The Human Capital for Value Creation and Social Impact: The Interpretation of the IR’s HC Definition

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- alignment with and support for an organization’s governance framework, risk management approach, and ethical values →

- -

- ability to understand, develop and implement an organization’s strategy →

- -

- loyalties and motivations for improving processes, goods and services, including their ability to lead, manage and collaborate’. This definition is closely linked to value creation [18], goes beyond economic performance, and is an extensive and wide concept involving different scales also external to the organizations.

- RQ1: Is the IR’s HC definition effective and applicable to both conventional companies (including SMEs) and social cooperatives?

- RQ2: Are the components of the IR’s HC definition useful to articulate a clear picture of the value generated by the HC management of conventional companies (including SMEs) and social cooperatives?

- RQ3: Could the IR be a possible and useful driving force to improve the HC valorization within both conventional companies (including SMEs) and social cooperatives towards the goal of improving social impact?

2. Materials and Methods

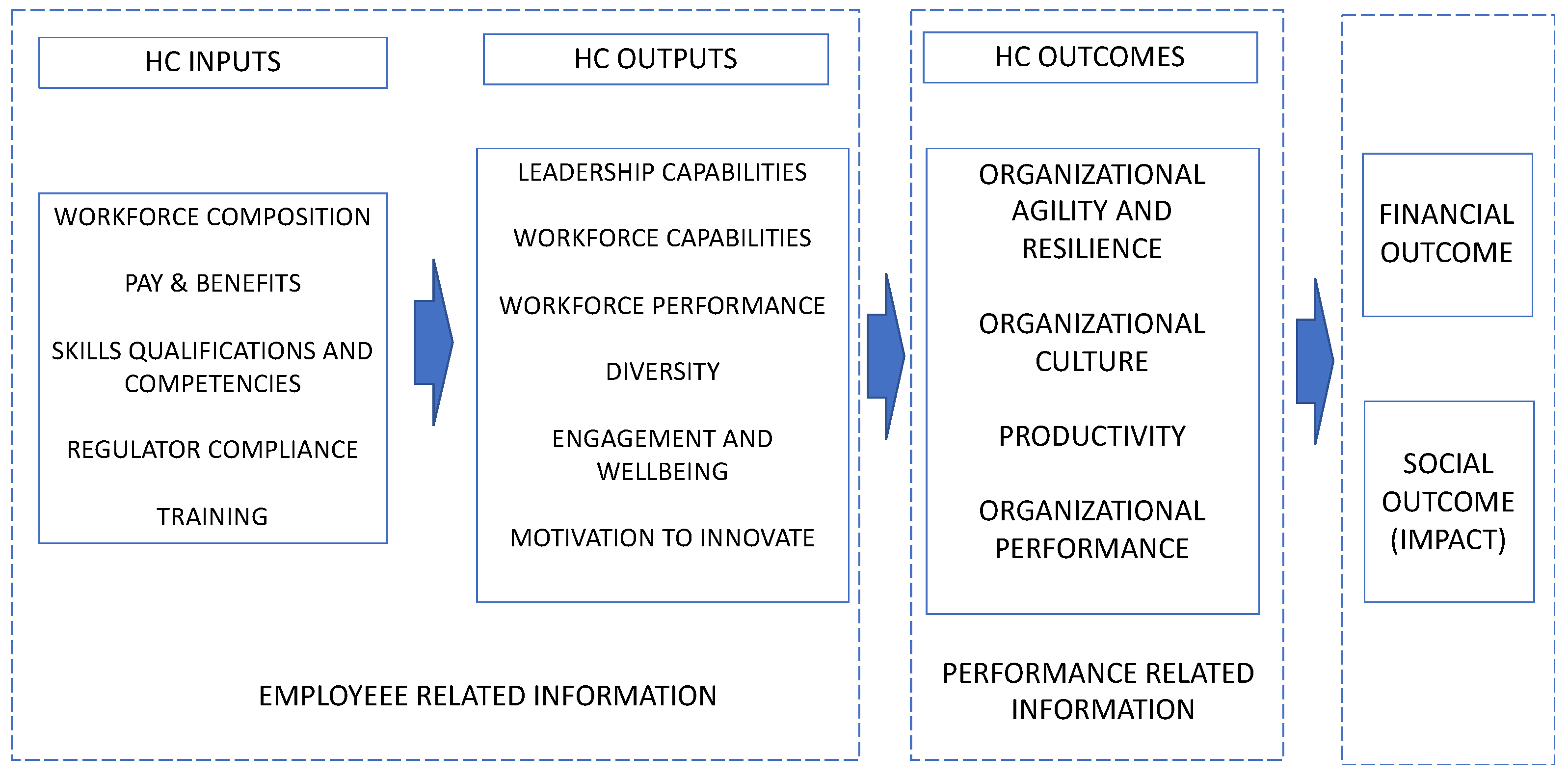

- (1)

- workforce-related factors (human capital), such as the workforce’s capabilities, its motivation, and commitment;

- (2)

- company-internal factors (structural capital) include a company’s operational performance, its innovation ability, as well as its corporate culture;

- (3)

- company-external factors (relational capital), parameters outside the company that are relevant to a company’s success.

3. Results

- Knowledge and use of the human capital concept,

- HC and social value creation,

- Value creation through HC between conventional firms and social cooperatives.

3.1. Knowledge and Use of the Human Capital Concept

- (1)

- on the one hand, those who see the HC as a physical resource of the company, a “fuel that makes it go”, from a perspective mainly oriented to the interest and the point of view of the company;

- (2)

- then, some look primarily at the more “intangible” components of the HC, those related to the skills inherent or developed by employees primarily on a personal and individual level, and not only and solely in the workplace or the formative framework.

- (1)

- employee involvement, staff satisfaction rate, motivation, commitment;

- (2)

- corruption, business ethics, respect for human rights;

- (3)

- diversity of staff, gender equality;

- (4)

- experience, training, education;

- (5)

- average age/professional seniority/qualifications, education;

- (6)

- productivity;

- (7)

- turnover, staff loyalty/commitment rate.

3.2. HC and Social Value Creation

3.3. Value Creation through HC between Conventional Firms and Social Cooperatives

- -

- a quite hidden acknowledgment and awareness of the generated social impact;

- -

- a quite general lack of shared and effective quantitative metrics to measure and assess the related social impact;

- -

- a general impression that the external social impact of the organization may, in some cases, appear more easily catchable/caught than the internal social impact.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- recognizing that HC is an asset for the company (i.e., all respondents speak about HC but no one looks at it as capital, preferring the use of other concepts such as value, skill, etc.);

- (2)

- evaluating the stock of HC based on personal skills, education-training-attitudes (a phase that normally occurs during the staff selection and hiring);

- (3)

- acting in order to implement policies aimed at HC stock growth in order to improve the company’s performance (in practice, it seems that some larger companies make this operational effort more evident/concrete than others);

- (4)

- assessing the results/impacts of the company actions and policies in terms of increasing the individual sub-components of the HC definition. This is a phase very rarely carried out by organizations, primarily for reasons of excessive complexity and difficulty in measuring intangibles or partly also due to a mismatch between costs and benefits. Further investigations are needed to provide a more complete picture of such critical points.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Appendix A

- BRIEF INTRO WITH OBJECTIVES AND PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS OF THE RESEARCH: Focus on the non-monetary value of “human capital” in order to reach a common/shared model but also adapted to the needs of social cooperatives to improve personnel management, decrease turnover, enhance the role of conventional enterprises and social cooperatives in the creation of value for society, and social impact through the enhancement of the HC.

- PRELIMINARY INFO

- Company/cooperative name

- Typology

- Position held

- Years of seniority in the company

- Number of employees

- HC AND INTEGRATED REPORT

- 1.

- Do you use the term “human capital” (HC) in your organization?

- yes (1)

- no (2)

- in part (3)

- 2.

- If you don’t use it, why?

- 3.

- Alternatively, which term do you prefer to use?

- 4.

- Based on your experience, could you give us a personal definition of “human capital” (HC)?

- 5.

- For your work, have you ever heard of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) or Integrated Reporting (IR)?

- yes (1)

- no (2)

- in part (3)

- 6.

- The IR defines HC as “People’s competencies, capabilities and experience, and their motivations to innovate, including their:

- -

- Alignment with and support for an organization’s governance framework, risk management approach, and ethical values

- -

- Ability to understand, develop and implement an organization’s strategy

- -

- Loyalties and motivations for improving processes, goods and services, including their ability to lead, manage and collaborate “.

