Intention: Links to Motivation, Involvement, and Service Quality in a Local Festival. Event Manag. 2009, 13, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, M.; Palmer, A.; Charters, S. Wine production as a service experience—The effects of service quality on wine sales. J. Serv. Mark. 2002, 16, 342–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, S.K.; Babin, B.J. Festivalscapes and patrons’ emotions, satisfaction, and loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnick, R.; Sutton, W.; McDonald, M. Female Golfers and Clothing Interests: An Examination of Involvement Theory; Unpublished Manuscript; University of Massachusetts at Amherst: Amherst, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Marković, S. How Festival Experience Quality Influence Visitor Satisfaction? A Quantitative Approach. Naše Gospodarstvo/Our Economy 2019, 65, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, E.; Palmatier, R.; Steenkamp, J. Effect of service transition strategies on firm value. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Goh, B.K.; Yuan, J. Development of a Multi-Dimensional Scale for Measuring Food Tourist Motivations. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2010, 11, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddleston, P.; Whipple, J.; VanAuken, A. Food store loyalty: Application of a consumer loyalty framework. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 2003, 12, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, B.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed.): A Global Perspective; Pearson Education Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Roldán, J.L.; Sánchez-Franco, M.J. Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling: Guidelines for Using Partial Least Squares in Information Systems Research. In Research Methodologies, Innovations and Philosophies in Software Systems Engineering and Information Systems; Mora, M., Gelman, O., Steenkamp, A.L., Raisinghani, M.S., Eds.; Information Science Reference: Hershey, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 193–221. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Newsted, P.R. Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. Stat. Strat. Small Sample Res. 1999, 2, 307–341. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, vii–xvi. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/249674 (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Peter, J.P.; Churchill, G.A. Relationships among Research Design Choices and Psychometric Properties of Rating Scales: A Meta-Analysis. J. Mark. Res. 1986, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended tow-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Tutorials Quant. Methods Psychol. 2007, 3, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tkaczynski, A.; Stokes, R. Festperf: A Service Quality Measurement Scale for Festivals. Event Manag. 2010, 14, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic Description | Group | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (n = 432) | Male | 37.5% (162) |

| Female | 62.5% (270) | |

| Age (n = 434) | 21–24 years | 13.6% (59) |

| 25–34 years | 26.5% (115) | |

| 35–44 years | 25.1% (109) | |

| 45–54 years | 20.7% (90) | |

| 55–64 years | 10.6% (46) | |

| 65 plus | 3.5% (15) | |

| Education (n = 386) | High school | 6.7% (26) |

| Associate’s Degree | 14.5% (56) | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 38.1% (147) | |

| Master’s Degree | 25.9% (100) | |

| Doctoral Degree | 8.5% (33) | |

| Other Education/Trade | 6.2% (24) | |

| Marital status (n = 424) | Single | 38.4% (163) |

| Married | 47.9% (203) | |

| With Partner | 13.7% (58) | |

| Annual Family Income (n = 422) | 39,999 USD or less | 10.9% (46) |

| 40,000–79,999 USD | 25.1% (106) | |

| 80,000–119,999 USD | 19.4% (82) | |

| 120,000–159,999 USD | 9.5% (40) | |

| 160,000–199,999 USD | 9.7% (41) | |

| 200,000 USD and over | 14.7% (62) | |

| I respectfully decline to answer | 10.7% (45) | |

| Ethnicity (n = 426) | Caucasian (Non-Hispanic) | 50% (213) |

| African American/Black (Non-Hispanic) | 10.6% (45) | |

| Hispanic | 30.8% (131) | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 3.5% (15) | |

| American Indian | 1.6% (7) | |

| Mixed Ethnicities | 3.3% (15) | |

| Is this your first visit to this | Yes | 49.7% (213) |

| event? (n = 429) | No | 50.3% (216) |

| Construct | Items | Loading | ICR | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novelty Seeking Motivation | I like the variety of things to see and do | 0.881 | 13.004 | |

