Sustainability in Refugee Camps: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Definitions

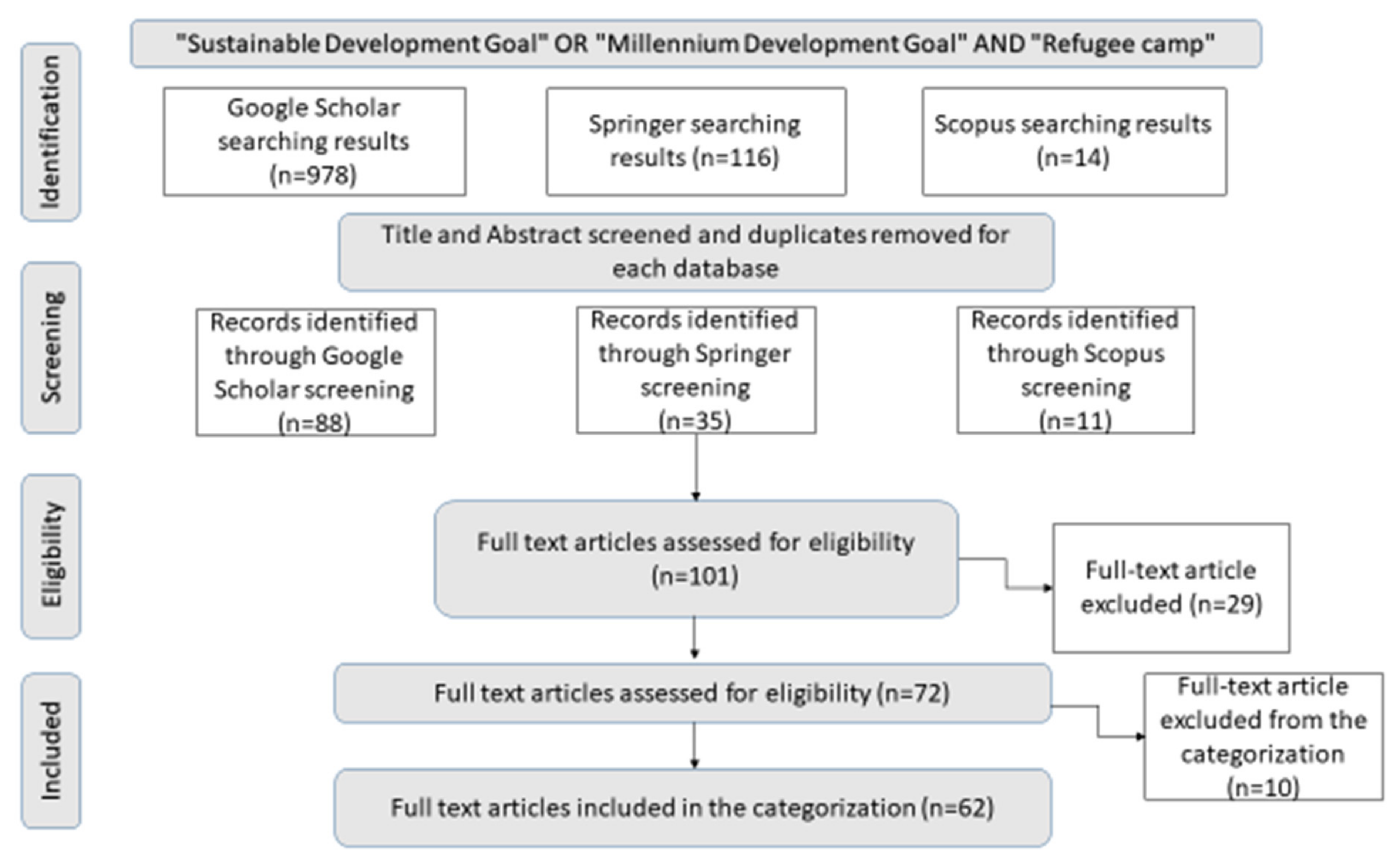

2.2. Search Strategy and Eligibility

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results and Discussion

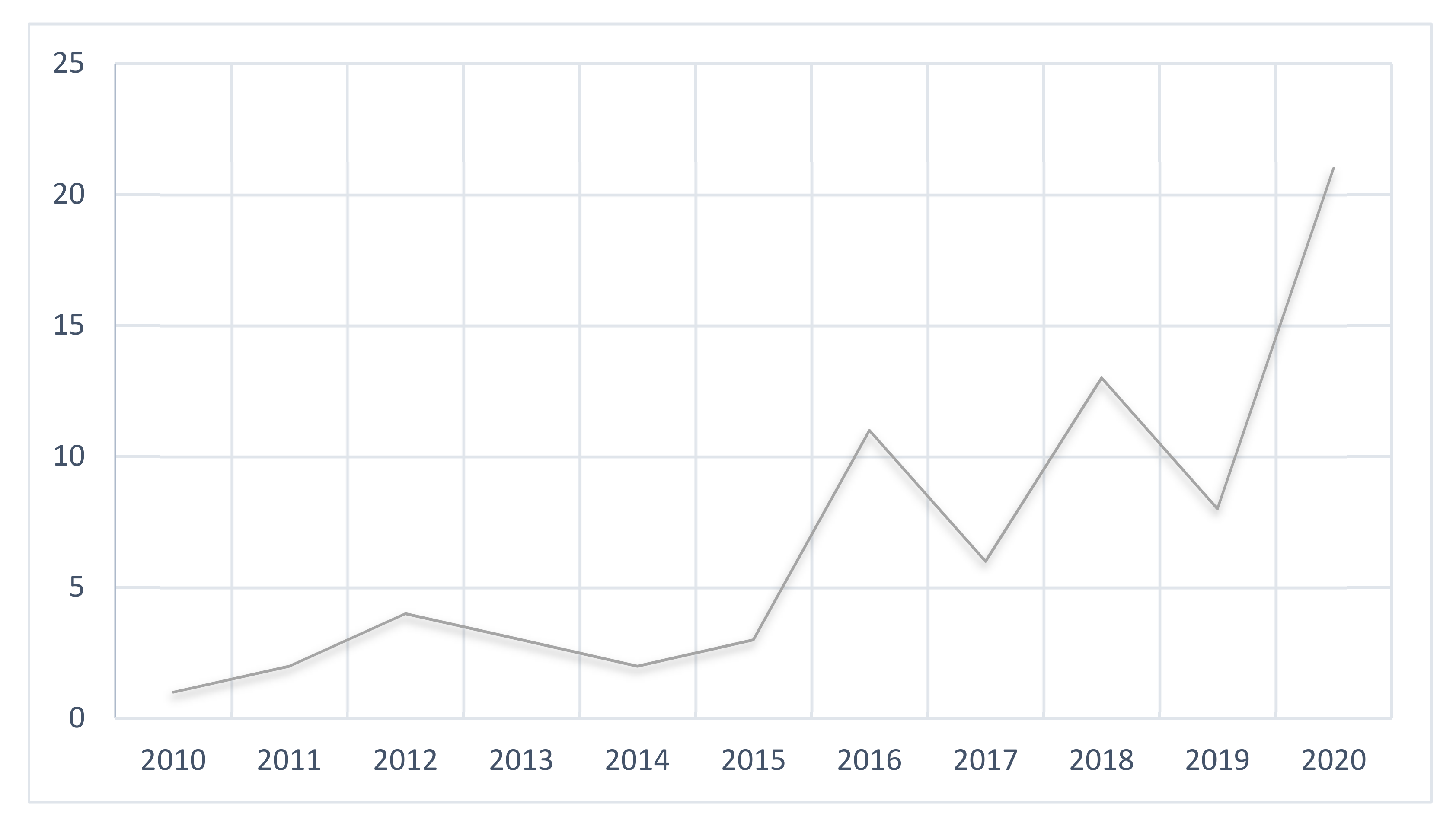

3.1. Search Results and Publication Characteristics

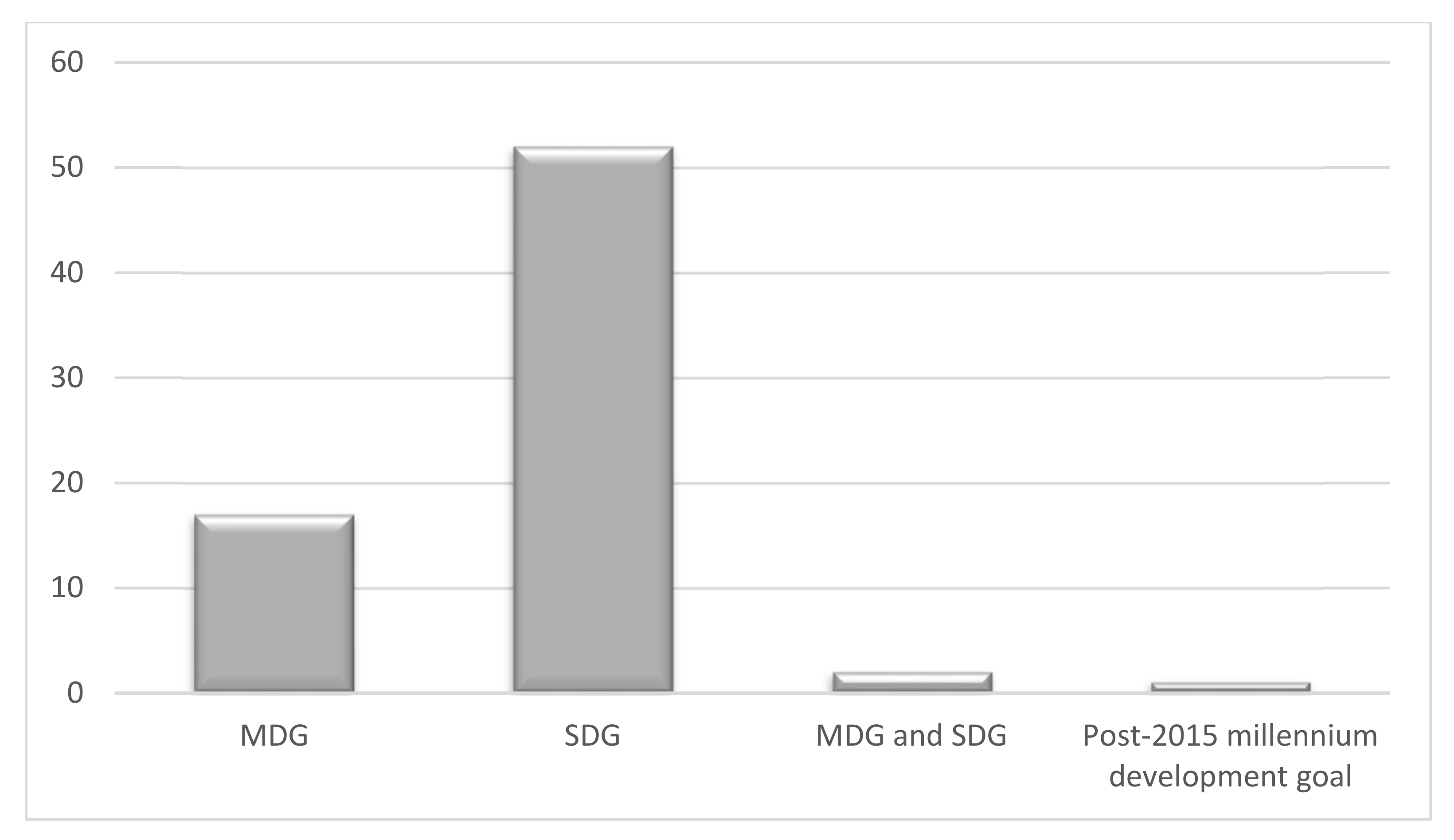

3.2. Publication Categorization

3.2.1. Planning, Development and Shelters

3.2.2. Health and Well-Being

3.2.3. Education

3.2.4. Water and Sanitation

3.2.5. Energy

3.2.6. Work and Economic Growth

3.2.7. Others

4. Conclusions

4.1. Planning, Development and Shelters

- There is lack of research and even awareness about planning RCs, in particular, what is aligned with targets 11.2, 11.6, 11.7, 11.a, and 11.c, including:

- Transportation and green and public spaces for all, and for the most fragile population within refugees, including women and children, older persons, and people with disabilities;

- Environmental impact of RCs, including air quality and municipal waste management;

- Linking RCs to surrounding rural, pre-urban, and urban areas is important to support positive economic and social relations between refugees and their HCs, and to create a better environment for refugees to be self-reliant;

- Using both technology and local knowledge to build sustainable shelters is needed in the RCs.

- The political aspects and policies that host countries apply play the most effective role in the situation and the future of refugees. We can conclude that policies applied should be changed, where RCs should no longer be a solution for a refugee influx. RCs, in most cases, turn into permanent slums and unsafe informal settlements, which do not align with SDG11, in particular targets 11.1 and 11.2.

- When the RC is the only proposed solution, long-term vision and policies should be taken into account, and current standards and approaches to planning a RC should be restudied, where “one standard fits all” is no longer accepted. Moreover, a bottom-up approach should be applied by considering the culture, religion, and local knowledge of the area, and merging them into a policy-making environment and planning phase.

4.2. Health and Well-Being

- Research found that health and well-being in RCs was the topic most studied among all other categories. It found studies addressing targets 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, 3.7, 3.8, and 3.c. However, the targets most studied were 3.1 and 3.7, which are related to maternal mortality and sexual and reproductive health-care.

- No studies were found related to targets 3.5, 3.6, and 3.9. Nevertheless, narcotic drug abuse, deaths, and injuries from road traffic accidents (due to the low quality of road and lack of lights), and deaths and illnesses from water pollution can be found in the camp environment.

- Policy applied by the host country and language barrier was the most reported obstacles that affect the access of refugees to health. Host governments and health care providers should apply policies that can be met with finance to ensure that the right method is adopted towards achieving SDG3.

