Leasing as an Alternative Form of Financing within Family Businesses: The Important Advisory Role of the Accountant

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Financing Decisions in Family Businesses

2.2. Alternative Forms of Financing for Family Firms: The Role of Leasing

2.3. The Importance of the External Accountant in (Financial) Decision-Making

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Analyses

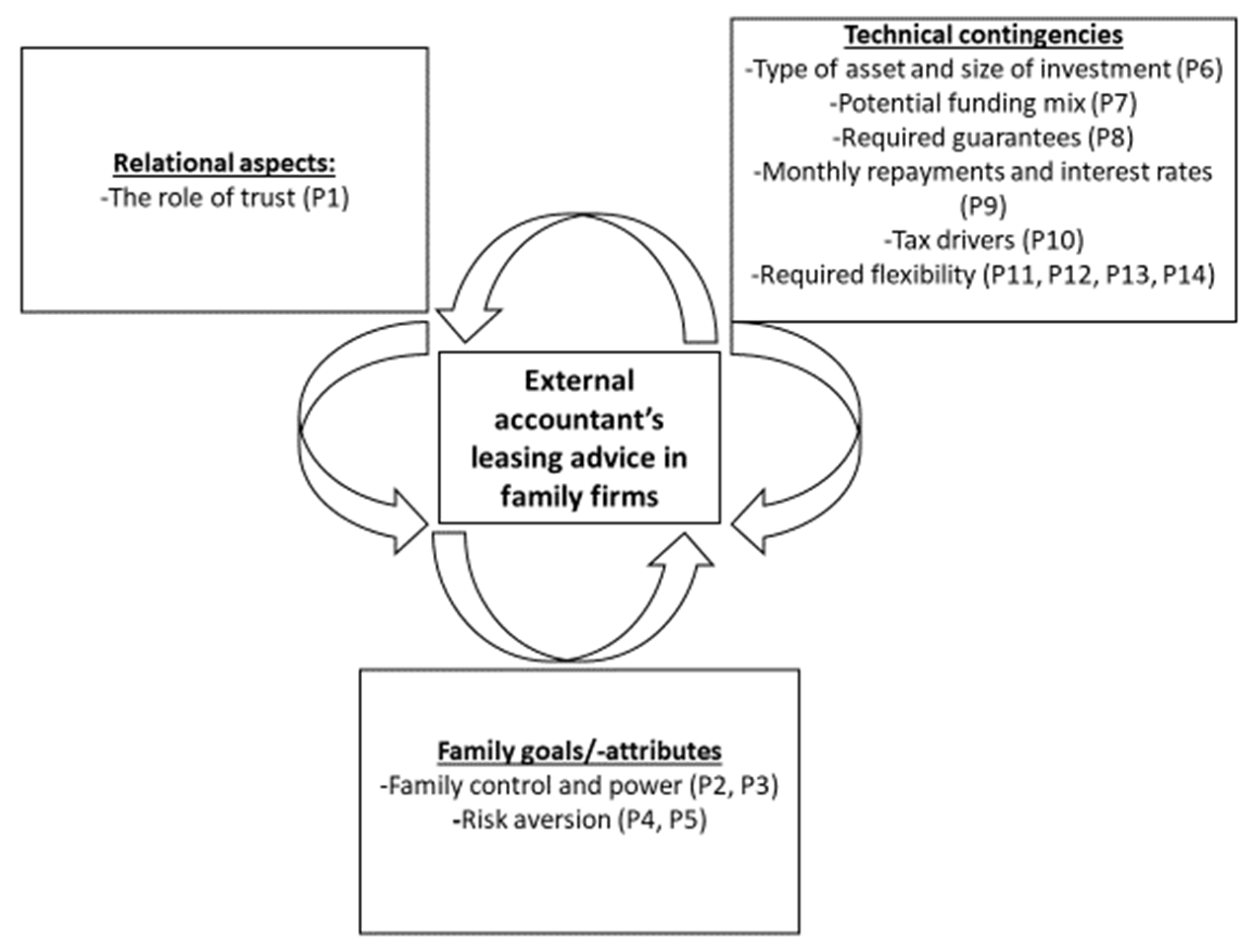

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Relational Aspects

“When we are faced with a problem of how to finance, we do advise on the best form of financing to follow. But sometimes we get the question ‘should we lease?’, ‘should we invest?’“. (A3)

“The entrepreneur says: Look, a certain amount of funding is needed for a certain purchase or we temporarily need extra money in the company”. (A5)

“It depends a bit on the relationship with the customer, but let’s say that with the majority of customers, the decision about financing the business lies with us”. (A2)

4.2. Family Goals and Attributes

4.2.1. Maintaining Control

“In family firms, I don’t think you often get financing proposals where outsiders would get control or participation rights in the firm”. (A4)

