Industrial Agroforestry—A Sustainable Value Chain Innovation through a Consortium Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

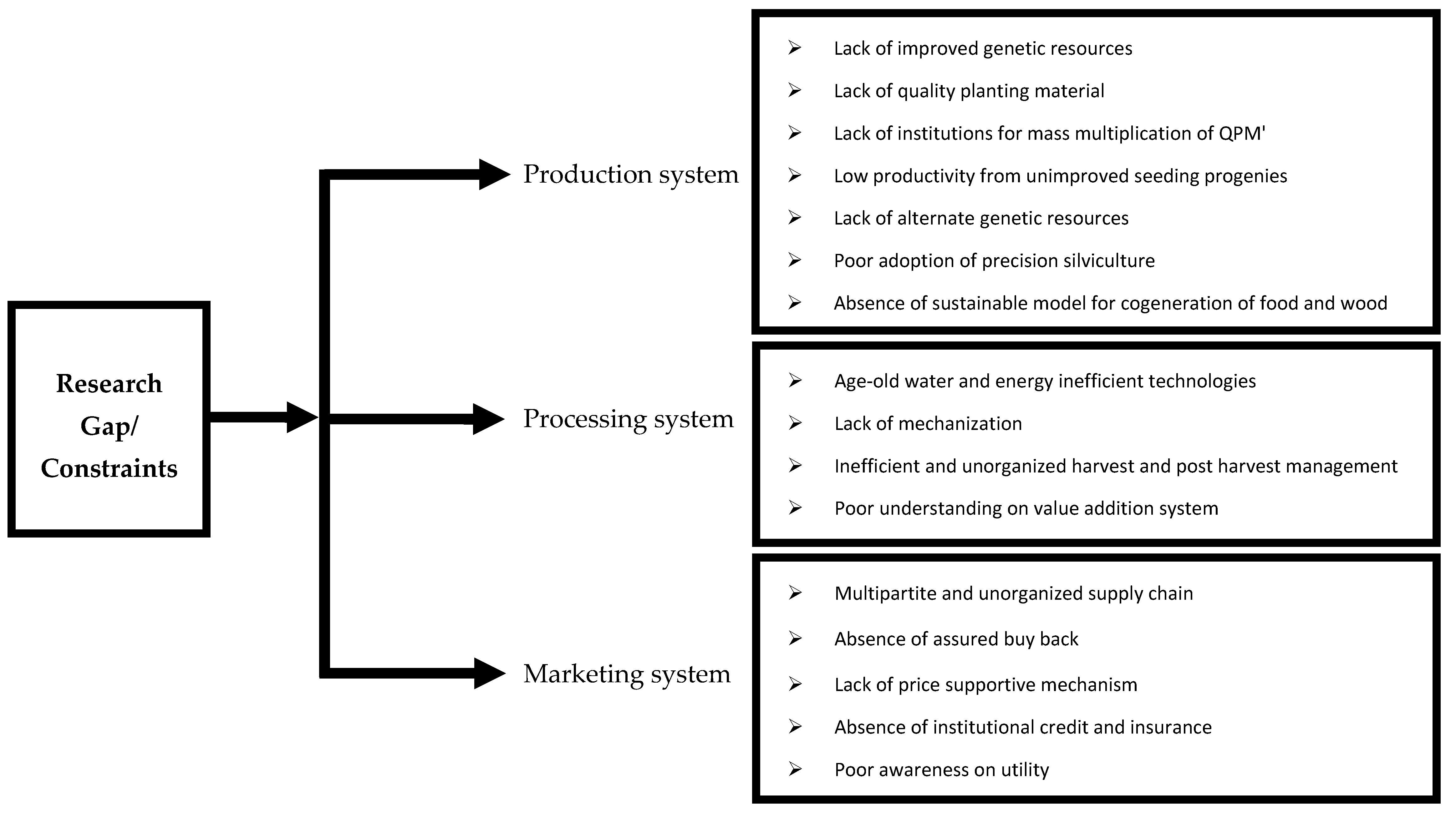

2. Research and Knowledge Gap

3. Innovations and Interventions

3.1. Technological Innovations

3.1.1. Development and Deployment of High Yielding Short Rotation (HYSR) Clones

3.1.2. Miniclonal Technology

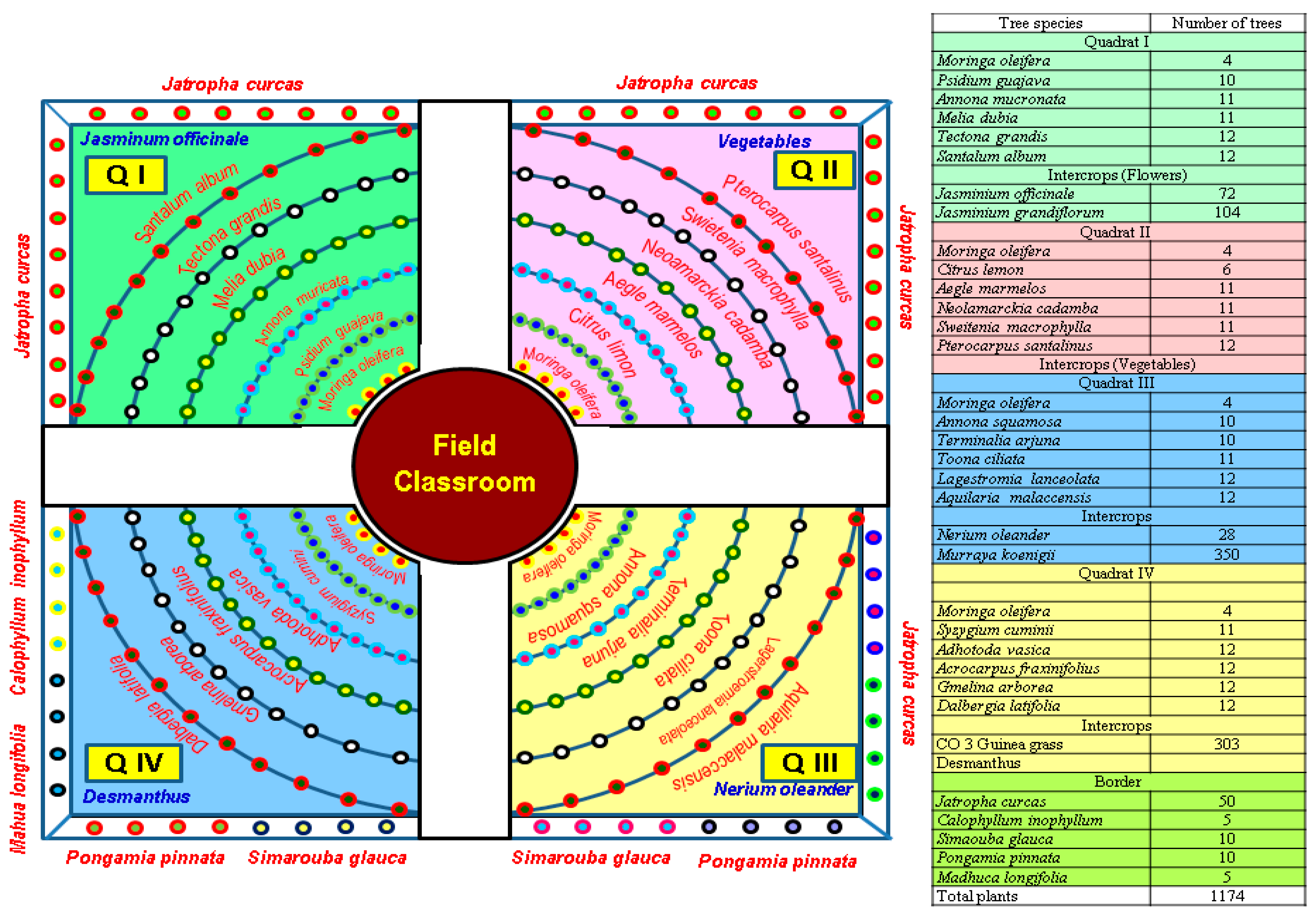

3.1.3. Design and Development of Multifunctional Agroforestry Model

3.1.4. Value Addition Technology

3.1.5. Design and Development of Machineries for Agroforestry

3.2. Organizational Innovations

3.2.1. Design and Deployment of Contract Tree Farming

3.2.2. Consortium of Industrial Agroforestry

3.3. Marketing Innovations

3.4. Business Innovations

4. Impact of Value Chain

4.1. Development of Organized Industrial Agroforestry Plantations

4.2. Productivity Improvement

4.3. Profitability Enhancement

4.4. Increased Participation of Industries

4.5. Socio-Economic Development

4.6. Environmental Amelioration

5. Sustainability and Way Forward

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Upadhyay, V.K.; Singh, M.P.; Nandawar, A.; Kushwaha, P.K.; Murthy, N.; Kumar, M. Statistics, trend and scenario of wood log import in India. Indian For. 2021, 147, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Parthiban, K.T. Industrial Agroforestry: A successful value chain model in Tamil Nadu, India. In Agroforestry Research Developments; Dagar, J.C., Tewari, J.C., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 523–537. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. India Forestry Outlook Study. In Working Paper No. APFSOS II/WP/2009/06; Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2009; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- White, A.; Sun, X.; Canby, K.; Xu, J.; Barr, C.; Katsigris, E.; Bull, G.Q.; Cossalter, C.; Nilsson, S. China and the Global Market for Forest Products—Transforming Trade to Benefit Forest and Livelihoods; Forest Trends: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, M.; Sinha, B. Impact of forest policies on timber production in India: A review. UN Sustain. Dev. J. 2016, 40, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parthiban, K.T.; Fernandaz, C.C. Industrial agroforestry—Status and developments in Tamil Nadu. Indian J. Agrofor. 2017, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Parthiban, K.T.; Seenivasan, R. Forestry Technologies: A Complete Value Chain Approach; Scientific Publishers: Jodhpur, India, 2017; pp. 1–287. [Google Scholar]

- Handa, A.K.; Dhyani, S.K. Three Decades of Agroforestry Research in India: Retrospection for way forward. Agric. Res. J. 2015, 52, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Forest Policy; Government of India, Ministry of Environment and Forests: New Delhi, India, 1988; pp. 1–56.

- National Agroforestry Policy; Government of India, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperation: New Delhi, India, 2014; pp. 1–25.

- Bansal, A.K. Sustainable Trade of Wood and Wood based products in India. NCCF Policy Paper 2021, 01/2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dhyani, S.K.; Handa, A.K. Area under agroforestry in India: An assessment for present status and future perspective. Indian J. Agrofor. 2013, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood, R.; Lipton, M.; Newell, A. Farm size. In Handbook of Agricultural Economics; Pingali, P.L., Evenson, R.E., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 4, pp. 3323–3397. [Google Scholar]

