Corporate Social and Financial Performance: The Role of Firm Life Cycle in Business Groups

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Hypotheses Development

2.1. Corporate Social and Financial Performance

2.2. The CSP–CFP Sensitivity and Firm Life Cycle Stages

2.3. The CSP–CFP Sensitivity and Chaebol Firm Effects

3. Sample Selection and Model

3.1. Sample Selection

3.2. Identification of FLC Stages

3.3. CSP Measurement

3.4. Model

| CFP | = | Earnings before interest and taxes divided by total assets |

| NW | = | Natural logarithm of the KEJI Index |

| SW | = | Stakeholder-weighted KEJI Index |

| Chaebol | = | A dummy variable equal to one for firms belonging to business groups and zero otherwise |

| SIZE | = | Natural logarithm of total assets |

| GRW | = | Sales growth rate over the previous year |

| LEV | = | Ratio of debt to total assets |

| RND | = | R&D expenses deflated by total assets |

| IND | = | Industry dummy |

| YD | = | Year dummy |

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

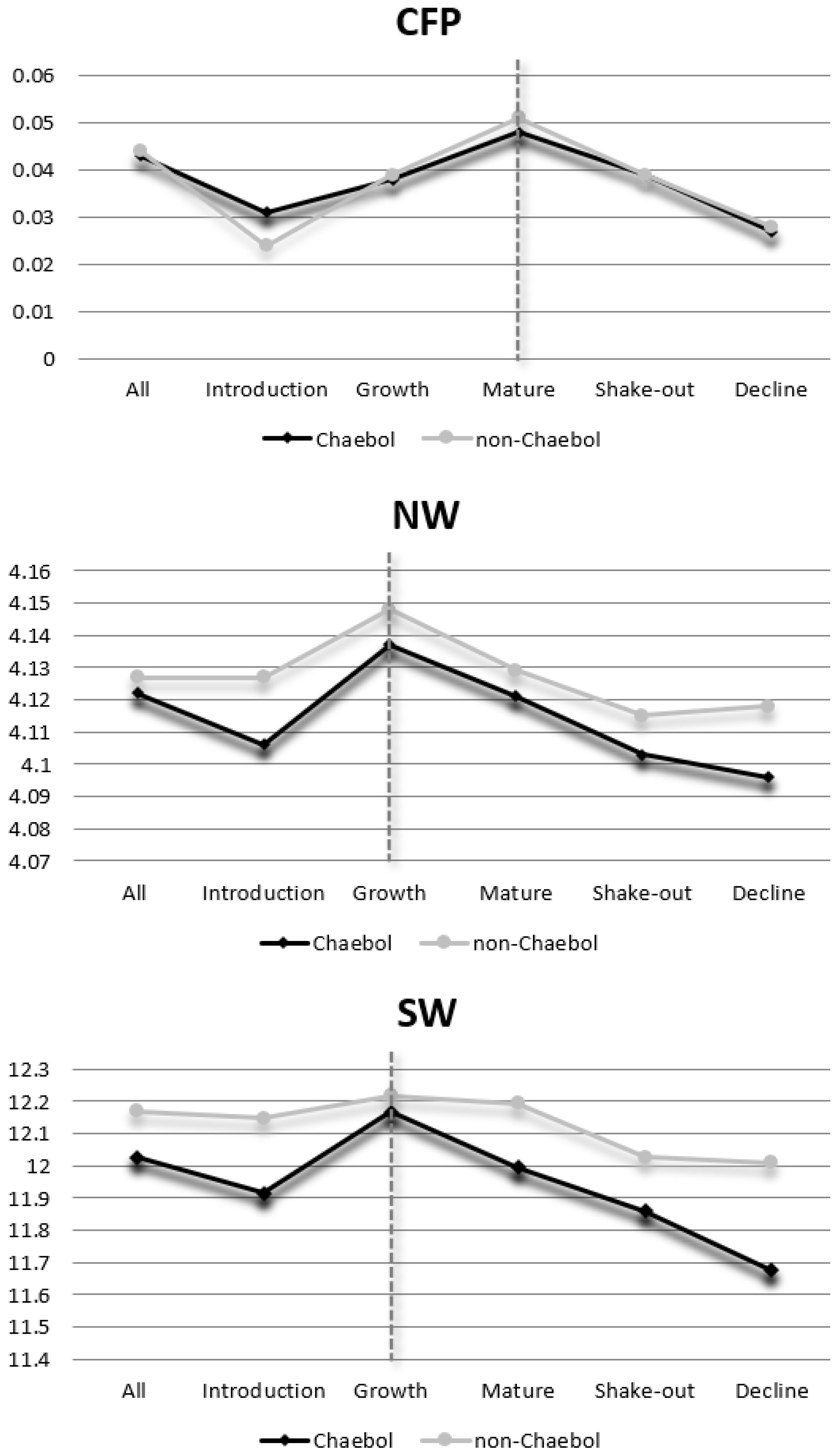

4.2. Correlations between CSP and CFP across FLC Stages

4.3. Relationships between CSP and CFP across FLC Stages

4.4. Chaebols as CSR Commitment

4.5. Endogeneity Tests

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benlemlih, M.; Bitar, M. Corporate social responsibility and investment efficiency. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 647–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Kwark, Y.M.; Choe, C.W. Corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance: Evidence from Korea. Aust. J. Manag. 2010, 35, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cho, S.Y.; Lee, C.; Pfeiffer, R.J., Jr. Corporate social responsibility performance and information asymmetry. J. Account. Public Policy 2013, 32, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D.S.; Li, O.Z.; Yang, A.T. Voluntary non-financial disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. Account. Rev. 2011, 86, 59–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, B.I.; Petrovits, C.; Radhakrishnan, S. Is doing good for you? How corporate charitable contributions enhance revenue growth. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.-J.; Lee, K.-H. The sensitivity of corporate social performance to corporate financial performance: A “time-based” agency theory perspective. Aust. J. Manag. 2021, 46, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platonova, E.; Asutay, M.; Dixon, R.; Mohammad, S. The impact of corporate social responsibility disclosure on financial performance: Evidence from the GCC Islamic banking sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hemingway, C.; Maclagan, P. Managers’ personal values as drivers of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 50, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Venkatachalam, M. Are sin stocks paying the price for accounting sins? J. Account. Audit. Financ. 2011, 26, 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, P. Corporate goodness and shareholder wealth. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 115, 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D.; Wright, P. Guest editors’ introduction corporate social responsibility: Strategic implications. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prior, D.; Surroca, J.; Tribo, J. Are socially responsible managers really ethical? Exploring the relationship between earnings management and corporate social responsibility. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2008, 16, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, B.