Social Media as a Catalyst for the Enhancement of Destination Image: Evidence from a Mediterranean Destination with Political Conflict

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Destinations with Political Conflict

2.2. Destination Image

2.3. Social Media and Tourism

2.4. Case of North Cyprus

- What is the extent of tourism sector operators’ commitment to utilize social media platforms toward this aim?

- Moreover, are tourism operators aware of the practical value and power of social media platforms to disseminate a true image of the destination that is entangled in political uncertainty?

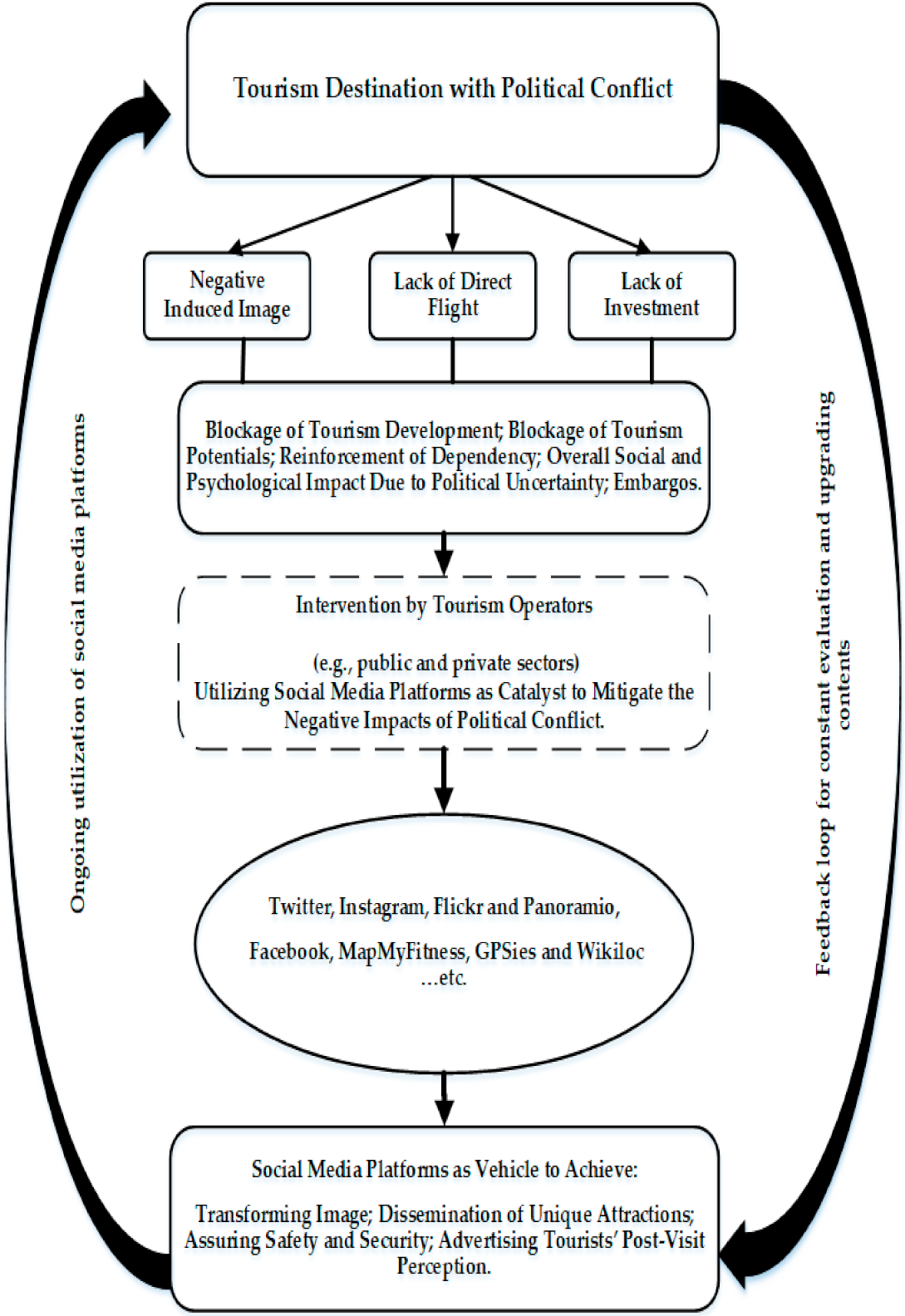

3. Conceptualization

4. Study Method

5. Research Design

6. Data Collection

7. Data Analysis

8. Findings and Discussions

9. Extraction of the Themes and Subthemes

10. Managerial and Theoretical Implications

11. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ritchie, B.W.; Jiang, Y. A review of research on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiralay, S. Political uncertainty and the us tourism index returns. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, M.R.; Chatterjee, D. Vulnerability and resilience of the tourism sector in India: Effects of natural disasters and internal conflict. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W. Chaos, crises and disasters: A strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lojo, A.; Li, M.; Xu, H. Online tourism destination image: Components, information sources, and incongruence. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Richardson, S.L. Motion picture impacts on destination images. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 216–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, I.; Museros, L.; González-Abril, L. Exploring the Cognitive-Affective-Conative Image of a Rural Tourism Destination Using Social Data. In Proceedings of the JARCA Workshop on Qualitative Systems and Applications in Diagnosis, Robotics and Ambient Intelligence, Almería, Spain, 23–29 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfeld, Y.; Korman, T. Between war and peace: Conflict heritage tourism along three Israeli border areas. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 437–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Dong, L. Image Monitoring and Management of Hot Tourism Destination Based on Data Mining Technology in Big Data Environment. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2021, 80, 103515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghizlane, A.; Souaf, M.; Elwazani, Y. Territorial Marketing Toolbox, an operational tool for territorial mix formalization. World Sci. News 2017, 65, 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Farmaki, A.; Altinay, L.; Botterill, D.; Hilke, S. Politics and sustainable tourism: The case of Cyprus. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasarata, M.; Altinay, L.; Burns, P.; Okumus, F. Politics and sustainable tourism development—Can they co-exist? Voices from North Cyprus. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinay, L.; Bowen, D. Politics and tourism interface. The Case of Cyprus. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 939–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, H.; Kilic, H. An institutional appraisal of tourism development and planning: The case of the Turkish Republic of North Cyprus (TRNC). Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Gerritsen, R. What do we know about social media in tourism? A review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 10, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perles-Ribes, J.F.; Ramón-Rodríguez, A.B.; Such-Devesa, M.J.; Moreno-Izquierdo, L. Effects of political instability in consolidated destinations: The case of Catalonia (Spain). Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, R.; El-Kassrawy, Y.A.; Agag, G. Integrating Destination Attributes, Political (In)Stability, Destination Image, Tourist Satisfaction, and Intention to Recommend: A Study of UAE. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 43, 839–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.D.; Campo, S. The influence of political conflicts on country image and intention tovisit: A study of Israel’s image. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, E.; Isaac, R.K. What destination marketers can learn from their visitors’ blogs: An image analysis of Bethlehem, Palestine. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2012, 1, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massi, M.; De Nisco, A. Chapter 8 The Internet-Based Marketing of Ecotourism: Are Ecotourists Really Getting What They Want? In Tourism Planning and Destination Marketing; Camilleri, M.A., Ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 161–182. ISBN 978-1-78756-292-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Chan, H.; Pan, S. The Impacts of Mass Media on Organic Destination Image: A Case Study of Singapore. