Abstract

This theoretical paper presents a review of existing literature on the Social Investment (SI) approach to social policy and its underlying and under-explored territorial dimension. The SI approach has been debated and promoted mainly at national and supranational level, while the territorial dimension has been relatively underestimated in the policy as well as in the academic debate. A place-sensitive approach should be included within the analytical framework when addressing the territorial articulation of SI, as territorial-related variables may foster or hinder SI policies. Therefore, we provide a theoretical frame to articulate the territorial dimension of SI, and we discuss relevant points of contact between Social Investment and Territorial Cohesion. First, we provide a critical discussion about Social Investment approach, with the simultaneous aim of highlighting the gaps and the flaws, among which we focus on the territorial dimension of these policies. Second, we argue that this territorial dimension is related to the interaction between four main factors: (1) The reliance on the provision of capacitating services; (2) the process of institutional rescaling; (3) the persistence of spatial inequalities at subnational levels; and (4) the characteristics of the knowledge and learning economy. Third, we explore the relationship between place-sensitive Social Investment and Territorial Cohesion, discussing potential implications for sustainable development. The work is a theoretical reflection based on the HORIZON2020 project COHSMO “Inequality, Urbanization and Territorial Cohesion: developing the European social model of economic growth and democratic capacity”.

1. Introduction

This theoretical paper proposes a reflection on the territorial sensitivity of Social Investment (SI) policies, based on the literature review on the relationship between SI and Territorial Cohesion (TC), carried out in the framework of the Horizon2020 project COHSMO—“Inequality, Urbanization and Territorial Cohesion: developing the European social model of economic growth and democratic capacity?”.

The Social Investment (SI) perspective [1,2,3] has been debated and promoted mainly at national and supranational level, while the territorial dimension of this approach has been relatively underestimated in policymaking as well as in the academic debate [4]. In the article, we explore the relevance of the territorial dimension within SI strategies, laying a theoretical bridge with the debate on Territorial Cohesion that may have strong potential implications on the European tools for sustainable territorial development.

We seek to unpack the territorial articulation of SI, as a consequence of both the increasing relevance of local and the subnational governance levels in social policy provision and of the role of contextual specificities in the configuration of social risks. This view combines factors of social inclusion, territorial cohesion, and economic growth in a multi-scalar setting. The main questions that drive our reflections are: How do territorial features affect the chances of implementation and success of SI policies? Is the SI perspective adaptable to territorial specificities? What connections between a place-sensitive SI and the debate on TC could drive sustainable development?

In the present contribution, after a critical discussion of the Social Investment approach in welfare policies, we first argue that the territorial dimension is related to the interaction between four main factors: (1) The reliance on the provision of capacitating services; (2) the process of institutional rescaling; (3) the persistence of spatial inequalities at subnational levels; and (4) the characteristics of the knowledge and learning economy. We then explore the relationship between territorial cohesion (TC) and place-sensitive social investment. We argue that the SI approach is complementary to the more infrastructure-focused TC regional planning concept. The SI approach benefits from the TC lenses of regional specifics and, more importantly, from the sensitivity for regional disparities and balancing socio-economic development. Accordingly, place-sensitive SI strategies could mitigate regional and spatial disparities, thus contributing to sustainable development in European territories.

2. Methods and Materials

The contribution is based on the review of existing literature [5] on the link between: (a) The SI approach to social policy and TC in the EU Agenda and (b) the promotion of social policy provision based on a SI approach at national and local level. The review has been explorative and, in order to analyse the complex linkages, an objective-focused narrative review approach was adopted [6]. Thereby, we reflect on the nuances of the European and academic debate on Social Investment and highlight the connections and complementarities with Territorial Cohesion. The academic documents considered were extracted through the SCOPUS database, using “Social Investment” and “Territorial Cohesion” as main strings for articles issued from 2000 to 2020. In order to understand the territorialized impact of SI approach, we then narrowed down the selection to those articles referring to three specific policy fields: Active Labour Market Policies, Early Childcare Education and Care, Vocational and Educational Training. These policy fields result particularly suitable to reflect on the territorial dimension of SI policies, since the impacts of these policies are measurable at diverse territorial scales. For policy and strategy documents we looked to the European Commission [7] and especially the crucial ESPON project publications [8,9]. This was complemented by an additional literature review on the conceptual layering related to the “black box” or “elusive notion” of Territorial Cohesion [10,11]. The focus in extracting information has been mostly on the existing or potential contact points between TC and SI approach, as well as on their discrepancies, with a continuous and clear reference to their impact in enhancing equity among territories.

3. The Social Investment Approach

The SI approach arose at the end of the 1990s as a normative approach to counterbalance neoliberalist trends towards austerity policies promoting retrenchment in European welfare expenditure [1,2]. In the SI approach, the welfare state is seen not as an obstacle, but rather as an actor of coordination, promotion, and stimulation to economic development [12,13]. Moving away from the dominant neoliberal paradigm, Giddens and Esping-Andersen et al. refer to SI contributions within a positive theory of the (nation) state. Herein, the state should assume both a redistributive function, that provides social protection to citizens in need, as well as a capacitating function through services promoting human capabilities and work–life balance [12]. In the SI perspective, the development of human capital through education and training represents the core of a policy mix that aims at preparing individuals to face social risks, rather than only compensating them when they already experience these risks [2,14]. The concept of human capital refers to knowledge, skills and competencies embodied in individuals that promote personal, social and economic well-being [1]. However, the SI approach does not support substituting conventional income guarantees (like minimum income schemes and unemployment benefits). The minimization of poverty and promotion of income security is a precondition for the effectiveness of SI policies [12].

SI can be viewed as a paradigmatic change in the field of social policies. Social policy interventions should shift from exclusively protection-oriented to integrating prevention in policies by preparing individuals to face the less predictable and changing configuration of contemporary social risks. This prevention is to be reached by adopting a life course perspective that promotes (1) the development of skills and human capital through (lifelong) education and training [12], (2) participation in the labour market in high-quality jobs, (3) work–life balance and (4) female employment. This empowerment of citizens and workers should also lead to more socially and economically prosperous societies. This shift from protection to coordinated activation in social policy fields is not a prerogative of the SI approach, but it has characterized the programs of several governments in European countries, especially the Nordic ones. The ambitious goals of SI must be pursued through a comprehensive policy mix, encompassing education policies, selected labour market policies, poverty alleviation and family policies [14,15,16].

As old welfare policies base benefits on traditional ways of wage labour, the new socio-economic conditions challenge these policies to the point where these old policies are not only insufficient, but also unsustainable. Traditional policy financing schemes and support systems that rely on linear work-biographies, unpaid care work, and constant economic development do not keep up with the requirements of the knowledge economies emerging in European countries as well as the socio-demographic shifts influencing age distribution, family composition and well-being. As a consequence, temporary (relative) poverty, housing deprivation, precarious working arrangements, changes in care-work reconciliation arrangements and worsening living conditions of elderly people are spreading and becoming structural issues affecting an increasing share of the population [17].

