Abstract

The strategic planning of rural development is focused on both economic growth and sustainable development. Sustainable rural development is essential for conserving and improving resources, while economic growth contributes to a better standard of living. The aim of the research is to determine, using the participatory rural appraisal (PRA) methodology on the example of the village of Zlakusa, the economic activities developed in the village, the importance of rural tourism, and the scope of sustainable development taken into account in rural development. The results of the research show that the success of the rural community depends on: diversification of economic activities, which is accompanied by cohesion of the population through association and organization; organized activities aimed at local or republican authorities; activation of human and social capital; and initiating activities involving marginalized groups. Educating the population outside formal education improves the sustainable and economic development of the village and enables rural tourism to become an important part of economic activities and a channel for the commercialization of natural and cultural contents.

1. Introduction

Tourism is considered to be a driver of economic development at local, regional, and national level. Given its linkages with other production sectors, it impacts a wide section of the economy.

In earlier research involving tourism impacts, focus was mainly put on mass tourism in resorts and major cities. It was believed that tourism does not have enough potential to boost development in rural areas, which was supported by the stance that rural areas are not sufficiently attractive for tourism. However, with an increase in the number of tourists in many tourist countries’ rural areas, it was soon realized that a carefully designed tourist product can serve as an instrument through which the economic situation in rural areas can be improved [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

The imperative of achieving economic, social, and environmental sustainability in local communities is certainly conducive to tourism. Tourism activities in rural areas are directly linked to sustainable development—by supporting the protection of natural and cultural capital of these areas and using them in a sustainable manner, they establish a balance between the economic and ecological dimensions of development. For this reason, rural tourism is considered to be one of the sustainable development channels through which rural areas can achieve economic, environmental, and sociocultural growth [11,12,13,14,15,16], as well as the basis for formulating strategies in rural development initiatives owing to its focus on local culture and the creativity, environment, and gastronomy of the rural community [17].

According to Eurostat’s urban-rural classification, rural areas in Serbia occupy about 80% of the territory of the Republic of Serbia, with about 63% of the total population living in these rural areas [18]. The process of transition and economic crisis in the 1990s had a significant impact on the entire country but a particularly negative impact on rural areas (resulting in even lower participation of rural areas in the overall GDP of the country). Developing tertiary activities in order to diversify economic activity and create additional income for rural households presents one way of retaining and bringing back the population to rural areas [19]. Analyzing natural and anthropogenic resources, it can be concluded that Serbia possesses significant potential for rural tourism development [20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

The research goal is to determine, through the analysis of certain elements of sustainable development (economic, social and environmental), whether and in which segments a small rural environment (Zlakusa village, City of Užice, Serbia) can be sustainable, and how much the diversification of economic activities contributes to its sustainability. Additionally, the aim of the research is to determine to what extent the village itself can initiate changes, as opposed to when it needs the assistance of municipality (local self-government) or individual ministries.

2. The Sustainability of Rural Areas through the Diversification of Economic Activities

It is often emphasized that rural tourism represents one of the approaches for balancing regional development in developing countries [27,28,29]. On the other hand, in developed societies, rural tourism is seen as a source of income for the local community and one of directions for the diversification of economic activities in rural areas [30]. However, in their strategies, both groups of countries point out that rural tourism must be based on the concept of sustainable development and good governance policy [31,32,33].

Of course, the role of local governance is also vital for the overall development of rural areas, as local institutions including civil society are well positioned to promote and create an enabling environment for community members to become innovative, creative, and productive [34,35,36]. Various studies emphasize their importance as they provide necessary planning and management frameworks for rural development, thus improving the socioeconomic conditions and well-being of poor people in rural communities [34,37,38,39,40].

However, increasing people’s participation in development activities is very important for achieving effective and sustainable development. Contemporary strategies for rural development have become based upon notions of self-help and bottom-up community-based initiatives. The role of local authorities is to generate motivation and encourage mobilization and participation of the local population in the decision-making process at the local level. Through self-help and self-reliance initiatives, the skills and resources of local community are mobilized in local planning development activities, reducing the economic burden on local governments and thus resolving, or at least alleviating, their key problem—lack of funds.

The agricultural and rural development strategy of the Republic of Serbia in the Priority Area 11 foresees a greater development of rural tourism. Namely, the diversification of economic activities and income transforms the rural economy by moving away from the activities of the primary sector of agriculture, industry, and tertiary activities. The improvement of the quality of life of the rural population will be encouraged by support for the regulation and renovation of the rural environment and the preservation of cultural heritage and natural wealth through projects of protection, conservation, and promotion of local architecture, landscapes, and other cultural, historical, and natural values [41].

According to the above plans, the main holder of certain activities is the local self-government—the municipality. The city of Užice has been actively involved in the implementation of strategic decisions in the past few years through the support or organization of trainings and workshops for rural areas. In cooperation with the Regional Chamber of Commerce of Užice, workshops were held on the topics “Support to women entrepreneurship” and “Development of start-up companies in the service sector in the organic production sector”, a revision of the local waste management plan of the city of Užice was carried out, information was provided by companies and entrepreneurs on state aid to SMEs and current support programs, and e-commerce workshops were held. Within the project “Regional value chain in the field of inter-municipal cooperation”, representatives of the tourism and catering sector discussed the possibilities for establishing a supply chain for local products for the tourism industry. Additionally, the project “Support to entrepreneurial activities of young people” within the framework of the Cross-Border Cooperation Program of the Republic of Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina has provided free workshops and trainings. The local self-government of the City of Užice is active in the development of the rural environment, and on the basis of the financial resources it has at its disposal, efforts are made to improve the quality of life and work in the countryside, thus contributing to the strengthening of social structures and social capital in rural areas.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodology and Research Design

The evolution of participatory approaches gives a new perspective on resolving problems in underdeveloped rural areas. Participatory rural appraisal (PRA) is considered to be one of the most popular and effective approaches for gathering information in rural areas. This approach was developed in the 1980s and early 1990s with a considerable shift in paradigm from a top-down to bottom-up approach and from blueprint to the learning process. PRA is based on village experiences where communities effectively manage their natural resources. As such, PRA and its methods make up an important part of participatory development strategies, which many donors and development agencies, whether government or NGOs, are now increasingly embracing, at least in terms of rhetoric [42,43].

PRA is a methodology of learning about rural life and environment from the rural people. Chambers [43] has defined PRA as an approach and method for learning about rural life and conditions from, with, and by rural people. He further stated that PRA extends into analysis, planning, and action. PRA closely involves villagers and local officials in the process [44].

The use of PRA can be found in the vast literature regarding many areas of natural resource management, such as participatory natural resource management [45,46,47,48], participatory watershed management, soil and water conservation [49,50], biodiversity, conservation, and protected area management [51,52,53,54,55].

Although the PLA/PRA methodology was originally intended for use in the fields of agriculture, the environment, and natural resources, in time, its application spread to other areas. We will mention several examples of more detailed publications: determining the level of poverty and violence in urban areas in Jamaica [56], rural planning in Indonesia [57], protection coral reefs on the island of Fiji [58], and sexual education and HIV prevention in adolescents in Zambia [59].

PRA is an internationally accepted qualitative survey technique that is widely used in different studies and international organizations such as the World Bank, Action Aid, ILO, Aga Khan Foundation, Ford Foundation, GTZ, SIDA, UNICEF, UNDP, and UNCHS (Habitat) [43]. However, some articles in the literature have already focused on the challenges facing PRA at particular levels [43,60]. One of the most comprehensive analyses involving PRA is provided by Leurs [42], using existent literature in PRA as well as data from a series of workshops held by the author with the staff of six NGOs that are promoting PRA in South Asia [42]. He groups these, in his opinion, major challenges into six different levels, namely the individual, community, organizational, project and programme, donor, and policy levels, and recognizes four key challenges which cut across all the above-mentioned levels at which PRA operates. These are inequalities in power, knowledge, time/money or its accessibility, and cultural differences [42].