-J. Audit committees and managerial influence on audit quality: ‘Voluntary’ versus ‘mandatory’ approach to corporate governance. Aust. Account. Rev. 2019, 29, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsam, S. Discretionary accounting choices and CEO compensation. Contemp. Account. Res. 1998, 15, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaver, J.J.; Gaver, K.M. The relation between nonrecurring accounting transactions and CEO cash compensation. Account. Rev. 1998, 73, 235–253. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.-J. Auditors’ economic incentives and the sensitivity of managerial pay to accounting performance. Aust. Account. Rev. 2017, 27, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, V. Cash flow patterns as a proxy for firm life cycle. Account. Rev. 2011, 86, 1969–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Friesen, P.H. A longitudinal study of the corporate life cycle. Manag. Sci. 1984, 30, 1161–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Singh, P. The evolution of CEO compensation over the organizational life cycle: A contingency explanation. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2014, 24, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Su, L.; Zhu, X. Managerial ownership, board monitoring and firm performance in a family-concentrated corporate environment. Account. Financ. 2012, 52, 1061–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morck, R.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R. Management ownership and market valuation: An empirical analysis. J. Financ. Econ. 1988, 20, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.Y.M. An empirical study on the relationship between ownership and performance in a family-based corporate environment. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 2005, 20, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, S.; Djankov, S.; Lang, L. The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations. J. Financ. Econ. 2000, 58, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A. Corporate ownership around the world. J. Financ. 1999, 54, 471–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.-H.; Kang, J.-K.; Kim, J.-M. Tunneling or value Added? Evidence from mergers by Korean business group. J. Financ. 2002, 57, 2695–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.-H.; Jeong, S.W. The value-relevance of earnings and book value, ownership structure, and business group affiliation: Evidence from Korean business groups. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2007, 34, 740–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.-S.; Kang, J.-K.; Lee, I.-M. Business groups and tunneling: Evidence from private securities offerings by Korean Chaebols. J. Financ. 2006, 61, 2415–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baron, D. Private politics, corporate social responsibility and integrated strategy. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2001, 10, 7–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, D.L.; Parnell, J.A.; Crandall, W.; Menefee, M. Organizational life cycle and innovation among entrepreneurial enterprises. J. Small Bus. Strategy 2008, 19, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lynall, M.; Golden, B.; Hillman, A. Board composition from adolescence to maturity: A multi-theoretic view. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, E.L. Life-cycle impacts on the incremental value-relevance of earnings and cash flow measures. J. Financ. Statement Anal. 1998, 4, 40–56. [Google Scholar]

