Online Synchronous Model of Interpretive Sustainable Guiding in Heritage Sites: The Avatar Tourist Visit

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

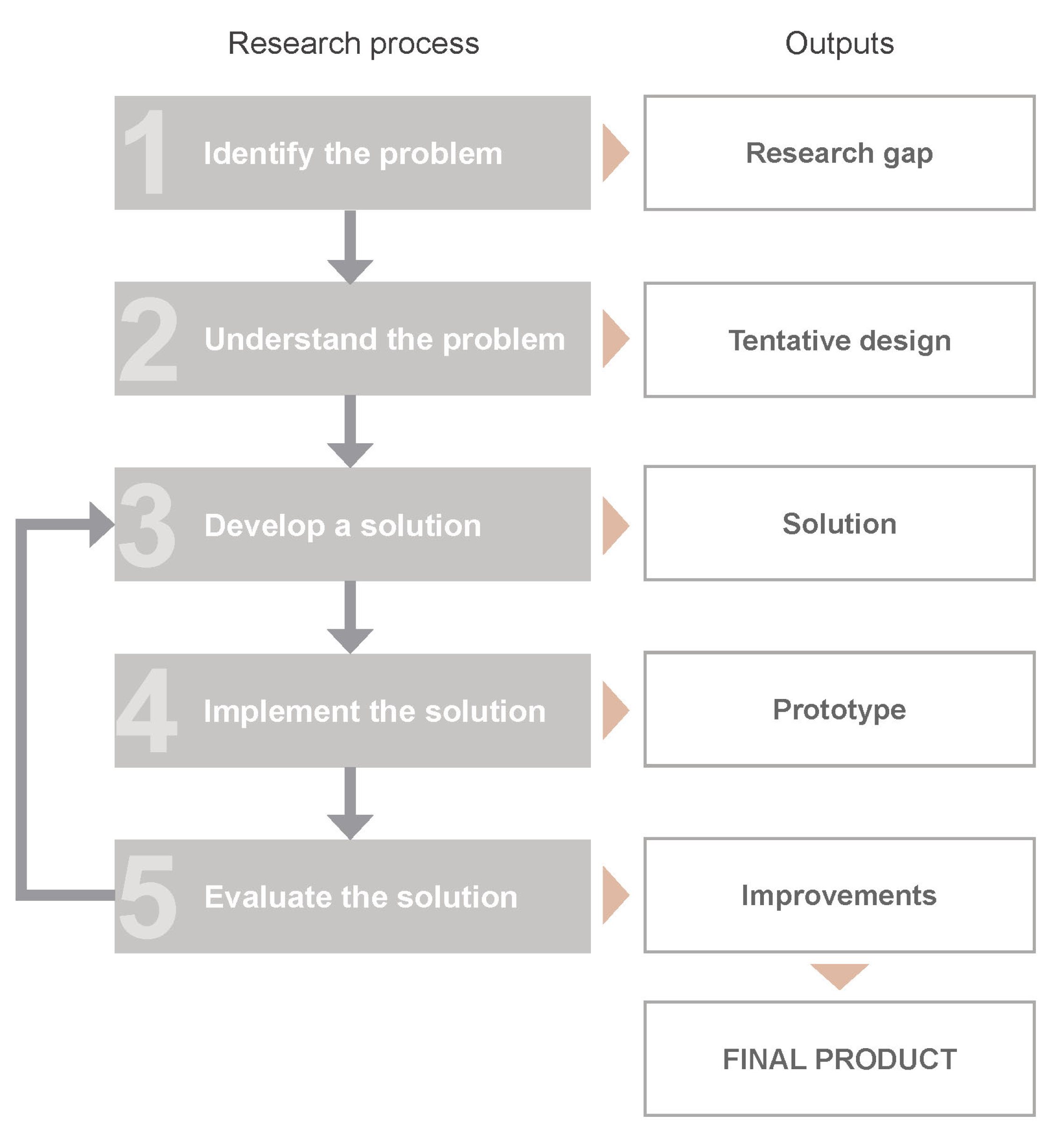

- Identify the problem: First, the traditional method of data collection and analysis was implemented to identify the problem. This analysis was based on a literature review and expert interviews. The literature review provided a useful insight into the state of the art and the conditions of museums, monuments, cultural centres, etc., during the pandemic period. It was carried out through scientific search engines, databases, digital libraries, and scientific journals. A lot of information was also retrieved from newspapers and broadcast media. In addition, open interviews were conducted with curators, heritage, and tourism managers, among others. The aim was to identify problems during the pandemic with regard to the operational procedures for visitor management.

- Understand the problem: This stage consists of recognizing the traditional process followed by visitor management and heritage interpretation sites under normal circumstances, as well as being aware of the problem of cultural disengagement and its consequences caused by the pandemic. Open interviews with experts were also carried out at this stage. A tentative design or the first idea emerged from the awareness of the problem.

- Develop a solution: Based on the problems identified in previous stages, in this one, it is proposed to design a procedure in order to carry out a live-streaming visit to heritage sites so that it is as immersive as possible and can serve as a way to develop the interpretation program of the site. The design of the visit was developed based on scientific experience and specific field works on the subject of the research group, the review of the existing scientific literature on online strategic communications, as well as consultations with experts from various fields of knowledge.