Challenges facing PRA mainly concern training of PRA facilitators; the existence of cultural differences between PRA facilitators and community members; the power differential influencing the facilitator community relationship, where community members expect to gain rewards from the PRA process and do not see the process itself as a benefit; and the quality and quantity of participation in the development process.

Though PRA is currently lauded as the most appropriate participatory planning tool for rural development, the process has some drawbacks [61]:

- It may raise local expectations beyond what is feasible (affordable) if not well managed;

- Setting priorities may worsen internal conflicts in the community, especially when these are not clearly identified;

- Local politicians may not be comfortable with communities that exhibit high levels of independence, although PRA can be used to strengthen local authorities and local democracy as well;

- Outside facilitators may not buy into local needs and their priority.

An evolutionary leap in participatory methodologies resulted in the 1995 in the creation of a methodology of participatory learning and action-PLA. The PLA method allows the systematic situational analysis of the villages. At the same time, its application should bring closer to the rest of the rural population the idea of implementing their own commitment to the development of the village by mobilizing their own potentials. This method enables an impartial and transparent treatment of the problems and needs of the village, as well as an overview of natural resources and potentials of the village for the development of traditional activities whose reactivation is justified from the point of view of its sustainable development. Records of the past lifestyle, old crafts, and traditional methods of land use and cattle husbandry have been recorded, providing a basis for analyzing their possibilities in the light of world trends and open market conditions. The goal of the PLA method, however, is not a situational analysis itself but the initiation of a sustainable development process in the villages [62]. As far as Serbia is concerned, the PRA/PLA methodology has been used mostly in the area of rural development and in working with sensitive groups.

The application of the PRA/PLA methodology consists of two phases:

- Analysis of the situation in the community;

- Planning for the purpose of improving the situation in the community.

Applied tools for situational analysis (PRA/PLA tool) are the following:

- Presenting the situation in village;

- Timeline (historical mapping);

- Resource map;

- Seasonal calendar;

- Categorization according to the source of income;

- Categorization according to the standard of living;

- Creating job opportunities for improvement (planning tool).

PRA/PLA techniques used in this research include:

- Direct observation—observations are related to the questions: What? When? Where? Who? Why? How?

- Semistructured interviewing—a semistructured interviewing and listening technique uses some predetermined questions and topics but allows new topics to be pursued as the interview develops. The interviews are informal and conversational but carefully controlled;

- Seasonal calendars—variables such as soil preparation, sowing, plant protection, and harvesting periods can be drawn to show month-to-month variations and seasonal constraints and highlight opportunities for action;

- Mapping—making of maps which depict conditions and environment of the area. It increases the knowhow of the natives about their surroundings and the physical features of the area. It is used for the creation of a resource map;

- Permanent-group interviews—established small groups and farmers’ groups can be interviewed together. This technique can help identify collective problems or solutions.

After applying the PRA/PLA methodology, data summarizing was performed based on the three dimensions of sustainable development: economic, social, and environmental. Throughout the discussion, the strengths and weaknesses of each of the three dimensions of sustainability were pointed out.

Research questions in the work are related to the following:

- What are the potentials of the Zlakusa village, and what are the problems that rural people recognize?

- How have individual economic activities in the village developed over a longer period of time?

- What are the basic resources of the village and how are they deployed?

- How do some activities in the village take place depending on the time of the year and the season?

- How are the revenues generated and the household expenditures incurred in the village?

- What is the living standard of the households in the village?

- What can village residents do themselves to improve their lives and work in the countryside, and for what purpose do they need help from outside (from local government or ministries)?

- To what extent are the elements of sustainable development present in the village?

3.2. Data Collection and Sample

Data from this survey were collected in the village of Zlakusa, located in Western Serbia, in the Zlatibor district. Zlakusa is located in the valley of the Djetinja River, below Gradina (931 m above sea level). Once a village of poor potters, today it is a village of agricultural production, renovated crafts, and rural tourism. Trained facilitators conducted the process of data collection. The facilitators were representatives of the Rural Development Support Network, which was established within the project “Building the Rural Development Support System” by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Water Management of the Republic of Serbia. The training and work of the facilitators was supported by the Deputy Prime Minister’s Team for the implementation of the Poverty Reduction Strategy (March 2008–February 2009). According to the given criteria (rules) of applying the PRA methodology, the facilitators set topics for discussion, directed conversations, helped their groups with their knowledge and skills, and encouraged respondents’ creativity. In doing so, the facilitators did not in any way limit the work of the group or give directions to certain solutions during the discussion. Impartiality and careful listening are the basic characteristics of a good facilitator, which is achieved through training and documented through research.

PRA techniques were applied on a sample of villagers of different ages and genders. The number of participants in the plenum was 23 (7 women and 16 men) in “Presenting the situation in the village” and “Creating job opportunities for improvement (planning tool)”. In “History of the village”, four elderly villagers were interviewed. A “Resource map” and a “Seasonal calendar” were based on the statement of four younger locals (one woman and three men). In “Categorization according to source of income” and “Categorization according to standard of living”, statements were collected from five persons (two women and three men). The total sample included 36 locals (10 women and 26 men). The selection of participants in the survey was random, and participation was voluntary.

4. Results

4.1. Presenting the Situation in the Village

Presenting the situation in the village is applied as the first in a series of situational analysis tools (PRA) due to its possibility for gaining insight into the way locals see their situation, which problems and potentials they consider important, and providing a general framework for the application of other PRA tools (Table 1). The tools were used in plenum, which included 23 villagers (7 women and 16 men).

Table 1.

Potentials and Problems: the situation in the village Zlakusa (visualization).

According to the villagers, the main resource potentials of Zlakusa are the unpolluted environment and large areas of meadows and pastures as a potential for healthy food production, as well as rural tourism and pottery. Cattle and sheep farming are considered to be the most promising branches of agriculture. The production of beef, milk, and processed dairy products—cheese and “kajmak”—is dominant in cattle farming, while sheep farming is known for the production of lamb meat and less for the production of milk and cheese.

Fruit growing is reflected in the production of raspberries and plums. Plums are dried and sold or freshly used for the production of home-made brandy, while raspberries are sold in fresh condition unprocessed. Rural tourism represents a branch that has the potential to, although slowly, stimulate the growth of rural income and enable most of the agricultural products to be finally sold through the hospitality sector.

Rural tourism represents a great opportunity for a faster and more complex development of the village. To the attractiveness of the village and its surroundings contributes Potpećka Pećina Cave (about 550 m arranged for tourist visits), as well as traditional craftsmanship. Pottery is considered as representative of traditional crafting and unique culture of manufacturing vessels out of clay and calcite (potteries), which are made manually using a wheel. After production, the vessels are dried and baked on an open fire on wood, at a temperature of up to 800 °C [64]. The village is to a great extent equipped with infrastructure (electricity, water, sewerage). Land consolidation has been carried out, which has resulted in the agglomeration of agricultural plots and facilitated production. Petnica River has the potential for trout breeding, which is very successful in the area of Zlakusa–Potpeć. In addition to Petnica, watermills and cotton mills can be seen as a tourist rarity.

As disadvantages and problems that are slowing down the development of the village, locals pointed out the lack of veterinary clinics and the poor quality of the breeding stock. Due to outdated mechanization and livestock facilities, the efficiency of agricultural production and product quality has been reduced. The lack of cooperatives through which local people could sell their products and acquire cheaper reproducing materials makes agricultural production even more difficult. For vegetable crops, a big problem is the yellow snail appearing in the beginning of spring.

