The Impact of the EU IUU Regulation on the Sustainability of the Thai Fishing Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. The impact of the “Yellow Card” on the Thai Fishing Industry

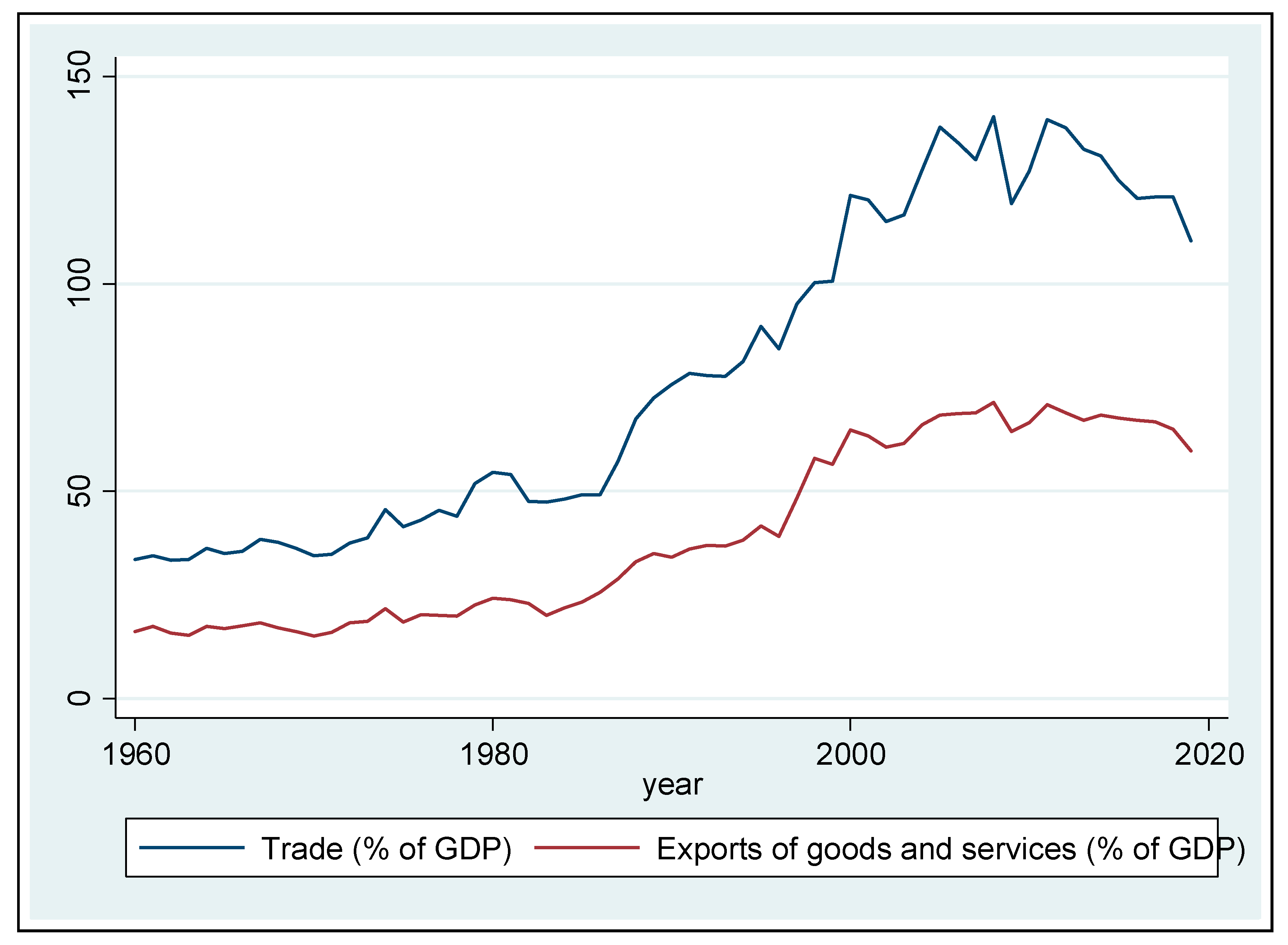

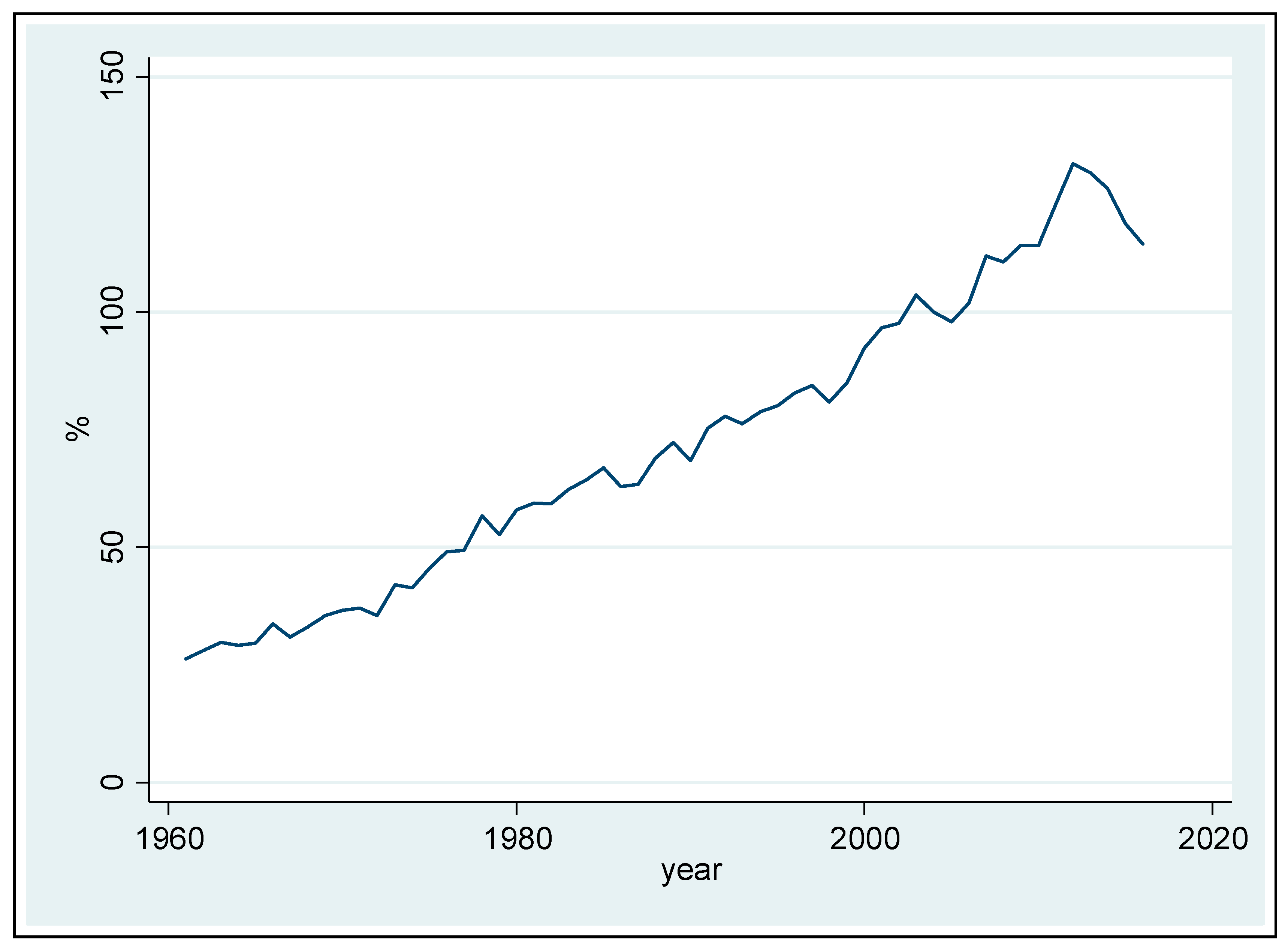

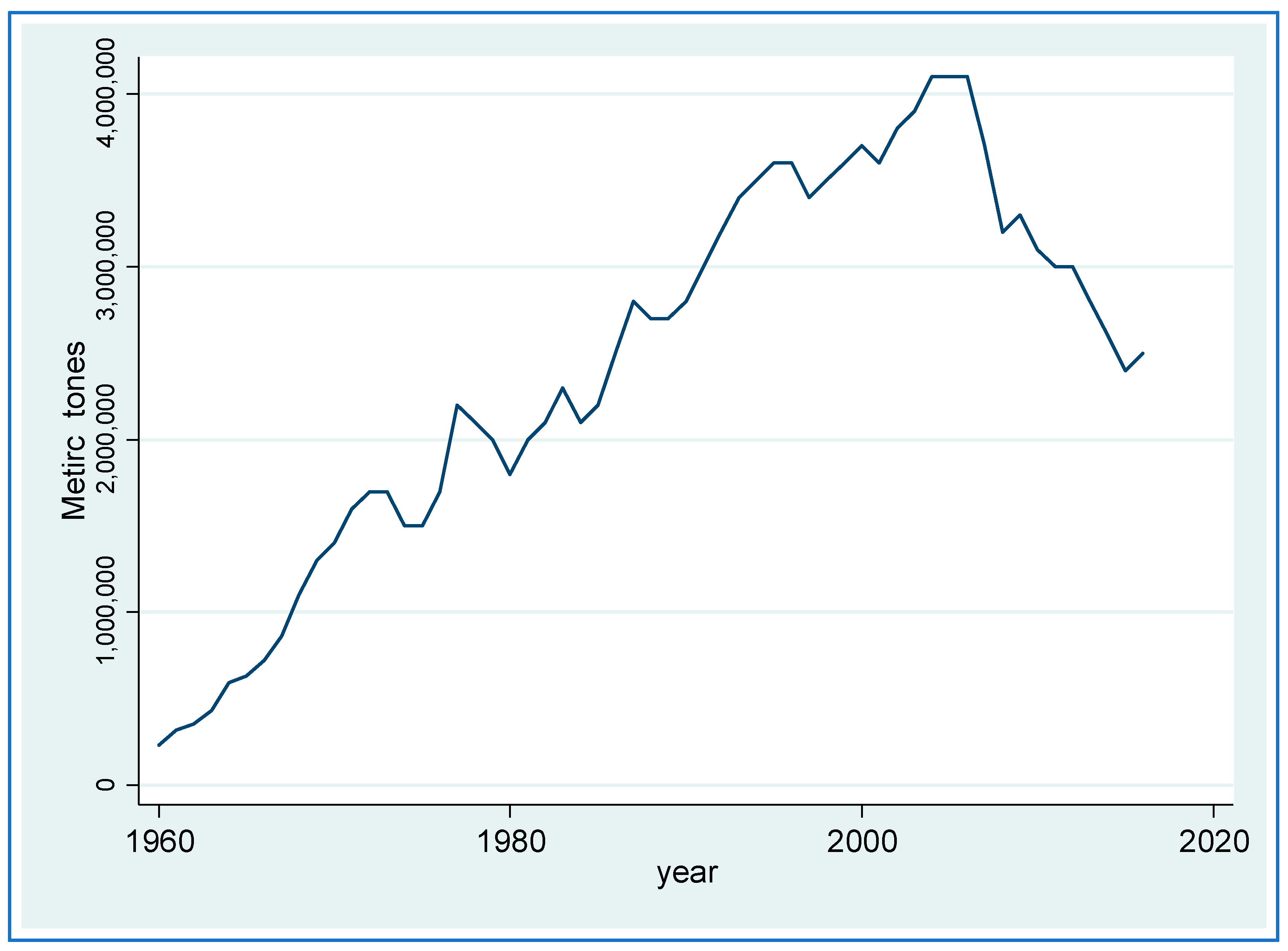

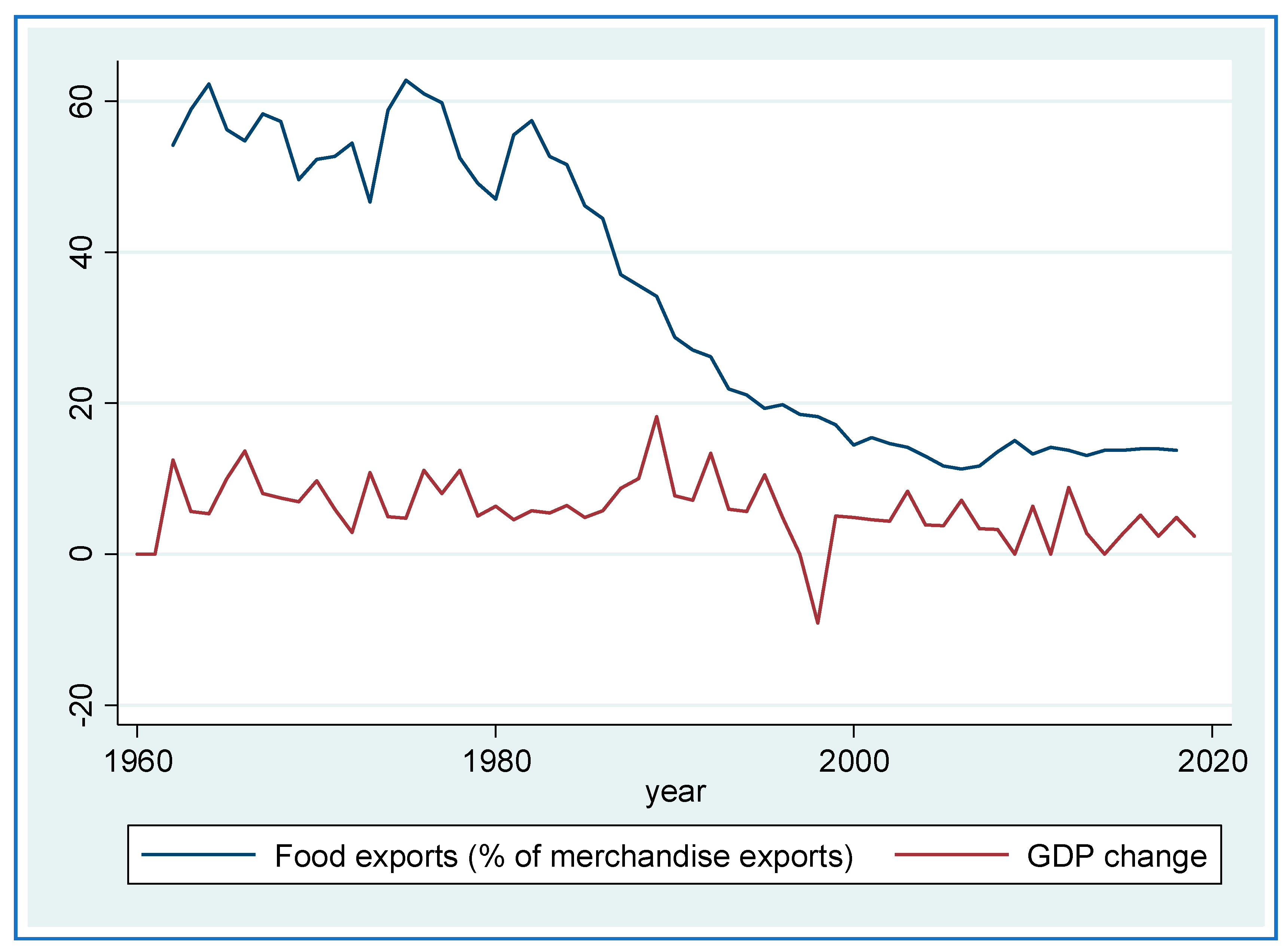

3.1. Thai’s Fishing Industry Overview

3.2. Impact on Sustainability

3.3. Legal Impact

3.4. Economic Impact

4. The Effectiveness of the EU IUU Regulation: The Thai Government’s Reaction and Sustainability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kroodsma, D.A.; Mayorga, J.; Hochberg, T.; Miller, N.A.; Boerder, K.; Ferretti, F.; Wilson, A.; Bergman, B.; White, T.D.; Block, B.A.; et al. Tracking the global footprint of fisheries. Science 2018, 359, 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO). World Food and Agriculture—Statistical Pocketbook; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing. 2021. Available online: www.fao.org/iuu-fishing/en/ (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Smith, N. Human Trafficking and Violence Still Rife in Thai Fishing Industry. The Telegraph 2018. TEIR is the Level in the Trafficking in Persons (Tip) Report Based on Countries’ Acknowledgement and Efforts against Human Trafficking. The Ranking System Categorized into Four Levels, which Are Tier 1, Tier 2, Tier 2 Watch List and Tier 3, which Is the Lowest. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/01/23/human-traffickingand-violence-rife-thai-fishing-industry-uks/ (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- United Nations (UN). Non-Tariff Measures: Evidence from Selected Developing Countries and Future Research Agenda, Developing Countries in International Trade Studies; UNCTAD/DITC/TAB/2009/3; UN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; Volume xix, p. 143. [Google Scholar]

- World Trade Organization (WTO). Technical Information on Technical Barriers to Trade; WTO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/tbt_e/tbt_e.htm (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Banks, M. EU Lifts Thailand’s Yellow Card on Tackling Illegal Fishing. The Parliament. 2019. Available online: https://www.theparliamentmagazine.eu/news/article/eu-lifts-thailands-yellow-card-on-tackling-illegal-fishing (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- United States International Trade Commission (USITC). USITC to Investigate Extent of Illegal, Unreported, and Un-Regulated Seafood Imports and Impact on U.S. Commercial Fishermen; News Releases 20-006, Inv. No. 332-575; USITC: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- United States Department of the Treasury (USDOT). Treasury Sanctions Chinese Government Officials in Connection with Serious Human Rights Abuse in Xinjiang; Press Releases 22 March 2021; USDOT: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Kulanujaree, N.; Saline, K.R.; Noranarttragoon, P.; Yakupitiyage, A. The Transition from Unregulated to Regulated Fishing in Thailand. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Agricultural Information Network (GAIN). Thailand and EU Seafood Yellow Card Will Lead U.S. Exports to Rise. 2019. Available online: https://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Thailand%20and%20EU%20Seafood%20Yellow%20Card%20Will%20Lead%20U.S.%20Exports%20to%20Rise_Bangkok_Thailand_3-11-2019.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Xiong, B.; Beghin, J. Does European aflatoxin regulation hurt groundnut exporters from Africa? Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2011, 39, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Kim, J. TBT and SPS impacts on Korean exports to China: Empirical analysis using the PPML method. Asian Pac. Econ. Lit. 2017, 31, 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Kim, J. The impact of TBT and SPS measures on Japanese and Korean exports to China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.Y.; Bang, H.K.; Lee, B.R.; Yoo, S.B. A proposal to lower non-tariff barriers of China, Japan and Korea. World Econ. Brief 2015, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saisunthorn, C. Control of IUU Fishing under International and Thai Laws. J. Law Thammasat Univ. 2018, 47, 416–436. [Google Scholar]

- Zwoelfer, R. The economic impact of IUU-fishing and its countermeasures on small scale fishermen in Thailand: A case study of Baan Khan Kradai. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 416, 012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandaruwan, K.P.G.L.; Weerasooriya, S.A. Non-Tariff Measures and Sustainable Development: The Case of the European Union Import Ban on Seafood from Sri Lanka; ARTNeT Working Paper Series, No. 185; Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade (ARTNeT): Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi, V. Thailand’s Investment Outlook for 2018. Asean Briefing 2018. Available online: https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/thailands-investment-outlook-2018/ (accessed on 9 April 2021).

- Kightley, N. Ethical Trading Initiative, Thailand’s Seafood Industry, Thai Government Starts to Act on Fishing Industry Problems. 2018. Available online: https://www.ethicaltrade.org/blog/thai-government-starts-to-act-fishing-industry-problems (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Yenpoeng, T. Fisheries Country Profile: Thailand, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center (SEAFDEC): Bangkok, Thailand. 2017. Available online: http://www.seafdec.org/fisheries-country-profile-thailand/ (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- European Market Observatory for Fisheries and Aquaculture products, (EUMOFA). The EU Fish Market, 2018 Edition ed; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Du Pisani, J.A. Sustainable development—Historical roots of the concept. Environ. Sci. 2006, 3, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- While All States Possess Territory, Title to Territory is Based on its State Sovereignty. Territorial Sovereignty is a Basis for the Territorial Jurisdiction. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/international-law/sovereignty-over-territory/4A3BF4AE9CFEE0CD134557C50F4781D9 (accessed on 5 May 2019).