What do you think of this definition? Do you find it suitable for your organization? - 7.

- Based on this definition of HC, in your opinion what are the best indicators to measure/evaluate the impact of HC on the creation of value for your organization (in order: 1 = most important, 7 = least important)?

- ______ employee involvement/staff satisfaction rate/motivation/commitment

- ______ corruption/business ethics/respect for human rights

- ______ staff diversity/gender equality

- ______ average age/seniority/qualifications/education

- ______ productivity

- ______ experience/training/education

- ______ staff turnover/retention rate

- 8.

- In your company/cooperative, the social report or another form of a non-financial report:

- is required

- you prepare it even if it is not mandatory

- if you do, which standard do you use?

- 9.

- In your opinion, why is it (or not) important to prepare a non-financial report?

- 10.

- If you prepare it, what is the most difficult aspect to measure/value/tell when you talk about your HC?

- Measure/evaluate

- Valuing/telling

- HC AND SOCIAL IMPACT

- 11.

- If you refer to the “social capital” of your organization, what comes to your mind?

- 12.

- How does the human capital of your company/cooperative influence its social impact?

- 13.

- How could the connection between HC and the social impact of your company/cooperative be measured?

- HC BETWEEN NO PROFIT AND PROFIT

- 14.

- In your opinion, what are the main differences of HC between profit and non-profit?

- 15.

- Please indicate a positive aspect of the profit sector that should be co-opted for the management and enhancement of HC in the not-for-profit/world of social cooperatives.

- 16.

- Indicate a negative aspect of the profit sector in your opinion that should be avoided or in which the not-for-profit can instead set a good example for imitation.

- 17.

- In your opinion, is the social impact generated by the not-for-profit sector greater/lesser/equal to that of the profit sector, or it is not possible to answer this?

- 18.

- How can the world of research/university help you to improve your work of valorization, measurement, description of the HC?

