Socio-Environmental Impacts of the Avocado Boom in the Meseta Purépecha, Michoacán, Mexico

Abstract

:1. Introduction

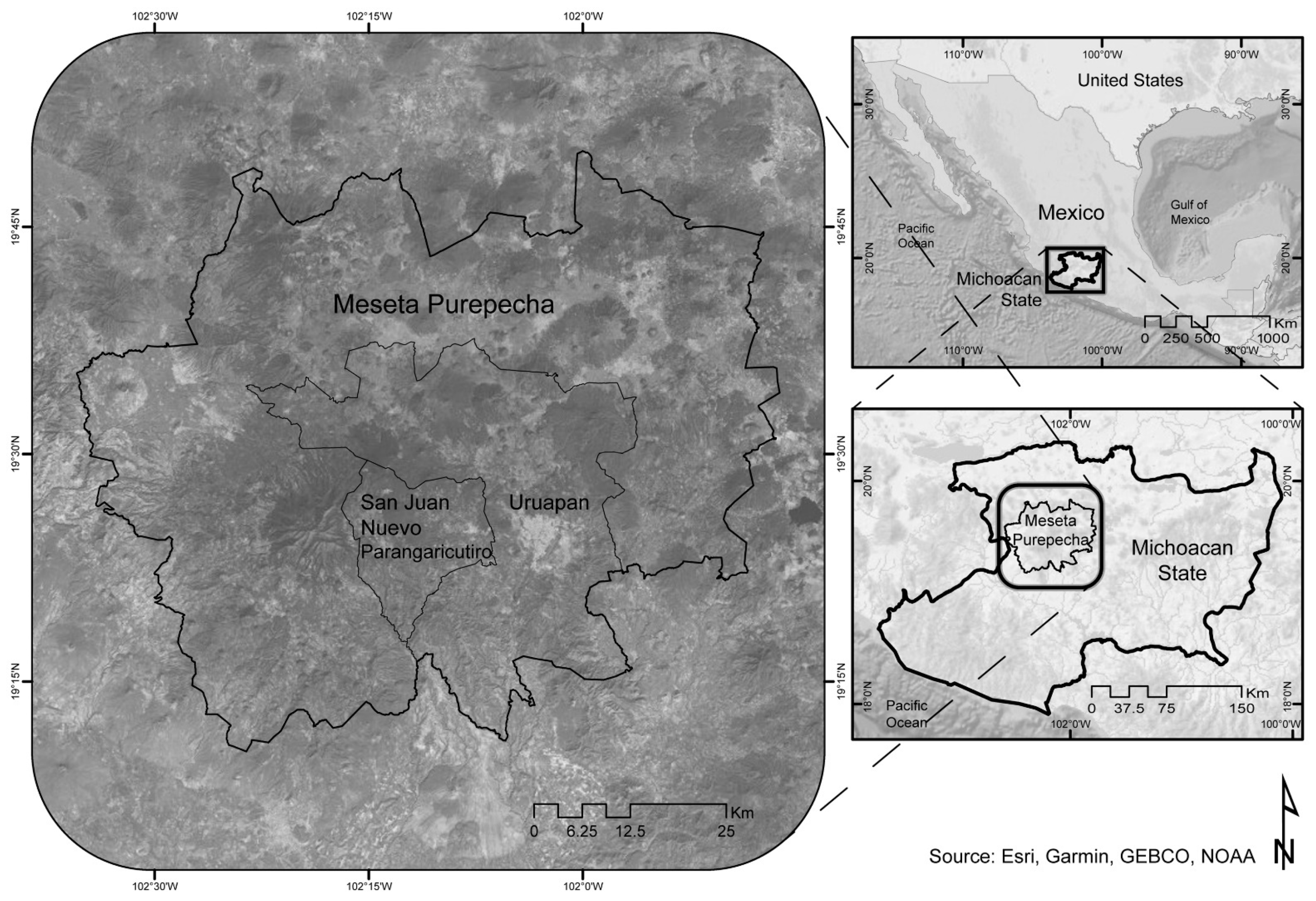

2. The Region, Methods, and Sources

2.1. The Meseta Purépecha

2.2. Methods

- Between November 2016 and March 2018, 33 in-depth semi-structured interviews [24] were carried out in the towns of Arandín, Milpillas, and San Juan Nuevo in San Juan’s municipality, and in the town of Capácuaro, and Uruapan City in the municipality of Uruapan. The interviews were based on a semi-structured questionnaire (included in Appendix A), which was elaborated based on the methodology proposed by Kallio et al. (2016) [24] and applied to key informants, who were based on the previous knowledge of the region and on the “snow ball” sampling technique. This is specifically used for individual interviews and is a type of deterministic sampling method. In this technique the first interviews are applied to a group of key informants previously identified (these were originally eight people in our case study) asking them to recommend other potential interviewees who from their perspective are also relevant actors in the process under study, and so on, aiming to reach a relevant number of interviews until the responses become consistently repetitive [25,26]. We choose this sampling method as it allowed us to reach key informants between populations difficult to access [27], due to the prevailing mistrust among avocado producers, government officers, and community authorities due to the generalized violence, extorsions, and kidnappings in the region committed by the organized crime.The “types” of actors that we interviewed were:Twelve small- and medium-scale farmers who own and/or rent private land where they grow avocado; eight sanitary technicians, in charge of the registration and authorization of avocado cutting and shipping of export permits to the US; two municipal (government) authorities of both San Juan Nuevo and Uruapan; the president of the indigenous community of San Juan Nuevo, five agricultural workers, and four regional experts in the themes of: forestry, water, and land-use change.The number of the different actors interviewed and the size of the whole sample were defined based on the repetitiveness of the information gathered in the different interviewees [27]. These interviews provided qualitative information, critical for the understanding of the process under analysis, based on the perspectives of different stakeholders and relevant actors.

