Ecofeminism and Natural Resource Management: Justice Delayed, Justice Denied

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Literature on Different Forms of Women Exploitation in the Mining Sector

1.2. The Literature on the Role of Women’s Autonomy in Promoting Resource Market through the Decision-Making Process

1.3. The Literature on Women Participation in Environmental Protection

1.4. Research Contribution(s), Research Question(s), and Objectives of the Study

- (i)

- To analyze the different roles of women’s autonomy in the mining sector.

- (ii)

- To examine the impact of women’s ecological footprints, access to finance, and environmental protection on the mineral resource sector, and

- (iii)

- To observe the role of women’s socio-economic autonomy on the resource conservation agenda.

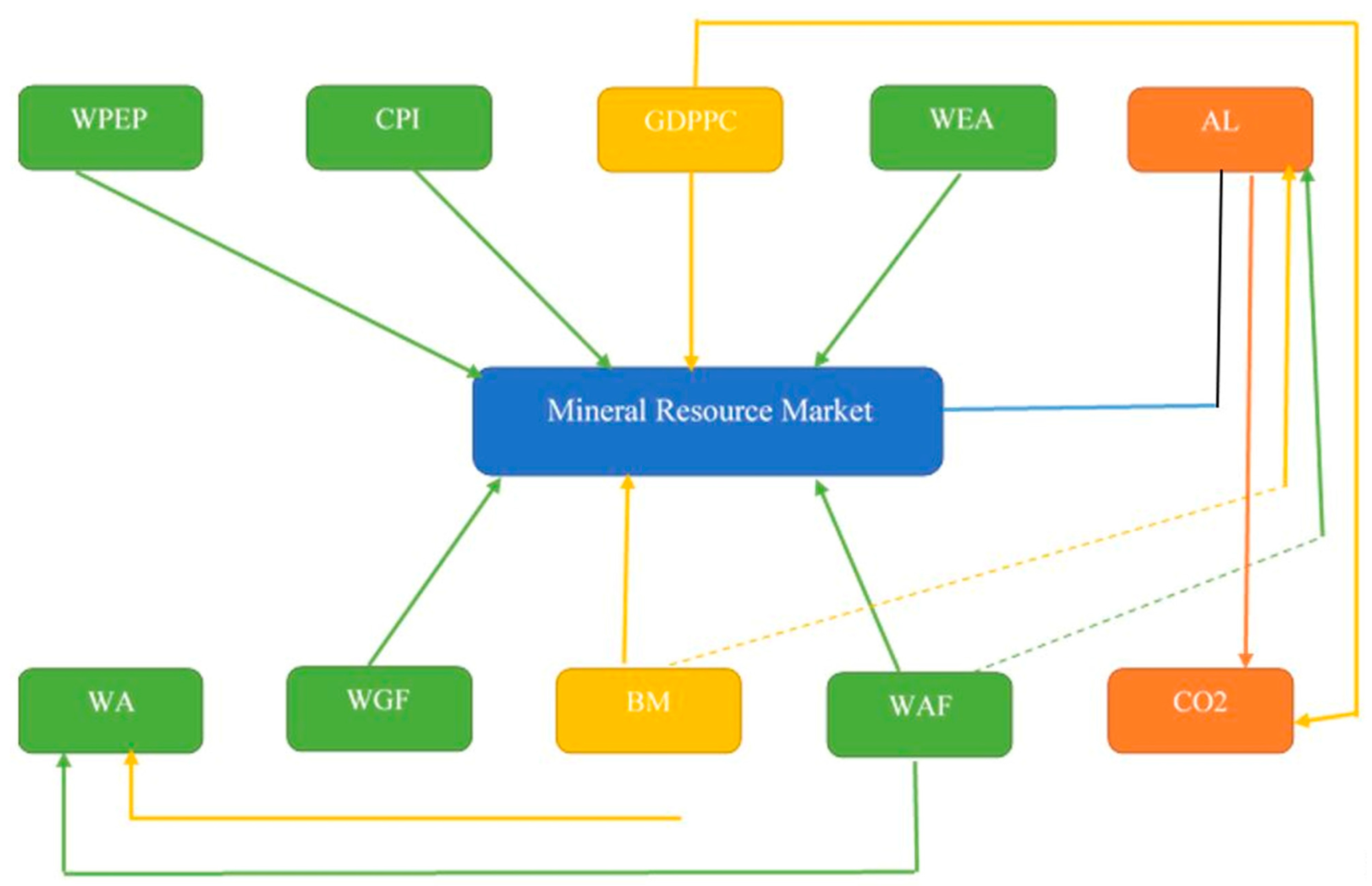

2. Materials and Methods

- (i)

- Women’s Green Ecological Footprints (WGF): Gender differences are mostly visible in different consumption patterns with different carbon footprints. Women are generally environmentally friendly and love to take care of their natural surroundings. Thus, women leave a smaller ecological footprint than males [46,47]. The current study calculated women’s ecological footprints based on total ecological footprints relative to women’s autonomy index. The average 10-year data of arable land in hectares (a proxy for ecological footprints) relative to the women’s autonomy index is used for the years 1975–1984, 1985–1994, 1995–2004, and 2005–2014, while 5-years average data is used for the years 2015–2019, i.e.,where AL shows arable land and WA shows women’s autonomy.