SI proposes a way to deal with these challenges to welfare and social justice by changing old welfare state provisions into a more dynamic public investment in people [7]. Furthermore, the SI approach considers social policies as productive factors allowing to combine social inclusion and economic competitiveness [1]. By investing in people combined with traditional social protection, welfare systems become more sustainable as they adapt to the new socio-economic developments and meet the needs of future generations [18]. Specifically, a key element of SI is to increase social inclusion through education and work providing the population with specific and general skills in order to participate in a more flexible labour market [19,20]. So, according to the SI approach, social policy should not only protect individuals from the perils of the labour market but should prepare them to navigate an ever-changing society [21].

In the SI approach, social policy is conceived as a trampoline instead of a safety net, following a logic of “preparing” rather than “repairing”. This goal is expected to achieve positive results both at individual and societal levels. In fact, by enabling individuals to participate in the labour market (individual level), these policies promote the increase of national income, reduce long-term reliance on social benefits, lowering the budgetary pressure, and encourage new forms of business investment. SI strategies aim at not only creating any jobs, but rather at creating high-quality jobs. These are jobs that have stable and good working conditions as well as adequate remuneration [22].

Moreover, SI advocates for equal opportunities, with particular attention paid to gender issues: Work–family reconciliation policies are needed to foster both cognitive development of young children and the participation of mothers in paid work [14,23,24]. Thereby, the SI approach addresses key challenges of new labour markets and tries to tackle old as well as new inequalities, that traditional welfare policies struggle to mitigate.

Overall, the SI approach implies a shift in the social protection, from the collective to individual responsibility [21]. In other words, social investment should create the ideal conditions for individuals to invest in their own human capital preventing (new) social risks. This aspect may also mean that responsibility is put more onto individuals’ shoulders. Herein, the role of social protection within the SI approach plays a key role, following two opposite interpretations [25]. In a more liberal view, SI should replace the traditional forms of social protection. Individuals, thanks to their human capital, are considered able to cope with the downfalls of life or the transition periods. Or, as in the model followed by Scandinavian countries, SI and traditional social protection should be implemented together, since income security is a precondition for an effective SI strategy [12,21]. This constitutive ambiguity of the SI perspective is also manifested in the varieties of SI reforms and trajectories displayed across countries [26].

Scholars already highlighted that the achievement of far-reaching SI objectives of growth and inclusion relies on a complex policy mix cutting across different policy fields and forms [27]. The inherent multidimensionality underpinning the SI approach is also recognised by SI prominent advocates [2,26]. Hemerijck argues that interventions follow three distinctive policy functions: Stocks, flows and buffers, intervening through the various life course stages. Stock is represented mainly by the human capital, namely capacitating interventions aiming at enhancing and maintaining skills and capabilities over the life course. Thus, a stock function includes early childhood education and care, general education, post-secondary vocational training, university education and lifelong learning. All these services are targeted to guarantee future productivity and social inclusion. Flows’ goal is assuring the highest levels of employment participation for both genders, which means acting as a bridge during specific life phases, such as from school to work or during parental leaves and other delicate times of life transitions. Finally, buffers serve to secure income protection and economic stability. These policies mostly coincide with the traditional forms of social protection. In this mix, policies complement each other, as they provide better returns when all three functions are aligned to a common goal of SI. The main idea is that certain institutional forms involved in the delivery of SI policies are interdependent; when jointly present, they reinforce each other and contribute to improve employment and well-being [14,18].

4. Flaws and Pre-Conditions of Social Investment

Even though SI aims to lift individuals and societies up, there are some pitfalls to be considered. If the economic impact becomes the dominant consideration for expenditure, programme design and policy targets, there is a risk of fundamental changes in the priorities of social policies. Such changes could neglect the traditional and compensatory interventions that do not imply a direct and immediate economic return [2]. This means that social spending could be directed to particular fields, which are eligible to show an immediate economic return. The paradoxical result can be an increase in inequalities via social policies, as the SI approach could give less importance to goals that are not pertinent to economic rationality.

Overall, three main arguments usually arise to discuss the SI perspective critically [21]:

- Leaving out/behind non-productive people/people outside of labour markets (e.g., frail people, people with disabilities and/or illnesses): n the SI approach, the participation to labour market is the key for the social inclusion. For example, non-employed persons in charge of taking care of family’s dependent members are at risk of poverty and social exclusion even more so under the investment scheme [28].

- Complexity of individual responsibility: Putting responsibility at the centre of SI means to possibly foster conditional and disciplinary policies. Given the thin line between (a lack of) effort and societal circumstances, defining individual responsibility is neither simple nor straightforward. “A narrow view of responsibility denies the context-specific nature of human agency and the unequal distribution of opportunities, which in itself shapes the range of choices open to people” [21] (p. 7).

- Cementing inequalities (Matthew effect): Under the Matthew effect, social groups with already high socio-economic status benefit the most from investment policies [29]. Without careful policy design, SI would fortify social inequalities instead of fostering social mobility. Childcare policies are an explicative example of this effect. Most childcare services are only available to those families with two already working parents. However, dual earner-ship is not equally dispersed. Lower income households with only one parent working will be more likely to be excluded from these conditioned services. In these ways, investment in education and childcare may then exacerbate inequalities and existing divisions between socio-economic groups [30,31] and also among territories [32,33].

Failures of the SI approach have been usually interpreted as a consequence of a wrong implementation or interpretation of the SI paradigm [28,34,35]. Instead, Solga has observed that the feasibility of SI strategies depends on the specific configuration of the interdependencies among the education system [27], the labour market and social inclusion policies. Kazepov and Ranci also highlight how SI policies need a set of pre-conditions in order to fulfil both economic and socially inclusive goals [35]. Their work suggests that sometimes, as in the Italian case, SI policies not only did not reach their goals, but have even had perverse contradictory effects in the absence of the necessary pre-conditions. Three main contextual preconditions have been identified as necessary for SI policies to work effectively [35]:

- Education system and labour market should share the same orientation towards high skill employment and work interdependently. Structural disconnection between these two systems can lead to mismatches between skill demand and education, resulting in poor employability and social integration.

- Both households and labour markets should show relatively high levels of gender parity. This is necessary to avoid gendered Matthew effects in care-work conciliation and work–life balance.

- Labour market and social protection systems should strive to include people in the labour market by providing them with opportunities for requalification and by ensuring good-quality employment to prevent social exclusion.

SI policies may have ambiguous and even unexpected negative impacts on both economic growth and equal opportunities due to the lack of crucial structural conditions. This raises the awareness for possible mismatches in policy results creating vulnerabilities and disadvantages [18]. Aside from a policy focus, this also calls for the adoption of territorially differentiated approaches as national, regional and to some extent local contexts have key implications for sustainable policies, economic growth, social exclusion and territorial cohesion. However, despite the recognition that SI policies can only be implemented at the local level—as they strongly rely on services and in-kind benefits provision [1]—research contributions specifically focused on the territorial dimension of SI are limited. In the following section, we elaborate precisely on the missing conceptual connection between SI approaches and territories.

