Abstract

Cooperative organizations try to balance economic viability and corporate social responsibility (CSR) management through strategic policies that involve dialogue, participation, and engagement with stakeholders. To measure the impact of CSR management, the electricity sector implements monitoring processes and models, such as the sustainability reporting standards of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), which measure contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations 2030 Agenda. This research analyses the strategic management of CSR in the 28 electric cooperatives that market electricity in Spain with the aim of determining their level of commitment to CSR and stakeholder participation in their corporate policies. The analysis is based on the descriptive-exploratory study of the whole population of electric cooperatives. The results indicate that the CSR management of most electric cooperatives is still in an emerging stage within the Value Curve. Importantly, there is a significant percentage of cooperatives that have already advanced towards the consolidating and institutionalized stages. However, most of these social-economy organizations are not developing programs that link their CSR strategies with their priority SDGs and sustainability as a commitment to their community.

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, the activities carried out by all kinds of organizations have had decisive social, economic, and environmental impacts in the communities where they operate. Corporate social responsibility (CSR), as an approach developed to respond to the increasing interdependence between companies and their social context, can help organizations balance their multidirectional relationships with stakeholders. In this sense, it can be argued that globalization and technological changes are causing a real social transformation that in turn accelerates the evolution of the endogenous and exogenous systemic factors that connect companies with their context [1]. The influence organizations have on their environment has led stakeholders to increasingly demand more information and consideration on the design and development of those strategic corporate policies that may affect them as a social group [2,3].

CSR has been managed according to different regulations, including legislation and guidelines set by international bodies, such as the European Commission, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), United Nations (UN), the International Labor Organization (ILO), the Institute of Social and Ethical Accountability (ISEA), the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), and the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Moreover, since the late 20th century and, fundamentally, since the first decade of the 21st century, business organizations with high social impact have shown an increased interest in sharing their CSR initiatives through conveniently verified sustainability reports and balances [4,5].

Corporate behavior, stakeholder participation in CSR management based on issue identification, and an integrated communication strategy are three fundamental premises to solidify a positive reputation, based ethics, and responsible advocacy [6,7,8]. The inherent complexity and challenges of relationship management highlight the need to implement and improve corporate communication channels to achieve strategic goals.

Business, associative, mutual-benefit, and cooperative organizations generate internal and external conflicts with their stakeholders through their activity, competitiveness, and goal achievement. Responsible relationship management that seeks to maintain a balance between an organization and its stakeholders in the economic, human rights, labor, environmental, ethical, and social spheres should include stakeholders’ environmental, social, and good governance expectations in the organization’s policies as a strategic system [9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

CSR, therefore, stands as an essential factor to guarantee competitiveness and growth [16,17,18,19]. Thus, advocates of CSR (regulators, investors, and society itself) demand business management models that consider ethical, social, and environmental aspects in strategic decision-making and in the configuration of corporate organizational structures [20].

In this sense, cooperatives, as social economy companies, are founded on participatory and social principles, which are preserved and updated, taking as reference the values defended by the International Cooperative Alliance and the regulations and guidelines established by regulatory and legislative bodies [4,5]. The legal nature of cooperatives is fully identified with the basic principles of CSR [21], as they integrate these attributes into their corporate identity and try to balance economic viability with stakeholder dialogue and participation in their business models.

Renewable energy cooperatives are well established in European countries such as Denmark, Holland, Belgium, Germany, Austria, northern Italy, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and France [22], forming a network of 1900 cooperatives actively involved in the energy transition. However, in Spain and southern Italy, these cooperatives are still in an emerging phase. Their energy offer to consumers is based on values such as social cohesion, democratic participation, and the promotion of clean energy and responsible consumption. They are helping to alleviate a problem of a social, economic, and environmental nature [23,24].

This descriptive and exploratory research centers on the analysis of strategic management of CSR (models, regulations, legislation, and guidelines), Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and stakeholder participation in CSR management in Spanish electric cooperatives. This theoretical framework allowed us to analyze the CSR management and contribution to the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda of 28 Spanish electric cooperatives. The study was guided by three research objectives: first, to assess the corporate governance of the cooperatives, based on their degree of CSR commitment and the production of CSR reports; second, to evaluate stakeholder engagement in the cooperatives’ strategic CSR management and their social and environmental commitment with the community; and third, to confirm cooperatives’ degree of knowledge and contribution to the targets associated to SDG 7 (affordable and green energy) and SDG 13 (climate action), which are priority goals for the electricity sector. These general objectives involve the following specific objectives: evaluate the cooperatives’ commitment to CSR culture and management; identify and evaluate the use of CSR and PR management policies, procedures, and standards; evaluate the level of stakeholder engagement in CSR development; evaluate the inclusion of stakeholder expectations in the definition of key processes; identify stakeholder commitment and partnerships arising from CSR policies in the five phases of the Value Curve; and identify links between CSR policy development and SDG 7 and SDG 13.

2. Theoretical Framework

Organizations’ constant adaptation to their environment should include learning how to predict and respond in a credible way to society’s changing perceptions on specific societal issues that affect their activities. As Zadek [25] points out, this task can be overwhelming given the complexity and volatility of societal issues and the difficulty to define the implicit responsibilities of organizations in certain societal problems.

To properly manage conflicts of interest and society’s expectations, good corporate governance requires constant learning of the standardized processes of CSR management, implementation, and communication [26]. Moving from a reactive approach, based on risk and loss of reputation, to an approach that responds to the current sustainability challenges of the electric cooperative sector requires a major change of perspective that would enable progress to be made towards the consolidation of CSR in this sector. Thus, CSR has become an essential strategy to manage conflict reduction, stakeholder engagement, and organizational reputation [27].

The literature review reveals that authors such as Ingenhoff and Marschlich [28] and Ozdora, Ferguson, and Duman [29] identify the intrinsic features of CSR and its integration into PR programs and remark that many of the negative perceptions of CSR activities, which generate skepticism, come precisely from their association with relational strategies that were implemented by organizations exclusively for utilitarian and commercial purposes [30]). These strategies only aimed to clean the public image of corporations to maximize economic benefits.

However, in contrast to this view, there is a school of thought in corporate governance [1,27] that postulates that the social function of any organization inherently entails responsibility for the impact of its actions, decisions, strategic policies, and, therefore, corporate behavior.

2.1. Strategic Management of CSR: Models, Regulations, Legislation and Guidelines

The study of CSR as a philosophy of corporate governance involves different approaches that explain how the interaction between organizations and their social context is triggered by the consequences generated on shareholders and stakeholders [31,32,33]. Many interdisciplinary studies have analyzed the relationships between organizations and their stakeholders, the ethical, philanthropic, normative, economic, social, and environmental aspects of corporate actions, the longitudinal dimension in the implementation of different stages of CSR models as well as their measurement and impact on the creation of corporate value and reputation [16,28,34,35,36,37,38,39].

Among the CSR models that have been revised [20,32,38,40,41,42,43,44,45], Zadek’s civil learning tool [43,44] is of great interest to this research, as it helps companies to identify where they fall on a specific societal issue and to determine how they can develop and position their future business strategies while maintaining a balanced relationship with stakeholders. Based on the contributions made by Zadek and other authors, this article proposes a business management model that integrates ethical, social, and environmental aspects in decision-making processes, as well as the main sustainability challenges identified in a given sector of economic activity (Figure 1).

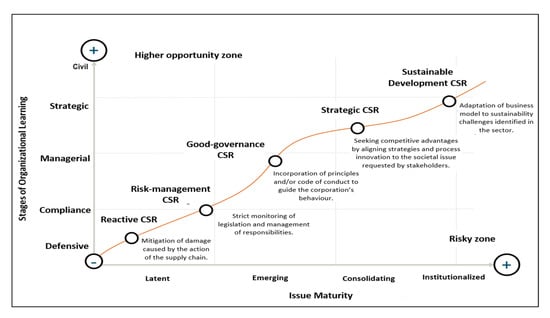

Figure 1.