- (ii)

- Women’s Access to Finance (WAF): The women’s role in economic development viewed in the earlier studies, which controlled by financial indicators [48,49], entrepreneurial activities [50], and access to healthcare services [51]. The unlocking of women’s potential in extractive industries leads them to optimize resource allocations. The study calculated 10-years and 5-years average value of money supply and women’s autonomy index to calculate women access to finance in the mining sector, i.e.,

- (iii)

- Women’s Participation in Environmental Protection (WPEP): Women’s role in a sustainable environment is viewed in the resource conservation agenda [52], thus it is required to calculate WPEP in terms of carbon emissions and women’s autonomy index to access women role in carbon mitigation in the mining sector, i.e.,

- (iv)

- Women’s Economic Autonomy (WEA) refers to a situation where women feel safe and secure in the working environment and household affairs and get autonomy in conserve resource capital. The study calculated this factor by interaction term of country’s per capita income and women’s autonomy index that gives synergetic impact to assess women role in economic decisions, i.e.,

- (i)

- All the variables have a standard order of integration, and

- (ii)

- The candidate variables have a different integration of order.

- (i)

- Engle-Granger two-step cointegration process

- (ii)

- Johanson cointegration, and

- (iii)

- ARDL cointegration procedure.

- (i)

- OLS regression techniques for I(0) variables

- (ii)

- Instrumental variables where known endogeneity problem exists

- (iii)

- Regression techniques for I(1) variables, and

- (iv)

- Regression technique for a mixture of I(0) and I(1) series

- (i)

- Feedback Causality

- (ii)

- One-way causality

- (iii)

- (xv)Reverse causality, and

- (iv)