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 860–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. Understanding online community user participation: A social influence perspective. Internet Res. 2011, 21, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, S. Measuring and improving the image of a post-conflict nation: The impact of destination branding. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canazza, M.R. The Internet as a global public good and the role of governments and multilateral organizations in global internet governance. Meridiano 47 J. Glob. Stud. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Chen, J.S. Destination image formation process: A holistic model. J. Vacat. Mark. 2016, 22, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, R.M.; Cai, L. Social media sites in destination image formation. Tour. Soc. Sci. Ser. 2013, 18, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škare, M.; Soriano, D.R.; Porada-Rochoń, M. Impact of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegar, R.; Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Ruhanen, L. COVID-19 and a justice framework to guide tourism recovery. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 103161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirman, D. Marketing of tourism destinations during a prolonged crisis: Israel and the Middle East. J. Vacat. Mark. 2002, 8, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, H.; Tabari, S.; Watthanakhomprathip, W. The impact of political instability on tourism: Case of Thailand. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2013, 5, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumayer, E. The Impact of Political Violence on Tourism: Dynamic Cross-national Estimation. J. Conflict Resolut. 2004, 48, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, M.A.; Georgiou, A. The impact of political instability on a fragile tourism product. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Is Northen Cyprus Safe? Available online: https://www.tripadvisor.com/ShowTopic-g190378-i9456-k8565652-Kyrenia_Kyrenia_District.html (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Mehtap-Smadi, S.; Hashemipour, M. In pursuit of an international education destination: Reflections from a university in a small island state. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2011, 15, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanouar, C.; Goaied, M. Tourism, terrorism and political violence in Tunisia: Evidence from Markov-switching models. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, R.K.; Eid, T.A. Tourists’ destination image: An exploratory study of alternative tourism in Palestine. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1499–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Fu, X.; Jin, W.; Okumus, F. Constructing a model of exhibition attachment: Motivation, attachment, and loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. Tourists’ evaluations of destination image, satisfaction, and future behavioral intentions-the case of mauritius. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2009, 26, 836–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophorou, C.; Şahin, S.; Pavlou, S. Media Narratives, Politics and the Cyprus Problem; Peace Research Institute: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2010; ISBN 9788272883231. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, J. North Cyprus: Tourism and the Challenge of Non-recognition. J. Sustain. Tour. 1999, 7, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özersay South Interfering with Tourism to North Cyprus. Available online: https://www.lgcnews.com/south-interfering-with-tourism-to-north-cyprus/ (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Alipour, H.; Fatemi, H.; Malazizi, N. Is edu-tourism a sustainable option? A case study of residents’ perceptions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan Katircioǧlu, S. International tourism, higher education and economic growth: The case of north cyprus. World Econ. 2010, 33, 1955–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicak, H.; Altinay, M.; Jenkins, H. Forecasting the tourism demand of north Cyprus. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2005, 12, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.; Timothy, D.J. Travelling to the “other side”: The occupied zone and Greek Cypriot views of crossing the green line. Tour. Geogr. 2006, 8, 162–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coshall, J.T. The threat of terrorism as an intervention on international travel flows. J. Travel Res. 2003, 42, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO Tourism Highlights: 2018 Edition; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2018; ISBN 9789284419876.