5. The Neglected Territorial Dimension of Social Investment

Neglecting the territorial articulation of SI may lead to ineffective interventions, the reproduction of inequalities or disadvantages, thus negatively affecting cohesion within and across territories. This issue brings the debate on SI and its lack of spatial sensitivity in contact with the literature on TC (see Section 6), which we understand as “ the process of promoting a more cohesive and balanced territory, by: (i) Supporting the reduction of socioeconomic territorial imbalances; (ii) promoting environmental sustainability; (iii) reinforcing and improving the territorial cooperation/governance processes; and (iv) reinforcing and establishing a more polycentric urban system” [36] (p. 10).

As for SI, we follow the conceptualisation by Kazepov and Cefalo [37] and argue, within the frame of the project COHSMO [38], that this territorial dimension under TC is related to the interaction between four main factors: (1) The reliable delivery of capacitating services; (2) the long-term process of institutional rescaling affecting European welfare states; (3) the persistence of spatial disparities among subnational territories and (4) the characteristics of the expanding knowledge economy.

5.1. Delivery of Capacitating Services

According to Kenworthy [39], SI addresses the changing social risks emerged in the post-industrial society through the provision of enabling social policies, mainly as tailored in-kind benefits in form of services. The provision of capacitating social services aims at the early identification of problems and at equipping citizens with the capabilities of orientating flexible labour markets and de-standardized life courses. This is why SI advocates for resources to be invested, among others, in childcare, education and training at secondary and tertiary levels, lifelong learning and active labour market policies [2]. The emphasis on service delivery also presumes the public organisation and/or co-ordination of the actual production of those services [40], thus resonating with a positive theory of the welfare state. However, one should bear in mind that services may have ambiguous impacts on inequalities [30]. Recent studies found that traditional cash transfers are more redistributive than investments in service and educational provision [33]; for instance, a higher investment in tertiary education may turn out to be more pro-rich than redistributive. Since in many countries the participation of middle- and higher-income groups in this educational sector is higher than it is for low-income groups, the well-off tend to reap the main benefits from the investment. This aspect shifts the focus on the design and implementation of SI measures, including the territorial articulation of service delivery.

In general, SI policies, as strongly relying on service provision, are better managed and provided at the local level [1], since this is the scale at which the needs arise with the possibility of being more context-sensitive than nationally standardized schemes centrally designed and managed. The local level is in fact considered the ideal dimension to recognise and meet social needs, to create networks, and to mobilise resources [41,42]. All in all, local governments in urban and rural areas are often tasked with providing integrated and quality social services to ensure their active social and economic inclusion as well as to further social cohesion.

Service-intensive welfare policies tend to maximise territorialisation effects, especially when compared to transfer-based measures that are usually managed on a central level [43]. On the one hand, subnational contexts can become arenas for innovative solutions to social challenges [44]. On the other hand, recent contributions challenged the consideration of local as ideal dimension for the recognition of social needs, warning against the risk of falling into “the local trap”, i.e., the a priori assumption that the local scale is always preferable to larger scales or centralisation in social policy implementation [45]. Decentralised service provision can entail reduced accountability, public de-responsibilisation and increased territorial differences [40]. Moreover, in the absence of a definition of enforceable social rights and/or of minimum standards of intervention, local policy innovation may further increase inequalities among citizens, depending on where they live [46].

The request for tailored interventions and fast adaptation of service delivery adds another layer of complexity to welfare service delivery. Therefore, when arguing for the inclusion of the territorial dimension in the SI frame, we need to consider the multi-scalar organisation of welfare provisions [4]. The specific multilevel setup of a specific welfare regime plays a crucial role in service delivery and has in turn an impact on territorial differences.

5.2. Institutional Rescaling

It is important to notice that differences in the institutional settings exist not only between, but also within, countries. Specific processes of territorial re-organisation of social policies started developing at the end of the 1970s [47]. On the vertical dimension, those processes implied the territorial reorganisation of regulatory powers, along a general trend of decentralization and greater relevance attributed to subnational scales of governance. On the horizontal dimension, the multiplication of actors involved in the design, funding, management and implementation of social policies was observed. The multiplication of actors was accompanied by an increasing role of non-governmental actors like civil society associations and commercial providers. The combined effect of these processes has been defined as the subsidiarisation of social policies [47], pointing out the complex multilevel governance solutions to the needs addressed by welfare policies. Subsidiarisation increases the demand of vertical coordination among scales, as well as horizontal coordination among different actors involved in the provision of benefits and services. Subsidiarity implies that matters ought to be handled by the smallest of lowest competent authority, meaning that the central state should perform only those tasks that cannot be performed effectively at a lower level. Additionally, since the 1990s, the political agenda of the European Union has been increasingly characterized by efforts to strengthen its democratic legitimacy: Particular programmes and tools aimed at involving civil society in the decision-making process, both at European and local levels, and in different policy sectors.

Overall, processes of subsidiarisation and European integration redesigned the role of the central (nation) state government and at the same time attributed more relevance to supra- and subnational scales of governance. The central role of local scales and cities brought about the development of local welfare systems with different impacts on social inequalities and vulnerabilities [41,48]. In turn, this gave rise to different profiles of the person in need; varying mixes of actors, interventions and stakeholders involved; and diverse approaches for social policy provision.

Again, the recognition of rescaling and subsidiarisation processes should not be interpreted as a form of localism denying the relevance of central authorities, but rather opens the door to consider complex multilevel governance arrangements. Still, rescaling dynamics can create the conditions for developing effective and localised solutions to social needs, yet they entail some critical aspects. As observed by Sabatinelli and Semprebon [32], rescaling reforms have not always brought about a balanced attribution of responsibilities among the various institutional levels involved in the regulation, financing, planning and provision of social services. Moreover, re-allocation of these functions has not always been accompanied by an adequate parallel attribution of resources. Finally, in some countries, the central state has recently regained a more prominent role in steering policies [49], sometimes due to the economic crisis of 2008 and following austerity measures. As a consequence, if cities have a front-line position in the provision of services, this/their autonomy may come with shrinking resources, due to the fact that the financing of measures and interventions has been, in many EU countries, increasingly controlled at the central level [43].

Overall, the role that SI attributes to the welfare state in coordinating the provision of capacitating services, has to be declined with respect to the scalar configurations of institutions and actors, since different levels of government and combinations of public and private actors are involved in the design and implementation of social policies. Rather, cities and local welfare actors are the entry points into structures of multilevel governance, which can provide investment-related interventions. Looking at local distributions of welfare in view of downward rescaling as well as recentralization trends further stresses the need of avoiding assumptions of internal homogeneity of the SI policy design [1].