- Implement the solution: Once designed, the procedure was subsequently implemented in five heritage sites in València (Spain) of both the cultural and natural type. Preliminary prototypes were obtained from them.

- Evaluate the solution: A procedure evaluation system was developed to validate and optimize the model. Consequently, an online focus group was created, that was composed of a wide variety of experts and researchers (20) in the fields of Strategic Communication, Heritage Interpretation, and Sustainable Tourism. Based on a qualitative discussion with this focus group after each test, the procedure was evaluated on five criteria: applicability, usefulness, immersion (sense of presence: perception of “being physically there”), engagement (involvement), and enjoyment [18,19,20,21]. These participative debate sessions were intended to provide suggestions for analysis and progressive improvements of the model procedure. The feedback derived from the evaluation phase (Stage 5) allows to implement the suggested improvements and, therefore, improve the solution (Stage 3) as many times as necessary to optimize the model in a looping process (Figure 1) until obtaining the best-fitting final design.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Conceptual Bases to Solve the Problem

3.1.1. Heritage Interpretation

3.1.2. Interpersonal Communication

3.1.3. Filmmaking and Audio-Visual Language

3.1.4. Information and Communication Technologies (ICT)

3.2. Communication Process: Streamer and Receivers

3.2.1. Avatar Guide

3.2.2. Camera Operator

3.2.3. Remote Visitor

3.3. Procedure for Developing the Visit

3.3.1. Main Interpretive Theme

3.3.2. Context

3.3.3. Storytelling

3.3.4. Touring Pattern

3.3.5. Filming the Live-Stream Visit

- Big and full shots: This open shot will be used for the sequences that describe the environment and thereby giving the idea of the scale and spatiality of the place.

- Medium shot: Framing the avatar guide from the waist up to emphasize the guide’s expression; it is specifically designed for the welcoming and farewell to the visit.