- Amujo, O.C.; Otubanjo, O. Leveraging Rebranding of â€~Unattractiveâ€TM Nation Brands to Stimulate Post-Disaster Tourism. Tour. Stud. 2012, 12, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttavuthisit, K. Branding Thailand: Correcting the negative image of sex tourism. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2007, 3, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinay, L.; Altinay, M.; Bicak, H.A. Political scenarios: The future of the North Cyprus tourism industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2002, 14, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanon, W.; Wang, E. Comparing the impact of political instability and terrorism on inbound tourism demand in Syria before and after the political crisis in 2011. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Saura, I.G.; Garcı́a, H.C. Destination image: Towards a conceptual framework. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, S.C.; Alvarez, M.D. Country versus destination image in a developing country. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 748–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegegne, W.A.; Moyle, B.D.; Becken, S. A qualitative system dynamics approach to understanding destination image. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.K.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, J. Dynamic Nature of Destination Image and Influence of Tourist Overall Satisfaction on Image Modification. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; Vinhas da Silva, R.; Antova, S. Image, satisfaction, destination and product post-visit behaviours: How do they relate in emerging destinations? Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; Henthorne, T.L.; Sahin, S. Destination Image and Brand Personality of Jamaica: A Model of Tourist Behavior. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 1057–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaran, U. Examining the Relationships of Cognitive, Affective, and Conative Destination Image: A Research on Safranbolu, Turkey. Int. Bus. Res. 2016, 9, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghizzawi, M.; Salloum, S.A.; Habes, M. The role of social media in tourism marketing in Jordan. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Lang. Stud. 2018, 2, 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kiráľová, A.; Pavlíčeka, A. Development of Social Media Strategies in Tourism Destination. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 175, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, C.A.; Var, T. Tourism Policy and Planning: Basics, Concepts, Cases, 4th ed.; Routhledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Govers, R.; Go, F.M.; Kumar, K. Virtual destination image a new measurement approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 977–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary, K.W. A model of destination image. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A.; Martin, J.D. Factors influencing destination image. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, A.A.; Carter, L.L. The affective and cognitive components of country image in Kuwait. Int. Mark. Rev. 2011, 28, 559–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine-Roig, E.; Huertas, A. How safety affects destination image projected through online travel reviews. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, G.G.; Sengün, G. The Effects of Social Media on Tourism Marketing: A Study among University Students. Manag. Adm. Sci. Rev. 2015, 4, 772–786. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.W.; Stewart, K.; Larsen, D. Toward an Agenda of High-Priority Tourism Research. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C.; Walden-Schreiner, C.; Barros, A.; Rossi, S.D. Using social media images and text to examine how tourists view and value the highest mountain in Australia. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles da Mota, V.; Pickering, C. How can we use social media to know more about visitors to natural areas. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Monitoring and Management of Visitors in Recreational and Protected Areas (MMV9), Bordeaux, France, 29–31 August 2018; pp. 72–74. [Google Scholar]