Value Curve of corporate social responsibility (CSR; evolution by stages). Source: Authors’ own creation based on Ozdora, Ferguson, and Duman [29]; Visser [38]; Zadek [43,44]; Estrategia de la RSC de las empresas españolas [45] and Visser and Courtice [46].

This model is represented in a graph that allows a two-dimensional analysis of CSR management: the stages of organizational learning (y-axis) and the stages of issue maturity (x-axis). The axis that represents organizational learning in CSR management is an iterative process in which progress can be gradual in short and medium terms. This process is characterized, based on the evolution of different stages, by a purely defensive performance; strict compliance with regulations, legislation, and guidelines; operational management; strategic management; and civic engagement in the identification of priority issues that must be addressed through CSR. With regard to the second axis, the stages of maturity of societal issues, as organizations move from left to right (from latent and emerging to consolidating and institutionalized stages), the five stages of the Value Curve materialize: reactive CSR, risk-management CSR, good-governance CSR, strategic CSR, and sustainable development CSR.

In the first stage (reactive CSR), the organization only reacts to conflict situations with stakeholders that require a corporate response; in the second stage (risk-management CSR), organizations fully assume and implement existing CSR regulations and guidelines established by governmental and non-governmental bodies; in the third stage, which represents good governance, standardized CSR models are implemented based on the organization’s degree of voluntary commitment; in the fourth stage CSR becomes strategic through the consideration of stakeholders in the identification of issues that directly affect them and though the reporting of actions over various communication channels; in the fifth stage, sustainable development, the corporate strategy achieves maximum efficiency through the integration, into the organization’s management systems, of relevant issues derived from the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) set in the United Nations 2030 Agenda (2015), as well as the fulfillment of associated targets. This stage is characterized by the active engagement of stakeholders in the strategic process of CSR.

Table 1 presents the most relevant international guidelines, standards, and regulatory instruments for measuring and reporting on social responsibility and sustainability management, as well as the classification of SDGs set by the United Nations as a global corporate strategy.

Table 1.

International CSR guidelines, standards, and regulations.

Of these CSR guidelines, standards, and regulations, the integrated reporting (IR) [48], the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) [49] stand out because they mark a milestone in corporate reporting in a context based on sustainability and stakeholder engagement.

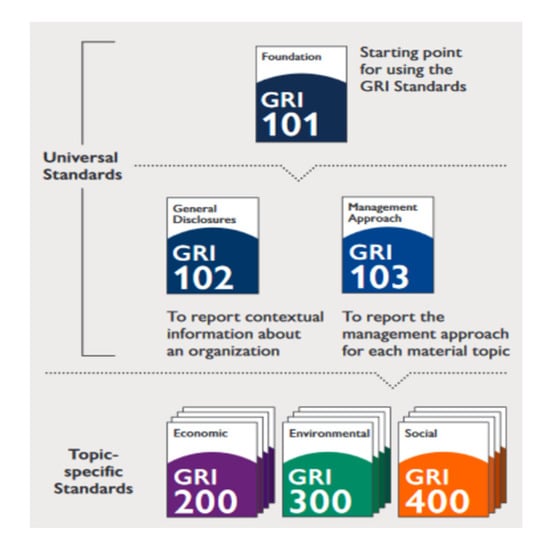

Sustainability and community engagement reporting, promoted by the GRI standards, is one of the key actions for any organization. The public disclosure of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) actions has direct impacts on the financial value of organizations, depending on their (positive and negative) contributions to SDGs [49]. The GRI Standards are divided into two large groups: universal and topic-specific, as shown in Figure 2 and Table 2.

Figure 2.

Groups of GRI standards. Source: Global Reporting Initiative [50].

Table 2.

Development of topic-specific standards. Source: Global Reporting Initiative [50].

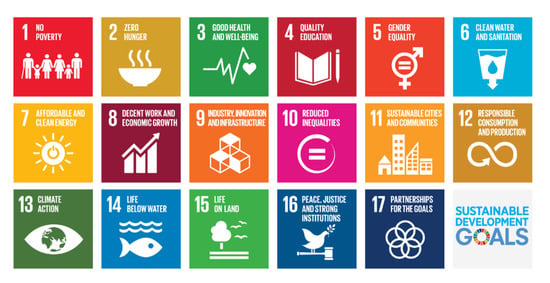

Moreover, following the Brundtland report [51], which defined for the first time the concept of sustainable development, the Rio de Janeiro Summit [52], the UN Global Compact announced at the Davos World Economic Forum [53], and the agreement reached at the Rio+20 conference [54], the United Nations General Assembly incorporated 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) into the 2030 Agenda [55]. These SDGs (Figure 3) are materialized into 169 targets that are classified in three dimensions (economic, social, and environmental) [56], following the approach of the aforementioned international standards.

Figure 3.

Sustainable Development Goals. Source: Sustainable Development Goals [55].

This document sets out, for the first time, universally applicable and contrastable common goals that seek to guide collective global action during the 2015–2030 period in the adoption of measures for the management of the world’s great challenges based on specific goals and targets.

The UN considers that the implementation of the 2030 Agenda requires the intense participation and engagement of governments, the private sector (microenterprises, multinational companies, and cooperatives), and civil society. In addition, the UN conceives organizations as key players in achieving the SDGs, both locally and internationally [57,58]. This initiative urges organizations to adopt a set of universal principles on human rights, labor rights, the environment, and the fight against corruption, through a voluntary commitment to social responsibility and ethics, as reflected in the SDG Compass Guide for business action on the SDGs [59].

2.2. CSR and SDGs in Spanish Electric Cooperatives

Cooperative societies are organizations based on the values, principles, and foundations of CSR. They incorporate the collective interests of the local community into their corporate policies and respond to the problems, needs, and expectations of their stakeholders.

Multiple authors, such as Haro del Rosario, Benítez-Sánchez, and Caba-Pérez [60]; Mochales-González [20]; Mozas-Moral and Puentes-Poyatos [4]; Server-Izquierdo and Lajara-Camilleri [14]; Torres-Pérez [5]; and Vargas-Sánchez and Vaca-Acosta [21], identify a similarity between cooperativism and CSR when they allude to the identity of such legal organizations. According to Carroll [40], these authors point out that the main attributes of cooperatives are their economic, social, and environmental balance, their compliance with national and international legislation, their business ethics, their fulfillment of stakeholder needs in a balanced way, and transparency.

The engagement of cooperative organizations in ethical, social, economic, and environmental issues derives from the relevance given, in the current context, to sustainable development as the central axis of the cooperative model, represented in stage 5 of Zadek’s Value Curve [29,38,43,44,46]. This stage responds to the new social and environmental expectations of a globalized society, which is much more informed and involved in the consequences generated by social organizations in their context of proximity.

In Spain, as in other emerging and developed countries, specific guidelines and regulations have been established as references for the private sector to integrate strategic CSR policies into their corporate programs (Table 3).

Table 3.

National CSR guidelines, standards, and regulations in Spain.

The liberalization of the electric market in Spain occurred gradually [61], starting in 1997 with the promulgation of the Electricity Sector Law [62], which responded to the guidelines set by the European Union. The Community guidelines were geared towards the separation of competition activities (power generation and retail) from regulated activities (transmission and distribution). This process culminated in 2009, when consumers were granted freedom to choose electric power suppliers (retailers), regardless of their geographical location and the electric connection network (distribution companies).