References

- Cheng, M.; Green, W.; Conradie, P.; Konishi, N.; Romi, A. The International Integrated Reporting Framework: Key Issues and Future Research Opportunities. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2014, 25, 90–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, J.; Dai, T. Integrated thinking as a cultural control? Meditari Account. Res. 2017, 25, 574–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Brown, J.; Frame, B.; Thomson, I. Theorizing engagement: The potential of a critical dialogic approach. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2007, 20, 356–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modell, S. Making institutional accounting research critical: Dead end or new beginning? Account. Audit. Account. J. 2015, 28, 773–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R. Taking a Long View on What We Now Know About Social and Environmental Accountability and Reporting. Issues Soc. Environ. Account. 2007, 1, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Gray, S. Accountability and human rights: A tentative exploration and a commentary. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2011, 22, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Bebbington, J.; Collison, D. NGOs, civil society and accountability: Making the people accountable to capital. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2006, 19, 319–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreaus, M.; Costa, E. Toward an Integrated Accountability Model for Nonprofit Organizations. In Advances in Public Interest Accounting; Costa, E., Parker, L.D., Andreaus, M., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014; pp. 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Molloy, J.C.; Chadwick, C.; Ployhart, R.E.; Golden, S.J. Making Intangibles “Tangible” in Tests of Resource-Based Theory: A Multidisciplinary Construct Validation Approach. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1496–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitolla, F.; Raimo, N. Adoption of Integrated Reporting: Reasons and Benefits—A Case Study Analysis. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 13, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camodeca, R.; Almici, A.; Sagliaschi, U. Strategic information disclosure, integrated reporting and the role of intellectual capital. J. Intellect. Cap. 2019, 20, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes-Rossi, F.; Nicolò, G.; Tudor, A.T.; Zanellato, G. Drivers of integrated reporting by state-owned enterprises in Europe: A longitudinal analysis. Meditari Account. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Baldo, M. The implementation of integrating reporting in SMEs: Insights from a pioneering experience in Italy. Meditari Account. Res. 2017, 25, 505–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Baldo, M. Is It Time for Integrated Reporting in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises? Reflections on an Italian Experience. In Corporate Social Responsibility and Governance; Idowu, S.O., Frederiksen, C.S., Mermod, A.Y., Nielsen, M.E.J., Eds.; CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 183–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Krzus, M.P.; Ribot, S. Meaning and Momentum in the Integrated Reporting Movement. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2015, 27, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, L.; Unerman, J.; de Villiers, C. Evaluating the integrated reporting journey: Insights, gaps and agendas for future research. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 1294–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paternostro, S. Integrated Reporting and Social Disclosure: True Love or Forced Marriage? A Multidimensional Analysis of a Contested Concept. In Studies in Managerial and Financial Accounting; Songini, L., Pistoni, A., Baret, P., Kunc, M.H., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2020; pp. 107–146. [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers, C.; Hsiao, P.-C.K.; Maroun, W. Developing a conceptual model of influences around integrated reporting, new insights and directions for future research. Meditari Account. Res. 2017, 25, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Lapiedra, R.; Marco-Fondevila, M.; Scarpellini, S.; Llena-Macarulla, F. Measurement of the Human Capital Applied to the Business Eco-Innovation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, V.; Demartini, C.; Trucco, S. Does environmental, social and governance performance influence intellectual capital disclosure tone in integrated reporting? J. Intellect. Cap. 2019, 20, 100–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarik, M.S.; Chandran, V.G.R.; Devadason, E.S. Measuring Human Capital in Small and Medium Manufacturing Enterprises: What Matters? Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 137, 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antadze, N.; Westley, F.R. Impact Metrics for Social Innovation: Barriers or Bridges to Radical Change? J. Soc. Entrep. 2012, 3, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.; Ramus, T.; Andreaus, M. Accountability as a Managerial Tool in Non-Profit Organizations: Evidence from Italian CSVs. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2011, 22, 470–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Dillard, J. Integrated reporting: On the need for broadening out and opening up. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2014, 27, 1120–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, L.; Morgan, G.G.; Cordery, C.J. Accountability and not-for-profit organisations: Implications for developing international financial reporting standards. Financ. Account. Manag. 2018, 34, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L. Multifaceted not-for-profit accountability: Its measurement, cultural context, and impact on perceived social performance. Financ. Account. Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejedo-Romero, F.; Araujo, J.F.F.E. The influence of corporate governance characteristics on human capital disclosure: The moderating role of managerial ownership. J. Intellect. Cap. 2022, 23, 342–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secundo, G.; Elena Perez, S.; Martinaitis, Ž.; Leitner, K.H. An Intellectual Capital framework to measure universities’ third mission activities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 123, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, J.; Bernardi, C.; Guthrie, J.; Demartini, P. Integrated reporting: A structured literature review. Account. Forum 2016, 40, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuozzo, B.; Dumay, J.; Palmaccio, M.; Lombardi, R. Intellectual capital disclosure: A structured literature review. J. Intellect. Cap. 2017, 18, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, J. A critical reflection on the future of intellectual capital: From reporting to disclosure. J. Intellect. Cap. 2016, 17, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambon, S. Ten years after: The past, the present and the future of scholarly investigation on intangibles and intellectual capital (IC). J. Intellect. Cap. 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolò, G.; Aversano, N.; Sannino, G.; Tartaglia Polcini, P. ICD corporate communication and its determinants: Evidence from Italian listed companies’ websites. Meditari Account. Res. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.; Ricceri, F.; Dumay, J. Reflections and projections: A decade of Intellectual Capital Accounting Research. Br. Account. Rev. 2012, 44, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, V.; Smith, S.J. Human capital, value creation and disclosure. J. Hum. Resour. Costing Account. 2010, 14, 262–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveiby, K.E. The New Organizational Wealth: Managing & Measuring Knowledge-Based Assets, 1st ed.; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ployhart, R.E.; Nyberg, A.J.; Reilly, G.; Maltarich, M.A. Human Capital Is Dead; Long Live Human Capital Resources! J. Manag. 2014, 40, 371–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysekera, I.; Guthrie, J. An empirical investigation of annual reporting trends of intellectual capital in Sri Lanka. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2005, 16, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Go, S. Human Capital and Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadamin, H.H.; Atan, T. The Impact of Strategic Human Resource Management Practices on Competitive Advantage Sustainability: The Mediation of Human Capital Development and Employee Commitment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bini, L.; Dainelli, F.; Giunta, F. Business model disclosure in the Strategic Report: Entangling intellectual capital in value creation process. J. Intellect. Cap. 2016, 17, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilling, P.F.A.; Caykoylu, S. Determinants of Companies that Disclose High-Quality Integrated Reports. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terblanche, W.; De Villiers, C. The influence of integrated reporting and internationalisation on intellectual capital disclosures. J. Intellect. Cap. 2019, 20, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passetti, E.; Cinquini, L. A Comparative Analysis of Human Capital Disclosure in Annual Reports and Sustainability Reports. In Value Creation, Reporting, and Signaling for Human Capital and Human Assets; Russ, M., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan US: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 213–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, J. The International Integrated Reporting Council: A story of failure. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2015, 27, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, J.; Bernardi, C.; Guthrie, J.; La Torre, M. Barriers to implementing the International Integrated Reporting Framework: A contemporary academic perspective. Meditari Account. Res. 2017, 25, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomasson, A. Exploring the ambiguity of hybrid organisations: A stakeholder approach. Financ. Account. Manag. 2009, 25, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornforth, C. Chapter 13: The Governance of Hybrid Organisations. Handbook on Hybrid Organisations; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 220–236. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim, A.; Battilana, J.; Mair, J. The governance of social enterprises: Mission drift and accountability challenges in hybrid organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 2014, 34, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.-E.; Vakkuri, J. Governing Hybrid Organisations; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Augusto Felício, J.; Couto, E.; Caiado, J. Human capital, social capital and organizational performance. Manag. Decis. 2014, 52, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamerschlag, R.; Moeller, K. The Positive Effects of Human Capital Reporting. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2011, 14, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanda, G.; Lacchini, M.; Oricchio, G. La Valutazione del Capitale Umano Nell’impresa: Modelli Qualitativi e Quantitativi di Logica Economico-Aziendale; G. Giappichelli: Torino, Italy, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, S.Q.; Dumay, J. The qualitative research interview. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2011, 8, 238–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; Applied social research methods series; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, B.; Scapens, R.W.; Theobald, M. Research Method and Methodology in Finance and Accounting, 2nd ed.; South-Western, Cengage Learning: Andover, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Galletta, A.; Cross, W.E. Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and Beyond: From Research Design to Analysis and Publication; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kenno, S.A.; McCracken, S.A.; Salterio, S.E. Financial Reporting Interview-Based Research: A Field Research Primer with an Illustrative Example. Behav. Res. Account. 2017, 29, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.J.; Johnston, M.; Robertson, C.; Glidewell, L.; Entwistle, V.; Eccles, M.P.; Grimshaw, J.M. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol. Health 2010, 25, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luborsky, M.R.; Rubinstein, R.L. Sampling in Qualitative Research: Rationale, Issues, and Methods. Res. Aging 1995, 17, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, M.N. Sampling for qualitative research. Fam. Pract. 1996, 13, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benevene, P.; Cortini, M. Interaction between structural capital and human capital in Italian NPOs: Leadership, organizational culture and human resource management. J. Intellect. Cap. 2010, 11, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W.; Higgins, C. Integrated Reporting and internal mechanisms of change. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2014, 27, 1068–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, A.; Littig, B.; Menz, W. Introduction: Expert Interviews—An Introduction to a New Methodological Debate. In Interviewing Experts; Bogner, A., Littig, B., Menz, W., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2009; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S. Towards a social theory of the firm: Worker cooperatives reconsidered. J. Coop. Organ. Manag. 2015, 3, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, F.; Chapelle, K.; Prouteau, L. Wage differentials between conventional firms and non-worker cooperatives: Analysis of evidence from France. Compet. Chang. 2017, 21, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, K.; Schaltegger, S.; Crutzen, N. Advancing the integration of corporate sustainability measurement, management and reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 859–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.; Parker, L.D.; Andreaus, M. The Rise of Social and Non-Profit Organizations and their Relevance for Social Accounting Studies. In Advances in Public Interest Accounting; Costa, E., Parker, L.D., Andreaus, M., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dillard, J.; Roslender, R. Taking pluralism seriously: Embedded moralities in management accounting and control systems. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2011, 22, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisi, M.; Alice Centrone, F.; Corazza, L. Does the Integrated Reporting’s definition of human capital fit with the HR manager’s perspective? Financ. Rep. 2020, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, V.; Prince, S.; Dixon-Fyle, S.; Yee, L. Delivering through Diversity; McKinsey & Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018; p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, A. A General Theory of Social Impact Accounting: Materiality, Uncertainty and Empowerment. J. Soc. Entrep. 2018, 9, 132–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroeger, A.; Weber, C. Developing a Conceptual Framework for Comparing Social Value Creation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 513–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Yuthas, K. Measuring and Improving Social Impacts: A Guide for Nonprofits, Companies, and Impact Investors; Greenleaf Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dumay, J.; Guthrie, J.; Farneti, F. Gri Sustainability Reporting Guidelines For Public And Third Sector Organizations: A critical review. Public Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.; Pesci, C.; Andreaus, M.; Taufer, E. Empathy, closeness, and distance in non-profit accountability. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 32, 224–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarter, J.; Richmond, B.J. Accounting for Social Value in Nonprofits and For-Profits. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2001, 12, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; Mack, J.; Tooley, S.; Irvine, H. Do Not-For-Profits Need Their Own Conceptual Framework?: A NFP Conceptual Framework? Financ. Account. Manag. 2014, 30, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussinki, H.; Kianto, A.; Vanhala, M.; Ritala, P. Happy Employees Make Happy Customers: The Role of Intellectual Capital in Supporting Sustainable Value Creation in Organizations. In Intellectual Capital Management as a Driver of Sustainability; Matos, F., Vairinhos, V., Selig, P.M., Edvinsson, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, M.-A.; Cerbone, D.; Maroun, W. Exploring the challenges of preparing an integrated report. Meditari Account. Res. 2017, 25, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.; Manes-Rossi, F.; Orelli, R.L. Integrated reporting and integrated thinking in Italian public sector organisations. Meditari Account. Res. 2017, 25, 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Dillard, J. Critical accounting and communicative action: On the limits of consensual deliberation. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2013, 24, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girella, L.; Dameri, P. Putting Integrated Reporting Where It Was Not: The Case of the Not-for-Profit Sector. Financ. Rep. 2019, 111–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girella, L.; Zambon, S.; Rossi, P. Reporting on sustainable development: A comparison of three Italian small and medium-sized enterprises. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 981–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID RESPONDENT | GENDER (M/F) | SENIORITY (Years in the Company) | INDUSTRY/SECTOR | CONVENTIONAL FIRM OR SOCIAL COOPERATIVE | N. OF EMPLOYEES | TYPE OF NFR REPORTING PROVIDED (If Any) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | M | 8 | Pharmaceutical | Conventional firm | 560 | n.a. |