- Wolfrum, R.; Stoll, P.T.; Seibert-Fohr, A. (Eds.) WTO—Technical Barriers and SPS Measures; Max Planck Commentaries on World Trade Law; Martinus Nijhoff Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 186–200. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EU’s IUU Regulation, COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 1005/2008 of 29 September 2008 Establishing a Community System to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing, Amending Regulations (EEC) No 2847/93, (EC) No 1936/2001 and (EC) No 601/2004 and Repealing Regulations (EC) No 1093/94 and (EC) No 1447/1999; Article 12 Catch Certificates; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- The Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF). The EU IUU Regulation Analysis: Implementation of EU Seafood Import Controls; Oceana: Washington, DC, USA; The Pew Charitable Trusts: Philadelphia, PA, USA; WWF: Gland, Switzerland, 2017; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EU Rules To combat IUU Fishing. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/oceans-and-fisheries/fisheries/rules/illegal-fishing_en (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- European Union. 4. “COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 1005/2008”, Article 37. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/eur/2008/1005/contents (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Young, M.A. Trade-Related Measures to Address Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing; International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD): Geneva, Switzerland; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2015; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- World Trade Organization (WTO). Communication from the CCAMLR Secretariat; /W/148. WT/CTE.; WTO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- The Siam Commercial Bank Public Company Limited Economic Intelligence Center (SCM). The EU Yellow Card is a Wake-Up Call Before Trade Sanctions; SCM: Bangkok, Thailand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- InfoQuest Limited, Kasikorn Research Center. Thai Fishery Exports to the EU Are Expected to Return. 2019. Available online: https://kasikornresearch.com/en/analysis/k-econ/business (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- European Commission (EC). EU Vietnam Trade Agreement-Memo. 2018. Available online: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/press/index.cfm?id=1922 (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- European Commission (EC). Questions and Answers—Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing in General and in Thailand. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_19_201 (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Thai Embassy. Highlights of Thailand’s New Fisheries Legislation. 2015. Available online: https://www.thaiembassy.be/2015/11/18/highlights-of-thailands-new-fisheries-legislation/?lang=en (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Thailand. Thailand’s Reform of Fishing License Regime, 25 February 2016. Available online: https://thaiembdc.org/2016/03/07/thailands-fisheries-reform/ (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- International Labor Organization (ILO). Measuring Progress towards Decent Work in Thai Fishing and Seafood Industry. 2018. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/asia/media-centre/news/WCMS_619724/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- U.S. Department of State. 2017 Trafficking in Persons Report Thailand. 2017. Available online: https://www.state.gov/reports/2017-trafficking-in-persons-report/thailand/ (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Thai’s Department of Labor Protection and Welfare. The Ministry of Labor Announced the Enactment of Labor Protection Law in Sea Fishery Work. 26 June 2019. Available online: https://www.labour.go.th/index.php/en/more/47745-the-ministry-of-labour-announced-the-enactment-of-labour-protection-law-in-sea-fishery-work (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Royal Thai Government. Thailand’s Fisheries Reform: Progress and Way forward in the Fight against IUU Fishing and Forced Labor. March 2016. Available online: https://thaiembdc.org/2016/03/07/thailands-fisheries-reform/ (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Sundström, A. Exploring Performance-Related Pay as an Anticorruption Tool. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 2017, 54, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österblom, H.; Sumaila, U.R.; Bodin, Ö.; Hentati-Sundberg, J.; Press, A.J. Adapting to Regional Enforcement: Fishing Down the Governance Index. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ILO. Endline Research Findings on Fishers and Seafood Workers in Thailand; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The Freedom Fund and Humanity United. Tracking Progress: Assessing Business Responses to Forced Labour and Human Trafficking in the Thai Seafood Industry; 2019; p. 13. Available online: http://www.praxis-labs.com/uploads/2/9/7/0/29709145/09_hu_report_final.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2020).

| Year Export | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World | HS_03 | 3075 | 3335 | 3057 | 2196 | 2102 | 1753 | 1783 | 1787 | 1686 | 1180 |

| HS_16 | 5911 | 7034 | 7049 | 6760 | 6249 | 5945 | 5751 | 6094 | 6387 | 6027 | |

| EU | HS_03 | 486 | 548 | 447 | 320 | 365 | 197 | 196 | 206 | 164 | 174 |

| HS_16 | 1634 | 1981 | 1596 | 1602 | 1491 | 1262 | 1119 | 1116 | 476 | 1122 |

| Year Category | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish, fresh/chilled, excluding fish fillets and other fish meat (0302) | 51.8 | 45.1 | 42.8 | 33.4 |

| Fish, frozen, excluding fish fillets and other fish meat (0303) | 173.8 | 127.4 | 121.6 | 156.6 |

| Fish fillets and other fish meat, fresh/chilled/frozen (0304) | 317.6 | 289.1 | 281.7 | 249.1 |

| Fish, dried, salted, smoked (0305) | 110.2 | 95.1 | 104.9 | 90.3 |

| Mollusks, live/fresh/chilled/frozen/dried (0307) | 448.1 | 364.1 | 352.8 | 373.8 |