- Training refugees to become skilled health workers is shown to be successful and has good results in a camp environment where there is a lack of skilled health workers; in addition, it helps reduce the language barrier.

4.3. Education

- The education section was the second reported among all categories, and studies found it covered all targets of SDG4. Studies in this review presented many case examples that were applied in camp setting; these studies can be the foundation to develop better educational interventions in RC.

- Studies showed how education plays a key role of empowering refuges, especially women, and help reduce gender inequality and achieve SDG5, SDG8, and SDG16.

- Promoting refugee-led programs, volunteering, innovation, and technology to meet the need of education in refugee communities help empower marginalized refugees, especially women, and achieve SDG4 and connected SDGs.

- Policy applied by the host country plays a key role in empowering refugees to continue their education in general and higher education in particular, where it is considered the worst in RC when compared to other education stages. At the same time, higher education is crucial to help refugees be self-reliant to build their future and their countries in the postconflict phase.

- Language barrier affects the education process, so having translators and facilitators from within the refugee community can help overcome this challenge and provide better-quality education for refugees through different partners and cooperation.

4.4. Water and Sanitation

- Studies showed how education plays a key role of empowering refuges, especially women, and helps reduce gender inequality and achieve SDG5, SDG8, and SDG16.

- More robust research and innovation solutions are needed under this category to achieve SDG6.

- Water and sanitation is one of the most significant requirements that affect the quality of life of refugees and the achievement of other SDGs, most importantly SDG3, SDG4, and SDG5.

- Innovative, low-cost, and culturally appropriate solutions can be applied to meet refugees’ need to access to safe drinking water and sanitation, and hygiene, especially for women and girls, which aligned with target 6.1, 6.2, 6.3, and 6a.

- Policies applied in the host country, cooperation, and partnership are vital to achieving SDG6.

- Availability of updated data is fundamental to the success of any intervention related to water and sanitation, and SDG6 as a whole.

4.5. Energy

- The included studies covered all targets of SDG7 and presented different interventions and partnerships that were done in different locations, including cooking fuel, clean cooking stoves, energy to generate electricity for lights, and other purposes.

- Humanitarian aid should consider access to sustainable energy an essential and official component. Access to energy is generally ignored in humanitarian settings. Nevertheless, this issue is becoming more recognized by international interventions and cooperation in the last few years.

