Cross-Cultural Perspectives on the Role of Empathy during COVID-19’s First Wave

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

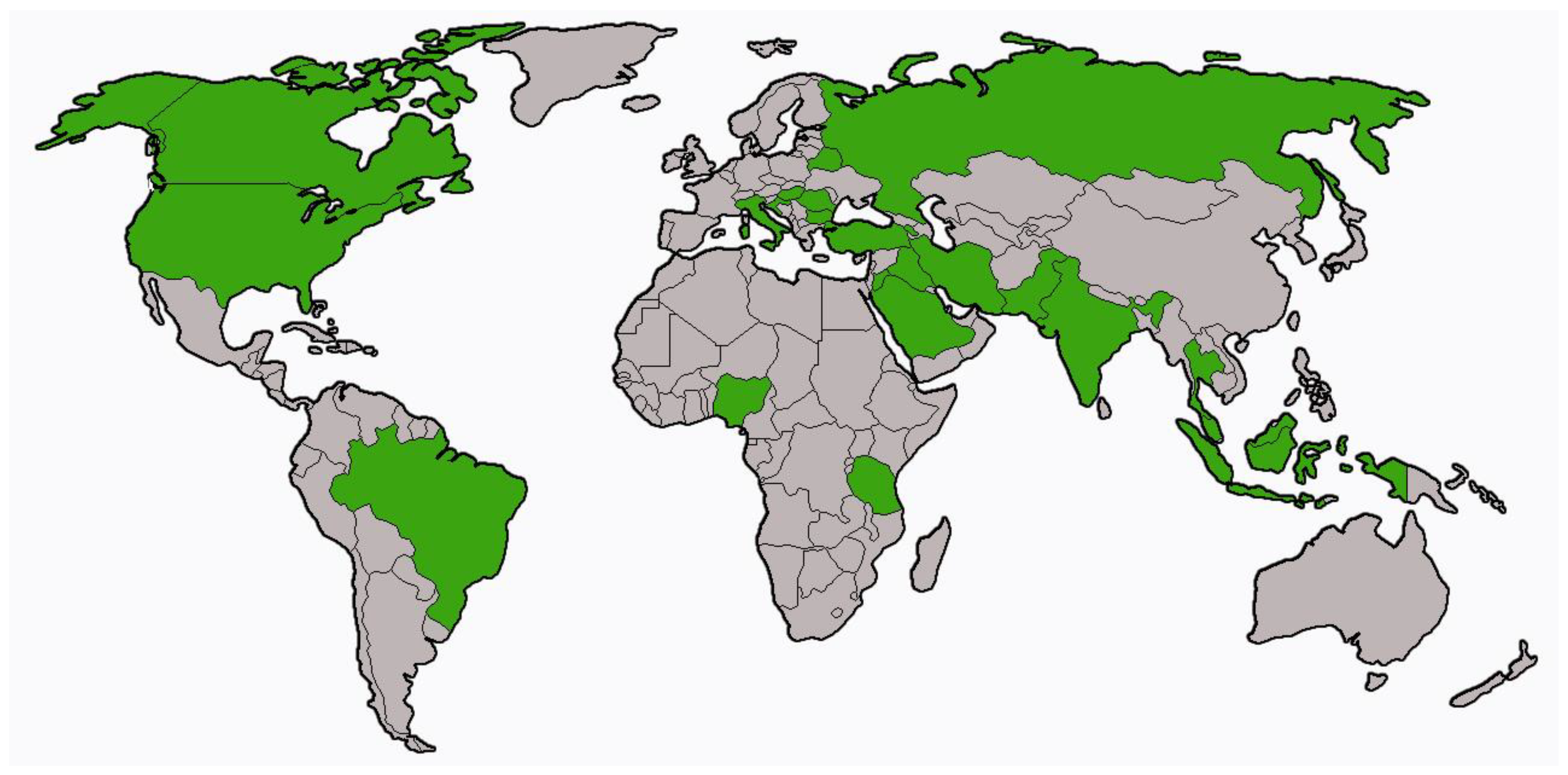

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

Empathy

2.4. Global Indices Used in This Study

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethics Statement

3. Results

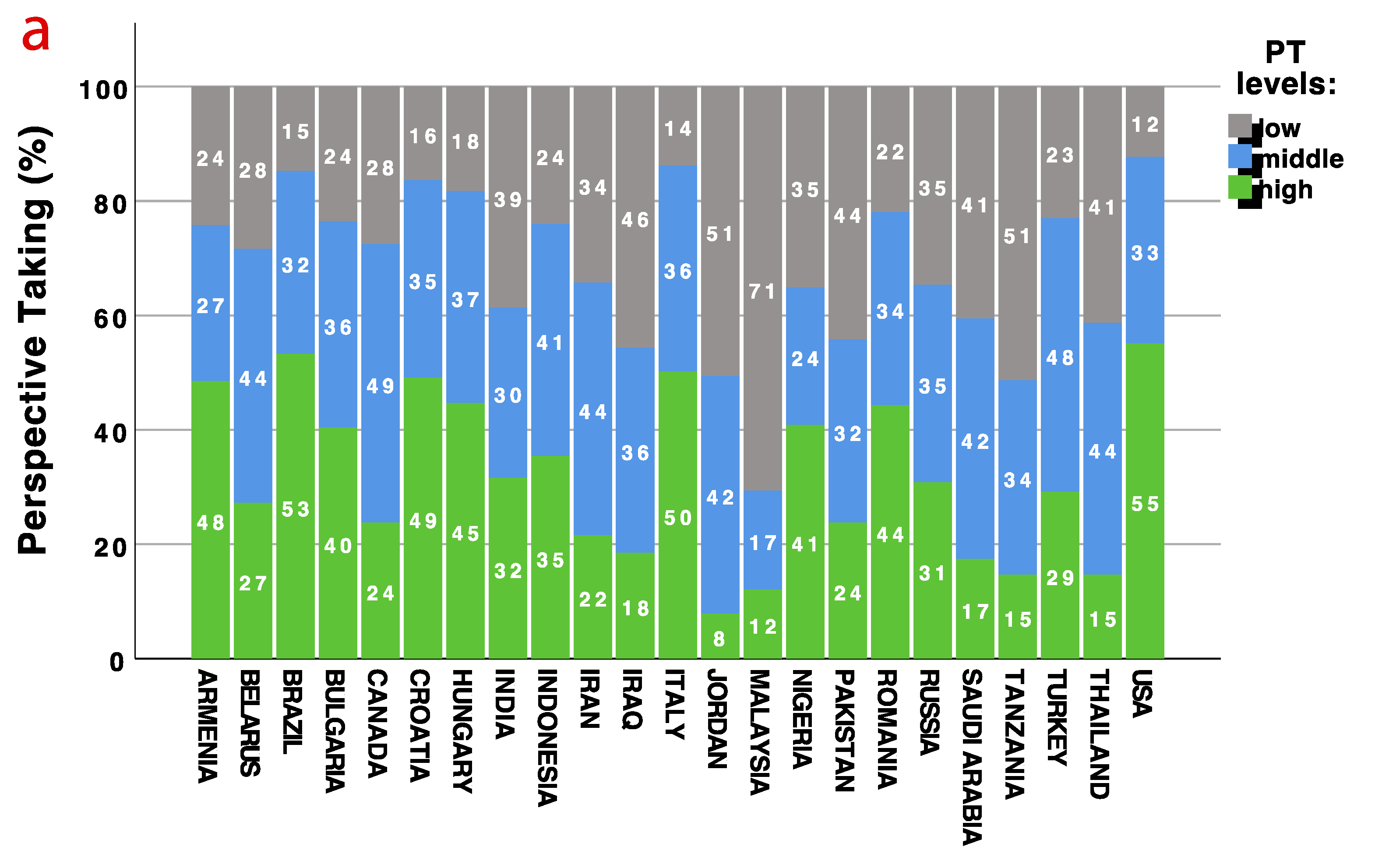

3.1. Variations on IRI Scores across Total Sample and within Countries

| Perspective-Taking | Empathic Concern | Personal Distress | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 15,294 | 15,294 | 15,289 |

| Mean | 16.87 | 17.26 | 13.69 |

| Std. Deviation | 4.75 | 5.27 | 4.83 |

| Minimum | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Maximum | 28.00 | 28.00 | 28.00 |