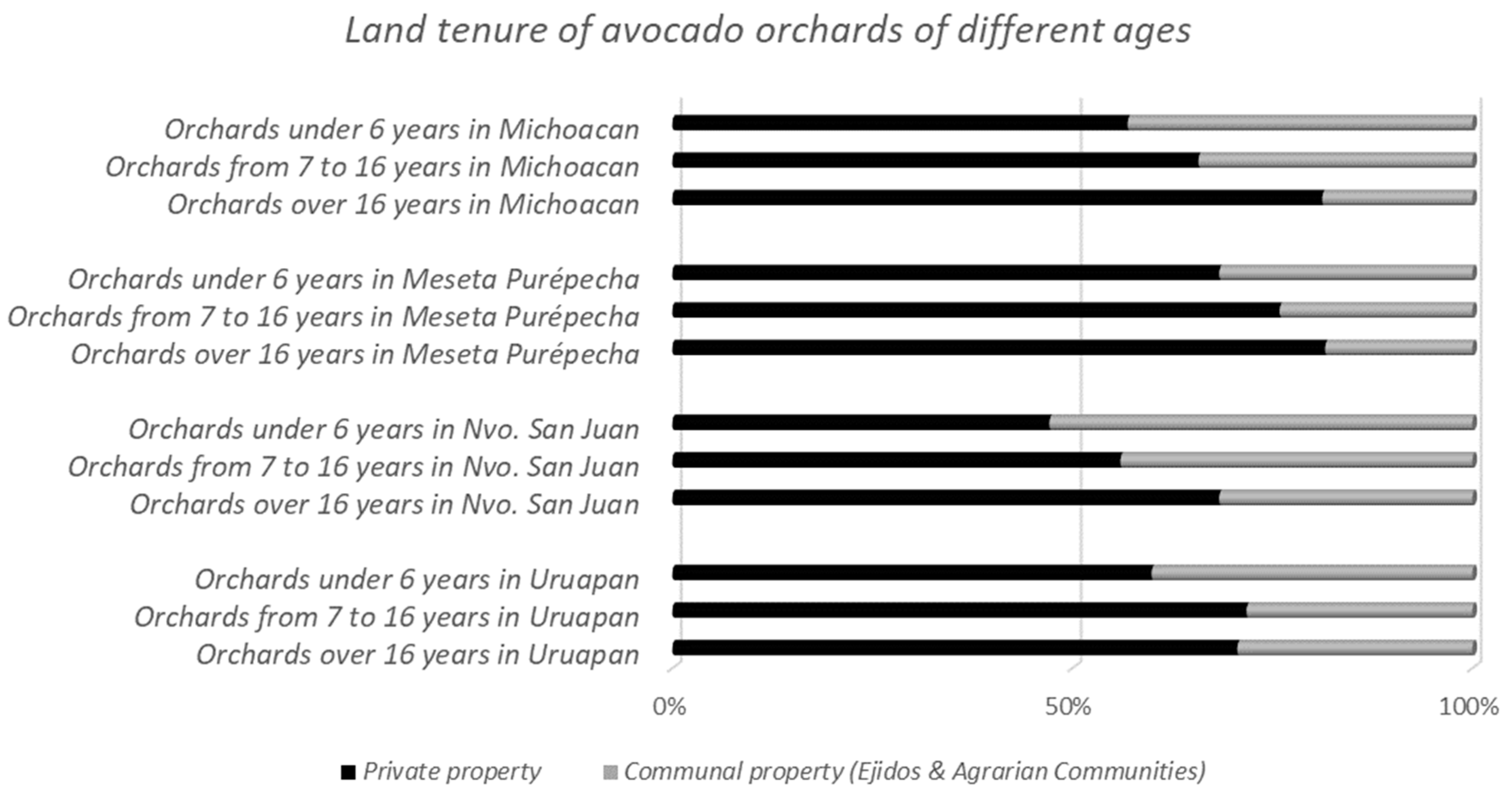

- For the analysis and grouping of the ages of the orchards and land tenure, we conducted an overlay analysis with the software ArcMap ver. 10.3 using the data of the Study of Assessment of Ecological Impacts of Avocado Cultivation, at the Regional and Plot Level, for the years 1995, 2005, and 2011 by Burgos et al., 2011a, 2012 [7,8] and the data on land tenure provided by the Registro Agrario Nacional [28].

- This work is also based on the analysis of different documental sources: the 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2020 Population and the Agricultural Censuses of the National Institute of Statistics, Geography, and Information Technology (INEGI) [14,15,23]; the Human Development Index drafted by the United Nations Development Program [29], the National System of Information on Market Integration of the Ministry of Economics of Mexico [30]; the statistical database of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAOSTAT) [8], and the Agri-Food and Fisheries Information Service of the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fishing, and Food of the United States of America [31]. This diverse information enabled a comprehensive characterization of the social and economic context of the process under study.