Although young people are staying in the village, Zlakusa has no kindergarten, gym, cultural center, ambulance, or post office, which can represent a limiting factor for the survival of local people. On the other hand, the vicinity of the main road, the gas pipeline, and the Belgrade–Bar line provide very good communication with the urban environment and ensure fast transport of goods, with the only obstacle in road transport being the absence of an adequate overpass that would allow the unimpeded traffic of larger vehicles (buses and trucks).

4.2. Village Timeline

This tool was applied in a group of four elderly villagers of Zlakusa. The timeline, as a PRA tool, provides insight into the village history and identifies events that are important for the agricultural development of the village and its critical points. Data obtained from a group of elderly villagers, who are authentic witnesses of all these events, include information that illuminate economic, sociocultural, and agricultural systems of the village through all changes that have occurred during that period, including the causes of the present situation. The timeline used in the paper covers a period of 60 years (Table 2).

Table 2.

History of the Zlakusa village.

The timeline shows that the best period for the development of agriculture was from 1970 to 1990, with a critical period from 1990 to the present. Rural tourism has been intensively developing since 2005.

4.3. The Resource Map of Village Zlakusa

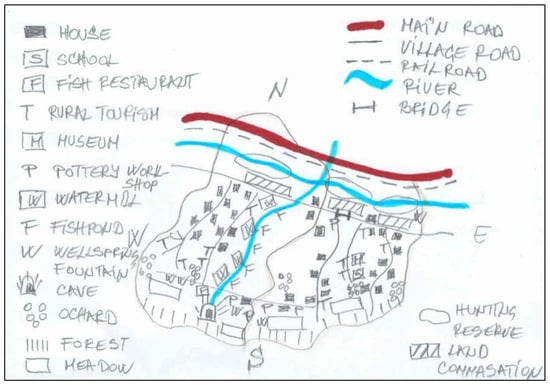

The use of the resource map helps us to gain insight into the way community members see their potentials, resources and possibilities for their exploitation, and the level of development of individual agricultural branches in the village. The tool is applied in a group consisting of three younger male participants and one young woman who made most of the observations about the environment. The resource map (PRA tool) has provided an insight into the natural resources of the village of Zlakusa that have the potential in fostering the development of certain agricultural branches and other nonagricultural activities (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The resource map.

The resource map shows that this is a village located in western Serbia, belonging to the type of upland villages. Nearby is the 1495-m high Zlatibor Mountain, which extends southwest of the mentioned village. The first larger town nearby is Užice, located 11 km to the west. The traffic connection with Užice is very good, since on the north side of village border passes the main road M-21, which branches out at Užice and connects Belgrade with Sarajevo and Podgorica. Along the main road passes the railroad Belgrade–Bar. The village is connected by an asphalted local road that branches out to the south, creating a dense network of uncategorized rural roads. Households are distributed on both sides of the road. The average number of household members is 3.3, while three generations often live together within a single household.

From the direction of Užice through the village flows the Djetinja River, parallel with the main road and the railway. Throughout the whole length of the river flow, bounded by a railway line, spreads a hunting reserve growing mostly pheasants, representing an exceptional potential for the development of hunting activities, especially hunting tourism. Another important river flow is the Petnica, whose source is found in Potpećka Pećina Cave in the far south of the Potpeć village. The Petnica flows into the Djetinja at the northern border of both villages, and it is famous for its large number of ponds and watermills extending on both sides and through the entire length of its watercourse. Especially interesting are fishponds, about 40 of them, thanks to which 16 households are engaged in the production of trout and make a living from it. It should be noted that there are two fish restaurants in the vicinity of the cave. As it is a limestone terrain, sources of pure drinking water appear in a few places, and they have been captured and converted into drinking fountains. The Petnica River and Potpećka Pećina Cave represent a unique tourist potential.

Along the southern border of the village stretches forest which, according to the locals, occupies a third of the village territory, while the meadows and pastures adjoin the forest and occupy the second third of the village area. The next stage relates to orchards located on the territory of the inhabited area, mostly in the vicinity of the Potpećka Pećina Cave. Consolidated land extends between the main village road and the Djetinja River, comprising fields and arable land. Orchards and consolidated land occupy the last third of the village territory.

A school with a small sports field is located in the center of Zlakusa village, but it is in a rather bad condition. Villages do not have a church or an infirmary. However, there is no lack of cultural and artistic content. Namely, there are a large number of households traditionally engaged in pottery. Potters from this region are not only well known throughout the country, but also the world; they have their own association and organize pottery-making colonies. An important addition is the existence of an open-air museum in Zlakusa called “Terzića Avlija”, which reflects the Serbian tradition and a way of life in the 19th century. An association totaling 12 households engaged in rural tourism rounds out the tourism potential and places it on the list of primary village activities along with pottery and fishing.

The resource map, as a PRA tool and indicator of the village’s development potential, provides a perspective concerning the possibilities for fruit production and small organic cattle farms, as well as the utilization of resources related to fishponds, apiaries, pheasants, medicinal herbs, etc. The resource map identifies potentials for organic production and the eco- and ethnotourism offers in the form of rural tourism.

4.4. Seasonal Calendar

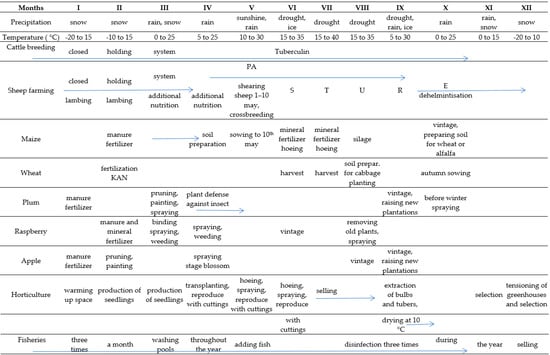

This tool provides information on the climatic conditions of the area, the most important branches of agriculture and nonagricultural activities in the local community (rural tourism, traditional crafts, small and medium enterprises, processing facilities, etc.), and the dynamics of the activity according to gender (emphasized in the study). All parameters have been visualized in a one-year period, for each month separately (Figure A1).

The use of the seasonal calendar does not imply obtaining precise information entered into the calendar by the PLA helpers—the implementation of this tool is left to the villagers themselves. The purpose of its application is not only gathering necessary information, but also involving locals in the process of representing their own living situation.

4.5. Economic Status of Domestic Households with All of the Above-Mentioned Activities

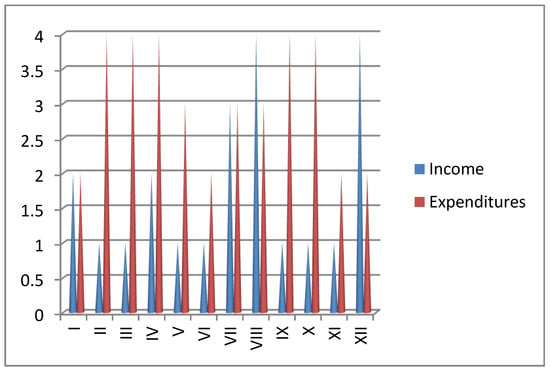

In the village of Zlakusa, income is generated throughout the year, but in the months of July and August, revenues are much higher due to raspberry sales. Additionally, in December, the largest part of the revenue comes from selling fish. In addition to the mentioned products, the villagers make earnings from rural tourism and selling milk, bulls, lambs, cabbage, and brandy (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Income and expenditures over the year (Source: The Authors and according to [63]).

According to local residents, expenses are present throughout the year, but they are highest in March and April when activities like land preparation, sowing, spraying, and crop cultivation are carried out, as well as in September and October when it is time for harvesting corn, picking fruit, and preparing land for individual cultures. Most of the money is allocated towards the purchase of fuel, spare parts, protective equipment, mineral fertilizers, concentrated nutrients, and labor.