- Using clean and sustainable energy for humanitarian aid can help reduce the cost after a number of years. Moreover, it will help improve the quality of life of refugees, conserve the environment, and reduce gender inequalities.

- Cook energy is essential to end hunger and achieve SDG2.

- Partnership between international policy frameworks, humanitarian organizations, and host governments play a key role in achieving SDG7 in humanitarian settings.

- Culture and local practice and knowledge should be taken into account when presenting a new technology or type of energy. However, promoting sustainable and modern energy within refugees and educating them on using them will help overcome the obstacles that may appear when introducing new energy practice.

- Providing energy in RC generates enterprises, job opportunities, and help achieving SDG8.

4.6. Work and Economic Growth

- There is lack of studies that address the issue of refugees’ access to decent work in a RC in the host country. More efforts are required to address SDG8 and in particular target 8.8.

- Policies applied by the host government play the most important role in improving the living conditions of refugees and achieving SDG8.

- Refugees should have basic rights, including the right to work.

- Inequitable laws and practices applied by the host government can backfire. Therefore, the host government should assist refugees to access formal employment in all levels and professions.

- Refugees’ work can help them improve their living conditions and transfer them from receiving aid to generating income, which can help improve the economic growth of their HC and generate more job opportunities.

4.7. Others

- More research regarding SDG16 and its targets should be done, including using innovation and developing technology to help ensure data protection in humanitarian settings.

- Policies applied by the host government play a key role in achieving SDG16 and, in particular, targets 16.9 and 16.b.

- More research on governance in RCs in line with SDG16 and targets 16.6 and 16.7, in particular, is required. Governance seems to be forgotten in RCs and more efforts are needed to engage refugees in the decision-making process at all levels.

- More research about partnership to achieve SDGs is required to better understand the framework of working together and encouraging international community, governments, different institutions, and NGOs at all levels to cooperate together to achieve the SDGs.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No | Author(s) [Citation No.] | Names of Author(s) | Year | Title of the Article |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Earle [17] | Lucy Earle | 2016 | Urban crises and the new urban agenda |

| 2 | Jahre et al. [18] | Marianne Jahre, Joakim Kembro, Anicet Adjahossou, and Nezih Altay | 2018 | Approaches to the design of refugee camps: An empirical study in Kenya, Ethiopia, Greece, and Turkey |

| 3 | Youssef and Mefleh [20] | Maged Youssef and Farah Mefleh | 2019 | Towards a creative sustainable promenade in informal souk architecture case study: Mar Eli as camps, in Beirut, Lebanon |

| 4 | Rush et al. [19] | David Rush, Greg Bankoff, Sarah-Jane Cooper-Knock, Lesley Gibson, Laura Hirst, Steve Jordan, Graham Spinardi, John Twigg, and Richard Shaun Walls | 2020 | Fire risk reduction on the margins of an urbanizing world |

| 5 | Howard et al. [63] | Natasha Howard, Aniek Woodward, Yaya Souare, Sarah Kollie, David Blankhart, Anna von Roenne, and Matthias Borchert | 2011 | Reproductive health for refugees by refugees in Guinea III: maternal health |

| 6 | McGready et al. [8] | Rose McGready, Machteld Boel, Marcus J. Rijken, Elizabeth A. Ashley, Thein Cho, Oh Moo, Moo Koh Paw, Mupawjay Pimanpanarak, Lily Hkirijareon, Verena I. Carrara, Khin Maung Lwin, Aung Pyae Phyo, Claudia Turner, Cindy S. Chu, Michele van Vugt, Richard N. Price, Christine Luxemburger, Feiko O. ter Kuile, Saw Oo Tan, Stephane Proux, Pratap Singhasivanon, Nicholas J. White, and François H. Nosten | 2012 | Effect of early detection and treatment on malaria related maternal mortality on the north-western border of Thailand 1986–2010 |

| 7 | Hynes et al. [15] | Michelle Hynes, Ouahiba Sakani, Paul Spiegel, and Nadine Cornier | 2012 | A Study of refugee maternal mortality in 10 countries, 2008–2010 |

| 8 | Garcia and Gostin [64] | Kelli K. Garcia and Lawrence O. Gostin | 2012 | One health, One world—The intersecting legal regimes of trade, climate change, food security, humanitarian crises, and migration |

| 9 | Urdal and Che [12] | Henrik Urdal and Chi Primus Che | 2013 | War and gender inequalities in health: The impact of armed conflict on fertility and maternal mortality |

| 10 | Turner, Turner, et al. [26] | Claudia Turner, Paul Turner, Verena Carrara, Kathy Burgoine, Saw Tha Ler Htoo, Wanitda Watthanaworawit, Nicholas P. Day, Nicholas J. White, David Goldblatt, and François Nosten | 2013 | High aates of pneumonia in children under two years of age in a south east Asian refugee population |

| 11 | Turner, Carrara, et al. [25] | Claudia Turner, Verena Carrara, Naw Aye Mya Thein, Naw Chit Mo Mo Win, Paul Turner, Germana Bancone, Nicholas J. White, Rose McGready, and François Nosten | 2013 | Neonatal intensive care in a Karen refugee camp: A four year descriptive study |

| 12 | Parr et al. [27] | Megan Parr, Colley Paw Dabu, Nan San Wai, Paw Si Say, Ma Ner, Nay Win Tun, Aye Min, Mary Ellen Gilder, François H Nosten, and Rose McGready | 2014 | Clinical audit to enhance safe practice of skilled birth attendants for the fetus with nuchal cord: Evidence from a refugee and migrant cohort |

| 13 | Bell et al. [65] | Sue Anne Bell, Jody Lori, Richard Redman, and Julia Seng | 2015 | Understanding the Effects of mental health on reproductive health service use: A mixed methods approach |

| 14 | White et al. [28] | Adrienne Lynne White, Thaw Htwe Min, Mechthild M Gross, Ladda Kajeechiwa, May Myo Thwin, Borimas Hanboonkunupakarn, Hla Hla Than, Thet Wai Zin, Marcus J Rijken, Gabie Hoogenboom, and Rose McGready | 2016 | Accelerated training of skilled birth attendants in a marginalized population on the Thai–Myanmar border: A multiple methods program evaluation |

| 15 | Chelwa, Likwa and Banda [66] | Nachela Malisenti Chelwa, Rosemary Ndonyo Likwa, and Jeremiah Banda | 2016 | Under-five mortality among displaced populations in Meheba refugee camp, Zambia, 2008–2014 |

| 16 | Khatoon et al. [67] | Salina Khatoon, Shyam Sundar Budhathoki, Kiran Bam, Rajshree Thapa, Lokesh P. Bhatt, Bidhya Basnet, and Nilambar Jha | 2018 | Socio-demographic characteristics and the utilization of HIV testing and counselling services among the key populations at the Bhutanese refugees camps in eastern Nepal |

| 17 | Parker et al. [24] | Amber L. Parker, Daniel M. Parker, Blooming Night Zan, Aung Myat Min, Mary Ellen Gilder, Maxime Ringringulu, Elsi Win, Jacher Wiladphaingern, Prakaykaew Charunwatthana, François Nosten, Sue J. Lee, and Rose McGready | 2018 | Trends and birth outcomes in adolescent refugees and migrants on the Thailand–Myanmar border, 1986–2016: An observational study |

| 18 | Paromita et al. [68] | Progga Paromita, Cinderella Akbar Mayaboti, Md. Abdul Halim, and Animesh Biswas | 2019 | Reproductive age mortality study (RAMOS) for capturing underreporting maternal mortality: Why is important in the Rohingya refugee camps, Bangladesh? |

| 19 | Saleeb [13] | Christine Saleeb | 2020 | Challenges and recommendations to reducing burden of diphtheria in refugee camps |

| 20 | Mwenyango [69] | Hadijah Mwenyango | 2020 | The place of social work in improving access to health services among refugees: A case study of Nakivale settlement, Uganda |

| 21 | Ganle et al. [70] | John Kuumuori Ganle, Doris Amoako, Leonard Baatiema, and Muslim Ibrahim | 2019 | Risky sexual behaviour and contraceptive use in contexts of displacement: Insights from a cross-sectional survey of female adolescent refugees in Ghana |