3.2. Sex and Country Differences on Empathy Scores

| Country | IRI Subscales. | N | Sex | Mean | SD | t | df | p | 95% CI | Hedges’ g * | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||||

| ARMENIA | Perspective-Taking | 27 6 | men women | 19.26 13.50 | 4.97 5.05 | 2.563 | 31 | 0.015 | 1.176 | 10.343 | 1.128 | 0.577 |

| Empathic Concern | 27 6 | men women | 17.74 15.33 | 4.40 2.80 | 1.275 | 31 | 0.212 | −1.443 | 6.258 | 0.561 | 0.307 | |

| Personal Distress | 27 6 | men women | 13.07 12.33 | 6.36 3.50 | 0.274 | 31 | 0.786 | −4.775 | 6.257 | 0.121 | 0.705 | |

| BELARUS | Perspective-Taking | 143 195 | men women | 16.45 17.36 | 4.92 4.44 | −1.790 | 336 | 0.074 | −1.924 | 0.090 | −0.197 | 0.661 |

| Empathic Concern | 143 195 | men women | 15.74 18.02 | 4.46 4.54 | −4.585 | 336 | <0.001 | −3.250 | −1.299 | −0.504 | 0.622 | |

| Personal Distress | 143 195 | men women | 10.37 14.01 | 4.73 4.62 | −7.081 | 336 | <0.001 | −4.651 | −2.629 | −0.778 | 0.712 | |

| BRAZIL | Perspective-Taking | 82 430 | men women | 19.40 19.41 | 4.66 4.71 | −0.020 | 510 | 0.984 | −1.125 | 1.102 | −0.002 | 0.669 |

| Empathic Concern | 82 430 | men women | 20.63 22.30 | 4.44 4.36 | −3.167 | 510 | 0.002 | −2.703 | −0.633 | −0.381 | 0.607 | |

| Personal Distress | 82 430 | men women | 12.76 15.92 | 5.63 5.62 | −4.668 | 510 | <0.001 | −4.497 | −1.833 | −0.562 | 0.743 | |

| BULGARIA | Perspective-Taking | 129 193 | men women | 16.91 18.63 | 4.80 4.16 | −3.317 | 247 | <0.001 | −2.737 | −0.698 | −0.387 | 0.688 |

| Empathic Concern | 129 193 | men women | 17.27 19.54 | 3.78 4.02 | −5.079 | 320 | <0.001 | −3.146 | −1.389 | −0.576 | 0.621 | |

| Personal Distress | 129 193 | men women | 12.78 14.86 | 4.50 5.05 | −3.791 | 320 | <0.001 | −3.167 | −1.003 | −0.430 | 0.753 | |

| CANADA | Perspective-Taking | 383 227 | men women | 16.27 17.82 | 3.85 4.31 | −4.491 | 433 | <0.001 | −2.239 | −0.876 | −0.387 | 0.629 |

| Empathic Concern | 383 227 | men women | 15.95 17.67 | 3.93 5.21 | −4.298 | 379 | <0.001 | −2.507 | −0.933 | −0.386 | 0.686 | |

| Personal Distress | 383 227 | men women | 13.28 14.41 | 4.11 4.46 | −3.183 | 605 | 0.002 | −1.831 | −0.434 | −0.267 | 0.639 | |

| CROATIA | Perspective-Taking | 71 204 | men women | 18.59 19.33 | 4.73 4.27 | −1.227 | 273 | 0.221 | −1.932 | 0.449 | −0.169 | 0.737 |

| Empathic Concern | 71 204 | men women | 16.82 20.77 | 4.28 4.36 | −6.622 | 273 | <0.001 | −5.134 | −2.781 | −0.910 | 0.758 | |

| Personal Distress | 71 204 | men women | 11.21 13.97 | 4.11 3.75 | −5.197 | 273 | <0.001 | −3.798 | −1.711 | −0.714 | 0.624 | |

| HUNGARY | Perspective-Taking | 35 198 | men women | 15.86 18.98 | 5.30 4.59 | −3.625 | 231 | <0.001 | −4.828 | −1.428 | −0.662 | 0.696 |

| Empathic Concern | 35 198 | men women | 17.09 21.35 | 4.25 4.61 | −5.097 | 231 | <0.001 | −5.911 | −2.615 | −0.932 | 0.714 | |

| Personal Distress | 35 198 | men women | 9.49 11.63 | 5.41 5.52 | −2.126 | 231 | <0.001 | −4.134 | −0.157 | −0.389 | 0.771 | |

| INDIA | Perspective-Taking | 213 170 | men women | 16.42 16.70 | 4.95 5.29 | −0.537 | 381 | <0.001 | −1.315 | 0.750 | −0.055 | 0.653 |

| Empathic Concern | 213 170 | men women | 17.66 18.36 | 4.64 5.55 | −1.323 | 329 | 0.187 | −1.748 | 0.342 | −0.139 | 0.679 | |

| Personal Distress | 213 170 | men women | 11.95 13.72 | 4.73 4.53 | −3.705 | 381 | <0.001 | −2.708 | −0.830 | −0.380 | 0.574 | |

| INDONESIA | Perspective-Taking | 504 424 | men women | 16.71 18.77 | 4.49 3.85 | −7.540 | 926 | <0.001 | −2.602 | −1.527 | −0.490 | 0.540 |

| Empathic Concern | 504 424 | men women | 18.96 20.99 | 4.65 4.40 | −6.782 | 926 | <0.001 | −2.615 | −1.441 | −0.447 | 0.596 | |

| Personal Distress | 504 424 | men women | 12.76 16.24 | 4.09 4.62 | −12.026 | 852 | <0.001 | −4.044 | −2.909 | −0.800 | 0.569 | |

| IRAN | Perspective-Taking | 88 217 | men women | 15.81 16.43 | 4.32 4.74 | −1.073 | 303 | 0.284 | −1.775 | 0.523 | −0.135 | 0.635 |

| Empathic Concern | 88 217 | men women | 16.84 18.32 | 4.81 4.10 | −2.539 | 141 | 0.012 | −2.635 | −0.328 | −0.342 | 0.532 | |

| Personal Distress | 88 217 | men women | 13.01 13.47 | 3.69 4.24 | −0.879 | 303 | 0.380 | −1.471 | 0.563 | −0.111 | 0.444 | |

| IRAQ | Perspective-Taking | 88 85 | men women | 14.94 15.11 | 4.74 4.72 | −0.226 | 171 | 0.821 | −1.582 | 1.256 | −0.034 | 0.497 |

| Empathic Concern | 88 85 | men women | 16.15 17.12 | 4.04 4.52 | −1.489 | 171 | 0.138 | −2.256 | 0.316 | −0.225 | 0.331 | |

| Personal Distress | 88 85 | men women | 12.02 13.18 | 3.92 4.19 | −1.870 | 171 | 0.063 | −2.372 | 0.064 | −0.283 | 0.360 | |

| ITALY | Perspective-Taking | 44 208 | men women | 18.16 19.50 | 4.50 4.22 | −1.898 | 250 | 0.059 | −2.742 | 0.051 | −0.314 | 0.676 |

| Empathic Concern | 44 208 | men women | 19.57 21.14 | 4.96 3.95 | −2.288 | 250 | 0.023 | −2.924 | −0.219 | −0.379 | 0.560 | |

| Personal Distress | 44 208 | men women | 12.73 14.15 | 5.53 4.84 | −1.726 | 250 | 0.086 | −3.044 | 0.201 | −0.286 | 0.722 | |

| JORDAN | Perspective-Taking | 121 328 | men women | 14.36 14.55 | 3.45 3.57 | −0.508 | 447 | 0.612 | −.932 | 0.549 | −0.054 | 0.489 |

| Empathic Concern | 121 328 | men women | 15.41 15.72 | 4.22 3.95 | −0.708 | 447 | 0.479 | −1.145 | 0.539 | −0.075 | 0.519 | |

| Personal Distress | 121 328 | men women | 13.09 13.69 | 2.85 3.18 | −1.806 | 447 | 0.072 | −1.243 | 0.053 | −0.192 | 0.456 | |

| MALAYSIA | Perspective-Taking | 478 609 | men women | 12.31 13.09 | 4.37 4.60 | −2.823 | 1046 | 0.005 | −1.308 | −0.235 | −0.171 | 0.441 |

| Empathic Concern | 478 609 | men women | 10.92 12.13 | 4.54 4.36 | −4.477 | 1085 | <0.001 | −1.746 | −0.682 | −0.273 | 0.469 | |

| Personal Distress | 478 609 | men women | 11.88 12.86 | 3.65 4.11 | −4.113 | 1069 | <0.001 | −1.434 | −0.508 | −0.248 | 0.390 | |

| NIGERIA | Perspective-Taking | 214 102 | men women | 17.38 17.38 | 5.97 5.70 | 0.001 | 207 | 0.999 | −1.372 | 1.374 | 0.000 | 0.674 |

| Empathic Concern | 214 102 | men women | 18.93 19.93 | 5.62 5.51 | −1.490 | 314 | 0.137 | −2.324 | 0.321 | −0.179 | 0.663 | |

| Personal Distress | 214 102 | men women | 11.80 13.54 | 4.33 4.74 | −3.236 | 314 | 0.001 | −2.798 | −0.682 | −0.388 | 0.468 | |

