The Dynamics of Subjective Career Success: A Qualitative Inquiry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

Self-Regulation Process as Context for Changing SCS Perceptions

3. Methods

3.1. Study Sample

3.2. Sampling Strategy

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Shift Component 1: Quitting Striving for Financial Security and Recognition

R63 (early-career): “Yes, in the beginning, we have to imagine that we should get a job that offers like, you know, money for us, no matter how difficult it is.”

R53 (mid-career): “Being able to make enough money was very important in the beginning.”

R36 (early-career): “Oh definitely yeah, it has changed. First, I wanted just money, I just wanted to make as much money as possible.”

R53 (mid-career): “At some point, you realize that enough is enough, that it’s nice to have. It sounds very cocky, but I don’t mean anything by it. You have a certain need, which is enormous in the beginning. You want to buy a house, buy a car, and you want to go on holiday while your pay is still low. At some point, your wages go up. The weird thing is that the costs go down. You have the car, you have the house, and the rent goes down. At some point, the lines cross each other, and from that point on, nothing […] matters anymore. I don’t care about it anymore. Maybe a little, but it’s not a motivator anymore.”

R51 (late-career): [Referring to a personal mantra] “I have to perform, and everyone has to tell me I am doing an excellent job.”

R43 (mid-career): “When I was your age, I could only think of one or two years ahead of me that I want to do this, or I want to achieve this title.”

R14 (early-career): “In the beginning, you don’t know anything about work. You are just having the first experience. And afterwards, you start to meet other people, […] and you listen to your colleagues and their experiences. So, I believe that my goals also changed […]. Having work–life balance is a main goal. In the end, when you have this personal life, and when you are happy, then you feel that you are better.”

R62 (mid-career): ‘I believed for way too long that if I work hard enough, I will become happy. Back then, I had that good job and lots of money. I remember what I thought back then: hmm, this isn’t it really… ha ha.”

4.2. Shift Component 2: Increased Focus on Personal Development across the Career

R53 (mid-career): “Now I’m motivated by lifelong learning. I can’t do anything else. […] It’s just important. It will become more important. Right now, I am still able to learn, but soon I’ll be 50 years old, and then you still need to matter. […] If you get fired, you won’t be hired again, so you need to stay current”.

R43 (mid-career): “At the beginning, it was like achieving new technologies, learning new things, making good money. This has been going on for a long time. Learning new things made you feel the discomfort zone staying with you for ten years. You’re always learning new things.

R36 (early-career): “I realized that, regarding work, it’s more important to feel that you are learning something.”

4.3. Shift Component 3: Stronger Emphasis on Work–Life Balance across the Career

R53 (mid-career): “First, it was getting everything there is to get, and now, I don’t have it at all. Career success is about doing what you feel comfortable doing, not achieving the maximum.”

R11 (early-career): “I think over time the thing that changes the most is the work–life balance thing, where in the beginning you’re like I can work all day. Like when I had my own business, I worked 16 h days, right; I really didn’t care a lot. But now, I think when you become older, you care more about actually the time you spend outside of work. So, that was probably one that changes a lot over time, I would say.”

R45 (early-career): “Career success is working on something that I really like, I enjoy doing it every day, having work–life balance, so I can go home and I really enjoy my life. If I’m working in a very good company with a big name, but have no work–life balance, it’s meaningless to me.”

R43 (mid-career): “Now, career success is a part of a big picture, so life is the big umbrella, and then career and career success is only part of it. When you are younger, you don’t think of the whole picture. You think of the title, the money, the car, but now, my family comes first.”

R35 (early-career): “Now, I think it’s like being successful in your career is like having a nice, balanced life.”

4.4. Shift Component 4: Shift toward Being of Service to Others

R52 (late-career): “I am very happy I can contribute to something, that I can be there for young people—people that need my help. It moved a lot from wanting to be told I am great toward contributing to others. I like this development.”

R57 (late-career): “In the beginning, I thought I really wanted to work for a big company, like […], and build a career there. Currently, it is completely different. I am all about entrepreneurship, which is much more fun. That is why I am so happy that today’s youth don’t feel attracted to big corporates and want to start their own business. They want to add something of value. I want to support society.”

4.5. No Shift in SCS Perception

R18 (early-career): “No, not really. All these things that we have been talking about are the things that I have in my mind since I started working. Well, it’s not so long, so it’s still the same.”