- Parthiban, K.T.; Sudhagar, R.J.; Fernandaz, C.C.; Krishnakumar, N. Consortium of Industrial Agroforestry: An institutional mechanism for sustaining agroforestry in India. Curr. Sci. 2019, 117, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthiban, K.T.; Krishnakumar, N.; Fernandaz, C.C. Forest Business Incubator—An Innovative Institution for Business Development in Forestry and Agroforestry Sector in India. Indian For. 2020, 146, 584–591. [Google Scholar]

- Parthiban, K.T.; Ramah, K.; Sivakumar, K.; Rajeshwar, R.G. Multifunctional Agroforestry (Ecosystem Services); Jaya Publishing: Delhi, India, 2019; Volume 1, p. 343. [Google Scholar]

- Parthiban, K.T.; Srivastava, D.; Keerthika, A. Design and development of multifunctional agroforestry for family farming. Curr. Sci. 2021, 120, 27–28. [Google Scholar]

| Sl. No | Species | Improved Varieties | Productivity (MT/ha) | Duration (Years) | Industrial Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Casuarina | MTP-1 MTP-2 CJ-01 | 150 | 3–5 | Pulp, paper, biomass power, construction industries |

| 2. | Eucalyptus | MTP-1 | 130 | 5 | Paper |

| EH LBT 01 | 150 | 5 | Plywood, pulp | ||

| EG-01 | 150 | 5 | Plywood core, face veneer | ||

| 3. | Melia | MTP-1 | 175–200 | 5 | Plywood |

| MTP-2 | 200–250 | 2 for pulp, 6 for ply | Pulp, ply | ||

| MTP-3 | 100 | 8 ply | Face veneer | ||

| 4. | Kadam | MTP-1 | 100 | 6 | Plywood |

| 5. | Dalbergia sisoo | DS-18 | 150 | 6–8 | Pulp, energy, timber |

| 6. | Toona ciliata | TC-02 | 150 | 6 | Plywood |

| 7. | Gmelina arborea | FCRI GA-08/09 | 500 kg/tree | 6 | Packing case, timber |