| PAKISTAN | Perspective-Taking | 212 272 | men women | 14.42 16.00 | 5.04 5.09 | −3.402 | 482 | 0.001 | −2.491 | −0.667 | −0.311 | 0.557 |

| Empathic Concern | 212 272 | men women | 15.58 17.59 | 4.38 5.13 | −4.659 | 478 | <0.001 | −2.867 | −1.166 | −0.418 | 0.510 | |

| Personal Distress | 212 272 | men women | 12.31 13.83 | 4.27 4.51 | −3.763 | 482 | <0.001 | −2.313 | −0.726 | −0.344 | 0.406 | |

| ROMANIA | Perspective-Taking | 42 226 | men women | 17.05 18.85 | 6.01 4.78 | −1.843 | 51 | 0.071 | −3.774 | 0.161 | −0.361 | 0.764 |

| Empathic Concern | 42 226 | men women | 17.57 19.58 | 4.48 4.29 | −2.766 | 266 | 0.006 | −3.438 | −0.579 | −0.463 | 0.622 | |

| Personal Distress | 42 226 | men women | 8.93 10.87 | 5.50 5.12 | −2.231 | 266 | 0.027 | −3.658 | −0.229 | −0.374 | 0.751 | |

| RUSSIA | Perspective-Taking | 486 1417 | men women | 16.22 16.84 | 5.27 5.09 | −2.286 | 1901 | 0.022 | −1.147 | −0.088 | −0.120 | 0.651 |

| Empathic Concern | 486 1417 | men women | 16.06 17.44 | 4.36 4.52 | −5.874 | 1901 | <0.001 | −1.845 | −0.921 | −0.309 | 0.524 | |

| Personal Distress | 486 1417 | men women | 10.43 13.28 | 4.97 4.81 | −11.162 | 1901 | <0.001 | −3.349 | −2.348 | −0.587 | 0.636 | |

| SAUDI ARABIA | Perspective-Taking | 98 316 | men women | 15.18 15.79 | 3.63 3.97 | −1.342 | 412 | 0.180 | −1.489 | 0.281 | −0.155 | 0.554 |

| Empathic Concern | 98 316 | men women | 16.45 17.64 | 4.16 4.65 | −2.403 | 178 | 0.017 | −2.168 | −0.213 | −0.262 | 0.636 | |

| Personal Distress | 98 316 | men women | 13.97 14.81 | 3.51 3.45 | −2.101 | 412 | 0.036 | −1.627 | −0.054 | −0.243 | 0.418 | |

| TANZANIA | Perspective-Taking | 185 156 | men women | 13.96 15.40 | 4.47 4.72 | −2.880 | 339 | 0.004 | −2.416 | −0.455 | −0.312 | 0.358 |

| Empathic Concern | 185 156 | men women | 14.01 15.31 | 3.91 4.75 | −2.731 | 300 | 0.007 | −2.241 | −0.364 | −0.301 | 0.435 | |

| Personal Distress | 185 156 | men women | 12.62 14.27 | 3.91 4.20 | −3.759 | 339 | <0.001 | −2.518 | −0.788 | −0.408 | 0.353 | |

| TURKEY | Perspective-Taking | 1609 3093 | men women | 16.79 17.65 | 4.06 3.96 | −7.040 | 4700 | <0.001 | −1.105 | −0.623 | −0.216 | 0.546 |

| Empathic Concern | 1609 3093 | men women | 15.10 17.24 | 4.52 5.18 | −14.622 | 3669 | <0.001 | −2.423 | −1.850 | −0.430 | 0.627 | |

| Personal Distress | 1609 3093 | men women | 14.14 15.85 | 4.59 4.44 | −12.231 | 3162 | <0.001 | −1.981 | −1.433 | −0.380 | 0.557 | |

| THAILAND | Perspective-Taking | 49 250 | men women | 15.45 16.03 | 2.34 3.54 | −1.441 | 97 | 0.153 | −1.377 | 0.219 | −0.171 | 0.524 |

| Empathic Concern | 49 250 | men women | 16.45 17.20 | 2.72 3.55 | −1.400 | 297 | 0.162 | −1.807 | 0.304 | −0.218 | 0.506 | |

| Personal Distress | 49 250 | men women | 12.71 13.27 | 2.75 3.14 | −1.159 | 297 | 0.247 | −1.505 | 0.389 | −0.181 | 0.485 | |

| USA | Perspective-Taking | 181 460 | men women | 19.28 20.04 | 4.94 4.52 | −1.859 | 639 | 0.063 | −1.557 | 0.043 | −0.163 | 0.780 |

| Empathic Concern | 181 460 | men women | 20.70 22.68 | 5.15 4.32 | −4.576 | 285 | <0.001 | −2.833 | −1.129 | −0.433 | 0.795 | |

| Personal Distress | 181 460 | men women | 9.85 10.25 | 5.50 5.87 | −0.801 | 637 | 0.423 | −1.400 | 0.589 | −0.070 | 0.830 | |

| TOTAL | Perspective-Taking | 5482 9786 | men women | 16.14 17.28 | 4.78 4.69 | −14.131 | 11168 | <0.001 | −1.289 | −0.975 | −0.240 | 0.603 |

| Empathic Concern | 5482 9786 | men women | 15.99 17.97 | 5.02 5.27 | −22.898 | 11824 | <0.001 | −2.143 | −1.804 | −0.381 | 0.661 | |

| Personal Distress | 5479 9784 | men women | 12.62 14.29 | 4.63 4.85 | −21.020 | 11788 | <0.001 | −1.825 | −1.514 | −0.350 | 0.584 | |

3.2.1. Empathy Ratings Depending on Culture, Religion, Living Conditions, Involvement in Voluntary Activity, and Fear of COVID-19