“We see more and more that the control, also in family businesses, is less and less important. Certainly, with the Covid-19 situation we currently operate in, it would sometimes be useful if other partners could say ‘I’ll buy you out and continue the business’. Because continuing to pass it on to the next generation is certainly not always evident”. (A5)

“Yes, that is being looked at, but it is not about financing. The reason for attracting an external financier would then rather be about how much power you give to such a person. Then it would be less about the financing itself”. (A3)

“The formalities are about the same, I think. If you have to give a personal guarantee to the bank, it is of course different from when you don’t have to. A separate document has to be drawn up for this and then the formality is of course greater”. (A2)

“Banks are more inclined to request interim figures than a leasing company. Leasing companies limit themselves to requesting figures once or not at all. They base themselves on what has been officially filed by the national bank. The guarantee structure is different. They remain the owner of the asset and can simply take it back. Whether this really plays a role in the assessment of the decision, no I don’t have that experience”. (A1)

4.2.2. Risk Aversion

“I know entrepreneurs who are not concerned with the risk factor; they say I need an investment and I just do it. I also have a case of a family business that is very consciously working on identifying every risk factor”. (A4)

“Low risk: that may be true because with leasing, the company’s guarantee is limited to the asset, but if you don’t pay off your financing with the bank, they can seize everything. So, in that respect the risk is higher with classic financing options”. (A1)

4.3. Technical Contingencies

4.3.1. Type of Asset and Size of the Investment

“Oftentimes, we get this question from a client: I have two proposals here, one from the car dealer and one from the bank. Then they are put next to each other”. (A2)

“This depends on the type of asset in question. If financial resources are needed, you will see generally that they mainly opt for bank financing, rather than attracting external financiers. This is a typical feature for family businesses”. (A3)

“It depends on the type of asset as well as the amount to be financed. A typical example: cars. In this case, everyone automatically looks in the direction of leasing, but when it comes to buildings or real estate, people look more to classical financing options”. (A1)

“Leasing or renting will be encountered mainly in car fleets and very occasionally in real estate”. (A3)

4.3.2. Funding Mix

“Certainly, when it comes to larger amounts, a combination of funding options is increasingly being looked at.” (A4)

“A bank comes up with a proposal and it is seen as “a sacred thing” and then of course I come and say we are going to do it this way for this reason, or I think it is better to use a bit of the entrepreneur’s own contribution or possibly a combination with financing, a combination with leasing. So, I suggest to look at different forms of financing”. (A5)

“In recent years, we have seen more and more the mixed financing phenomena, with, for example, PMV intervening or a European financing fund providing guarantees. The other things that are also coming back more and more are the ‘FFF’: family, friends, fools and win-win loans”. (A4)

4.3.3. Required Guarantees

“Definitely look at the guarantee. If, for example, you or the bank cannot give a guarantee, you can only lease. Then it’s: take it or leave it”. (A2)

4.3.4. Monthly Repayments and Interest Rates

“Let me give you an example: if proposal A is 1 percent and proposal B is 1.02 percent, then there must actually be a good argument for choosing the 1.02 percent proposal. They often say ‘look, you only have to pay so much per month’ and then they often make no distinction between what the total repayment is and what the interest is. This often creates a deceptive image. Of course, they always look at the repayment”. (A5)

“Cash is highly important and if you have the ambition as a company to grow, then you should not burn up your cash flow to a large extent on repayments”. (A4)

4.3.5. Tax Drivers

“VAT of course, you don’t have to pre-finance it because it happens monthly”. (A5)

“It is less of a fiscal issue now, but it certainly was in the past. Companies had the possibility with leasing to create a depreciable base more quickly through increased initial invoices: that possibility is still there, but it is being closed down”. (A1)

4.3.6. Required Flexibility

“With leasing, you do have the opportunity to spread out more: you can say I’m leasing for three years and if you notice that the cash flow doesn’t allow this, you can extend it to four years”. (A1)

“Avoiding a large cash outflow is the main reason for choosing leasing”. (A1)

“We do not apply much operating leasing options, because the family businesses would like to have that value of the asset at the end of the journey”. (A1)

“I usually try to work with off-balance leases for family businesses as much as possible. Why? It’s better in terms of balance sheet presentation and at the end you have that low value purchase option”. (A1)

5. Conclusions

5.1. Practical and Theoretical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Recommendations for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gallo, M.A.; Vilaseca, A. Finance in family business. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1996, 9, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiels, A.; Uhlaner, L.; Dekker, J. The effect of family business professionalization on dividend payout. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Haynes, K.T.; Nunez-Nickel, M.; Jacobson, K.J.; Moyano-Fuentes, J. Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Admin. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 106–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepers, J.; Voordeckers, W.; Steijvers, T.; Laveren, E. Long-Term Orientation as a Resource for Entrepreneurial Orientation in Private Family Firms: The Need for Participative Decision Making. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acedo-Ramirez, M.A.; Ayala-Calvo, J.C.; Navarrete-Martinez, E. Determinants of Capital Structure: Family Businesses versus Non-Family Firms. Czech J. Econ. Financ. 2017, 67, 80–103. [Google Scholar]

