Communities on a Threshold: Climate Action and Wellbeing Potentialities in Scotland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Context and Definitions

2.1. Defining ‘Community’ in Relation to Sustainability and Resilience

2.2. Localising the Climate Discourse in Scotland: The Climate Challenge Fund

2.3. Scottish Policy Frameworks: From Behaviour Change to Wellbeing Goals

2.4. Definitions of Sustainable Wellbeing

2.5. Liminality in Relation to Social Transitions

3. Materials and Methods

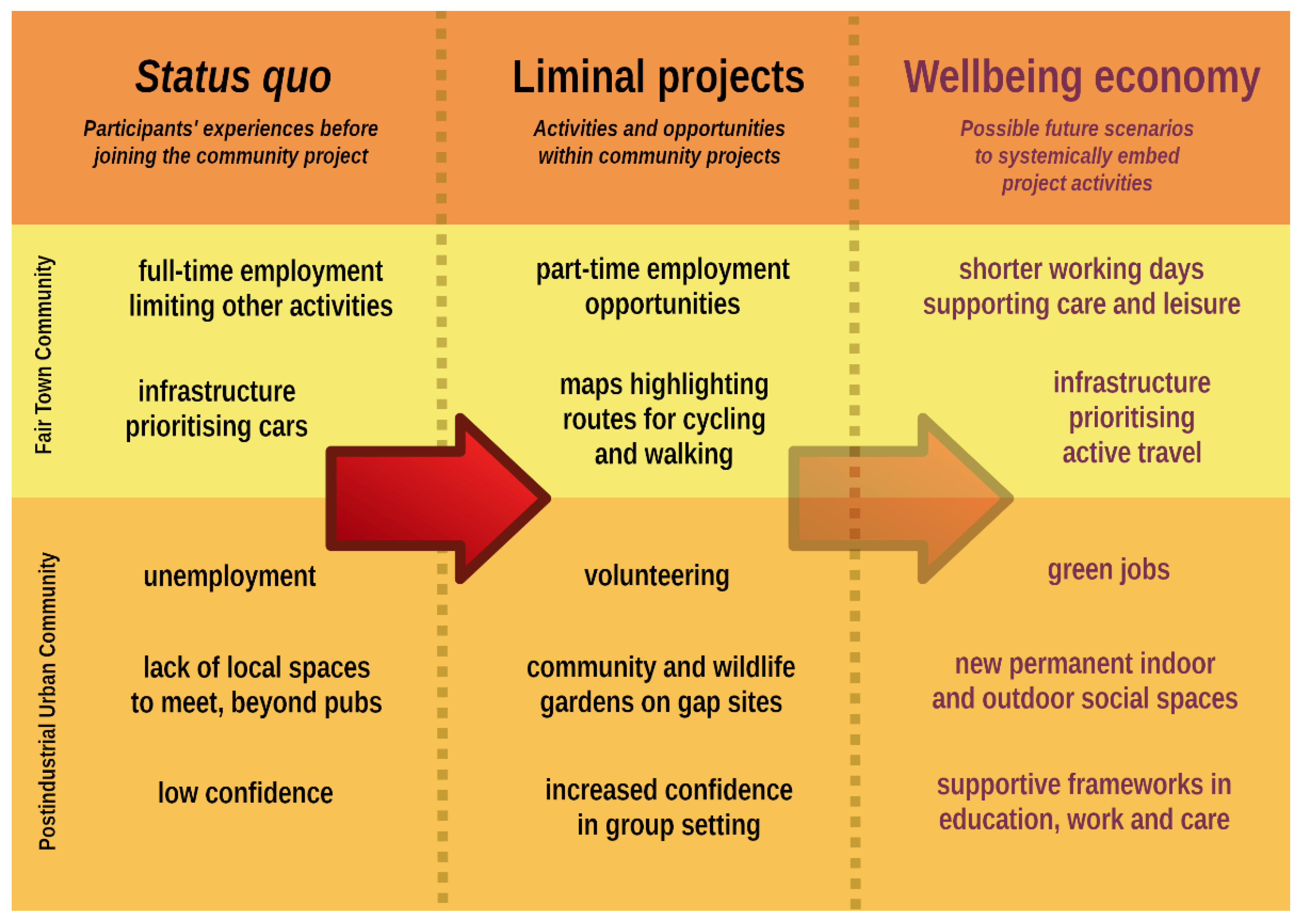

4. Community Projects as Liminal Catalysts of Wellbeing

4.1. Fair Town Community: Mapping Visions for a Resilient Region

“I see [FTC] as mainly being an organisation to help people out and to help them to travel by bus, by bike, by walking, to know how to make compost, to grow more food, and to do things that are nice to do—and not to necessarily help the environment, but also help the people who get so much more out of it if they are walking and cycling. Then they’ll meet their neighbours more, and it will be more of a friendly place.”(Melissa, staff member)