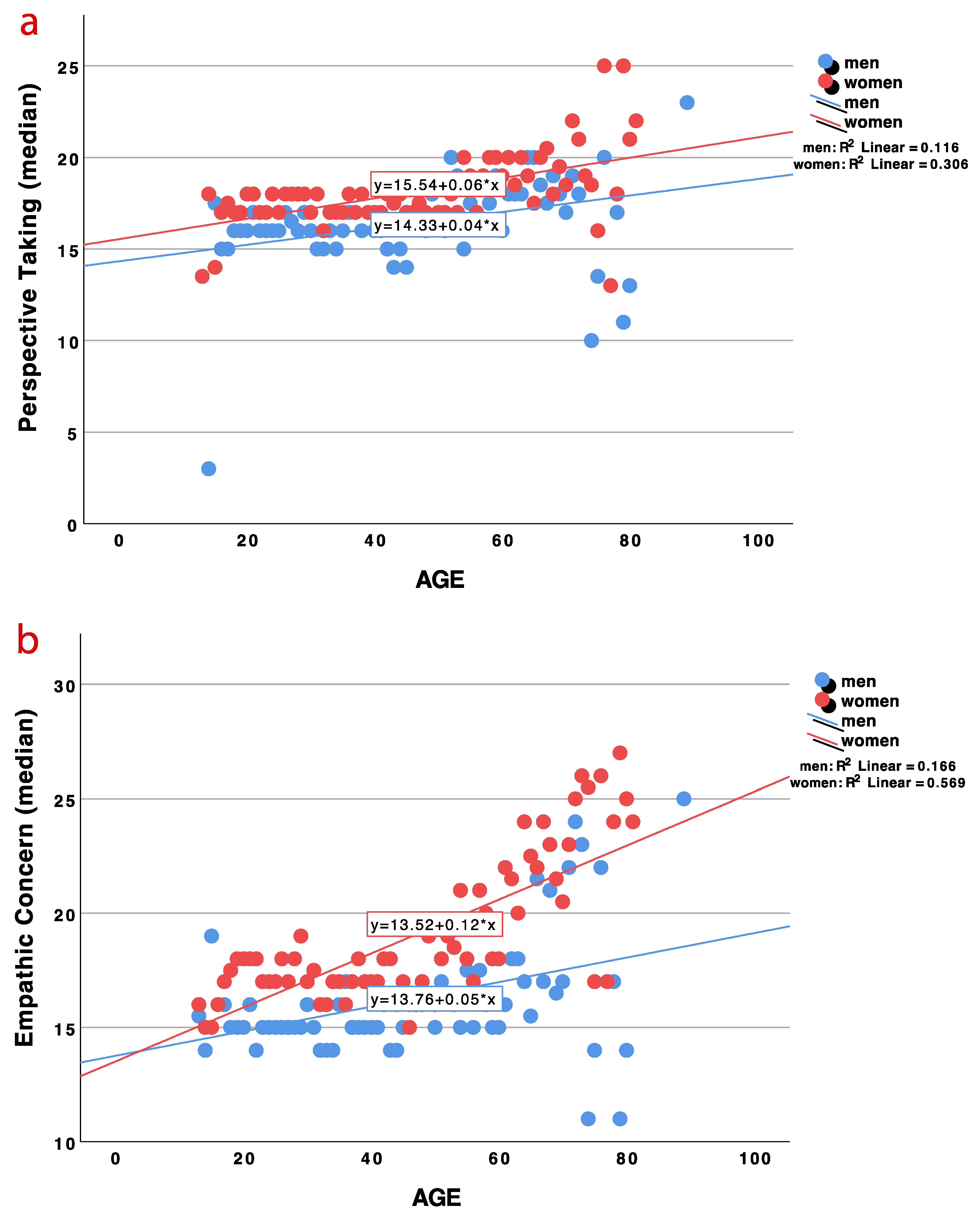

3.2.2. Association between Age, Sex, and Empathy

3.2.3. Association between Global Indices and Empathy

3.2.4. Association between Individualism/Collectivism and Empathy

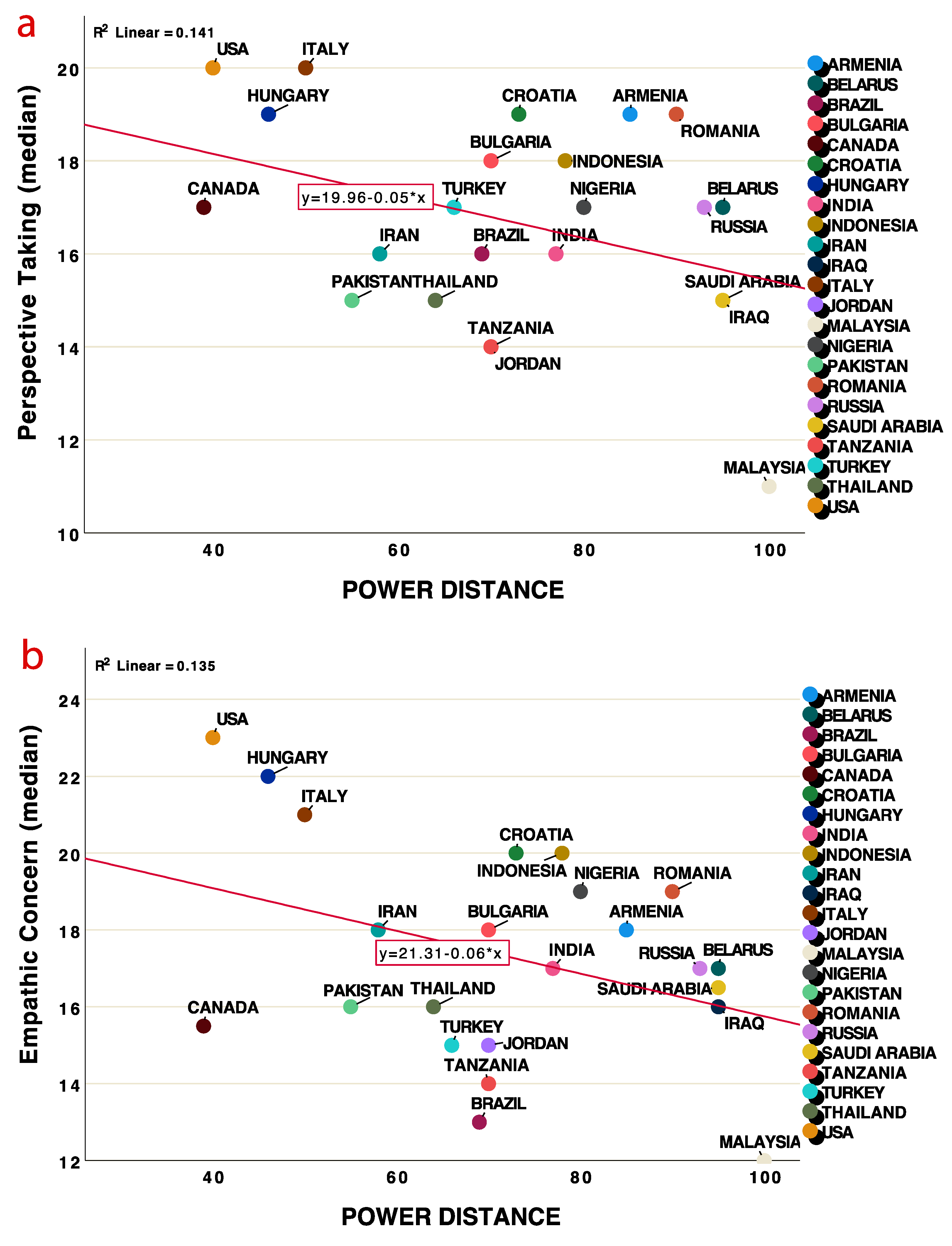

3.2.5. Association between Power Distance and Empathy

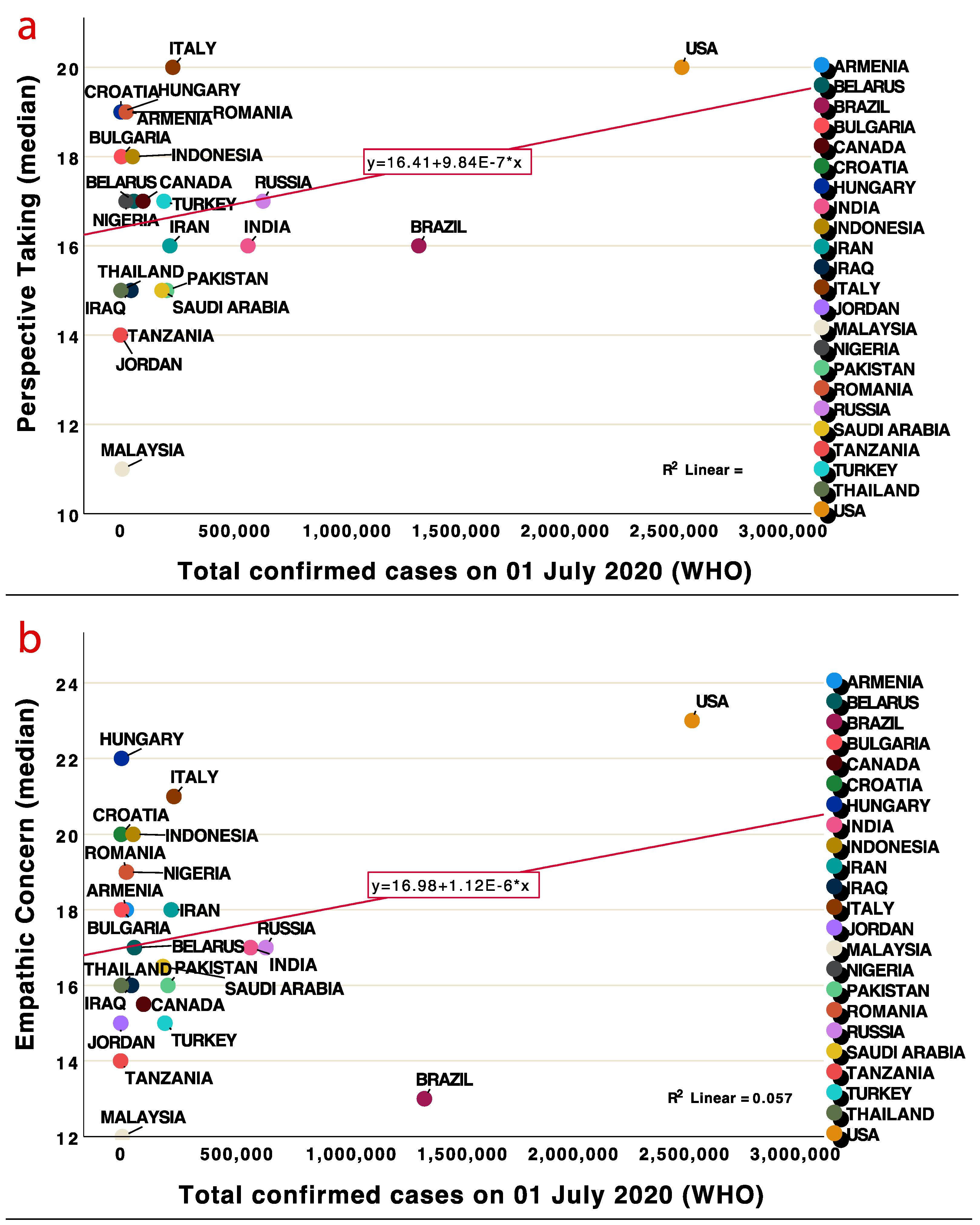

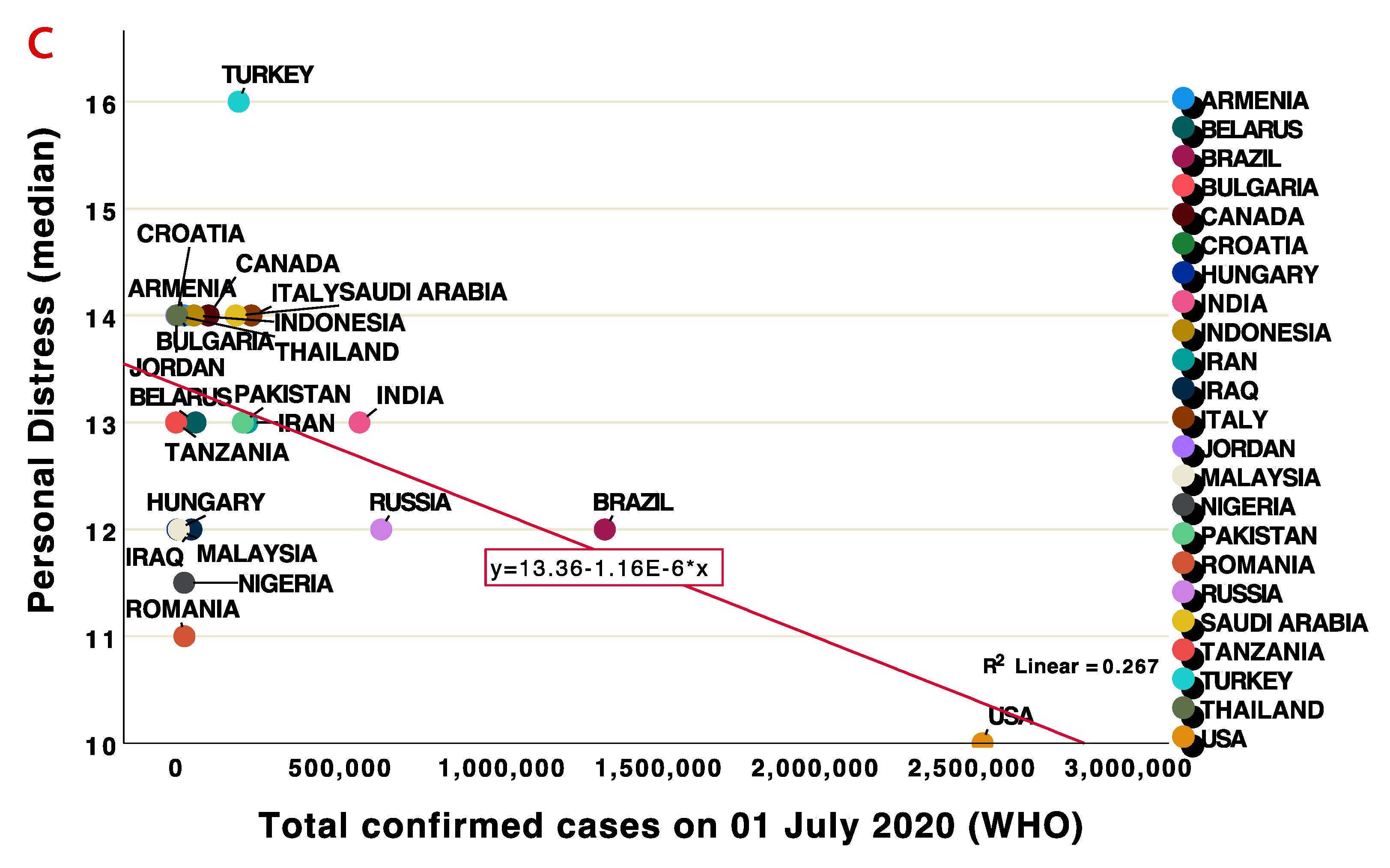

3.2.6. Association between COVID-19 Cases and Empathy

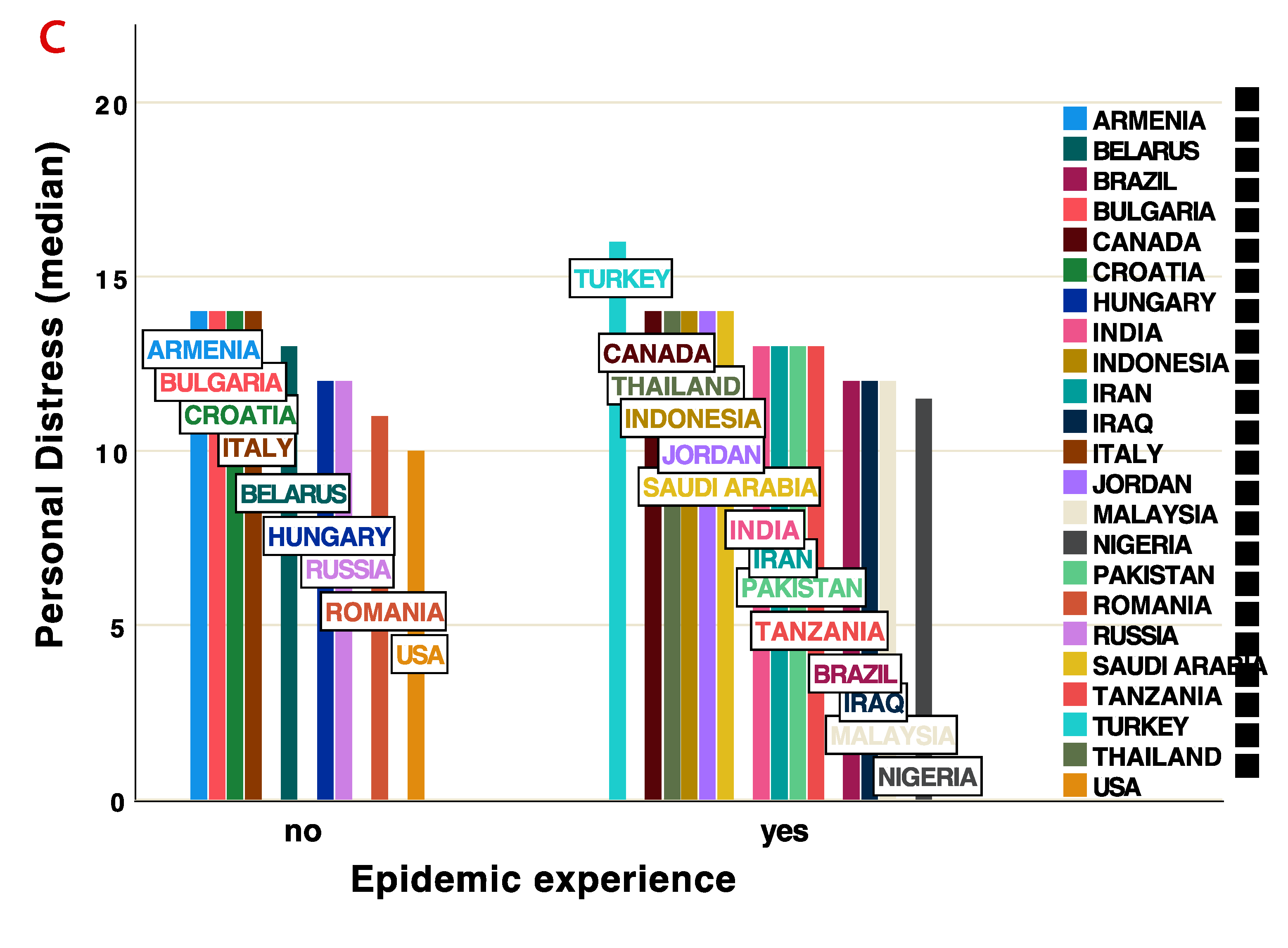

3.2.7. Association between Epidemic Experience and Empathy

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brooks, S.; Amlôt, R.; Rubin, G.J.; Greenberg, N. Psychological resilience and post-traumatic growth in disaster-exposed organisations: Overview of the literature. BMJ Mil. Health 2018, 166, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saladino, V.; Algeri, D.; Auriemma, V. The Psychological and Social Impact of Covid-19: New Perspectives of Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfattheicher, S.; Nockur, L.; Böhm, R.; Sassenrath, C.; Petersen, M.B. The Emotional Path to Action: Empathy Promotes Physical Distancing and Wearing of Face Masks during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bavel, J.J.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N.; et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvorsky, M.R.; Breaux, R.; Becker, S.P. Finding ordinary magic in extraordinary times: Child and adolescent resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prime, H.; Wade, M.; Browne, D.T. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkova, V.; Butovskaya, M.; Randall, A.K.; Zinurova, R.I. Predictors of anxiety in the COVID-19 pandemic from a global perspective: Data from 23 countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, D. The Altruism Question: Toward a Social-Psychological Answer; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, N. Emotion, Regulation, and Moral Development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2000, 51, 665–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.H. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Cat. Sel. Doc. Psychol. 1980, 10, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Decety, J.; Jackson, P. The Functional Architecture of Human Empathy. Behav. Cogn. Neurosci. Rev. 2004, 3, 71–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkin, J. The Empathic Civilization: The Race to Global Consciousness in a World in Crisis; Penguin Book: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vongas, J.G.; Hajj, R. The evolution of empathy and women’s precarious leadership appointments. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, M.C.; Park, H.S. The Effects of Corporate Elitism and Groupthink on Organizational Empathy in Crisis Situations. Public Relations Rev. 2021, 47, 101985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerami, C.; Santi, G.C.; Galandra, C.; Dodich, A.; Cappa, S.F.; Vecchi, T.; Crespi, C. Covid-19 Outbreak: Italy: Are We Ready for the Psychosocial and the Economic Crisis? Baseline Findings From the PsyCovid Study. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sassenrath, C.; Diefenbacher, S.; Siegel, A.; Keller, J. A person-oriented approach to hand hygiene behaviour: Emotional empathy fosters hand hygiene practice. Psychol. Health 2015, 31, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, A.R.; Burgmer, P. Perspective taking and automatic intergroup evaluation change: Testing an asso- ciative self-anchoring account. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 104, 786–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özer, Ö.; Özkan, O.; Budak, F.; Özmen, S. Does social support affect perceived stress? A research during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2020, 31, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietromonaco, P.R.; Overall, N.C. Applying relationship science to evaluate how the COVID-19 pandemic may impact couples’ relationships. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensley, P.L. Help for the helper: The psychophysiology of compassion fatigue and vicarious trauma. Bull. Menn. Clin. 2008, 72, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Gleichgerrcht, E.; Decety, J. Empathy in Clinical Practice: How Individual Dispositions, Gender, and Experience Moderate Empathic Concern, Burnout, and Emotional Distress in Physicians. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barello, S.; Graffigna, G. Caring for Health Professionals in the COVID-19 Pandemic Emergency: Toward an “Epidemic of Empathy” in Healthcare. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamothe, S.; Azimy, N.; Bazinet, L.; Couillard, C.; Britten, M. Interaction of green tea polyphenols with dairy matrices in a simulated gastrointestinal environment. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 2621–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, M.H. Empathy: A Social Psychological Approach; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lebowitz, M.S.; Dovidio, J.F. Implications of emotion regulation strategies for empathic concern, social attitudes, and helping behavior. Emotion 2015, 15, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Wang, X. The role of empathy in the mechanism linking parental psychological control to emotional reactivities to COVID-19 pandemic: A pilot study among Chinese emerging adults. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 168, 110399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambin, M.; Sharp, C. Relations between empathy and anxiety dimensions in inpatient adolescents. Anxiety Stress. Coping 2018, 31, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calandri, E.; Graziano, F.; Testa, S.; Cattelino, E.; Begotti, T. Empathy and Depression Among Early Adolescents: The Moderating Role of Parental Support. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, H.Z.; Price, J.L. The role of emotion regulation in the relationship between empathy and internalizing symptoms in college students. Ment. Health Prev. 2019, 13, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Groep, S.; Zanolie, K.; Green, K.H.; Sweijen, S.W.; Crone, E.A. A daily diary study on adolescents’ mood, empathy, and prosocial behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterhoff, B.; Palmer, C.A.; Wilson, J.; Shook, N. Adolescents’ Motivations to Engage in Social Distancing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Associations with Mental and Social Health. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagni, V.; Umilta’, A.; Iaria, G. Sleep Quality, Empathy, and Mood During the Isolation Period of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Canadian Population: Females and Women Suffered the Most. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depoux, A.; Martin, S.; Karafillakis, E.; Preet, R.; Wilder-Smith, A.; Larson, H. The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Corte, K.; Buysse, A.; Verhofstadt, L.L.; Roeyers, H.; Ponnet, K.; Davis, M.H. Measuring Empathic Tendencies: Reliability and Validity of the Dutch Version of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index. Psychol. Belg. 2007, 47, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Kang, S.-J. Exploring the Korean adolescent empathy using the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI). Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2020, 21, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.M.; Dufey, M.; Kramp, U. Testing the Psychometric Properties of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) in Chile. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2011, 27, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilet, A.-L.; Mella, N.; Studer, J.; Grühn, D.; Labouvie-Vief, G. Assessing dispositional empathy in adults: A French validation of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI). Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2013, 45, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tella, M.; Miti, F.; Ardito, R.B.; Adenzato, M. Social cognition and sex: Are men and women really different? Pers. Individ. Differ. 2020, 162, 110045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christov-Moore, L.; Simpson, E.; Coudé, G.; Grigaityte, K.; Iacoboni, M.; Ferrari, P.F. Empathy: Gender effects in brain and behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 46, 604–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilet, A.-L.; Evrard, C.; Galharret, J.-M.; Colombel, F. The Moderating Role of Education on the Relationship Between Perceived Stereotype Threat and False Memory in Aging. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 606249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, W.; Li, W.; Li, X. Age-related differences in affective and cognitive empathy: Self-report and performance-based evidence. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2018, 25, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosi, A.; Nola, M.; Lecce, S.; Cavallini, E. Prosocial behavior in aging: Which factors can explain age-related differences in social-economic decision making? Int. Psychogeriatrics 2019, 31, 1747–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beadle, J.N.; Sheehan, A.H.; Dahlben, B.; Gutchess, A.H. Aging, Empathy, and Prosociality. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2013, 70, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, P.E.; Henry, J.D.; Von Hippel, W. Empathy and social functioning in late adulthood. Aging Ment. Health 2008, 12, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, P.E.; Ruffman, T.; Rendell, P.G. Age-Related Differences in Social Economic Decision Making: The Ultimatum Game. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2012, 68, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchers, M.C.; Eli, M.; Haas, B.W.; Ereuter, M.; Ebischoff, L.; Emontag, C. Similar Personality Patterns Are Associated with Empathy in Four Different Countries. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, C.; Wei, M.; Wang, L. The role of individualism-collectivism in empathy: An exploratory study. Asian J. Couns. 2008, 15, 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Heinke, M.S.; Louis, W.R. Cultural Background and Individualistic-Collectivistic Values in Relation to Similarity, Perspective Taking, and Empathy. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 2570–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galang, C.M.; Johnson, D.; Obhi, S.S. Exploring the Relationship Between Empathy, Self-Construal Style, and Self-Reported Social Distancing Tendencies During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 588934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.D.; Rojjanasrirat, W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: A clear and user-friendly guideline. J. Eval. Clin. Pr. 2010, 17, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fülöp, E.; Devecsery, Á.; Hausz, K.; Kovács, Z.; Csabai, M. Relationship between empathy and burnout among psychiatric residents. Age 2011, 25, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Karyagina, T.D.; Budagovskaya, N.A.; Dubrovskaya, S.D. Adaptation of multyafactor questionnaire empathy M. Davis. Kosul’tativnaya psikhologiya i psikhoterapiya. Couns. Psychol. Psychother. 2013, 21, 202–227. [Google Scholar]

- Mestre, V.; Frias, M.D.; Samper, P. La medida de la empatia: Análisis del Interpersonal Reactivity Index (The measure of empathy: Analyses of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index). Psicothema 2004, 16, 225–260. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, R.; Guimaraes, L.; Camino, C.; Formiga, N.; Menezes, I. Studies on the dimensionality of empathy: Translation and adaptation of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI). Psico 2011, 42, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, M.D.C.; Qian, K.Z.; Wen, T.L.; Sankar, N. Empathy and Its Associated Factors Among Clinical Year Medical Students in Melaka-Manipal Medical College, Malaysia. JSSH 2020, 6, 174–187. [Google Scholar]

- Azahar, F.A.M.; Fakri, N.M.R.M.; Pa, M.N.M. Associations between Gender, Year of Study and Empathy Level with Attitudes towards Animal Welfare among Undergraduate Doctor of Veterinary Medicine Students in Universiti Putra Malaysia. Educ. Med. J. 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodabakhsh, M.; Mansuri, P. Relationship of Forgiveness and Empathy among Medical and Nursing Students. OFOGH-E-DANESH 2012, 18, 45–54. Available online: https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=278336 (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- Hosseinchari, M.; Fadakar, M.M. Investigating the effects of higher education on communication skills based on comparison of college and high school students. Daneshvar Raftar 2006, 12, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov, P.L.; Mateeva, N.L. A new research model for studying the effects of transformative factors of group dynamics on authenticity and empathy development. J. Int. Sci. Publ. Lang. Individ. Soc. 2012, 6, 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sofronieva, E. Measuring Empathy and Teachers’ Readiness to Adopt Innovations in Second Language Learning. In Early Years Second Language Education: International Perspectives on Theory and Practice; Mourão, S., Lourenço, M., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015; pp. 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Albiero, P.; Ingoglia, S.; Lo Coco, A. Contributo all’adattamento italiano dell’Interpersonal Reactivity Index. TPM Test. 2006, 13, 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Awad, F.B. Empathy and Criminal Behaviour of Aggressors at Detention Centre of Kendari, Indonesia. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2021, 58, 918–923. [Google Scholar]