- Toivonen, T.; Heikinheimo, V.; Fink, C.; Hausmann, A.; Hiippala, T.; Järv, O.; Tenkanen, H.; Di Minin, E. Social media data for conservation science: A methodological overview. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 233, 298–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagni, F.; Amorim Maia, A.T.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Langemeyer, J. Digital co-construction of relational values: Understanding the role of social media for sustainability. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1309–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghermandi, A.; Sinclair, M. Passive crowdsourcing of social media in environmental research: A systematic map. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 55, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilo, S.; Collins-Kreiner, N. Tourism, heritage and politics: Conflicts at the City of David, Jerusalem. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härting, R.; Kaim, R.; Fleischer, L.; Sprengel, A. Potentials of Digital Business Models in Tourism—Qualitative Study with German Experts. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Congress on Information and Communication Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Achrol, R.S.; Kotler, P. Frontiers of the marketing paradigm in the third millennium. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, R.; Conduit, J.; Fahy, J.; Goodman, S. Social media engagement behaviour: A uses and gratifications perspective. J. Strateg. Mark. 2016, 24, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Mehraliyev, F.; Liu, C.; Schuckert, M. The roles of social media in tourists’ choices of travel components. Tour. Stud. 2020, 20, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Zhong, D. Using social network analysis to explain communication characteristics of travel-related electronic word-of-mouth on social networking sites. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, M.; Scott, N. Influence of Social Media on Chinese Students’ Choice of an Overseas Study Destination: An Information Adoption Model Perspective. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.E.; Lee, K.Y.; Shin, S.I.; Yang, S.B. Effects of tourism information quality in social media on destination image formation: The case of Sina Weibo. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Over 70+ Online Travel Booking Statistics. Available online: https://www.condorferries.co.uk/online-travel-booking-statistics (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Global Social Media Stats—DataReportal—Global Digital Insights. Available online: https://datareportal.com/social-media-users (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Leung, D.; Law, R.; van Hoof, H.; Buhalis, D. Social Media in Tourism and Hospitality: A Literature Review. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TripAdvisor Network Effect and the Benefits of Total Engagement. Available online: https://www.tripadvisor.com/TripAdvisorInsights/w828 (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Filieri, R.; McLeay, F. E-WOM and Accommodation: An Analysis of the Factors That Influence Travelers’ Adoption of Information from Online Reviews. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, S.; Larke, R.; Kilgour, M. Applications of social media for medical tourism marketing: An empirical analysis. Anatolia 2018, 29, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.; Koenig-Lewis, N. An experiential, social network-based approach to direct marketing. Direct Mark. An Int. J. 2009, 3, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narangajavana, Y.; Callarisa Fiol, L.J.; Moliner Tena, M.Á.; Rodríguez Artola, R.M.; Sánchez García, J. The influence of social media in creating expectations. An empirical study for a tourist destination. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 65, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoğlu, B.B.; Taheri, B.; Okumus, F.; Gannon, M. Understanding the importance that consumers attach to social media sharing (ISMS): Scale development and validation. Tour. Manag. 2020, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, S. New paradigm of digital marketing in emerging markets: From social media to social customer relationship management. Int. J. Manag. Pract. 2016, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.S.; Khalafinezhad, R.; Ismail, W.K.W.; Rasid, S.Z.A. Impact of CRM Factors on Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.C.; Chuang, L.M.; Huang, C.M. A Study of the Impact of the e-CRM Perspective on Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty-Exemplified by Bank Sinopac. J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 2012, 4, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, D.K.; Reichheld, F.; Dawson, C. Winning customer loyalty is the key to a winning CRM strategy. Ivey Bus. J. 2003, 67, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ballings, M.; Van den Poel, D. CRM in social media: Predicting increases in Facebook usage frequency. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 244, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M.A.R. The Cyprus Issue: Reflection on TRNC. Arts Fac. J. 2012, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacher, H.; Kaymak, E. Transforming identities: Beyond the politics of non-settlement in North Cyprus. Mediterr. Polit. 2005, 10, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, C. An assessment of the partition of Cyprus. Int. Stud. Perspect. 