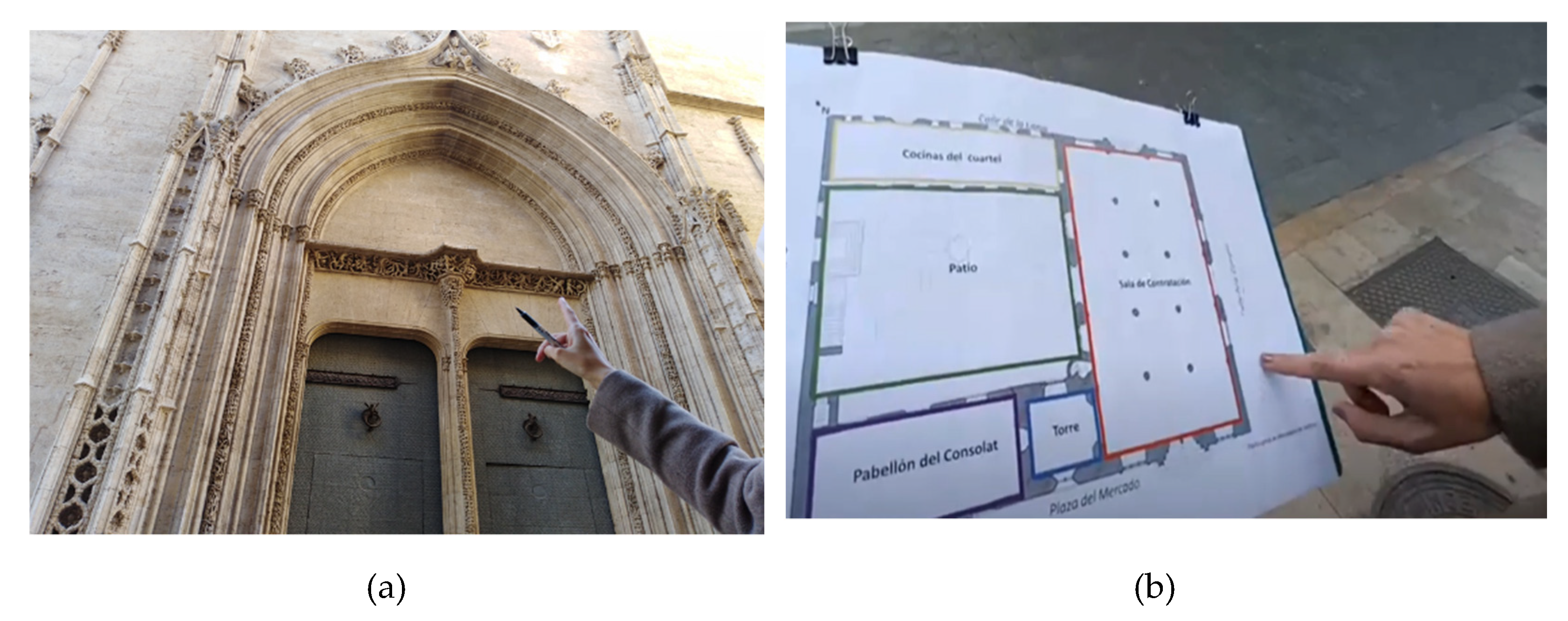

- Close-up shot: It is used to specifically highlight some detail or elements. One advantage to be highlighted is, as Das [51] suggests, that this kind of filming allows seeing details that people would normally miss. This shot can be useful to show small details about an architectural element, to explain or draw the audience’s attention to a specific object, etc. Another useful aspect of this close-up shot is the one that is employed to display complementary contextualization elements, such as documents, maps, elevations, and floor plans, etc., that are displayed to the camera at different parts of the route so that the audience is spatially oriented at all times. It is suggested that these shots include the hand of the guide showing the relevant details to be highlighted (Figure 2).

- Upside-down shot: It is characterized by the fact that the camera is directed towards the sky to show the height of the building or the facade of a monument. It gives an idea of the size and dimensions of the heritage element; it produces an effect of splendour and grandiosity (Figure 2).

- Travelling: It is a tracking shot sideway-camera movement, which, in our case, was taken while walking. The camera physically moves, following the subject. On a narrative level, carrying the camera in hand produces a great sense of realistic motion and realism. Thus, most of the visit is taken by a big shot (in which the avatar guide’s figure is not fully displayed) that shows the space as the camera moves through it, moving forward.

- Panning: This technique allows to present an image wider than the display (an expansive view that exceeds the gaze) by rotating the video camera horizontally from a fixed position. This is very useful for creating a sense of action during the avatar visit. The motion effect provided by this camera movement is similar to that of a person when he/she turns the head from left to right and it draws remote visitors into the story.