R13 (early-career): “Not really… The thing is that I don’t have a career for that long… But I think the core has remained the same. My definition has remained the same.”

R10 (mid-career): “I would say it did not change much over time, because I always wanted to give my best. I always wanted to contribute in a way to the greater good by way of sustainability”

R8 (mid-career): “I can’t say that they change over time, because they’re also like a part of who I am.”

R34 (early-career): “First of all I need to do what I like, and I am doing what I like. I need to be unique among my team members, and also I am unique among my team members. I need to gain more money, and I’m gaining more money, so I can say no. It didn’t change until now.”

R39 (early-career): “Mm hmm, I think no, I didn’t change my definition, because the definition of career success for me has always been to reach high positions.”

R47 (early-career): “I think the definition has not changed for me. Career success is important in my personal case and not applicable to anyone, but in my personal case, I would consider myself as having a successful career if I managed to have my own business running and functioning and doing well. In this case, the chocolate brand that I want to start in a few years—that’s my definition of success, and I’ve always had it, so I don’t know, for somebody else, maybe it would be a CEO of a company, or whatever industry. But in my case, I always had this vision since I was a teenager, so no, I would say that it has not changed.”

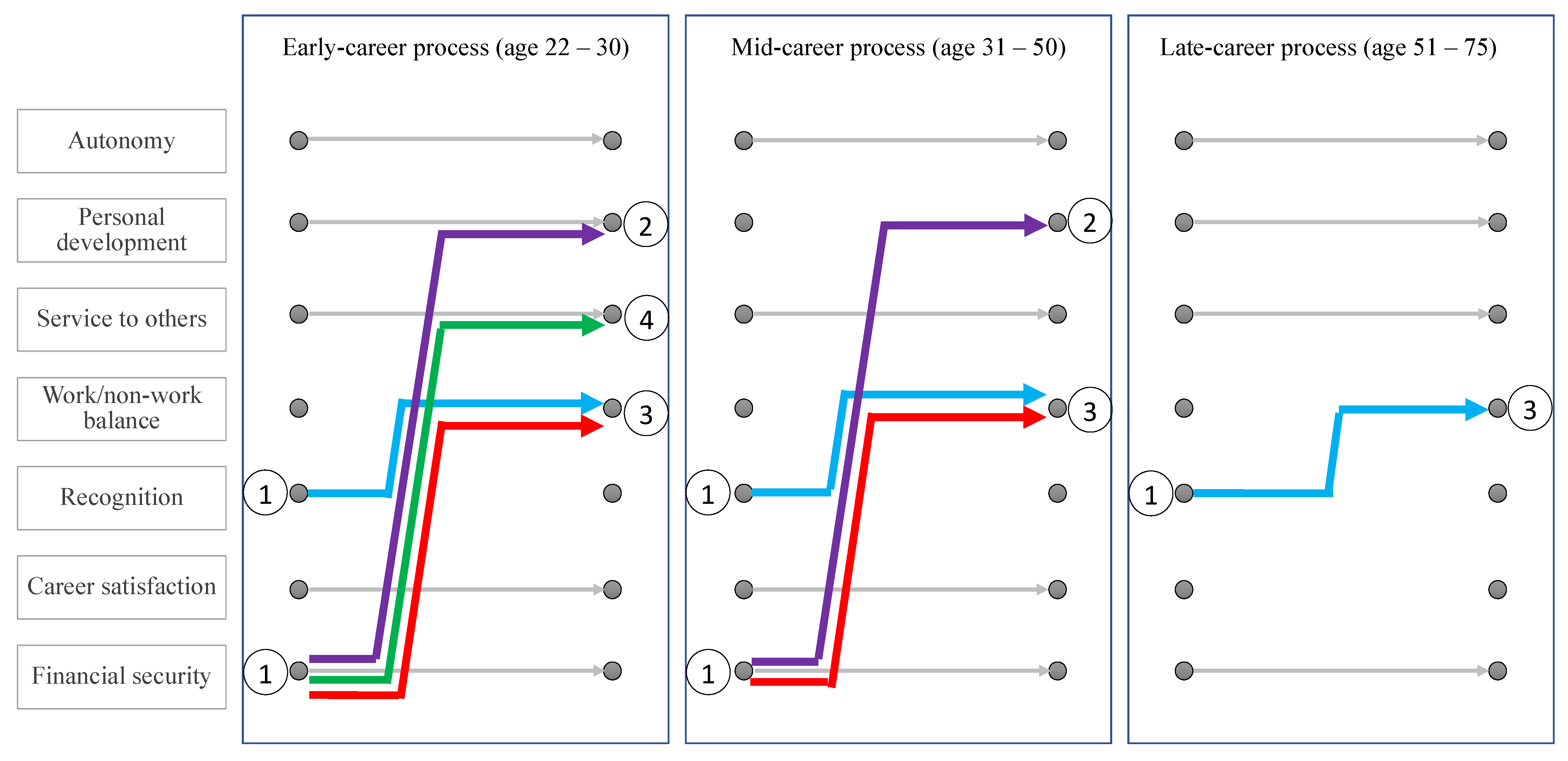

4.6. Overview of Changes in SCS Perceptions

5. Discussion

5.1. Developing Personality as a Mechanism for SCS Change

5.2. Changing Motivation and Time Perspective as Mechanisms for SCS Change

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Protocol Questions

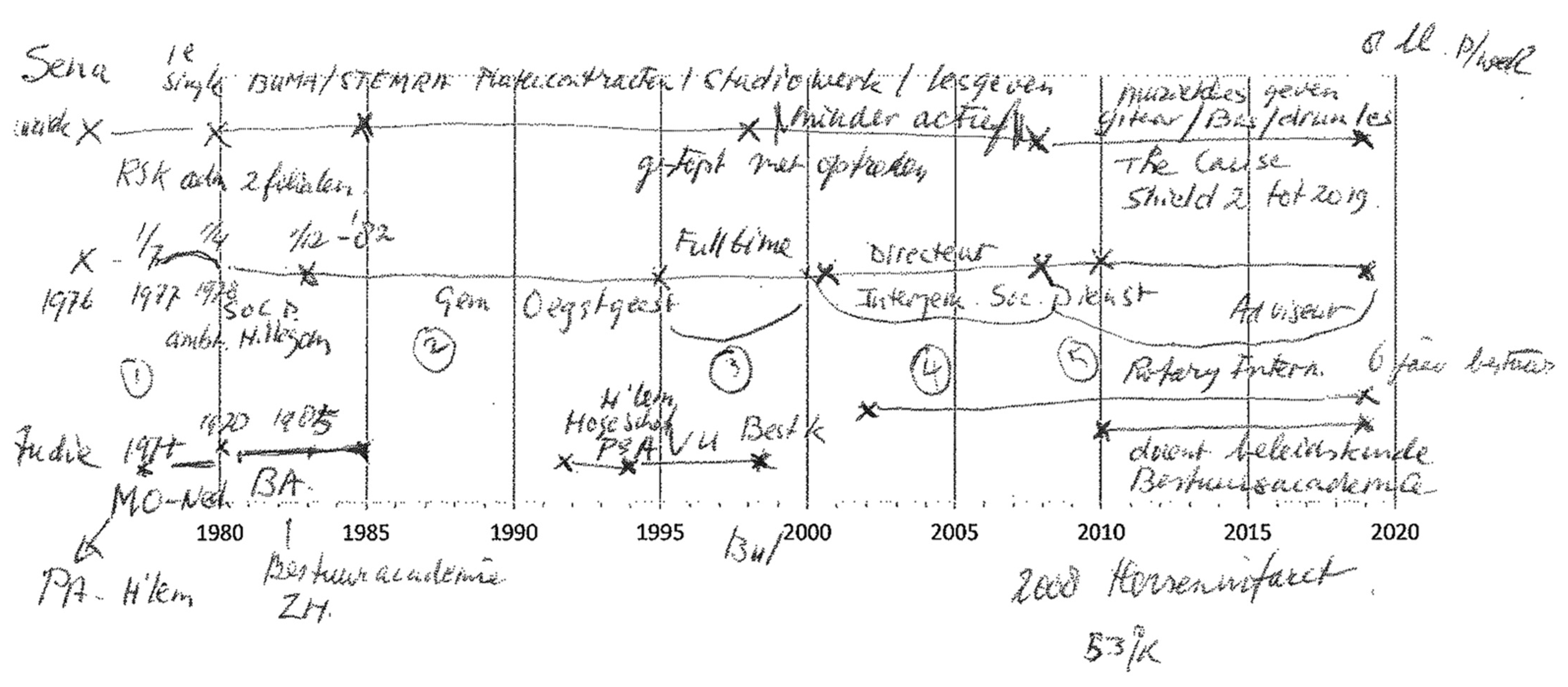

- [The interviewer shows the SCS aspects and scores them with the respondent].