- Andres, C. Family ownership, financing constraints and investment decisions. Appl. Financ. Econ. 2011, 21, 1641–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colli, A. Family firms between risks and opportunities: A literature review. Socio Econ. Rev. 2013, 11, 577–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Mazagatos, V.; de Quevedo-Puente, E.; Castrillo, L.A. The trade-off between financial resources and agency costs in the family business: An exploratory study. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2007, 20, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.N.G.; Udell, F. The Economics of Small Business Finance: The Roles of Private Equity and Debt Markets in the Financial Growth Cycle. J. Bank. Financ. 1998, 22, 613–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.; Guzman, A.; Pombo, C.; Trujillo, M.A. Family firms and debt: Risk aversion versus risk of losing control. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2308–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgstaller, J.; Wagner, E. How do family ownership and founder management affect capital structure decisions and adjustment of SMEs? Evidence from a bank-based economy. J. Risk Financ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, S.; Fortin, A.; Callimaci, A. Family firms and the lease decision. J. Fam. Bus. Strateg. 2013, 4, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, J.H.; Chrisman, J.J.; Kellermanns, F.; Wu, Z. Family involvement and new venture debt financing. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 472–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolea, A.; Cosma, R. Leasing as a modern form of business financing. Prog. Econ. Sci. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol-Gómez-Vázquez, A.; Hernández-Cánovas, G.; Koëter-Kant, J. The use of leasing in financially constrained firms: An analysis for european SMEs. Czech J. Econ. Financ. 2019, 69, 538–557. [Google Scholar]