| 22 | Salisbury et al. [10] | Patricia Salisbury, Layla Hall, Sibylla Kulkus, Moo Kho Paw, Nay Win Tun, Aung Myat Min, Kesinee Chotivanich, Somjet Srikanok, Pranee Ontuwong, Supachai Sirinonthachai, François Nosten, Shawn Somerset, and Rose McGready | 2016 | Family planning knowledge, attitudes and practices in refugee and migrant pregnant and post-partum women on the Thailand–Myanmar border—a mixed methods study |

| 23 | Asnong et al. [23] | Carine Asnong, Gracia Fellmeth, Emma Plugge, Nan San Wai, Mupawjay Pimanpanarak, Moo Kho Paw, Prakaykaew Charunwatthana, François Nosten, and Rose McGready | 2018 | Adolescents’ perceptions and experiences of pregnancy in refugee and migrant communities on the Thailand-Myanmar border: A qualitative study |

| 24 | Fellmeth et al. [22] | Gracia Fellmeth, Emma Plugge, Moo Kho Paw, Prakaykaew Charunwatthana, François Nosten, and Rose McGready | 2015 | Pregnant migrant and refugee women’sperceptions of mental illness on the Thai–Myanmar border: A qualitative study |

| 25 | Adorjan et al. [6] | K. Adorjan, S. Mulugeta, M. Odenwald, DM Ndetei, AH Osman, M. Hautzinger, S. Wolf, M. Othman, JI Kizilhan, O. Pogarell, and TG Schulze | 2017 | Psychiatrische versorgung von flüchtlingen in Afrika und dem Nahen Osten (translation: Psychiatric care for refugees in Africa and the Middle East) |

| 26 | Bellos et al. [11] | Anna Bellos, Kim Mulholland, Katherine L O’Brien, Shamim A Qazi, Michelle Gayer, and Francesco Checchi | 2010 | The burden of acute respiratory infections in crisis-affected populations: A systematic review |

| 27 | (Bierhoff et al. [21] | M. Bierhoff, M. J. Rijken, W. Yotyingaphiram, M. Pimanpanarak, M. van Vugt, C. Angkurawaranon, F. Nosten, S. Ehrhardt, C. L. Thio, and R. McGready | 2020 | Tenofovir for prevention of mother to child transmission of hepatitis B in migrant women in a resource-limited setting on the Thailand–Myanmar border: A commentary on challenges of implementation |

| 28 | Schaaf et al. [71] | Marta Schaaf, Victoria Boydell, Mallory C. Sheff1, Christina Kay, Fatemeh Torabi, and Rajat Khosla | 2020 | Accountability strategies for sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights in humanitarian settings: A scoping review |

| 29 | Balhara et al. [7] | Kamna S. Balhara, David M. Silvestri, W. Tyler Winders, Anand Selvam, Sean M. Kivlehan, Torben K. Becker, and Adam C. Levine, Global Emergency Medicine Literature Review Group (GEMLR) | 2017 | Impact of nutrition interventions on pediatric mortality and nutrition outcomes in humanitarian emergencies: A systematic review |

| 30 | Khan and DeYoung [14] | Aishah Khan and Sarah E. DeYoung | 2018 | Maternal health services for refugee populations: Exploration of best practices |

| 31 | Meyer et al. [38] | Sarah R Meyer, Gary Yu, Sabrina Hermosilla, and Lindsay Stark | 2018 | School violence, perceptions of safety and school attendance: Results from a cross-sectional study in Rwanda and Uganda |

| 32 | Osman and Bin Ahmad Dahlan [46] | Gamal Mohamed Osman and Abdul Rahman Bin Ahmad Dahlan | 2019 | Empowering Eritrean refugees in Sudan through quality education for sustainable development |

| 33 | Katsigianni and Kaila [39] | Victoria Katsigianni and Maria Kaila | 2019 | Refugee education in Greece: A case study in primary school |

| 34 | Laxton et al. [35] | Debra Laxton, Linda Cooper, Purna Shrestha, and Sarah Younie | 2020 | Translational research to support early childhood education in crisis settings: A case study of collaborative working with Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar |

| 35 | Plessia [42] | Vasiliki Plessia | 2020 | “Fallen angels” under European Union’s migration gesture |

| 36 | Yeo, Gagnon and Thako [43] | Subin Sarah Yeo, Terese Gagnon, and Hayso Thako | 2020 | Schooling for a atateless nation: The predicament of education without consensus for karen refugees on the Thailand–Myanmar border |

| 37 | Gallagher and Bauer [45] | Matthew Gallagher and Carrie Bauer | 2020 | Refugee higher education and future reconstruction efforts: exploring the connection through the innovative technological implementation of a university course in Nakivale refugee settlement, Uganda |

| 38 | Santo and Scott [36] | A Di Santo and KJ Scott | 2020 | A child’s right to early childhood education in emergency contexts |

| 39 | Piper et al. [41] | Benjamin Piper, Sarah Dryden-Peterson, Vidur Chopra, Celia Reddick, and Arbogast Oyanga | 2020 | Are refugee children learning? early grade literacy in a refugee camp in Kenya |

| 40 | Walton et al. [32] | Elizabeth Walton, Joanna McIntyre, Salome Joy Awidi, Nicole De Wet-Billings, Kerryn Dixon, Roda Madziva, David Monk, Chamunogwa Nyoni, Juliet Thondhlana, and Volker Wedekind | 2020 | Compounded exclusion: Education for disabled refugees in Sub-Saharan Africa |

| 41 | O’keeffe [44] | O’keeffe, P. | 2020 | The case for engaging online tutors for supporting learners in higher education in refugee contexts |

| 42 | Akua-Sakyiwah [40] | Beatrice Akua-Sakyiwah | 2020 | Intersecting social structures and humanactors: Ganfoso refugees’ settling experiences and impact on children’s education |

| 43 | Irfan [37] | Anne Irfan | 2016 | The loss of education: Palestinian refugees from Syria and UN SDG4 |

| 44 | Jabbar and Zaza [47] | Sinaria Abdel Jabbara and Haidar Ibrahim Zazab | 2016 | Evaluating a vocational training programme for women refugees at the Zaatari camp in Jordan: women empowerment: a journey and not an output |

| 45 | Obodoruku [34] | Benedicta Obodoruku | 2019 | Syrian refugees and paucity of information |

| 46 | Fatoni and Stewart [50] | Zainal Fatoni, and Donald E. Stewart | 2012 | Sanitation in an emergency situation:A case study of the eruption of Mt Merapi, Indonesia, 2010 |

| 47 | Faure, Faustand and Kaminsky [48] | Julie C. Faure, Kasey M. Faustand, and Jessica Kaminsky | 2019 | Legitimization of the inclusion of cultural practicesin the planning of water and sanitation services for displaced persons |

| 48 | Ajibade and Tota-Maharaj [16] | Oluwatoyin Opeyemi Ajibade, and Kiran Tota-Maharaj | 2018 | Comparative study of sustainable drainage systems for refugee camps stormwater management |

| 49 | Abebe et al. [49] | Lydia Abebe, Andrew J. Karon, Andrew J. Koltun, Ryan D. Cronk, Robert E. S. Bain, and Jamie Bartram | 2018 | Microbial contamination of non-household drinking water sources: a systematic review |

| 50 | Khoday and Gitonga [51] | Kishan Khoday and Stephen Gitonga | 2015 | Solar aid |

| 51 | Lehne et al. [52] | Johanna Lehne, William Blyth, Glada Lahn, Morgan Bazilian, and Owen Grafham | 2016 | Energy services for refugees and displaced people |

| 52 | Caniato, Carliez and Thulstrup [53] | Marco Caniatoa, Daphné Carliezb, and Andreas Thulstrup | 2017 | Challenges and opportunities of new energy schemes for food security in humanitarian contexts: A selective review |

| 53 | Benka-Coker et al. [54] | Megan L. Benka-Cokera, Wubshet Tadeleb, Alex Milanoc, Desalegn Getanehb, and Harry Stokes | 2018 | A case study of the ethanol clean cook stove intervention and potentialscale-up in Ethiopia |

