Effect of Commercialization on Tourists’ Perceived Authenticity and Satisfaction in the Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: Case Study of Langzhong Ancient City

Abstract

1. Introduction

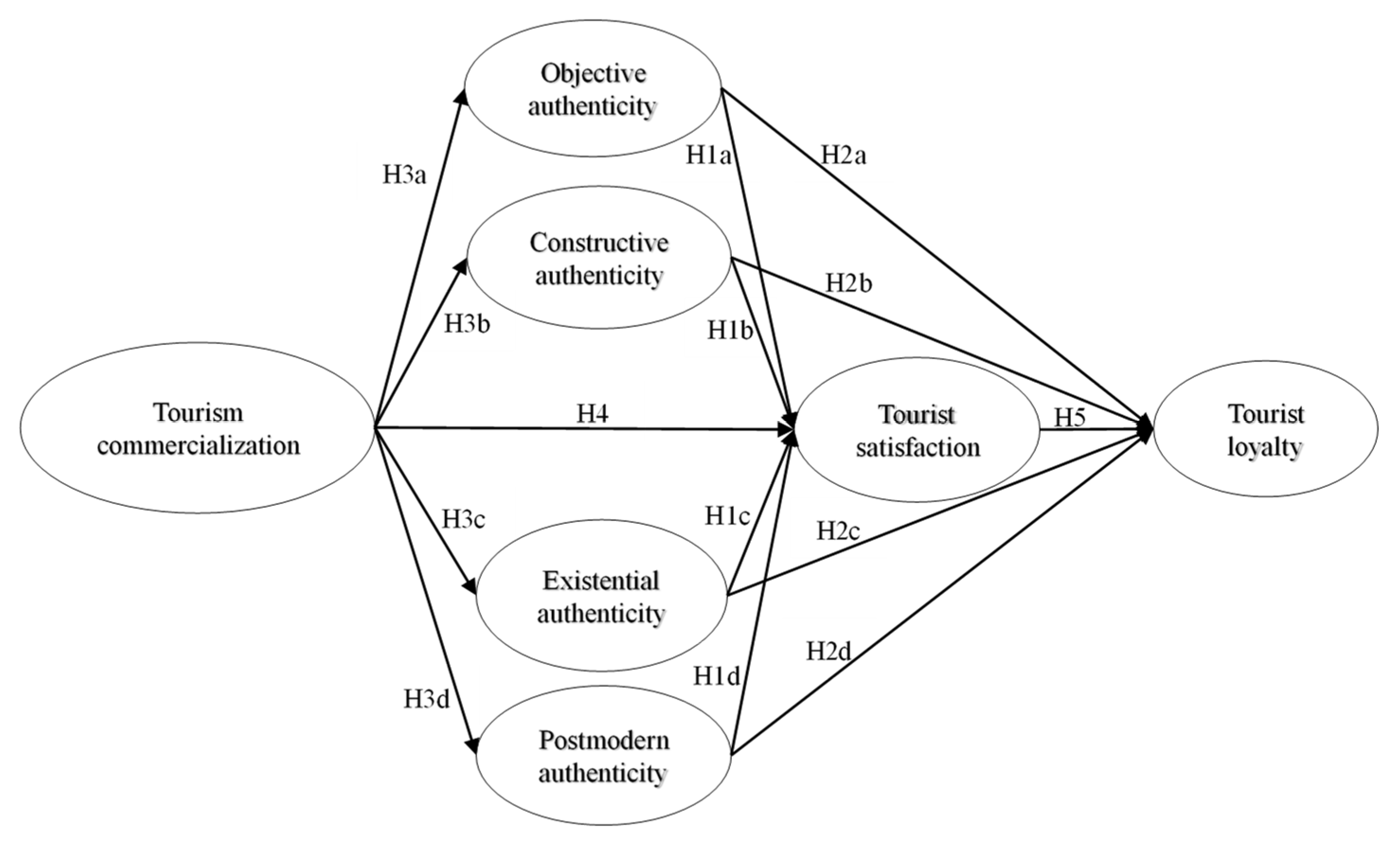

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Tourism Authenticity

2.2. Tourism Commercialization

2.3. Tourist Satisfaction and Loyalty

3. Research Methods

3.1. Research Site

3.2. Measurement

| Construct | Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Objective authenticity | OA1: Historic buildings are well preserved | [8,67,68] |