- Denote pivotal moments and key transitional periods from your career in the timeline below. You may use crosses or arrows. [Respondent creates career timeline].Per pivotal moment and key transitional period:

- Describe your own influence in this career moment/period.

- Describe the influence of your environment (e.g., peers) in this career moment/period.

- How content are you with the outcome of this career moment/period?

- Did your definition of career success change over the course of your career?

- When did these changes occur on your career timeline?

- If so, why did your definition of career success change?

Appendix B. Overview of SCS Aspects, Descriptions, and Example Items

| SCS Aspects | Description | Example Items: I Feel My Career is Successful When. |

| 1 Autonomy | personal ownership and accomplishments, carrying responsibility for self-nurtured projects | I have developed and been responsible for my own projects/…I have felt as though I am in charge of my own career. |

| 2 Personal development | personal growth and acquiring abilities; acquiring knowledge and skills | I have expanded my skillsets to perform better |

| 3 Influence | taking pride in seeing the effects of personal influence | decisions that I have made have impacted my organization |

| 4 Service to others | service to others, to be able to give | I believe my work has made a difference |

| 5 Work–life balance | achieving balance between work and non-work commitments | I have been able to be a good employee while maintaining quality non-work relationships |

| 6 Quality work | taking pride in work outcomes | I am proud of the quality of the work I have produced |

| 7 Recognition | external affirmation | I have been recognized for my contributions |

| 8 Career satisfaction | positive affect on overall career experiences | my career is personally satisfying |

| 9 Financial security | being able to provide the basic necessities for living | I have been able to provide the basic necessities for living |

| 10 Financial success | progressive financial accomplishments; being able to successively make more money over the course of the career | I have been able to progressively make more money |

| 11 Positive relationships | high-quality work-related relationships | I get along well with my colleagues |