3. Results

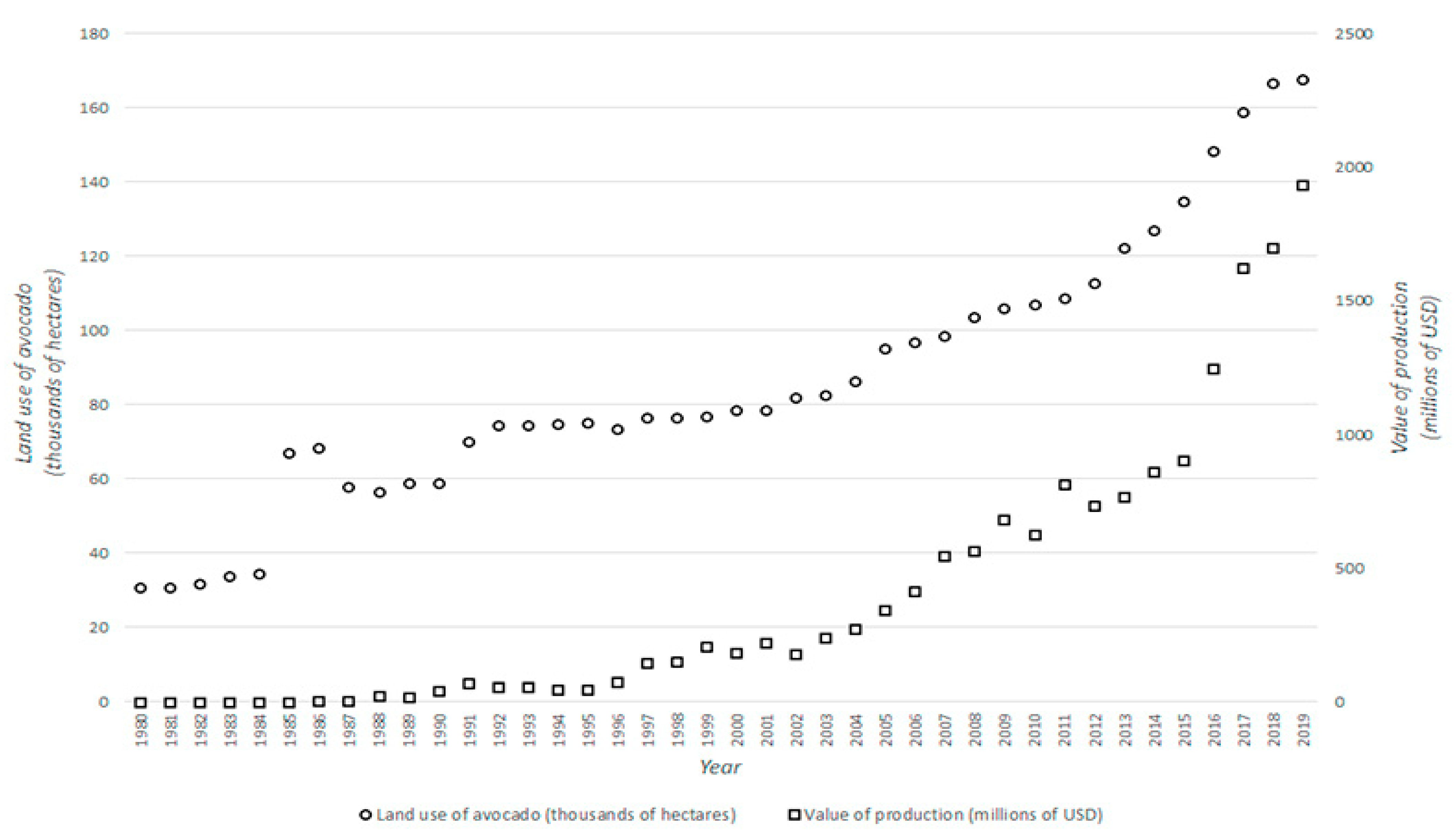

3.1. The Expansion of Avocado in Michoacán

3.2. Impacts of Public Policies on Avocado Expansion

3.3. Main Social Impacts: Concentration of Lands, Productive Capacities, and Profits

3.4. Main Environmental Impacts: Land-Use Change, Water and Soil Pollution, and Forest Fragmentation

3.5. Vulnerability of the Avocado Production System

3.6. An Alternative Model: The Community of San Juan Nuevo Parangaricutiro

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- I.

- Production1. How long have you been growing avocado?2. What did you do before producing avocado?3. How did you start growing avocado?4. What is the area that has been sown?5. Do you produce any other produce in the orchard?6. What is the yield of your orchard?7. How many times do you harvest in a year?8. Has yield changed in recent years?9. What variety of avocado do you produce?10. Where did you get the seedlings to plant the orchard?11. How do you manage the orchard?ConventionalOrganic (to question 16)12. Secondary vegetation removal13. Use of HerbicideWhich?14. FertilizerWhich?15. None16. What is the origin of your organic inputs?17. Which ones do you use?

- Bordeaux broth

- Sulfo-calcium

- Bocachi

- Lombri-compost

- Humus

- Others

18. Does your orchard have irrigation? No (to question 22)19. How much water do you use to irrigate?20. Where does the water you use to irrigate come from?21. Is water available throughout the year?22. Do you require electricity for your production process?23. Do you know roughly the cost of producing one ha per year?Water consumption:Fertilizer consumption:Phytosanitary control (herbicides/organic inputs):Machinery and equipment:Other:24. Do you have any certification?Good practicesOrganicExport25. What are the advantages of these schemes?26. What are the disadvantages of these schemes? - II.

- Commercialization27. Who do you sell it to?28. How do you sell it?29. Do you know if it is exported?Where?30. Have you always sold it to the same people?31. It belongs to an organization of producers/marketers (No to 35)32. How long have you been with the organization?33. What are the advantages of belonging to the organization?34. In your experience, what is the reason for the avocado boom?

