Abstract

Nature play with young children has been criticized for lacking the transformative power necessary for meaningfully contributing to sustainability issues. The purpose of this systematic review was to identify outcomes associated with young children’s nature play that align with Education for Sustainability outcomes, toward addressing the question of its contribution to a more sustainable future. A total of 272 citation records were screened using eligibility and quality appraisal criteria, resulting in 32 studies that were reviewed. These studies’ outcomes were coded and then mapped to an education for sustainability framework. Results suggest that nature play supports education for sustainability benchmarks of applied knowledge, dispositions, skills, and applications. The multiple and varied relevant outcomes associated with nature play suggest practitioners should not abandon nature play in the pursuit of sustainability. Implications for practice and further research are discussed.

1. Introduction

Early childhood is a critical period, not only in the in the context of development, but also in the context of sustainability, as values, attitudes, and foundational skills learned in early childhood extend throughout life. The importance of early childhood education for sustainability (ECEfS) is internationally recognized, yet differing approaches have been put forward to achieve its goals. One approach emphasizes time in nature, as exploratory and playful experiences in nature provide a foundation upon which children develop the attitudes and values they carry into adulthood. However, some researchers [1] have criticized this nature-oriented approach as an impediment to children’s ability to work for a sustainable future.

Consequently, another overarching perspective for ECEfS advocates for a more transformative, participatory orientation through honoring young children’s rights and responsibilities as agents of change and involving them in exploring worldviews, problem-posing, decision making, advocacy, and action. Davis and Elliott [1] (p. 1) urge researchers and practitioners to recognize the competences of young children as “thinkers, problem-solvers, and agents of change for sustainability.” They challenge traditional environmental learning notions of young children, suggesting the need for a transformative shift toward learning that encourages young children to engage in sustainability issues in authentic and meaningful ways—locally and in broader contexts.

Ernst and Burcak [2] pose a question that emerges from this diverging viewpoint: What contribution to sustainability is made through the pedagogical practice of nature play, or is a reorientation needed toward more critical and transformative pedagogies? This divergence was the backdrop for the systematic review at hand, which aimed to identify outcomes of young children’s nature play that are relevant and can contribute to a more sustainable future. Specifically, the following research question guided this systematic review: What is the contribution of nature play in the context of EfS?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Early Childhood Education for Sustainability

Not only do today’s global sustainability issues impact children’s present lives, but they will also do so through the foreseeable future. Since today’s children will inherit these sustainability challenges, it is important to prepare them with the foundational knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values to understand and respond to these challenges. Development of environmental values, attitudes, skills, and behaviors begin to develop early in childhood [3], and thus EfS is particularly relevant in the context of early childhood. Beyond early formation of attitudes and values, it is suggested that children can grasp both the idea of sustainability and understand how to act sustainably, even at a young age [4]. Early Childhood Education for Sustainability (ECEfS) is grounded in the recognition of young children’s awareness of sustainability issues and capability to engage with them [4,5,6,7]. Edwards and Cutter-Mackenzie [8] describe ECEfS as constructing understanding about environmental and sustainability content, as well as developing the skills for meeting the needs of future generations by peacefully living in the environment.

Because of the urgency of sustainability issues and due to children’s capabilities, as well as the contributions ECEfS can make toward child development and learning, several countries, such as Norway, Australia, and New Zealand, center EfS specifically in their early childhood curricula. Norway’s kindergarten curriculum includes themes of democracy, diversity, mutual respect, equality, sustainable development, life skills, and health. Additionally, for example, it states “the kindergarten has an important task to promote values, attitudes and practices for a more sustainable society… The kindergarten shall contribute to give children an understanding that [any] actions have consequences in the future” [9] (p. 10).

Other countries beyond Norway address ECEfS within their early childhood curricular frameworks. Weldemariam et al. [9] use the work of Ärlemalm-Hagsér and Davis [10] as a basis to further examine the national early childhood education frameworks of countries for their explicit or implicit inclusion of ECEfS and the underlying educational theories that inform the early childhood approaches in each country’s national curricula. Their review suggests countries vary in emphases and approaches as to the implementation of ECEfS in their respective culture and educational settings. Some countries focus primarily on the development of values and attitudes in ECEfS, while others focus on skills and/or knowledge. Others have a primary focus on early childhood development, with an inclusion of environmental/sustainability-related outcomes but not as an area of emphasis.

A consideration of underlying theories may help shed light on these differing approaches and emphases, as noted in Weldemariam et al. [9]. Sociocultural, social constructivist, and Piagetian developmental learning approaches commonly ground early childhood curricular frameworks. Yet, approaches that explore beyond the human, cognitive, and social worlds, such as post-humanism, have the potential to enable children to know and contribute to sustainability in a different context than how most countries approach EfS and ECEfS in established frameworks. This post-humanist approach calls for children as change agents and as active participants in democratic processes where children can engage in and respond to the world around them in ways that might not be expected when viewed through a lens limited by biological age and prescribed development stage. This can be perceived as counter to Piaget’s linear construct of cognitive growth and developmental stages based on biological age [11].

In the context of ECEfS, post-humanism is the recognition of the interconnections of humans and “more-than-humans” that share the earth [12]. This realignment shifts the focus from oppositional humans and nature to relational humans and nature [13]. Decentering humans from the social context places equitable value for all beings in the system. In doing so, humans are viewed as being entangled with and of nature rather than just in it [13], or what some scholars refer to as nature as extended self [14] or co-habitors of a shared planet [13]. Rather than viewing nature as something to be studied and cared for, and simply preparing children to be good stewards of the planet, EfS calls for a “beyond stewardship” relationship with the rest of the natural world [12].

Argent and colleagues [15] discuss how children can grasp a more-than-human perspective, and Griffiths and Murray [16] advocate for children to have opportunities to engage with building the world from their perspective of being a part of the world instead of separate from it. Early childhood education is well poised to embrace such perspectives and approaches with the relatively open nature of early years’ curriculum [9]. From a post-humanist perspective, it is acknowledged that children deserve ample opportunities to engage with the natural world to learn through play [17]. Should their agency move them to identify sustainability issues and work toward solutions, however, some theorists and practitioners feel we should not shield their perceived innocence on the basis of their biological age or assumed lack of knowledge, values, or skills. Nor should the perceived risks of complexity or hopelessness often associated with environmental issues be reason to limit children’s action for sustainability [18].

Consequently, it has been suggested that practitioners move away from more conventional learning theories and their subsequent pedagogies in exchange for embracing a more transformative approach to ECEfS where children are viewed as active change agents [19]. This transformative curriculum is seen as a holistic and co-created approach between children, teachers, and families featuring democratic processes, critical thinking, and engagement with the community [20]. While this approach has been predominantly embraced in Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, and some Scandinavian countries [1], it has not yet been widely adopted in the United States. The prevailing thinking in the United States is that early childhood years are the prime time to emphasize connection with nature. The concepts of EfS are often seen as beyond the scope of early childhood education, and there is a need to first ground children in positive experiences in the natural world. Expecting children to act on behalf of the environment in early childhood is generally avoided in the United States’ approach to ECEfS, as children should develop a love for the natural world before being asked to save it. Accordingly, nature-based experiences and pedagogies have been the more predominant approach for these reasons in the United States [21].

Underlying this approach is the premise that experiences in nature are the foundation upon which children develop the attitudes and values they carry into adulthood. Several studies describe the specific connection between time in nature and positive impacts on environmental values and attitudes throughout life [22,23,24]. While childhood nature experiences often link specific places with positive affection and affinity [22], it is also important to note that during the formative years, a deficit of experiences in nature can lead to adversity towards, fear of, and mistrust in natural spaces [25]. The experiences of loss of a special place have also been shown to have a long-term negative impact [22]. Additional sociocultural factors can further alienate children from nature including transfer of fears, disinterest, lack of opportunities, and implicit social messaging [26]. It is also important to note that while childhood experiences in nature are linked to adult values, attitudes, and behaviors, these experiences may not act as a singular catalyst [2]. However, is childhood nature play an impediment to sustainability, as suggested by Davis and Elliot [1]?