5.3. Spatial Disparities

Extensive research on spatial inequality in the EU shows how regions and cities have responded to labour market and socio-economic challenges [50,51]. Strong and persisting territorial disparities mark a territorial patchwork of diverging income and labour market participation in Europe [52]. The divide between stagnating, industrialised, remote regions and privileged productive ones, normally metropolitan areas [36], has been complicated by the impact of the Great Recession. As a number of capital metropolitan regions have been severely hit, some rural and intermediate regions have displayed more resilience [52].

As stated in the seventh European report on economic, social and territorial cohesion [53], from 2008 onwards, regional disparities in employment and unemployment rates widened as did those in GDP per head. In 2014, disparities in employment started to narrow, followed by disparities in GDP per head in 2015. All in all, spatial disparities in socio-economic conditions remain highly pronounced, so that groups of regions can be distinguished, determined by the interaction between economy-wide forces that define the overall ladder of possibilities, and a variety of regional characteristics [50]. This has also led to the identification of low-income and low-growth regions, as well as Inner Peripheries [9], characterised by a combination of disadvantages, ranging from economic and demographic conditions to the access to services and connectedness to relevant social networks. In a similar vein, research on youth unemployment showed that EU regions where young people experience more difficulties in entering the labour market tend to cluster close to each other [54]. In this light, Atkinson et al. and Ranci stress the importance of regional and place-based indicators in comparative research on poverty and inequalities [47,55], as local conditions can have a crucial impact on transitions and individual opportunity structures.

Scholars recognise that high levels of spatial disparities and economic polarization threaten economic progress and social cohesion [56,57]. The core of the SI perspective lies in the promotion of both growth through labour market participation and increased social cohesion. In this view, equal opportunities and reduced inequalities are crucial in order to realize the potential of citizens [2]. However, spatially blind SI interventions may even contribute to produce new social inequalities or aggravate existing ones in a sort of ‘territorial Matthew effects’ [58].

5.4. Knowledge Societies

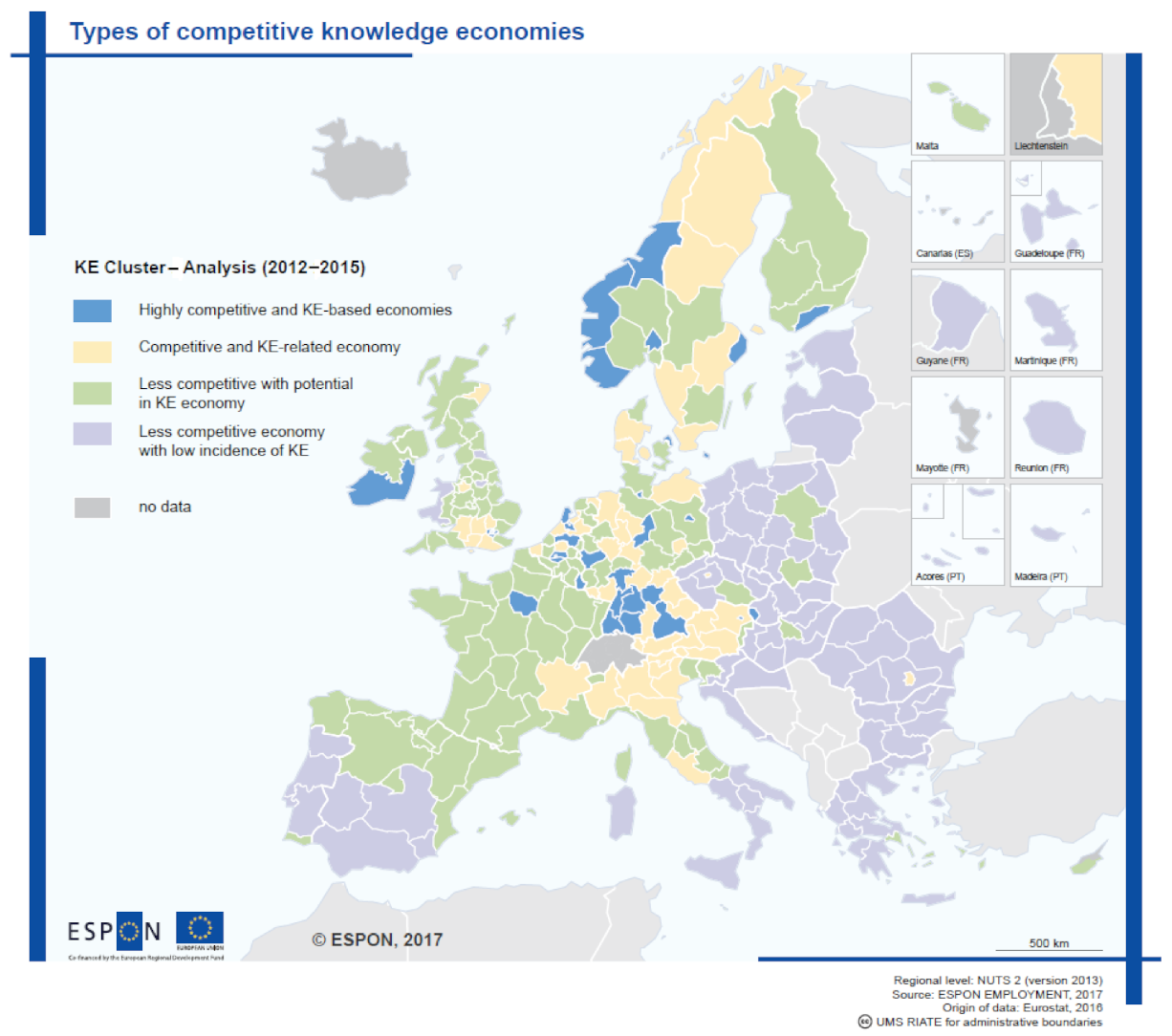

SI emphasizes skill development and facilitation of employment, especially in high-productivity service sectors and knowledge economies where the capacity to learn is crucial for economic performance [20,59,60], political participation and socio-cultural integration. The concept of knowledge economy comes with particular territorial implications [5], see Figure 1, as it entails a high demand for specialised and highly skilled labour, for example in engineering, information and communication technologies. Knowledge economies also produce spill-over effects for the creation of jobs in related sectors and foster the “upskilling” of workers [8]. In this view, competitiveness and skill formation have an important spatial dimension that emerges in the establishment of regional innovation systems. Those systems are localised networks of actors and institutions in the public and private sectors whose activities and interactions generate, import, modify and diffuse new technologies within and outside the region [61]. In particular, large metropolitan areas and their suburbs are centres of agglomeration, specialization and cumulative advantages that show strong dynamism regarding income and employment creation [62]. However, technological developments and regional innovation also tend to reinforce territorial divergence in incomes and jobs [63]. The localised economic dynamic leads to a growing demand for higher skilled workers in certain regions, consequently pulling labour force out of other regions. The presence of a competitive knowledge economy increases the flow of human and social capital, developing spatial concentration of firms and high population density of people with high education levels. Conversely, this skill-based change [64] creates imbalances. Less competitive regions are challenged by brain-drain dynamics, that often depend on returning inflow of remittances [8,54]. Overall, knowledge diffusion has not been strong enough to provide better opportunities for people remaining in lagging-behind regions [50].