- Koberg, C.S.; Uhlenbruck, N.; Sarason, Y. Facilitators of organizational innovation: The role of life-cycle stage. J. Bus. Ventur. 1996, 11, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Agarwal, N.C. Executive compensation: Examining an old issue from new perspectives. Compens. Benefits Rev. 2003, 35, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, V.; Shank, J.K. Strategic cost management: Tailoring controls to strategies. J. Cost Manag. 1992, 6, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, J.H.; Ramesh, K. Association between accounting performance measures and stock prices: A test of the life cycle hypothesis. J. Account. Econ. 1992, 15, 203–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.; Meckling, W. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency cost and capital structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, A.; Jiang, Y.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Berrone, P.; Walls, J.L. Strategic Use of CSR as a Signal for Good Management; IE Business School Working Paper; IE Business School: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Demsetz, H.; Villalonga, B. Ownership structure and corporate performance. J. Corp. Financ. 2001, 7, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, G.C. Tests of equality between sets of coefficients in two linear regressions. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1960, 28, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Companies traded in the Korea Stock Price Index (KOSPI) market from 2013 to 2018 | 4560 | |

| (1) | Exclude companies that are not manufacturing industries and have closing months other than December | (344) |

| (2) | Exclude companies that do not have the KEJI Index disclosed by the Economic Justice Institute | (2259) |

| (3) | Exclude companies that cannot obtain financial data from FnGuide database | (28) |

| Final sample | 1929 |

| Cash Flows | FLC Stage | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction | Growth | Mature | Shake-Out | Shake-Out | Shake-Out | Decline | Decline | |

| Operating | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | - |

| Investing | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | + |

| Financing | + | + | - | - | + | - | + | - |

| Panel A. Descriptive on Full Sample | |||||||||

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Quartile | Max | ||||

| 25% | Median | 75% | |||||||

| CFP | 0.043 | 0.047 | −0.424 | 0.019 | 0.038 | 0.063 | 0.604 | ||

| NW | 4.126 | 0.049 | 3.944 | 4.094 | 4.127 | 4.160 | 4.279 | ||

| SW | 12.133 | 0.634 | 9.966 | 11.724 | 12.166 | 12.568 | 14.408 | ||

| SIZE | 26.692 | 1.315 | 23.224 | 25.830 | 26.510 | 27.289 | 32.731 | ||

| GRW | 0.046 | 0.316 | −0.731 | −0.049 | 0.023 | 0.100 | 6.805 | ||

| LEV | 0.385 | 0.187 | 0.001 | 0.236 | 0.382 | 0.535 | 0.958 | ||

| RND | 0.006 | 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.105 | ||

| Panel B. Difference Tests of Variables by FLC Stages and Chaebol | |||||||||

| Variable | CFP | NW | SW | ||||||

| Chaebol | Yes | No | t-Value | Yes | No | t-Value | Yes | No | t-Value |

| All | 0.043 (457) | 0.044 (1472) | −0.36 | 4.122 (457) | 4.127 (1472) | −1.85 * | 12.027 (457) | 12.168 (1472) | −4.47 *** |

| Introduction | 0.031 (27) | 0.024 (96) | 1.10 | 4.106 (27) | 4.127 (96) | −2.14 ** | 11.916 (27) | 12.146 (96) | −1.89 * |

| Growth | 0.038 (123) | 0.039 (365) | −0.16 | 4.137 (123) | 4.148 (365) | −1.12 | 12.167 (123) | 12.218 (365) | −0.80 |

| Mature | 0.048 (257) | 0.051 (765) | −0.97 | 4.121 (257) | 4.129 (765) | −2.32 ** | 11.994 (257) | 12.194 (765) | −4.32 *** |