2.2. Nature Play as ECEfS

In the context of young children, nature play is set apart from other types of play in that it takes place in outdoor, natural settings; is unstructured or loosely structured; and involves interactions with nature (not just in nature) [27]. Nature play is also distinguished from more structured forms of nature-based learning and programming [27]. For children, playing is learning [28], and thus there are many benefits of nature play. Nature play is associated with significant benefits to children’s academic and social and emotional learning, as well as health benefits [29]. In addition, nature play has been associated with environmental learning outcomes, such as exploratory behaviors [30], stewardship [31], reflective thinking [32], and curiosity [2].

In spite of these outcomes, criticisms of nature play in the context of ECEfS exist, including the fact that educators may misalign exposure to naturalized outdoor play settings with fulfillment of ECEfS expectations [13]. Nature play advocates also have been criticized for their presumed rationale for nature play: EfS is too complex for children, and age and perceived innocence necessitate the use of nature play. Additionally, the point is made that inclusion of nature play impedes the practice, examination, and acceptance of effective techniques for ECEfS [33].

In light of these criticisms, it may be helpful to be reminded of Edwards and Cutter-MacKenzie’s [8] description of ECEfS as constructing understanding about environmental and sustainability content as well as developing the skills for meeting the needs of future generations. Nature play shows potential for teaching about sustainability, particularly when purposefully framed and guided toward environmental understandings. Education about sustainability, however, is not enough to foster the values, attitudes, and skills learners need to act for a sustainable future [8,34].

Nature play has the potential to build skills, attitudes, and values associated with education for sustainability, evidenced by studies mentioned prior. ECEfS in the form of unstructured nature play can support children’s natural tendencies to embrace the more-than-human world [21]. While nature play sometimes has been reduced to “exposure to nature or naturalized surroundings”, it is often more than that, including children having formative experiences, reflecting on their learning, and being transformed as a result of their interactions with the natural setting. Thus, the pedagogy of play is worth examining as an approach for building skills and dispositions identified as essential to EfS.

Another criticism of nature play stems from the lack of prominence of the role of the teacher. Critics point out teachers are essential to children’s learning, and without making learning explicit, children would not be aware of the concepts or ECEfS or achieve the outcomes of ECEfS [17]. Fleer [35] similarly posits that children need adults to assist them in accessing the knowledge conveyed through place [8]. Thus, sustainability concepts are unlikely to be learned by children solely through nature play [8].

These criticisms of nature play further underscore varying perspectives as to how and if nature play contributes to sustainability. Thus, the context for the review at hand is this very question of nature play’s contribution to sustainability that is spurring an international call for more critical and transformative approaches to ECEfS, including the adoption of pedagogies such as advocacy and action-taking in sustainability issues locally and more broadly.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Purpose

The purpose of this study was to identify outcomes of young children’s nature play that can contribute to a more sustainable future. The aim was not to further categorize or emphasize differences across different types of nature play approaches and programs, nor was it to evaluate the effectiveness of nature play programs or link specific program characteristics to outcomes. Instead, the review sought to identify outcomes that are associated with nature play with young children that align with EfS outcomes, toward addressing the question of its contribution in the context of EfS. Thus, the overarching methodology can be thought of in terms of two general phases: (1) the systematic review, which yielded outcomes associated with young children’s nature play, and (2) the mapping of these outcomes to an established framework of EfS outcomes.

3.2. Systematic Review Design and Search Process

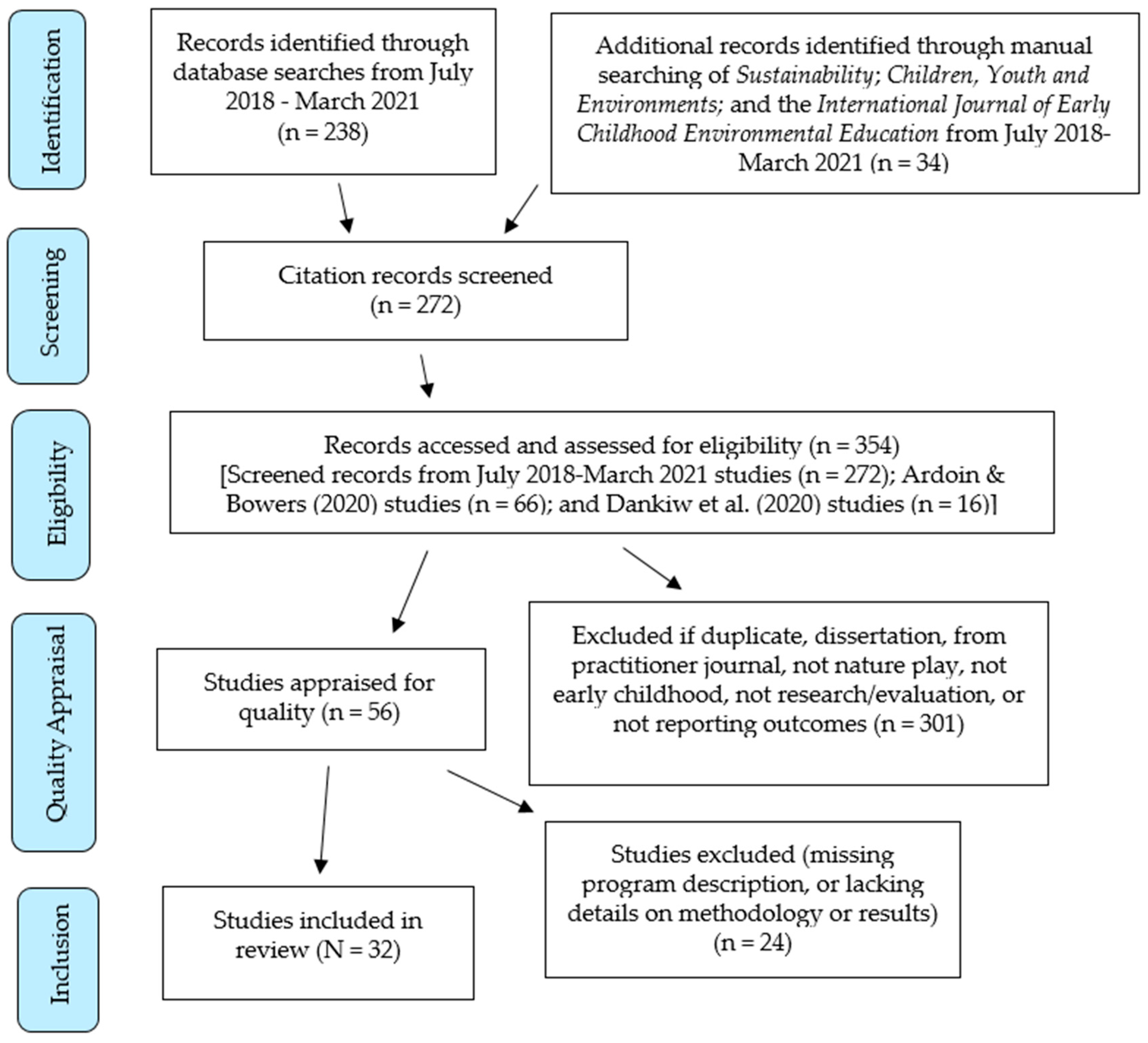

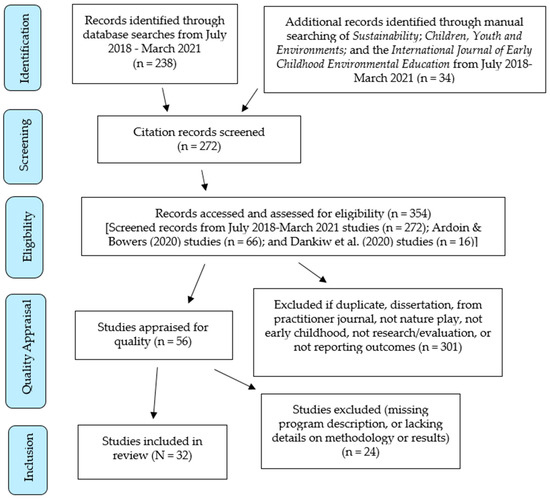

In general, the methodology for the systematic review followed the process used by Ardoin and Bowers [36] in their review of outcomes of early childhood environmental education. Their methodology was modeled after PRISMA and its criteria for conducting and reporting systematic reviews [37]. This process entails the general steps of identifying records using search terms, initial screening of records, reviewing records for eligibility, and reviewing and synthesizing the resulting studies that were eligible for inclusion in the review. See Figure 1 for a summary of this process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram based on Moher et al. [37] and exclusion criteria guided by Ardoin and Bowers [36].