Figure 1.

Knowledge economies in European region, Available online: https://www.espon.eu/european-territorial-review (accessed on 23 June 2021). Source: ESPON [8].

Looking at the European context, innovation and employment growth is still concentrated in a limited number of north-western but mainly central-axis regions. There, virtuous circles of good interregional connections, a highly skilled labour force and an attractive business environment allowed neighbouring regions to benefit from their proximity. Overall, dynamic regions seem to be more adaptable to socio-economic changes and better equipped to generate employment growth [65]. In southern and eastern EU Member States, the innovation performance is weaker. Regions close to centres of innovation—mainly the capitals—do not benefit from their proximity [53]. Without place-sensitive interventions [56], which re-vitalise the socio-economic status of weaker places, we can assume that a downwards spiral will widen social, economic and political disparities between regions.

The focus on skills for the knowledge society builds a bridge between SI and the literature emphasizing the role of local contexts in skill formation and deployment [66]. The matching of individual abilities with employment requirements, as well as the signalling role of qualifications that link education with job opportunities, takes place within different regional or local skill ecosystems [67,68]. These ecosystems range from low to high skills equilibria. In research on school-to-work transitions, the internal homogeneity of transition systems has been often taken for granted. However, recent studies found relevant variations of school-to-work transition outcomes at subnational level [69]. These variations are a result of institutional determinants and contextual socio-economic conditions. A prosperous region in a favourable national context is likely to provide better labour market opportunities for young people, whilst a weak region within a weak national context is likely to produce below average outcomes. Moreover, in more internally divided countries like Italy, France, Bulgaria or Spain, regional disparities in opportunities are likely to reproduce and even increase inequalities [69].

6. Place-Sensitive Social Investment and Territorial Cohesion

As we outlined in the previous sections, local actors within multiscale governance arrangements have increasing responsibilities to promote new programs and to implement SI capacitating services [48]. In addition, contextual and territorial characteristics play a relevant role in the configuration of social risks and opportunities, exemplified by the spatial distribution of inequalities and the imbalanced diffusion of skills and innovation [9]. Virtues circles of skilled labour, economic growth and innovation in neighbouring regions are documented in north-western and central countries of the EU [8,50]. Conversely, many southern and eastern EU regions are characterised by lack of innovation, brain-drain dynamics and lack of job opportunities and high youth unemployment rates [61].

Sharp geographic divides within countries pave the risk for a fragmented and geographically uneven development. Locally based conditions can make investment policies actually effective (or ineffective), which means that deprived territories, where the positive impacts of SI services are needed the most, are also the territories in which the capacity to develop effective capacitating services are likely to be more limited. The lacking capacity stems from interactions between institutional conditions (for instance scarce availability of funds, short-sighting local elites, less efficient institutional performance) and socio-economic ones (for instance concentration of families with low income, lack of innovative firms). As an example, we observed these dynamics in Italy with the national implementation of the Youth Guarantee against youth unemployment and inactivity. The programme turned out to be less effective especially in the already highly disadvantaged Southern regions due to specific (unfavourable) institutional and socio-economic conditions ranging from largely ineffective employment services to the lack of firms investing in youth skilled labour [38].

A place-sensitive Social Investment should include territorial diversity and its consequences as a highly significant trait of the analytical frame. In terms of policy implications, this position advocates for territorialized SI strategies that rely upon locally specific socio-economic conditions and multi-scalar institutional arrangements, in order to produce win–win returns of cohesion and economic growth [2,4]. A place-sensitive and territorialised SI presents several points of contact with the debate on Territorial Cohesion. In our attempt to clarify the relationship between TC and SI, we present a review of rather concrete definitions of the concept of TC, following the stance of Abrahams [70] to look for what the TC does in concrete (urban planning) policies rather than defining it a priori, i.e., before examining similarities and differences of SI approaches.

Although TC is most often used within the spatial planning contexts, which are concerned with infrastructure and transnational cooperation, it represents an inter-disciplinary concept of socio-economic development especially within the EU. The EU special inclination for TC might even stem from its multilevel governance architecture. The Territorial Agenda 2020 indicates this in the very beginning of the document by stating that “territorial cohesion is a common goal for a more harmonious and balanced state of Europe” [71]. While the overall concept of social cohesion is a broad issue for EU institutions, TC references more concrete issues of territorial inequality leading to a divergent union. Moreover, addressing TC implies a desire to change the current internal divergence. The debate on territorial cohesion and spatial inequality recognized that regional inequalities have a strong influence on individuals’ opportunities [56,72]. Consequently, strengthening economic and social cohesion by reducing disparities between regions is a clear objective of EU policies [36,73]. As part of this objective, TC is about ensuring that people are able to mobilize the inherent features of the areas in which they live to achieve goals of socio-economic sustainability and social justice. No European citizen should be disadvantaged in terms of access to public services, housing, or employment opportunities simply by living in one region rather than another according to this view. Still, there is not a coherent definition of TC even within the most important EU documents [7,71,74]. Accordingly, adaptation processes of the concept into planning strategies on national and subnational levels differ [75].

For Humer [76], territorial cohesion refers to the territorialised provision of Services of General Interest (SGI). In this view, equal access to SGIs and particularly infrastructure is crucial for a balanced economic and social resource distribution. Apart from such planning perspectives, the connection between TC and spatial justice is also apparent in EU documents [67,71]. These documents offer descriptions of social justice within TC that present social justice almost as a mean to achieve greater cohesion within the EU. Investigating regional development documents on TC in the case of Portugal, Marques et al. filtered the most relevant EU documents on the topic and came up with four dimensions of territorial cohesion [75]. For the ESPON KITCASP [9] project, the aim was to point out policy indicators for measuring TC. For this work, the project identified four policy themes that are relevant to spatial planning and TC. Medeiros [36], on the other hand, suggested a comprehensive definition due to the relevance the TC gained in the EU cohesion policy, containing four dimensions (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Definitions of Territorial Cohesion.

A territorialised SI approach has several similarities with the concepts of TC, particularly in the way territorialised SI emphasizes inclusion (cohesion) and competitiveness (balanced and polycentric development), as well as the importance of complementarities resulting from multi-scalar interaction of public and private actors (vertical + horizontal coordination). In this view, literature on TC suggests that an integrated approach is needed in order to achieve a balanced and sustainable development—both in socio-economic and ecological terms [36,73,77,78,79]. This implies better coordination between sectoral policies at horizontal as well vertical levels [75]. A place-sensitive SI strategy can contribute to such an integrated approach as well as increase coordination between sectoral policies (even across nation state boundaries).

TC and SI meet in the attempt of strengthening economic competitiveness while simultaneously increasing individual well-being. For SI economic competitiveness and increased participation on labour markets is clearly a way to sustain welfare services. For TC this is more implicit in the goals of polycentric and balanced development, the utilization of existing territorial assets, as well as in the goal for improved access to SGIs (e.g., early childhood education and care, education facilities, etc.). Successfully implementing these goals boosts local economies, lifting lacking regions up and equipping these territories and their residents with means to navigate economic markets in a sustainable manner.