| 54 | Miller and Ulfstjerne [55] | Rachel L. Miller and Michael A. Ulfstjerne | 2020 | Trees, tensions, and transactional communities: Problematizing frameworksfor energy poverty alleviation in the Rhino camp refugee settlement, Uganda |

| 55 | Pearl-Martinez [56] | Rebecca Pearl-Martinez | 2020 | Global trends impacting gender equality in energy access |

| 56 | Muhammad [58] | Rehan Khan Muhammad | 2011 | International forced migration and Pak-Afghan development concerns: exploring Afghan refugee livelihood trategies |

| 57 | Schön et al. [33] | Anna Schön, Shahad Al-Saadi, Jakob Grubmüller, and Dorit Schumann-Bölsche | 2018 | Developing a camp performance indicator system and its application to Zaatari, Jordan |

| 58 | Naoum [57] | Diana Naoum | 2016 | Poverty and unemployment: Palestinian refugees in Lebanon and the sustainable development goals 1 and 8 |

| 59 | Hayes [59] | Ben Hayes | 2017 | Migration and data protection: Doing no harm in an age of mass displacement mass surveillance and “big data” |

| 60 | Brinham [60] | Natalie Brinham | 2019 | Looking beyond invisibility: Rohingyas’ dangerous encounters with papers and cards |

| 61 | Moreno-Serna et al. [62] | Jaime Moreno-Serna, Teresa Sánchez-Chaparro, Javier Mazorra, Ander Arzamendi, Leda Stott, and Carlos Mataix | 2020 | Transformational collaboration for the SDGs: The alianza shire’s work to provide energy access in refugee camps and host communities |

| 62 | Cheesman [61] | Margie Cheesman | 2020 | Self-sovereignty for refugees? The contested horizons of digital identity |

| 63 | Nasser, Maclachlan and McVeigh [72] | Khaled Nasser, Malcolm MacLachlan, and Joanne McVeigh | 2016 | Social inclusion and mental health of children with physical disabilities in Gaza, Palestine |

| 64 | Thielemans et al. [9] | L. Thielemans, M. Trip-Hoving, J.Landier, C.Turner, T.J.Prins, E.M.N.Wouda, B.Hanboonkunupakarn, C. Po, C.Beau, M.Mu, T.Hannay, F. Nosten, B. Van Overmeire, R. McGready, and V. I. Carrara | 2018 | Indirect neonatal hyperbilirubinemia inhospitalized neonates on the Thai-Myanmar border: A review of neonatalmedical records from 2009 to 2014 |

| 65 | Mastor et al. [73] | Roxana A. Mastor, Michael H. Dworkin, Mackenzie L. Landa, and Emily Duff | 2018 | Energy justice and climate-refugees |

| 66 | Shackelford et al. [74] | Brandie Banner Shackelford, Ryan Cronk, Nikki Behnke, Brittany Cooper, Raymond Tu, Mabel D’Souzaa, Jamie Bartram, Ryan Schweitzer, and Dilshad Jaff | 2020 | Environmental health in forced displacement: A systematic scoping review of the emergency phase |

| 67 | Nielsen [75] | Nielsen, B.F. | 2014 | Imperatives and trade-offs for the humanitarian designer: Off-grid energy for humanitarian relief |

| 68 | Fetters et al. [76] | Tamara Fetters, Sayed Rubayet, Sharmin Sultana, Shamila Nahar, Shadie Tofigh, Lea Jones, Ghazaleh Samandari, and Bill Powell | 2020 | Navigating the crisis landscape: engagingthe ministry of health and United Nations agencies to make abortion care available to Rohingya refugees |

| 69 | Sami et al. [77] | Samira Sami, Kate Kerber, Solomon Kenyi, Ribka Amsalu, Barbara Tomczyk, Debra Jackson, Alexander Dimiti, Elaine Scudder, Janet Meyers, Jean Paul De Charles Umurungi, Kemish Kenneth, and Luke C Mullany | 2017 | State of newborn care in South Sudan’s displacement camps: A descriptive study of facility-based deliveries |

| 70 | Sami et al. [78] | Samira Sami, Ribka Amsalu, Alexander Dimiti, Debra Jackson, Solomon Kenyi, Janet Meyers, Luke C. Mullany, Elaine Scudder, Barbara Tomczyk, and Kate Kerber | 2018 | Understanding health systems to improve community and facility level newborn care among displaced populations in South Sudan: a mixed methods case study |

| 71 | Khanfar, Al-Faqheri and Al-Halhouli [79] | Mohammad F. Khanfar, Wisam Al-Faqheri, and Ala’aldeen Al-Halhouli | 2017 | Low cost lab on chip for the colorimetric detection of nitrate in mineral water products |

| 72 | Presler-Marshall, Jones and Odeh [80] | Elizabeth Presler-Marshall, Nicola Jones, and Kifah Bani Odeh | 2020 | ”Even though I am blind, I am still human!”: The neglect of adolescents with disabilities’ human rights in conflict-affected contexts |

Appendix B

| No. | Author(s) [Citation No.] | Title | Mentioned in Text SDG/MDG | Target/Topic Related to Health/ | SDG3 Is Linked to |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | McGready et al. [8] | Effect of early detection and treatment on malaria related maternal mortality on the north-western border of Thailand 1986–2010 | MDG5 MDG6 | 3.1/Malaria Related maternal mortality | SDG2 SDG4 |

| 2 | Hynes et al. [15] | A study of refugee maternal mortality in 10 countries, 2008–2010 | MDG5 | 3.1/Maternal mortality | SDG1 SDG4 |

| 3 | Howard et al. [63] | Reproductive health for refugees by refugees in Guinea III: Maternal health | MDG5 | 3.1/Reproductive health: maternal mortality | SDG1 SDG4 SDG5 SDG8 SDG16 |

| 4 | Garcia and Gostin [64] | One health, one world—The intersecting legal regimes of trade, climate change, food security, humanitarian crises, and migration | MDG1 | 3.8/Health (general) and international law | MDG1 SDG1 SDG2 SDG6 SDG9 SDG10 SDG11SDG13SDG15 SDG16SDG17 |

| 5 | Urdal and Che [12] | War and gender inequalities in health: The impact of armed conflict on fertility and maternal mortality | MDG5 | 3.1/Fertility and maternal mortality | SDG1 SDG2 SDG4 SDG5 SDG6 SDG7 |

| 6 | Turner, Turner, et al. [26] | High rates of pneumonia in children under two years of age in a south east Asian refugee population | MDG4 | 3.2/Pneumonia in children under two years of age | SDG7 SDG11 |

| 7 | Turner, Carrara, et al. [25] | Neonatal intensive care in a Karen refugee camp: A 4-year descriptive study | MDG4 | 3.2/Neonatal mortality | SDG2 SDG4 SDG7 |

| 8 | Parr et al. [27] | Clinical audit to enhance safe practice of skilled birth attendants for the fetus with nuchal cord: Evidence from a refugee and migrant cohort | MDG5 | 3.1/Skilled birth attendants 3.c/Training of the health workforce | SDG4 |

| 9 | Bell et al. [65] | Understanding the effects of mental health on reproductive health service use: A mixed methods approach | MDG5 | 3.4/promote mental health and well-being 3.7/Effects of mental health on reproductive health service use | SDG1 SDG4 SDG5 SDG8 SDG13 |

| 10 | Chelwa, Likwa and Banda [66] | Under-five mortality among displaced populations in Meheba refugee camp, Zambia, 2008–2014 | MDG4 | 3.2/Under-five mortality | SDG1 SDG2 SDG4 SDG6 SDG11 |

| 11 | Bellos et al. [11] | The burden of acute respiratory infections in crisis-affected populations: A systematic review | MDG6 | 3.3/Acute respiratory infections | SDG2 SDG6 SDG7 SDG11 SDG13 |

| 12 | Balhara et al. [7] | Impact of nutrition interventions on pediatric mortality and nutrition outcomes in humanitarian emergencies: A systematic review | MDG4 | 3.2/Reducing child mortality/pediatric mortality | SDG1 SDG2 SDG4 SDG8 SDG7 SDG13 SDG15 |

