Community-Based Tourism through Food: A Proposal of Sustainable Tourism Indicators for Isolated and Rural Destinations in Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Community and Gastronomy, the Perfect Match for Sustainable Development

3. Materials and Methods: A Proposal of Indicators to Assess Sustainable CBT

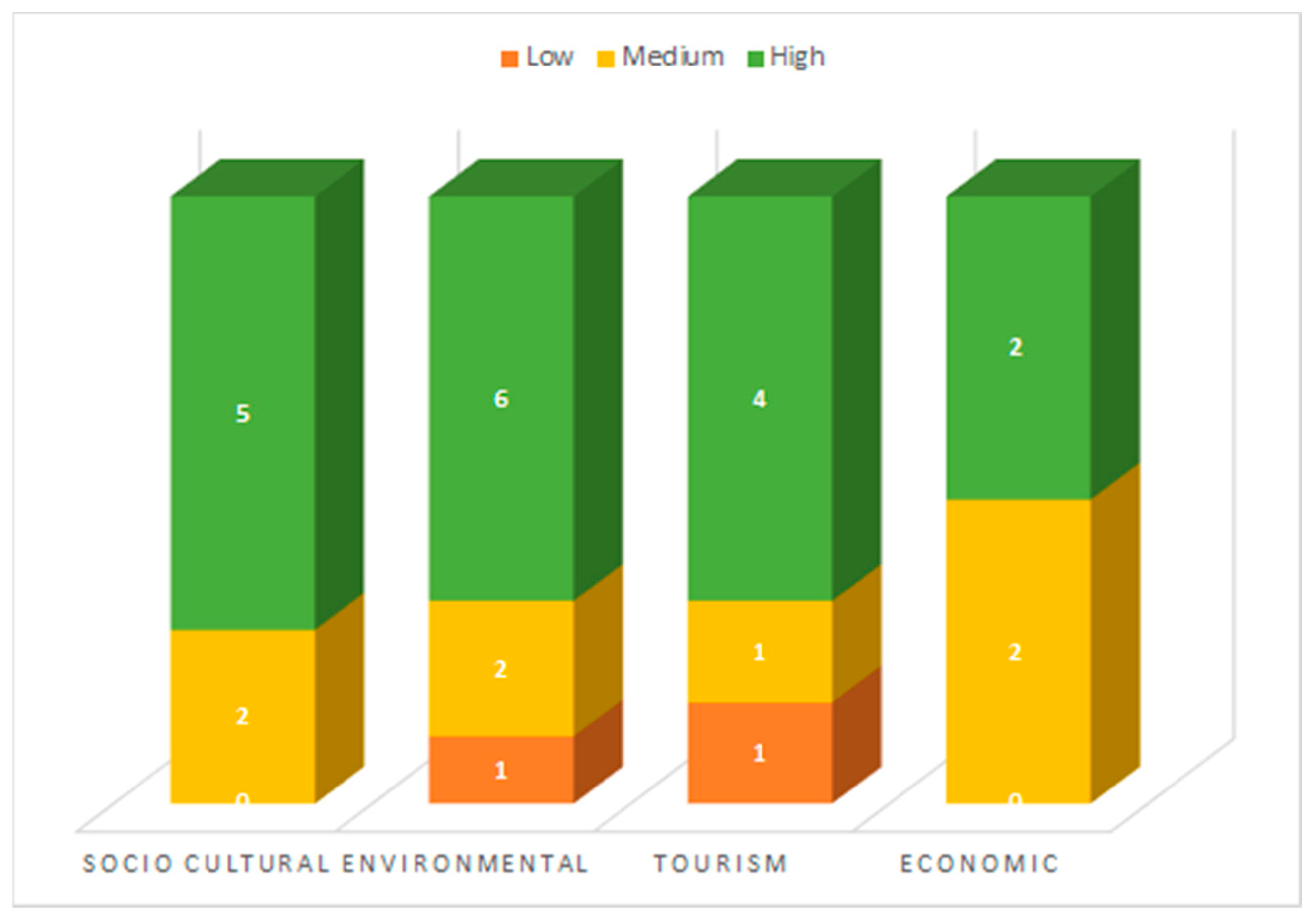

4. Results. Indicator Selection for Food Strategies in CBT

4.1. Socio-Cultural Indicators

4.2. Environmental Indicators

4.3. Tourism Indicators

4.4. Economic Indicators

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ruhanen, L. Local government: Facilitator or inhibitor of sustainable tourism development? J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koretskaya, O.; Feola, G. A framework for recognizing diversity beyond capitalism in agri-food systems. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 80, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghebaert, B. Working with vulnerable communities to assess and reduce disaster risk. Humanit. Exch. 2007, 38, 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J.; Ron, A.S. Heritage cuisines, regional identity and sustainable tourism. In Sustainable Culinary Systems: Local Foods, Innovation, and Tourism & Hospitality; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 275–290. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon, O.A.; González, H.E. El desarrollo económico local y las teorías de localización. Revisión teórica. Rev. Espac. 2018, 39, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals—Journey to 2030; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2017.