| Shrimps and prawns, frozen/not frozen, prepared or preserved (030617, 0330626, 030627, 160521, 160529) | 1974.30 | 1644.20 | 1952.80 | 1873.80 |

| Tuna, skipjack, and bonito, prepared/preserved (160414) | 2354.80 | 1966.20 | 1978.80 | 2061.70 |

| Sardines, sardinella, and brisling or sprats, prepared/preserved (160413110) | 168.8 | 154.5 | 116.9 | 108 |

| Salmon, prepared/preserved (1604111000, 16041190000) | 122.3 | 132.8 | 100.2 | 113.8 |

| Cuttlefish, squid, octopus, live/frozen/chilled (030741, 030742, 03074910001, 03074910002, 03074910003, 030743, 030751, 030752, 03075910000) | 349.8 | 289.8 | 283.5 | 345 |

| Other prepared/preserved fish/seafood | 578.8 | 533.8 | 514.6 | 725.9 |

| Total export | 6300.50 | 5352.30 | 5567.10 | 5786.40 |

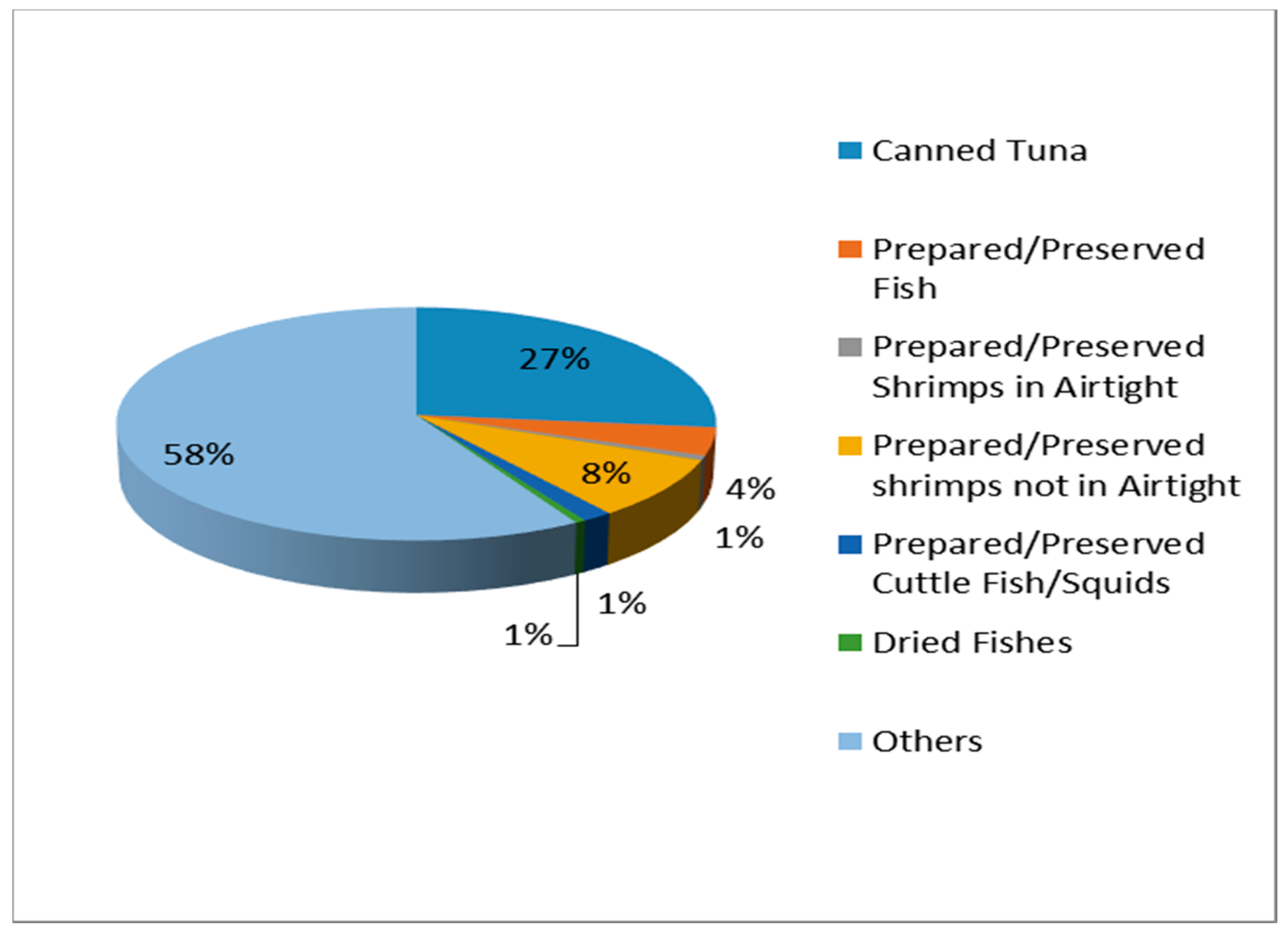

| Items | HS Code | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canned Tuna | 160414 | 210,145 | 174,862 | 131,641 | 127,211 | 123,494 |

| Prepared/Preserved Fish | 160420 | 30,231 | 29,745 | 28,126 | 21,889 | 22,473 |