- No Causality

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldakhil, A.M.; Nassani, A.A.; Zaman, K. The role of technical cooperation grants in mineral resource extraction: Evidence from a panel of 12 abundant resource economies. Resour Policy 2020, 69, 101822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaggwa, M. Interventions to promote gender equality in the mining sector of South Africa. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020, 7, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.O.; Ola, O.; Buchenrieder, G. Does an agroforestry scheme with payment for ecosystem services (PES) economically empower women in sub-Saharan Africa? Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangaroo-Pillay, S.; Botha, D. An exploration of women’s workplace experiences in the South African mining industry. J. South. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2020, 120, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Fast Facts: Statistics on Violence Against Women and Girls, UN Women. 2010. Available online: https://www.endvawnow.org/en/articles/299-fast-facts-statistics-on-violence-against-women-and-girls-.html (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- World Bank. WASH Poor in a Water-Rich Country. In A Diagnostic of Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, and Poverty in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Executive Summary; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lugova, H.; Samad, N.; Haque, M. Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Among Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Post-Conflict Scenario. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nachega, J.B.; Mbala-Kingebeni, P.; Otshudiema, J.; Mobula, L.M.; Preiser, W.; Kallay, O.; Ahuka-Mundeke, S. Responding to the challenge of the dual COVID-19 and Ebola epidemics in the Democratic Republic of Congo—Priorities for achieving control. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseboom, T.J. Why achieving gender equality is of fundamental importance to improve the health and well-being of future generations: A DOHaD perspective. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2020, 11, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khosla, R.; Banerjee, J.; Chou, D.; Say, L.; Fried, S.T. Gender equality and human rights approaches to female genital mutilation: A review of international human rights norms and standards. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Goal 5: Achieve Gender Equality and Empower All Women and Girls. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/ (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Botha, D. Barriers to career advancement of women in mining: A qualitative analysis. S. Afr. J. Empl. Relat. 2017, 41, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pactwa, K. Is There a Place for Women in the Polish Mines?—Selected Issues in the Context of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mugo, D.; Ondieki-Mwaura, F.; Omolo, M. The Social-Cultural Context of Women Participation In Artisanal And Small-Scale Mining: Case Of Taita Taveta Region Of Kenya. Afr. J. Emerg. Issues 2020, 2, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bashwira, M.R.; van der Haar, G. Necessity or choice: Women’s migration to artisanal mining regions in eastern DRC. Can. J. Afr. Stud. 2020, 54, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orleans-Boham, H.; Sakyi-Addo, G.B.; Tahiru, A.; Amankwah, R.K. Women in artisanal mining: Reflections on the impacts of a ban on operations in Ghana. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020, 7, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, V. Financial inclusion for women and men in artisanal gold mining communities: A case study from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020, 7, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thankian, K. Factors Affecting Women’s Autonomy in Household Decision-Making among Married Women in Zambia. J. Sci Res. Rep. 2020, 26, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.; Singh, S.; Unni, J. Markets and Spillover Effects of Political Institutions in Promoting Women’s Empowerment: Evidence from India. Fem. Econ. 2020, 26, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, C.; Rammohan, A. Rural women’s empowerment and children’s food and nutrition security in Bangladesh. World Dev. 2019, 124, 104648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S. Women’s entrepreneurship and social capital: Exploring the link between the domestic sphere and the marketplace in Pakistan. Strateg. Chang. 2020, 29, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, J.; Marques, C.S.; Braga, A.; Ratten, V. A systematic review of women’s entrepreneurship and internationalization literature. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 61, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Ravenscroft, N.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P. Governance, gender and the appropriation of natural resources: A case study of ‘left-behind’women’s collective action in China. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019, 32, 382–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramstetter, L.; Habersack, F. Do women make a difference? Analysing environmental attitudes and actions of Members of the European Parliament. Environ. Politics 2020, 29, 1063–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birindelli, G.; Iannuzzi, A.P.; Savioli, M. The impact of women leaders on environmental performance: Evidence on gender diversity in banks. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1485–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiRienzo, C.E.; Das, J. Women in government, environment, and corruption. Environ. Dev. 2019, 30, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Deng, C. Does women’s political empowerment matter for improving the environment? A heterogeneous dynamic panel analysis. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, E.; Lyons, H.; Stephens, J.C. Women’s leadership in renewable transformation, energy justice and energy democracy: Redistributing power. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 57, 101233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Guo, H.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, H.; Qi, W. The double effects of female executives’ participation on corporate sustainable competitive advantage through unethical environmental behavior and proactive environmental strategy. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 2324–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Sun, X. Toward gender sensitivity: Women and climate change policies in China. Int. Fem. J. Politics 2020, 22, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benya, A.P. Women in Mining: A Challenge to Occupational Culture in Mines. Doctoral Dissertation, Faculty of Social Science and Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mercier, L.; Gier, J. Reconsidering women and gender in mining. Hist. Compass 2007, 5, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, M.S.; Karkada, S.N.; Somayaji, G. Factors associated with health-related quality of life among Indian women in mining and agriculture. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Botha, D.; Cronjé, F. Women in mining: A conceptual framework for gender issues in the South African mining sector. S. Afr. J. Labour Relat. 2015, 39, 10–37. [Google Scholar]