4.6. Division of Labor by Gender and Dynamics of Activity

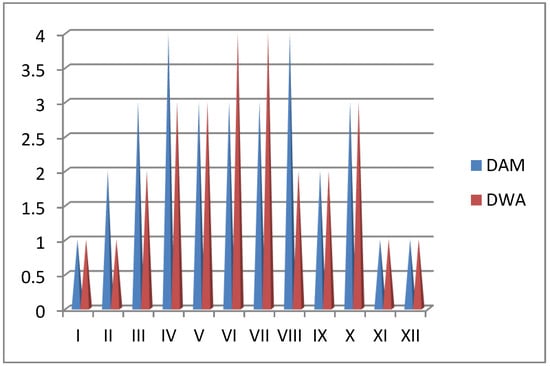

The activities of men and women cannot be determined precisely, since the work is performed jointly. Only fragment of activities during the summer (raspberry picking) and autumn (preparing winter stores) represent additional activities for the female population. The male population declared that they are generally the busiest in springtime, as well as in August during fruit picking. They also work more in October when land is prepared and winter crops are sown (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dynamics of activity of men and women during a year (DAM—Dynamics of men’s activity, DWA—Dynamics of women’s activities) (Source: The Authors and according to [63]).

4.7. Categorization According to Sources of Income

By categorizing the sources of income, we gain insight into the economic system and revenue structure of the members of the community. We become aware of the problems following the acquisition of income and can determine to what extent agricultural and nonagricultural sources of income are represented.

This categorization was applied in a group of five villagers (three men and two women) of Zlakusa. The categorization by source of income aims to show the share of agriculture in the total economic system of the village, i.e., to separate the revenues from agricultural and nonagricultural activities (Table 3).

Table 3.

Income in the village by the type of activity.

Regarding nonagricultural sources of income, the locals stated that around 200 villagers receive wages (20%) and that 25% of villagers receive pensions which are, in their opinion, significant sources of income. Participants of this categorization also mention earnings made by villagers who own trade and craft facilities (5%). In particular, they placed an emphasis on income from tourism and hospitality as new branches in the village—only 1% of the locals are engaged in these activities, but they still generate a significant income. Zlakusa village has become a recognizable tourist destination, which can be concluded from the resource map. This village also has potters (7%), as well as locals engaged in folk craftsmanship (10%) making woolen items and folk costumes and selling them both on domestic and foreign markets. Agricultural pensions go to 5% of the locals, but, as they are extremely low compared to the other earnings are not considered as significant revenue.

When talking about agricultural sources of income, the first place belongs to selling trout from private ponds within the households. According to the participants’ opinion, the number of such households is 16 or 5%, and they earn an annual income of about EUR 1 million. The second highest income comes from raspberries (80% of households) which are perceived as a profitable product. A total of 50% of households sell fattened cattle (one to five per year), and 10% of households sell calves and lambs (one to ten head per year). The locals do not perceive cattle husbandry as a significant income generator, since in the past decades, it was significantly larger in scale, as was milk production. Due to the extremely low prices and the unstable market, livestock farming has been slowly declining despite its potential in accommodation facilities, equipment mechanization, and knowledge. Rural tourism, which is constantly developing, and for which exists both human and natural potential, realizes 7% of household income. Rural tourism is followed by the sale of brandy, although in smaller quantities, from which 80% of households earn income. A total of 30% of households sell piglets but in quantities almost insignificant for the village as a whole, which is also the case for selling cheese and “kajmak” (25% of households). Cheese and “kajmak” are made in a traditional manner and had once played a significant role in household earnings. Villagers also mentioned the sale of milk and honey (in small quantities, 1% of households), and floriculture as a branch in its infancy (1% of engaged households). They stated that there were good conditions for this type of production, as well as the market for the sale of flowers.

4.8. Categorization According to Standard of Living

Categorization according to the standard of living gives us an insight into the socioeconomic standard of the local population. Members of the community participating in the research distinguish households according to standard of living. The goal is to classify all households by category, while listing the characteristics of different categories of living standards in a given community according to the visions of the participants.

The tool was applied in a group of five villagers (three men and two women) of Zlakusa village. This tool enables us to understand how residents differentiate depending on the household living standard, how many different standards they mention, and how many households are placed in each category. Participants in this categorization distinguished four categories of households comprising all households in the village (Table 4).

Table 4.

Categorization according to the standard of living.

There are 40% of households in the village categorized as above average. They are characterized by arable land of 2–5 ha, of which up to 0.3 ha is raspberries and 0.3–1 ha is plums. They have a tractor with all attachments and connecting machines (baler, cistern, picker). As for the stock fund, they own five to ten head of large cattle, five to ten sheep, and pigs for their needs (one or two sows and piglets). They have their own workforce, and in the season of field work and raspberry picking, they also hire seasonal workers. From nonagricultural sources of income, they have one or two members’ salaries, as well as a pension from one member’s employment. In this group, the local participants included 16 households with fishponds and 15 households with ownership of micro and small enterprises.

Average households have up to 2 hectares of arable land, about 0.1 ha of raspberries and 0.2–0.5 ha of plums. They own a cultivator with attachments, one to three large head of cattle, five to ten sheep, and pigs for their own needs. They have their own workforce. From non-agricultural income, wages are less, and pensions more often represented. Such households, in the opinion of the participants in the categorization, make 50% of total number of households in village.

Locals say that there are 5% of households below average. They have up to 0.2 ha of arable land, have no machinery, no large cattle, have one pig and chicken for their own needs. They have a pension either from employment or from agriculture.

The group of elderly and single households includes those with one or two older members over the age of 65. These households have about 0.1 ha of arable land, do not have machinery or livestock, and receive one of the pensions.

4.9. Creating Options for Improvement—Planning Tool

The tool was applied on a group of 23 locals (7 women and 16 men). Creating options as a planning tool is applied to the results of the first tool of situational analysis—“presenting the situation in the village”. After the application of other PRA tools and completion of the situational analysis, this tool, in the planning phase of the PLA method, returns to the problems identified by the locals using the PRA tool—presenting the situation in the village and categorizing the problems according to the ability to participate in their solution. Hence, the local participants in the group divided all of the identified problems into three groups: the problems that they can solve by themselves; those which, besides mobilizing their own resources, require assistance from outside; and those in the resolution of which they cannot participate (Table 5).

Table 5.

Creating options for improvement.

We without any assistance: The problems villagers pleaded to solve themselves are cooperation—the creation of cooperatives and associations of farmers—and organized purchase—realized through created associations. The result of the current individual performance is market noncompetitiveness.

We with the assistance from outside: These problems are primarily meant to be solved jointly, but according to the locals, although there is a good will on their part to partially participate, the other partner is hard to find. The problems of the village are as follows: old mechanization, old cattle husbandry facilities, absence of a veterinary clinic, lack of highly educated experts who would improve technology of agricultural production, and lack of warehouses where agricultural products would be stored to wait for a better price. Due to the high cost of irrigation systems, villagers are not currently able to buy them, which is why they expect the assistance of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Water Management (MAFWM). Until the establishment of the ministerial office in 2008, they did not even know that the Ministry of Agriculture subsidized such systems. An ambulance, kindergarten, and post office are institutions that are much needed and without which the village will not be able to function in the future. Problems regarding sewerage and gasification systems can also only be solved in this way.

Only with the help from outside: Road infrastructure and the railway overpass are problems which require urgent resolution. In addition, the villagers think that the state should protect producers and guarantee them a minimum purchase price that would cover production costs. A pest snail that appeared fifteen years ago threatens to suppress further vegetable production by which the village was recognizable. Poor breeding cattle is a consequence of poor seed selection and the absence of a selection service that would advise and control villagers regarding selection, improvement of racial composition, and controlling artificial insemination (they expressed suspicions concerning seed quality and its genetic potential).