- III.

- Property regime35. Is the orchard yours, is it part of an ejido, is it private property, is the rent?36. Does your orchard belong/belonged to any ejido or community?37. Do you know what used to be produced on the land where you have your avocado orchard? (No to question 39)38. When was the substitution made?39. Why was the crop substituted?

- IV.

- On challenges and perspectives in avocado cultivation40. What do you consider the main risks in avocado production?

- Overproduction in the region

- Competition with other areas of the country

- Competition with other countries

- Others

41. Problems with unfavorable weather conditions in the region- Hail

- Frost

- Excess rain

- Lack of rain

- Increase in temperature

- Others

42. Problems with conditions associated with consumption- Decrease in national consumption

- Market saturation

- Decrease in market prices

- Others

43. How many people work in the orchard?44. How long did their work in a year?45. How do you consider the access roads to your orchard?46. In general terms, how would you consider the effect that avocado cultivation has had in economic terms in the region?47. In general terms, how would you consider the effect that avocado cultivation has had in social terms in the region?48. What would happen to you if the avocado markets declined or collapsed?49. What do you think would happen to the region if the avocado markets declined or collapsed?50. Do you observe impacts on water or soil contamination in your orchard in recent years?51. Do you observe impacts on water or soil contamination in the region in recent years? - V.

- General information52. Where are you from?53. What is your production unit called?54. Who do you consider to be the key people who started avocado cultivation in the region?55. What is your principal occupation?Date:Place:Name:Age:

References

- SAGARPA. Atlas Agroalimentario 2012–2018, Primera ed.; Secretaría de Agricultura, Recursos Naturales, Pesca y Alimentación, Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y pesquera: Ciudad de México, México, 2018.

- FAO (Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura). FAOSTAT Database; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/es/#home (accessed on 17 September 2019).

- Curtis, P.G.; Slay, C.M.; Harris, N.L.; Tyukavina, A.; Hansen, M.C. Classifying drivers of global forest loss. Science 2018, 361, 1108–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BirdLife International. What Are Key Biodiversity Areas? BirdLife International Data Zone. Available online: http://datazone.birdlife.org/sowb/casestudy/what-are-key-biodiversity-areas (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- Seymour, F.; Harris, N.L. Reducing tropical deforestation. Science 2019, 365, 756–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barsimantov, J.; Antezana, J.N. Forest cover change and land tenure change in Mexico’s avocado region: Is community forestry related to reduced deforestation for high value crops? Appl. Geogr. 2012, 32, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, A.; Anaya, C.; Solorio, I. Impacto Ecológico del Cultivo de Aguacate a Nivel Regional y de Parcela en el Estado de Michoacán: Definición de una Tipología de Productores; Informe Final a la Fundación Produce Michoacán (FPM) y la AAL-PAUM; Centro de Investigaciones en Geografía Ambiental (CIGA/UNAM Campus Morelia): Morelia, Mexico, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Burgos, A.; Anaya, C.; Solorio, I. Informe Final Etapa 2: Evaluación del Impacto Ecológico del Cultivo de Aguacate a Nivel Regional y de Parcela en el Estado de Michoacán: Validación de Indicadores Ambientales en los Principales Tipos de Producción; Informe Final a la Fundación Produce Michoacán (FPM) y la AAL-PAUM; Centro de Investigaciones en Geografía Ambiental (CIGA/UNAM Campus Morelia): Morelia, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Coronado, J.A.; Bijman, J.; Omta, O.; Lansink, A.O. A case study of the Mexican avocado industry based on transaction costs and supply chain management practices Econ. Teoría Práct. 2015, 42, 137–165. [Google Scholar]

- Mas, J.F.; Lemoine-Rodríguez, R.; González, R.; López-Sánchez, J.; Piña-Garduño, A.; Herrera-Flores, E. Evaluación de las tasas de deforestación en Michoacán a escala detallada mediante un método híbrido de clasificación de imágenes SPOT. Madera Bosques 2017, 23, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, R.G.; Rodriguez-Jasso, R.M.; Ruiz, H.A.; Pintado, M.M.E.; Aguilar, C.N. Avocado by-products: Nutritional and functional properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 80, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass Avocado Board. Hass Avocado Board. 2018. Available online: http://www.hassavocadoboard.com/consumer (accessed on 26 January 2019).