The review of Dankiw et al. (2020) included studies published through July 2018, and Ardoin and Bowers [27] included studies published through December 2018. Databases used in Ardoin and Bowers’s [36] review of early childhood environmental education program outcomes and Dankiw et al.’s [27] review of unstructured nature play outcomes were used to identify studies published since the timeframe of their reviews, which was the time period from July 2018 through to the end of March 2021.

Across their two reviews, the following academic databases had been used: Academic Search Premier, Africa-Wide Information, British Education Index, Education Full Text, Embase, Emcare, Environment Index, ERIC, GreenFILE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, The Cochrane Library, and The Joanna Briggs Institute. However, the research team for this systematic review at hand did not have institutional library access to several of the databases (Africa-Wide Information, British Education Index, Education Full Text, Embase, Emcare, Environment Index, and The Joanna Briggs Institute). Three databases were substituted where access was limited or not possible: Education Research Complete was substituted for Education Full Text, Agriculture and Environmental Collection was substituted for Environment Index, and Academic Search Ultimate was substituted for Academic Search Premier. MEDLINE and The Cochrane Library, being medical databases, did not yield articles related to our nature play search terms. Thus, the following databases were searched to identify articles published since July 2018 through March 2021: Academic Search Ultimate, Agriculture and Environmental Science Collection, Education Research Complete, ERIC, GreenFILE, and PsycINFO.

Ardoin and Bowers [36] also used manual searching of Children, Youth and Environments and the International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education, as articles in these two publications did not consistently appear in database searches. Thus, these two journals were also included in this step. The journal Sustainability was also manually searched to identify studies related to our search terms published between July 2018 and March 2021, in light of their inclusion of EfS and ECEfS articles.

To identify records, we used the following search terms, which were drawn from the two aforementioned systematic reviews: preschool, kindergarten, free play, forest school, childcare, day care, early childhood, early elementary, early primary, nursery school, primary grade, toddler, young child, young children, education for sustainability, education for sustainable development, environmental education, forest kindergarten, nature preschool, nature-based preschool, and sustainability education. The terms used by Dankiw et al. [27] and Ardoin and Bowers [36] that were less specific (forest, nature, natural, outside, outdoors, play, green school, green space, childcare, outdoor classroom) were removed from the search terms list, as preliminary searches yield hundreds of thousands of articles meeting the initial search criteria. The following additional specific search terms were included in this review to further focus and yield relevant articles for the specific purpose at hand: early childhood education, early years, nature play, nature kindergarten, forest preschool, outdoor play, and early childhood education for sustainability.

The database searches identified a total of 238 citation records after duplicates were removed, and the manual searches of the three journals identified an additional 34 unique citation records. The combined results from both of these search strategies yielded a total of 272 citation records for this study identification step.

3.3. Study Screening and Eligibility

The inclusion criteria for the systematic literature review at hand were as follows: studies that focused on young children aged from birth through to age eight, reported outcomes for a program that was described as and/or used nature play, and those that were designed as empirical research or evaluation. Exclusion criteria were drawn from Ardoin and Bowers [36]: studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria, articles that were in practitioner-oriented journals (that tend to describe classroom activities or include lesson plans), studies that were in the form of dissertations or conference papers/abstracts, and textbooks or book chapters.

The studies from the two completed systematic reviews (n = 66 and n = 16), along with the 272 eligible studies identified from the database searches from July 2018 to March 2021, resulted in a sample of 354 studies that moved forward into the next step of the systematic review process. Patterning after the approach used by Ardoin and Bowers [36], the abstracts of the 272 records (from July 2018 to March 2021) were screened using the above exclusion criteria. The abstracts of the 66 studies from Ardoin and Bowers [36] and the 16 studies from Dankiw et al. [27] were also reviewed for eligibility against the inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria. This was necessary, as Ardoin and Bowers [36] focused on environmental education programs in the context of early childhood, which includes but is not limited to nature play. Similarly, while Dankiw et al. [27] focused on nature play, their review included studies of children ranging in ages up to age 12, which exceeded the early childhood period of birth through age eight.

A total of 301 records were excluded through the eligibility screening process. The full-text articles for the remaining 56 records were then located and further reviewed to ensure they met the inclusion criteria.

3.4. Quality Appraisal

The criteria used for the quality appraisal were drawn from Ardoin and Bowers [36]. The criteria were as follows: peer-reviewed research, including a program description, including information on the research methods and data, and the findings needed to be sufficiently detailed. Fifty-six studies were reviewed using these criteria, with 24 studies not meeting these criteria. Thus, there were 32 studies that moved forward in the process for inclusion in the review.

3.5. Data Analysis

The data analysis step was undertaken using the final set of 32 studies, which were published during the time period of January 1995 to March 2021 and met the criteria from the preceding steps. A spreadsheet was created and used to record the following information for each of the 32 studies included in the review: authors and publication date, location of study (country), age of program participants, program description, research methodology, and summary of study outcomes. In the initial review, the reported outcomes from each study were recorded but not coded. Additionally, if findings were null or negative, this was noted on the spreadsheet.

Then, each study’s reported outcomes were coded on the spreadsheet using categories adapted from Ardoin and Bowers [36], as well as from the North American Association for Environmental Education Framework for Assessing Environmental Literacy [38], early childhood learning domain descriptions from the Minnesota Early Childhood Indicators of Progress [39], and the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University [40]. See Table A1 (Appendix A) for a listing of the outcome categories, a description of each, and their source.

These outcome categories were used again in the next step of the coding process, where all of the specific outcomes within any one outcome category were reviewed to check for internal consistency and conceptual coherence as a category of outcomes. Two researchers were involved in this process of reviewing studies and recording information on the spreadsheet, coding articles according to outcome categories, and reviewing the coding for consistency and coherence. Researchers first worked independently and then reviewed the resulting coding and category sets. Inconsistencies or discrepancies were discussed, and the study was re-reviewed, toward agreement on finalized coding.

The next step of the data analysis process involved aligning the study outcomes with the ECEfS outcomes by mapping them to ECEfS outcomes. This alignment/mapping was conducted using two guiding documents for EfS, the Cloud Institute’s Education for a Sustainable Future Benchmarks for Individual and Social Learning [41], which is for all ages, and secondly, a related document specifically designed for ECEfS, the Cloud Institute’s Education for a Sustainable Future Standards and Performance Indicators PreK-2 Edition [42], which is a more narrow set of content standards/applied knowledge standards than in Cloud Institute’s Education for a Sustainable Future Benchmarks for Individual and Social Learning The outcome categories and corresponding specific outcomes from the 32 studies were mapped against the benchmarks and standards in these two guiding documents by one of the researchers, with a second researcher reviewing and confirming the mapped outcomes, and a final review of the coding and mapping by two additional researchers. Discrepancies were discussed toward reaching agreement on this mapping process. While the performance indicators were helpful in the mapping process in terms of conveying the meaning of the specific standard at hand, the nature play outcomes were mapped to the standards, not the performance indicators.

4. Results

Of the 32 studies reviewed, 15 were studies from the United States, six were from Canada, four were from Turkey, three were from the United Kingdom, two were from Australia, one was from Greece, and one study was from Hong Kong. Most of the studies (22 of 32) were conducted with preschool- and/or kindergarten-aged children (typically ages three to five years old), with five studies that included participants younger than three years old, and two studies that included children up to age eight. Many of the studies (14 of 32) used qualitative methods, 12 used quantitative methods, and 6 used mixed methods in their research methodology. While all of the programs studied included and emphasized nature play, the range of contexts and settings varied. Many of the studies were of nature preschools or forest kindergartens. Others were nature play integrated within early childhood education centers/program through the help of a community partner such a nature center, park, or wildlife sanctuary. Some of these programs were traditional childcare, preschool, or kindergarten classes (including several located at universities or in urban areas) that were incorporating trips to local natural areas into their curriculum toward the provision of nature play opportunities. Others were adapting their onsite facilities to include naturalized spaces. The studies collectively displayed a wide array of positive outcomes across many domains. Table A2 summarizes the 32 studies reviewed, including each study’s location, program description, age of participants, research methodology, and reported outcomes.