“I just can’t bring myself to say to people, yeah you should get the bus—because then you are responsible for people’s experience, and it’s nearly always a bad experience.”(Fiona, staff member)

“The Woodland Group I suppose primarily exists to look after the trees and the welfare of the trees, but then because it’s a community wood, we’ve obviously got a responsibility to the community to the woodland as a sort of recreation facility. So—we have dog walkers and joggers and kids out playing, and are looking after their interests as well.”(Catriona, Woodland Group volunteer)

Liminal Wellbeing in Fair Town Community

4.2. Postindustrial Urban Community: Fostering Health and Togetherness

“I can approach the kids and say, ‘what is it you’re gonnae lose?’ ‘I cannae afford to lose the face’. ‘You’re no’ losing face, you’re actually the bigger person, you’re learning a new skill, you’re learning to walk away.’ And it turns them away fae this self-destructive pattern, tae at that point they can start to be constructive, they can start planting trees, they can start learning how to weave willow, and cut wood and build bird-boxes and create footpaths out of just old muck and old pieces of hessian.”(Douglas, staff member)

“You know how people are, if they’re unemployed they can just sit and booze if they want, if they’ve got money. And I had money as I’d been working so... I could’ve boozed all day if I’d wanted and half of it I did. But then it’s best you sort of kind of keep your feet on the ground a bit, doing something. Just times of the day that you’re going to do something at that time of the day, you know. I suppose when you’re meeting people as well.”(Harry, volunteer)

“‘Unless you’re getting paid for it, what’s the point in daein’ it?’ Well, you are getting paid: you’re creating a better environment for yourself, you’re geein’ yourself somewhere nicer to live. And it’s about trying to explain that change in values to [interested but hesitant young people].”(Douglas, staff member)

“Wi’ the volunteering sector, people will just say that’s an excuse to do someone else’s job for them, but it’s not really. Because you wouldn’t be a part of that volunteering group if you didn’t want to be.”(Helen, volunteer)

Liminal Wellbeing in Postindustrial Urban Community

5. Community Projects as Fragments of a Wellbeing Economy

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; Masson-Delmotte, V.P., Zhai, H.-O., Pörtner, D., Roberts, J., Skea, P.R., Shukla, A., Pirani, W., Moufouma-Okia, C., Péan, R., et al., Eds.; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, E.; White, R.M.; Cox, E.; Bebbington, K.J.; Wilson, S. Craft and sustainable development: Reflections on Scottish craft and pathways to sustainability. Craft Des. Enq. 2012, 3, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.M. Sustainability research: A novel mode of knowledge generation to explore alternative ways for people and planet. In The Sustainable University: Progress and Prospects; Sterling, S., Maxey, L., Luna, H., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosberg, D. Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S.; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Prosperity without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet; Earthscan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzer, M.; Vetter, A. Degrowth/Postwachstum; Junius Verlag: Hamburg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Trebeck, K.; Williams, J. The Economics of Arrival. Ideas for a Grown Ep Economy; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. UN Report: Nature’s Dangerous Decline ‘Unprecedented’; Species Extinction Rates ‘Accelerating’. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/05/nature-decline-unprecedented-report/ (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Every-Palmer, S.; Jenkins, M.; Gendall, P.; Hoek, J.; Beaglehole, B.; Bell, C.; Williman, J.; Rapsey, C.; Stanley, J. Psychological distress, anxiety, family violence, suicidality, and wellbeing in New Zealand during the COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østertun Geirdal, A.; Ruffolo, M.; Leung, J.; Thygesen, H.; Price, D.; Bonsaksen, T.; Schoultz, M. Mental health, quality of life, wellbeing, loneliness and use of social media in a time of social distancing during the COVID-19 outbreak. A cross-country comparative study. J. Ment. Health 2021, 30, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook Lyndhurst and Ecometrica. Review of The Climate Challenge Fund; Scottish Government Social Research: Edinburgh, UK, 2011.

- Hilliam, A.; Moir, S.; Scott, L.; Clark, T.; Smith, I. Review of the Climate Challenge Fund. Changeworks/Scottish Government Social Research. 2015. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/research-and-analysis/2015/11/review-climate-challenge-fund/documents/review-climate-challenge-fund/review-climate-challenge-fund/govscot%3Adocument/00489046.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2020).