- Tapia, L.M.; Larios, A.; Vidales, I.; Bravo, M.; Hernández, A. Caracterizacion hidrologica del aguacate en Michoacán. Proceedings VII World Avocado Congress. 2011. Available online: http://www.avocadosource.com/wac7/Section_08/TapiaVargasLM2011.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2019).

- INEGI. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/ (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- INEGI. Sistema Para la Consulta de Información Censal SCINCE 2010. 2012. Available online: http://gaia.inegi.org.mx/scince2/viewer.html (accessed on 3 April 2017).

- CONABIO. Estrategia para la Conservación y Uso Sustentable de la Biodiversidad del Estado de Michoacán; Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO), Secretaría de Urbanismo y Medio Ambiente (SUMA) y Secretaría de Desarrollo Agropecuario (SEDAGRO): Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rzedowsky, J. Vegetación de México, 1st ed; Limusa, Noriega Editores: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Burgos, A.; Anaya, C.; Solorio, I. Evaluación del Impacto Ecológico del Cultivo de Aguacate a Nivel Regional y de Parcela en el Estado de Michoacán. Inventarios 1974—2007 y Evaluación del Impacto Ambiental Regional. Informe Ejecutivo. 2011. Available online: http://lae.ciga.unam.mx/aguacate/# (accessed on 12 April 2017).

- Garibay, C.; Bocco, G. La Situación Actual en el uso del Suelo en Comunidades Indígenas de la Región Purépecha 1976–2005; Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo De los Pueblos Indígenas: Toluca, Mexico, 2007; pp. 1–66. Available online: http://www.inpi.gob.mx/2021/dmdocuments/situacion_uso_suelo_region_purhepecha.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- CONAPO. Índice de Marginación por Entidad Federativa y Municipio 2010. 2010. Available online: http://www.conapo.gob.mx/es/CONAPO/indices_de_marginacion_2010_por_entidad_federativa_y_municipio (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- CONEVAL. CONEVAL Informa los Resultados de la Medición de la Pobreza. 2015. Available online: https://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/Paginas/consulta_pobreza_municipal.aspx (accessed on 21 May 2018).

- Palma, J.G. Homogeneous middles vs. heterogeneous tails, and the end of the ‘inverted-U’: It’s all about the share of the rich. Develop. Chang. 2011, 42, 87–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEGI. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010. 2010. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2010/ (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, J.A. Understanding and Validity in Qualitative Research. Harvard Educ. Rev. 1992, 62, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, G. Book Review: Asking Questions: The Definitive Guide to Questionnaire Design: For Market Research, Political Polls, and Social and Health Questionnaires. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 703–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAN. Registro Agrario Nacional. Área de Visualización Geográfica. 2017. Available online: https://sig.ran.gob.mx/index.php (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- United Nation Development Programme. Human Development Reports. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/MEX (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- SIAP. Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera; Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Pesca y Alimentación: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2017. Available online: www.gob.mx/siap/ (accessed on 19 September 2018).

- USDA; AMS (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service). ERS Charts of Note (20 April). 2020. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/charts-of-note/charts-of-note/?topicId=14849 (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- Naamani, G. Global trends in main avocado market. In Proceedings of the VII World Avocado Congress, Cairns, Australia, 5–9 September 2011; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Contreras, M.; Lara-Chávez, M.B.N.; Guillén-Andrade, H.; Chávez-Bárcenas, A.T. Agroecología de la franja aguacatera en Michoacán, México. Interciencia 2010, 35, 647–653. [Google Scholar]

- Garibay, C.; Bocco, G. Cambios de Uso del Suelo en la Meseta Purépecha (1976–2005); Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales; Instituto Nacional de Ecología; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; Centro de Investigaciones en Geografía Ambiental: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2011; p. 124.

- SAGARPA. Sistema agroalimentaria de consulta, SIACON (2018) [Software]); Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Pesca y Alimentación: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2019. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/siap/documentos/siacon-ng-161430 (accessed on 12 February 2020).