| Prepared/Preserved Shrimps in Airtight | 160529 | 5237 | 3524 | 3961 | 8326 | 10,394 |

| Prepared/Preserved shrimps not in Airtight | 160521 | 66,347 | 21,895 | 20,305 | 16,340 | 15,504 |

| Prepared/Preserved Cuttlefish/Squids | 160554 | 12,013 | 8062 | 10,940 | 12,011 | 10,898 |

| Dried Fishes | 30559 | 4244 | 3279 | 2564 | 804 | 654 |

| Others | Others | 459,163 | 299,807 | 303,390 | 280,163 | 245,774 |

| 787,380 | 541,174 | 500,927 | 466,744 | 429,191 |

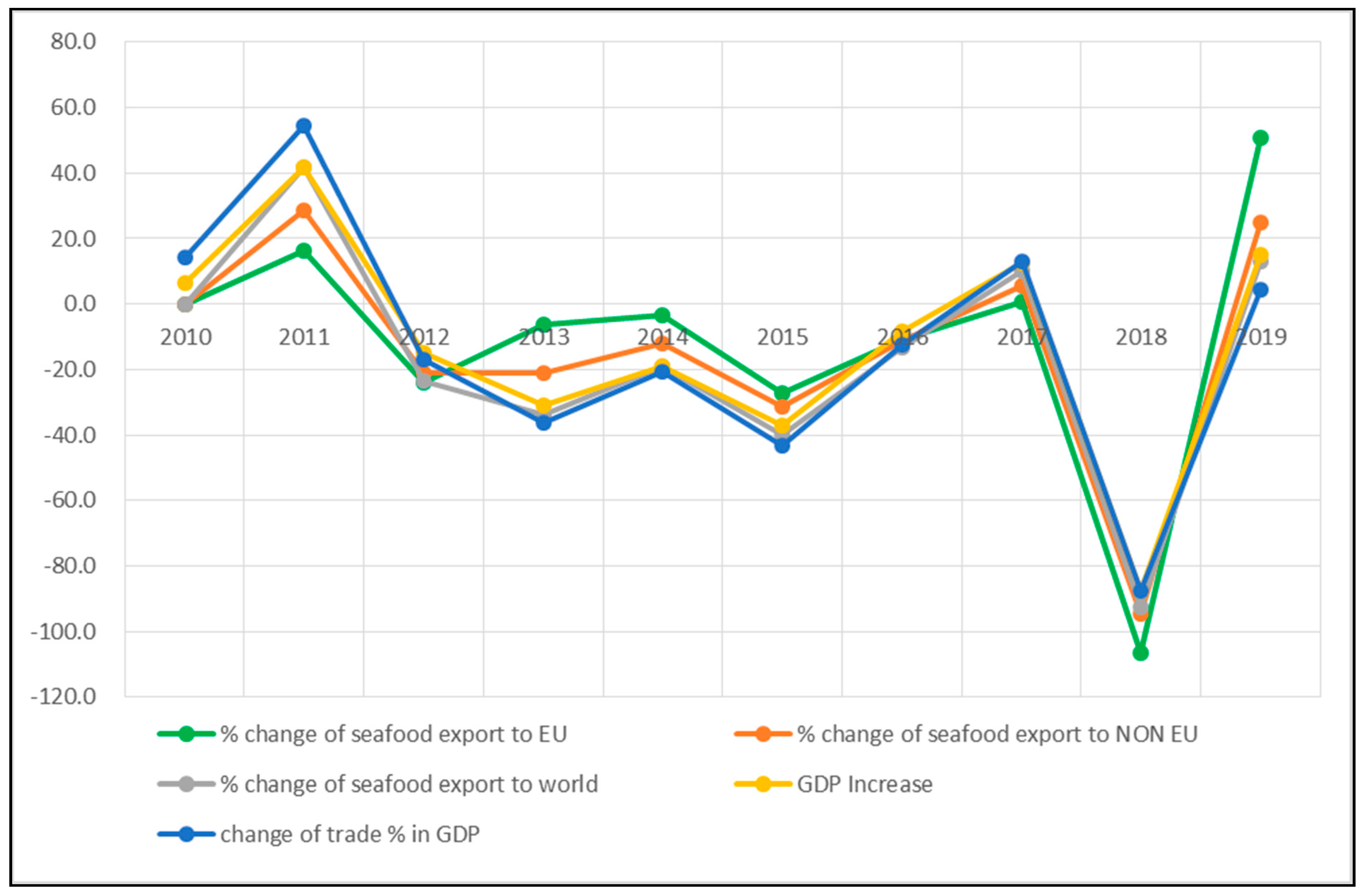

| Year Category | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment in agriculture | −0.46 | 6.30 | 2.71 | 0.70 | −0.29 | −6.47 | −1.19 | 4.71 | 5.51 | 0.12 |

| Unemployment | 0.622 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.489 | 0.576 | 0.597 | 0.688 | 0.83 | 0.766 | 0.754 |