- Botha, D. Women in mining still exploited and sexually harassed. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lahiri-Dutt, K. Do Women Have a Right to Mine? Can. J. Women Law 2019, 31, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Goltz, J.; Barnwal, P. Mines: The local wealth and health effects of mineral mining in developing countries. J. Dev. Econ. 2019, 139, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, M. Mining and Social Capital: A Micro-analysis from Odisha, India. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. 2020, 29, 100–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegenast, T.; Beck, J. Mining, rural livelihoods and food security: A disaggregated analysis of sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev. 2020, 130, 104921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, N.B.R.; da Silva, E.A.; Neto, J.M.M. Sustainable development goals in mining. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, D.; Rutherford, B.; Stewart, J.; Côté, G.E.; Sebina-Zziwa, A.; Kibombo, R.; Lebert, J. Gender and artisanal and small-scale mining: Implications for formalization. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2019, 6, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashwira, M.R.; Cuvelier, J. Women, mining and power in southeastern Democratic Republic of Congo: The case of Kisengo. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2019, 6, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirons, M. How the Sustainable Development Goals risk undermining efforts to address environmental and social issues in the small-scale mining sector. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 114, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, S. Digging for Rights: How Can International Human Rights Law Better Protect Indigenous Women from Extractive Industries? Can. J. Women Law 2019, 31, 58–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsson-Latham, G. Initial study of lifestyles, consumption patterns, sustainable development and gender: Do women leave a smaller ecological footprint than men? In Report from the Swedish Ministry of Sustainable Development; Ministry of Sustainable Development: Stockholm, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Toro, F.; Serrano, M.; Guillen, M. Who Pollutes More? Gender Differences in Consumptions Patterns, Research Institute of Applied Economics Working Paper 2019/06 1/48 pág. 2019. Available online: http://www.ub.edu/irea/working_papers/2019/201906.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Hendriks, S. The role of financial inclusion in driving women’s economic empowerment. Dev. Pract. 2019, 29, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bent, B.B. The Impact of Microfinance on Poverty Reduction and Women Empowerment. In Rais Collective Volume–Economic Science; Scientia Moralitas Research Institute: Frankfurt, Germany, 2019; pp. 72–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D. Identifying women’s entrepreneurial barriers and empowering female entrepreneurship worldwide: A fuzzy-set QCA approach. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 905–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anindya, K.; Lee, J.T.; McPake, B.; Wilopo, S.A.; Millett, C.; Carvalho, N. Impact of Indonesia’s national health insurance scheme on inequality in access to maternal health services: A propensity score matched analysis. J. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 010429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimi, M.; Suleiman, R.M.; Odipe, O.E.; Tolulope, S.J.; Modupe, O.; Olalekan, A.S.; Christianah, M.B. Women Role in Environmental Conservation and Development in Nigeria. Ecol. Conserv. Sci. 2019, 1, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J. Appl. Econom. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.L.; Samra, J.S.; Mittal, S.P. Rural women and conservation of natural resources: Traps and opportunities. Gend. Technol. Dev. 1998, 2, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mago, P.; Gunwal, I. Role of Women in Environment Conservation. 2019. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3368066 (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- Singh, S.; Dixit, S. Diverse Role of Women for Natural Resource Management in India. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2020, 38, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.S.; Solomon, J. Challenges and supports for women conservation leaders. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2019, 1, e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asi, Y.M.; Williams, C. Equality through innovation: Promoting women in the workplace in low-and middle-income countries with health information technology. J. Soc. Issues 2020, 76, 721–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Munir, I.U.; Hyder, S.; Nassani, A.A.; Abro, M.M.Q.; Zaman, K. Sustainable food production, forest biodiversity and mineral pricing: Interconnected global issues. Resour. Policy 2020, 65, 101583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassani, A.A.; Awan, U.; Zaman, K.; Hyder, S.; Aldakhil, A.M.; Abro, M.M.Q. Management of natural resources and material pricing: Global evidence. Resour. Policy 2019, 64, 101500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.U.R.; Islam, T.; Yousaf, S.U.; Zaman, K.; Shoukry, A.M.; Sharkawy, M.A.; Hishan, S.S. The impact of financial development indicators on natural resource markets: Evidence from two-step GMM estimator. Resour. Policy 2019, 62, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Altinoz, B.; Tzeremes, P. The analysis of ‘Financial Resource Curse’ hypothesis for developed countries: Evidence from asymmetric effects with quantile regression. Resour. Policy 2020, 68, 101773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.U.R.; Zaman, K.; Usman, B.; Nassani, A.A.; Aldakhil, A.M.; Abro, M.M.Q. Financial management of natural resource market: Long-run and inter-temporal (forecast) relationship. Resour. Policy 2019, 63, 101452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Sengupta, T. Impact of natural resource rents on human development: What is the role of globalization in Asia Pacific countries? Resour. Policy 2019, 63, 101413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Khan, K.B.; Anser, M.K.; Nassani, A.A.; Abro, M.M.Q.; Zaman, K. Dynamic interaction between financial development and natural resources: Evaluating the ‘Resource curse’ hypothesis. Resour. Policy 2020, 65, 101566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, S.; Benshaul-Tolonen, A. Structural Transformation, Extractive Industries and Gender Equality. 2019. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3464290 (accessed on 19 December 2020).

- Ibrahim, A.F.; Rutherford, B.; Buss, D. Gendered “choices” in Sierra Leone: Women in artisanal mining in Tonkolili District. Can. J. Afr. Stud. 2020, 54, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, A.; Maleksaeidi, H. Pro-environmental behavior of university students: Application of protection motivation theory. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Nozawa, W.; Managi, S. The role of women on boards in corporate environmental strategy and financial performance: A global outlook. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2044–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Islam, M.; Managi, S. Green growth and pro-environmental behavior: Sustainable resource management using natural capital accounting in India. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 145, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, N.; Grundmann, P. Home-cooked energy transitions: Women empowerment and biogas-based cooking technology in Pakistan. Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnamawati, I.; Adnyani, N. Performance evaluation of microfinance institutions and local wisdom-based management concept. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, B.; Bergh, S.I. Why women’s traditional knowledge matters in the production processes of natural product development: The case of the Green Morocco Plan. In Women’s Studies International Forum; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 77, p. 102275. [Google Scholar]