| Shake-out | 0.039 (40) | 0.039 (209) | −0.34 | 4.103 (40) | 4.115 (209) | −1.36 | 11.860 (40) | 12.027 (209) | −1.53 |

| Decline | 0.027 (10) | 0.028 (37) | −0.94 | 4.096 (10) | 4.118 (37) | −1.49 | 11.675 (10) | 12.009 (37) | −1.69 * |

| Variable | CFP | NW | SW | SIZE | GRW | LEV | RND |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFP | 1.000 | ||||||

| NW | 0.211 *** | 1.000 | |||||

| SW | 0.182 *** | 0.924 *** | 1.000 | ||||

| SIZE | 0.024 | 0.147 *** | 0.077 ** | 1.000 | |||

| GRW | 0.077 *** | 0.063 *** | 0.068 *** | −0.011 | 1.000 | ||

| LEV | −0.268 *** | −0.094 *** | −0.115 *** | 0.190 *** | 0.054 ** | 1.000 | |

| RND | 0.070 *** | 0.256 *** | 0.250 *** | 0.060 *** | 0.062 *** | −0.047 ** | 1.000 |

| FLC | All | Chaebol | Non-Chaebol | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NW–CFP | SW–CFP | N | NW–CFP | SW–CFP | N | NW–CFP | SW–CFP | N | |

| Introduction | 0.108 | 0.103 | 123 | 0.122 | 0.125 | 27 | 0.142 | 0.130 | 96 |

| Growth | 0.180 *** | 0.169 *** | 488 | 0.279 *** | 0.280 *** | 123 | 0.149 *** | 0.132 ** | 365 |

| Mature | 0.263 *** | 0.223 *** | 1022 | 0.253 *** | 0.218 *** | 257 | 0.269 *** | 0.227 *** | 765 |

| Shake-out | 0.140 ** | 0.104 * | 249 | 0.147 | 0.176 | 40 | 0.145 ** | 0.097 | 209 |

| Decline | 0.085 | 0.101 | 47 | 0.321 | 0.370 | 10 | 0.034 | 0.038 | 37 |

| Panel A. NW as CSP Measure | ||||||

| CFP = α0 + β1NW + β2SIZE + β3GRW + β4LEV + β5RND + ∑IND + ∑IND + ε | ||||||

| Variables | Exp. Sign | All | FLC Stage | |||

| Introduction | Growth | Mature | Shake-Out | |||

| Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | ||

| NW | +/− | 0.156 (6.859) *** | 0.036 (0.502) | 0.146 (3.540) *** | 0.202 (6.754) *** | 0.107 (1.303) |

| SIZE

| + | 0.002 (2.328) *** | 0.006 (2.114) ** | 0.002 (1.393) | 0.002 (1.303) | −0.004 (−0.904) |

| GRW

| + | 0.013 (3.738) *** | 0.026 (1.859) * | 0.029 (4.233) *** | 0.009 (2.193) ** | 0.006 (0.441) |

| LEV

| − | −0.068 (−11.785) *** | −0.049 (−2.598) ** | −0.066 (−5.863) *** | −0.075 (−9.618) *** | −0.026 (−1.283) |

| RND

| + | −0.011 (−0.134) | −0.071 (−0.221) | −0.122 (−0.906) | −0.061 (−0.608) | 0.585 (1.713) * |

| Intercept | +/− | −0.618 (−6.669) *** | −0.241 (−0.811) | −0.570 (−3.368) *** | −0.780 (−6.510) *** | −0.328 (−0.959) |

| ID | +/− | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| YD | +/− | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R2 | 12.0% | 9.4% | 12.3% | 17.6% | 4.4% | |

| F-value | 12.969 *** | 1.578 * | 4.101 *** | 10.881 *** | 1.522 * | |

| H0: β1Gro = β1Mat | 27.925 *** | |||||

| N | 1929 | 123 | 488 | 1022 | 249 | |

| Panel B. SW as CSP Measure | ||||||

| CFP = α0 + β1SW + Controls + ε | ||||||

| Variables | Exp. Sign | All | FLC Stage | |||

| Introduction | Growth | Mature | Shake-Out | |||

| Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | ||

| SW | +/− | 0.009 (5.029) *** | 0.002 (0.321) | 0.009 (2.820) *** | 0.011 (4.700) *** | 0.005 (0.757) |

| Controls | +/− | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R2 | 11.0% | 9.3% | 11.4% | 15.7% | 3.9% | |