According to the National Commission on Markets and Competition (CNMC) of Spain [63], as of 3 January 2021, there are 956 companies operating in the Spanish electricity market: 623 retailers and 333 distributors. Of all of them, only 28 are cooperatives: 17 distribute and market electricity (with legally differentiated companies), while 11 focus on retail (Table 4). Electric cooperatives, as a corporate model based on sustainable energy management that guarantees the supply of electricity to partners and customers at a cost below the market average, currently represent 2.8% of the structure of the Spanish electricity market.

Table 4.

Electricity retail cooperatives.

As mentioned, the 17 SDGs set by the United Nations Division for Sustainable Development Goals [64] and their corresponding targets condition the strategic management of CSR in a completely global social, political, and economic context [45]. Two of the 17 SDGs are particularly relevant for the good governance of sustainable development in the electric cooperative sector: SDG 7, which refers to the need to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all; and SDG 13, which calls on the international community to take urgent action to combat climate change and its effects.

The social perception of the cooperatives’ commitment to the SDGs and their targets depend on the CSR actions they carry out and the knowledge they generate about their corporate strategy for the benefit of their stakeholders and society in general. For electric cooperatives to position themselves according to their social identity, it is not enough to just exploit their legal corporate nature and implement standardized models to evaluate integrated CSR management through the GRI Standards [4,5,60,65,66]. It is also essential for cooperatives to design and implement integrated communication management models with stakeholders, establishing a system of permanent dialogue that enables more positive engagement, a higher level of trust, and, in turn, greater competitive advantage based on market positioning [67].

2.3. CSR Management with Stakeholders in Electric Cooperatives

The integrated communication strategies of electric cooperatives contribute to building trust and credibility with stakeholders. Authors such as Dopazo-Fraguío [68]; Orozco-Toro and Ferré-Pavia [69]; Falcón Pérez [24]; and Arenas-Torres, Bustamante-Ubilla, and Campos-Troncoso [70] have analyzed, from a multidisciplinary perspective, different relational processes to manage dialogue, commitment, and co-orientation between organizations and stakeholders through CSR, from the perspective of stakeholder theory, circular economy theory, and network theory [30,71,72]. Following the implementation of standardized reporting monitoring models, CSR strategies should respond to the corporative goals defined in the different stages of the Value Curve.

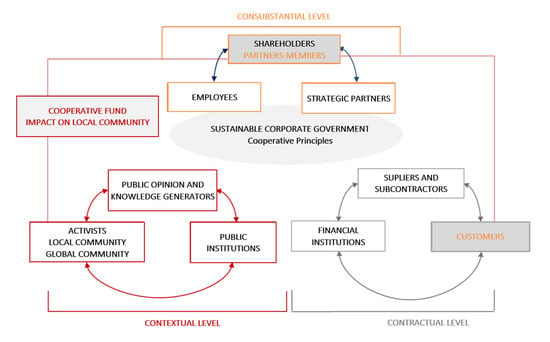

A strategic process focused on stakeholders allows organizations to analyze the importance of these groups in achieving the corporate targets linked to sustainability [45]. The stakeholder map of electric cooperatives includes different groups, organizations, and institutions that are integrated into three situational levels [30,71,72]: consubstantial, contextual, and contractual (Figure 4). The consubstantial level, which is governed by the principles of cooperative and sustainable governance, has a direct impact on the contextual level through the cooperative fund for social actions in the local community.

Figure 4.

Stakeholder classification in electric cooperatives. Source: Authors’ own creation based on Fundación Entorno, IESE, and PWC [73] and Torres-Pérez [5].

As sustainable organizations, electric cooperatives integrate into their strategies the expectations, needs, and demands of their diverse stakeholders with whom they establish enabling, functional (input and output), normative, or diffused links (enabling links provide organizations with the authorization they need to develop their activities and control the resources that enable their existence and survival in their environment. Functional links allow organizations to develop input activities with employees and suppliers and output activities with clients/consumers: they represent the connection between supply and demand. These links allow organizations to reach their strategic corporate objectives through work and permanent collaboration with diverse groups. Normative links refer to those relationships established between organizations that share common values or the same strategic interests. Diffused links are established when the organization has specific consequences on external groups or stakeholders that are not permanently linked to the organization) to maintain balanced relationships, and generate a positive image that contributes to a solid reputation [30,74]. In this type of organizations, there is a complex stakeholder category due to the type of link that is generated between a cooperative and its shareholders or cooperative partners: they establish an enabling relationship (at the consubstantial level) and functional (output) relationship (at the contractual level) because they are also customers [5].

There are different mechanisms to communicate CSR actions to stakeholders, as noted by Orozco-Toro and Ferré-Pavia [69]; Stocker, de-Arruda, de-Mascena, and Boaventura [75]; Hu, Zhang and Yan [76]; and Guillamon-Saorin, Kapelko, and Stefanou [77] among others. Organizations use various formats to translate their CSR results into a report, mainly the annual memoir (or sustainability report) and the social balance resulting from the standard compliance audit. Through corporate websites, social networks, and multimedia platforms, cooperative organizations generate content for their stakeholders [78,79] as an extension of the information included in their annual reports and balances.

3. Methods

A descriptive and exploratory study was carried out in 2019 (January to December) to analyze the CSR management and contribution to the UN 2030 Agenda [55] of the 28 Spanish electric cooperatives based on the following key aspects: corporate governance, strategic CSR management, and social and environmental initiatives.

The methodological instrument used to achieve the research objectives set in the introduction is the SDG Compass tool [80], which associates the GRI Indicators (Global Reporting Initiative) with the targets associated with each SDG (Table 5 and Table 6), as shown below.

Table 5.

Targets of the 2030 Agenda for SDG 7 and their association with GRI indicators.

Table 6.

Targets of the 2030 Agenda for SDG 13 and their association with GRI indicators.

A semi-structured questionnaire was designed and implemented as a methodological tool to evaluate five key aspects of the strategic management of CSR in electric cooperative organizations: corporate governance, policies and strategies, stakeholder engagement, processes, and commitments and partnerships.

The structure of the questionnaire is based on the GRI indicators of the SDG Compass Guide for business action [49]. Such indicators are used as verified parameters in the CSR practices of the leading Spanish power companies and have been documented in their sustainability reports. These indicators correspond to five steps: understanding the SDGs; defining priorities to benefit from the business opportunities and reduce risks; setting sustainable development goals and targets to foster shared priorities, corporate commitment, and drive performance across the organization; integrating sustainability into the core business and governance of companies by engaging in partnerships with organizations in their sector, public administrations, and civil society organizations; and finally, reporting and communicating sustainable development as the highest level of the CSR Value Curve.

The questionnaire (Appendix A) consisted of five sections (26 questions) (Table 7) on the aforementioned five key aspects that measured the degree of standardization in CSR management in electrical cooperatives and the integration of these policies into the global corporate strategy.

Table 7.

Questionnaire structure: sections and justification according to general and specific objectives.

On the other hand, the model of the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM) [81] allowed us to set the different multiple response options. It represents the constant adaptation of the goals and internal processes of organizations to the demands of their stakeholders and environment. The REDER scheme for continuous improvement of the EFQM Model introduces a systematized approach to develop a system of organizational control and learning on sustainable management, the review of the different results that are established as goals, and the processes to achieve them. This questionnaire was validated by a panel of experts from the cooperative sector during June 2019 and was subsequently distributed across the 28 Spanish electric cooperatives via email. It had a response level of 96% among managers and directives in charge of CSR management in their respective organizations.

4. Results

The first result of this research is that many electric cooperatives are aware of the relevance of CSR as an attribute linked to corporate identity. This first level is evolving inclusively to consolidate, eventually, the commitment to the continuous improvement of CSR and sustainability management (level 5).