References

- Arthur, M.B.; Hall, D.T.; Lawrence, B.S. Handbook of Career Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Super, E.D.; Jordaan, J.P. Career development theory. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 1973, 1, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, D.J. The Seasons of a Man’s Life; Random House Digital, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Mainiero, L.A.; Sullivan, S.E. Kaleidoscope careers: An alternate explanation for the “opt-out “revolution. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2005, 19, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, M.B.; Khapova, S.; Wilderom, C.P.M. Career success in a boundaryless career world. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D.; Hirschi, A.; Dries, N. Antecedents and Outcomes of Objective versus Subjective Career Success: Competing Perspectives and Future Directions. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 35–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunz, H.P.; Heslin, P.A. Reconceptualizing career success. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Eby, L.T.; Sorensen, K.L.; Feldman, D.C. Predictors of Objective and Subjective Career Success: A Meta-Analysis. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 367–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, K.M.; Ureksoy, H.; Rodopman, O.B.; Poteat, L.F.; Dullaghan, T.R. Development of a new scale to measure subjective career success: A mixed-methods study. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 128–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J.; Tims, M. Crafting your career: How career competencies relate to career success via job crafting. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 66, 168–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wille, B.; De Fruyt, F.; Feys, M. Big Five Traits and Intrinsic Success in the New Career Era: A 15-Year Longitudinal Study on Employability and Work-Family Conflict. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 62, 124–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J.; Kubasch, S. #Trending topics in careers: A review and future research agenda. Career Dev. Int. 2017, 22, 586–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckhausen, J.; Wrosch, C.; Schulz, R. A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 32–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schein, E.H. How career anchors hold executives to their career paths. Personnel 1975, 52, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Heslin, P.A. Conceptualizing and evaluating career success. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrhofer, W. Career success across the globe: Insights from the 5C project. Organ. Dyn. 2016, 45, 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Isaacowitz, D.M.; Charles, S.T. Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, D.T.A.M.; De Lange, A.H.; Jansen, P.G.W.; Kanfer, R.; Dikkers, J.S.E. Age and work-related motives: Results of a meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 197–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hughes, E.C. Men and Their Work; Free Press: Glen Coe, Scotland, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Abele, A.E.; Spurk, D.; Volmer, J. The construct of career success: Measurement issues and an empirical example. J. Labour Mark. Res. 2011, 43, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abele, A.E.; Hagmaier, T.; Spurk, D. Does Career Success Make You Happy? The Mediating Role of Multiple Subjective Success Evaluations. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 1615–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brentlinger, W.H.; Thorndike, E.L.; Bregman, E.O.; Lorge, I.; Metcalfe, Z.F.; Robinson, E.E.; Woodyard, E. Prediction of Vocational Success. Am. J. Psychol. 1935, 47, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. Career anchors revisited: Implications for career development in the 21st century. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1996, 10, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Fung, H.H.-L.; Charles, S.T. Socioemotional Selectivity Theory and the Regulation of Emotion in the Second Half of Life. Motiv. Emot. 2003, 27, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysova, E.I.; Allan, B.A.; Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D.; Steger, M.F. Fostering meaningful work in organizations: A multi-level review and integration. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lips-Wiersma, M.; Wright, S. Measuring the meaning of meaningful work: Development and validation of the Comprehensive Meaningful Work Scale (CMWS). Group Organ. Manag. 2012, 37, 655–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niks, I.M. Balance at Work: Discovering Dynamics in the Demand-Induced Strain Compensation Recovery (DISC-R) Model; Technische Universiteit Eindhoven: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Parasuraman, S.; Wormley, W.M. Effects of Race on Organizational Experiences, Job Performance Evaluations, and Career Outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smale, A.; Bagdadli, S.; Cotton, R.; Russo, S.D.; Dickmann, M.; Dysvik, A.; Gianecchini, M.; Kaše, R.; Lazarova, M.; Reichel, A.; et al. Proactive career behaviors and subjective career success: The moderating role of national culture. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heckhausen, J.; Wrosch, C.; Schulz, R. Agency and Motivation in Adulthood and Old Age. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 191–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooij, D.T.A.M.; Zacher, H.; Wang, M.; Heckhausen, J. Successful aging at work: A process model to guide future research and practice. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2020, 13, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckhausen, J.; Schulz, R. The primacy of primary control is a human universal: A reply to Gould’s (1999) critique of the life-span theory of control. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 106, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckhausen, J.; Schulz, R. A life-span theory of control. Psychol. Rev. 1995, 102, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, R.; Heckhausen, J. A life span model of successful aging. Am. Psychol. 1996, 51, 702–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Ibáñez, M. Framing the Social World with Photo-Elicitation Interviews. Am. Behav. Sci. 2004, 47, 1507–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, D. Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Vis. Stud. 2002, 17, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedeian, A.G. The measurement and conceptualization of career stages. J. Career Dev. 1991, 17, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogson, E.C.; Cober, A.B.; Doverspike, D.; Rogers, J.R. Differences in self-reported work ethic across three career stages. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 62, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintzman, D.L. Research Strategy in the Study of Memory: Fads, Fallacies, and the Search for the “Coordinates of Truth. ” Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erikson, E.H. Life History and the Historical Movement; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Goodson, I. The Story of Life History: Origins of the Life History Method in Sociology. Identit 2001, 1, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehman, J.; Glaser, V.; Eisenhardt, K.M.; Gioia, D.; Langley, A.; Corley, K.G. Finding Theory–Method Fit: A Comparison of Three Qualitative Approaches to Theory Building. J. Manag. Inq. 2018, 27, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gephart, R.P., Jr. Qualitative research and the Academy of Management Journal; Academy of Management Briarcliff Manor: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketokivi, M.; Mantere, S. Two strategies for inductive reasoning in organizational research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 315–333. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.W.; Lee, T. Using Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R.; Sablynski, C.J. Qualitative Research in Organizational and Vocational Psychology, 1979–1980. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 55, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friese, S. Qualitative Data Analysis with ATLAS; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, A. Strategies for theorizing from process data. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McAdams, D.P.; Hart, H.M.; Maruna, S. The Anatomy of Generativity, in Generativity and Adult Development: How and Why We Care for the Next Generation; McAdams, D.P., De St. Aubin, E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 7–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, M.C.; Lee, K. Age trends in HEXACO-PI-R self-reports. J. Res. Pers. 2016, 64, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Ashton, M.C. Psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and Narcissism in the Five-Factor Model and the HEXACO model of personality structure. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2005, 38, 1571–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, D.; Van De Voorde, K. How changes in subjective general health predict future time perspective, and development and generativity motives over the lifespan. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L. The Influence of a Sense of Time on Human Development. Science 2006, 312, 1913–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kanfer, R.; Ackerman, P.L. Aging, adult development, and work motivation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 440–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brandstätter, V.; Schüler, J. Action crisis and cost–benefit thinking: A cognitive analysis of a goal-disengagement phase. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 49, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wrosch, C.; Scheier, M.F.; Miller, G.E.; Schulz, R.; Carver, C. Adaptive Self-Regulation of Unattainable Goals: Goal Disengagement, Goal Reengagement, and Subjective Well-Being. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 1494–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| ID | Pseudonym | Sector | Gender | Age at Interview (Years) | Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saskia | Recruiting | Female | 34 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 2 | Robert | FMCG | Male | 75 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 3 | Hans | Professional services | Male | 62 | Master’s degree |