3.4. Implementing and Evaluating the Procedure

- Religious ensemble of San Juan del Hospital (Spanish Cultural Asset of National Interest);

- Palacio del Marqués de Dos Aguas—Spanish National Museum of Ceramics González Martí (Spanish Cultural Asset of National Interest);

- Valencian Archaeological Centre of L’Almoina;

- Lonja de los Mercaderes de València (UNESCO World Heritage Site);

- Túria River Natural Park (Valencian Regional Natural Protected Area).

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Network of European Museum Organisations. NEMO Report on the Impact of COVID-19 on Museums in Europe. 2020. Available online: www.ne-mo.org/news/article/nemo/nemo-report-on-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-museums-in-europe.html (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Oxford English Dictionary. Available online: www.oed.com (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Paolini, P.; Barbieri, T.; Loiudice, P.; Alonzo, F.; Zanti, M.; Gaia, G. Visiting a Museum Together: How to Share a Visit to a Virtual World. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2000, 51, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, D. Virtual Tourism. A Niche in Cultural Heritage. In Niche Tourism: Contemporary Issues, Trends and Cases; Novelli, M., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- Guttentag, D.A. Virtual Reality: Applications and Implications for Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, R. Museums in a Digital Age; Routledge: New York, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Li, X.; Li, Y. China’s “smart Tourism Destination” Initiative: A Taste of The Service-Dominant Logic. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maicas, J.M.; Viñals, M.J. Design of a Virtual Tour for the Enhancement of Llirias’s Architectural and Urban Heritage and Its Surroundings. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2017, 8, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiltshier, P.; Clarke, A. Virtual Cultural Tourism: Six Pillars of VCT Using Co-Creation, Value Exchange and Exchange Value. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 17, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hudson, S.; Matson-Barkat, S.; Pallamin, N.; Jegou, G. With or without You? Interaction and Immersion in Virtual Reality Experience. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machidon, O.M.; Duguleana, M.; Carrozzino, M. Virtual Humans in Cultural Heritage ICT Applications: A Review. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 33, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrozzino, M.; Colombo, M.; Tecchia, F.; Evangelista, C.; Bergamasco, M. Comparing Different Storytelling Approaches for Virtual Guides in Digital Immersive Museums. In Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Computer Graphics; AVR 2018; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; De Paolis, L., Bourdot, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10851, pp. 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R.; Buhalis, D.; Pletinckx, D. Visitors’ Evaluations of Technology Used at Cultural Heritage Sites. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Hitz, M., Sigala, M., Murphy, J., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilabert-Sansalvador, L.; Viñals, M.J.; Casar Furió, M.E.; Capilla Tamborero, E.; Herrero García, L.F. From On-Campus to Online Instruction in Postgraduate Built Heritage Management Studies. In INTED2021, Proceedings of the 15th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain, 8-9 March 2021; Gómez Chova, L., López Martínez, A., Candel Torres, I., Eds.; IATED Academy: Valencia, Spain, 2021; pp. 5577–5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Aken, J.E. Management Research Based on the Paradigm of the Design Sciences: The Quest for Field-Tested and Grounded Technological Rules. J. Manag. Stud. 2004, 41, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, I. Comparison of Three Methodological Approaches of Design Research. In DS 42, Proceedings of ICED 2007, the 16th International Conference on Engineering Design, Paris, France, 28–31 July 2007; CITÉ DES SCIENCES ET DE L’INDUSTRIE: Paris, France; pp. 361–362.