| OA2: Layout and furnishings remain as original appearance | ||

| OA3: Recognized by authoritative departments and experts | ||

| OA4: History clearly documented | ||

| OA5: Attractions are mostly genuine | ||

| Constructive authenticity | CA1: Reflect the local ancient living environment | [8,67,68] |

| CA2: Represent the local past history | ||

| CA3: Represent the local past culture | ||

| CA4: Represent local past traditions | ||

| CA5: Many attractions look like real | ||

| Existential authenticity | EA1: Traveling here can free my body from daily work and life and make me more relaxed and feel like myself | [19] |

| EA2: Traveling here can improve myself, realize my dreams and even provide me with a sense of achievement | ||

| EA3: Traveling here can promote family relationship and intimacy | ||

| EA4: Traveling here, I can contact local peoples in an authentic and friendly way | ||

| EA5: Traveling here, I can contact other tourists in an authentic and natural way, without considering the difference of status or class | ||

| Postmodern authenticity | PA1: The buildings I encounter here can be contrived, reproductions or simulations of the originals, even through imagination without reference | [19,37] |

| PA2: The local people I met here can just be acting, imitating or even imagined Indigenous people | ||

| PA3: There is no absolute line between the real and the fake, since sometimes it is impossible to find the original as a reference | ||

| PA4: Modern technology can make the inauthentic look more authentic | ||

| PA5: I just want to have a good time and enjoy it; I don’t care whether it is authentic or not | ||

| Tourism commercialization | TC1: The whole commercial atmosphere is higher | [21,37] |

| TC2: Many shops cater to tourists | ||

| TC3: Many kinds of tourism commodities | ||

| TC4: Most tourist commodities are produced by modern techniques | ||

| TC5: Many exotic business cultures | ||

| Tourist satisfaction | TS1: Overall satisfaction | [8,69] |

| TS2: All expectations are realized | ||

| TS3: Happy and enjoyable | ||

| TS4: Time and money spent are satisfactory | ||

| Tourist loyalty | TL1: Will revisit this place again | [1,20,64] |

| TL2: Will recommend this place to relatives, friends and acquaintances | ||

| TL3: Will share this travel experience through social media |

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Evaluation of Measurement Models