- Afifi, M. Cross sectional study on lifelong learning’s determinants among medical students in RAK Medical & Health Sciences University, UAE. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2018, 68, 394–399. [Google Scholar]

- Tusyadiah, H. Hubungan Antara Pola Asuh Demokratis Orangtua Dengan Empati Pada Mahasiswa uin Suska. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitas Islam Negeri sultan Syarif Kasim Riau, Riau, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Covaci, A.; Constantinescu, P. The Romanian interpersonal reactivity index: Adaptation of an instrument for empathy research. In Proceedings of the Psiworld Conference, Bucharest, Romania, 27–30 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lupu, V. Is Christian Faith a Predictor for Empathy? Int. Conf. Knowl. Based Organ. 2018, 24, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Özbay, Y.; Yıldırım, H. Empati ile Bes Faktör Kişilik Modeli Arasındaki Ilişkinin Incelenmesi. In Ulusal Psikolojik Danışma Ve Rehberlik Kongresi’nde Sunulan Bildiri; Marmara Üniversitesi Atatürk Egĭtim Fakŭltesi: Istanbul, Turkey, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, N.; Aftab, M.A.; Haider, I.I.; Farhat, A. Educating tomorrow’s doctors: A cross sectional survey of emotional intelligence and empathy in medical students of Lahore. Pak. J. Med Sci. 2013, 29, 710–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mosalanejad, L.; Abdollahifar, S. The assessing empathy and relation with communication skills and compliance of professional ethics in medical students of Jahrom University of sciences: A pilot from south IRAN. FMEJ 2020, 10, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karyagina, T.; Kukhtova, N. M. Davis Empathy test: Content validity and adaptation in cross-cultural context. Couns. Psychol. Psychother. 2016, 24, 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyeza, D.M.; Savib, F. Empathy and self-efficacy, and resiliency: An exploratory study of counseling students in Turkey. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 5, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brazeau, C.M.; Schroeder, R.; Rovi, S.; Boyd, L. Relationships Between Medical Student Burnout, Empathy, and Professionalism Climate. Acad. Med. 2010, 85, S33–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojat, M.; Mangione, S.; Nasca, T.J.; Rattner, S.; Erdmann, J.B.; Gonnella, J.S.; Magee, M. An empirical study of decline in empathy in medical school. Med. Educ. 2004, 38, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, L. Five Ways the Coronavirus is Hitting Women in Asia. BBC News. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-51705199 (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- Contardi, A.; Imperatori, C.; Penzo, I.; Del Gatto, C.; Farina, B. The Association among Difficulties in Emotion Regulation, Hostility, and Empathy in a Sample of Young Italian Adults. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenova, O.; Apalkova, J.; Butovskaya, M. Sex Differences in Spatial Activity and Anxiety Levels in the COVID-19 Pandemic from Evolutionary Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambin, M.; Woźniak-Prus, M.; Sekowski, M.; Cudo, A.; Pisula, E.; Kiepura, E.; Kmita, G. Factors related to positive experiences in parent-child relationship during the COVID-19 lockdown. The role of empathy, emotion regulation, parenting self-efficacy and social support. PsyArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, L.W.; Gould, E.R.; Grimaldi, M.; Wilson, K.G.; Baffuto, G.; Biglan, A. First Things First: Parent Psychological Flexibility and Self-Compassion During COVID-19. Behav. Anal. Pr. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedenok, J.N.; Burkova, V.N. Social distancing as altruism in the context of the coronavirus pandemic: A cross-cultural study. Sib. Istor. Issled. 2020, 2, 6–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mækelæ, M.J.; Reggev, N.; Dutra, N.; Tamayo, R.M.; Silva-Sobrinho, R.A.; Klevjer, K.; Pfuhl, G. Perceived efficacy of COVID-19 restrictions, reactions and their impact on mental health during the early phase of the outbreak in six countries. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 7200644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Snell, J. Predicting a changing taste: Do people know what they will like? J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 1992, 5, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A.L.; Prosek, E.A.; Lankford, C.T. Predicting Empathy: The Role of Religion and Spirituality. J. Prof. Couns. Pr. Theory Res. 2014, 41, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Schoenrade, P.; Ventis, W.L. Religion and the Individual: A Social-Psychological Perspective; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Saroglou, V.; Pichon, I.; Trompette, L.; Verschueren, M.; Dernelle, R. Prosocial Behavior and Religion: New Evidence Based on Projective Measures and Peer Ratings. J. Sci. Study Relig. 2005, 44, 323–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, E.I.; Papanikolaou, F.; Epskamp, S. Mental Health and Social Contact During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Ecological Momentary Assessment Study. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branas-Garza, P.; Jorrat, D.A.; Alfonso, A.; Espin, A.M.; Garcıa, T.; Kovarik, J. Exposure to the Covid-19 pandemic and generosity. PsyArXiv 2020. Available online: https://osf.io/6ktuz (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- Zettler, I.; Schild, C.; Lilleholt, L.; Kroencke, L.; Utesch, T.; Moshagen, M.; Böhm, R.; Back, M.; Geukes, K. The role of personality in COVID-19 related perceptions, evaluations, and behaviors: Findings across five samples, nine traits, and 17 criteria. PsyArXiv 2020. Available online: https://osf.io/pkm2a (accessed on 5 August 2020).

| Country | Survey Language | Total N | Sex | Mean Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n) | Women (n) | (±SD) | |||

| ARMENIA | Armenian | 33 | 27 | 6 | 20.45 (±2.37) |

| BELARUS | Russian | 338 | 143 | 195 | 19.20 (±2.85) |

| BRAZIL | Portuguese | 515 | 82 | 430 | 38.80 (±13.78) |

| BULGARIA | Bulgarian | 322 | 129 | 193 | 28.34 (±8.75) |

| CANADA | English | 692 | 446 | 246 | 30.33 (±8.74) |

| CROATIA | English | 275 | 71 | 204 | 24.10 (±8.40) |

| HUNGARY | Hungarian | 235 | 35 | 198 | 31.95 (±11.84) |

| INDIA | English | 383 | 213 | 170 | 29.95 (±9.85) |

| INDONESIA | Indonesian | 930 | 504 | 424 | 32.05 (±12.09) |

| IRAN | Persian | 306 | 88 | 217 | 33.68 (±7.34) |

| IRAQ | Arabic | 173 | 88 | 85 | 35.03 (±10.63) |

| ITALY | Italian | 253 | 44 | 208 | 23.50 (±4.15) |

| JORDAN | Arabic | 449 | 121 | 328 | 33.68 (±10.52) |

| MALAYSIA | Malay | 1087 | 478 | 609 | 33.19 (±11.12) |

| NIGERIA | English | 316 | 214 | 102 | 34.09 (±11.24) |

| PAKISTAN | English | 484 | 212 | 272 | 27.06 (±11.11) |

| ROMANIA | Romanian | 269 | 42 | 226 | 36.22 (±10.94) |

| RUSSIA | Russian | 1903 | 486 | 1417 | 20.99 (±4.72) |

| SAUDI ARABIA | Arabic | 414 | 98 | 316 | 26.76 (±9.72) |

| TANZANIA | English | 341 | 185 | 156 | 23.95 (±4.25) |

| TURKEY | Turkish | 4717 | 1609 | 3093 | 27.57 (±10.84) |

| THAILAND | Thai | 300 | 49 | 250 | 32.82 (±13.00) |

| USA | English | 666 | 189 | 477 | 45.16 (±17.15) |

| TOTAL | 15,375 | 5553 | 9822 | 29.15 (±11.80) | |

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | df | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Perspective-Taking | 1 | 150.027 | <0.001 | 0.010 |

| Empathic Concern | 1 | 449.535 | <0.001 | 0.030 | |

| Personal Distress | 1 | 471.898 | <0.001 | 0.031 | |

| COUNTRY | Perspective-Taking | 22 | 72.617 | <0.001 | 0.098 |

| Empathic Concern | 22 | 143.856 | <0.001 | 0.177 | |

| Personal Distress | 22 | 50.210 | <0.001 | 0.070 | |

| Religion | Perspective-Taking | 6 | 2.383 | 0.027 | 0.001 |

| Empathic Concern | 6 | 6.156 | <0.001 | 0.003 | |

| Personal Distress | 6 | 3.416 | 0.002 | 0.001 | |

| COVID-19 is a threat to relatives | Perspective-Taking | 1 | 25.593 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Empathic Concern | 1 | 21.440 | <0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Personal Distress | 1 | 14.447 | <0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Living conditions | Perspective-Taking | 1 | 7.221 | 0.007 | 0.000 |