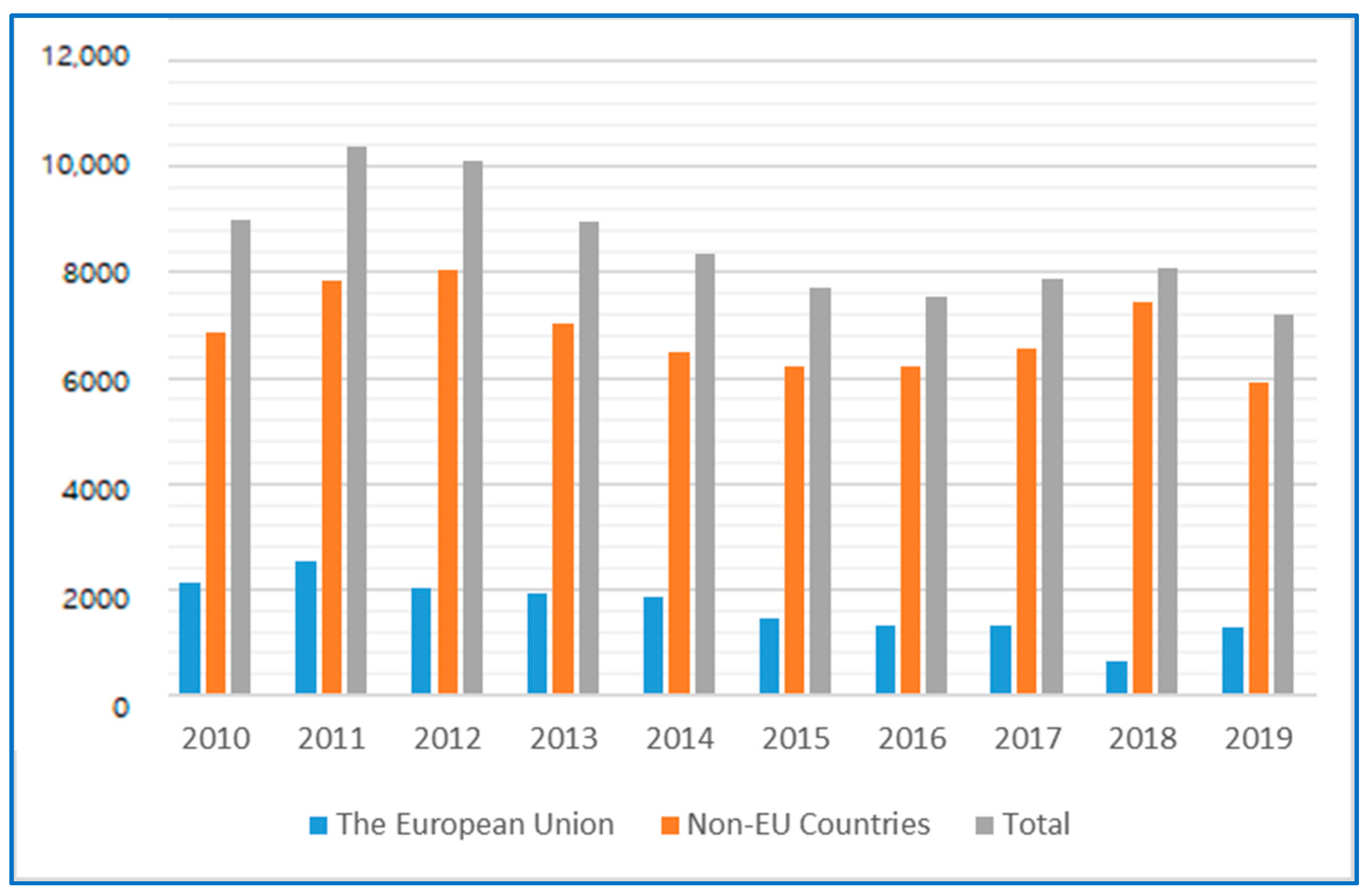

| Year Destination | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The European Union | 2120 | 2529 | 2043 | 1922 | 1856 | 1459 | 1315 | 1322 | 640 | 1296 |

| Non-EU Countries | 6865 | 7840 | 8063 | 7034 | 6495 | 6239 | 6219 | 6559 | 7433 | 5911 |

| Total | 8.99 | 10.36 | 10.10 | 8.96 | 8.36 | 7.70 | 7.53 | 7.88 | 8.073 | 7.21 |

| % of EU | 24% | 24% | 20% | 21% | 22% | 19% | 17% | 17% | 8% | 18% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wongrak, G.; Hur, N.; Pyo, I.; Kim, J. The Impact of the EU IUU Regulation on the Sustainability of the Thai Fishing Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126814

Wongrak G, Hur N, Pyo I, Kim J. The Impact of the EU IUU Regulation on the Sustainability of the Thai Fishing Industry. Sustainability. 2021; 13(12):6814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126814

Chicago/Turabian StyleWongrak, Garnchanok, Nany Hur, Insoo Pyo, and Jungsuk Kim. 2021. "The Impact of the EU IUU Regulation on the Sustainability of the Thai Fishing Industry" Sustainability 13, no. 12: 6814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126814

APA StyleWongrak, G., Hur, N., Pyo, I., & Kim, J. (2021). The Impact of the EU IUU Regulation on the Sustainability of the Thai Fishing Industry. Sustainability, 13(12), 6814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126814