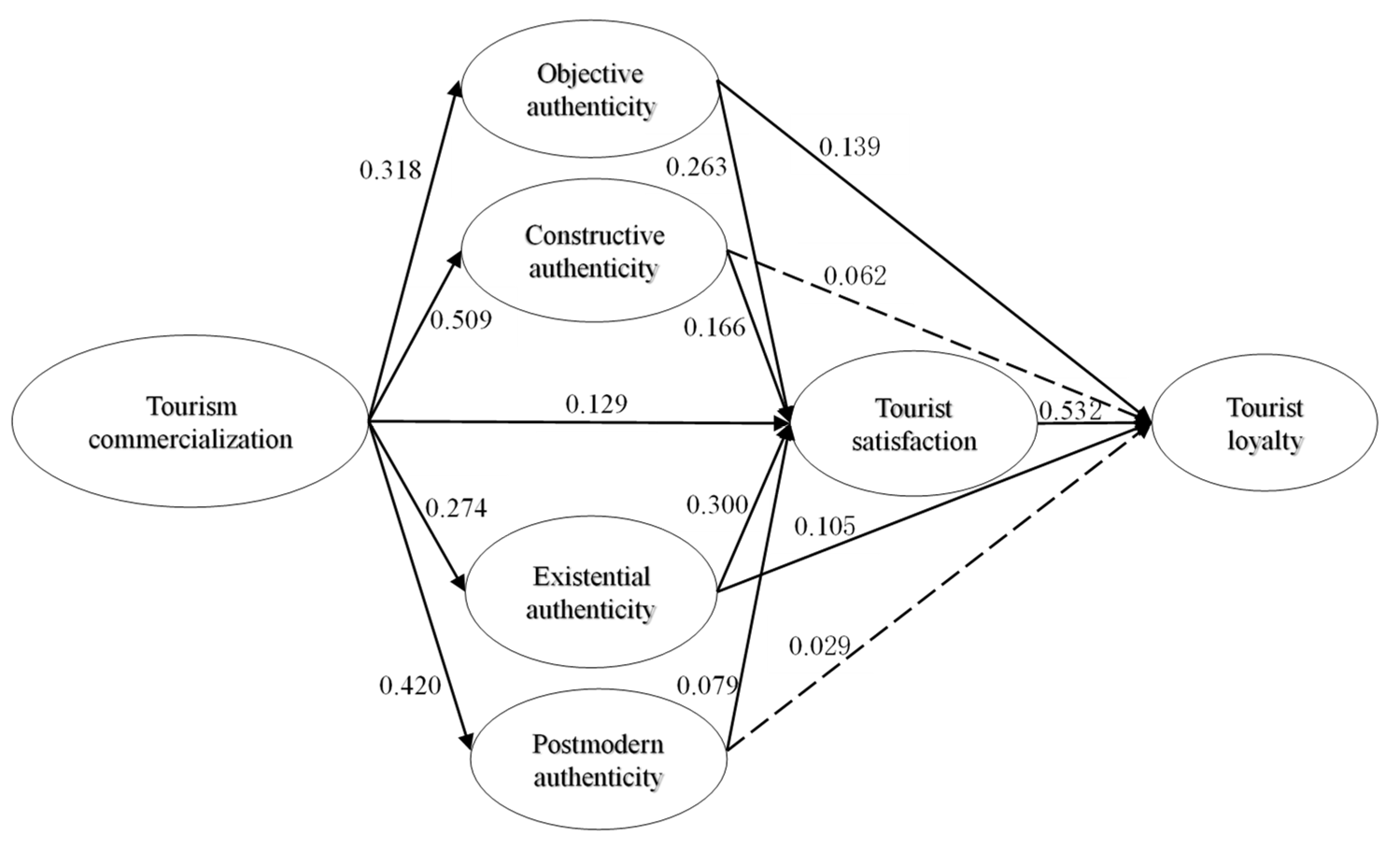

4.3. Evaluation of the Structural Model

5. Conclusions and Discussions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kolar, T.; Zabkar, V. A consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Liu, Y.C. Deconstructing the internal structure of perceived authenticity for heritage tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 2134–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakis, A. The convergence process in heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 795–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Choi, B.-K.; Lee, T.J. The role and dimensions of authenticity in heritage tourism. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, C.J.; Reisinger, Y. Understanding existential authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D.; Healy, R.; Sills, E. Staged authenticity and heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Phau, I.; Hughes, M.; Li, Y.F.; Quintal, V. Heritage tourism in Singapore Chinatown: A perceived value approach to authenticity and satisfaction. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 981–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Chi, C.G.; Liu, Y. Authenticity, involvement, and image: Evaluating tourist experiences at historic districts. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Quintero, A.M.; González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Paddison, B. The mediating role of experience quality on authenticity and satisfaction in the context of cultural-heritage tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 23, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halewood, C.; Hannam, K. Viking heritage tourism: Authenticity and commodification. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wan, X.; Fan, X. Rethinking authenticity in the implementation of China’s heritage conservation: The case of Hongcun Village. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Ma, J. A structural model of host authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 55, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Zheng, Q.; Ng, P. A study on the coordinative green development of tourist experience and commercialization of tourism at cultural heritage sites. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Song, C.; Sigley, G. The uses of reconstructing heritage in China: Tourism, heritage authorization, and spatial transformation of the Shaolin Temple. Sustainability 2019, 11, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, J.; Edelheim, J.R. Rethinking traditional Chinese culture: A consumer-based model regarding the authenticity of Chinese calligraphic landscape. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronis, A.; Hampton, R.D. Consuming the authentic Gettysburg: How a tourist landscape becomes an authentic experience. J. Consum. Behav. 2008, 7, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Guo, J.; Wu, Y. Investigating the structural relationships among authenticity, loyalty, involvement, and attitude toward world cultural heritage sites: An empirical study of Nanjing Xiaoling Tomb, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, D.; Curran, R.; O’Gorman, K.; Taheri, B. Visitors’ engagement and authenticity: Japanese heritage consumption. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Fu, X.; Yu, L.; Jiang, L. Authenticity and loyalty at heritage sites: The moderation effect of postmodern authenticity. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Lin, V.S.; Jin, W.; Luo, Q. The authenticity of heritage sites, tourists’ quest for existential authenticity, and destination loyalty. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 1032–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Su, X. Sudies on torism commercialization in historic towns. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2004, 59, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.; Yang, X.; Wassler, P.; Wang, D.; Lin, P.; Liu, Z. Contesting the commercialization and sanctity of religious tourism in the Shaolin Monastery, China. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitt, G. Consuming heritage: Perceived historical authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 835–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Butler, R.; Airey, D. The core of heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X. Commodification and the selling of ethnic music to tourists. Geoforum 2011, 42, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Lin, B.; Chen, Y.; Tseng, S.; Gao, J. Can commercialization reduce tourists’ experience quality? Evidence from Xijiang Miao Village in Guizhou, China. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 43, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. What facilitates a festival tourist? Investigating tourists’ experiences at a local community festival. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickly-Boyd, J.M. Authenticity & aura: A Benjaminian approach to tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yin, P. Testing the structural relationships of tourism authenticities. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Lesure Class; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Culler, J. Semiotics of tourism. Am. J. Semiot. 1981, 1, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, E.M. Abraham Lincoln as authentic reproduction: A critique of postmodernism. Am. Anthropol. 1994, 96, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Cohen, S.A. Authentication: Hot and cool. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1295–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eco, U. Travels in Hyperreality; Harcourt Brace & Company: San Diego, CA, USA; New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jamal, T. Touristic quest for existential authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, K.; Martinec, R. Consumer perceptions of iconicity and indexicality and their influence on assessments of authentic market offerings. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Customized authenticity begins at home. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkono, M. African and Western tourists: Object authenticity quest? Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 41, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Chao, R.-F. How experiential consumption moderates the effects of souvenir authenticity on behavioral intention through perceived value. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.F. The bamboo-beating dance in Hainan, China: Authenticity and commodification. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, A.R. The limits of commodification in traditional Irish music sessions. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 2007, 13, 703–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, X.; Tang, S. Preliminary study on tourism development and commercialization in ancient towns. Tour. Trib. 2006, 21, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gnoth, J.; Wang, N. Authentic knowledge and empathy in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, G.L.; Joseph, P.K. Interpretations of tourism as commodity. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, R. Commodification, culture and tourism. Tour. Stud. 2002, 2, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, D.J. Culture by the Pound: An Anthropological Perspective on Tourism as Cultural Commoditization in Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism; Smith, V.L., Ed.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1977; pp. 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, S.; Xiao, H.; Zhou, L. Commodification and perceived authenticity in commercial homes. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 71, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, P.; Bao, J. Income distribution, tourist commercialisation, and Hukou status: A socioeconomic analysis of tourism in Xidi, China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2008, 11, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Bao, J. Tourism commodification in China’s historic towns and villages: Re-examining the creative destruction model. Tour. Trib. 2015, 30, 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Yan, T.; Zhu, X. Commodification of Chinese heritage villages. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castéran, H.; Roederer, C. Does authenticity really affect behavior? The case of the Strasbourg Christmas Market. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Teo, P. Tourism politics in Lijiang, China: An analysis of state and local interactions in tourism development. Tour. Geogr. 2008, 10, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A.; Neumann, Y.; Reichel, A. Dimentions of tourist satisfaction with a destination area. Ann. Tour. Res. 1978, 5, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wall, G. Authenticity in ethnic tourism: Domestic tourists’ perspectives. Curr. Issues Tour. 2009, 12, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. Tourists’ perceptions of ethnic tourism in Lugu Lake, Yunnan, China. J. Herit. Tour. 2012, 7, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoondnejad, A. Tourist loyalty to a local cultural event: The case of Turkmen handicrafts festival. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Goulden, M. A comparative analysis of international tourists’ satisfaction in Mongolia. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1331–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araña, J.E.; León, C.J. Correcting for scale perception bias in tourist satisfaction surveys. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 772–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fu, X.; Cai, L.A.; Lu, L. Destination image and tourist loyalty: A meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Sharing tourism experiences: The posttrip experience. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Tsai, D.C. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Guo, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z. Scenic image research based on big data analysis: Take China’s four ancient cities as an example. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2020, 14, 2769–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.H.; Cheung, C. Chinese heritage tourists to heritage sites: What are the effects of heritage motivation and perceived authenticity on satisfaction? Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 1155–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatori, A.; Smith, M.K.; Puczko, L. Experience-involvement, memorability and authenticity: The service provider’s effect on tourist experience. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Yoon, Y.S.; Lee, S.K. Investigating the relationships among perceived value, satisfaction, and recommendations: The case of the Korean DMZ. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Tu, Q.; Liu, F. Evolution characteristics and mechanism of tourism commercialization development in a religious heritage site: A case study of Shaolin Temple Scenic Area. Geogr. Res. 2015, 34, 1781–1794. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3.3.3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1974, 36, 111–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisser, S. A predictive approach to the random effect model. Biometrika 1974, 61, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Adv. Int. Mark. 2009, 20, 277–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. Beyond authenticity and commodification. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckercher, B.; du Cros, H. Cultural Tourism: The Partnership between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra, D. Authenticity of the objectively authentic. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | n | Percentage | Category | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | - | - | Monthly income (USD *) | - | - |