5. Discussion

The overall vision for the sustainable development of the rural environment, as well as rural tourism, is the balance of economic, sociocultural, and ecological sustainability. Without the interaction and balance of these three components, it cannot be said that some area or activity is sustainable. Rural tourism based on sustainability principles offers elements of a rural environment and nature, but it also presents the traditional hospitality and living values of the local population.

On the example of the village of Zlakusa, with the help of the PRA method, every element of sustainability was examined using indicators that were evaluated and singled out according to importance by the locals themselves. Thus, the sustainability assessment is the result of self-analysis by the villagers, which is the best way to point out the existing problems of the village and understand the need to preserve existing resources and their rational use in the future (Table 6).

Table 6.

Sustainability elements of rural environment in Zlakusa village.

Sustainable rural development is a sensitive category for a small community, where many constraints on sources of financial investment and the application of knowledge are encountered. The rural areas are under the influence of negative demographic factors (low natural increase, departure of young people from the villages, high share of elderly population), as well as restrictions regarding economic development, which additionally makes rural development more difficult. In the literature, experts’ statements that villages in Serbia are dying can often be found [65,66,67].

The analysis of sustainable development in the village of Zlakusa monitored through all three elements of sustainability indicates that economic, sociocultural, and ecological sustainability is achieved and that many elements that can identify this village as an example of good practice are present.

Economic sustainability is represented by a few branches of agriculture (cattle husbandry, horticulture, crop farming, fishing, beekeeping, breeding pheasants), trade, micro and small enterprises, handcraft (pottery), and rural tourism. Diversified economic activity is very useful for a small environment, as many households are engaged in various activities to secure their income. Thus, pottery, from a craft that had almost completely disappeared, became a source of income for rural households with 30 active potters, mostly younger people, living in the village currently. Modern technologies, such as the possibility to sell via Internet, and strong promotional activity have contributed to the increase in sale of pottery in the country as well as around the world. The latest initiative launched in Zlakusa has the goal to make this village the center of pottery making in the Balkans [64]. For this purpose, the pottery fair “Lončarijada” is organized with potters gathering around from all over Serbia and abroad. The trademark of Association “Z” was promoted at Lončarijada in 2010, as proof of the traditional workmanship of products (clay + calcite), making products on a hand wheel, and baking the vessels over open fire. In this way, the brand of Zlakusa pottery has been developed, the production of souvenirs further improved, and the positive image of the village reinforced. However, potters did not recognize the need to unite and act on the Serbian market through a chain of retail stores (pottery from Bulgaria is being sold in stores, while crafts from Zlakusa cannot be bought). They sell their products in the village, along the main road, or by sending a product via mail to customers (communication channels are provided by phone, social networks, or e-mail).

Rural tourism, as a new economic branch in the village, is gaining momentum, since about 50 beds are categorized in households, and there is a camp within the “Terzića avlija” for the accommodation of tourists (using their own equipment or equipment rented in the camp). Within the offer, rural tourism combines the natural and cultural potentials of the village, thus gaining their commercial value, but also increases the added value of agricultural products distributed to guests through the sale of food and beverages. Rural tourism has the potential for significant development in the future, as attractive elements are diverse and their combination and complementarity can provide a very wide range of tourism products (a product intended for hikers, excursionists, nature lovers, pupils, etc.). Traditional food could also be a strong reason for the loyalty of tourists to rural areas [68]. A special element in attracting tourists is the kindness of the hosts, their preserved traditional way of life, and their hospitality towards the guests of the village.

Cattle farming, as a traditional agricultural activity in the mountain region, has been declining for a long time. In 2017, the local self-government, in order to improve the situation, took a number of measures in the form of subsidies to producers (for the purchase of Simmental cattle, sheep, and goats and for the procurement of the milking systems). All mentioned actions were undertaken on the basis of the program of support measures for the implementation of agricultural policy and rural development policy for the area of Užice [69]. This was one of the basic problems identified by rural people in research.

However, the economic sustainability of the village in the analysis of household categorization according to the living standard indicates that households that have a high standard are the ones where one or more members work in enterprises or have a pension from an older member of the household. This means that agriculture, crafts, and rural tourism are not sufficient for a household to have a higher living standard, and that precisely the income from salary is key for maintaining other household activities and often provides additional financial resources as an investment incentive.

The sociocultural sustainability of Zlakusa village is well developed and is present primarily through distinct human potential reflected in the fact that 50 highly educated individuals are living in the village, but also in a large number of young people who remain there. Social activity is manifested in the association of residents in different types of NGOs operating in the village on the preservation of tradition and customs, crafts, and culture and representing the negotiating power in front of the local self-government and ministries for various projects. An association of locals in this field and expert teamwork led to the fact that Zlakusa has been recognized as a village desirable for life, attractive for tourists, productive of Indigenous crafts (pottery-making, weaving traditional costumes), and good for investment. Thus, many cultural projects have emerged and survived, mostly related to the organization of events, promotion of tourism, establishment of a library and archives of the village, and more. In the period from 2001 to today numerous seminars, workshops, and trainings of locals have been organized where they have learned how to recognize and preserve their culture and tradition and how to place it on the market. The projects resulted from these seminars brought not only money to the village but a new and a wider way of thinking and understanding what the values of the village are and how to valorize them.

The sustainability of a local community and its culture and tradition is a complex activity that should not cause the loss of authenticity and succumb under the influence of commercialization. Namely, within the wider manifestation “Autumn in Zlakusa”, the demonstration of creating pots and roasting on an open fire is sidelined, while in the first years, it was presented as the most important part of the program. Although initially well conceived, the manifestation failed to meet demands of the wider community, so the hand wheel and the bonfire-“žižanica” [70,71] were replaced with loud music in the tents. In this example, it can be seen that uncontrolled exploitation of cultural resources can lead to phenomena that can even endanger the cultural good itself. Risks and damages can be avoided if the local community cooperates with institutions for the protection of cultural heritage and local tourist organizations [72]. The cultural value of the pottery of Zlakusa village is high, as evidenced by the fact that it is included in the list of elements of the intangible cultural heritage of the Republic of Serbia [73].

Environmental sustainability is represented through the care and rational use of natural resources. The village is making an effort to preserve unpolluted natural environment and natural habitats of certain flora, insects, birds, and mammals. The preserved natural environment is the result of the absence of industrial plants, as well as the managing of arable land in a rational manner through the low use of pesticides and herbicides (according to locals, wheat is not sprayed with chemicals). The care of water resources is reflected in the installation of biofilters on the Djetinja River (funds were provided by the Republic Directorate for Water 60%, the City of Užice and the Local Community of Zlakusa 40%), sealing off the spring water source, the installation of pipes, and the preservation of watercourses (rivers and streams) and their coastal belt. In previous years, the village fought against illegal dumps; an ecocamp was even launched in which volunteers from the country and abroad helped in the collection and proper disposal of bulky waste. Additionally, an ecological accident happened in 2010, when someone threw about half a ton of dead fish in the Djetinja River [74]. Against these occurrences, the local community is fighting together with inspections from the municipality (local level) and the police.

Rural households are always maximally oriented towards saving and utilizing all byproducts of plant or animal production. Herbal residue in the fields is chopped and ploughed, which contributes to fertilization, and the manure is used as an organic fertilizer in orchards and raspberry fields. The development of beekeeping and abundant pasturage are also indicators of preserved nature and a healthy environment. Developed infrastructure enables the sustainability of the local community as well as unobstructed economic activity in agriculture, micro and small enterprises, trade, and crafts. Local government, within its capabilities (annual budget projections), implements certain measures to improve life and work in the rural environment (asphalting the local road, reconstruction of the underpass, etc.). The amount of investments every year accounts from EUR 8000–12,500, since there are not enough financial resources for more expensive activities. Projects are planned according to initiatives from the Zlakusa local community (bottom-up), and the financing is most often participatory (33% is the participation of Zlakusa community, that is, the village’s inhabitants themselves, and 67% is the obligation of the City of Užice). The community of Zlakusa also provides part of the funds from donations from larger companies from the surrounding cities (e.g., Copper and Aluminum Mill, Sevojno) in order to realize more expensive projects. Similarly, subsidies in agriculture are 50% financed by the Ministry of Agriculture, and the rest is paid by farmers (e.g., for importing tractors). The local government recognized the value of Zlakusa as a tourist potential, and when it comes to tourism, Zlakusa gained the status of a location significant for the development of the City and now represents the eastern tourist point of the City [75]. The future project for tourism promotion envisions the construction of the cycling track Užice–Zlakusa.