| 13 | White et al. [28] | Accelerated training of skilled birth attendants in a marginalized population on the Thai–Myanmar border: A multiple methods program evaluation | SDG3 | 3.1/Skilled birth attendant 3.c. training of the health workforce | SDG4 |

| 14 | Bierhoff et al. [21] | Tenofovir for prevention of mother to child transmission of hepatitis B in migrant women in a resource-limited setting on the Thailand–Myanmar border: A commentary on challenges of implementation | SDG3 | 3.3/Tenofovir for prevention of mother to child transmission of hepatitis B | |

| 15 | Fellmeth et al. [22] | Pregnant migrant and refugee women’s perceptions of mental illness on the Thai–Myanmar border: A qualitative study | MDG3, MDG4, and MDG5 (Pregnant women and mental health) | 3.4/Mental illness in women of childbearing age, especially during pregnancy and the first-year post-partum | SDG5 SDG8 |

| 16 | Asnong et al. [23] | Adolescents’ perceptions and experiences of pregnancy in refugee and migrant communities on the Thailand–Myanmar border: A qualitative study | SDG3 | 3.7/Adolescents’ pregnancy | SDG1, SDG2, SDG3, SDG4, SDG5, SDG8, SDG10 |

| 17 | Salisbury et al. [10] | Family planning knowledge, attitudes and practices in refugee and migrant pregnant and post-partum women on the Thailand–Myanmar border—a mixed methods study | SDG3 | 3.7/Family planning | SDG1 SDG4 SDG8 |

| 18 | Parker et al. [24] | Trends and birth outcomes in adolescent refugees and migrants on the Thailand-Myanmar border, 1986–2016: An observational study | SDG3 | 3.7/Sexual and reproductive healthcare | SDG4 |

| 19 | Schaaf et al. [71] | Accountability strategies for sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights in humanitarian settings: Ascoping review | SDG3, SDG5, and SDG16 | 3.7/Accountability strategies for sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights | SDG5 SDG16 SDG17. |

| 20 | Khatoon et al. [67] | Socio-demographic characteristics and the utilization of HIV testing and counselling services among the key populations at the Bhutanese refugees camps in eastern Nepal | SDG3 | 3.3/Utilization of HIV testing and counselling services | SDG1, SDG4 |

| 21 | Paromita et al. [68] | Reproductive age mortality study (RAMOS) for capturing underreporting maternal mortality: why is important in the Rohingya refugee camps, Bangladesh? | SDG5 + SDGs (but it is related to SDG3) | 3.1/Maternal mortality | SDG1 SDG5 |

| 22 | Saleeb [13] | Challenges and recommendations to reducing burden of diphtheria in refugee camps | SDG3 | 3.3/Diphtheria | SDG4 SDG17 |

| 23 | Mwenyang [69] | The place of social work in improving access to health services among refugees: A case study of Nakivale settlement, Uganda | SDG3 | 3.8/Social work in improving access to health services | SDG1 SDG5 SDG8 SDG10 SDG16 |

| 24 | Ganle et al. [70] | Risky sexual behavior and contraceptive use in contexts of displacement: Insights from a cross-sectional survey of female adolescent refugees in Ghana | SDG3 | 3.7/Sexual and reproductive healthcare | SDG1 SDG4 SDG5 SDG10 SDG16 SGD17 |

| 25 | Khan and DeYoung [14] | Maternal health services for refugee populations: Exploration of best practices | SDG3 + SDG5 (as text) | 3.1/Maternal health services | SDG1 SDG4 SDG5 SDG17 |

| 26 | Adorjan et al. [6] | Psychiatrische versorgung von flüchtlingen in Afrika und dem Nahen Osten (translation:Psychiatric care for refugees in Africa and the Middle East) | SDG3 + SDG10 (as text) | 3.4/Mental health and well-being | SDG2 SDG4 SDG7 SDG8 SDG10 SDG17 |

References

- UNHCR. UNHCR Engagement with the Sustainable Development Goals-Updated Guidance Note. 2019. Available online: www.unhcr.org (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- UNHCR. The Sustainable Development Goals and the Global Compact on Refugees. 2020. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/5efcb5004.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- UNHCR. Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. 2010. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3be01b964.html (accessed on 13 April 2021).

- UNHCR. UNHCR Master Glossary of Terms. 2006. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/42ce7d444.html (accessed on 13 April 2021).

- Shah, A.; Jones, M.P.; Holtmann, G.J. Basics of meta-analysis. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 39, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorjan, K.; Mulugeta, S.; Odenwald, M.; Ndetei, D.M.; Osman, A.H.; Hautzinger, M.; Wolf, S.; Othman, M.; Kizilhan, J.I.; Pogarell, O.; et al. Psychiatric care of refugees in Africa and the Middle East: Challenges and solutions. Nervenarzt 2017, 88, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balhara, K.S.; Silvestri, D.M.; Tyler Winders, W.; Selvam, A.; Kivlehan, S.M.; Becker, T.K.; Levine, A.C. Impact of nutrition interventions on pediatric mortality and nutrition outcomes in humanitarian emergencies: A systematic review. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2017, 22, 1464–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGready, R.; Boel, M.; Rijken, M.J.; Ashley, E.A.; Cho, T.; Moo, O.; Paw, M.K.; Pimanpanarak, M.; Hkirijareon, L.; Carrara, V.I.; et al. Effect of early detection and treatment on malaria related maternal mortality on the north-western border of thailand 1986–2010. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thielemans, L.; Trip-Hoving, M.; Landier, J.; Turner, C.; Prins, T.J.; Wouda, E.M.N.; Hanboonkunupakarn, B.; Po, C.; Beau, C.; Mu, M.; et al. Indirect neonatal hyperbilirubinemia inhospitalized neonates on the Thai-Myanmar border—A review of neonatalmedical records from 2009 to 2014. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, P.; Hall, L.; Kulkus, S.; Paw, M.K.; Tun, N.W.; Min, A.M.; Chotivanich, K.; Srikanok, S.; Ontuwong, P.; Sirinonthachai, S.; et al. Family planning knowledge, attitudes and practices in refugee and migrant pregnant and post-partum women on the Thailand-Myanmar border—A mixed methods study. Reprod. Health 2016, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellos, A.; Mulholland, K.; O’Brien, K.L.; Qazi, S.A.; Gayer, M.; Checchi, F. The burden of acute respiratory infections incrisis-affected populations- a systematic review. Confl. Health 2010, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urdal, H.; Che, C.P. War and Gender Inequalities in Health: The Impact of Armed Conflict on Fertility and Maternal Mortality. Int. Interact. 2013, 39, 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleeb, C. Challenges and Recommendations to Reducing Burden of Diphtheria in Refugee Camps. Glob. Health Annu. Rev. 2020, 1, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; DeYoung, S.E. Maternal health services for refugee populations: Exploration of best practices. Glob. Public Health 2019, 14, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, M.; Sakani, O.; Spiegel, P.; Cornier, N. A study of refugee maternal mortality in 10 countries, 2008–2010. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2012, 38, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajibade, O.O.; Tota-Maharaj, K. Comparative study of sustainable drainage systems for refugee camps stormwater management. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Munic. Eng. 2018, 171, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, L. Urban crises and the new urban agenda. Environ. Urban. 2016, 28, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahre, M.; Kembro, J.; Adjahossou, A.; Altay, N. Approaches to the design of refugee camps: An empirical study in Kenya, Ethiopia, Greece, and Turkey. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2018, 8, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, D.; Bankoff, G.; Cooper-Knock, S.J.; Gibson, L.; Hirst, L.; Jordan, S.; Spinardi, G.; Twigg, J.; Walls, R.S. Fire risk reduction on the margins of an urbanizing world. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 29, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, M.; Mefleh, F. Towards a Creative Sustainable Promenade in Informal Souk Architecturecase Study: Mar Elias Camps, in Beirut, Lebanon. BAU J. Creat. 2019, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bierhoff, M.; Rijken, M.J.; Yotyingaphiram, W.; Pimanpanarak, M.; Van Vugt, M.; Angkurawaranon, C.; Nosten, F.; Ehrhardt, S.; Thio, C.L.; McGready, R. Tenofovir for prevention of mother to child transmission of hepatitis B in migrant women in a resource-limited setting on the Thailand-Myanmar border: A commentary on challenges of implementation. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellmeth, G.; Plugge, E.; Paw, K.M.; Charunwatthana, P.; Nosten, F.; McGready, R. Pregnant migrant and refugee women’s perceptions of mental illness on the Thai-Myanmar border: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnong, C.; Fellmeth, G.; Plugge, E.; Wai, N.S.; Pimanpanarak, M.; Paw, M.K.; Charunwatthana, P.; Nosten, F.; McGready, R. Adolescents’ perceptions and experiences of pregnancy in refugee and migrant communities on the Thailand-Myanmar border: A qualitative study. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.L.; Parker, D.M.; Zan, B.N.; Min, A.M.; Gilder, M.E.; Ringringulu, M.; Win, E.; Wiladphaingern, J.; Charunwatthana, P.; Nosten, F.; et al. Trends and birth outcomes in adolescent refugees and migrants on the Thailand-Myanmar border, 1986–2016: An observational study [version 1; referees: 2 approved]. Wellcome Open Res. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.; Carrara, V.; Thein, N.A.M.; Mo Mo Win, N.C.; Turner, P.; Bancone, G.; White, N.J.; McGready, R.; Nosten, F. Neonatal Intensive Care in a Karen Refugee Camp: A 4 Year Descriptive Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, C.; Turner, P.; Carrara, V.; Burgoine, K.; Tha Ler Htoo, S.; Watthanaworawit, W.; Day, N.P.; White, N.J.; Goldblatt, D.; Nosten, F. High Rates of Pneumonia in Children under Two Years of Age in a South East Asian Refugee Population. PLoS ONE 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, M.; Dabu, C.P.; Wai, N.S.; Say, P.S.; Ner, M.; Tun, N.W.; Min, A.; Gilder, M.E.; Nosten, F.H.; McGready, R. Clinical audit to enhance safe practice of skilled birth attendants for the fetus with nuchal cord: Evidence from a refugee and migrant cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, A.L.; Min, T.H.; Gross, M.M.; Kajeechiwa, L.; Thwin, M.M.; Hanboonkunupakarn, B.; Than, H.H.; Zin, T.W.; Rijken, M.J.; Hoogenboom, G.; et al. Accelerated Training of Skilled Birth Attendants in a Marginalized Population on theThai-Myanmar Border: A Multiple Methods Program Evaluation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals and Targets (from the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development) Indicators. 2020. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/Global Indicator Framework after 2020 review_Eng.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2021).