| 8. | Teak | MTP TK-07 | 150Cubic Feet/tree | 15 | Timber |

| 9. | Red Sanders | TNRS-01 | 100 kg heartwood/tree | 16–18 | Timber |

| Sl. No | Traditional Technology | Mini Clonal Technology |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Reduced rooting % | Increased rooting % |

| 2. | Poor quality root system | High quality root system |

| 3. | Variation in field growth | Uniform growth in the field |

| 4. | More gestation period for propagation | Less gestation period almost half |

| 5. | Larger area are required | Less area is required |

| 6. | Root promoting hormones required | No growth hormones required |

| S.No. | Species and Clone | Specifications (GBH) (Meters) | Rate/MT USD |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Plywood Utility | ||

| 1. | Melia dubia (MTP-1, MTP-2 and MTP-3) | 0.45 and Above | 117 |

| 0.30 to 0.43 | 68 | ||

| <0.30 | 41 | ||

| 2. | Eucalyptus (EH-LBT-01) | 0.45 and Above | 82 |

| 0.30 to 0.43 | 48 | ||

| <0.30 | 41 | ||

| 3. | Toona ciliata (MTPTC-02) | 0.45 and Above | 110 |

| 4. | Swietenia macrophylla (MTPSM-20) | 0.45 and Above | 96 |

| 5. | Neolamarckia cadamba (MTP-1) | 0.45 and Above | 89 |

| 6. | Acrocarpus fraxinifolius (FCRIAF-07) | 0.45 and Above | 82 |

| B | Timber Utility | ||

| 1. | Teak (MTPTK-07, MTPTK-21, MTPTK-16) | 0.60 to 0.73 | 220 |

| 0.76 to 0.88 | 247 | ||

| 0.91 to 1.21 | 344 | ||

| 1.21 and Above | 516 | ||

| 2. | Gmelina arborea (FCRIGA-08) | 0.60 to 1.06 | 110 |

| 1.06 and Above | 165 | ||

| 3. | Acacia hybrid | 0.91 to 1.19 | 123 |

| 1.21 and Above | 165 | ||

| C | Matchwood Utility | ||

| 1. | Ailanthus excelsa (MTPSS-07) | 0.60 and Above | 82 |

| D | Pulpwood Utility | ||

| 1. | Casuarina (MTP-1, MTP-2) | 0.12 to 0.20 | 75 |

| 2. | Eucalyptus (MTP-1, EG-1& 2) | 0.12 to 0.40 | 75 |

| E | Biomass Energy | ||

| 1. | Subabul (FCRI LL15) | 0.05 to 0.40 | 48 |

| 2. | Other Species | 0.05 to 0.40 | 48 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parthiban, K.T.; Fernandaz, C.C.; Sudhagar, R.J.; Sekar, I.; Kanna, S.U.; Rajendran, P.; Devanand, P.S.; Vennila, S.; Kumar, N.K. Industrial Agroforestry—A Sustainable Value Chain Innovation through a Consortium Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137126

Parthiban KT, Fernandaz CC, Sudhagar RJ, Sekar I, Kanna SU, Rajendran P, Devanand PS, Vennila S, Kumar NK. Industrial Agroforestry—A Sustainable Value Chain Innovation through a Consortium Approach. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137126

Chicago/Turabian StyleParthiban, Kallappan Thangamuthu, Cruzmuthu Cinthia Fernandaz, Rajadorai Jude Sudhagar, Iyapillai Sekar, Subramani Umesh Kanna, Periyasamy Rajendran, Pachanoor Subbian Devanand, Subramaniam Vennila, and Nandhakrishnan Krishna Kumar. 2021. "Industrial Agroforestry—A Sustainable Value Chain Innovation through a Consortium Approach" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137126

APA StyleParthiban, K. T., Fernandaz, C. C., Sudhagar, R. J., Sekar, I., Kanna, S. U., Rajendran, P., Devanand, P. S., Vennila, S., & Kumar, N. K. (2021). Industrial Agroforestry—A Sustainable Value Chain Innovation through a Consortium Approach. Sustainability, 13(13), 7126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137126