2007, 8, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North Cyprus Offices of the Representatives Abroad. Available online: https://www.turkishcyprus.com/representative-offices.html (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Connolly, J.; Gifford, A.; Kanol, D.; Yilmaz, O. The role of transnational education in public administration and public affairs to support ‘good governance’ in the Turkish republic of North Cyprus. Teach. Public Adm. 2018, 36, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eralp, D.U.; Beriker, N. Assessing the conflict resolution potential of the EU: The Cyprus conflict and accession negotiations. Secur. Dialogue 2005, 36, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, T. The European Union and the Cyprus conflict: Modern Conflict, Postmodern Union, 1st ed.; Manchester University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hate Speech in Public Discourse Cyprus. Available online: https://kisa.org.cy/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/WAS_Cyprus-report_final.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Lockhart, D. Tourism in Northern Cyprus: Patterns, policies and prospects. Tour. Manag. 1994, 15, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmqvist, J.; Visconti, L.M.; Grönroos, C.; Guais, B.; Kessous, A. Understanding the value process: Value creation in a luxury service context. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunja, S.R.; GVRK, A. Examining the effect of eWOM on the customer purchase intention through value co-creation (VCC) in social networking sites (SNSs). Manag. Res. Rev. 2018, 43, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, T.; Garry, T. Co-creation and ambiguous ownership within virtual communities: The case of the Machinima community. J. Consum. Behav. 2014, 13, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.C.; Wu, L.H. Service engineering: An interdisciplinary framework. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2010, 51, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte Alonso, A.; Bressan, A.; O’Shea, M.; Krajsic, V. Website and Social Media Usage: Implications for the Further Development of Wine Tourism, Hospitality, and the Wine Sector. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2013, 10, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCreary, A.; Seekamp, E.; Davenport, M.; Smith, J.W. Exploring qualitative applications of social media data for place-based assessments in destination planning. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Tourism and Environment. Tourism Statistics. Available online: http://turizmplanlama.gov.ct.tr/TURİZM-İSTATİSTİKLERİ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Kelman, H.C. Compliance, identification, and internalization three processes of attitude change. J. Conflict Resolut. 1958, 2, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Min, Q.; Han, S. Understanding users’ continuous content contribution behaviours on microblogs: An integrated perspective of uses and gratification theory and social influence theory. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 39, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y. Understanding social influence theory and personal goals in e-learning. Inf. Dev. 2016, 32, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, X.; Sun, J.; Zhou, G. Exploring physicians’ extended use of electronic health records (EHRs): A social influence perspective. Health Inf. Manag. J. 2016, 45, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, P. Twitter’s diffusion in sports journalism: Role models, laggards and followers of the social media innovation. New Media Soc. 2016, 18, 484–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, C.A.; Taylor, G.D. Book Review: Vacationscape: Designing Tourist Regions. J. Travel Res. 1973, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwan, M.H. Advancing Tourist Destination Image Theory: Formation Antecedents and Behavioral Consequences. Ph.D. Thesis, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich, J.N. Book Reviews: Vacationscape: Designing Tourist Regions by Clare A. Gunn (Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, 115 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10003, Second Edition, 1988, 208 pages. J. Travel Res. 1988, 27, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalu, F.A.; Bwalya, J.C. What makes qualitative research good research? An exploratory analysis of critical elements. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2017, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G. Pros and cons of different sampling techniques. Int. J. Appl. Res. 2017, 3, 749–752. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Transaction: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J. Grounded theory. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 301–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.N. Qualitative Research Method: Grounded Theory. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 9, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, T. Grounded theory. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 29, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- van Teijlingen, E.R.; Rennie, A.-M.; Hundley, V.; Graham, W. The importance of conducting and reporting pilot studies: The example of the Scottish Births Survey. J. Adv. Nurs. 2001, 34, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.W. Qualitative interview design: A practical guide for novice investigators. Qual. Rep. 2010, 15, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, C. General Guidelines for Conducting Interviews. Available online: http://managementhelp.org/evaluatn/intrview.htm (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- Mack, N.; Woodsong, C.; MacQueen, K.; Guest, G.; Namey, E. Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector’s Field Guide; FHI360: Durham, NC, USA, 2005; ISBN 0939704986. [Google Scholar]