- Maslow, A.H. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Hall, C.M.; Esfandiar, K.; Seyfi, S. A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Understanding the Complexity of Economic, Ecological, and Social Systems. Ecosystems 2001, 4, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, J. La cultura: factor de desarrollo, prosperidad y felicidad. Fundacciones. Revista de Acción Cultural. 2009, 7, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Pigem, J. GPS (Global Personal Social). Valores Para un Mundo en Transformación; Editorial Kairós: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals: Goal 2 Zero Hunger. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/hunger/ (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- Higgins, V.; Dibden, J.; Cocklin, C. Building alternative agri-food networks: Certification, embeddedness and agri-environmental governance. J. Rural Stud. 2008, 24, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Morin, D.R. Indigenous communities and their food systems: A contribution to the current debate. J. Ethn. Foods 2020, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damman, S.; Eide, W.B.; Kuhnlein, H.V. Indigenous peoples’ nutrition transition in a right to food perspective. Food Policy 2008, 33, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Cerdà, M.; Rivera-Ferre, M.G. Indicadores internacionales de Soberanía Alimen-taria: Nuevas herramientas para una nueva agricultura. Revibec 2010, 14, 53–77. [Google Scholar]

- Echánove, F.; Steffen, C. Agribusiness and farmers in Mexico: The importance of contractual relations. Geogr. J. 2005, 171, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulet, S.; Mundet, L.; Roca, J. Between Tradition and Innovation: The Case of El Celler De Can Roca. J. Gastron. Tour. 2016, 2, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.M.M.; de la Fuente, G.M.C. Traditional Regional Cuisine as an Element of Local Identity and Development: A Case Study from San Pedro El Saucito, Sonora, Mexico. J. Southwest 2012, 54, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, K.; Slocum, S. Farm Diversification through Farm Shop Entrepreneurship in the UK. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2017, 48, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Stalder, F.; Hirsh, J. Open Source Intelligence. First Monday 2002, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondino, E. Strengthening the Link Between Conservation and Sustainable Development: Can Ecotourism Be a Catalyst? The Case of Monviso Transboundary Biosphere Reserve, Italy. Master’s Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gascón, J.; Cañada, E. Viajar a Todo Tren: Turismo, Desarrollo y Sostenibilidad; Icaria: Barcelona, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater, B. How disability studies and ecofeminist approaches shape research: Exploring small-scale farmer perceptions of banana cultivation in the Lake Victoria region, Uganda. Disabil. Glob. South 2017, 2, 752–776. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, E. Culinary tourism-a hot and fresh idea. TourismReview. com. 5–6 December 2008. Available online: https://www.tourism-review.com/travel-tourism-magazine-culinary-tourism-a-hot-and-fresh-idea-article677 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Boniface, P. Tasting Tourism: Travelling for Food and Drink; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidel, A. New Challenges in Rural Development a Multi-Scale Inquiry Into Emerging Issues, Posed by the Global Land Rush. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sidali, K.L.; Kastenholz, E.; Bianchi, R. Food tourism, niche markets and products in rural tourism: Combining the intimacy model and the experience economy as a rural development strategy. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 23, 1179–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Cultural Heritage and Tourism: An Introduction; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2011; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Aulet, S.; Mundet, L.; Vidal, D. Monasteries and tourism: Interpreting sacred landscape through gastronomy. Rev. Bras. Pesqui. Turismo 2017, 11, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Halldórsdóttir, Þ.Ó.; Nicholas, K.A. Local food in Iceland: Identifying behavioral barriers to increased production and consumption. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 115004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forson, P.W.; Counihan, C. (Eds.) Taking Food Public: Redefining Foodways in a Changing World; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. El Gobierno de los Bienes Comunes: La Evolución de las Instituciones de Acción Colectiva; No. E14-295; UNAM-CRIM-FC: Cuernavaca, Mexico, 2009; ISBN 978-968-16-6343-8. [Google Scholar]