There were 98 total outcomes of nature play reported by the 32 studies. The most frequently reported outcomes across all the studies were connection to nature; stewardship of plants, wildlife, living things, and nature/compassionate care for nature; self-confidence; and self-regulation/self-management/self-control, each with six separate studies reporting these as outcomes. Five different studies reported prosocial skills and behaviors, and exploratory skills was also reported in five studies as an outcome of nature play. Fourteen other outcomes of nature play were each reported four or more times across the 32 studies, and 27 outcomes had three or more mentions across the studies. Table A3 displays the results of coding the study outcomes into the outcome categories. The outcome categories that represented the most examples of evidence were social and emotional development (18 different examples of reported outcome evidence), cognitive: scientific knowledge and thinking (12 examples), and approaches to learning (12 examples).

The second step of the analysis involved mapping the outcomes from the 32 studies to the ECEfS guiding documents [41,42] (see Table A4). Regarding the benchmark applied knowledge, there was evidence from the reviewed nature play studies for most of the standards, including the following: cultural preservation and transformation, responsible local and global citizenship, the dynamics of systems and change, inventing and affecting the future, multiple perspectives, and strong sense of place. Of these, responsible local and global citizenship, inventing and affecting the future, and strong sense of place had the greatest breadth and quantity of supporting studies. Three of the standards within the applied knowledge benchmark did not have evidence from nature play studies reviewed: sustainable economics, healthy commons, and natural laws and ecological principles.

Regarding the benchmark dispositions, both standards (being and relating) had supporting evidence from nature play studies, and both were mapped to a wide range of nature play outcomes and associated studies (see Table A4). The same was true for the benchmark skills, with the standards of thinking skills and hands-on skills both having a breadth and quantity of evidence from nature play studies, as shown in Table A4. Finally, the applications and actions benchmark had supporting evidence from nature play studies for all if its standards, including the following: build capacity, design and create, lead and govern, be just and fair, and participate and collaborate (see Table A4). Table A5 provides an overall summary representing the ECEfS benchmarks and standards and the respective supporting evidence of outcomes attained through nature play.

While many outcomes from the 32 nature play studies included in this systematic review did align with the ECEfS outcomes, there were some outcomes that did not. These include the outcomes in the categories of physical development outcomes and mental well-being. Moreover, the specific outcomes of self-expression, self-care, self-regulation, management, and control; early literacy and early numeracy; and skills for being in, moving in, and interacting with nature; confidence in nature; trust in and of nature; and autonomy did not directly align with ECEfS benchmarks, standards, or performance indicators.

5. Discussion

The backdrop for this study was the question that emerged from diverging viewpoints regarding ECEfS pedagogies: What contribution to sustainability is made through the pedagogical practice of nature play, or is a reorientation of the nature play movement needed toward more critical and transformative pedagogies [2]? Thus, the systematic review at hand sought to identify outcomes of young children’s nature play that further the aims of EfS.

First, though, it is important to acknowledge limitations to this review so that the results can be interpreted in the context of these limitations. While the intent was to use the same databases as used in the two prior systematic reviews of nature play and early childhood EE, not all of the databases were accessible through our associated universities, and thus substitutions were made. Moreover, researchers of nature play studies may have published in other journals that weren’t among those searched in this review. Consequently, there may be more evidence (more alignment) than what the results of this study suggest.

Alternatively, there may be less evidence (less alignment) than what the results of this study suggest, due to the criteria used in the quality appraisal step, which had been drawn from Ardoin and Bowers [36]. To be included in the review, the study had to be peer-reviewed research and include sufficiently detailed information on the research methods and data, and the findings needed to be sufficiently detailed. Applying these criteria, however, was more challenging than anticipated. Additionally, varying levels of rigor and internal and external validity were not fully accounted for through this appraisal, and thus from one study to another, the evidence may not be equally strong. Also challenging was the inclusion criteria that specified the study needed to be of nature play. Some of the studies were of programs that had nature play but had additional components as well. The extent to which programs had components beyond nature play was not accounted for in the review and analysis. Moreover, the mapping of nature play outcomes to the ECEfS framework was somewhat subjective, particularly as to the degree of relevance needed in order for the outcome to be mapped. Other researchers may have mapped them differently or more/less extensively. Finally, it is important to note that this review process was not to designed to enable identifying which standards were most or least supported through nature play, as the number of supporting studies mapped to any one standard in the framework does not necessarily suggest quantity of evidence, but potentially instead the breadth of the standard and/or the breadth (level of specificity) of the nature play outcome itself.

However, in spite of these limitations and on the basis of the results of the review, the answer to the question of nature play’s contribution to sustainability is both extensive and rich. In addition to evidence suggesting nature play is supporting the development of children across domains as well as the development of environmental literacy, the results of this review illustrate the many ways in which outcomes associated with nature play are relevant to EfS and ultimately a more sustainable future. Nature play appears to be contributing to applied knowledge in the context of sustainability, specifically cultural preservation and transformation, responsible local and global citizenship, the dynamics of systems and change, inventing and affecting the future, multiple perspectives, and strong sense of place. Nature play also appears to be contributing to sustainability aims by furthering the dispositions of being and relating. In addition, nature play is contributing thinking skills and hands-on skills, as well as contributing to the applications and actions of building capacity, designing and creating, leading and governing, being just and fair, and participating and collaborating. Not only was there alignment, there also was more alignment than what was anticipated, as well as unexpected alignment. There also were many interconnections, as opposed to one-to-one mapping, with multiple studies and associated outcomes mapping to more than one standard in the ECEfS framework.

While the question of nature play’s contribution to sustainability was the emphasis of the review, the results prompt another relevant question: Is nature play sufficient as a pedagogy for EfS with young children? While most of the ECEfS standards were mapped to nature play studies, and thus could be considered supported through nature play, several within the applied knowledge benchmark were not: sustainable economics, healthy commons, natural laws, and ecological principles. Additionally, while most standards had associated outcomes from nature play studies, for manageability and feasibility, mapping was done at the level of the standards as opposed to the level of the performance indicators. Thus, within any one standard, it is likely that the complete set of performance indicators did not have accompanying evidence of being achieved through nature play, and thus the standard would likely not be met in its entirety solely through nature play. That is not to say it could not be, but that there is not existing research evidence from the review at hand (it may exist but did not surface in this review, or it perhaps could be happening through nature play, but not yet assessed through research). Thus, it would be appropriate to suggest that nature play may not be (or is not yet known to be) sufficient toward meeting all of the desired outcomes of ECEfS.

Additionally, the response to these questions of nature play’s contribution to sustainability and the sufficiency of nature play as a pedagogical approach for ECEfS depends on the framework used. The ECEfS outcomes used in this review, drawn from Cloud [41,42], somewhat mirrored the outcome domains of environmental literacy (knowledge, attitudes, skills, actions/behaviors): applied knowledge, dispositions, skills, applications, and actions. However, just as there is not yet a universally shared understanding of “sustainability”, [41], there also is not a universally shared understanding of the aims of EfS.

