How Spatial Distance and Message Strategy in Cause-Related Marketing Ads Influence Consumers’ Ad Believability and Attitudes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Corporate Social Responsibility and Types of Cause-Related Marketing

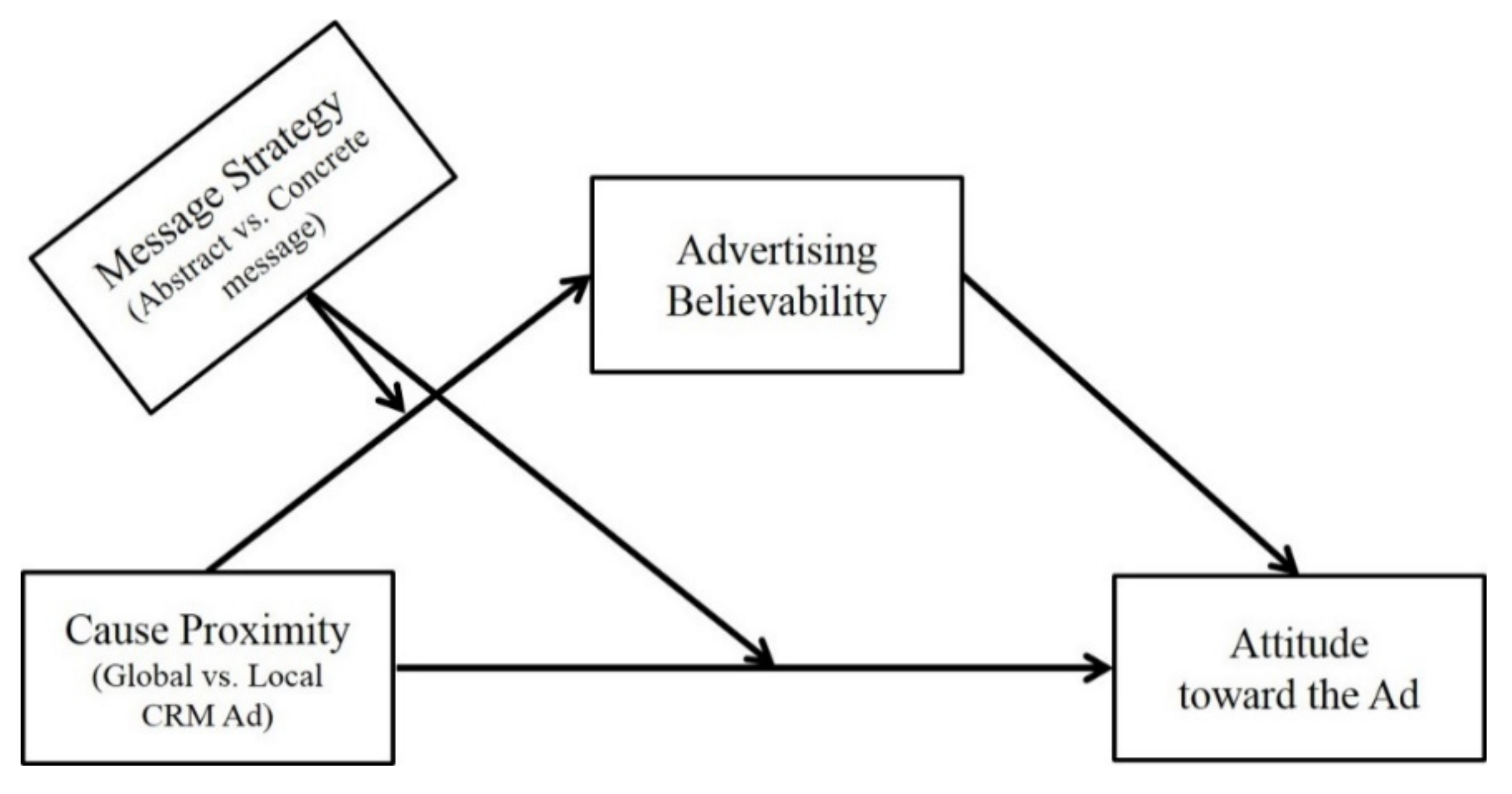

2.2. Construal Level Theory in the Context of CRM Advertising

2.3. The Mediating Role of Advertising Believability on Advertising Attitude

3. Method

3.1. Experimental Design

3.2. Sample and Procedure

3.3. Stimuli and Manipulation of Independent Variables

3.4. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Manipulation Checks

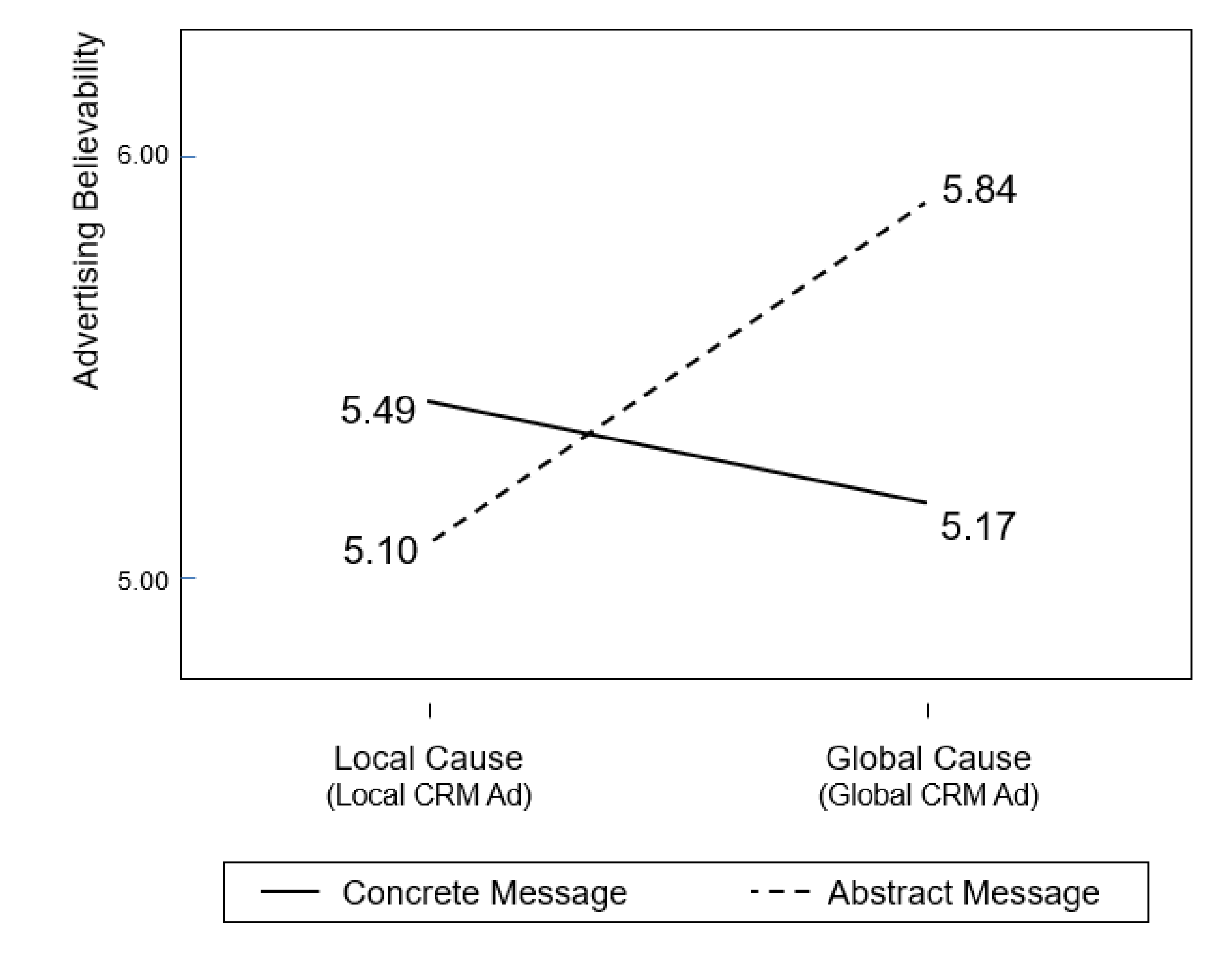

4.2. Interaction and Moderated Mediation Effects

5. Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Implications for Managers

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ross, J.K., III; Stutts, M.A.; Patterson, L. Tactical considerations for the effective use of cause-related marketing. J. Appl. Bus. Res. JABR. 2011, 7, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Varadarajan, P.R.; Menon, A. Cause-Related Marketing: A Co-alignment of Marketing Strategy and Corporate Philanthropy. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grau, S.L.; Folse, J.A.G. Cause-related marketing CRM: The influence of donation proximity and message-framing cues on the less-involved consumer. J. Advert. 2007, 36, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, S.; Kaufmann, H.R.; Ahmad, I.; Qureshi, I.M. Cause related marketing campaigns and consumer purchase intentions: The mediating role of brand awareness and corporate image. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 1229–1235. [Google Scholar]