- Bleischwitz, R.; Dittrich, M.; Pierdicca, C. Coltan from Central Africa, international trade and implications for any certification. Res. Policy 2012, 37, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hilson, G.; Van Bockstael, S.; Sauerwein, T.; Hilson, A.; McQuilken, J. Artisanal and small-scale mining, and COVID-19 in sub-Saharan Africa: A preliminary analysis. World Dev. 2021, 139, 105315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterman, A.; Schwab, B.; Roy, S.; Hidrobo, M.; Gilligan, D.O. Measuring women’s decision making: Indicator choice and survey design experiments from cash and food transfer evaluations in Ecuador, Uganda and Yemen. World Dev. 2021, 141, 105387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPU. Women in Politics: 2021; Inter-Parliamentary Union: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.ipu.org/women-in-politics-2021 (accessed on 13 June 2021).

| Factors | Variables | Symbol | Measurement | Data Source | Expected Sign |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | |||||

| Resource Market | Mineral Resource Rents | MRR | % of GDP | World Bank (2020) | ----- |

| Independent Variables | |||||

| Women Freedom | Women’s Autonomy | WA | Women Business and the Law Index Score (scale 1–100) | World Bank (2020) | Positive |

| Ecological Footprints | Arable Land | AL | Hectares | World Bank (2020) | Negative |

| Green Footprints | Women Green Footprints | WGF | The relative contribution of 10 years average value of AL into WA | Author’s Construct | Positive |

| Financial Sector | Broad Money Supply | BM | % of GDP | World Bank (2020) | Positive/Negative |

| Green Finance | Women Access to Finance | WAF | The relative contribution of 10 years average value of BM into WA | Author’s Construct | Positive |

| Environmental Degradation | CO2 Emissions | CO2 | Metric tons per capita | World Bank (2020) | Negative |

| Environmental Protection | Women Participation in Environmental Protection | WPEP | The relative contribution of 10 years average value of CO2 into WA | Author’s Construct | Positive |

| Changes in Price Level- GDP deflator | Women Household Affairs (Proxy variable) | WHA | Annual % | World Bank (2020) | Negative |

| Economic Growth | GDP per capita | GDPPC | Constant of 2010 US$ | World Bank (2020) | Positive/Negative |

| Women Economic Development | Women’s Economic Autonomy | WEA | The interaction term of WA × GDPPC | Author’s Construct | Positive |

| Time Period | Average WA Index Value (Low Autonomy 1 to High Autonomy 100) | Average WGF (Hectares) | Average WAF (% of GDP) | Average WPEP (Metric Tons per Capita) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975–1984 | 23.10 | 286,558.4 | 0.695 | 0.006 |

| 1985–1994 | 24.85 | 269,497.0 | 0.503 | 0.004 |

| 1995–2004 | 29.98 | 223,482.3 | 0.170 | 0.001 |

| 2005–2014 | 42.50 | 204,261.1 | 0.212 | 0.0009 |

| 2015–2019 | 62.50 | 210,976.7 | 0.102 | 0.0004 |

| Methods | MRR | WA | AL | WGF | BM | WAF | CO2 | WPEP | CPI | GDPPC | WEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 6.143 | 33.653 | 6,764,556 | 242,063.8 | 10.906 | 0.373 | 0.071 | 0.003 | 896.667 | 539.442 | 16,412.93 |

| Maximum | 19.505 | 78.800 | 7,100,000 | 288,744.6 | 72.372 | 3.132 | 0.146 | 0.006 | 26,765.8 | 1048.551 | 33,382.85 |

| Minimum | 0.143 | 23.100 | 6,545,000 | 199,090.7 | 2.857 | 0.095 | 0.016 | 0.0004 | 0.993 | 276.055 | 7757.172 |

| Std. Dev. | 5.926 | 13.661 | 170,646 | 33,769.75 | 10.426 | 0.464 | 0.048 | 0.002 | 4020.32 | 245.612 | 5812.232 |

| Skewness | 0.957 | 1.611 | 1.259 | 0.183 | 4.805 | 4.930 | 0.438 | 0.489 | 6.127 | 0.557 | 0.682 |

| Kurtosis | 2.596 | 5.330 | 3.041 | 1.314 | 28.412 | 29.230 | 1.464 | 1.498 | 39.856 | 1.670 | 3.497 |

| Variables | Level | First Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | Constant + Trend | Constant | Constant + Trend | |