For the needs of tourism, 60 km of pedestrian paths were marked, and over 550 m of the Potpećka Pećina Cave were also arranged for tours. In this way, the movement of tourists is directed towards marked paths and the use of certain resources under the condition of civilized behavior, and respect for the regime of space use is being controlled. Increasing the availability and attractiveness of the Potpećka Pećina Cave through infrastructure equipment and landscaping was carried out in 2012 with a project worth EUR 160,385. The project was implemented by the Tourism Organization of Užice (local level). The results were excellent: an increase in the number of tourist visits of 80% and an increase in the number of overnight stays in villages gravitating toward Potpećka Pećina Cave of 50% two years after completion of the project [76].

Traditional crafts cultivated in the village, such as pottery, weaving, and embroidery, are completely part of tradition and in accordance with ecological production. The goal of the village is that the implementation of some other ecological activities should lead to the proclamation of the village Zlakusa as the first ecological tourist village in the Zlatibor region.

The development of rural tourism in the future will have to take into account the number of tourists staying in the village and the consequences of increased pressure on the environment. For now, such pressure is not pronounced, since the number of tourists is not large (8000 tourists in 2009), but the concern about the resources must be continuous with the active participation of all inhabitants of the village.

The applied PRA methodology in the concrete example of the Zlakusa village proved to be a good way not only to determine the essential facts about the village but also to change the way people think and how they can learn to diversify their production. The interaction of the group of respondents with each other, as well as the interaction of the group with the facilitator, contributes to the powerful exchange of information and gained experience and gives confidence to the villagers to launch some new activities in the village. The respondents’ responses were positive because they had the opportunity to express their opinion and therefore increase their personal significance, at least in their own eyes (less in the community).

The limitation of the application of the method relates to the verification afterward of what has been determined by the study. It is not known to what extent the needs and activities in the village have been identified and realized. Additionally, there is no timeframe in which individual activities would be implemented. Finally, the development strategy of the village could be created as a result of this research, and that was not the case.

6. Conclusions

The rural areas of Serbia occupy about 80% of its total territory. About 63% of the population of Serbia lives and works in this territory, basing their work and survival mainly on natural resources: land, forests, water, ore, and others. Income in the countryside is lower than in urban areas, as is the case with employment opportunities. Therefore, one of the proposed solutions in the master plan for the development of rural tourism in Serbia is the development of rural tourism, which would contribute to the economic empowerment of the rural population and also to the strengthening of local and regional economies. The development of tourism positively affects almost all economic and noneconomic activities, that is, the development of the entire community.

On the example of the Zlakusa village, it is determined that the sustainable development of the village is possible, with the economic advancement and keeping the living standard of the population at an above average level. The main direction of actions that led to good results is certainly the diversified economic activity of the inhabitants of the village, followed by the cohesion of the population reflected in the association of the NGOs and organized activities towards local or republic authorities. The projects obtained in that way brought financial impulse which improved the activities and resources of the village. Significant impact on the organization of local inhabitants was made by the local government through training and workshops, as well as increased activities through a program of support measures for the implementation of agricultural policy and rural development policy. The local population recognized the resources that the village has at its disposal and understood how they can be valorized and what should be offered in rural tourism. Today, Zlakusa offers a complex tourist product, branded pottery, and souvenirs, with an improved image of the village and its surroundings.

In fact, we can say that this is a rural tourism based on the concept of sustainable development and good governance policy. Rural tourism has improved the social and economic status of the village and can be characterized as integral rural tourism (IRT), which is considered to be the best approach according to theory. This approach enables the highest level of satisfaction of the needs and demands of all interested groups in the rural area, achieving their own goals and protecting the environment [77], which has been determined by the analyses.

Human capital (knowledge and skills of the local population), as well as social capital (trust and networking), that exist among people in the community are very often underestimated. The challenge of diversifying the nonagricultural economy and managing changes lies in the construction and use of these forms of capital. Rural people often underestimate themselves and do not have the confidence to define the problem and organize in order to change something in their villages [66]. However, good results in Zlakusa were also achieved through the activation of certain marginalized groups, such as women (Women’s Association “Zlakušanke”). Additionally, young people had their chance to show their abilities through the activities of the “Youth for village” team, where they worked mostly on the promotion of villages, fairs, founding of the library, etc. Intellectuals living in the village also contribute to the development of individual activities and form an important part of the human potential that is an influential force in the village, but also in the surrounding cities (Village Development Council).

The sustainability of the rural environment is real, as the rural environment uses the knowledge on how to survive and how to maximize the use of products and byproducts of all forms of production from its past and tradition. What is now called “recycling” has been applied in rural areas since ancient times, as rationing and savings always followed the villages and their inhabitants.

The diversification of economic activities is largely represented as a necessary need for obtaining sufficient income for households and reaching a certain level of living standard, and not as a new measure of the Ministry in the rural development program. The diversification of economic activities is the way of survival of every rural environment and the struggle for survival in conditions of poor market development and low investment of capital and assets.

Sustainable rural tourism is a segment of the overall sustainability of the villages and the activity that brings new opportunities and sources of income for its residents. On the other hand, rural tourism is merited for the preservation of old crafts; for the commercialization of knowledge and skills by women, contributing in that way to the empowerment of women in the countryside; for the preservation of cultural values from oblivion by placing them on the market; and for the fact that preserved nature, rivers, and caves become elements of market attractiveness. Sustainability is therefore the essence of the concept of rural space and rural development, with rural tourism being only an upgrade to solid foundations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.Ć. and A.M.S.; Methodology, N.Ć.; Validation, N.Ć. and A.M.S.; Formal analysis, N.Ć., A.M.S., S.P., and B.J.; Investigation, N.Ć., A.M.S., and Ž.B.; Resources, N.Ć., A.M.S., J.B., Ž.B., S.P., and B.J.; Data curation, N.Ć. and A.M.S.; Writing—original draft preparation, N.Ć., A.M.S., and J.B.; Writing—review and editing, N.Ć., A.M.S., and J.B.; Visualization, N.Ć., A.M.S., J.B., Ž.B., S.P., and B.J.; Supervision, N.Ć.; Funding acquisition, N.Ć., A.M.S., J.B., Ž.B., S.P., and B.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development, Republic of Serbia (Grant No. 451-03-9/2021-14/ 200125; Grant No. 176017; Grant No. 176008).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the local community and the residents of Zlakusa village for their participation in the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Seasonal calendar.