| Male | 325 | 52.6 | <312.5 | 89 | 14.4 |

| Female | 293 | 47.4 | 312.5–781.3 | 275 | 44.5 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 781.4–1250 | 168 | 27.2 |

| Age | - | - | 1250.1–1875 | 47 | 7.6 |

| 16–19 | 54 | 8.7 | >1875 | 34 | 5.5 |

| 20–29 | 183 | 29.6 | Missing | 5 | 0.8 |

| 30–39 | 200 | 32.4 | Travel times before | - | - |

| 40–49 | 110 | 17.8 | 0 | 248 | 40.1 |

| 50–59 | 54 | 8.7 | 1 | 172 | 27.8 |

| ≥60 | 16 | 2.6 | 2–3 | 131 | 21.2 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.2 | 4–6 | 29 | 4.7 |

| Education | - | - | ≥7 | 38 | 6.1 |

| Middle school or below | 41 | 6.6 | Missing | 0 | 0 |

| High or technical school | 165 | 26.7 | First-order travel motivation | - | |

| Junior college | 153 | 24.8 | Relax physically and mentally | 182 | 29.4 |

| Undergraduate | 191 | 30.9 | Enhance the relationship between family or friends | 129 | 20.9 |

| Master | 50 | 8.1 | Visit historical culture sites | 85 | 13.8 |

| Ph.D. | 15 | 2.4 | Increase knowledge | 54 | 8.7 |

| Missing | 3 | 0.5 | Satisfy historical interest | 47 | 7.6 |

| Occupation | - | - | Enjoy a peaceful atmosphere | 36 | 5.8 |

| State-owned enterprises and institutions | 175 | 28.3 | Discover new places and things | 46 | 7.4 |

| Government staff | 28 | 4.5 | Others | 14 | 2.3 |

| Employee | 34 | 5.5 | Missing | 25 | 4.0 |

| Businessman | 55 | 8.9 | Travel Companies | ||

| Teaching staff | 52 | 8.4 | None | 51 | 8.3 |

| Student | 90 | 14.6 | Family member | 198 | 32.0 |

| Retiree | 36 | 5.8 | Friend | 257 | 41.6 |

| Freelance | 130 | 21.0 | Lover | 45 | 7.3 |

| Others | 17 | 2.8 | Tourist groups | 52 | 8.4 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.2 | Others | 9 | 1.5 |

| - | - | - | Missing | 6 | 1.0 |

| Construct/Variables | Mean | S.D. | Loading | CR | α | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism commercialization | 5.476 | - | - | 0.819 | 0.706 | 0.532 |