- Haunschild, R.; Leydesdorff, L.; Bornmann, L.; Hellsten, I.; Marx, W. Does the public discuss other topics on climate change than researchers? A comparison of networks based on author keywords and hashtags. J. Informetr. 2019, 13, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Webb, D.J.; Mohr, L.A.; Harris, K.E. A re-examination of socially responsible consumption and its measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, D.W.; Lavack, A.M. Cause-Related Marketing: Impact of Size of Corporate Donation and Size of Cause-Related Promotion on Consumer Perceptions and Participation. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Anne-Lavack/publication/309076419_Cause-related_marketing_impact_of_size_of_corporate_donation_and_size_of_cause-related_promotion_on_consumer_perceptions_and_participation/links/58f53ac9458515ff23b56bee/Cause-related-marketing-impact-of-size-of-corporate-donation-and-size-of-cause-related-promotion-on-consumer-perceptions-and-participation.pdf (accessed on 1 January 1995).

- Sung, K.K.; Tao, C.W.W.; Slevitch, L. Restaurant chain’s corporate social responsibility messages on social networking sites: The role of social distance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyllegard, K.H.; Yan, R.N.; Ogle, J.P.; Attmann, J. The influence of gender, social cause, charitable support, and message appeal on Gen Y’s responses to cause-related marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 2010, 27, 100–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Crisafulli, B. How intensity of cause-related marketing guilt appeals influences consumers: The roles of company motive and consumer identification with the brand. J. Advert. Res. 2020, 60, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J. The role of construal level in message effects research: A review and future directions. Commun. Theory. 2019, 29, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, P.; Kline, S.; Dai, Y. Corporate social responsibility practices, corporate identity and purchase intention: Viability of a dual-process model. J. Public Relat. Res. 2005, 17, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.M.; Kim, H.; Woo, J. How CSR leads to corporate brand equity: Mediating mechanisms of corporate brand credibility and reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerro, M.; Raimondo, M.; Stanco, M.; Nazzaro, C.; Marotta, G. Cause Related Marketing among Millennial Consumers: The Role of Trust and Loyalty in the Food Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seitanidi, M.M.; Ryan, A. A critical review of forms of corporate community involvement: From philanthropy to partnerships. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2007, 12, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, S.; Brettel, M. Understanding the influence of corporate social responsibility on corporate identity, image, and firm performance. Manag. Decis. 2010, 48, 1469–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, J.B.; Sundgren, A.; Schneeweis, T. Corporate social responsibility and firm financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1988, 31, 854–872. [Google Scholar]