- Durston, J. ¿ Que es el Capital Social Comunitario? Cepal: Santiago, Chile, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M.; Cohen, A.P. The Symbolic Construction of Community. Man 1988, 23, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ballesteros, E. Social-ecological resilience and community-based tourism: An approach from Agua Blanca, Ecuador. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverack, G.; Thangphet, S. Building community capacity for locally managed ecotourism in Northern Thailand. Community Dev. J. 2007, 44, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. The primacy of climate change for sustainable international tourism. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 21, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Human Development Report 2011. Sustainability and Equipty. A Better Future for All. 2011. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/271/hdr_2011_en_complete.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Sparks, B.A.; Bowen, J.T.; Klag, S. Restaurants and the tourist market. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2003, 15, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, E.; Lamb, D. Extraordinary or ordinary? Food tourism motivations of Japanese domestic noodle tourists. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 29, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, M. Between protection and progress: An actor oriented approach to cultural tour-ism development in Kenya. Ph.D. Thesis, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, D.W.; Cottrell, S.P. Evaluating tourism-linked empowerment in Cuzco, Peru. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 56, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, J.D. Camponeses e Impérios Alimentares; Lutas por Autonomia e Sustentabilidade na era da Globalicação; UFRGS Editora: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- RITA, Red Indígena de Turismo de México. 2010. Available online: http://www.rita.com.mx/ (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Patel, L.; Kaseke, E.; Midgley, J. Indigenous welfare and community-based social development: Lessons from African innovations. J. Community Pract. 2012, 20, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiste, M.; Youngblood, J. Protecting Indigenous Knowledge and Heritage: A Global Challenge; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- SECTUR: Gastronomía Mexicana. 2014. Available online: http://www.sectur.gob.mx/blog-de-lasecretaria/2014/09/05/gastronomia-mexicana/ (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- UNESCO (n.d.). Cultural Landscapes. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/culturallandscape/ (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- Treserras, J. El efecto turístico de los sellos UNESCO relacionados con la gastronomía en el espacio cultural Iberoamericano. In Gastronomia y Turismo; CIET: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2017; pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago-Mejía, B.E.; Martínez-Menez, M.R.; Rubio-Granados, E.; Vaquera-Huerta, H.; Sánchez-Escudero, J. Variabilidad espacial de propiedades físicas y químicas del suelo en un sistema la-ma-bordo en la Mixteca Alta de Oaxaca, México. Agric. Soc. Desarro 2018, 15, 275–288. [Google Scholar]

- Palomino Villavicencio, B.; Gasca Zamora, J.; López Pardo, G. El turismo comunitario en la Sierra Norte de Oaxaca: Perspectiva desde las instituciones y la gobernanza en territorios indígenas. El Periplo Sustentable 2016, 6–37. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.C.; Sirakaya, E. Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1274–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H. Can community-based tourism contribute to sustainable development? Evidence from residents’ perceptions of the sustainability. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Ítems de referencia para publicar Protocolos de Revisiones Sistemáticas y Metaanálisis: Declaración PRISMA-P 2015. Rev. Española Nutr. Hum. Dietética 2015, 20, 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- Blancas, F.; Lozano, M.G.; González, M.; Caballero, R. Sustainable tourism composite indicators: A dynamic evaluation to manage changes in sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1403–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M. Sanctions and tourism: Effects, complexities and research. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 22, 749–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukersmith, M.S.; Millington, M.; Salvador-Carulla, L. What is case management? A scoping and mapping review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2016, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Delgado, A.; Palomeque, F.L. Measuring sustainable tourism at the municipal level. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indicators of Sustainable Development for Tourism Destinations: A Guidebook; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2004; Available online: http://sdt.unwto.org/sites/all/files/docpdf/finalreport-bohol2008.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- SECTUR Sustainable tourism program in Mexico. 2013. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/sectur (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- European Commission. The European Tourism Indicator System. ETIS Toolkit for Sustainable Destination Management; European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hanai, F.Y. Sistema de indicadores de sustentabilidade: uma aplicação ao contexto de desenvolvimento do turismo na região de Bueno Brandão, Estado de Minas Gerais, Brasil. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo García, M.; Enríquez Rocha, P.; Meléndez Herrada, A. Gestión comunitaria y potencial del aviturismo en el Centro de Ecoturismo Sustentable El Madresal, Chiapas, México. El Periplo Sustentable 2017, 564–604. [Google Scholar]

- OECDiLibrary. Health at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015; Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-2015_health_glance-2015-en (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Asmelash, A.G.; Kumar, S. Assessing progress of tourism sustainability: Developing and validating sustainability indicators. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernat, L.; Gourdon, J. Paths to success: Benchmarking cross-country sustainable tourism. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1044–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.-G.; Kirsch, L.J.; King, W.R. Antecedents of Knowledge Transfer from Consultants to Clients in Enterprise System Implementations. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Andrades-Caldito, L.; Sánchez-Rivero, M. Is sustainable tourism an obstacle to the economic performance of the tourism industry? Evidence from an international empirical study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio González, R.; Serrano Barquín, R.D.C.; Palmas Castrejon, Y.D. Patrimonialización y patrimonio inmaterial como elemento dinamizador de la economía local en Zacazonapan, Estado de México. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2018, 4, 409–434. [Google Scholar]