- Téliz, D.; Mora, A. El Aguacate y su Manejo Integrado, 2nd ed.; Mundi-Prensa, Colegio de Posgraduados, Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo: Chapingo, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- CEDRSSA. Caso de Exportación: El Aguacate. 2017. Available online: http://www.cedrssa.gob.mx/files/b/13/54Exportaci%C3%B3n%20aguacate.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- APEAM. Exportaciones de Aguacate en el ciclo 2019/2020. 2020. Available online: http://www.apeamac.com/ (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- SAGARPA. Planeación Agrícola Nacional 2017–2030, Aguacate Mexicano (2017)—SAGARPA Mexico. 2017. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/257067/Potencial-Aguacate.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2018).

- Echánove, F.H.; Steffen, C. Globalización y Reestructuración en el Agro Mexicano: Los Pequeños Productores de Cultivos no Tradicionales; Plaza y Valdés: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Merino, L.; Hernández, M. Destrucción de instituciones comunitarias y deterioro de los bosques en la Reserva de la Biosfera Mariposa Monarca, Michoacán, México. Rev. Mex. Sociol. 2004, 66, 261–309. [Google Scholar]

- SNIF. Sistema de Precios de Productos Forestales Maderables. 2018. Available online: https://snigf.cnf.gob.mx/precios-de-productos-forestales-maderables-sipre/ (accessed on 16 April 2019).

- APROAM. Precios Sugeridos Por Kg de Fruta de Aguacate. 2021. Available online: https://aproam.com/precios-del-aguacate-marzo-2021/ (accessed on 3 April 2021).

- Madrid, L.; Núñez, J.M.; Quiroz, G.; Rodríguez, Y. La propiedad social forestal en México. Investig. Ambient. 2009, 1, 179–196. [Google Scholar]

- FIRA. Aguacate (Meseta Purépecha). 2018. Available online: https://www.fira.gob.mx/Nd/Agrocostos.jsp (accessed on 8 April 2019).

- Schlager, E.; Ostrom, E. Property-rights regimes and natural resources: A conceptual analysis. Land Econ. 1992, 68, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chávez-León, G.; Tapia Vargas, L.M.; Bravo Espinoza, M.; Sáenz Reyes, J.; Muñoz Flores, H.J.; Vidales Fernández, I.; Alcántar Rocillo, J.J. Impacto del Cambio de uso de Suelo Forestal a Huertos de Aguacate; Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias: Uruapan, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez, A.; Bocco, G.; Siebe, C. Cambio del Uso del Suelo; Red temática CONACYT sobre Medio Ambiente y Sustentabilidad: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, K.; Goldstein, B.; Gounaridis, D.; Newell, J.P. Where does your guacamole come from? Detecting deforestation associated with the exports of avocados from Mexico to the United States. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 278, 111482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huacuja, F.E. Abriendo fronteras: El auge exportador del aguacate Mexicano a Estados Unidos. An. Geogr. 2008, 28, 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez, A.; Torres, A.; Bocco, G. Las Enseñanzas de San Juan: Investigación Participativa Para el Manejo Integral de Recursos Naturales; Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, Instituto Nacional de Ecología: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2003.

- Velázquez, A.; Bocco, G.; Torres, A. Turning scientific approaches into practical conservation actions: The case of Comunidad Indigena de Nuevo San Juan Parangaricutiro, Mexico. Environ. Manag. 2001, 27, 655–665. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, C. Political Landscapes. Forest, Conservation, and Community in Mexico; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, D.; Merino, L. La Experiencia de las Comunidades Forestales en México: Veinticinco años de Silvicultura y Construcción de Empresas Forestales Comunitarias. 2004. Available online: http://ru.iis.sociales.unam.mx/bitstream/IIS/4939/1/la%20experecia%20en%20las%20comuidades%20forestales%20en%20Mexico.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2017).