| To experience new and different things | 0.830 | 8.738 | ||

| Enjoy special events/festivals | 0.721 | 13.285 | ||

| Festivals are stimulating and exciting | 0.691 | 8.574 | 0.860 | |

| This festival is unique | 0.618 | 14.157 | ||

| I was curious about this festival | 0.568 | 10.907 | ||

| Socialization Motivation | To be with people of similar interest | 0.848 | 12.380 | |

| To be with people who enjoy the same things I do | 0.816 | 13.910 | ||

| For chance to be with people who are enjoying themselves | 0.791 | 11.801 | 0.914 | |

| To see the entertainment | 0.790 | 13.160 | ||

| I enjoy festival crowds | 0.765 | 10.955 | ||

| To observe other people attending the festival | 0.731 | 12.456 | ||

| Pleasure | I have a strong interest in the food and wine | 0.817 | 11.824 | |

| I attach a great importance to the food and wine | 0.785 | 12.521 | ||

| The experience of the food and wine festival is somewhat a pleasure to me | 0.746 | 12.964 | 0.844 | |

| Buying the ticket of the food and wine festival is like buying a gift for myself | 0.713 | 12.780 | ||

| Risk Probability | Choosing a food and wine festival to attend is rather complicated | 0.862 | 10.832 | |

| When I buy a ticket of the food and wine festival, I am never certain of my choice | 0.781 | 11.004 | ||

| When I face a variety of food and wine festival choices, I always feel a bit at loss to make my choice | 0.759 | 7.638 | 0.840 | |

| Risk Importance | It is really annoying to attend a food and wine festival that is not suitable | 0.823 | 9.047 | |

| If, after I bought a ticket of the food and wine festival, my choice proves to be poor, I would be really upset | 0.670 | 11.467 | 0.711 | |

| Satisfaction with Physical Services | Program pamphlets | 0.873 | 12.487 | |

| Festival programs and schedules | 0.845 | 9.917 | ||

| Signage for directions | 0.783 | 14.223 | ||

| Book signings | 0.719 | 11.013 | 0.801 | |

| Festival staff knowledge | 0.628 | 14.179 | ||

| Festival staff helpfulness | 0.561 | 4.244 | ||

| Satisfaction with Intangible Services | Restrooms | 0.861 | 12.998 | |

| Rest areas | 0.791 | 6.376 | 0.885 | |

| Parking | 0.636 | 13.327 | ||

| Revisit Intention | I will spread positive word-of-mouth about the festival in Miami, Florida | 0.866 | 9.312 | 0.831 |

| I will keep attending the festival held in Miami, Florida | 0.823 | 6.585 | ||

| χ2 = 1131.870, df = 431. p = 0.000, RMSEA = 0.060, GFI = 0.861, 2AGFI = 0.830, CFI = 0.918, FI = 0.919, TLI = 0.906. | ||||

| Variables | Cronbach’s Alpha | Adjusted R2 | Rho_A | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novelty Seeking Motivation (NM) | 0.870 | 0.877 | 0.871 | 0.532 | |

| Socialization Motivation (SM) | 0.916 | 0.919 | 0.915 | 0.643 | |

| Pleasure (P) | 0.850 | 0.328 | 0.850 | 0.850 | 0.586 |

| Risk Probability (RP) | 0.840 | 0.192 | 0.842 | 0.840 | 0.637 |

| Risk Importance (RI) | 0.711 | 0.083 | 0.742 | 0.722 | 0.569 |

| Satisfaction with the Physical Services (SPS) | 0.801 | 0.144 | 0.809 | 0.804 | 0.578 |

| Satisfaction with the Intangible Service (SIS) | 0.885 | 0.477 | 0.886 | 0.885 | 0.562 |