| F-value | 11.859 *** | 1.569 * | 3.859 *** | 9.614 *** | 1.463 * | |

| H0: β1Gro = β1Mat | 27.228 *** | |||||

| N | 1929 | 123 | 488 | 1022 | 249 | |

| Panel A. Chaebol Firms | |||||||

| Variables | Exp. Sign | Chaebol | FLC Stages | ||||

| Introduction | Growth | Mature | Shake-Out | ||||

| Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | |||

| NW

| +/− | 0.149 (4.309) *** | 0.035 (0.204) | 0.148 (1.999) ** | 0.158 (3.222) *** | 0.034 (0.236) | |

| SIZE

| + | 0.001 (0.905) | 0.005 (0.399) | 0.002 (0.778) | 0.001 (0.722) | 0.005 (0.554) | |

| GRW

| + | 0.024 (2.550) ** | 0.009 (0.102) | 0.026 (1.540) | 0.025 (1.880) * | 0.003 (0.057) | |

| LEV

| − | −0.064 (−6.440) *** | −0.175 (−2.190) * | −0.035 (−1.840) * | −0.069 (−4.903) *** | −0.018 (−0.287) | |

| RND

| + | 0.082 (0.469) | −0.538 (−0.284) | 0.595 (1.888) * | 0.144 (0.653) | 1.166 (0.212) | |

| Intercept

| +/− | −0.503 (−3.666) *** | 0.135 (0.218) | −0.489 (−1.533) | −0.532 (−2.799) *** | 0.295 (0.478) | |

| ID | +/− | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| YD | +/− | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Adjusted R2 | 21.7% | 2.7% | 34.0% | 23.3% | 2.3% | ||

| F-value | 6.757 *** | 1.708 * | 3.853 *** | 4.694 *** | 1.617 * | ||

| H0: β1Gro = β1Mat | 8.269 *** | ||||||

| N | 457 | 27 | 123 | 257 | 40 | ||

| Panel B. Non-Chaebol Firms | |||||||

| Variables | Exp. Sign | Non-Chaebol | FLC Stages | ||||

| Introduction | Growth | Mature | Shake-Out | ||||

| Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | |||

| NW

| +/− | 0.171 (5.871) *** | 0.098 (0.917) | 0.110 (2.187) ** | 0.249 (6.494) *** | 0.122 (1.152) | |

| Controls | +/− | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Adjusted R2 | 11.1% | 9.2% | 11.1% | 16.7% | 4.8% | ||

| F-value | 9.362 *** | 1.438 * | 3.064 *** | 7.973 *** | 1.480 * | ||

| H0: β1Gro = β1Mat | 19.427 *** | ||||||

| N | 1472 | 96 | 365 | 765 | 209 | ||

| Panel C. Moderating Effect of Chaebol Firms | |||||||

| CFP = α0 + β1CSP + β2Chaebol + β3CSP × Chaebol + Controls + ε | |||||||

| Variable | Exp. Sign | A11 | Growth | Mature | |||

| Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | ||

| NW

| + | 0.179 (6.61) *** | 0.141 (2.96) *** | 0.242 (6.82) *** | |||

| SW

| + | 0.011 (4.67) *** | 0.009 (2.28) ** | 0.014 (4.77) *** | |||

| Chaebol

| − | 0.004 (1.28) | 0.004 (1.29) | 0.001 (0.16) | 0.003 (0.34) | 0.003 (0.74) | 0.003 (0.64) |

| NW ×

Chaebol | +/− | −0.060 (−1.34) | 0.017 (0.19) | −0.109 (−1.92) * | |||

| SW ×

Chaebol | +/− | −0.002 (−0.53) | 0.003 (0.34) | −0.006 (−1.65) * | |||

| Controls | +/− | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R2 | 12.1% | 11.0% | 11.9% | 11.1% | 17.8% | 15.7% | |

| F-value | 12.052 *** | 10.956 *** | 3.746 *** | 3.535 *** | 10.190 *** | 8.918 *** | |

| N | 1929 | 1929 | 488 | 488 | 1022 | 1022 | |

| Panel A. 2SLS (Two-Stage Square) | |||||||||

| First Stage Equation: CSP = α0 + β1CFP + β2Pre_CSP + β3SIZE + ∑IND + ∑IND + ε Second Stage Equation: CFP = α0 + β1CSPHAT + β2SIZE + β3GRW + β4LEV + β5RND + ∑IND + ∑IND + ε | |||||||||