- Scottish Government. Health and Wellbeing as Fundamental as GDP. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/news/health-and-wellbeing-as-fundamental-as-gdp/ (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Sturgeon, N. Why Governments Should Prioritize Well-Being. 2019. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gJzSWacrkKo (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Büchs, M.; Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing. Challenges to Sustainable Welfare; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; Daly, L.; Fioramonti, L.; Giovannini, E.; Kubiszewski, I.; Mortensen, L.; Pickett, K.; Ragnarsdottir, K.; De Vogli, R.; Wilkinson, R. Modelling and measuring sustainable wellbeing in connection with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 130, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helne, T.; Hirvilammi, T. Wellbeing and Sustainability: A Relational Approach. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Economics Foundation. Well-Being Evidence for Policy: A Review. 2012. Available online: https://neweconomics.org/2012/04/well-evidence-policy-review (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- O’Riordan, T. Sustainability for wellbeing. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2013, 6, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, K.; Konstantakos, L.; Carrasco, A.; Carmona, L.G. Sustainable Development, Wellbeing and Material Consumption: A Stoic Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turner, V.W. Frame, Flow and Reflection: Ritual and Drama as Public Liminality. Jpn. J. Relig. Stud. 1979, 6, 465–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mälksoo, M. The Challenge of Liminality for International Relations Theory. Rev. Int. Stud. 2012, 38, 481–494. Available online: www.jstor.org/stable/41485559 (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Banks, S. The concept of “Community Practice”. In Managing Community Practice: Principles, Policies and Programmes; Banks, S., Butcher, H., Henderson, P., Robertson, J., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B.R.O. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism; Rev. Verso: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gusfield, J.R. Community—A Critical Response; Oxford: Basil Blackwell, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H. Sustainable Communities: The Potential for Eco-Neighbourhoods; Earthscan: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Aiken, G. Common Sense Community? The Climate Challenge Fund’s Official and Tacit Community Construction. Scott. Geogr. J. 2014, 13, 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R. Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Community: Seeking Safety in an Insecure World; Blackwell, Cambridge; Polity: Malden, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Moloney, S.; Horne, R.E.; Fien, J. Transitioning to low carbon communities—From behaviour change to systemic change: Lessons from Australia. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7614–7623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heiskanen, E.; Johnson, M.; Robinson, S.; Vadovics, E.; Saastamoinen, M. Low carbon communities as a context for individual behavioural change. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7586–7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; Martinelli, F.; Swyngedouw, E.; González, S. Towards alternative model(s) of local innovation. Urban. Stud. 2005, 42, 1969–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Grassroots Innovations for Sustainable Development: Towards a New Research and Policy Agenda. Environ. Politics 2007, 16, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, P. The politics of climate activism in the UK: A social movement analysis. Environ. Plan. A 2020, 43, 1581–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winther, A. Community sustainability: A holistic approach to measuring the sustainability of rural communities. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2017, 24, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, L.H.; Holling, C.S. Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wilding, N. Exploring Community Resilience in Times of Rapid Change; Carnegie UK Trust: Dunfermline, Scotland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerricks, S.; Mackenzie, E. Towards critical resilience: Political and social dimensions of work in community projects. Justice Spat./Spat. Justice 2021, Forthcoming. Justice Spat./Spat. Justice 2021. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Creamer, E. The double-edged sword of grant funding: A study of community-led climate change initiatives in remote rural Scotland. Local Environ. Online Ed. 2014, 20, 981–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. Climate Change (Scotland) Act. 2009. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2009/12/pdfs/asp_20090012_en.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Measham, T.G.; Preston, B.L.; Smith, T.F.; Brooke, C.; Gorddard, R.; Withycombe, G.; Morrison, C. Adapting to climate change through local municipal planning: Barriers and challenges. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2011, 16, 889–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keep Scotland Beautiful. Climate Challenge Fund. 2021. Available online: https://www.keepscotlandbeautiful.org/climate-change/climate-challenge-fund/ (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Bolger, C.; Allen, S.J. Cui bono: The Scottish Climate Challenge Fund and community benefits. Local Environ. 2012, 18, 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanen, T.; Banister, D.; Anable, J. Rethinking habits and their role in behaviour change: The case of low-carbon mobility. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 24, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, N.; Gatersleben, B.; Uzzell, D. Self-identity threat and resistance to change: Evidence from regular travel behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Webb, J. Climate Change and Society: The Chimera of Behaviour Change Technologies. Sociology 2012, 46, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Prillwitz, J. A smarter choice? Exploring the behaviour change agenda for environmentally sustainable mobility. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2014, 32, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, P.; Ward, S. British Environmental Policy and Europe: Politics and Policy in Transition; Global Environmental Change Series; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, A. Soil and Soul: People Versus Corporate Power; Aurum Press: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wightman, A. The Poor Had no Lawyers: Who Owns Scotland (and How They Got It); Birlinn: Edinburgh, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Government. Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2015/6/pdfs/asp_20150006_en.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Oxford English Dictionary. Entry of ‘Liminal’. 2018. Available online: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/liminal (accessed on 11 February 2018).