- Herremans, I.M.; Akathaporn, P.; McInnes, M. An investigation of corporate social responsibility reputation and economic performance. Account. Organ. Soc. 1993, 18, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility CSR: The role of CSR communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Temporal construal. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Förster, J. The effect of psychological distance on perceptual level of construal. Cogn. Sci. 2009, 33, 1330–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amit, E.; Algom, D.; Trope, Y. Distance-dependent processing of pictures and words. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2009, 138, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. The psychology of transcending the here and now. Science 2008, 322, 1201–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N.; Wakslak, C. Construal levels and psychological distance: Effects on representation, prediction, evaluation, and behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. Off. J. Soc. Consum. Psychol. 2007, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cesario, J.; Grant, H.; Higgins, E.T. Regulatory fit and persuasion: Transfer from “feeling right”. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jia, L.; Hirt, E.R.; Karpen, S.C. Lessons from a faraway land: The effect of spatial distance on creative cognition. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 1127–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakis, I.G.; Painesis, G. The impact of psychological distance and construal level on consumers’ responses to taboos in advertising. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R.; Kim, E.Y. Seeing the forest or the trees: Implications of construal level theory for consumer choice. J. Consum. Psychol. 2007, 17, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strizhakova, Y.; Coulter, R.A. Spatial distance construal perspectives on cause-related marketing: The importance of nationalism in Russia. J. Int. Mark. 2019, 27, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massara, F.; Scarpi, D.; Porcheddu, D. Can your advertisement go abstract without affecting willingness to pay? Product-centered versus lifestyle content in luxury brand print advertisements. J. Advert. Res. 2020, 60, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltramini, R.F. Advertising perceived believability scale. Proc. Southwest. Mark. Assoc. 1982, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Beltramini, R.F.; Evans, K.R.; Stan, S. Believability and comprehension of nutrition information in advertising. In American Marketing Association. Conference Proceedings; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000; Volume 11, p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- O’Cass, A. Political advertising believability and information source value during elections. J. Advert. 2002, 31, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomering, A.; Dolnicar, S. Assessing the prerequisite of successful CSR implementation: Are consumers aware of CSR initiatives? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, E.M.; Rifon, N.J.; Lee, E.M.; Reece, B.B. Consumer receptivity to green ads: A test of green claim types and the role of individual consumer characteristics for green ad response. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, J.L.; Beltramini, R.F. Exploring the perceived believability of DTC advertising in the US. J. Mark. Commun. 2007, 13, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A. Global Trust in Advertising and Brand Messages, Nielsen Global Survey; ACNielsen: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- O’Cass, A.; Griffin, D. Antecedents and consequences of social issue advertising believability. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2006, 15, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, A.Y.; Keller, P.A.; Sternthal, B. Value from regulatory construal fit: The persuasive impact of fit between consumer goals and message concreteness. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 36, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuhara, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Okada, M.; Kato, M.; Kiuchi, T. Designing persuasive health materials using processing fluency: A literature review. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scholl, S.G.; Greifeneder, R.; Bless, H. When fluency signals truth: Prior successful reliance on fluency moderates the impact of fluency on truth judgments. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2014, 27, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, Y.; Oh, S.; Yoon, S.; Shin, H.H. Closing the green gap: The impact of environmental commitment and advertising believability. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2016, 44, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.G.; Manika, D.; Stout, P. Causes and consequences of trust in direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2016, 35, 216–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, F.Y.; Chan, H.F.; Tang, F. The effect of perceived advertising effort on brand perception: Implication for retailers in Hong Kong. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2017, 27, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raziq, M.M.; Ahmed, Q.M.; Ahmad, M.; Yusaf, S.; Sajjad, A.; Waheed, S. Advertising skepticism, need for cognition and consumers’ attitudes. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2018, 36, 678–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semin, G.R.; Fiedler, K. The linguistic category model, its bases, applications and range. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 2, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Lutz, R.J.; Belch, G.E. The role of attitude toward the ad as a mediator of advertising effectiveness: A test of competing explanations. J. Mark. Res. 1986, 23, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Zhang, L.; Xie, G.X. Message framing in green advertising: The effect of construal level and consumer environmental concern. Int. J. Advert. 2015, 34, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Sengupta, J.; Hong, J. Why does psychological distance influence construal level? The role of processing mode. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 598–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.A.; Gnoth, J.; Strong, C. Temporal construal in advertising. J. Advert. 2009, 38, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangari, A.H.; Folse, J.A.G.; Burton, S.; Kees, J. The moderating influence of consumers’ temporal orientation on the framing of societal needs and corporate responses in cause-related marketing campaigns. J. Advert. 2010, 39, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodstein, J.; Butterfield, K.D.; Pfarrer, M.D.; Wicks, A.C. Guest editors’ introduction. Individual and organizational reintegration after ethical or legal transgressions: Challenges and opportunities. Bus. Ethics Q. 2014, 24, 315–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Koschate-Fischer, N.; Stefan, I.V.; Hoyer, W.D. Willingness to pay for cause-related marketing: The impact of donation amount and moderating effects. J. Mark. Res. 2012, 49, 910–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendini, M.; Peter, P.C.; Gibbert, M. The dual-process model of similarity in cause-related marketing: How taxonomic versus thematic partnerships reduce skepticism and increase purchase willingness. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 91, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.A.; Yuan, H. Effect of Ad-Irrelevant Distance Cues on Persuasiveness of Message Framing. J. Advert. 2015, 44, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source | MS | df | F | Partial eta2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cause Proximity | 3.14 | 1 | 4.36 * | 0.05 |