| R2 | F | Taps and fitting | Conventional firm | 87 | n.a. | |

| R3 | F | Human resources | Conventional firm | 2293 | IR | |

| R4 | M | Intellectual property consultancy | Conventional firm | 100 | n.a. | |

| R5 | M | Textile | Conventional firm | 13 | n.a. | |

| R6 | F | 30 | Welfare, socio-health and educational services | Social cooperative | 743 | SOCIAL REPORT |

| R7 | F | 34 | Cleaning and Environmental Services | Social cooperative | 459 | SOCIAL REPORT |

| R8 | F | 5 | Cleaning and Environmental Services | Social cooperative | 459 | SOCIAL REPORT |

| R9 | M | 22 | Circular economy/waste collection and disposal | Social cooperative | 250 | n.a. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cisi, M.; Centrone, F.A. The Human Capital for Value Creation and Social Impact: The Interpretation of the IR’s HC Definition. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13136989

Cisi M, Centrone FA. The Human Capital for Value Creation and Social Impact: The Interpretation of the IR’s HC Definition. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):6989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13136989

Chicago/Turabian StyleCisi, Maurizio, and Francesca Alice Centrone. 2021. "The Human Capital for Value Creation and Social Impact: The Interpretation of the IR’s HC Definition" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 6989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13136989

APA StyleCisi, M., & Centrone, F. A. (2021). The Human Capital for Value Creation and Social Impact: The Interpretation of the IR’s HC Definition. Sustainability, 13(13), 6989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13136989