References

- Dernoi, I. About Rural and Farm Tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 1991, 16, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaine, T.; Golan, M.; Var, T. Demand for Rural Tourism: An Exploratory Study. Ann. Tour. Res. 1993, 20, 770–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.; Brown, F. Tourism and Peripheral Areas; Channel View: Clevedon, UK, 2000; pp. 1–152. [Google Scholar]

- Ploeg, J.D.; Renting, H. Impact and Potential: A Comparative Review of European Rural Development Practice. Sociol. Ruralis 2000, 40, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrini, L. Rural tourism in Europe: Experiences and perspectives. In Proceedings of the 2002 Seminar held in Belgrade—Rural Tourism in Europe: Experiences, Development and Perspectives, Belgrade, Serbia, 24–25 June 2002; Available online: http://www.institutobrasilrural.org.br/download/20120219145557.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Viljoen, J.; Tlabela, K. Rural Tourism Development in South Africa: Trends and Challenges; Human Science Research Council Press (HSRCP): Cape Town, South Africa, 2007; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Q.J.; Lambe, W.; Freyer, A. Homegrown Responses to Economic Uncertainty in Rural America. Rural Realities 2009, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zorzoliu, R.; Iatagan, M. Rural tourism as an important source of income for rural places. Rev. Tur. 2009, 7, 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Muresan, I.C.; Oroian, C.F.; Harun, R.; Arion, F.X.; Porutiu, A.; Chiciudean, G.O.; Todea, A.; Lile, R. Local Residents’ Attitude toward Sustainable Rural Tourism Development. Sustainability 2016, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, B. Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: A case study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeder, R.J.; Brown, D.M. Recreation, tourism, and rural well-being. In Economic Research Report, No. 7; USDA; Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 1–33. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/46126/15112_err7_1_.pdf?v=0 (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Kim, H.I.; Chen, M.H.; Lang, S.C. Tourism expansion and economic development: The case of Taiwan. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghsetan, A.; Mahmoudi, B.; Maleki, R. Investigation of obstacles and strategies of rural tourism development using SWOT Matrix. J. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 4, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitasurya, V.R. Local Wisdom for Sustainable Development of Rural Tourism, Case on Kalibiru and Lopati Village, Province of Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 216, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coroș, M.M. Rural Tourism and Its Dimension: A Case of Transylvania, Romania. In New Trends and Opportunities for Central and Eastern European Tourism; Nistoreanu, P., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 246–272. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaides, A. Sustainable Ethical Tourism (SET) and Rural Community Involvement. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2020, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Obonya, G.; Fwayo, E. Integrating Tourism with Rural Development Strategies in Western Kenya. Am. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (SORS). Opštine i Regioni u Republici Srbiji [Municipalities and Regions in the Republic of Serbia]; Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (SORS): Belgrade, Serbia, 2014. (In Serbian)

- UN. Master Plan Održivog Razvoja Ruralnog Turizma u Srbiji [Master plan for the Sustainable Development of Rural Tourism in Serbia]; UN Joint Programme “Sustainable Tourism for Rural Development”: Belgrade, Serbia, 2011. (In Serbian)

- Živanović, J.; Marijana, P. Specifičnosti Sela u Srbiji u Kontekstu Turističkog Potencijala [The Specifics of the Village in Serbia in the Context of Tourism Potential]; The Institute of Architecture and Urban & Spatial Planning of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Todorović, M.; Bjeljac, Ž. Osnova Razvoj Ruralnog Turizma u Srbiji [The Basis of the Development of Rural Tourism in Serbia]. Bull. Serb. Geogr. Soc. 2007, 87, 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Stankov, U. Mogućnosti Kreiranja Održivog Ruralnog Turizma u Bačkoj [Possibilities of Creating Sustainable Rural Tourism in Bačka]. J. Geogr. Inst. Cvijic 2007, 57, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, Ž.; Manić, E. Cross-border cooperation, protected geographic areas and extensive agricultural production in Serbia. In The Role of Knowledge, Innovation and Human Capital in Multifunctional Agricultural and Territorial Rural Development; Tomić, D., Vasiljević, Z., Cvijanović, D., Eds.; European Association of Agricultural Economists: Belgrade, Serbia, 2009; pp. 397–405. [Google Scholar]

- Stojanović, Ž.; Manić, E. Održivost i diverzifikacija ruralne ekonomije—Analiza mogućnosti razvoja ekoturizma [Sustainability and diversification of the rural economy—Analysis of possibilities for development of ecotourism]. In Multifunkcionalna Poljoprivreda i Ruralni Razvoj (II)—Očuvanje Ruralnih Vrednosti [Multifunctional Agriculture and Rural Development (II)—Preservation of Rural Values]; Cvijanović, D., Hamović, V., Subić, J., Eds.; First Book; The Institute of Agricultural Economics: Belgrade, Serbia, 2007; pp. 333–341. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanović, V.; Manić, E. Evaluation of Sustainable Rural Tourism Development in Serbia. Sci. Ann. Danub. Delta Inst. 2012, 18, 285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Dašić, D.; Živković, D.; Vujić, T. Rural Tourism in Development Function of Rural Areas in Serbia. Econ. Agric. 2020, 67, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manić, E. Održivi ruralni turizam kao faktor razvoja ruralnih područja: Primer Srbije [Sustainable rural tourism as a factor for the development of rural areas: The example of Serbia]. Acta Geogr. Bosniae Herzeg. 2014, 1, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D.R. Tourism development and sustainability issues in Central & South Eastern Europe. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafunzwaini, A.E.; Hugo, L. Unlocking the rural tourism potential of the Limpopo province of South Africa: Some strategic guidelines. Dev. South. Afr. 2005, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.; Chabrel, M. Measuring Integrated Rural Tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2007, 9, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, L. A strategy for tourism and sustainable developments. World Leis. Recreat. 1990, 32, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpowicz, Z. The challenge of ecotourism: Application and prospects for implementation in the countries of Central & Eastern Europe and Russia. Tour. Rev. 1993, 3, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.R.; Kinnaird, V. Ecotourism in Eastern Europe. In Ecotourism: A Sustainable Option? Cater, E., Lowman, G., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Khongsatjaviwat, D.; Routray, J. Local government for rural development in Thailand. Int. J. Rural Manag. 2015, 11, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živojinović, I.; Ludvig, A.; Hogl, K. Social Innovation to Sustain Rural Communities: Overcoming Institutional Challenges in Serbia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlers, A.L.; Heberer, T.; Schubert, G. Whither local governance in contemporary China? Reconfiguration for more effective policy implementation. J. Chin. Gov. 2016, 1, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, D. Beyond Government: Organizations for Common Benefit; MacMillan: London, UK, 1991; pp. 1–216. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, D.J.A. The Restructuring of Local Government in Rural Regions: A Rural Development Perspective. J. Rural Stud. 2005, 21, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opare, S. Strengthening Community-based Organizations for the Challenges of Rural Development. Community Dev. J. 2007, 42, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Dou, X.; Li, J.; Cai, L.A. Analyzing government role in rural tourism development: An empirical investigation from China. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 79, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strategija Poljoprivrede i Ruralnog Razvoja Republike Srbije za Period 2014–2024 [Agricultural An Rural Development Strategy of the Republic of Serbia 2014-2024]; Ministry of Agriculture and Environmental Protection: Belgrade, Serbia, 2014; Available online: https://www.pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/SlGlasnikPortal/eli/rep/sgrs/vlada/strategija/2014/85/1 (accessed on 2 February 2021). (In Serbian)

- Leurs, R. Current challenges facing participatory rural appraisal. Public Adm. Dev. 1996, 16, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R. Rural Appraisal: Rapid, Relaxed and Participatory; IDS Discussion Paper 311. 1992. Available online: https://www.ids.ac.uk/download.php?file=files/Dp311.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- Cavestro, L. PRA—Participatory Rural Appraisal, Concepts, Methodologies and Techniques, Universita’ Degli Studi di Padova, Facolta’ di Agraria, Dipartimento Territorio e Sistemi Agro-Forestal: Padova. 2003. Available online: http://www.agraria.unipd.it/agraria/master/02-03/participatory%20rural%20appraisal.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2017).