- UNHCR. Refugee Education 2030: A Strategy for Refugee Inclusion. 2019. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/71213 (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- UNHCR. Refugee Education in Crisis: More than Half of the World’s School-Age Refugee Children Do Not Get an Education. 2019. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/news/press/2019/8/5d67b2f47/refugee-education-crisis-half-worlds-school-age-refugee-children-education.html (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Walton, E.; McIntyre, J.; Awidi, S.J.; De Wet-Billings, N.; Dixon, K.; Madziva, R.; Monk, D.; Nyoni, C.; Thondhlana, J.; Wedekind, V. Compounded Exclusion: Education for Disabled Refugees in Sub-Saharan Africa. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, A.M.; Al-Saadi, S.; Grubmueller, J.; Schumann-Bölsche, D. Developing a camp performance indicator system and its application to Zaatari, Jordan. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2018, 8, 346–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obodoruku, B. Syrian Refugees and Paucity of Information. Inf. Needs Refug. Sustain. Dev. Goals 2019, 23, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Laxton, D.; Cooper, L.; Shrestha, P.; Younie, S. Translational research to support early childhood education in crisis settings: A case study of collaborative working with Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar. Education 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Santo, A.; Scott, K.-J. A Child’s Right to Early Childhood Education in Emergency Contexts. Can. J. Child. Rights 2020, 7, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, A. The Loss of education: Palestinian refugees from Syria and UN SDG 4. J. Palest. Refug. Stud. 2016, 6, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.R.; Yu, G.; Hermosilla, S.; Stark, L. School violence, perceptions of safety and school attendance: Results from a cross-sectional study in Rwanda and Uganda. J. Glob. Health Rep. 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsigianni, V.; Kaila, M. Refugee Education in Greece: A Case Study in Primary School. IJAEDU Int. E J. Adv. Educ. 2019, 5, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Akua-Sakyiwah, B. Intersecting social structures and humanactors- Ganfoso refugees’settlingexperiences and impact on children’seducation.pdf. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2020, 43, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Piper, B.; Dryden-Peterson, S.; Chopra, V.; Reddick, C.; Oyanga, A. Are Refugee Children Learning? Early Grade Literacy in a Refugee Camp in Kenya. J. Educ. Emergencies 2020, 5, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plessia, V. “Fallen Angels” under European Union’s migration gesture. HAPSc Policy Briefs Ser. 2020, 1, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, S.S.; Gagnon, T.; Thako, H. Schooling for a stateless nation: The predicament of education without consensus for Karen refugees on the Thailand-Myanmar border. Asian J. Peacebuild. 2020, 8, 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’keeffe, P. The case for engaging online tutors for supporting learners in higher education in refugee contexts. Res. Learn. Technol. 2020, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M.; Bauer, C. Refugee Higher Education and Future Reconstruction Efforts: Exploring the Connection through the Innovative Technological Implementation of a University Course in Nakivale Refugee Settlement, Uganda. Curr. Issues Comp. Educ. 2020, 22, 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, G.M.; Bin Ahmad Dahlan, A.R. Empowering Eritrean refugees in Sudan through Quality Education for sustainable development. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Res. 2019, 7, 476–483. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbar, S.A.; Zaza, H.I. Evaluating a vocational training programme for women refugees at the Zaatari camp in Jordan: Women empowerment: A journey and not an output. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2016, 21, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, J.C.; Faustand, K.M.; Kaminsky, J. Legitimization of the Inclusion of Cultural Practicesin the Planning of Water and Sanitation Services for Displaced Persons. Water 2019, 11, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, L.; Karon, A.J.; Koltun, A.J.; Cronk, R.D.; Bain, R.E.S.; Bartram, J. Microbial contamination of non-household drinking water sources: A systematic review. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2018, 8, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoni, Z.; Stewart, D.E. Sanitation in An Emergency Situation: A Case Study of The Eruption of Mount Merapi, Indonesia, 2010. Int. J. Environ. Prot. 2012, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Khoday, K.; Gitonga, S. Solar aid. Oxf. Energy Forum 2015, 102, 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lehne, J.; Blyth, W.; Lahn, G.; Bazilian, M.; Grafham, O. Energy services for refugees and displaced people. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2016, 13–14, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniato, M.; Carliez, D.; Thulstrup, A. Challenges and opportunities of new energy schemes for food security in humanitarian contexts: A selective review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2017, 22, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benka-Coker, M.L.; Tadele, W.; Milano, A.; Getaneh, D.; Stokes, H. A case study of the ethanol CleanCook stove intervention and potential scale-up in Ethiopia. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2018, 46, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.L.; Ulfstjerne, M.A. Trees, tensions, and transactional communities: Problematizing frameworks for energy poverty alleviation in the Rhino Camp refugee settlement, Uganda. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl-Martinez, R. Global Trends Impacting Gender Equality in Energy Access. IDS Bull. 2020, 51, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoum, D. Poverty and Unemployment: Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon and the Sustainable Development Goals 1 and 8. J. Palest. Refug. Stud. 2016, 6, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, R.K. International Forced Migration and Pak- Afghan Development Concerns: Exploring Afghan Refugee Livelihood Strategies. J. Soc. Dev. Sci. 2011, 2, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, B. Migration and data protection: Doing no harm in an age of mass displacement, mass surveillance and “big data”. Int. Rev. Red Cross 2017, 99, 179–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinham, N. Looking beyond invisibility: Rohingyas’ dangerous encounters with papers and cards. Tilbg. Law Rev. 2019, 24, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheesman, M. Self-Sovereignty for Refugees-The Contested Horizons of Digital Identity.pdf. Geopolitics 2020, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Serna, J.; Sánchez-Chaparro, T.; Mazorra, J.; Arzamendi, A.; Stott, L.; Mataix, C. Transformational collaboration for the SDGs: The alianza shire’s work to provide energy access in refugee camps and host communities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, N.; Woodward, A.; Souare, Y.; Kollie, S.; Blankhart, D.; Von Roenne, A.; Borchert, M. Reproductive health for refugees by refugees in Guinea III- maternal health. Confl. Health 2011, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, K.K.; Gostin, L.O. One Health, One World—The Intersecting Legal Regimes of Trade, Climate Change, Food Security, Humanitarian Crises, and Migration. Laws 2012, 1, 4–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.A.; Lori, J.; Redman, R.; Seng, J. Understanding the Effects of Mental Health on Reproductive Health Service Use: A Mixed Methods Approach. Health Care Women Int. 2016, 37, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelwa, N.M.; Likwa, R.N.; Banda, J. Under-five mortality among displaced populations in Meheba refugee camp, Zambia, 2008–2014. Arch. Public Health 2016, 74, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Khatoon, S.; Budhathoki, S.S.; Bam, K.; Thapa, R.; Bhatt, L.P.; Basnet, B.; Jha, N. Socio-demographic characteristics and the utilization of HIV testing and counselling services among the key populations at the Bhutanese Refugees Camps in Eastern Nepal. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Paromita, P.; Mayaboti, C.A.; Halim, A.M.; Biswas, A. Reproductive age mortality study (RAMOS) for capturing underreporting maternal mortality: Why is it important in the Rohingya refugee camps, Bangladesh? Int. J. Percept. Public Health 2019, 3, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwenyango, H. The place of social work in improving access to health services among refugees: A case study of Nakivale settlement, Uganda. Int. Soc. Work 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganle, J.K.; Amoako, D.; Baatiema, L.; Ibrahim, M. Risky sexual behaviour and contraceptiveuse in contexts of displacement- insightsfrom a cross-sectional survey of femaleadolescent refugees in Ghana. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 127, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf, M.; Boydell, V.; Sheff, M.C.; Kay, C.; Torabi, F.; Khosla, R. Accountability strategies for sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights in humanitarian settings: A scoping review. Confl. Health 2020, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasser, K.; Maclachlan, M.; McVeigh, J. Social inclusion and mental health of children with physical disabilities in gaza, Palestine. Disabil. CBR Incl. Dev. 2016, 27, 5–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastor, R.; Dworkin, M.; Landa, M.; Duff, E. Energy Justice and Climate-Refugees. Energy Law J. 2018, 39, 139. [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford, B.B.; Cronk, R.; Behnke, N.; Cooper, B.; Tu, R.; D’Souzaa, M.; Bartram, J.; Schweitzer, R.; Jaff, D. Environmental health in forced displacement: A systematic scoping review of the emergency phase. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 714, 136553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, B.F. Imperatives and trade-offs for the humanitarian designer: Off-grid energy for humanitarian relief. J. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 7, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, T.; Rubayet, S.; Sultana, S.; Nahar, S.; Tofigh, S.; Jones, L.; Samandari, G.; Powell, B. Navigating the crisis landscape: Engaging the ministry of health and United Nations agencies to make abortion care available to Rohingya refugees. Confl. Health 2020, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sami, S.; Kerber, K.; Kenyi, S.; Amsalu, R.; Tomczyk, B.; Jackson, D.; Dimiti, A.; Scudder, E.; Meyers, J.; Umurungi, J.P.D.C.; et al. State of newborn care in South Sudan’s displacement camps: A descriptive study of facility-based deliveries. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sami, S.; Amsalu, R.; Dimiti, A.; Jackson, D.; Kenyi, S.; Meyers, J.; Mullany, L.C.; Scudder, E.; Tomczyk, B.; Kerber, K. Understanding health systems to improve community and facility level newborn care among displaced populations in South Sudan: A mixed methods case study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanfar, M.F.; Al-Faqheri, W.; Al-Halhouli, A. Low cost lab on chip for the colorimetric detection of nitrate in mineral water products. Sensors 2017, 17, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presler-Marshall, E.; Jones, N.; Odeh, K.B. ‘Even though I Am Blind, I Am Still Human!’: The Neglect of Adolescents with Disabilities’ Human Rights in Conflict-Affected Contexts. Child Indic. Res. 2020, 13, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Exclusion Criteria | Subcriteria |