| 4 | Sander | IT | Male | 33 | Master’s degree |

| 5 | Margot | IT | Female | 38 | Master’s degree |

| 6 | Sara | IT | Female | 32 | Master’s degree |

| 7 | Sarah | PR | Female | 52 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 8 | Chantal | Finance | Female | 31 | Master’s degree |

| 9 | Karel | Professional services | Male | 61 | High school degree |

| 10 | Anton | Engineering | Male | 32 | Master’s degree |

| 11 | Egbert | IT | Male | 30 | Master’s degree |

| 12 | Mariam | Tourism | Female | 39 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 13 | Daniela | IT | Female | 24 | Master’s degree |

| 14 | Laura | Professional services | Female | 28 | Master’s degree |

| 15 | Sarah | Hospitality | Female | 24 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 16 | Omar | Hospitality | Male | 25 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 17 | Frank | Hospitality | Male | 25 | Master’s degree |

| 18 | Annemarie | Professional services | Female | 26 | Master’s degree |

| 19 | Rutger | Engineering | Male | 28 | Master’s degree |

| 20 | Rick | Automotive | Male | 61 | High school degree |

| 21 | Leonie | Trade union | Female | 52 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 22 | Jos | Finance | Male | 25 | Master’s degree |

| 23 | Stephanie | Hospitality | Female | 27 | Master’s degree |

| 24 | Marieke | Entertainment | Female | 25 | Master’s degree |

| 25 | Ellen | Hospitality | Female | 27 | Master’s degree |

| 26 | Katrien | Professional services | Female | 26 | Master’s degree |

| 27 | José | Consultancy | Male | 25 | Master’s degree |

| 28 | Dita | Construction | Female | 26 | Master’s degree |

| 29 | Jan | IT | Male | 25 | Master’s degree |

| 30 | Chloe | Professional services | Female | 27 | Master’s degree |

| 31 | Yvonne | Education | Female | 28 | Master’s degree |

| 32 | Danielle | IT | Female | 25 | Master’s degree |

| 33 | Meta | FMCG | Female | 28 | Master’s degree |

| 34 | Gerard | IT | Male | 29 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 35 | Heleen | IT | Female | 25 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 36 | Henk | IT | Male | 26 | Master’s degree |

| 37 | Monique | IT | Female | 29 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 38 | Steven | IT | Male | 27 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 39 | Mandy | Education | Female | 27 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 40 | Roberto | Finance | Male | 26 | Master’s degree |

| 41 | Dennis | FMCG | Male | 29 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 42 | Ruben | IT | Male | 34 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 43 | Simone | HR | Female | 37 | Master’s degree |

| 44 | Louis | IT | Male | 39 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 45 | Benedita | IT | Female | 27 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 46 | Roderik | FMCG | Male | 22 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 47 | Frank | FMCG | Male | 28 | Master’s degree |

| 48 | Erik | IT | Male | 27 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 49 | Maria | FMCG | Female | 22 | Master’s degree |

| 50 | Henk | IT | Male | 29 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 51 | Ton | Government | Male | 63 | Master’s degree |

| 52 | Robin | Government | Female | 56 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 53 | Anton | Manufacturing | Male | 43 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 54 | Diana | Manufacturing | Female | 46 | Master’s degree |

| 55 | Jos | PR | Male | 56 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 56 | Catarina | Healthcare | Female | 44 | Master’s degree |

| 57 | Michael | Capital Goods | Male | 62 | Master’s degree |

| 58 | Thomas | Aviation | Male | 72 | Master’s degree |

| 59 | Marta | Government | Female | 51 | Master’s degree |

| 60 | Linde | Professional services | Female | 67 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 61 | Daniela | Healthcare | Female | 49 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 62 | Gaida | Manufacturing | Female | 50 | Bachelor’s degree |