However, the two concepts differ in their analytical levels: Where SI focuses on individual life courses and well-being, looking at the policies to increase opportunities for individuals, TC targets spatial units, regions and their collective (socio-economic) development, looking at infrastructure and resource distribution to improve balanced socio-economic development. Still, the two ideas meet again in the understanding of thriving for sustainability and more (spatial) equality in socio-economic development.

Territorialising SI means to incorporate institutional specificities, as well as territorial assets to better match stocks, flows and buffers of welfare/socio-economic policies. In other words, combining TC and SI means to look at multilevel governance arrangements and territorial specificities for implementing effective and sustainable policies. Benefitting individuals at first, in turn, SI will affect collective regional socio-economic development. Therefore, the SI approach is complementary to the more infrastructure-focused TC regional planning concept. Conversely, the SI approach benefits from the TC lenses of regional specifics and, more importantly, the focus on balancing socio-economic development by including a sensibility for regional disparities.

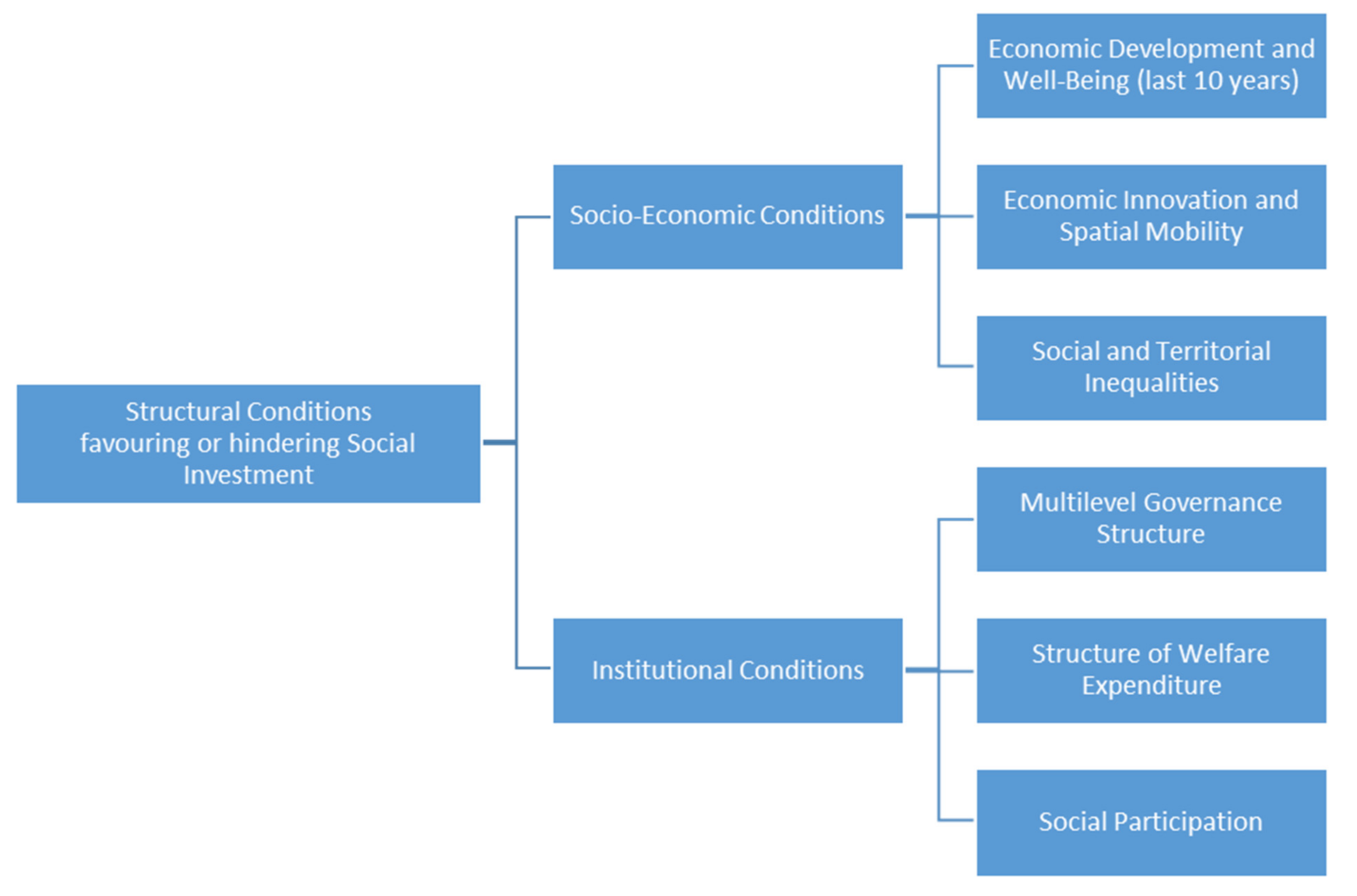

To pave the field for empirical investigations of local conditions under the concepts of SI and TC in (subnational/regional) contexts, we propose a tree of dimensions (Figure 2) that grasps not only current policy performances, but also contextual socio-economic and institutional conditions. In the direction advocated by Zaucha and Böhme [80], this is just a first step towards future and more systematic evidence-based explorations of the connections between place-sensitive SI and TC.

Figure 2.

Draft framework on SI and TC connections for the identification of indicators. Source: Own elaboration.

7. Conclusions

This paper advocates for including the territorial dimension within the analytical frame of SI by bringing more complexity into the SI approach, which is usually theorized and discussed at the national level. Combining TC with SI approaches can help mitigate territorial disparities by enabling this perspective to be effective also in adverse or highly specific local contexts. In light of the ongoing process of rescaling and territorialisation of social policies at the subnational level [47], and of persisting regional and local disparities [53], local welfare arrangements gain increasing relevance as welfare sustainability, spatial disparities and concentration of skills harden. Therefore, the success of a comprehensive SI strategy lies upon locally specific contextual conditions and multi-scalar institutional arrangements establishing complementarities among stocks, flows and buffers in social policy design. The creation of virtuous circles helps to produce the win-win returns promised by SI in terms of social cohesion and economic growth [2]. Hence, local specificities within multilevel governance structures should be considered in the frame of Social Investment research and interventions, by assuming a context- and place-sensitive approach. In fact, territories represent the place where institutional and contextual features interact, giving rise to different outcomes in terms of economic growth and social cohesion. From a policy perspective, a context-sensitive SI approach aims at promoting sustainable and inclusive growth across different contexts, avoiding the reproduction of existing inequality structures through one-size-fits all policy solutions.