|---|---|

| Wrong study type | Not a peer-reviewed article; book chapter; documents that do not provide any conclusion or recommendation related to refugees in camp |

| Not related to SDGS | Neither SDGs nor MDGs mentioned |

| Wrong setting | Urban refugees, refugee’s community, migrant, any other sitting not related to camps |

| Full text inaccessible | - |

| The Name of the Journal | Number of Included Publications |

|---|---|

| PLoS One | 4 |

| Conflict and Health | 4 |

| Reproductive Health | 3 |

| BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth | 3 |

| Journal of Palestinian Refugee Studies | 2 |

| International Journal for Equity in Health | 2 |

| Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management | 2 |

| Article | Year | Total Number of Citations | Average Citation Per Year | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Rank | No. | Rank | ||

| The burden of acute respiratory infections in crisis-affected populations: A systematic review | 2010 | 98 | 1 | 9.8 | 3 |

| War and gender inequalities in health: The impact of armed conflict on fertility and maternal mortality | 2013 | 87 | 2 | 12.4 | 1 |

| Effect of early detection and treatment on malaria related maternal mortality on the north-western border of Thailand 1986–2010 | 2012 | 72 | 3 | 9 | 4 |

| A study of refugee maternal mortality in 10 countries, 2008–2010 | 2012 | 51 | 4 | 6.4 | 6 |

| Energy services for refugees and displaced people | 2016 | 40 | 5 | 10 | 2 |

| High rates of pneumonia in children under two years of age in a south east Asian refugee population | 2013 | 38 | 6 | 5.4 | 9 |

| Evaluating a vocational training programme for women refugees at the Zaatari camp in Jordan: women empowerment: A journey and not an output | 2016 | 32 | 7 | 8 | 5 |

| Neonatal intensive care in a Karen refugee camp: A 4-year descriptive study | 2013 | 29 | 8 | 4.1 | 10 |

| Urban crises and the new urban agenda | 2016 | 24 | 9 | 6 | 8 |

| Challenges and opportunities of new energy schemes for food security in humanitarian contexts: A selective review | 2017 | 19 | 10 | 6.3 | 7 |

| Development Goals | Count of Publications with a Study-Specified Development Goal | |

|---|---|---|

| MDG1 | Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger | 3 |

| MDG2 | Achieve universal primary education | 1 |

| MDG3 | Promote gender equality and empower women | 1 |

| MDG4 | Reduce child mortality | 5 |

| MDG5 | Improve maternal health | 7 |

| MDG6 | Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases | 1 |

| MDG7 | Ensure environmental sustainability | 2 |

| SDG1 | No poverty | 1 |

| SDG2 | Zero hunger | 1 |

| SDG3 | Health and well-being | 14 |

| SDG4 | Quality education and promote lifelong learning | 14 |

| SDG5 | Gender equality | 5 |

| SDG6 | Water and sanitation | 3 |

| SDG7 | Affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy | 5 |

| SDG8 | Sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth | 2 |

| SDG9 | Industry, innovation, and infrastructure | 1 |

| SDG10 | Reduced inequalities | 1 |

| SDG11 | Sustainable cities and communities | 3 |

| SDG13 | Climate action | 1 |

| SDG16 | Peace, justice, and strong institutions | 6 |

| SDG17 | Partnerships for the goals | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wardeh, M.; Marques, R.C. Sustainability in Refugee Camps: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147686

Wardeh M, Marques RC. Sustainability in Refugee Camps: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sustainability. 2021; 13(14):7686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147686

Chicago/Turabian StyleWardeh, Mai, and Rui Cunha Marques. 2021. "Sustainability in Refugee Camps: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Sustainability 13, no. 14: 7686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147686

APA StyleWardeh, M., & Marques, R. C. (2021). Sustainability in Refugee Camps: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sustainability, 13(14), 7686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147686