| Variable | Exp. Sign | The First Stage | The Second Stage | ||||||

| Estimate | (t-Value) | Estimate | (t-Value) | Estimate | (t-Value) | Estimate | (t-Value) | ||

| CFP | + | 0.101 | (3.86) *** | 0.939 | (2.97) *** | ||||

| Pre_NW | + | 0.468 | (18.15) *** | ||||||

| Pre_SW | + | 0.545 | (22.24) *** | ||||||

| NWHAT | + | 0.555 | (9.89) *** | ||||||

| SWHAT | + | 0.025 | (6.22) *** | ||||||

| SIZE | + | 0.003 | (2.31) ** | 0.013 | (1.09) | −0.001 | (−0.01) | 0.003 | (2.00) ** |

| GRW | + | 0.048 | (5.66) *** | 0.051 | (5.95) *** | ||||

| LEV | − | −0.069 | (−9.77) *** | −0.072 | (−9.94) *** | ||||

| RND | + | −0.111 | (−1.24) | −0.070 | (−0.75) | ||||

| Intercept | +/− | 2.119 | (20.20) *** | 5.432 | (13.57) *** | −2.201 | (−9.86) *** | −0.288 | (−5.49) *** |

| ID | +/− | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| YD | +/− | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 36.7% | 44.3% | 21.9% | 16.5% | |||||

| F-value | 36.196 *** | 49.191 *** | 15.136 *** | 11.815 *** | |||||

| Panel B. Growth vs. Mature | |||||||||

| CFP = α0 + β1CSPHAT + Controls + ε | |||||||||

| Variable | Exp. Sign | Growth | Mature | Growth | Mature | ||||

| Estimate | (t-Value) | Estimate | (t-Value) | Estimate | (t-Value) | Estimate | (t-Value) | ||

| NWHAT | + | 0.424 | (3.75) *** | 0.658 | (8.57) *** | ||||

| SWHAT | + | 0.016 | (1.91) * | 0.030 | (5.57) *** | ||||

| Controls | +/− | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 22.8% | 24.2% | 13.1% | 19.3% | |||||

| F-value | 3.619 *** | 10.807 *** | 3.008 *** | 8.341 *** | |||||

| H0: β1Gro = β1Mat | 13.489 *** | 16.028 *** | |||||||

| N | 488 | 1022 | 488 | 1022 | |||||

| Panel C. Moderating Effect of Chaebol Firms | |||||||||

| CFP = α0 + β1CSPHAT + β2Chaebol + β3CSPHAT × Chaebol + Controls + ε | |||||||||

| Variable | Exp. Sign | All | Growth | Mature | |||||

| Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | Estimate (t-Value) | ||||

| NWHAT

| + | 0.562 (9.99) *** | 0.424 (3.76) *** | 0.666 (8.67) *** | |||||

| SWHAT

| + | 0.028 (6.16) *** | 0.013 (1.38) | 0.036 (5.87) *** | |||||

| Chaebol

| − | 0.004 (1.28) | 0.086 (1.09) | −0.003 (−0.22) | −0.125 (−0.83) | −0.003 (−0.25) | −0.003 (−0.32) | ||

| NWHAT ×

Chaebol | +/− | −0.001 (−0.87) | 0.002 (1.12) | −0.001 (−1.95) ** | |||||

| SWHAT ×

Chaebol | +/− | −0.007 (−1.01) | 0.011 (0.88) | −0.016 (−1.79) * | |||||

| Controls | +/− | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 20.6% | 16.6% | 16.6% | 13.2% | 24.2% | 19.5% | |||

| F-value | 14.612 *** | 10.973 *** | 3.516 *** | 2.842 *** | 10.355 *** | 7.811 *** | |||

| N | 1929 | 1929 | 488 | 488 | 1022 | 1022 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, B.-J. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: The Role of Firm Life Cycle in Business Groups. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7445. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137445

Park B-J. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: The Role of Firm Life Cycle in Business Groups. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7445. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137445

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Bum-Jin. 2021. "Corporate Social and Financial Performance: The Role of Firm Life Cycle in Business Groups" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7445. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137445

APA StylePark, B.-J. (2021). Corporate Social and Financial Performance: The Role of Firm Life Cycle in Business Groups. Sustainability, 13(13), 7445. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137445