On this basis, we explored the relationship between SI and TC. We maintain that a territorialised SI presents several similarities with the concepts of TC, because of the emphasis put on inclusion (cohesion) and competitiveness (balanced and polycentric development), as well as the multi-scalar interaction of public and private actors (vertical and horizontal coordination). Research on TC suggests the need of an integrated approach to pursue a balanced and sustainable development; this requires improved coordination between sectoral policies at horizontal as well vertical levels [73]. A place-sensitive SI strategy can contribute to such an integrated approach and help increase coordination between measures and policy fields. Notwithstanding analytical differences, TC and SI meet in the attempt of strengthening economic competitiveness while simultaneously increasing social inclusion and individual well-being. In the SI approach, economic competitiveness and increased participation on labour markets should pave the way for sustainable welfare states and social policies. Under the lens of TC, the connection between economics and social is more implicit in the goals of polycentric and balanced development as well as the utilization of existing territorial assets. By exploring the relationship between the territorial dimension of SI and the debate on TC, we lay a bridge that may have strong potential implications on future research on the European tools for sustainable territorial development, social integration and equality. In terms of policy implication, this crucial link between SI and TC could go a long way towards mitigating regional and spatial disparities, thus contributing to sustainable territorial development in European territories and in the European Community. Place-sensitive SI policies would help in avoiding pernicious unintended Matthew Effects that could increase inequalities and exacerbate social discontent in declining and lagging-behind areas [81]. Instead, a stronger attention to the territorial dimension of SI in designing and implementing social policies constitutes a pre-condition for successful application of measures aimed at promoting training and lifelong learning and activating and capacitating services, whose impact relies on the interaction with specific regional and local contexts [4].

Author Contributions

The three authors contributed equally to the present paper. Each phase of the paper development was discussed and worked on by all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research for this paper and the APC were funded by the HORIZON2020 project “COHSMO: Inequality, Urbanization and Territorial Cohesion: developing the European social model of economic growth and democratic capacity, grant number 727058.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References and Note

- Morel, N.; Palier, B.; Palme, J. (Eds.) Towards a Social Investment Welfare State? Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hemerijck, A. Social Investment Uses; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, B. What use is “social investment”? J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2013, 23, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazepov, Y.; Cefalo, R. The territorial dimension of Social Investment. In Handbook of Urban Social Policy; Kazepov, Y., Cucca, R., Barberis, E., Mocca, E., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Cordini, M.; Cefalo, R.; Boczy, T. Social Investment Perspective and Its Territorial Dimension; LPS-DASTU: Milano, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades, E.A. Literature reviews. Volta Rev. 2011, 111, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Towards Social Investment for Growth and Cohesion; COM (2013) 83 final; European Commission: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2013; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A52013DC0083 (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- ESPON European Territorial Review-Territorial Cooperation for the Future of Europe. ESPON EGTC: Luxembourg, 2017. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/european-territorial-review (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- ESPON. Inner Peripheries: National Territories Facing Challenges of Access to Basic Services of General Interest; ESPON: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Demeterova, B.; Fischer, T.; Schmude, J. The Right to Not Catch Up—Transitioning European Territorial Cohesion towards Spatial Justice for Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R.; Pacchi, C. In search of territorial cohesion: An elusive and imagined notion. Soc. Incl. 2020, 8, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esping-Andersen, G.; Gallie, D.; Hemerijck, A.; Myles, J. Why We Need a New Welfare State; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Third Way: The Renewal of Social Democracy; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hemerijck, A.; Burgoon, B.; Di Pietro, A.; Vydra, S. Assessing Social Investment Synergies (ASIS); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; Available online: https://iefp.eapn.pt/docs/Avaliar-as-sinergias-de-investimento-social.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Bouget, D.; Frazer, H.; Marlier, E.; Sabato, S.; Vanherecke, B. Social Investment in Europe: A Study of National Policies; ESPN: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dräbing, V.; Nelson, M. Addressing Human capital Risks and the Role of Institutional Complementarities. In Social Investment Uses; Hemerijck, A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 128–139. [Google Scholar]

- Ranci, C. (Ed.) Social Vulnerability in Europe. The New Configuration of Social Risks; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cefalo, R.; Kazepov, Y. Investing over the life course: The role of lifelong learning in a social investment strategy. Stud. Educ. Adults 2018, 50, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Porte, C.; Jacobsson, K. Social investment or recommodification? Assessing the employment policies of the EU member states. In Towards a Social Investment Welfare State; Morel, N., Palier, B., Palme, J., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2011; pp. 117–149. [Google Scholar]

- Lundvall, B.; Lorenz, E. Social investment in the globalising learning economy—A European perspective. In Towards a Social Investment Welfare State; Morel, N., Palier, B., Palme, J., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2012; pp. 235–259. [Google Scholar]

- Cantillon, B.; Van Lancker, W. Three Shortcomings of the Social Investment Perspective. Soc. Policy Soc. 2013, 12, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.; Stephens, J.D. Do social investment policies produce more and better jobs? In Towards a Social Investment Welfare State? Ideas, Policies and Challenges; Morel, N., Palier, B., Palme, J., Eds.; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- León, M.; Pavolini, E. ‘Social Investment’ or Back to ‘Familism’: The Impact of the Economic Crisis on Family and Care Policies in Italy and Spain. South Eur. Soc. Politics 2014, 19, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K.J. Promoting social investment through work-family policies: Which nations do it and why? In Towards a Social Investment Welfare State; Morel, N., Palier, B., Palme, J., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2012; pp. 153–180. [Google Scholar]

- Cronert, A.; Palme, J. Social Investment at Crossroads “The Third Way” or “The Enlightened Path” Forward? In Decent Incomes for All: Improving Policies in Europe; Cantillon, B., Goedemé, T., Hills, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Garritzmann, J.L.; Häusermann, S.; Palier, B.; Zollinger, C. WoPSI—The World Politics of Social Investment. An International Research Project to Explain Variance in Social Investment Agendas and Social Investment Reforms across Countries and World Regions; LIEPP: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Solga, H. Education, economic inequality and the promises of the social investment state. Socio-Econ. Rev. 2014, 12, 269–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraceno, C. A Critical Look to the Social Investment Approach from a Gender Perspective. Soc. Politics 2015, 22, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonoli, G.; Cantillon, B.; Van Lancker, W. Social investment and the Matthew effect: Limits to a strategy In Social Investment Uses; Hemerijck, A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Checchi, D.; van de Werfhorst, H.; Braga, M.; Meschi, E. The Policy Response: Education. Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts. In Changing Inequalities in Rich Countries: Analytical and Comparative Perspectives; Nolan, B., Salverda, W., Checchi, D., Marx, I., McKnight, A., Tóth, I.G., van de Werfhorst, H.G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 294–317. [Google Scholar]

- Di Stasio, V.; Solga, H. Education as social policy: An introduction. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2017, 27, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatinelli, S.; Semprebon, M. The vertical division of responsibility for social services within and beyond the State: Issues in empowerment, participation and territorial cohesion. In Social Services Disrupted. Changes, Challenges and Policy Implications for Europe in Times of Austerity; Martinelli, F., Anttonen, A., Matzke, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 114–133. [Google Scholar]