Thus, whether nature play contributes to sustainability, and the extent to which it does so, depends on the framing of sustainability and on the EfS framework used. If, for example, Australia’s Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework had been used, the mapping (and thus level of sufficiency) would differ from what surfaced through the review and mapping at hand. As described by Elliott [43], children are not only belonging, being, and becoming in their sociocultural systems, but with respect to the earth’s systems. Thus, their framework allows for a biocentric rather than a solely human-centered interpretation of what it means to belong, be, and become (and consequently, their early childhood benchmarks in essence are one in the same as the ECEfS benchmarks). In Elliott’s [43] description of ECEfS outcomes, it is clear how relevant nature play can be as a strategy for EfS, especially in light of the outcomes that surfaced through this review of nature play research:

…children need opportunities to experience relationships of belonging with nature and construct understandings about the complex dynamic interdependencies between humans and the Earth. Being is fully experiencing the here and now and natural elements offer children sensory-rich opportunities for being in the moment, while Becoming is about a process of change, children becoming active and empowered participants for sustainability in a rapidly changing climate.[33] (para 7)

The question of the extent to which nature play contributes, or nature play’s sufficiency as a pedagogical approach in the context of ECEfS, also leads to the question of whether or not nature play needs to be sufficient. Does nature play need to be the sole pedagogy in order to be considered valid in the context of society’s quest for sustainability? A somewhat parallel question is raised in science education and in the context of young children. This introductory text precedes the early learning standards in the domain of scientific thinking for Minnesota’s (United States) Early Indicators of Child Progress [39]:

The indicators in the Scientific Thinking domain … reflect the new thinking in the science education field: that for young learners, scientific inquiry is more beneficial than occasional and unconnected science activities. Therefore, the focus for this domain is on scientific processes more than specific science content with the idea that this approach will lay the foundation for developing ways of thinking that support more rigorous academic study in the Scientific Thinking domain in the elementary school years.[44] (p. 1)

Accordingly, it could be argued that the inquiry and exploration arising naturally in the context of nature play might be more beneficial than unconnected, content-focused activities that are aimed to toward building sustainability-related knowledge, or action-oriented activities that lack a meaningful connection to children’s spheres of experiences. Conceivably, nature play is laying the foundation for developing ways of thinking (and ways of being and relating) that support more rigorous learning in the school years and beyond. This should not be seen as problematic, nor as a fault or as a source of criticism, as seldom if ever is there one sole pedagogy, practice, or program that supports learners toward competency across an entire set of benchmarks and standards that does not take away from nature play’s value. Nature play can be used alongside other pedagogies, as well as serve as the foundation for the scaffolding of other sustainability experiences as children grow.

This sentiment is consistent with Green [45] (p. 317), who writes, “a child does not learn how to run before discovering how to coordinate his feet to take his first steps”. Even Elliot [33], who has advocated for ECEfS pedagogies that are more transformative than nature play, states children need opportunities to experience relationships of belonging with nature, which this review of nature play outcomes certainly demonstrates. Elliot also notes the importance of children “being”, where they are able to be fully present as they experience nature through sensory-rich opportunities, which also happens in nature play.

It seems through being in nature and developing a sense of belonging, the becoming becomes possible. Elliot [33] describes becoming as a process of change, where children becoming active and empowered participants for sustainability in the midst of our rapidly changing climate. The results of this review suggest nature play is facilitating action, as children were actively participating in ways such as demonstrating respectful interactions with and compassionate and care toward other living creatures, teaching others about plants and animals, and encouraging their families to adopt environmental behaviors modeled in their nature preschools/play environments. While these actions are likely not the transformative actions for which Elliot and others advocate [1], Green’s [45] indication of the meaningfulness of these smaller-scale actions within children’s immediate sphere seems quite relevant: “It is important to consider the significance of children’s initial efforts as these provide stepping-stones to bigger and wider-reaching initiatives…making a difference at a smaller level will have an impact on how a child develops his or her sense of self in relation to the living world.” Thus, not only does this underscore the relevance of these actions that may not seem very transformative, perhaps this also suggests that the belonging and being are not only steps toward becoming, but also that the becoming might further the sense of belonging in nature.

6. Implications

6.1. Implications for Practice

While this systematic review was useful toward recognizing the many and varied contributions of nature play in the context of sustainability, the review and process of mapping nature play outcomes to the ECEfS framework also provides guidance for practice and research. Regarding implications for practice, Spearman and Eckhoff [46] suggest considering sustainability at a scale that is accessible to children, framed as “little ‘s’ sustainability”, in a place-based and local, community and systems context. It seems evident from the results of this review that nature play provides a context that makes sustainability not only accessible to young children, but also meaningful in terms of contributing to “big ‘S’ Sustainability”. Consequently, early childhood practitioners should not abandon nature play in the pursuit of sustainability.

With that said, an awareness of the range of performance indicators embedded with the ECEfS benchmarks and standards may open up new opportunities for practitioners to further deepen or broaden nature play and the conversations and explorations it naturally sparks. Edwards and Cutter-Mackenzie [8] refer to purposefully framed play that stems from observations of children’s play; conceivably, it could also stem from particular indicators or standards from the ECEfS framework. They also propose teacher-enhanced approaches to nature play, whereby teachers augment nature play with more direct instruction on sustainability concepts, toward explicit connections between experience and content [8]. Ultimately, however, sustainability is, in principle, inclusive of multiple ways of knowing and encouraging of multiple pathways to achieve environmental, societal, and economic prosperity. As Wilson [21] suggests, there does not need to be a choice between “saving” and “savoring” nature. Pearson and Degotardi [47] promote inclusive ECEfS, which embraces broad and diverse values and practices across global, sociocultural context as an embodiment of the best practices of EfS [21].

6.2. Implications for Research

The range of performance indicators, standards, and benchmarks within the ECEfS framework used in this systematic review also opens up possibilities for new research directions. While many of these already have supporting evidence, some have not yet been studied directly. Knowing what evidence exists provides an opportunity to further consider that evidence toward determining if additional or more rigorous evidence may be needed, and gaps in the framework signal where research is needed to determine nature play’s impact. Collectively, this can aid in our understanding of what nature play can and cannot offer in the context of sustainability so that other pedagogies can be drawn from and used as children grow toward an enduring kinship with nature, as well as toward an ever-deepening and ongoing participation in visioning, creating, and engaging in a healthy and just present and future.

A specific area for further research is regarding several interwoven criticisms of nature play (see [21] for an extended discussion). One is that nature play is not as relationship-oriented as EfS. Yet, evidence from this review suggests nature play is quite relationship-oriented, as there were many nature play studies mapped to the ECEfS standard of relating. Another criticism is that nature play promotes a view of nature as something separate from humans—something to be studied, experienced, and cared for, as opposed to a post-humanism orientation that aims for seeing “nature as extended self”, co-habiting a shared planet and being entangled with and of nature, not just in nature (as in [13,14,15]). While a number of nature play studies yielded outcomes suggesting that nature play was associated with actions of caring for nature, there also were many studies suggesting it was not only furthering children’s connection to nature, but also their environmental identities, feelings of belonging, and even a sense of intimacy and at home-ness in nature.

As noted prior, Green [45] suggests caretaking and stewardship actions that make a difference at a smaller level will have an impact on how a child develops their sense of self in relation to the living world. Thus, potentially rather than stewardship furthering the divide between nature and humans and prompting the need for pedagogies other than nature play to support a “beyond-stewardship relationship with nature” [12], perhaps stewardship is actually furthering children’s feelings of belonging in and to nature, as well as their understandings of being part of it. If this is translated into human contexts, this possibility seems plausible; deep and extended care for a family member, for example, does not necessarily lead to a widening gap between the caregiver and family member but can and often does lead to feelings of deepened connection and an extension of self. Thus further research is needed to better understand the possibility of stewardship coexisting with a cognitive and affective sense of oneness within nature and a recognition of the interdependence between people and the more-than-human world, or if instead stewardship and nature play more broadly contribute to a dualism that places “humans strictly outside the natural world of which they are a part of, and may thereby inadvertently perpetuate the very alienation it seeks to overcome” [48] (p. 109).

Related to this, further research might also investigate the suggestion that in addition to unstructured play in nature, children need opportunities to participate in re-making the world, on the basis of the understanding that they are a part of—rather than separate from—that world [16], as well as experiences that extend their caring beyond their individual interests and concerns [4], which is where social justice begins [16]. The review at hand, on the contrary, suggests nature play was affording opportunities for children to demonstrate caring and collaborative helping behaviors; children’s display of empathy and a sense of compassion, concern, and responsibility for others suggests they already were participating in re-making the world through interactions that furthered a sense of community and belonging that extended beyond their individual interests. Thus, further research might seek to understand the role of nature play in not only fostering caring and participation and as a mechanism toward social justice, but also if those behaviors are rooted in and/or furthering feelings of being part of versus separate from the world. Additionally, research might also investigate the transferability of outcomes such as empathy, compassion, and care across human and more-than-human nature contexts, or the potential for these dispositions and behaviors to be mutually reinforcing of a blurred boundary between humans and nature, where compassion and empathy, for example, toward other humans actually entails compassion and empathy with nature and vice versa.

