Plastic Waste Sorting Intentions among University Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Plastic Waste in Nigeria

2.2. Waste Governance in Nigeria

2.3. Waste Sorting Practices at Universities

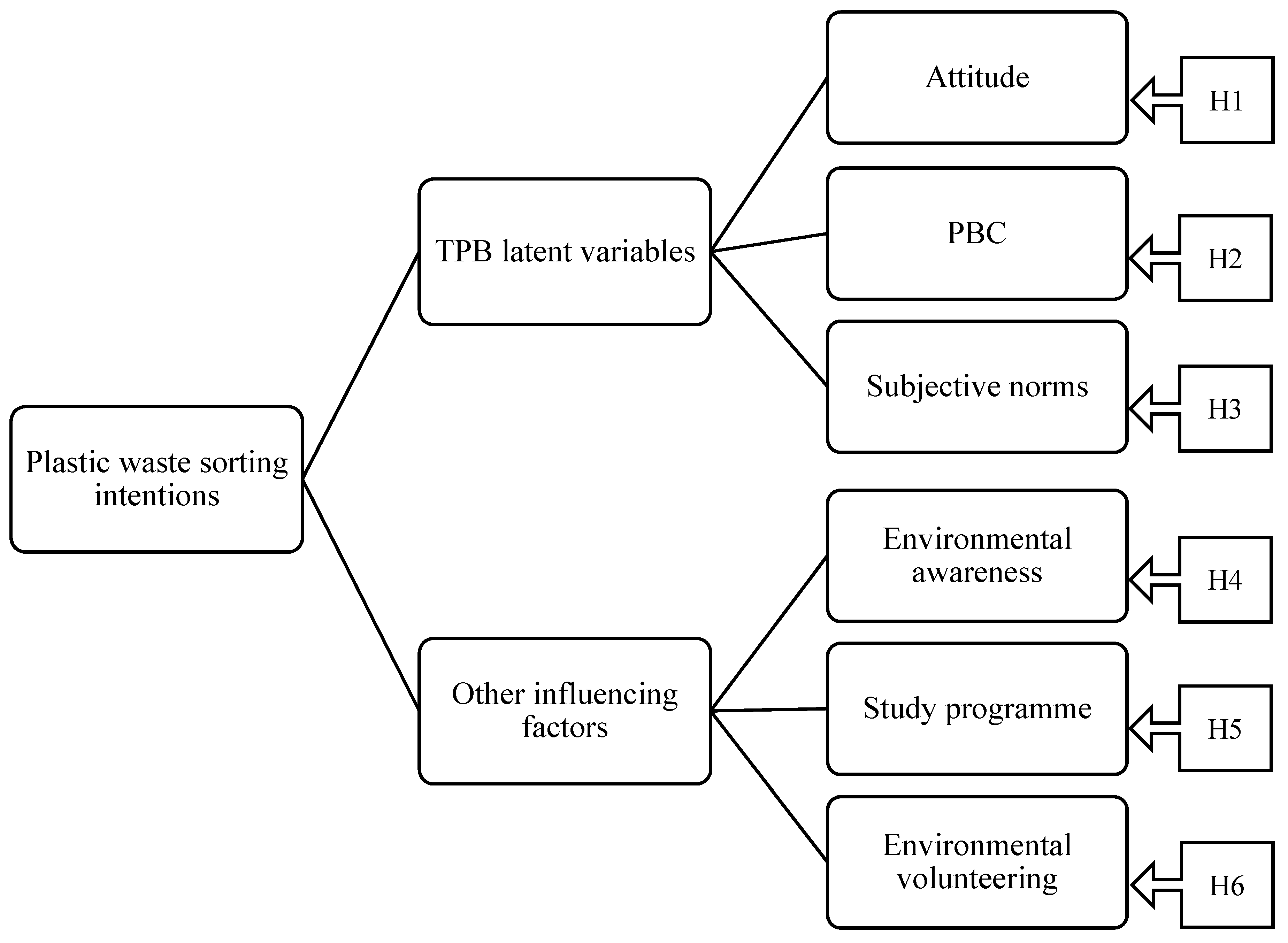

2.4. Conceptual Model Development–Theory of Planned Behavior Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

3.3. TPB Construct

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of the Respondents

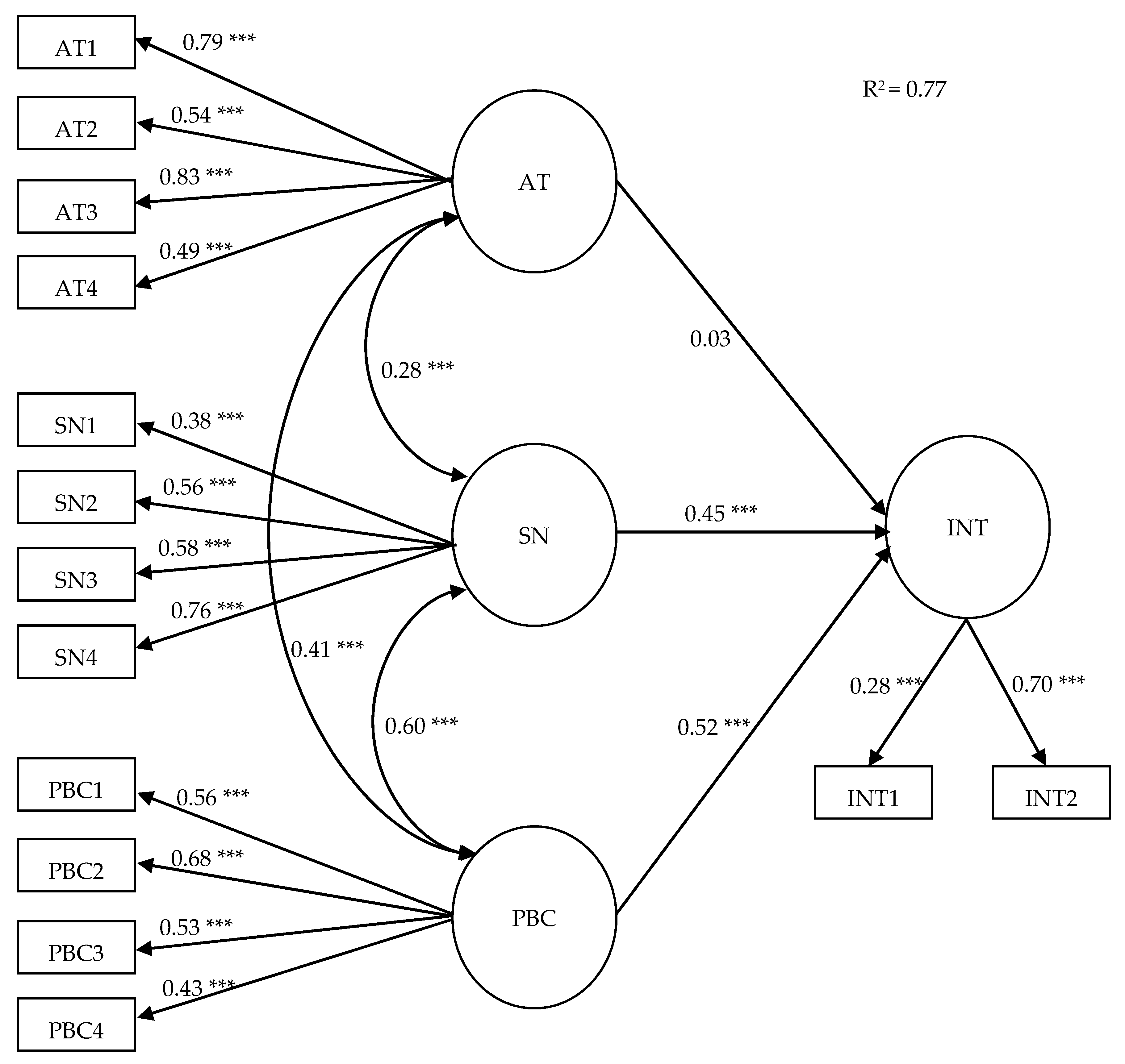

4.2. Model Criteria

4.3. Attitude towards Plastic Waste Sorting

4.4. Subjective Norm and PBC towards Plastic Waste Sorting

4.5. Other Factors Influencing Student’s Plastic Waste Sorting Intentions

4.6. Contribution to Practice

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dumbili, E.; Henderson, L. The Challenge of Plastic Pollution in Nigeria. In Plastic Waste and Recycling; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ike, C.C.; Ezeibe, C.C.; Anijiofor, S.C.; Nik Daud, N.N. Solid Waste Management in Nigeria: Problems, Prospects, and Policies. J. Solid Waste Technol. Manag. 2018, 44, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldometer. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/nigeria-population/ (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Sondo, R.; Amoko, M. Cameroon Environmentalists Tackle Plastic Pollution in Wouri River. 2021. Available online: https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20210605-cameroon-environmentalists-tackle-plastic-pollution-in-wouri-river (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Babayemi, J.O.; Ogundiran, M.B.; Weber, R.; Osibanjo, O. Initial Inventory of Plastics Imports in Nigeria as a Basis for More Sustainable Management Policies. J. Health Pollut. 2018, 8, 180601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duru, R.U.; Ikpeama, E.E.; Ibekwe, J.A. Challenges and Prospects of Plastic Waste Management in Nigeria. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2019, 1, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ayodele, T.R.; Alao, M.A.; Ogunjuyigbe, A.S.O. Recyclable Resources from Municipal Solid Waste: Assessment of Its Energy, Economic and Environmental Benefits in Nigeria. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, A.O.; Achi, C.G.; Sridhar, M.K.C.; Donnett, C.J. Solid Waste Management Practices at a Private Institution of Higher Learning in Nigeria. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 35, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeah, C.; Roberts, C.L. Waste Governance Agenda in Nigerian Cities: A Comparative Analysis. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofoworola, O.F. Recovery and Recycling Practices in Municipal Solid Waste Management in Lagos, Nigeria. Waste Manag. 2007, 27, 1139–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwanza, B.G.; Mbohwa, C.; Telukdarie, A. Strategies for the Recovery and Recycling of Plastic Solid Waste (PSW): A Focus on Plastic Manufacturing Companies. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 21, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniran, A.E.; Nubi, A.T.; Adelopo, A.O. Solid Waste Generation and Characterization in the University of Lagos for a Sustainable Waste Management. Waste Manag. 2017, 67, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojuola, R.N.; Alant, B.P. Sustainable Development and Energy Education in Nigeria. Renew. Energy 2019, 139, 1366–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifegbesan, A. Waste Management Awareness, Knowledge, and Practices of Secondary School Teachers in Ogun State, Nigeria-Implications for Teacher Education. J. Solid Waste Technol. Manag. 