| Revisit Intention (RVI) | 0.833 | 0.273 | 0.837 | 0.834 | 0.716 |

| AVE | Variables | NM | SM | P | RP | RI | SPS | SIS | RVI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.532 | Novelty Seeking Motivation (NM) | 0.730 * | |||||||

| 0.643 | Socialization Motivation (SM) | 0.598 | 0.802 * | ||||||

| 0.586 | Pleasure (P) | 0.543 | 0.477 | 0.765 * | |||||

| 0.637 | Risk Probability (RP) | −0.226 | −0.440 | −0.438 | 0.798 * | ||||

| 0.569 | Risk Importance (RI) | −0.147 | −0.294 | −0.344 | 0.483 | 0.754 * | |||

| 0.578 | Satisfaction with the Physical Services (SPS) | 0.289 | 0.393 | 0.306 | −0.335 | −0.252 | 0.761 * | ||

| 0.562 | Satisfaction with the Intangible Services (SIS) | 0.499 | 0.517 | 0.669 | −0.361 | −0.399 | 0.470 | 0.750 * | |

| 0.716 | Revisit Intention (RVI) | 0.428 | 0.294 | 0.754 | −0.206 | −0.227 | 0.169 | 0.519 | 0.846 * |

| Hypotheses | STDEV | ß | f2 | T | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Novelty Seeking Motivation → Pleasure | 0.056 | 0.340 | 0.112 | 6.058 | 0.000 |

| H1b | Novelty Seeking Motivation → Risk Probability | 0.060 | 0.019 | 0.000 | 0.322 | 0.748 |

| H1c | Novelty Seeking Motivation→ Risk Importance | 0.058 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.276 | 0.783 |

| H1d | Socialization Motivation→ Pleasure | 0.054 | 0.239 | 0.055 | 4.429 | 0.000 |

| H1e | Socialization Motivation → Risk Probability | 0.055 | −0.397 | 0.132 | 7.210 | 0.000 |

| H1f | Socialization Motivation → Risk Importance | 0.058 | −0.251 | 0.048 | 4.335 | 0.000 |

| H2a | Pleasure → Satisfaction with Physical Services | 0.051 | 0.163 | 0.025 | 3.234 | 0.001 |

| H2b | Pleasure → Satisfaction with Intangible Servcies | 0.041 | 0.515 | 0.355 | 12.419 | 0.000 |

| H2c | Risk Probability → Satisfaction with Physical Services | 0.053 | −0.185 | 0.030 | 3.529 | 0.000 |

| H2d | Risk Probability → Satisfaction with Intangible Servcies | 0.041 | −0.060 | 0.004 | 1.463 | 0.144 |

| H2e | Risk Importance → Satisfaction with Physical Services | 0.049 | −0.080 | 0.006 | 1.623 | 0.105 |

| H2f | Risk Importance → Satisfaction with Intangible Servcies | 0.040 | −0.160 | 0.034 | 4.006 | 0.000 |

| H3a | Satisfaction with Physical Servcies → Revisit Intention | 0.045 | −0.046 | 0.002 | 1.037 | 0.300 |

| H3b | Satisfaction with Intangible Servcies → Revisit Intention | 0.043 | 0.465 | 0.228 | 10.899 | 0.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, W.; Kwon, H. The Influence of Personal Involvement on Festival Attendees’ Revisit Intention: Food and Wine Attendees’ Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147727

Lee W, Kwon H. The Influence of Personal Involvement on Festival Attendees’ Revisit Intention: Food and Wine Attendees’ Perspective. Sustainability. 2021; 13(14):7727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147727

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Woojin, and Haeyoon Kwon. 2021. "The Influence of Personal Involvement on Festival Attendees’ Revisit Intention: Food and Wine Attendees’ Perspective" Sustainability 13, no. 14: 7727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147727

APA StyleLee, W., & Kwon, H. (2021). The Influence of Personal Involvement on Festival Attendees’ Revisit Intention: Food and Wine Attendees’ Perspective. Sustainability, 13(14), 7727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147727