7. Conclusions

The results of this review suggest nature play is a valid contributor to sustainability outcomes, and thus it should be acknowledged and embraced as an effective EfS approach with numerous, wide ranging benefits to young children. The use of a variety of pedagogies across the span of a child’s educational years can provide the experiences, content, and applications that can be drawn upon, individually and collectively, to create a sustainable future. Nature play is a good match for the early childhood years when children are developing skills and abilities across multiple domains. In addition to the strong physical, social, and cognitive outcomes afforded though nature play, children are gaining knowledge, skills, dispositions, and actions that are foundational to sustainability, and in many cases, these outcomes overlap. Thus, integrating sustainability and early childhood education represents what Wilson [21,49] describes as a “goodness of fit”. One does not have to choose between education for sustainability and early childhood education, underscoring the description of early childhood education as having “all the possibilities in the world” [50] (p. 369) to further human–nature flourishing and a more just, sustainable world.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in the conceptualization of the study. J.E. served as the lead investigator and author and was responsible for developing the methodology. K.M. led the search process, including the identification of records, accessing articles, and initial screening and coding of articles. Both were involved in the review of articles against eligibility criteria, as well as in the quality appraisal, coding, and mapping processes. K.M. led the data curation, organization, and visualizations, including the creation of tables and compilation of references. P.S. and R.S. served as the external reviewers, confirming the coding and mapping, in the context of establishing dependability of the study’s findings. They also contributed to the review of and revisions to the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Nature play outcome categories, descriptions, and sources.

Table A1.

Nature play outcome categories, descriptions, and sources.

| Outcome Category | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Literacy Development: Knowledge | Development of knowledge of human and natural systems, environmental issues, action strategies, and possible solutions. | NAAEE Framework for Assessing Environmental Literacy [38] |

| Environmental Literacy Development: Affective Attitudes & Values | Development of attitudes and values as well as environmental sensitivity, environmental concern, sense of personal responsibility, self-efficacy, motivation, and intentions in an environmental behavior context. | NAAEE Framework for Assessing Environmental Literacy [38] |

| Environmental Literacy Development: Skills and Competencies | Development of skills and abilities relating to environmental behavior contexts, such as the following skills: identify environmental issues, ask relevant questions, analyze environmental issues, investigate environmental issues, evaluate and make personal judgments about environmental issues, use evidence and experience to defend positions and resolve issues, and create and evaluate plans to resolve environmental issues. | NAAEE Framework for Assessing Environmental Literacy [38] |

| Environmental Literacy Development: Actions/Behaviors | Involvement in behaviors, individually or as a member of a group, that work towards solving current problems and preventing new ones or that further the preservation, conservation, or stewardship of the environment. | NAAEE Framework for Assessing Environmental Literacy [38] |

| Approaches to Learning | Development of initiative, curiosity, attentiveness, engagement, persistence, creativity, processing and using information. Showing an active interest in surroundings, people, and objects. Demonstrating an eagerness to learn. Focusing and maintaining attention, making constructive choices, planning to achieve a goal. Demonstrating originality and inventiveness in a variety of ways. Appropriately expressing one’s unique ideas. Gathering, storing, and organizing information that is perceived through the senses in order to use or apply in new situations. Constructing and using knowledge. | Minnesota Early Childhood Indicators of Progress [39] |

| Cognitive: Language and Literacy | Development of language and communication skills, including acquisition of vocabulary and listening, understanding, communicating and speaking, and emergent reading and writing. | Ardoin and Bowers [36] |

| Cognitive: Math | Development of number knowledge, measurement, patterns, geometry and spatial thinking, and data analysis. | Minnesota Early Childhood Indicators of Progress [39] |

| Cognitive: General | Development of thinking skills, executive function skills, and problem solving in non-content-specific contexts, as well as the acquisition of declarative knowledge. | Ardoin and Bowers [36] |

| Cognitive: Scientific Knowledge and Thinking | Development of scientific knowledge or science process skills such as observing and responding to external stimuli, showing interest in exploring, using objects as tools, using simple strategies to carry out ideas, and building on past experiences to further knowledge. Also includes exploring, acting, or experimenting to gain knowledge and formulate questions; making plans and predictions; and verbally expressing their ideas and thoughts pertaining to the world around them. | Minnesota Early Childhood Indicators of Progress [39] |

| Social and Emotional Development | Development of social skills; prosocial behavior; as well as other traits, dispositions, and skills such as self-regulation, empathy, self- and emotional awareness, self-management, social understanding, relationships, and empathy. | Minnesota Early Childhood Indicators of Progress [39]; Ardoin and Bowers [36] |

| Physical Development | Fine and gross motor skills and movement, as well as attitudes, competencies, and habits to support physical health and well-being. | Ardoin and Bowers [36] |

| Mental Well-being | Development of mental well-being, which serves as a foundation that supports all other aspects of human development, including the ability to realize one’s potential, cope with stress and adversity, and contribute to one’s community. | Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University [40] |

Table A2.

Summary of study authors, locations, program description, participant ages, research methodology, and reported outcomes.

Table A2.

Summary of study authors, locations, program description, participant ages, research methodology, and reported outcomes.

| Author (Year) | Country | Ages | Program Description | Research Methodology | Reported Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashman [51] | United States | 4 year olds | nature-based four-year-old kindergarten at city-owned wildlife sanctuary in partnership with school district; half day daily for school year; licensed teacher and naturalist co-teaching | mixed methods (observation, parent survey, parent and child interviews, Phonological Awareness Literacy Screening assessment) | academic learning/early literacy and numeracy, appreciation and respect for the environment; environmental behaviors (teaching peers/parents about caring for environment), working together toward a goal, nature knowledge |

| Bal and Kaya [52] | Turkey | preschool | forest school located in various outdoor natural environments | qualitative (case study, teacher interviews) | self-awareness, decision making, responsibility, problem-solving, creativity, self-expression, self-confidence, pro-social skills and behaviors (empathy, sociability), fine and gross motor skills, respect for nature |

| Barrable and Booth [53] | United Kingdom: England, Scotland, Wales | 1–8 year olds | nature nurseries providing childcare and early learning in a fully outdoor, natural setting | quantitative (Connection to Nature Index for Parents of Preschool Children) | connection to nature |

| Brussoni et al. [54] | Canada | 2–5 year olds | childcare centers with nature-enhanced outdoor play spaces | mixed methods (quality of space instrument, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire teacher version, Preschool Social Behavior Scale Teacher Form, activity/step tracking, play observations, spatial behavior maps, focus groups) | decreases in depressed affect, antisocial behavior, and moderate to vigorous physical activity; increases in play with natural materials, independent play, and prosocial behaviors; improved socialization, problem-solving, focus, self-regulation, creativity and self-confidence, and reduced stress, boredom, and injury |

| Burgess and Ernst [55] | United States | 3–5 year olds | nature preschool with full- and half-day participants attending several days/week to daily participation throughout the academic year; play takes place in a combination of natural/wild settings and nature playscapes | quantitative (Penn Interactive Peer Play Scale and Preschool Learning Behavior Scale) | positive peer play behaviors/interactions, competence motivation, persistence/attention, and positive attitudes toward learning |

| Cameron-Faulkner et al. [56] | United Kingdom: Wales | 3–5 year olds | outdoor nature exploration in a park/arboretum; child–parent self-guided exploration in response to the prompt, “go on a treasure hunt and see what you can find”; one-time experience, 15 min | qualitative (video/audio recording of parent–child speech interactions) | increase in diversity and specificity of parent–child talk about plants and nature |

| Cloward Drown and Christensen [57] | United States | 3–5 year olds | university-operated preschool with daily free play on naturalized playground | qualitative (observations) | dramatic play associated with loose parts |