2011, 37, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanle, O.; Shittu, O. Value Chain Actors and Recycled Polymer Products in Lagos Metropolis: Toward Ensuring Sustainable Development in Africa’s Megacity. Resources 2018, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shen, L. Chapter 13—Plastic Recycling. In Handbook of Recycling; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Adeyemi, A.S.; Olorunfemi, J.F.; Adewoye, T.O. Waste Scavenging in Third World Cities: A Case Study in Ilorin, Nigeria. Environmentalist 2001, 21, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzeadibe, T.C. Solid Waste Reforms and Informal Recycling in Enugu Urban Area, Nigeria. Habitat Int. 2009, 33, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babayemi, J.O.; Nnorom, I.C.; Osibanjo, O.; Weber, R. Ensuring Sustainability in Plastics Use in Africa: Consumption, Waste Generation, and Projections. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2019, 31, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hammed, T.B.; Wandiga, S.O.; Mulugetta, Y.; Sridhar, M.K.C. Improving Knowledge and Practices of Mitigating Green House Gas Emission through Waste Recycling in a Community, Ibadan, Nigeria. Waste Manag. 2018, 81, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd’Razack, N.T.A.; Medayese, S.O.; Shaibu, S.I.; Adeleye, B.M. Habits and Benefits of Recycling Solid Waste among Households in Kaduna, North West Nigeria. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 28, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Liu, K.; Xue, B.; Fujita, T. Creating a “Green University” in China: A Case of Shenyang University. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 61, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fissi, S.; Romolini, A.; Gori, E.; Contri, M. The Path toward a Sustainable Green University: The Case of the University of Florence. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagiliute, R.; Liobikiene, G. University Contributions to Environmental Sustainability: Challenges and Opportunities from the Lithuanian Case. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaffashi, S.; Shamsudin, M.N. Transforming to a Low Carbon Society; an Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour of Malaysian Citizens. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Yang, W.; Shen, X. A Comparison Study of ‘Motivation–Intention–Behavior’ Model on Household Solid Waste Sorting in China and Singapore. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, O.; Daddi, T.; Slabbinck, H.; Kleinhans, K.; Vazquez-Brust, D.; De Meester, S. Assessing the Determinants of Intentions and Behaviors of Organizations towards a Circular Economy for Plastics. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 163, 105069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Williams, I.D.; Kemp, S.; Smith, N.F. Greening Academia: Developing Sustainable Waste Management at Higher Education Institutions. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 1606–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zen, I.S.; Subramaniam, D.; Sulaiman, H.; Saleh, A.L.; Omar, W.; Salim, M.R. Institutionalize Waste Minimization Governance towards Campus Sustainability: A Case Study of Green Office Initiatives in Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1407–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogaji, E. Types and Location of Nigerian Universities. Res. Agenda Work. Pap. 2019, 2019, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.Y.; Yu, T.K.; Chao, C.M. Understanding Taiwanese Undergraduate Students’ pro-Environmental Behavioral Intention towards Green Products in the Fight against Climate Change. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. Experiential and Instrumental Attitudes: Interaction Effect of Attitude and Subjective Norm on Recycling Intention. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 50, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, T.M.W.; Yu, I.K.M.; Wang, L.; Hsu, S.C.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Li, C.N.; Yeung, T.L.Y.; Zhang, R.; Poon, C.S. Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour for Promoting Construction Waste Recycling in Hong Kong. Waste Manag. 2019, 83, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-Environmental Behaviors through the Lens of the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Scoping Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Methodology in the social sciences. In Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, J.M.; Devereux, P.J. Understanding Gender Differences in STEM: Evidence from College Applications✰. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2019, 72, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junsheng, H.; Akhtar, R.; Masud, M.M.; Rana, M.S.; Banna, H. The Role of Mass Media in Communicating Climate Science: An Empirical Evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; McCright, A.M. A Test of the Biographical Availability Argument for Gender Differences in Environmental Behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, S. Theory of planned behaviour. In Cambridge Handbook of Psychology, Health and Medicine; Ayers, S., Baum, A., McManus, C., Newman, S., Wallston, K., Weinman, J., West, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Strydom, W.F. Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior to Recycling Behavior in South Africa. Recycling 2018, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmad, M.S.; Bazmi, A.A.; Bhutto, A.W.; Shahzadi, K.; Bukhari, N. Students’ Responses to Improve Environmental Sustainability Through Recycling: Quantitatively Improving Qualitative Model. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2016, 11, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Tseng, C.P.M.L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y. Intention in Use Recyclable Express Packaging in Consumers’ Behavior: An Empirical Study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, C.A.; Arnold, K. A Study of Environmental Awareness and Attitudes in Ibadan, Nigeria. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2012, 18, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsóka, Á.; Szerényi, Z.M.; Széchy, A.; Kocsis, T. Greening Due to Environmental Education? Environmental Knowledge, Attitudes, Consumer Behavior and Everyday pro-Environmental Activities of Hungarian High School and University Students. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Molina, M.A.; Fernández-Sainz, A.; Izagirre-Olaizola, J. Does Gender Make a Difference in Pro-Environmental Behavior? The Case of the Basque Country University Students. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latent Construct | Description | Symbol |