| MRR | −0.614 (0.856) | −1.431 (0.837) | −5.496 (0.000) | −5.543 (0.000) |

| WA | 2.034 (0.999) | 0.075 (0.996) | −5.495 (0.000) | −6.147 (0.000) |

| AL | 0.299 (0.916) | −1.663 (0.750) | −4.468 (0.000) | −0.458 (0.004) |

| WGF | −1.016 (0.739) | −1.919 (0.627) | −6.705 (0.000) | −6.653 (0.000) |

| BM | −6.084 (0.000) | −6.146 (0.000) | −1.239 (0.645) | −1.368 (0.852) |

| WAF | −5.712 (0.000) | −6.428 (0.000) | −1.434 (0.553) | −1.547 (0.792) |

| CO2 | 1.205 (0.664) | −1.509 (0.814) | −7.025 (0.000) | −7.021 (0.000) |

| WPEP | −1.150 (0.687) | −1.429 (0.838) | −7.303 (0.000) | −7.332 (0.000) |

| WHA | −6.148 (0.000) | −6.097 (0.000) | −11.689 (0.000) | −11.550 (0.000) |

| GDPPC | −1.380 (0.583) | −0.745 (0.962) | −3.193 (0.027) | −3.344 (0.072) |

| WEA | 0.623 (0.988) | 1.732 (1.000) | −2.227 (0.199) | −5.211 (0.000) |

| Models | Models | ARDL Lag Length | Wald F-Statistics | Diagnostic Tests | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JB Normality Test | Heteroskedasticity | LM Serial Correlation | Ramsey RESET | ||||

| Model-I | MRR/WA, AL, WGF, BM, WAF, CO2, WPEP, CPI, GDPPC, WEA | 2,2,2,2,2,2,2,2,2,2,2 | 3.949 ** | 1.253 (0.534) | 0.990 (0.543) | 1.292 (0.296) | 1.158 (0.276) |

| Model-II | WA/MRR, AL, WGF, BM, WAF, CO2, WPEP, CPI, GDPPC, WEA | 2,2,2,0,0,0,0,0,0,2,2 | 2.767 | 10.019 (0.000) | 1.131 (0.387) | 7.368 (0.004) | 2.139 (0.044) |

| Model-III | AL/WA, MRR, WGF, BM, WAF, CO2, WPEP, CPI, GDPPC, WEA | 1,0,0,2,1,1,2,2,2,0,0 | 3.088 *** | 9.031 (0.010) | 0.721 (0.776) | 4.890 (0.028) | 2.412 (0.031) |

| Model-IV | WGF/WA, AL, MRR, BM, WAF, CO2, WPEP, CPI, GDPPC, WEA | 1,2,2,1,1,0,2,2,1,2,2 | 6.012 * | 0.131 (0.936) | 0.640 (0.847) | 1.106 (0.359) | 1.498 (0.156) |

| Model-V | BM/WA, AL, WGF, MRR, WAF, CO2, WPEP, CPI, GDPPC, WEA | 2,2,0,2,02,2,2,0,2,2 | 1.661 | 0.559 (0.755) | 1.211 (0.356) | 9.692 (0.002) | 1.839 (0.087) |

| Model-VI | WAF/WA, AL, WGF, BM, MRR, CO2, WPEP, CPI, GDPPC, WEA | 2,2,2,0,2,0,2,2,0,2,2 | 1.668 | 0.555 (0.757) | 1.221 (0.349) | 9.724 (0.002) | 2.522 (0.024) |

| Model-VII | CO2/WA, AL, WGF, BM, WAF, MRR, WPEP, CPI, GDPPC, WEA | 2,2,1,1,2,1,2,2,1,1,1 | 5.055 * | 3.148 (0.207) | 0.343 (0.992) | 1.122 (0.355) | 5.295 (0.000) |

| Model-VIII | WPEP/WA, AL, WGF, BM, WAF, CO2, MRR, CPI, GDPPC, WEA | 2,2,1,2,1,2,1,2,1,1,1 | 3.010 | 1.079 (0.582) | 0.430 (0.927) | 0.574 (0.576) | 8.182 (0.000) |

| Model-IX | CPI/WA, AL, WGF, BM, WAF, CO2, WPEP, MRR, GDPPC, WEA | 2,1,2,2,1,2,2,1,2,0,1 | 12.561 * | 0.893 (0.639) | 0.821 (0.681) | 3.582 (0.057) | 16.579 (0.000) |

| Model-X | GDPPC/WA, AL, WGF, BM, WAF, CO2, WPEP, CPI, GMRR, WEA | 1,0,2,2,1,1,2,0,2,2,2 | 2.558 | 2.614 (0.270) | 1.574 (0.173) | 7.007 (0.005) | 0.369 (0.717) |

| Model-XI | WEA/WA, AL, WGF, BM, WAF, CO2, WPEP, CPI, GDPPC, MRR | 2,2,0,0,0,0,0,0,2,2,2 | 3.467 ** | 0.626 (0.730) | 1.578 (0.151) | 7.001 (0.005) | 3.099 (0.005) |

| Narayan Critical Values | Level of Significance | Lower Bounds I(0) | Upper Bounds I(1) | Note: *, **, and *** shows 1%, 5%, and 10% level of significance. | |||