- Van Gennep, A. The Rites of Passage; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V.W. Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites of Passage. In Betwixt and Between: Thresholds of Masculine and Feminine Initiation; Mahdi, L.C., Foster, S., Little, M., Eds.; Open Court Publishing Co: Chicago, IL, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V.W. Revelation and Divination in Ndembu Ritual; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, Greece, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V.W. Liminal to Liminoid, in Play, Flow, and Ritual: An Essay in Comparative Symbology. Rice Inst. Pam. Rice Univ. Stud. 1974, 60, 53–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ince, A. In the Shell of the Old: Anarchist Geographies of Territorialisation. Antipode 2012, 44, 1645–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stroh, M. Qualitative Interviewing. In Research Training for Social Scientists; Burton, D., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, D. The Use of Case Studies in Social Science Research. In Research Training for Social Scientists; Burton, D., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2016. Available online: http://simd.scot/2016/#/simd2016/BTTTFTT/9/-4.0000/55.9000/ (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Van de Grift, E.; Vervoort, J.; Cuppen, E. Transition Initiatives as Light Intentional Communities: Uncovering Liminality and Friction. Sustainability 2017, 9, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FTC. [FTC] Action Plan, [FTC] 2025. 2011. Available online: https://www.ftc.gov (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Eizenberg, E. Actually Existing Commons: Three Moments of Space of Community Gardens in New York City. Antipode 2012, 44, 764–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, C.; Maye, D.; Pearson, D. Developing “community” in community gardens. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedli, L. What we’ve tried, hasn’t worked: The politics of assets based public health. Crit. Public Health 2012, 23, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennett, R. Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation; Allen Lane: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, A.; Newton, J.; Middleton, J.; Marsden, T. Reconnecting skills for sustainable communities with everyday life. Environ. Plan. A 2011, 43, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, D.; Lister, S.; Hadfield, P.; Winlow, S.; Hall, S. Receiving shadows: Governance and liminality in the night-time economy. Br. J. Sociol. 2000, 51, 701–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, K. Eigensinnige Beheimatungen. Gemeinschaftsgärten als Orte des Widerstands gegen die neoliberale Ordnung. In Urban Gardening: Über Die Rückkehr Der Gärten in Die Stadt; Müller, C., Ed.; Oekom: München, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, R.; Pickett, K. The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone; Penguin: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh, B.; Boland, P. Community asset transfer and strategies of local accumulation. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2017, 20, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gatersleben, B.; Uzzell, D. Affective Appraisals of the Daily Commute: Comparing Perceptions of Drivers, Cyclists, Walkers and Users of Public Transport. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Nazelle, A.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Antó, J.M.; Brauer, M.; Briggs, D.; Braun-Fahrlander, C.; Cavill, N.; Cooper, A.R.; Desqueyroux, H.; Fruin, S. Improving health through policies that promote active travel: A review of evidence to support integrated health impact assessment. Environ. Int. 2011, 37, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellbeing Economy Alliance. Replacing GDP with “Girls on Bikes”. 2019. Available online: https://wellbeingeconomies.film/2019/08/28/replacing-gdp-with-girls-on-bikes/ (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Russell, S.L.; Greenaway, A.; Carswell, F.; Weaver, S. Moving beyond “mitigation and adaptation”: Examining climate change responses in New Zealand. Local Environ. 2013, 19, 767–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, B.; Dooris, M.; Haluza-Delay, R. Securing “supportive environments” for health in the face of ecosystem collapse: Meeting the triple threat with a sociology of creative transformation. Health Promot. Int. 2011, 26, ii202–ii215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Noordwijk, M.; Hoang, M.H.; Neufeldt, H.; Öborn, I.; Yatich, T. How Trees and People Can Co-Adapt to Climate Change: Reducing Vulnerability Through Multi- Functional Agroforestry Landscapes; World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF): Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Howarth, C.; Bryant, P.; Corner, A.; Fankhauser, S.; Gouldson, A.; Whitmarsh, L.; Willis, R. Building a Social Mandate for Climate Action: Lessons from COVID-19. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 76, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meyerricks, S.; White, R.M. Communities on a Threshold: Climate Action and Wellbeing Potentialities in Scotland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7357. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137357

Meyerricks S, White RM. Communities on a Threshold: Climate Action and Wellbeing Potentialities in Scotland. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7357. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137357

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeyerricks, Svenja, and Rehema M. White. 2021. "Communities on a Threshold: Climate Action and Wellbeing Potentialities in Scotland" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7357. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137357

APA StyleMeyerricks, S., & White, R. M. (2021). Communities on a Threshold: Climate Action and Wellbeing Potentialities in Scotland. Sustainability, 13(13), 7357. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137357