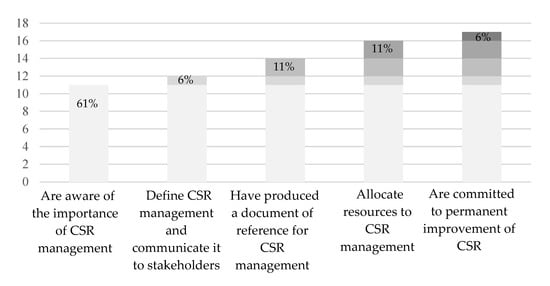

As Figure 5 shows, 61% of the cooperatives have assumed CSR management as a main intangible asset. In addition, 6% of the cooperatives informally define their CSR strategy and communicate it to stakeholders through various channels; 11% have also produced a reference document to reflect their annual CSR strategy, and the same percentage allocates economic resources for the management of their CSR program. The last level, represented as the solid commitment to continuous improvement, is only reached by 6% of all the cooperatives analyzed.

Figure 5.

Governance. Degree of commitment to CSR.

Thus, we can see how CSR is being managed by corporate governments following different international regulations, laws, and guidelines, as well as diverse ethical, economic, social, and environmental issues derived from cooperatives strategies. The implementation of CSR models and the evaluation of their impact on the creation of corporate value and reputation allows organizations to identify priorities to implement future business strategies aimed at balancing stakeholders’ needs.

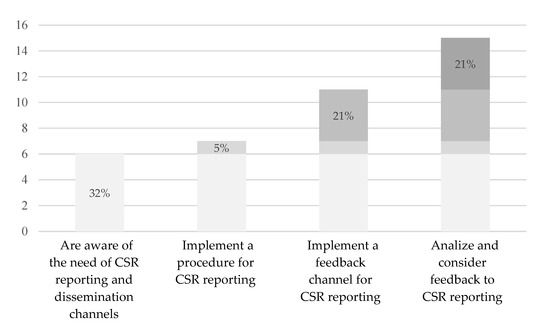

In this context, the level of development in CSR reporting is relevant in electric cooperatives. As we can see in Figure 6, only 32% of the organizations are aware of the need to develop a CSR report and of implementing the appropriate channels to disseminate the CSR actions developed over a given period. However, only 5% of the cooperatives have implemented a formal management system for CSR reporting, following the guidelines of leading bodies, which would allow the development of standardized and verified procedures to prepare the report. 21% of cooperatives have implemented channels to get stakeholders’ feedback on their CSR initiatives. The same percentage of cooperative organizations (21%) analyze and evaluate stakeholders’ feedback. Accordingly, the data resulting from this two-way process influence future strategies linked to the cooperatives’ governance and social and environmental values.

Figure 6.

Governance. Degree of development in CSR reporting.

In the preparation of corporate non-financial information reports, the most common instruments for power cooperatives in a context based on sustainability and stakeholder engagement are the Integrated Reporting (IR; 2011), the United Nations 2030 Agenda (2015), and the GRI (Global Reporting Initiative) standards (2016, 2018). Consequently, sustainability reports represent one of the most important strategic actions for any organization since the disclosure of environmental, social, and governance impacts to sustainable development have a direct impact on its financial value.

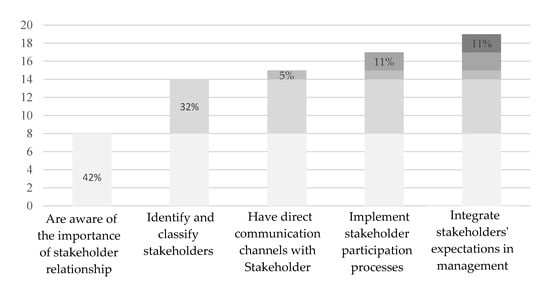

With regard to the relationships that cooperatives have established with their stakeholders, Figure 7 shows that 42% of the surveyed organizations claim to be aware of the desirability of maintaining a balanced relationship with stakeholders. In this sense, it is observed that only 32% of the cooperative organizations have mapped, identified, and classified stakeholders and shareholders as well as the type of relationships established with them. Only 5% of cooperatives claim to have direct, two-way communication channels with stakeholders; 11% claim to implement stakeholder participation processes in their CSR management; and another 11% claim to integrate stakeholders’ expectations within their corporate strategy.

Figure 7.

Strategic PR management. Stakeholder engagement.

The CSR strategies of electric cooperatives contribute to the generation of trust and credibility among stakeholders through dialogue, commitment, and co-orientation. As we can see, the implementation of standardized CSR reporting and monitoring models responds to the corporate objectives identified in the different stages of the Value Curve, proposed in Section 2.1. In this sense, the cooperatives’ strategic engagement with stakeholders allows us to analyze the relevance of the latter in the achievement of corporate sustainability-related objectives as the last phase of the Curve.

With regard to the degree of commitment to the local community, characterized primarily by engagement with social and environmental values, there is a significant difference.

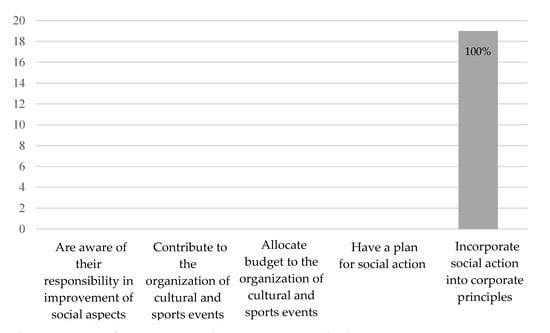

As shown in Figure 8, the identity of cooperatives as social-economy entities imposes a high level of commitment to social values. The corporate principles and values of these organizations assume the responsibility to improve the conditions of the local community as a context of proximity where they develop their economic or business activities. Consequently, both the corporate culture and behavior of electric cooperatives result in a permanent social action that is part of their strategic functions in their relationship with shareholders and stakeholders, as we can see at the last level.

Figure 8.

Degree of commitment to the community (social values).

These results indicate that power cooperatives have carried out responsible management of stakeholder engagement since they include their social and governance expectations in corporate policies as strategic systems.

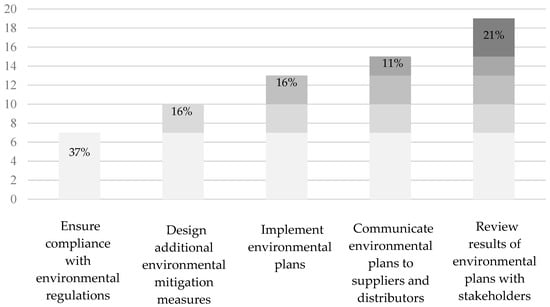

However, if we focus on the degree of commitment to environmental values (Figure 9), we can see that 37% of cooperatives only ensure compliance with environmental regulations without making a greater commitment. Only 16% of organizations have designed complementary measures to reduce their internal and external environmental impacts and have implemented environmental plans. Meanwhile, 11% have communicated their environmental programs to their suppliers and distributors. Finally, at the highest level, it is noted that 21% of electric cooperatives have reviewed the results of their respective strategic environmental plans with their stakeholders.

Figure 9.

Degree of commitment to the community (environmental values).

These results confirm the existing conflict in the environmental field on the part of electric cooperatives. In the light of the results, it is necessary for cooperatives to manage the environmental expectations of society and stakeholders much more responsibly since this strategic CSR policy has a significant influence on their sustainable development, the achievement of their priority SDGs, their competitiveness, financial value, and corporate reputation.