- Atlas. Ti Qualitative Data Analysis. 2021. Available online: https://atlasti.com/2021/03/09/35383/ (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Baralt, M. Tips & Tools #18: Coding Qualitative Data. Available online: https://www.ocic.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Coding-Center-for-Evaluation-and-Research.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Gramenz, G. How to Code a Document and Create Themes. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sHv3RzKWNcQ&ab_channel=GaryGramenz (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Fischer, C.T. Bracketing in qualitative research: Conceptual and practical matters. Psychother. Res. 2009, 19, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, H.; Smith, J. Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evid. Based. Nurs. 2015, 18, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabuza, L.H.; Govender, I.; Ogunbanjo, G.A.; Mash, B. African primary care research: Qualitative data analysis and writing results. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2014, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golafshani, N. Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 2003, 8, 597–607. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rabiee, F. Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2004, 63, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stocks, R. eMarketing: The Essential Guide to Marketing in a Digital World, 5th ed.; Quirk eMarketing (Pty) Ltd.: Cape Town, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barefoot, D.; Szabo, J. Friends with Benefits: A Social Media Marketing Handbook, 2nd ed.; No Starch Press: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chester, J.; Montgomery, K.C. The role of digital marketing in political campaigns. Internet Policy Rev. 2017, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.R.; Galvão, A.; Martins, A.M.T. Route of the World Heritage Monasteries in Portugal and a Digital Touristic Platform. Int. J. Herit. Digit. Era 2012, 1, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jensen, M.J. Social Media and Political Campaigning. Int. J. Press. 2017, 22, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaalian, F.; Halpenny, E. Exploring destination loyalty: Application of social media analytics in a nature-based tourism setting. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R. Governance and sustainable tourism: What is the role of trust, power and social capital? J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errichiello, L.; Marasco, A. Tourism innovation-oriented public-private partnerships for smart destination development. Bridg. Tour. Theory Pract. 2017, 8, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suherlan, H. Strategic alliances in institutions of higher education: A case study of Bandung and Bali Institutes of Tourism in Indonesia. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2017, 3, 158–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, B.D.; Pehlivan, E. Social spending: Managing the social media mix. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, C.H.; Parasnis, G. From social media to social customer relationship management. Strateg. Leadersh. 2011, 39, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.B.; Crouch, G.I. The Competitive Destination: A Sustainable Tourism Perspective; Cabi: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. Tourism Planning: Policies, Processes and Relationships, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.; Park, S. Thematic analysis of destination images for social media engagement marketing. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; Saunders, B.; Waterfield, J.; Kingstone, T. Can sample size in qualitative research be determined a priori? Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2018, 21, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. Theoretical Saturation. In Keywords in Qualitative Methods; Given, L., Ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2008; pp. 875–876. [Google Scholar]