| 63 | Wim | Fashion | Male | 24 | Master’s degree |

| Aspect | Example Quotes |

|---|---|

| 1 Autonomy | R9 (late-career): “I think you get the most happiness when you’re working for yourself than if you’re working for somebody else.” R32 (early career): “I believe that in the modern world it’s quite important to have as much flexibility as you want.” |

| 2 Personal development | R53 (mid-career): “Now I’m motivated by lifelong learning. I can’t do anything else. […] It’s just important. It will become more important. Right now, I am still able to learn but soon I’ll be 50 years old and then you still need to matter. […] If you get fired you won’t be hired again so you need to stay current”. R36 (early-career): ‘[…] to feel motivated about your work, your job, and to feel that you are learning something.” |

| 3 Influence | R40 (early-career): “You start looking into other things, such as, I would say, the impact that you [have] on your colleagues and staff and the team you’re working with, also externally on society, like what you do influence and effect on the surroundings and the people around you.” |

| 4 Service to others | R20 (late-career): “To give others the opportunity to evolve, to grow, and have their moments of success.” R50 (early-career): “Now it has changed a lot, for example, how to be able to share this knowledge and to find someone who can use the knowledge you have, so transferring this information to other people is considered a success for me.” |

| 5 Work–life balance | R45 (early-career): “Career success is working in something that I really like, I enjoy doing it every day, having work life balance, so I can go home and really enjoy my life. If I’m working in a very good company with a big name, but have no work life balance, it’s meaningless to me.” |

| 6 Quality work | R58 (late-career): “During my time at [Company], I’ve been asked many times to speak about my work. At [Dutch University], I gave many lectures about alliances for international master students that also had alliances in their course contents.” |

| 7 Recognition | R40 (early-career): “[A] very important part is getting recognized and, you know, feeling appreciated for what you do.” |

| 8 Career satisfaction | R27 (early-career):“I generally think that the times that I had more success in my life were the times that I was fully enjoying what I was doing.” R63 (early-career): “So for me, like, the most important thing is to do something that I really like to do, and that I wake up, and I want to do it, because it’s of my personal interest.” |

| 9 Financial security | R3 (late-career): “First of all, it’s financial stability. I mean, I need to earn a living.” |

| 10 Financial success | R36 (early-career): “First, I wanted just money. I just wanted to make as much money as possible.” R37 (early-career): “I said that [with] a good career, that you should have a big salary, so I always choose the company with the biggest salary.” |

| 11 Positive relationships | R18 (early-career): “It’s important the feeling that I have and also the feedback from the other persons that work with me. So, in that sense, if I have a good feedback, and it’s going in the same way as what I feel, then I’m sure that I’m achieving those goals.” |

| Nr. | Shift Component | Experiences |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quitting striving for financial security and recognition | Goals pertaining to financial security and recognition do not motivate anymore. This shift away from financial security and recognition is reported to occur in the early- and mid-career. |

| 2 | Increased focus on personal development | Workers seeking personal development want to expand their horizon, because goals concerning personal development have become more attractive. |

| 3 | Stronger emphasis on work–life balance | Workers seeking more work–life balance seem to choose this option to minimize investments in work in general, because non-work goals have become more attractive. |

| 4 | A shift toward service to others | Workers going for service to others also have high career outcomes. They have gained an expanded definition of self, as a process of maturation (generativity as a sign of maturation) and have experienced joy and inspiration in working with others in a communal sense. |

| 5 | No shift in success criteria | Workers experience consistent SCS perceptions across career phases. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hupkens, L.; Akkermans, J.; Solinger, O.; Khapova, S. The Dynamics of Subjective Career Success: A Qualitative Inquiry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7638. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147638

Hupkens L, Akkermans J, Solinger O, Khapova S. The Dynamics of Subjective Career Success: A Qualitative Inquiry. Sustainability. 2021; 13(14):7638. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147638

Chicago/Turabian StyleHupkens, Leon, Jos Akkermans, Omar Solinger, and Svetlana Khapova. 2021. "The Dynamics of Subjective Career Success: A Qualitative Inquiry" Sustainability 13, no. 14: 7638. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147638

APA StyleHupkens, L., Akkermans, J., Solinger, O., & Khapova, S. (2021). The Dynamics of Subjective Career Success: A Qualitative Inquiry. Sustainability, 13(14), 7638. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147638