| Cordiano et al. [58] | United States | 4 year olds | fully outdoor pre-primary class | quantitative (Penn Interactive Peer Play Scale, Preschool and Kindergarten Behavior Scales, Pretend Play Rating, Kindergarten Readiness Measure, Children’s Attitudes Toward School, Children’s Attitudes Toward Nature) | kindergarten readiness with regard to social–emotional and academic skills; pretend play behaviors |

| Dilek and Atasoy [59] | Turkey | 4–5 year olds | forest preschool in local woodland implemented half-days daily over seven weeks | qualitative (interviews with children, observations) | creativity, motivation, knowledge of cause-and-effect relationship, respect for nature, gross motor development, prudence (risk analysis, self-management, self-control problem solving), self-care, cooperation, prosocial skills (taking turns, helping behaviors), communication (use of new words, dialogues, expression of thoughts/feelings) |

| Elliot et al. [60] | Canada | 5–6 year olds | nature kindergarten in a forest setting, outside half days daily | mixed methods (observation, documentation, narrative, modified nature relatedness assessment game) | collaboration, care for self and others, sense of community and responsibility for others, helping/caring behaviors toward others, processing and using information, observations, making connections/integrating information, describing and recording observations, asking questions, affective connection to nature (kinship, sense of intimacy, “home-ness” with place), caring behaviors toward nature, exploratory skills, effort/engagement/persistence in context of tasks |

| Ernst and Burcak [2] | United States | 3–5 year olds | nature preschool with full- and half-day participants attending several days/weeks to daily participation throughout the academic year; play takes place in a combination of natural/wild settings and nature playscapes | quantitative (Curiosity Drawer Box) | curiosity (other outcomes reported in prior publications) |

| Ernst et al. [61] | United States | 3–5 year olds | nature preschool with full- and half-day participants attending several days/weeks to daily participation throughout the academic year; play takes place in a combination of natural/wild settings and nature playscapes | quantitative (Devereux Early Childhood Assessment for Preschoolers) | resilience (protective factors) |

| Fyfe-Johnson et al. [62] | United States | 3–5 year olds | nature preschool in forested park, half-day programming entirely outdoors in a forested park | quantitative (accelerometers for PA tracking; Strengths and Difficulties parent questionnaire) | high levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity; positive parental attitudes toward outdoor play in cold weather nature preschools were more tolerant of colder conditions for outdoor play |

| Green [63] | United States | 5–8 year olds | kindergarten through 3rd grade classes participating in two days of field excursions, exploring sub alpine forest hills with an adult and peer | qualitative (“Sensory Tours”: analysis of videos generated from children’s wearable cameras) | sense of trust/comfort in nature, knowledge of local plans/animals, spatial autonomy/sense of independence and self-confidence in nature, exploration/experimentation/model building, care for living creatures, environmental identity (feeling part of natural world) |

| Green and Lliaban [64] | United States | 5–6 year olds | kindergarten class in a rural, Indigenous Alaskan village | qualitative (content analysis of children’s drawings/descriptions) | awareness/sensitivities to natural surroundings; knowledge of local plants and animals, spatial autonomy toward agency with place, environmental identity, healthy dispositions towards other living beings, sense of belonging in their place |

| Haas and Ashman [32] | Australia | K age | kindergarten program (15 h/week) with nature play in school yard and weekly walking excursions to forest reserve for play and exploration | qualitative (observations, interviews) | more expansive forms of play, decreased negative play behaviors (tattling, unfair play, leaving children out), positive relationships with peers and adults, perseverance, persistence to overcome difficulties, attention restoration, physical capabilities (balance, movement), positive social interactions, complex ideas, biophilia, environmental dispositions and values |

| Heldal et al. [65] | Greece | 2–6 year olds | fully outdoor early childhood education care center in a refugee camp with a wooded area, serving children from within and external to the refugee camp | qualitative (participant observations, individual and group interviews) | respectful, caring behaviors toward wildlife, communication skills, restorative/calming effects, exploratory skills, self-challenge/management, valuing of life within nature, citizenship/civic skills, sense of belonging, self-awareness, respect toward peers/adults, feelings of at home in the world, feelings of inclusion and equality across genders and cultures |

| Kahriman-Pamuk [66] | Turkey | 3–5 year olds | forest school where children spent all day outdoors in the forest located near an urban area | qualitative (parent interviews) | environmental awareness and knowledge, compassionate care for nature, self-confidence, taking responsibility, physical strength and speed, inquiry skills |

| Kochanowski and Carr [67] | United States | 3–5 year olds | three one-hour off-site play sessions in a natural playscape | qualitative (observations) | choice-making, problem-solving, engagement, self-regulation, determination, intrinsic motivation |

| Lai et al. [68] | Hong Kong | 4–6 year olds | one hour of unstructured play outdoors with loose parts, followed by 10 min of mindfulness; conducted for 5 consecutive days in context of kindergarten | quantitative (parent questionnaire, pedometer for activity tracking, Smiley Face Likert Scale, Children’s Emotional Manifestation Scale, Penn Interactive Peer Play Scale, Test of Playfulness Scale) | mental well-being (happiness) and playfulness/disposition to engage in play |

| MacDonald and Breunig [69] | Canada | 4–5 year olds | outdoor classroom in context of full day kindergarten program | qualitative (child and teacher interviews) | social development, health and physical activity, scientific thinking, literacy and communication skills, patterns, gross motor skills, observation skills, respectful interactions with nature, connection to nature |

| McClain and Vandermaas-Peeler [70] | United States | 2–5 year olds | Reggio Emilia preschool with half-day programming four days per week with weekly visits to a state park | qualitative (observation, child and teacher interviews) | awareness of and connection to environmental surroundings, skills for being in/moving about in/interacting with the natural environment, knowledge of local plants and animals, observation skills, classification skills, early scientific reasoning, communication skills, exploration, using evidence to answer questions, making and testing hypotheses, stewardship; combining scientific principles or discoveries with valuing nature |

| McCree et al. [71] | United Kingdom: England | 5–7 year olds | weekly forest school offered year-round over three years, facilitated by leaders and parents | mixed methods (Connection to Nature Index, Leuven Scale measures, parent and child and staff questionnaires, interviews, case studies, mosaic approach, draw and write method) | mental well-being, self-confidence, self-esteem, engagement, connection to nature, academic skill attainment in reading, writing, math, attachment, self-regulation, resilience, spatial autonomy/self-confidence/trust in nature, independence, sharing environmental knowledge with others |

| McVittie [72] | Canada | 2–5 year olds | daycare with visits once per week for several months to naturalized areas | qualitative (observations) | sensory observation of the world, language development and word acquisition, adjusting physical movement with varied terrain, languaged and non-languaged exploratory behavior |

| Meyer, et al. [73] | Canada | K age | nature-based kindergartens that spend half the day outdoors with visits to beach, city park, unmaintained natural area, natural and artificial playgrounds | quantitative (OSRAC-P Sampling Observation System coding for gross body movements and activity types) | increased physical activity and greater breadth of activity types, moderate and vigorous gross body movements and a greater breadth of specific activity types |

| Nedovic and Morrissey [74] | Australia | 3–4 year olds | childcare center with a garden and child–teacher co-designed naturalized play space | qualitative (mosaic approach, interviews, conversations, photos, and drawings) | physical activity, confidence in physical skills, mental well-being (calmer, relaxed, less stressed and agitated), depth of imagination, frequency and depth of dramatic play, observation skills, focused/attentive |

| Omidvar et al. [75] | Canada | 3–5 year olds | full-day Reggio Emilia preschools with 3 h/day outdoors in nature | quantitative (Games Testing for Emotional, Cognitive, and Attitudinal Affinity with the Biosphere) | participation did not result in strong bio-affinity; may have been due to influence of children’s socio-cultural background, the pedagogical approach itself, or its implementation at these schools, but may also have been due to the research instrument’s ability to test for bio-affinity amongst this age group in Canada and the need for further testing of instrument appropriateness for various settings, ages, and cultures |

| Schlembach et al. [76] | United States | 3–5 year olds | preschool (Head Start) affiliated with university, with weekly visits to a nature playscape in an urban area | mixed methods (survey and in-person interviews, observations, field notes, and video and photo documentation) | freedom and autonomy toward self-confidence, competence, and independence; sense of belonging, problem-solving and inquiry skills, goal-oriented collaborative play to complete a task, negotiation and collaboration, less play disruption/challenging behaviors, holistic development |