- Bonilla-Moheno, M.; Aide, T.M. Beyond deforestation: Land cover transitions in Mexico. Agric. Syst. 2020, 178, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsimantov, J.; Kendall, J. Community Forestry, Common Property, and Deforestation in Eight Mexican States. J. Environ. Dev. 2012, 21, 414–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenteras, D.; Espelta, J.M.; Rodríguez, N.; Retana, J. Deforestation dynamics and drivers in different forest types in Latin America: Three decades of studies (1980–2010). Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 46, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, L.; Martínez, A.E. A Vuelo de Pájaro: Las Condiciones de Las Comunidades Con Bosques Templados en México; Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- FAO & FILAC. Forest Governance by Indigenous and Tribal Peoples. An Opportunity for Climate Action in Latin America and the Caribbean. 2021. Available online: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/es/c/cb2953en/ (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). Nature’s Dangerous Decline ‘Unprecedented’ Species Extinction Rates ‘Accelerating’. 2019. Available online: https://www.ipbes.net/news/Media-Release-Global-Assessment (accessed on 25 September 2019).

- Barsimantov, J.; Antezana, J.N. Land Use and Land Tenure Change in Mexico’s Avocado Production Region: Can Community Forestry Reduce Incentives to Deforest for High Value Crops? In Proceedings of the 12th Biennial Conference of the International Association for the Study of the Commons, Cheltenham, UK, 14–18 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Population | Average Age | Indigenous Population | Human Development Index 1 | GDP per Capita (USD) | Population Living in Poverty % 2 | Population Living in Extreme Poverty % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuevo Parangaricutiro | 20,981 | 26 | 67% | 0.65 | 8028 | 68% | 10.6% |

| Uruapan | 356,786 | 27 | 19% | 0.73 | 12,242 | 56.4% | 9.3% |

| Meseta Purépecha | 660,651 | 24 | 32% | ND | ND | 63.4% | 14.3% |

| Michoacán | 4,748,846 | 28 | 14% | 0.69 | 5147 | 59.11% | 9.92% |

| Mexico | 126,014,024 | 26 | 7% | 0.76 | 9271 | 47.54% | 8.37% |

| Palma Index in 2010 | |

|---|---|

| Uruapan | 3.05 |

| San Juan Nuevo | 0.46 |

| Michoacán State | 2.9 |

| Mexico | 2.8 |

| Cost and Profits from the Orchards in the Year 1 (USD)/ha | Cost and Profits from the Orchards in Years 2–4 (USD)/ha | Cost and Profits from the Orchards in Years 4–10 (USD)/ha | Cost and Profits from the Orchards after 10 Years and more (USD)/ha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tree planting | 44.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fertilizers | 2800 | 2800 | 2800 | 2800 |

| Maintenance and care of the plantation | 800 | 800 | 800 | 800 |

| Irrigation | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 |

| Control of pests and weeds | 1180 | 1180 | 1180 | 1180 |

| Costs of participation in the export program, agricultural insurance, and administrative costs | 900 | 850 | 850 | 850 |

| Total | 6125 | 6030 | 6030 | 6030 |

| Sales | 0 | 0 | 7600–11,800 | 14,700–22,700 |

| Balance | −6125 | −6030 | 1570–5770 | 8690–16,670 |

| Total Extension (Hectares) | Communal-Ejido Lands (%) | Extension of Lands Covered by Avocado Orchards (has) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uruapan | 101,500 | 39.6 | 16,200 |

| San Juan Nuevo | 23,500 | 55 | 7520 |

| Meseta Purépecha | 413,716 | 28.5 | 76,889 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De la Vega-Rivera, A.; Merino-Pérez, L. Socio-Environmental Impacts of the Avocado Boom in the Meseta Purépecha, Michoacán, Mexico. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7247. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137247

De la Vega-Rivera A, Merino-Pérez L. Socio-Environmental Impacts of the Avocado Boom in the Meseta Purépecha, Michoacán, Mexico. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7247. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137247

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe la Vega-Rivera, Alfonso, and Leticia Merino-Pérez. 2021. "Socio-Environmental Impacts of the Avocado Boom in the Meseta Purépecha, Michoacán, Mexico" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7247. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137247

APA StyleDe la Vega-Rivera, A., & Merino-Pérez, L. (2021). Socio-Environmental Impacts of the Avocado Boom in the Meseta Purépecha, Michoacán, Mexico. Sustainability, 13(13), 7247. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137247