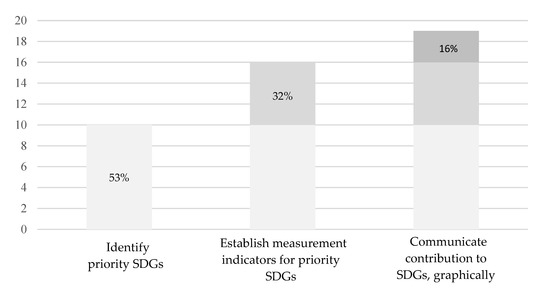

Figure 10 shows the cooperatives’ degree of knowledge and commitment to SDG 7 (affordable and green energy) and SDG 13 (climate action). As we can see, 53% of the cooperatives have identified both SDGs within their CSR strategy, and 32% have implemented standardized management systems, such as reporting, to measure the GRI indicators linked to the targets set for each of the two SDGs. However, only 16% of the organizations communicate their results or contributions to SDGs to their stakeholders through responsibility or sustainability reports, social management balances, corporate websites, social networks, and multimedia platforms.

Figure 10.

Degree of knowledge and commitment to priority SDGs.

The use of all of these communication platforms and resources would guarantee the cooperatives’ dissemination of their CSR report to stakeholders. The lack of effective communication processes undoubtedly represents an opportunity cost for the generation of content aimed at society and stakeholders since the corporate website, blogs, social networks, and multimedia platforms allow cooperative organizations to amplify and highlight the importance of the information included in their annual reports and balances.

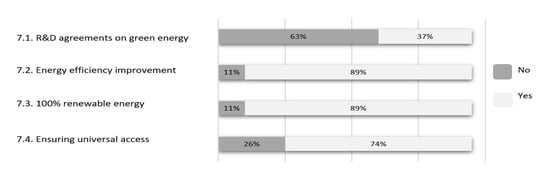

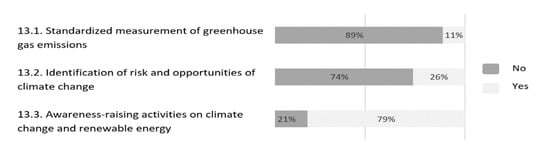

In this sense, and to delve into the results, Figure 11 and Figure 12 analyze the contribution of electric cooperatives to the priority SDGs in the sector through the development of certain actions initiatives linked to the GRI indicators (Table 5 and Table 6), which are included in each of the targets of SDG 7 and 13.

Figure 11.

Degree of contribution to SDG 7: Affordable and green energy.

Figure 12.

Degree of contribution to SDG 13: Climate Action.

Regarding the contribution to SDG 7, only 37% of the cooperatives have made significant investments to implement research agreements and strategic partnerships with R&D companies. Importantly, 89% of organizations have implemented network and service innovations to improve energy efficiency and have guaranteed the 100% renewable origin of electricity, certified by the National Commission on Markets and Competition (CNMC). On the other hand, 74% of cooperatives have established specific actions in the electricity grid, service supply, or the price scale to ensure universal access to affordable and green energy.

Therefore, based on the GRI indicators (Figure 11), there is a remarkably greater commitment to SDG 7 in comparison to the actions carried out by electric cooperatives with respect to SDG 13 (Figure 12), in which only climate change and renewable energy awareness-raising activities stand out (in 79% of cooperatives). Standardized greenhouse gas emission measurement and identification of risks and opportunities to develop efficient climate change policies, which are present in 11% and 26% of the analyzed organizations, respectively, show the dissonance between the projection of a public image linked to SDG 13 (Climate Action) and the cooperatives’ own identity, which is based, among other things, on environmental values but does not translate into a corporate behavior consistent with the other priority SDG.

Electric cooperatives, as social-economy companies, are based on participatory and social principles that are present in their corporate identity, as demonstrated by their degree of commitment to the community. These organizations have a high impact on society, which leads regulators, investors, and society itself to demand the implementation of strategic CSR programs that respond to standardized management, monitoring, and evaluation models and are integrated within corporate strategies.

The five sets of items included in the questionnaire to analyze corporate governance, policies and strategies, stakeholder engagement, processes and commitments, and partnerships, together with the GRI indicators that provide information on CSR actions and their contribution to the targets of priority SDGs for the sector, have allowed us to determine the electric cooperatives’ degree of commitment to CSR based on the progressive stages of the Value Curve [29,38,43,44,46]. In this regard, while electric cooperatives are taking enough action to materialize SDG 7 (affordable and green energy), the development of activities to consolidate SDG 13 (climate actions) and their integration into the CSR strategy are still very scarce.

The research indicates that most electric cooperatives (61%) are positioned in stage 3 of the Value Curve (good governance CSR). This stage is characterized by the relevance the organization gives to the principles and codes of conduct governing its behavior and their connection with strategic CSR policies (Figure 5) and by the identification and classification of stakeholders (42%), which enables the analysis of engagement with the organization (Figure 7). These results derive from sections 1, 2, and 3 of the questionnaire.

However, the fact that 11% of the organizations facilitate the participation of stakeholders in CSR management and integrate their social, economic, and environmental expectations (Figure 6) allows us to infer that electric cooperatives are currently making some progress within the Value Curve, going from stage 3 to 4 (Strategic CSR), as shown by the results obtained from Section 4 of the questionnaire.

In addition, more than half of the organizations (53%) identify SDGs 7 and 13 as priorities for the sector (Figure 10); while 32% establish standardized measurement indicators and 16% also disseminate their results, setting a clear trend towards stage 5 (Sustainable Development CSR), as shown by the results derived from Section 5 of the questionnaire.

Consequently, and although most electric cooperatives are in the emerging stage of issue maturity (between stages 2 and 3 of the Value Curve, risk management, and good governance), there is a significant percentage that is already in the consolidation and institutionalization stages of the Value Curve (between stages 3 and 4, and stage 5, respectively). However, and despite this evolution, the CSR strategies of most of these organizations do not include measurement and dissemination indicators for their priority SDGs (Figure 10). Thus, the progression that begins to occur towards stage 5 of the Value Curve (Sustainable Development CSR), linked to SDGs, is not present in the corporate documents used to report social responsibility, sustainability, economic activities, and non-financial information. This circumstance, according to Morsing and Schultz [82] and McKie and Heath (2016) [1], implies an opportunity cost for those electric cooperatives that have not yet implemented CSR strategies that integrate SDG 7 (affordable and green energy) and SDG 13 (climate action). The absence of integrated CSR programs that allow cooperatives to generate trust and credibility and strengthen stakeholders’ engagement and participation is an important obstacle to reach stage 5 of the Value Curve of CSR. This stage of sustainable development would allow for greater profitability of the corporate strategy derived from the goals of the SDGs into the management systems and processes of electric cooperatives.

5. Conclusions and Future Lines of Research

The Value Curve model we proposed in the theoretical framework can help electric cooperatives identify their stage of CSR development. Accordingly, organizations that want to advance in the implementation and improvement of their CSR must plan and implement strategies that integrate the social and environmental concerns of stakeholders and society in general.

Advancing in the CSR Value Curve requires a change of mindset that involves abandoning the idea of CSR management as an exclusive effort to mitigate risks in a reactive way. This change involves considering a new paradigm that is based on innovation and integrates the social and environmental aspect as an epicenter of the corporate activity of electric cooperatives with the active collaboration of the diversity of stakeholders (Figure 5).

Aligning the CSR strategy with the global corporate strategy generates an unquestionable competitive value that brings mutual benefits for both cooperatives and society. The pragmatic vision set out in this model makes it easier for organizations to know where to move to manage contextual risks and seize opportunities. In this sense, CSR management requires cooperatives to learn to identify conflicts and problems and prioritize those material issues that affect or may influence their business model.

Consequently, reaching the highest level in the CSR value curve for electrical cooperatives can substantially increase their corporate reputation, consolidate their position in the electricity market, reduce reputational risks, develop a social and ecological corporate culture, increase opportunities when tendering for public sector contracts, increase the loyalty of partners-customers, increase employees’ motivation and satisfaction, and strengthen their influence in their context of proximity.