- Baskerville, R.L.; Kaul, M.; Storey, V.C. Genres of Inquiry in Design-Science Research: Justification and Evaluation of Knowledge Production. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 541–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzortzopoulos, P. The Design and Implementation of Product Development Process Model in Construction Companies. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Salford, Salford, UK, 2004. Available online: usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/26949 (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Lessiter, J.; Freeman, J.; Keogh, E.; Davidoff, J. A Cross-Media Presence Questionnaire: The ITC-Sense of Presence Inventory. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2001, 10, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Kort, Y.A.; IJsselsteijn, W.A.; Poels, K. Digital Games as Social Presence Technology: Development of the Social Presence in Gaming Questionnaire (SPGQ). In PRESENCE 2007, Proceedings of the 10th Annual International Workshop on Presence, Barcelona, Spain, 25-27 October 2007; Starlab: Barcelona, Spain, 2007; pp. 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni, G.; Daniel, F.; Casati, F.; Callaway, C.; Stock, O. Interactive Remote Museum Visits for Older Adults: An Evaluation of Feelings of Presence, Social Closeness, Engagement, and Enjoyment in a Social Visit. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia (ISM), San Diego, CA, USA, 9–11 December 2019; pp. 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishnavi, V.K.; Kuechler, W. Introduction to Design Science Research in Information and Communication Technology. In Design Science Research Methods and Patterns: Innovating Information and Communication Technology; CRC Press: Boca Ratón, FL, USA, 2004; pp. 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tilden, F. Interpreting Our Heritage; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Ham, S.H. Environmental Interpretation: A Practical Guide for People with Big Ideas and Small Budgets; North American Press: Golden, CO, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, L.; Cable, T. Interpretation for the 21st Century: Fifteen Guiding Principles for Interpreting Nature and Culture; Sagamore Publishing: Champaign, IL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S. Sharing Our Stories Guidelines for Heritage Interpretation; The National Trust of Australia (WA) and Museums Australia: Canberra, Sidney, 2007; Available online: www.nationaltrust.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/20110208SharingourStories.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- ICOMOS. The ICOMOS Charter on the Interpretation and Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites; 16th General Assembly of ICOMOS: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2008; Available online: www.icomos.org/charters/interpretation_e.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Brochu, L.; Merriman, T. Personal Interpretation: Connecting Your Audience to Heritage Resources; National Association for Interpretation: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz, J.; Lackey, B.; Gross, M.; Zimmerman, R. Interpreter’s Guidebook: Techniques and Tips for Programs and Presentations; UWSP Foundation, University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point: Stevens Point, WI, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shalaginova, I. Understanding Heritage. A Constructivist Approach to Heritage Interpretation as a Mechanism for Understanding Heritage Sites. Ph.D. Thesis, Branderburg University of Technology, Cottbus, Germany, 2012. Available online: core.ac.uk/download/pdf/33434544.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Norman, D.A. Things that Make Us Smart: Defending Human Attributes in the Age of the Machine; Perseus Books: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, P. Heritage: Management, Interpretation, Identity; Continuum: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild, P. Interpreting Landscape Heritage. In Proceedings of the International Symposium “Interpretation: From Monument to Living Heritage” and 2nd ICOMOS Thailand General Assembly, Bangkok, Thailand, 1–3 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster County Planning Commission. Telling Our Stories. An Interpretation Manual for Heritage Partners; Lancaster County Heritage and York County Heritage: Lancaster, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. A New Communication Model for Museums. In The Educational Role of the Museum; Hopper-Greenhill, E., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, D. A Viewpoint: The Museum as a Communications System and Implications for Museum Education. Curator 1968, 11, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallitt, D. Point of View and “Intrarealism” in Hitchcock. Wide Angle 1980, 4, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Pietroni, E. Experience Design, Virtual Reality and Media Hybridization for the Digital Communication Inside Museums. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2019, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.C. Data Communications and Computer Networks; Prentice-Hall: New Delhi, India, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Microsoft. Prepare Your Organization’s Network for Teams. Available online: docs.microsoft.com/es-es/microsoftteams/prepare-network (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Beuthel, J.M.; Bentegeac, P.; Fuchsberger, V.; Maurer, B.; Tscheligi, M. Experiencing Distance: Wearable Engagements with Remote Relationships. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, 14–17 February 2021; Acm Digital Library: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, B.; Siang See, Z.; Day, J. Crisis and Extended Realities: Remote Presence in the Time of Covid-19. Media Int. Aust. 2021, 178, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayanou, M.; Katifori, A.; Chrysanthi, A.; Antoniou, A. Cultural Heritage and Social Experiences in the Times of COVID19. In AVI 2CH 2020, Proceedings of the AVI2CH Workshop on Advanced Visual Interfaces and Interactions in Cultural Heritage co-located with 2020 International Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces (AVI 2020); Island of Ischia, Italy, 29 September 2020; Antoniou, A., De Carolis, B., Dix, A., Gena, C., Kuflik, T., Lepouras, G., Origlia, A., Raptis, G.E., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: ceur-ws.org/Vol-2687/paper2.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Staiff, R. Re-Imagining Heritage Interpretation: Enchanting the Past-Future; Routledge: New York, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hallahan, K. Seven Models of Framing: Implications for Public Relations. J. Public Relat. Res. 1999, 11, 205–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Equipment, Image and Video Composition and Script Creation. In Proceedings of the World Heritage Media/Communication Training Workshop: Passing the Culture Message, Weimar, Germany, 8–13 December 2013; Available online: whc.unesco.org/en/events/1093 (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Roussou, M. The Components of Engagement in Virtual Heritage Environments. In New Heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage; Kalay, Y., Kvan, T., Affleck, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 265–283. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, S.; Roussou, M.; Economou, M.; Young, H.; Pujol, L. Moving Beyond the Virtual Museum: Engaging Visitors Emotionally. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Virtual System & Multimedia VSMM 2017, Dublin, Ireland, 31 October–4 November 2017; IEEE: Dublin, Ireland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schofield, G.; Beale, G.; Smith, N.; Fell, M.; Hook, J.; Hadley, D.; Murphy, D.; Richards, J.; Thresh, L. Viking VR: Designing a Virtual Reality Experience for a Museum. In Proceedings of the 2018 Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Hong Kong, China, 9–13 June 2018; pp. 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ávila, L. Revista 24 Cuadros. Cómo se Compone en Cine. Available online: revista24cuadros.com/2017/11/16/principios-de-la-composicion-visual-aplicados-al-cine/ (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Das, T. How to Write a Documentary Script. A Monograph; Public Service Broadcasting Trust, UNESCO; New Delhi, India, 2007; Available online: www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CI/CI/pdf/programme_doc_documentary_script.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Buhalis, D.; Sinarta, Y. Real-Time Co-Creation and Nowness Service: Lessons from Tourism and Hospitality. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Viñals, M.J.; Gilabert-Sansalvador, L.; Sanasaryan, A.; Teruel-Serrano, M.-D.; Darés, M. Online Synchronous Model of Interpretive Sustainable Guiding in Heritage Sites: The Avatar Tourist Visit. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137179

Viñals MJ, Gilabert-Sansalvador L, Sanasaryan A, Teruel-Serrano M-D, Darés M. Online Synchronous Model of Interpretive Sustainable Guiding in Heritage Sites: The Avatar Tourist Visit. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137179

Chicago/Turabian StyleViñals, María José, Laura Gilabert-Sansalvador, Anna Sanasaryan, Maria-Dolores Teruel-Serrano, and Marino Darés. 2021. "Online Synchronous Model of Interpretive Sustainable Guiding in Heritage Sites: The Avatar Tourist Visit" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137179

APA StyleViñals, M. J., Gilabert-Sansalvador, L., Sanasaryan, A., Teruel-Serrano, M.-D., & Darés, M. (2021). Online Synchronous Model of Interpretive Sustainable Guiding in Heritage Sites: The Avatar Tourist Visit. Sustainability, 13(13), 7179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137179