|---|---|---|

| Attitudes towards plastic recycling and plastic waste sorting | AT | |

| Plastic recycling will improve environmental sanitation. | AT1 | |

| Waste sorting for plastic recycling is a good use of my effort. | AT2 | |

| Waste sorting brings financial reward. | AT3 | |

| Waste sorting is a good use of my free time. | AT4 | |

| Subjective norms towards plastic waste sorting | SN | |

| Classmates will approve of me gathering plastic for recycling. | SN1 | |

| People I revere will be pleased to see me sort plastic. | SN2 | |

| My friends always separate plastic for recycle. | SN3 | |

| It is expected that I sort plastic for recycling. | SN4 | |

| Perceived behavioral control towards plastic waste sorting | PBC | |

| Several opportunities for waste sorting exist around me. | PBC1 | |

| Nothing prevents me from sorting plastic waste regularly. | PBC2 | |

| Choosing to sort plastic is solely dependent on me. | PBC3 | |

| The distance to a recycling centre is very far. | PBC4 | |

| Intention towards plastic waste sorting | INT | |

| I will commence plastic waste sorting from now on. | INT1 | |

| Frequency of my plastic sorting activity in the last 2 weeks. | INT2 |

| TPB Item | FUNAAB (n = 444) | UI (n = 495) | N = 939 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | Total | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 298 | 67.0 | 282 | 57.0 | 580 |