| 10% | 2.07 | 3.16 | |||||

| 5% | 2.33 | 3.46 | |||||

| 1% | 2.84 | 4.10 | |||||

| Variables | ARDL-I | ARDL-II | ARDL-III |

|---|---|---|---|

| ∆ln(WA)t | 0.125 | −7.163 * | 1.580 |

| ∆ln(WA)t−1 | −1.153 | ----- | −7.478 * |

| ∆ln(WA)t−2 | −2.051 | ----- | ----- |

| ∆ln(AL)t | 13.181 | ----- | 18.564 |

| ∆ln(AL)t−1 | 23.435 | ----- | ----- |

| ∆ln(WGF)t | ----- | −3.860 *** | −7.560 ** |

| ∆ln(BM)t | −0.206 | ----- | −2.570 ** |

| ∆ln(BM)t−1 | −0.008 | ----- | ----- |

| ∆ln(BM)t−2 | 0.338 ** | ----- | ----- |

| ∆ln(WAF)t | ----- | −0.116 | 2.522 ** |

| ∆ln(WAF)t−1 | ----- | −0.090 | ----- |

| ∆ln(WAF)t−2 | ----- | 0.420 * | ----- |

| ∆ln(CO2)t | 1.627 * | ----- | −0.375 |

| ∆ln(CO2)t−1 | −0.882 *** | ----- | ----- |

| ∆ln(WPEP)t | ----- | 0.722 *** | 454.173 a,** |

| ∆ln(WPEP)t−1 | ----- | −0.357 | ----- |

| ∆ln(WPEP)t−2 | ----- | −0.657 | ----- |

| ∆ln(CPI)t | 0.155 * | ----- | ----- |

| ∆ln(GDPPC)t | 8.694 * | ----- | 6.336 ** |

| ∆ln(GDPPC)t−1 | ----- | ----- | −8.722 * |

| ∆ln(WEA)t | ----- | 8.011 * | −0.000016 |

| ∆ln(WEA)t−1 | ----- | −1.383 | 0.00034 * |

| ECTt−1 | −1.106 * | −0.460 * | −1.086 * |

| Long-run Elasticity Estimates | |||

| ln(WA) | 3.268 * | 5.979 | 9.354 * |

| ln(AL) | −16.772 *** | ----- | −4.940 |

| ln(WGF) | ----- | −8.383 *** | −6.959 ** |

| ln(BM) | −0.771 ** | ----- | −2.365 ** |

| ln(WAF) | ----- | −1.190 | 2.167 *** |

| ln(CO2) | 2.267 * | ----- | 0.462 |

| ln(WPEP) | ----- | 3.849 ** | 418.055 a,** |

| ln(CPI) | 0.140 ** | ----- | ----- |

| ln(GDPPC) | 2.394 * | ----- | 9.733 * |

| ln(WEA) | ----- | 0.514 | −0.0004 * |

| Constant | 243.235 | ----- | 84.348 |

| Diagnostic Tests | |||

| Wald F-statistics | 3.654 *** | 4.001 *** | 4.359 * |

| JB Test | 0.513 | 0.310 | 0.656 b |

| LM Test | 0.667 | 0.170 | 0.649 b |

| Heteroskedasticity Test | 1.196 | 0.359 | 0.628 b |

| Ramsey RESET Test | 0.570 | 1.930 *** | 1.336 b |

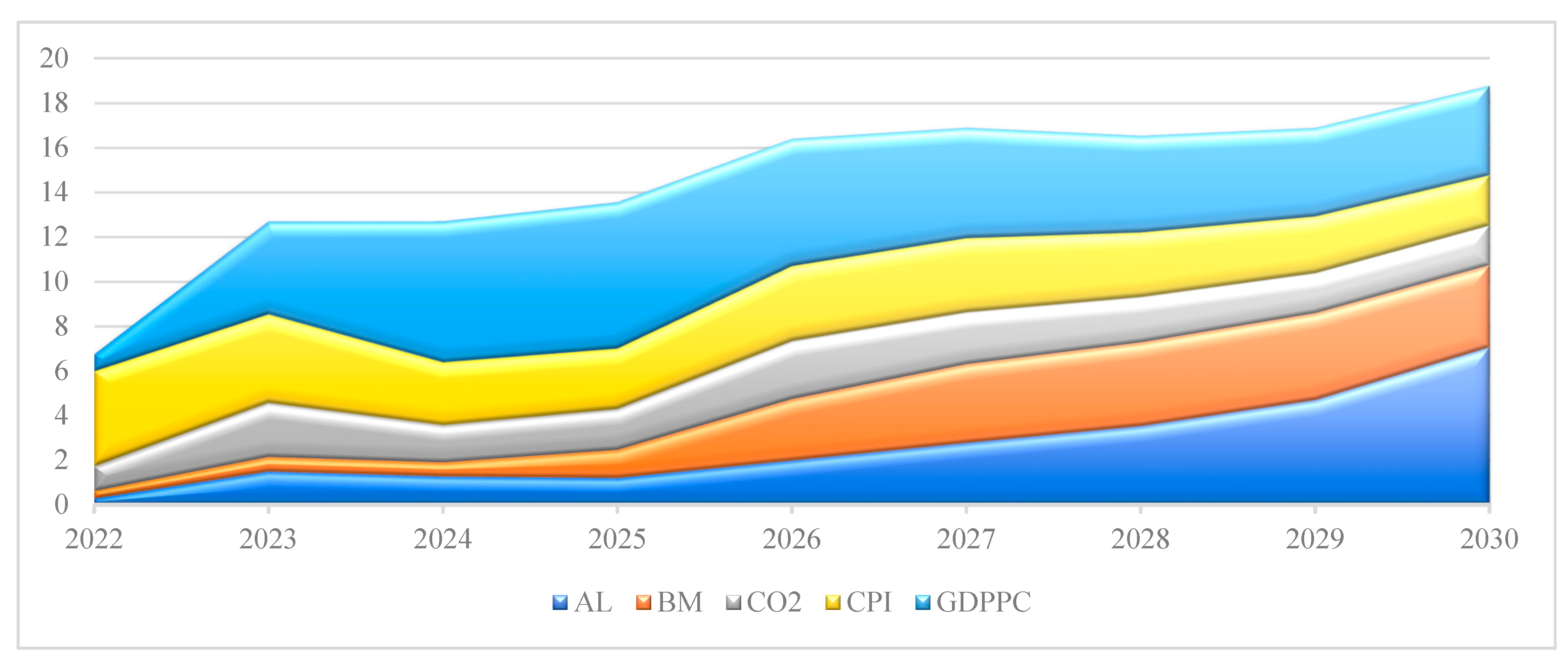