| Volpe et al. [77] | United States | K–5th grade | afterschool outdoor nature school, where 1st–5th grade students spend 2–4 h daily outdoors in nature afterschool in coastal scrub, oak woodlands, dunes, redwood forest | mixed methods (parent questionnaires, observations, and child interviews) | new perspectives, confidence, social and emotional development, holistic development |

| Wojciehowski and Ernst [78] | United States | 3–6 year olds | nature preschool with full- and half-day participants attending several days/week to daily participation throughout the academic year; play takes place in a combination of natural/wild settings and nature playscapes | quantitative (Thinking Creatively in Action and Movement Tool) | creative thinking |

| Yılmaz et al. [79] | Turkey | 4 year olds | weekly day-long visits to a natural, wooded area on university campus for 4 weeks | quantitative (Children’s Biophilia Measure) | affinity toward nature |

| Zamzow and Ernst [80] | United States | 4 year olds | nature preschool with full- and half-day participants attending several days/weeks to daily participation throughout the academic year; play takes place in a combination of natural/wild settings and nature playscapes | quantitative (Minnesota Executive Function Scale) | executive function skills |

Table A3.

Results of the coding of study outcomes into the outcome categories.

Table A3.

Results of the coding of study outcomes into the outcome categories.

| Category | Outcome | Study |

| Environmental Literacy Development: Knowledge | Knowledge about nature | [51] |

| Knowledge of local plants and animals | [63,64,70] | |

| Knowledge of cause-and-effect relationships | [59] | |

| Knowledge of growing/harvesting local food | [63] | |

| Environmental awareness and knowledge | [66] | |

| Use of plant/nature terminology | [56] | |

| Environmental Literacy Development: Affective Attitudes and Values | Affinity toward nature/biophilia | [32,79] |

| Connection to nature | [53,60,69,70,71] | |

| Connection to other living things | [64] | |

| Sense of intimacy and at home-ness in nature | [60,65] | |

| Sense of belonging in/attachment to place | [64] | |

| Environmental identity | [63,64] | |

| Awareness of and sensitivities to natural/environmental surroundings | [64,70] | |

| Appreciation and respect for nature | [51,52,59] | |

| Environmental dispositions and values; valuing of life within nature | [32,65] | |

| Environmental Literacy Development: Skills and Competencies | Skills for being in/moving about in/interacting with natural environment | [70] |

| Spatial autonomy (sense of comfort, independence, and self-confidence) in nature | [64,71,76] | |

| Trust in interactions in/with nature | [63,71] | |

| Environmental Literacy Development: Actions/Behaviors | Respectful interactions with nature | [69] |

| Stewardship of/caring for plants, wildlife, living creatures, and/or nature; compassionate care for nature | [59,60,63,65,66,70] | |

| Sharing environmental knowledge with others | [71] | |

| Modeling/monitoring for pro-environmental behavior with peers and family (such as making sure family recycles, teaching other children about how to treat animals) | [51] | |

| Citizenship, civic skills | [65] | |

| Approaches to Learning | Creativity, creative thinking, imagination | [54,59,74,78] |

| Curiosity | [2] | |

| Languaged and non-languaged exploratory behavior | [70,72] | |

| Exploratory skills | [60,63,65,72] | |

| Focus, attention | [54,55,74] | |

| Persistence, perseverance, determination | [32,55,60,67] | |

| Processing and using information | [59,60] | |

| Engagement | [67,68,71] | |

| Motivation | [55,59,67] | |

| Feelings of competence | [55,76] | |

| Positive attitudes toward learning | [55] | |

| Risk analysis | [59] | |

| Cognitive: General | Decision making | [52] |

| Choice making | [67] | |

| Complex ideas thinking | [32] | |

| Executive function skills | [80] | |

| Cognitive: Language and Literacy | Early literacy skills | [51,58,69,71] |

| Increase in diversity and specificity of parent–child talk about plants and nature; use of plant-related terminology | [56] | |

| Language development, vocabulary development, word acquisition | [59,72] | |

| Verbal expression of thoughts, ideas, and feelings | [59,60] | |

| Communication skills | [59,65,69] | |

| Writing skills | [71] | |

| Cognitive: Math | Early numeracy skills | [51,58] |

| Recognizing patterns | [69] | |

| Math skills | [71] | |

| Cognitive: Scientific Knowledge and Thinking | Asking questions | [60] |

| Making, describing, and recording observations | [60,69,70,74] | |

| Sensory observation of the world | [72] | |

| Classification skills | [70] | |

| Using evidence to answer questions | [70] | |

| Inquiry skills | [66,76] | |

| Scientific thinking and reasoning | [59,69,70] | |

| Making connections and integrating information | [60] | |

| Problem solving | [54,59,76] | |

| Model building | [63] | |

| Making and testing | [63,70] | |

| Communicating about science | [70] | |

| Social and Emotional Development | Social–emotional skills, social development | [58,69,77] |

| Prosocial behavior; decreased antisocial or challenging behaviors | [32,52,54,76] | |

| Goal-directed cooperation or collaboration | [51,60,76] | |

| Helping behavior-directed cooperation or collaboration | [54] | |

| Negotiation | [76] | |

| Positive peer play interactions; decreased play disruptions; decreased play disconnections | [32,55,58] | |

| Sense of community/belonging; feelings of “at home” in the world; feelings of inclusion and equality across genders and cultures | [60,65,76] | |

| Empathy; sense of compassion, concern, or responsibility for others | [52,59,60] | |

| New perspectives | [77] | |

| Respect for/positive relationships with adults and peers | [32,65] | |

| Responsibility for actions | [52,66] | |

| Self-confidence | [52,54,66,71,76,77] | |

| Self-expression | [52] | |

| Self-awareness | [52,65] | |

| Self-regulation; self-management; self-control | [54,59,60,65,67,71] | |

| Self-care | [59,60] | |

| Independence | [76] | |

| Resilience; protective factors associated with resilience | [60,71] | |

| Physical Development | Fine motor skills | [52] |

| Gross motor skill development | [52,59,69] | |

| Physical capabilities (movement, balance, strength, speed, adjustment of movement in response to terrain, stamina) | [32,51,66,72] | |

| Confidence in physical skills | [74] | |

| Increased physical activity | [62,69,73,74] | |

| Greater breadth of activity types | [73] | |

| Physical health stamina | [51,69] | |

| Reduced injury | [54] | |

| Positive parent attitudes toward outdoor play in cold weather | [62] | |

| Mental Well-being Development | Decreased depressed affect | [54] |

| Reduced boredom | [54] | |

| Attention restoration, restorative effects | [32,65] | |

| Stress reduction (calmer, less agitated) | [54,65,71,74] | |

| Feelings of happiness | [68] | |

| Other: Changes in Play Behavior | Increased play with natural materials; increased independent play | [54] |

| Higher levels of pretend play | [58] | |

| More expansive forms of play | [32] | |

| Frequency and depth of dramatic play | [57,74] | |

| Other | Combining scientific principles or discoveries with valuing nature (integrating domains) | [70] |

| Holistic development | [76,77] |

Table A4.

Alignment of nature play outcomes with the ECEfS outcomes [41,42].

Table A4.

Alignment of nature play outcomes with the ECEfS outcomes [41,42].

| Standards and Indicators | Outcomes Associated with Nature Play | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Category | Specific Outcome | Source | ||

| Benchmark: Applied Knowledge | ||||

Cultural Preservation and Transformation

| Environmental Literacy Development: Knowledge | Knowledge of growing/harvesting local food | [63] | |

Responsible Local and Global Citizenship

| Cognitive: General | Decision making | [52] | |

| Choice making | [67] | |||

| Executive function skills | [80] | |||

| Cognitive: Scientific Knowledge and Thinking | Problem solving | [54,59,76] | ||

| Social and Emotional Development | Helping behavior-directed cooperation or collaboration | [59] | ||

| Social–emotional skills, social development | [58,69,77] | |||

| Prosocial behavior; decreased antisocial or challenging behaviors | [32,52,54,60,76] | |||