| Female | 146 | 32.0 | 213 | 43.0 | 359 |

| Age | |||||

| ≤18 | 37 | 8.3 | 58 | 11.7 | 95 |

| 18–24 | 345 | 77.7 | 395 | 79.8 | 740 |

| 25–34 | 62 | 14.0 | 42 | 8.5 | 104 |

| Study Program | |||||

| Agriculture | 150 | 33.8 | 173 | 34.9 | 323 |

| Engineering | 150 | 33.8 | 179 | 36.2 | 329 |

| Environment | 144 | 32.4 | 143 | 28.9 | 287 |

| University level | |||||

| 100 L | 42 | 9.5 | 80 | 16.2 | 122 |

| 200 L | 95 | 21.4 | 152 | 30.7 | 247 |

| 300 L | 65 | 14.6 | 121 | 24.4 | 186 |

| 400 L | 144 | 32.4 | 101 | 20.4 | 245 |

| 500 L | 98 | 22.1 | 41 | 8.3 | 139 |

| TPB Item | Mean | SD | Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT1: Plastic recycling will improve environmental sanitation | 6.01 | 1.68 | 0.54 *** |

| AT2: Waste sorting for plastic recycling is a good use of my effort | 5.30 | 1.60 | 0.83 *** |

| AT3: Waste sorting brings financial reward | 5.76 | 1.55 | 0.49 *** |

| AT4: Waste sorting is a good use of my free time | 5.05 | 1.69 | 0.79 *** |

| SN1: Classmates will approve of me gathering plastic for recycling | 3.93 | 1.75 | 0.38 *** |

| SN2: People I revere will be pleased to see me sort plastic | 4.02 | 1.92 | 0.56 *** |

| SN3: My friends always separate plastic for recycling | 2.76 | 1.83 | 0.58 *** |

| SN4: It is expected that I sort plastic for recycling | 3.54 | 1.87 | 0.76 *** |

| PBC1: Several opportunities for waste sorting exists around me | 4.47 | 1.96 | 0.56 *** |

| PBC2: Nothing prevents me from sorting plastic waste regularly | 4.21 | 1.95 | 0.68 *** |

| PBC3: Choosing to sort plastic is solely dependent on me | 4.90 | 1.87 | 0.53 *** |

| PBC4: The distance to a recycling centre is very far | 4.71 | 1.77 | 0.43 *** |

| INT1: I will commence plastic waste sorting from now on | 3.73 | 1.91 | 0.28 *** |

| INT2: Frequency of my plastic sorting activity in the last 2 weeks | 0.68 | 1.65 | 0.70 *** |

| TPB Item | Mean | SD | Loadings | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| University level | 3.03 | 1.28 | 0.01 ** | |

| 1st year (1) | 13 | |||

| 2nd year (2) | 26.3 | |||

| 3rd year (3) | 19.8 | |||

| 4th year (4) | 26.1 | |||

| 5th year (5) | 14.8 | |||

| Study program | 1.96 | 0.81 | 0.02 ** | |

| Agriculture (1) | 34.4 | |||

| Engineering (2) | 35.4 | |||

| Environment (3) | 30.6 | |||

| Environmental awareness–I always follow environmental news. | 1.58 | 0.49 | 0.01 ** | |

| Yes (1) | 41.6 | |||

| No (2) | 58.4 | |||

| Environmental volunteering–I am an active member of an environmental voluntary organization. | 1.87 | 0.33 | 0.001 *** | |

| Yes (1) | 12.8 | |||

| No (2) | 87.2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aikowe, L.D.; Mazancová, J. Plastic Waste Sorting Intentions among University Students. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147526

Aikowe LD, Mazancová J. Plastic Waste Sorting Intentions among University Students. Sustainability. 2021; 13(14):7526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147526

Chicago/Turabian StyleAikowe, Loveth Daisy, and Jana Mazancová. 2021. "Plastic Waste Sorting Intentions among University Students" Sustainability 13, no. 14: 7526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147526

APA StyleAikowe, L. D., & Mazancová, J. (2021). Plastic Waste Sorting Intentions among University Students. Sustainability, 13(14), 7526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147526