- The Unresolved Cyprus Problem. Available online: https://www.lepetitjuriste.fr/the-unresolved-cyprus-problem/ (accessed on 19 June 2021).

- Olya, H.; Alipour, H. Modeling tourism climate indices through fuzzy logic. Clim. Res. 2015, 66, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minazzi, R. Social Media Marketing in Tourism and Hospitality; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-05181-9. [Google Scholar]

| ARRIVALS BY MONTH | TOTAL NUMBER OF ARRIVALS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | % Change | |

| JANUARY | 105,630 | 112,232 | 6.3 |

| FEBRUARY | 128,028 | 128,743 | 0.6 |

| MARCH | 131,087 | 44,107 | −66.4 |

| APRIL | 146,768 | 67 | −100.0 |

| MAY | 129,844 | 37 | −100.0 |

| JUNE | 150,051 | 477 | −99.7 |

| JULY | 152,247 | 20,228 | −86.7 |

| AUGUST | 159,250 | 35,119 | −77.9 |

| SEPTEMBER | 192,123 | 11,727 | −93.9 |

| OCTOBER | 177,127 | 13,275 | −92.5 |

| NOVEMBER | 148,408 | 14,552 | −90.2 |

| DECEMBER | 129,416 | 8282 | −93.6 |

| TOTAL | 1,749,979 | 388,846 | −77.8 |

|

| Organization | Interviewees’ Position | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern Mediterranean University | Professor of sustainable tourism | 1 |

| Eastern Mediterranean University | Assistant professor of tourism | 1 |

| North Cyprus Ministry of Tourism | Director of tourism ministry | 1 |

| North Cyprus Ministry of Tourism | Undersecretary of tourism ministry | 1 |

| North Cyprus Ministry of Tourism | Deputy director of promotion and marketing sector of tourism ministry | 1 |

| North Cyprus Ministry of Tourism | Visual communication and social media responsible of tourism ministry | 1 |

| Cyprus Turkish Tourism and Travel Agents’ Union (KITSAB) | Head of KITSAB, former director of marketing and promotion of tourism ministry, owner of a travel agency | 1 |

| Cyprus Turkish Tourism and Travel Agents’ Union (KITSAB) | General secretary of KITSAB, Pars tourism and travel agency director | 1 |

| Limak hotel | Promotion and marketing manager of Limak hotel | 1 |

| Paisan Educational and Immigration Institute | Director of Paisan institute, social media Influencer with 61K followers | 1 |

| Total | 10 |

| Themes/Codes Relevant to Social Media Platforms Utilization | Subthemes | Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness of social media |

|  |

| Social media and tourism |

| |

| Social media and destination image |

| |

| Investment in social media |

| |

| Commitment to utilizing social media |

|  |

| Social media and marketing |

| |

| Social media and networking |

| |

| Social media and regional marketing |

|  |

| Lack of policy on social media |

| |

| Budget deficiency |

| |

| Lack of infrastructure |

| |

| Lack of collaboration |

|

| Themes/Codes Relevant to Political Deadlock Undermining Destination Image and Development | Subthemes | Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of direct flight |

|  |

| Lack of investment |

| |

| Lack of recognition |

| |

| Frequency of governance |

| |

| Lack of partnership |

| |

| Lack of strategy |

| |

| Lack of collaboration with the universities |

| |

| Lack of institutions |

| |

| Distribution of negative image by political adversary. |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Farhangi, S.; Alipour, H. Social Media as a Catalyst for the Enhancement of Destination Image: Evidence from a Mediterranean Destination with Political Conflict. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137276

Farhangi S, Alipour H. Social Media as a Catalyst for the Enhancement of Destination Image: Evidence from a Mediterranean Destination with Political Conflict. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137276

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarhangi, Sanaz, and Habib Alipour. 2021. "Social Media as a Catalyst for the Enhancement of Destination Image: Evidence from a Mediterranean Destination with Political Conflict" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137276

APA StyleFarhangi, S., & Alipour, H. (2021). Social Media as a Catalyst for the Enhancement of Destination Image: Evidence from a Mediterranean Destination with Political Conflict. Sustainability, 13(13), 7276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137276