- Probst, K.; Hagmann, J.; Fernandez, M.; Ashby, J.A. Understanding Participatory Research in the Context of Natural Resource Management—Paradigms, Approaches and Typologies. In ODI Agricultural and Extension Network Paper 130; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Borrini-Feyerland, G.; Pimbert, M.; Farvar, T.; Kothari, A.; Renard, Y. Sharing Power. Learning by Doing in Co-Management of Natural Resources throughout the World; IUCN CEESP CMWG: Tehran, Iran; IIED: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–456. [Google Scholar]

- Pimbert, M. Natural resources, people and participation. Particip. Learn. Action 2004, 50, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M. Assessing Natural Resource Management Challenges in Senegal Using Data from Participatory Rural Appraisals and Remote Sensing. World Dev. 2006, 34, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolavalli, S.; Kerr, J. Mainstreaming participatory watershed development. Econ. Political Wkly. 2002, 37, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaap, W.; Sakhar Nandi, S. Beyond PRA: Experiments in Facilitating Local Action in Water Management. Dev. Pract. 2005, 15, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimbert, M.; Pretty, J. Parks, people and professionals: Putting “participation” into protected area management. In Social Change and Conservation: Environmental Politics and Impacts of National Parks and Protected Areas; Ghimire, K.B., Pimbert, M.P., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 1997; pp. 297–330. [Google Scholar]

- Campbel, M.; Luckert, M.; Scoones, I. Local-Level Valuation of Savanna Resources: A Case Study from Zimbabwe. Econ. Bot. 1997, 51, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujja, B.; Pimbert, M.; Shah, M. Village voices challenging wetland management policies: PRA experiences from Pakistan and India. In Whose Voice? Holland, J., Blackburn, J., Eds.; ITDG Publishing: London, UK, 1998; pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, D.; Mayers, J.; Grieg-Gran, M.; Kothari, A.; Fabricius, C.; Hughes, R. Evaluating Eden: Exploring the Myths and Realities of Community-Based Wildlife Management: Series Overview; IIED: London, UK, 2000; pp. 1–124. [Google Scholar]

- Pan Luo, L.; Liu, L. Reflections on conducting evaluations for rural development interventions in China. Eval. Program Plann. 2014, 47, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, C.; Holland, J. Urban Poverty and Violence in Jamaica; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, N. The rush to scale: Lessons being learnt in Indonesia. In Who Changes? Institutionalizing Participation in Development; Blackburn, J., Holland, J., Eds.; IT Publications: London, UK, 1998; pp. 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, F.; Gormley, L. Coral Reef Conservation—Fiji; Project 162-8-176 Just World Partners (Formerly UKFSP), Annual Report 2000–2001, Darwin Initiative for the Survival of Species; Just World Partners: Penicuik, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Meera Kaul, S.; Zambezi, R.; Simasiku, M. Listening to Young Voices: Facilitating Participatory Appraisals on Reproductive health with Adolescents. CARE International and Focus on Young Adults: Zambia. 1999. Available online: http://www2.pathfinder.org/pf/pubs/focus/RPPS-Papers/pla1.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Mosse, D. Authority Gender and Knowledge: Theoretical Reflection on PRA. Econ. Political Wkly. 1994, 30, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turyatunga, F. Tools for Local-Level Rural Development Planning, Combining Use of Participatory Rural Appraisal and Geographic Information Systems in Uganda, WRI Discussion Brief; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vukadinović, A.; Milić, B.; Montelatici, G.; Paštrović, G. Priručnik za Metodologiju Participativnog Učenja i Delovanja (PLA/RRA) [A Handbook for Participatory Learning Methodology (PLA/RRA)]; Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management of the Republic of Serbia and the Network for Rural Development Support: Belgrade, Serbia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mreža za Podršku Ruralnom Razvoju [Rural Development Network]; Ministry of Agriculture, Trade, Forestry and Water Management of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2009; Available online: http://www.ruralinfoserbia.rs/karte_sela/kr/zlakusa-potpec.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2017).

- Pantić, N.; Drndarević, S. Grnčarija u Zlakusi—Od Starog Zanata Do Umetnosti, Zlakusa Nekad i Sad [Pottery in Zlakusa—From the Old Craft to Art, Zlakusa Then and Now]; Ethno park “Terzića avlija” and Etno Association “Homeland”: Zlakusa, Serbia, 2012. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Radovanović, S. Stanovništvo gradova i sela u Srbiji posle Drugog svetskog rata [Population of towns and villages in Serbia after the Second World War]. Bull. Ethnogr. Inst. SASA 1995, XLIV, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Živkov, G.; Dulić Marković, I.; Tar, D.; Božić, M.; Milić, B.; Paunović, M.; Bernardoni, P.; Marković, A.; Teofilović, N. Budućnost sela u Srbiji [The Future of the Village in Serbia]; Team for Social Inclusion and Poverty Reduction, Cabinet of the Deputy Prime Minister of European Integration: Belgrade, Serbia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Živković, J.; Lukić, T.; Ivkov-Džigurski, A.; Đekić, T. Policy responces to low fertility in Serbia. The case of municipality of Bela Palanka. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2017, 51, 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Vujko, A.; Petrović, M.D.; Dragosavac, M.; Ćurčić, N.; Gajić, T. The Linkage between Traditional Food and Loyalty of Tourists to the Rural Destinations. Teme 2017, 41, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Program Mera Podrške za Sprovođenje Poljoprivredne Politike i Politike Ruralnog Razvoja za Područje Grada Užice za 2017. Godinu [Program of Support Measures for Implementation of Agricultural Policy and Rural Development Policy for the Area of Užice for 2017]; Subvencije u Poljoprivredi [Subsidies in Agriculture]; City of Užice, Serbia. 2017. Available online: http://subvencije.rs/vesti/grad-uzice-7-podsticajnih-linija-za-poljoprivredu-u-2017-godini/ (accessed on 23 August 2017).

- Tomić, P. Grnčarstvo u Srbiji [Pottery in Serbia]; Ethnographic Museum: Belgrade, Serbia, 1983; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Đorđević, B. Tri Lica Tradicionalne Keramičke Produkcije u Srbiji [Three Facets of Traditional Pottery Making in Serbia]; Nacionalni Muzej: Beograd, Serbia, 2011; pp. 32–55. [Google Scholar]

- Krasojević, B.; Đorđević, B. Nematerijalno kulturno nasleđe: Turistički resurs Srbije [Nematerial cultural heritage: Tourist resource of Serbia]. In Proceedings of the Synthesis 2015—International Scientific Conference of IT and Business-Related Research, Belgrade, Serbia, 16–17 April 2015; pp. 561–565. [Google Scholar]

- Terzić, A.; Bjeljac, Ž.; Ćurčić, N. Common Histories, Constructed Identities: Intangible Cultural Heritage and the Rebranding of Serbia. Int. J. Intang. Herit. 2015, 10, 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- Janković, N. Djetinja Kao Deponija [Djetinja River as a Landfill]. Večernje Novosti (Newspaper). 18 August 2010, p. 8. Available online: https://www.novosti.rs/vesti/srbija.73.html:296716-Djetinja-kao-deponija (accessed on 1 November 2017).

- Public Enterprise “Direkcija za izgradnju”. Generalni Urbanistički Plan Grada Užica Do 2020 [General Urban Plan of the City of Užice until 2020]; City of Užice, Public Enterprise “Direkcija za izgradnju“: Užice, Serbia, 2011. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- City of Užice. Grad Užice, Strateški Plan Održivog Razvoja—Akcioni Plan 2012–2016 [City of Užice, Strategic Plan for Sustainable Development—Action Plan 2012–2016]. In Proceedings of the Ministry of Public Administration and Local Self-Goverment Republic of Serbia, Standing Conference of Towns and Municipalities, Užice, Serbia, 20 September 2011; p. 45. (In Serbian). [Google Scholar]

- Bryden, J.M.; Copus, A.; MacLeod, M. Rural Development Indicators; Report of the PAIS Project, Phase 1, Report for the Eurostat with LANDSIS; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2002.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).