| Empathic Concern | 1 | 9.383 | 0.002 | 0.001 | |

| Personal Distress | 1 | 14.234 | <0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Involvement in voluntary activity | Perspective-Taking | 1 | 5.149 | 0.023 | 0.000 |

| Empathic Concern | 1 | .334 | 0.563 | 0.000 | |

| Personal Distress | 1 | 8.796 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | df | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Perspective-Taking | 1 | 219.083 | <0.001 | 0.014 |

| Empathic Concern | 1 | 545.523 | <0.001 | 0.035 | |

| Personal Distress | 1 | 376.272 | <0.001 | 0.024 | |

| Age | Perspective-Taking | 1 | 43.536 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Empathic Concern | 1 | 81.672 | <0.001 | 0.005 | |

| Personal Distress | 1 | 167.227 | <0.001 | 0.011 |

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | Df | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemic experience | Perspective-Taking | 1 | 14.889 | 0.002 | 0.498 |

| Empathic Concern | 1 | 9.928 | 0.007 | 0.398 | |

| Personal Distress | 1 | 1.580 | 0.228 | 0.095 | |

| IDVI | Perspective-Taking | 1 | 0.783 | 0.390 | 0.050 |

| Empathic Concern | 1 | 1.740 | 0.207 | 0.104 | |

| Personal Distress | 1 | 0.115 | 0.740 | 0.008 | |

| HDI | Perspective-Taking | 1 | 0.245 | 0.628 | 0.016 |

| Empathic Concern | 1 | 1.493 | 0.241 | 0.091 | |

| Personal Distress | 1 | 0.003 | 0.955 | 0.000 | |

| Social Support | Perspective-Taking | 1 | 0.140 | 0.714 | 0.009 |

| Empathic Concern | 1 | 0.507 | 0.487 | 0.033 | |

| Personal Distress | 1 | 0.382 | 0.546 | 0.025 | |

| Power Distance | Perspective-Taking | 1 | 3.287 | 0.090 | 0.180 |

| Empathic Concern | 1 | 5.601 | 0.032 | 0.272 | |

| Personal Distress | 1 | 0.192 | 0.668 | 0.013 | |

| Individualism | Perspective-Taking | 1 | 0.328 | 0.575 | 0.021 |

| Empathic Concern | 1 | 0.384 | 0.545 | 0.025 | |

| Personal Distress | 1 | 0.491 | 0.494 | 0.032 | |

| Total confirmed cases of COVID-19 per country | Perspective-Taking | 1 | 0.022 | 0.884 | 0.001 |

| Empathic Concern | 1 | 0.333 | 0.573 | 0.022 | |

| Personal Distress | 1 | 9.721 | 0.007 | 0.393 |

| Predictor | Dependent Variable | R2 | B | SE | Beta | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individualism | Perspective-Taking | 0.025 | 0.041 | 0.002 | 0.158 | 19.826 | <0.001 |

| Empathic Concern | 0.029 | 0.049 | 0.002 | 0.169 | 21.206 | <0.001 | |

| Personal Distress | 0.009 | −0.026 | 0.002 | −0.097 | −12.045 | <0.001 |

| Predictor | Dependent Variable | R2 | B | SE | Beta | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power Distance | Perspective-Taking | 0.141 | −0.045 | 0.024 | −0.375 | −1.853 | 0.078 |

| Empathic Concern | 0.135 | −0.056 | 0.031 | −0.388 | −1.811 | 0.084 | |

| Personal Distress | 0.005 | −0.005 | 0.016 | −0.070 | −0.322 | 0.751 |

| Predictor | Dependent Variable | R2 | B | SE | Beta | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total confirmed cases on 1 July 2020 | Perspective-Taking | 0.069 | 9.844 ×10−7 | 0.000 | 0.263 | 1.247 | 0.226 |

| Empathic Concern | 0.057 | 1.119 ×10−6 | 0.000 | 0.238 | 1.125 | 0.023 | |

| Personal Distress | 0.267 | −1.158 ×10−6 | 0.000 | −0.517 | −2.765 | 0.012 |

| Predictor | Dependent Variable | R2 | B | SE | Beta | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemic experience | Perspective-Taking | 0.537 | −3.238 | 0.655 | −0.733 | −4.940 | 00006 |

| Empathic Concern | 0.405 | −3.516 | 0.931 | −0.636 | −3.778 | 0.001 | |

| Personal Distress | 0.049 | 0.583 | 0.562 | 0.221 | 1.037 | 0.311 |

| Country | Year | Sample | N * | PT | EC | PD | Present Study | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT | EC | PD | ||||||||

| BELARUS | 2011 | 19—22 yy. helper students | 116m 92w | 21.69 23.74 | 21.72 24.59 | 19.38 22.20 | 16.45 17.36 | 15.74 18.02 | 10.37 14.01 | [72] |

| BRAZIL | 2011 | SD = 20.8 yy. | 250 | 26.15 27.57 | 26.14 29.09 | 20.69 23.66 | 19.40 19.41 | 20.63 22.30 | 12.76 15.92 | [55] |

| BULGARIA | 2015 | 19—25 yy. teacher students | 54 | 14.75 | 14.25 | 7.75 | 16.91 18.63 | 17.27 19.54 | 12.78 14.86 | [61] |

| CANADA | 2020 | 25.9 ± 10.5 yy. | 112m 459w | 14.6 16.1 | 17.3 20.8 | 11.0 8.8 | 16.27 17.82 | 15.95 17.67 | 13.28 14.41 | [31] |

| IRAN | 2020 | clinical students | 85 | 13.52 | 15.86 | 14.68 | 15.81 16.43 | 16.84 18.32 | 13.01 13.47 | [71] |

| ITALY | 2020 | SD = 42 yy. | 326m 827w | 18.23 | 20.39 | - | 18.16 19.50 | 19.57 21.14 | 12.73 14.15 | [15] |

| MALAYSIA | 2020 | medical students | 117 | 27 | 28.5 | 22.4 | 12.31 13.09 | 10.92 12.13 | 11.88 12.86 | [56] |

| PAKISTAN | 2013 | medical students | 132m 299w | 15.3 16.2 | 19.2 20.2 | 13.5 15.4 | 14.42 16.00 | 15.58 17.59 | 12.31 13.83 | [69] |

| ROMANIA | 2017 | Students | 43m 173w | 15.86 17.38 | 16.84 20.71 | - | 17.05 18.85 | 17.57 19.58 | 8.93 10.87 | [67] |

| RUSSIA | 2013 | 17—25 yy. psystudents | 101m 217w | 15.41 16.44 | 15.77 17.48 | 10.48 13.28 | 16.22 16.84 | 16.06 17.44 | 10.43 13.28 | [53] |

| TURKEY | 2010 | 17—21 yy. traniee students | 132 | 24.17 | 23.40 | 18.67 | 16.79 17.65 | 15.10 17.24 | 14.14 15.85 | [73] |

| USA | 1980 | psystudents | 579m 582w | 16.78 17.96 | 19.04 21.67 | 9.46 12.28 | 19.28 20.04 | 20.70 22.68 | 9.85 10.25 | [10] |

| 2016 | students 19.58 yy. | 92 | 17.46 | 19.11 | 12.74 | [46] | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Butovskaya, M.L.; Burkova, V.N.; Randall, A.K.; Donato, S.; Fedenok, J.N.; Hocker, L.; Kline, K.M.; Ahmadi, K.; Alghraibeh, A.M.; Allami, F.B.M.; et al. Cross-Cultural Perspectives on the Role of Empathy during COVID-19’s First Wave. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7431. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137431

Butovskaya ML, Burkova VN, Randall AK, Donato S, Fedenok JN, Hocker L, Kline KM, Ahmadi K, Alghraibeh AM, Allami FBM, et al. Cross-Cultural Perspectives on the Role of Empathy during COVID-19’s First Wave. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7431. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137431

Chicago/Turabian StyleButovskaya, Marina L., Valentina N. Burkova, Ashley K. Randall, Silvia Donato, Julija N. Fedenok, Lauren Hocker, Kai M. Kline, Khodabakhsh Ahmadi, Ahmad M. Alghraibeh, Fathil Bakir Mutsher Allami, and et al. 2021. "Cross-Cultural Perspectives on the Role of Empathy during COVID-19’s First Wave" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7431. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137431

APA StyleButovskaya, M. L., Burkova, V. N., Randall, A. K., Donato, S., Fedenok, J. N., Hocker, L., Kline, K. M., Ahmadi, K., Alghraibeh, A. M., Allami, F. B. M., Alpaslan, F. S., Al-Zu’bi, M. A. A., Biçer, D. F., Cetinkaya, H., David, O. A., Dural, S., Erickson, P., Ermakov, A. M., Ertuğrul, B., ... Zinurova, R. I. (2021). Cross-Cultural Perspectives on the Role of Empathy during COVID-19’s First Wave. Sustainability, 13(13), 7431. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137431