The materiality or degree of relevance of the social issues and expectations to which cooperatives must respond through CSR represents a decisive aspect to minimize strategic risks and take advantage of the opportunities offered by the electric power sector. The diagnosis of risks and opportunities can be the source of new capabilities with which these organizations can learn to effectively engage with an increasingly demanding and competitive market and to generate engagement with their stakeholders. The identification of the material (social and environmental) issues linked to the SDGs and their targets is, therefore, one of the delimitations of this research.

The second limitation of our contribution is the development of comparative research between Spanish and other European electric cooperatives, from a strategic and management approach, since this type of study would allow us to identify and compare, through a SWOT analysis, the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of this sector of economic activity from a much more comprehensive perspective.

The third delimitation of this work is that it has been found that there is a significant difficulty in establishing robust stakeholder communication systems that contribute to the identification of the priority issues that affect or may affect electric cooperatives and to their incorporation into CSR management systems. Thus, we consider that the design of strategic communication models that guarantee feedback from stakeholder communication and management processes would help electric cooperatives move towards stage 5 of the Value Curve, linking sustainable development policies with priority SDGs and their targets in corporate reporting. The dissemination of this process of development in CSR management and its alignment with strategic corporate policies, based on the guidelines of the 2030 Agenda, is one of the most significant and immediate challenges for the electric cooperative sector.

Author Contributions

C.C.-A. and D.I.-A. conceptualized the theme of the paper and collected the data. C.C.-A. wrote the introduction and the literature review of the paper and complemented the discussion. D.I.-A. designed the methodology of the article and drafted the conclusion. C.C.-A. reviewed and edited the research sections of the manuscript. Both contributed equally to the preparation of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the I3CE Research Network Program for University Teaching of the Education Sciences Institute of the University of Alicante (call 2020–21). Ref.: (5230) PRO-TO-COL Inter-University Network of Collaborative Work in Protocol, Event Management, and Institutional Relations (2020–2021).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

QUESTIONNAIRE on Corporate Social Responsibility Strategies in Spanish Electric Cooperatives

Dear participant,

We are carrying out a research project on social responsibility and stakeholder communication in electric cooperatives. We would really appreciate it if you could spend a few minutes of your time answering the following questions regarding CSR management in your organization and its contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The questionnaire consists of a total of 26 questions divided into 5 sections. Answer options go from the lowest to the highest degree of development, taking into account Deming’s PDCA (Plan, Do, Check, Act) continuous improvement cycle. Thus, after the first option, the answers include the values of the previous answers.

Please do not forget to provide the basic information. Thank you in advance for your cooperation.

SECTION A1. Corporate Governance

1. Has management defined the organization’s position on CSR and communicated it?

- Management is aware of the importance of integrating corporate social responsibility actions.

- Management is aware of the importance of CSR, has defined a CSR policy and has communicated it to stakeholders.

- Management has defined its CSR policy, and has a framework document with objectives, goals, and programs in line with its CSR policy.

- Management has a CSR framework document and has allocated resources for the implementation of CSR in organizational management.

- In addition, management is committed to the continuous improvement of the CSR management system.

* Specify whether the organization has any documents to support the management of CSR (fundamental principles/code of conduct/CSR manual, etc.) and name it:

Your answer

2. Does the organization periodically provide accessible, clear, complete, factual, and public information on its performance in economic, social, and environmental terms?

- Management is aware of the need to establish communication mechanisms for CSR reporting.

- Management is aware of the need and ensures that effective CSR communication channels are established and implemented.

- Management, in addition to establishing CSR communication channels, has a procedure to disseminate progress in its CSR management.

- Management encourages stakeholder participation in CSR through its communication channels and collects opinions through surveys or other methods.

- In addition, the organization analyzes the feedback given to its CSR communication for the purposes of continuous improvement.

* Specify whether the organization has any documents related to CSR communication (communication plan/annual reports with social or environmental aspects/sustainability reports, etc.)

Your answer

3. Has the organization analyzed its economic, social, or environmental impacts on its stakeholders and identified its legal responsibilities in economic, social, and environmental matters?

- The organization has a clear management approach to maximize profits in a sustainable way.

- The organization has a clear management approach and has established the necessary control mechanisms and systems to ensure managers meet the established values.

- The organization, in addition to control mechanisms, has established management systems to account for the impact of its decisions.

- Through the previous mechanisms, the organization analyses and evaluates its economic, social, and environmental impacts.

- In addition to the above, the organization assumes and demonstrates a public commitment to information transparency.

* Specify whether the organization has any documents related to good corporate governance (statutes/codes/fundamental principles/definition of values, etc.)

Your answer

SECTION A2. Policies and strategies

4. Does the organization have a Human Resources procedure that ensures the recruitment, maintenance, and training of workers according to objective and non-discriminatory criteria?

- The organization has the right policies to ensure fairness and equality to workers.

- The organization has management policies and mechanisms in place to ensure legal compliance in labor matters.

- The organization has equity and equality policies in place, mechanisms to ensure legal compliance in labor matters, and formalized documents of the systems of remuneration, selection, promotion, working hours, permits, conciliation, etc.

- The organization has perception and performance data and indicators to evaluate and monitor the effectiveness of HR policies described above.

- In addition, the organization aligns HR management plans with its business strategy.

* Specify whether the organization has any plan to support HR management (training plan/social action plan/equality plan/complaint channels, etc.)

Your answer

5. Does the organization engage in the long term with the local community in which it operates, maintaining its production centers there and creating direct and indirect employment?

- The organization has an estimate of its direct and indirect contribution to the local economy.

- Based on the estimation of its contribution, the organization performs one-off actions that promote local employment.

- In addition to these actions, the organization systematically incorporates the local aspect into its purchasing and recruitment processes.

- The organization has indicators to measure its contribution to the development of the local economy.

- The organization analyses the results of the above actions and proposes improvements in its policies to promote local development.

* Specify whether the organization has any documents that describe its local development contribution policies.

Your answer

SECTION A3. Stakeholders

6. Has the organization defined its relationships with stakeholders and integrated their needs and expectations into its management systems?

- Management is aware of the importance of meeting the needs of stakeholders.

- The organization, aware of its importance, has identified and classified its stakeholders.

- The organization, in addition to identifying and classifying stakeholders, has a document that establishes communication channels with its stakeholders.

- The organization has defined, classified, prioritized stakeholders, and has established processes for their participation in relevant corporate aspects.

- In addition, management takes into account stakeholder expectations to define the organization’s strategy.

* Specify whether the organization has any documents to manage its relationship with stakeholders (identification and prioritization/guide or manual for the management of stakeholder engagement/implementation of Standard AA1000), and name it:

Your answer

7. Does the organization carry out social activities through corporate volunteering, promotion of sport and culture, collaboration with NGOs, support for local agents, or others?

- The organization is aware of its responsibility in improving the social aspects of community life.

- The organization contributes to the organization of cultural and sporting events in the local community.

- The organization allocates a specific budget to the promotion of the community’s cultural and sporting events.

- The organization has a plan to channel the promotion and funding of social and cultural initiatives.

- As a result, the organization adopts the principles of improving the social aspects of community life.

* Specify whether the organization has any documents, plans, mechanisms, or foundations that contribute to the promotion of socio-cultural and sports activities in the local community.

Your answer

SECTION A4. Processes

8. Does the organization contribute to the conservation of the environment and the efficient use of natural resources?

- The organization guarantees compliance with environmental regulations.

- The organization has taken steps beyond the legal aspects to reduce external and internal environmental impacts of production.

- The organization has implemented environmental plans, which include measures to prevent and manage environmental risks.

- The organization has also deployed its environmental plans to its suppliers and distributors.

- The organization has reviewed the results of its environmental plans together with its stakeholders to make improvements.

* Specify whether the organization has any management documents or systems that contribute to pollution and climate change prevention or biodiversity preservation (ISO 14001/EMAS/environmental impact studies, etc.).