- Michiels, A.; Molly, V. Financing decisions in family businesses: A review and suggestions for developing the field. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2017, 30, 369–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strike, V.M. Advising the family firm: Reviewing the past to build the future. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2012, 25, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strike, V.M.; Michel, A.; Kammerlander, N. Unpacking the black box of family business advising: Insights from psychology. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2018, 31, 80–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, T.; Pearson, A.W.; Gibb Dyer, W. Advising Family Enterprise: Examining the Role of Family Firm Advisors; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Strike, V.M.; Rerup, C. Mediated sensemaking. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 880–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, F.; Hasso, T. Do we need to use an accountant? The sales growth and survival benefits to family SMEs. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2013, 26, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, H.; Shepherd, D.; Woods, C. Advising New Zealand’s family businesses: Current issues and opportunities. Univ. Auckl. Bus. Rev. 2009, 11, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Reay, T. Publishing Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Massis, A.; Kotlar, J. The case study method in family business research: Guidelines for qualitative scholarship. J. Fam. Bus. Strateg. 2014, 5, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.Q.; Chen, H.H. Environmental performance and financing decisions impact on sustainable financial development of Chinese environmental protection enterprises. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, S.; Mathews, C. ÔSmall Firm Financing: Implications from a Strategic Management Perspective. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1989, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, R.G.; Stanger, A.M. Understanding the small enterprise financial objective function. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1995, 19, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltham, T.S.; Feltham, G.; Barnett, J.J. The dependence of family businesses on a single decision-maker. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2005, 43, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, M.Á.; Tàpies, J.; Cappuyns, K. Comparison of family and nonfamily business: Financial logic and personal preferences. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2004, 17, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.C. Capital Structure Puzzle; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, M.J.; Schwartz, E.S. Corporate income taxes, valuation, and the problem of optimal capital structure. J. Bus. 1978, 51, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottardo, P.; Moisello, A.M. The capital structure choices of family firms: Evidence from Italian medium-large unlisted firms. Manag. Financ. 2014, 40, 254–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacci, S.; Cirillo, A.; Mussolino, D.; Terzani, S. The influence of family ownership dispersion on debt level in privately held firms. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 51, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Cruz, C.; Berrone, P.; De Castro, J. The bind that ties: Socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 653–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprio, L.; Croci, E.; del Giudice, A. Ownership structure, family control, and acquisition decisions. J. Corp. Financ. 2011, 17, 1636–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházka, D. The Impact of Globalization on International Finance and Accounting; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. Capital and Operating Leases; Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- Krishnan, V.S.; Moyer, R.C. Bankruptcy costs and the financial leasing decision. Financ. Manag. 1994, 23, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuli, A.; Caselli, S.; Gatti, S. Are small family firms financially sophisticated? J. Bank. Financ. 2011, 35, 2931–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, J.H.; Chrisman, J.J.; Sharma, P. Defining the Family Business by Behavior. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1999, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, K.; Hamilton, S. Roles of trust in consulting to financial families. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2004, 17, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathile, C.L. A business owner’s perspective on outside boards. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1988, 1, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budge, G.S.; Janoff, R.W. Interpreting the discourses of family business. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1991, 4, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tout, S.; Ghazzawi, K.; El Nemar, S.; Choughari, R. The major role accountants play in the decision making process. Int. J. Financ. Acc. 2014, 3, 310–315. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, W.S.; Lubatkin, M.H.; Dino, R.N.; Buchholtz, A.K. Agency relationships in family firms: Theory and evidence. Organ. Sci. 2001, 12, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, A.J.; Sweeting, R.; Goto, J. The effect of business advisers on the performance of SMEs. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baarda, B.; Bakker, E.; Fischer, T.; Julsing, M.; Peters, V.; van der Velden, T.; de Goede, M. Basisboek Kwalitatief Onderzoek: Handleiding voor het Opzetten en Uitvoeren van Kwalitatief Onderzoek; Noordhoff Uitgevers: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sobal, J. Sample extensiveness in qualitative nutrition education research. J. Nutr. Educ. 2001, 33, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everaert, P.; Sarens, G.; Rommel, J. Sourcing strategy of Belgian SMEs: Empirical evidence for the accounting services. Prod. Plan. Control 2007, 18, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhead, P.; Cowling, M. Family firm research: The need for a methodological rethink. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1998, 23, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative quality: Eight “Big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, Å. Assessing work order information quality in harvesting. Silva. Fenn. 2017, 51, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yin, R.K. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chrisman, J.J.; Chua, J.H.; Kellermanns, F.W.; Chang, E.P.C. Are family managers agents or stewards? An exploratory study in privately held family firms. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 1030–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molly, V.; Laveren, E.; Jorissen, A. Intergenerational differences in family firms: Impact on capital structure and growth behavior. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 703–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gracia, J.; Sánchez-Andújar, S. Financial structure of the family business: Evidence from a group of small Spanish firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2007, 20, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aurizio, L.; Oliviero, T.; Romano, L. Family firms, soft information and bank lending in a financial crisis. J. Corp. Financ. 2015, 33, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlova, S.; Harper, J.T.; Sun, L. Determinants of capital structure complexity. J. Econ. Bus. 2020, 110, 105905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koropp, C.; Kellermanns, F.W.; Grichnik, D.; Stanley, L. Financial decision making in family firms: An adaptation of the theory of planned behavior. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2014, 27, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith Jr, C.W.; Wakeman, L.M. Determinants of corporate leasing policy. J. Financ. 1985, 40, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrasqueiro, Z.; Nunes, P.M.; da Silva, J.V. The influence of age and size on family-owned firms’ financing decisions: Empirical evidence using panel data. Long Range Plan. 2016, 49, 723–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, R.E.; Petersen, B.C. Is the growth of small firms constrained by internal finance? Rev. Econ. Stat. 2002, 84, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.M.; Athanassiou, N.; Crittenden, W.F. Founder centrality and strategic behavior in the family-owned firm. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2000, 25, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, E.; Cirillo, A.; Saggese, S.; Sarto, F. IPO in family business: A systematic review and directions for future research. J. Fam. Bus. Strateg. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Accountant | Age | Education | Experience as External Accountant | Size of the Office |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 40 | Bachelor Accounting-Tax and Master Commercial Sciences | 15 years | 4 partners and 40 employees |

| A2 | 63 | Bachelor Accounting-Tax and Master Fiscal Law | 34 years | 2 partners and 12 employees |

| A3 | 28 | Bachelor Accounting and Tax | 6 years | 1 partner |

| A4 | 39 | Bachelor and Master in Applied Economic Sciences | 7 years | 1 partner |

| A5 | 40 | Bachelor Accounting and Tax | 8 years | 1 partner and 3 employees |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Michiels, A.; Schepers, J.; Vandekerkhof, P.; Cirillo, A. Leasing as an Alternative Form of Financing within Family Businesses: The Important Advisory Role of the Accountant. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126978

Michiels A, Schepers J, Vandekerkhof P, Cirillo A. Leasing as an Alternative Form of Financing within Family Businesses: The Important Advisory Role of the Accountant. Sustainability. 2021; 13(12):6978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126978

Chicago/Turabian StyleMichiels, Anneleen, Jelle Schepers, Pieter Vandekerkhof, and Alessandro Cirillo. 2021. "Leasing as an Alternative Form of Financing within Family Businesses: The Important Advisory Role of the Accountant" Sustainability 13, no. 12: 6978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126978

APA StyleMichiels, A., Schepers, J., Vandekerkhof, P., & Cirillo, A. (2021). Leasing as an Alternative Form of Financing within Family Businesses: The Important Advisory Role of the Accountant. Sustainability, 13(12), 6978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126978