| Period | S.E. | MRR | WA | AL | WGF | BM | WAF | CO2 | WPEP | CPI | GDPPC | WEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2.283 | 74.559 | 4.152 | 0.280 | 1.996 | 0.339 | 2.769 | 1.017 | 2.430 | 4.215 | 0.754 | 7.4843 |

| 2022 | 2.616 | 56.948 | 4.042 | 1.494 | 1.610 | 0.655 | 8.045 | 2.418 | 3.313 | 3.967 | 4.152 | 13.352 |

| 2023 | 3.173 | 40.098 | 5.131 | 1.277 | 1.299 | 0.628 | 19.617 | 1.669 | 2.782 | 2.808 | 6.311 | 18.374 |

| 2024 | 3.497 | 33.070 | 6.601 | 1.199 | 1.459 | 1.264 | 21.301 | 1.830 | 2.747 | 2.704 | 6.555 | 21.265 |

| 2025 | 3.819 | 28.771 | 6.416 | 1.989 | 1.465 | 2.751 | 19.277 | 2.593 | 2.457 | 3.358 | 5.696 | 25.222 |

| 2026 | 4.101 | 26.031 | 5.768 | 2.780 | 1.957 | 3.526 | 17.568 | 2.319 | 2.224 | 3.315 | 4.941 | 29.565 |

| 2027 | 4.411 | 23.091 | 5.078 | 3.523 | 2.306 | 3.752 | 16.765 | 2.032 | 1.922 | 2.890 | 4.320 | 34.315 |

| 2028 | 4.716 | 20.575 | 4.449 | 4.690 | 2.651 | 3.892 | 16.785 | 1.797 | 1.742 | 2.536 | 3.962 | 36.915 |

| 2029 | 5.017 | 19.076 | 4.057 | 7.058 | 2.467 | 3.671 | 15.861 | 1.781 | 1.703 | 2.247 | 4.006 | 38.066 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Anser, M.K.; Zaman, K. Ecofeminism and Natural Resource Management: Justice Delayed, Justice Denied. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7319. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137319

Liu Y, Anser MK, Zaman K. Ecofeminism and Natural Resource Management: Justice Delayed, Justice Denied. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7319. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137319

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yang, Muhammad Khalid Anser, and Khalid Zaman. 2021. "Ecofeminism and Natural Resource Management: Justice Delayed, Justice Denied" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7319. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137319

APA StyleLiu, Y., Anser, M. K., & Zaman, K. (2021). Ecofeminism and Natural Resource Management: Justice Delayed, Justice Denied. Sustainability, 13(13), 7319. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137319