| TC1 | 5.304 | 1.236 | 0.722 | - | - | - |

| TC2 | 5.638 | 1.128 | 0.744 | - | - | - |

| TC3 | 5.535 | 1.162 | 0.794 | - | - | - |

| TC4 | 5.428 | 1.277 | 0.650 | - | - | - |

| Objective authenticity | 5.305 | - | - | 0.839 | 0.767 | 0.513 |

| OA1 | 5.055 | 1.642 | 0.758 | - | - | - |

| OA2 | 5.326 | 1.367 | 0.774 | - | - | - |

| OA3 | 5.599 | 1.052 | 0.735 | - | - | - |

| OA4 | 5.673 | 1.050 | 0.700 | - | - | - |

| OA5 | 4.871 | 1.658 | 0.602 | - | - | - |

| Constructive authenticity | 5.598 | - | - | 0.895 | 0.843 | 0.680 |

| CA1 | 5.368 | 1.221 | 0.772 | - | - | - |

| CA2 | 5.654 | 1.105 | 0.839 | - | - | - |

| CA3 | 5.647 | 1.143 | 0.859 | - | - | - |

| CA4 | 5.723 | 1.167 | 0.827 | - | - | - |

| Existential authenticity | 5.539 | - | - | 0.837 | 0.756 | 0.508 |

| EA1 | 5.419 | 1.358 | 0.736 | - | - | - |

| EA2 | 4.982 | 1.497 | 0.750 | - | - | - |

| EA3 | 5.542 | 1.168 | 0.738 | - | - | - |

| EA4 | 5.579 | 1.174 | 0.709 | - | - | - |

| EA5 | 5.273 | 1.283 | 0.621 | - | - | - |

| Postmodern authenticity | 5.014 | - | - | 0.851 | 0.769 | 0.588 |

| PA1 | 4.945 | 1.387 | 0.750 | - | - | - |

| PA2 | 4.937 | 1.484 | 0.792 | - | - | - |

| PA3 | 5.023 | 1.277 | 0.738 | - | - | - |

| PA4 | 5.151 | 1.271 | 0.787 | - | - | - |

| Tourist satisfaction | 5.551 | - | - | 0.864 | 0.790 | 0.615 |

| TS1 | 5.647 | 1.048 | 0.813 | - | - | - |

| TS2 | 5.425 | 1.154 | 0.818 | - | - | - |

| TS3 | 5.667 | 1.055 | 0.813 | - | - | - |

| TS4 | 5.467 | 1.298 | 0.685 | - | - | - |

| Tourist loyalty | 5.568 | - | - | 0.873 | 0.781 | 0.697 |

| TL1 | 5.479 | 1.223 | 0.871 | - | - | - |

| TL2 | 5.596 | 1.161 | 0.890 | - | - | - |

| TL3 | 5.629 | 1.207 | 0.735 | - | - | - |

| Construct | TC | OA | CA | EA | PA | TS | TL | R2 | Q2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism commercialization | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Objective authenticity | 0.423 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.101 | 0.041 |

| Constructive authenticity | 0.652 | 0.508 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.259 | 0.174 |

| Existential authenticity | 0.368 | 0.623 | 0.509 | - | - | - | - | 0.075 | 0.037 |

| Postmodern authenticity | 0.560 | 0.185 | 0.477 | 0.318 | - | - | - | 0.176 | 0.101 |

| Tourist satisfaction | 0.540 | 0.665 | 0.608 | 0.711 | 0.369 | - | - | 0.464 | 0.281 |

| Tourist loyalty | 0.424 | 0.612 | 0.548 | 0.642 | 0.322 | 0.885 | - | 0.532 | 0.361 |

| Hypothesis Relationships | Coefficient β | t-Value | Supported? |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: Objective authenticity → Tourist satisfaction | 0.263 | 6.023 *** | Yes |

| H1b: Constructive authenticity → Tourist satisfaction | 0.166 | 3.836 *** | Yes |

| H1c: Existential authenticity → Tourist satisfaction | 0.300 | 7.361 *** | Yes |

| H1d: Postmodern authenticity → Tourist satisfaction | 0.079 | 1.976 * | Yes |

| H2a: Objective authenticity → Tourist loyalty | 0.139 | 3.713 *** | Yes |

| H2b: Constructive authenticity → Tourist loyalty | 0.062 | 1.632 | No |

| H2c: Existential authenticity → Tourist loyalty | 0.105 | 2.626 ** | Yes |

| H2d: Postmodern authenticity → Tourist loyalty | 0.029 | 0.897 | No |

| H3a: Tourism commercialization → Objective authenticity | 0.318 | 7.664 *** | Yes |

| H3b: Tourism commercialization → Constructive authenticity | 0.509 | 15.045 *** | Yes |

| H3c: Tourism commercialization → Existential authenticity | 0.274 | 6.283 *** | Yes |

| H3d: Tourism commercialization → Postmodern authenticity | 0.420 | 11.549 *** | Yes |

| H4: Tourism commercialization → Tourist satisfaction | 0.129 | 3.310 *** | Yes |

| H5: Tourist satisfaction → Tourist loyalty | 0.532 | 13.505 *** | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, T.; Yin, P.; Peng, Y. Effect of Commercialization on Tourists’ Perceived Authenticity and Satisfaction in the Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: Case Study of Langzhong Ancient City. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126847

Zhang T, Yin P, Peng Y. Effect of Commercialization on Tourists’ Perceived Authenticity and Satisfaction in the Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: Case Study of Langzhong Ancient City. Sustainability. 2021; 13(12):6847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126847

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Tonghao, Ping Yin, and Yuanxiang Peng. 2021. "Effect of Commercialization on Tourists’ Perceived Authenticity and Satisfaction in the Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: Case Study of Langzhong Ancient City" Sustainability 13, no. 12: 6847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126847

APA StyleZhang, T., Yin, P., & Peng, Y. (2021). Effect of Commercialization on Tourists’ Perceived Authenticity and Satisfaction in the Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: Case Study of Langzhong Ancient City. Sustainability, 13(12), 6847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126847