| Message Strategy | 2.94 | 1 | 4.09 * | 0.05 |

| Cause Proximity × Message Strategy | 4.76 | 1 | 6.61 * | 0.07 |

| Mean (SE, n) | ||||

| Concrete Message | Abstract Message | |||

| Local CRM Ad (Local Cause) | 5.68 (0.181, n = 22) | 5.58 (0.185, n = 22) | ||

| Global CRM Ad (Global Cause) | 5.60 (0.180, n = 23) | 6.42 (0.175, n = 24) | ||

| Source | MS | df | F | Partial eta2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cause Proximity | 0.92 | 1 | 0.84 | 0.01 |

| Message Strategy | 0.42 | 1 | 0.38 | 0.00 |

| Cause Proximity × Message Strategy | 6.33 | 1 | 5.75 * | 0.06 |

| Mean (SE, n) | ||||

| Concrete Message | Abstract Message | |||

| Local CRM Ad (Local Cause) | 5.49 (0.224, n = 22) | Local CRM Ad (Local Cause) | ||

| Global CRM Ad (Global Cause) | 5.17 (0.222, n = 23) | Global CRM Ad (Global Cause) | ||

| Attitude toward the Ad | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | t | |||

| Advertising Believability | 0.44 | 5.96 ** | ||

| Message Strategy (A) | 0.08 | 0.36 | ||

| Cause Proximity (B) | 0.06 | 0.30 | ||

| A × B | 0.45 | 1.45 | ||

| Covariates | ||||

| Age | 0.00 | 0.39 | ||

| Education Attainment | −0.14 | −0.91 | ||

| R2 = 0.623, F (1, 90) = 19.63 | ||||

| Conditional Mediation by Message Strategy | Bootstrapping Estimates | |||

| Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Mediator: Advertising Believability | 0.327 | 0.162 | 0.053 | 0.695 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, T.; Kim, J. How Spatial Distance and Message Strategy in Cause-Related Marketing Ads Influence Consumers’ Ad Believability and Attitudes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126775

Kim T, Kim J. How Spatial Distance and Message Strategy in Cause-Related Marketing Ads Influence Consumers’ Ad Believability and Attitudes. Sustainability. 2021; 13(12):6775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126775

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Taemin, and Jeesun Kim. 2021. "How Spatial Distance and Message Strategy in Cause-Related Marketing Ads Influence Consumers’ Ad Believability and Attitudes" Sustainability 13, no. 12: 6775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126775

APA StyleKim, T., & Kim, J. (2021). How Spatial Distance and Message Strategy in Cause-Related Marketing Ads Influence Consumers’ Ad Believability and Attitudes. Sustainability, 13(12), 6775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126775