Your answer

9. Does the organization advise its clients on the responsible use of the products and/or services?

- The organization provides clear, accurate, and truthful information about its products/services on labeling and other technical documents.

- The organization, in addition to labeling and technical documentation, establishes communication channels to answer frequently asked questions, including those related to social, environmental, and after-sales service aspects.

- The organization, in addition to providing clear information, establishes communication channels to disseminate advice for the responsible use of its products or services.

- The organization accepts consumers’ suggestions for improvement via established communication channels.

- In addition to the above, the organization applies suggestions for improvement by introducing social and environmental criteria into its innovation processes.

* Specify whether your organization has a communication channel that helps disclose information to customers about responsible use of its products and services.

Your answer

SECTION A5. Commitments and partnerships.

10. Is the organization aware of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda for global development proposed by the UN?

- No, it is not aware (press “next” button and submit questionnaire).

- Yes, it is aware and has collected information about them.

- Yes, it is aware, has collected information about them, and has shown interest in contributing to their achievement.

- Given this interest, the organization has established a priority plan to contribute to their achievement.

11. Has the organization identified the SDGs that relate the most to the activities it carries out?

- Yes.

- No.

12. Has the organization established indicators to measure its degree of contribution to the achievement of SDGs?

- Yes.

- No.

Section A5.1. Dissemination of SDGs

13. Is there a plan to disseminate the SDGs among employees, for example, through training activities?

- Yes.

- No.

14. Is the information on CSR and sustainability that is presented on corporate channels graphically linked to the SDGs?

- Yes.

- No.

15. Does the organization carry out any volunteer work related to the SDGs?

- Yes.

- No.

Section A5.2. SDG 7: Affordable and clean energy

16. Has the organization established specific network, product, or price development campaigns to facilitate access to the most disadvantaged sectors of the population?

- No.

- Yes, it provides network access to the most disadvantaged sectors.

- Yes, it offers accessible service packages for most disadvantaged groups.

- Yes, it provides access in the most disadvantaged sectors, offers accessible service packages to disadvantaged groups.

- Yes, it combines different network, product, or price actions (social bonds, discounts, deferrals, and payment splits) to promote access to energy to disadvantaged groups.

17. Has the organization carried out preventive actions or improvements to reduce the frequency of power outages?

- It does not apply because the organization does not have its own network.

- No.

- Yes, preventive actions are performed periodically.

- Yes, preventive actions are performed following a plan to reduce the number of interruptions equivalent to the installed capacity (NIEPI indicator).

18. Has the organization carried out preventive actions or improvements to reduce the duration of power outages?

- □

- It does not apply because the organization does not have its own network.

- □

- No.

- □

- Yes, preventive actions are performed periodically.

- □

- Yes, preventive actions are performed following a plan to reduce the average interruption time equivalent to the installed capacity (TIEPI).

19. Has the organization implemented measures to increase the percentage of electricity from renewable sources that are marketed?

- □

- No.

- □

- The percentage of marketed electricity from emissions-free technologies is higher than the previous year.

- □

- The 100% renewable origin of electricity has been certified by the National Commission on Markets and Competition (CNMC).

- □

- The marketing of 100% renewable energy is the purpose of the organization.

20. Has the organization implemented measures to increase energy produced from renewable sources?

- □

- It does not apply because the organization does not generate energy.

- □

- The percentage of renewable origin electricity is higher than the previous year.

- □

- The 100% renewable origin of electricity has been certified by the National Commission on Markets and Competition (CNMC).

- □

- The production and marketing of 100% renewable energy is the purpose of the organization.

21. Has the organization developed an action plan to reduce domestic energy consumption?

- □

- No.

- □

- Improvements have been made to buildings and facilities, and processes to improve energy efficiency have been implemented.

22. Has the organization implemented innovations to increase the energy efficiency of the products and services provided?

- □

- No.

- □

- Yes.

23. Has the organization implemented research agreements (commitments and investments) to provide efficient and sustainable electricity?

- □

- No.

- □

- Yes.

Section A5.3. SDG 13: Climate action

24. Does the organization measure greenhouse gas emissions using standardized indexes and has put measures in place for their reduction?

- □

- No.

- □

- Yes, the organization measures its carbon footprint according to the “GHG Protocol” or the ISO Norm 14064-1.

- □

- In addition to measuring its carbon footprint, the organization has specific policies to curb climate change.

25. Has the organization identified what risks and opportunities related to climate change can cause significant variations in operations, revenue, and costs?

- □

- No.

- □

- Yes, it has done so by using its own indicators.

- □

- Yes, it has done so from the life cycle perspective (ISO/TS 14072:2014).

26. Has the organization provided internal training/awareness-raising courses or carried out outreach activities on the importance of the use of renewable energy to curb climate change?

- □

- No.

- □

- Yes, to internal audiences.

- □

- Yes, to external audiences using its own (web) platforms.

- □

- Yes, to internal and external audiences.

- □

- Yes, there is a plan to raise social awareness on climate change aimed at all stakeholders.

References

- McKie, D.; Heath, R. Public relations as a strategic intelligence for the 21st century: Contexts, controversies, and challenges. Public Relat. Rev. 2016, 42, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M.R.; Porter, M.E. Estrategia y sociedad: El vínculo entre ventaja competitiva y responsabilidad social corporativa. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, K.; Taylor, M. The Handbook of Communication Engagement; Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mozas-Moral, A.; Puentes-Poyatos, R. La responsabilidad social corporativa y sus paralelismos con las sociedades cooperativas. REVESCO 2010, 103, 75–100. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Pérez, F.J. Análisis legal de la implementación de la RSC en las Sociedades Cooperativas. Rev. Jurídica Portucalense 2017, 21, 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Boronat-Navarro, M.; Pérez-Aranda, J.A. Consumers’ perceived corporate social responsibility evaluation and support: The moderating role of consumer information. Tour. Econ. 2019, 25, 613–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidul, H.; Jamilah, H. Ethics in Public Relations and Responsible Advocacy Theory. Malays. J. Commun. Jilid 2017, 33, 147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Lee, H. The Effect of CSR Fit and CSR Authenticity on the Brand Attitude. Sustainability 2020, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.; Jonker, J.; Van Der Heijden, A. Making sense of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 55, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Harjoto, M.A. Corporate governance and firm value: The impact of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 103, 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Harjoto, M.A. The causal effect of corporate governance on corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 106, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, A.B.; Devin, B. Operationalizing stakeholder engagement in CSR: A process approach. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raufflet, E. Responsabilidad social corporativa y desarrollo sostenible: Una perspectiva histórica y conceptual. Cuad. De Adm. 2010, 43, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Server-Izquierdo, R.; Lajara-Camilleri, N. La gestión sostenible de las cooperativas. Los valores y principios cooperativos como referencia. AECA 2016, 115, 60–61. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Valdés, R.; Campillo-Alhama, C. Desarrollo local y relaciones públicas para grupos desfavorecidos en la Comunidad de Madrid. Prism. Soc. 2013, 10, 394–432. [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Fumás, V. Responsabilidad social corporativa (RSC) y creación de valor compartido. La RSC según Michael Porter y Mark Kramer. Rev. De Responsab. Soc. De La Empresa 2011, 3, 15–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, M.; do Céu Alves, M.; Oliveira, C.; Vale, V.; Vale, J.; Silva, R. Dissemination of social accounting information: A bibliometric review. Economies 2021, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Franco, M. The formulation and implementation of corporate sustainability strategy in organizations. In Management in Public Administration Information and Technology Education; Severo de Almeida, F.A., Malheiro da Silva, A., Tristão, G., Conti de Freitas, C., Eds.; University of Porto-FLUP: Porto, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, M.; Franco, M. The Corporate Sustainability Strategy in Organisations: A Systematic Review and Future Directions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochales-González, G. Modelo Explicativo de la Responsabilidad Social Corporativa Estratégica. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Economics and Business, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Sánchez, A.; Vaca-Acosta, R.M. Responsabilidad social corporativa y cooperativismo: Vínculos y potencialidades. CIRIEC 2005, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar]

- REScoop.eu is the European Federation of Citizen Energy Cooperatives. Available online: https://www.rescoop.eu/ (accessed on 26 May 2021).