- Verbist, G.; Matsaganis, M. The Redistributive Capacity of Services in the EU. For Better for Worse, for Richer for Poorer. Labour Market Participation, Social Redistribution and Income Poverty in the EU; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abrassart, A.; Bonoli, G. Availability, Cost or Culture? Obstacles to childcare services for low income families. J. Soc. Policy 2015, 44, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vliet, O.; Wang, C. Social Investment and Poverty Reduction: A Comparative Analysis across Fifteen European Countries. J. Soc. Policy 2015, 44, 611–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, E. Territorial Cohesion: An EU concept. Eur. J. Spat. Dev. 2016, 60, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kazepov, Y.; Ranci, C. Making Social Investment Work: A Comparative Analysis of the Socio-Economic Preconditions of Social Investment Policies; SISEC Conference: Milan, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cefalo, R.; Boczy, T.; Kazepov, Y.; Arlotti, M.; Cordini, M.; Parma, A.; Ranci, C.; Sabatinelli, S. COHSMO Project Report on Literature Review on Social Investment. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kenworthy, L. Enabling Social Policy. In Social Investment Uses; Hemerijck, A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli, F.; Anttonen, A.; Matzke, M. (Eds.) Social Services Disrupted; Changes, Challenges and Policy Implications for Europe in Times of Austerity; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, Northampton, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti, A.; Mingione, E.; Polizzi, E. Local Welfare Systems. A Challenge for Social Cohesion. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 1925–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F. (Ed.) The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research; Edward Elgar: Aldershot, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kazepov, Y.; Barberis, E. The territorial dimension of social policies and the new role of cities. In Handbook of European Social Policy; Patricia, K., Noemi, L.-B., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton MA, USA, 2017; pp. 302–318. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, S.; Bassi, A.; Csoba, J.; Sipos, F. (Eds.) Innovative Social Investment; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell, M.; Brown, J. Against the local trap: Scale and the study of environment and development, Progress. Dev. Stud. 2005, 5, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatinelli, S. Aspetti critici dell’innovazione sociale nel contesto italiano. Prospett. Soc. E Sanit. 2015, XLV, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kazepov, Y. (Ed.) Rescaling Social Policies: Towards Multilevel Governance in Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ranci, C.; Brandsen, T.; Sabatinelli, S. Social Vulnerability in European Cities. In The Role of Local Welfare in Times of Crisis; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kröger, S. Five Years down the Road. An Evaluation of the Streamlining of the Open Method of Coordination in the Social Policy Field; OSE Briefing Paper; The European Social Observatory: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Iammarino, S.; Rodriguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M. Regional inequality in Europe. Evidence, theory and policy implications. J. Econ. Geogr. 2018, 53, 898–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marelli, E.; Patuelli, R.; Signorelli, M. Regional unemployment in the EU before and after the global crisis. Post-Communist Econ. 2012, 24, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, N.; Dijkstra, L.; Lapuente, V. Mapping the Regional Divide in Europe. A Measure for Assessing Quality of Government in 206 European Regions. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 122, 315–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, L. My Region, My Europe, Our Future. Seventh Report on Economic, Social and Territorial Cohesion; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cefalo, R.; Scandurra, R.; Kazepov, Y. Youth Labor Market Integration in European Regions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.; Cantillon, B.; Marlier, B.; Nolan, B. Social Indicators: The EU and Social Inclusion; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, F. An Agenda for a Reformed Cohesion Policy; Independent Report Prepared at the Request of Danuta Hübner, Commissioner for Regional Policy; European Communities: Bruxells, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, F.; McCann, P.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. The case for regional development intervention: Place-based versus place-neutral approaches. J. Reg. Sci. 2012, 52, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatinelli, S. Politiche per Crescere. In La Prima Infanzia tra Cura e Investimento Sociale; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lundvall, B. The Learning Economy and the Economics of Hope; Anthem Press: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wren, A. Social investment and the Service Economy Trilemma. In Social Investment Uses; Hemerijck, A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Storper, M. Separate Worlds? Explaining the current wave of regional economic polarization. J. Econ. Geogr. 2018, 18, 247–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, E.; van der Zwet, A. Sustainable and Integrated Urban Planning and Governance in Metropolitan and Medium-Sized Cities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, A.L. Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 74, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, E.; Bound, J.; Machin, S. Implications of skill-biased technological change: International evidence. Q. J. Econ. 1998, 113, 1245–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratesi, U.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. The crisis and regional employment in Europe: What role for sheltered economies? CAMRES 2016, 9, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finegold, D. Creating self-sustaining, high-skill ecosystems. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 1999, 15, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalziel, P. Regional skill ecosystems to assist young people making education employment linkages in transition from school to work. Local Econ. 2015, 30, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED)—Designing Local Skills Strategies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Scandurra, R.; Cefalo, R.; Kazepov, Y. School to work outcomes during the Great Recession, is the regional scale relevant for young people’s life chances? J. Youth Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, G. What “Is” Territorial Cohesion? What Does It “Do”? Essentialist Versus Pragmatic Approaches to Using Concepts. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2013, 22, 2134–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Territorial Agenda of the European Union 2020: Towards an Inclusive, Smart and Sustainable Europe of Diverse Regions. Agreed at the Informal Ministerial Meeting of Ministers Responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development; European Commission: Bruxells, Belgium, 2011; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/communications/2011/territorial-agenda-of-the-european-union-2020 (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Böhme, K.; Doucet, P.; Komornicki, T.; Zaucha, J.; Świątek, D. How to Strengthen the Territorial Dimension of ‘Europe 2020’ and EU Cohesion Policy; Report Based on the Territorial Agenda 2020; Polish Presidency of the Council of the European Union: Warsaw, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Faludi, A. Territorial Cohesion and Subsidiarity under the European Union Treaties: A Critique of the ‘Territorialism’ Underlying. Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 1594–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion. Turning Territorial Diversity into Strength; European Commission: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2008; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/communications/2008/green-paper-on-territorial-cohesion-turning-territorial-diversity-into-strength, (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Marques, T.S.; Saraiva, M.; Santinha, G.; Guerra, P. Re-Thinking Territorial Cohesion in the European Planning Context. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2018, 42, 547–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humer, A. Researching social services of general interest: An analytical framework derived from underlying policy systems. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2013, 21, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, E.; Rauhut, D. Territorial Cohesion Cities: A policy recipe for achieving Territorial Cohesion? Reg. Stud. 2018, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, G.; Gonzalez, A.; Gleeson, J.; McCarthy, E.; Adams, N.; Pinch, P.; KITCASP. Key Indicators for Territorial Cohesion and Spatial Planning; Final Report Part D Appendix, B.; ESPON & National University of Ireland: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dao, H.; Plagnat Cantoreggi, P.; Rousseaux, V. Operationalizing a con-tested concept. Indicators of territorial cohesion. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 638–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaucha, J.; Böhme, K. Measuring territorial cohesion is not a mission impossible. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 627–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2018, 11, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).