- Pérez, I.C.; Celador, Á.C.; Zubiaga, J.T. Las cooperativas de energía renovable como instrumento para la transición energética en España. Energy Policy 2018, 123, 215–229. [Google Scholar]

- Falcón Pérez, C.E. Las cooperativas energéticas como alternativa al sector eléctrico español: Una oportunidad de cambio. Actual. Jurid. Ambient. 2020, 104, 50–108. [Google Scholar]

- Zadek, S. Titans or Titanic: Towards a Public Fiduciary. Bus. Prof. Ethics J. 2012, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, J.; Hurst, B. Public relations, futures planning and political talk for addressing wicked problems. Public Relat. Rev. 2019, 45, 101828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Etang, J.; McKie, D.; Snow, N.; Xifra, J. The Routledge Handbook of Critical Public Relations; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ingenhoff, D.; Marschlich, S. Corporate diplomacy and political CSR: Similarities, differences and theoretical implications. Public Relat. Rev. 2019, 45, 348–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdora, E.; Ferguson, M.A.; Duman, S.A. Corporate social responsibility and CSR fit as predictors of corporate reputation: A global perspective. Public Relat. Rev. 2016, 42, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunig, J.E.; Hunt, T. Managing Public Relations; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Eding, E.; Scholtens, B. Corporate social responsibility and shareholder proposals. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, E.; Melé-Carné, D. Corporate Social Responsibility Theories: Mapping the Territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melé-Carné, D. Corporate social responsibility theories. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility; Crane, A., Matten, D., McWilliams, A., Moon, J., Siegel, D.S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. The new story of business: Towards a more responsible capitalism. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2017, 122, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García-de-Leaniz, P.; Rodríguez-del-Bosque-Rodríguez, I. Revisión teórica del concepto y estrategias de medición de la responsabilidad social corporativa. Prism. Soc. 2013, 11, 321–350. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, A.; Moyano-Fuentes, J.; Jiménez-Delgado, J.J. Estado actual de la investigación en Responsabilidad Social Corporativa a nivel organizativo: Consensos y desafíos futuros. CIRIEC 2015, 85, 143–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, W. CSR 2.0 and the New DNA of Business. J. Bus. Syst. Gov. Ethics 2010, 5, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Servera-Francés, D.; Fuentes-Blasco, M.; Piqueras-Tomás, L. The Importance of Sustainable Practices in Value Creation and Consumers’ Commitment with Companies’ Commercial Format. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quazi, A.M.; O’Brien, D. An Empirical Test of a Cross-national Model of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 25, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandberg, L. La implementación de la RSC en la cadena de valor. Cuad. De La Cátedra “La Caixa” 2010, 6, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zadek, S. El camino hacia la responsabilidad corporativa. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2005, 83, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zadek, S. The Civil Corporation: The New Economy of Corporate Citizenship; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- CSR Strategy of Spanish Companies. Available online: http://www.mitramiss.gob.es/es/rse/eerse/index.htm (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Visser, W.; Courtice, P. Sustainability Leadership: Linking Theory and Practice. SSRN 2011, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portal de la Responsabilidad Social. Available online: http://www.mitramiss.gob.es/es/rse/index.htm (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- International Integrated Reporting Council. The International <IR> Framework; International Integrated Reporting Council: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). Available online: www.globalreporting.org/standards (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Brundtland, G.; Khalid, M.; Agnelli, S.; Al-Athel, S.; Chidzero, B.; Fadika, L. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; Development and International Co-operation: Environment; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development; United Nations Publication: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- The UN Global Compact. Available online: https://widgets.weforum.org/history/1999.html (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, Rio+20. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/rio20 (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- UN 2030 Agenda. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/ (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Grushina, S.V. Collaboration by design: Stakeholder engagement in GRI sustainability reporting guidelines. Organ. Environ. 2017, 30, 366–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Amor-Esteban, V.; Galindo-Álvarez, D. Communication Strategies for the 2030 Agenda Commitments: A Multivariate Approach. Sustainability 2020, 30, 366–385. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Hussain, T.; Zhang, G.; Nurunnabi, M.; Li, B. The Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals in “BRICS” Countries. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SDG Compass. La Guía Para la Acción Empresarial en los ODS; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Haro del Rosario, A.; Benítez-Sánchez, M.N.; Caba-Pérez, M.C. Responsabilidad social corporativa en el sector eléctrico. Finanzas Y Política Económica 2011, 3, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno de España. Spanish CSR Strategy; Ministerio de Empleo y Seguridad Social: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Law 54/1997, of November 27, on the Electricity Sector. Gobierno de España. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/1997/BOE-A-1997-25340-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- National Commission on Markets and Competition. Available online: https://www.cnmc.es/ (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- United Nations Division for Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/spanish/esa/desa/aboutus/dsd.html (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Duque-Orozco, Y.; Cardona-Acevedo, M.; Rendón-Acevedo, J.A. Responsabilidad social empresarial: Teorías, índices, estándares y certificaciones. Cuad. De Adm. 2013, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herremans, I.M.; Nazari, J.A.; Mahmoudian, F. Stakeholder relationships, engagement, and sustainability reporting. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, M.; Gaspar-González, A.I.; Sánchez-Teba, E.M. Sustainable social responsibility through stakeholders engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2425–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopazo-Fraguío, P. Informes de responsabilidad social corporativa (RSC): Fuentes de información y documentación. Rev. Gen. De Inf. Y Doc. 2012, 22, 279–305. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco-Toro, J.A.; Ferré-Pavia, C. La comunicación estratégica de la responsabilidad social. Razón Y Palabra 2013, 83, 342–357. [Google Scholar]

- Arenas-Torres, F.; Bustamante-Ubilla, M.; Campos-Troncoso, R. The Incidence of Social Responsibility in the Adoption of Business Practices. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunig, J. Publics, audiences and marjet segments: Segmentation principles for campaigns. In Information Campaigns: Balancing Social Values and Social Change; Salmon, C.T., Ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Grunig, J. A situational theory of publics: Conceptual history, recent challenges and new research. In Public Relations Research: An International Perspective; Moss, D., MacManus, T., Vercic, D., Eds.; International Thomson Business Press: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- IESE. PWC. Código de Gobierno Para la Empresa Sostenible; IESE: Barcelona, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Esman, M.J. The Elements of Institution Building. In Institution Building and Development; Eaton, J.W., Ed.; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Stocker, F.; de Arruda, M.P.; de Mascena, K.M.C.; Boaventura, J.M.G. Stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting: A classification model. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2071–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhang, T.; Yan, S. How Corporate Social Responsibility Influences Business Model Innovation: The Mediating Role of Organizational Legitimacy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillamon-Saorin, E.; Kapelko, M.; Stefanou, S.E. Corporate Social Responsibility and Operational Inefficiency: A Dynamic Approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunenberg, K.; Gosselt, J.; De Jong, M. Framing CSR fit: How corporate social responsibility activities are covered by news media. Public Relat. Rev. 2016, 42, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvasničková Stanislavská, L.; Pilař, L.; Margarisová, K.; Kvasnička, R. Corporate Social Responsibility and Social Media: Comparison between Developing and Developed Countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SGD Compass. Available online: https://sdgcompass.org/ (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM). Available online: http://www.efqm.es/ (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Morsing, M.; Schultz, M. Corporate social responsibility communication: Stakeholder information, response and involvement strategies. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2006, 15, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).