- Bringas, O. Rutas alimentarias. Identificación de elementos básicos para su creación en la sierra alta de Sonora. Tesis de maestría en Promoción y Desarrollo Cultural. Doctoral Dissertation, Universidad Autónoma de Coahuila, Hermosillo, Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Salido Araiza, P.; Banuelos Flores, N.; Romero Escalante, D.M.; Romo Paz, E.L.; Ochoa Manrique, A.I.; Rodica Caracuda, A.; Cervantes, O. El patrimonio natural y cultural como base para estrategias de turismo sustentable en la Sonora rural. Estud. Soc. 2010, 17, 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- Twining-Ward, L.; Butler, R. Implementing STD on a Small Island: Development and Use of Sustainable Tourism Development Indicators in Samoa. J. Sustain. Tour. 2002, 10, 363–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Objectives | Indicator | Dimension | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional skills and abilities attributed to the level of schooling, training in community tourism, food production and traditional knowledge. | Socio-cultural | 1. Existence of plans to protect food heritage or food production. | 1. Determine how many plans exist at the destination for the protection of tangible and intangible heritage, especially related to food and traditional food production. |

| 2. Engagement of local communities in food-producing and involvement of different stakeholders in decision-making processes. | 2. Quantify the participation of groups in different actions and activities in their region. | ||

| 3. Traditional food knowledge (handcrafts, recipes, gastronomy culture, ancestral methods) (cultural heritage, tangible and intangible). | 3. Evaluate the population’s knowledge regarding their traditions, traditional dishes and community. | ||

| 4. Role of food traditions in social cohesion. | 4. Determine the role of food as an element of social cohesion (social events related to food, charity, etc.). | ||

| 5. Employment in the food and tourism sectors. | 5. Quantify the number of jobs related to food production and related to tourism. | ||

| 6. Average salary of women in the tourism and gastronomy industry. | 6. Determine the role of women in the industry and ascertain their salary. | ||

| 7. Recognition of women’s work within the community. | 7. Determine the level of Recognition of women’s work within the community. | ||

| Conservation actions ancient recipes with traditional vegetation. Diversification of food production. | Environmental | 8. Level of community involvement in tourism | 8. Identify the % of community involvement in tourism. |

| 9.Use of local products in food preparation. | 9.Determine origin of ingredients and food elements (how much of food production comes from local producers). | ||

| 10. Use of endogenous seeds. | 10. Identify how many endogenous seeds are used in gastronomy. | ||

| 11. Level of biodiversity in seeds and food-related elements. | 11. Identify how many different species and seeds there are in the local food traditions. | ||

| 12. Use of ancestral techniques in agriculture. | 12. Identify and list ancestral practices in agriculture. | ||

| 13. Use of ancestral techniques and methods in conservation and cooking of food. | 13. Identify and list ancestral conservations and cooking techniques. | ||

| 14. Use of renewable energies or techniques respectful of the environment. | 14. Identify best practices in agriculture with regard to sustainability. | ||

| 15. Percentage of the region under a protection plan (natural heritage). | 15. Ascertain percentage of region covered by a protection plan or declaration. | ||

| 16. Regenerative community tourism agenda. | 16. Identifying the destination has a regenerative community tourism agenda. | ||

| Loss of agricultural, forest, wetlands, infrastructure for lodging, food and equipment for tourists. | Tourism | 17. Infrastructure for hospitality managed by local communities. | 17. Determine percentage of hospitality infrastructures (hostels, rooms, etc.) run by locals. |

| 18. Suppliers of restaurants or food establishments run by local communities | 18. Determine percentage of food-related services run by locals. | ||

| 19. Number of local tour guides. | 19. Determine number of local tour guides compared with external tour guides. | ||

| 20. Number of travel agencies, tour operators or external agents involved in tourism activities. | 20. Determine number of intermediaries in tourism activities and conditions under which they operate (percentage of benefits for locals). | ||

| 21. Percentage of tourists and visitors regarding the local population | 21. Determine number of visitors per establishment. | ||

| 22. Average visitors per day, length of stay and level of seasonality in tourism | 22. Determine main visitor traits, especially regarding seasonality. | ||

| 23. Percentage of tourists that are satisfied with the visit and experience in the local community | 23. Determine tourists’ level of satisfaction regarding the experience they have with locals. | ||

| Economic resources of the organization. Employment and job opportunities for the community. | Economic | 24. Changes in land tenure. | 24. Identify changes in land tenure caused by tourism activities. |

| 25. Capital for reinvestment. | 25. Identify where income from tourism is spent and level of reinvestment in activities supporting the community. | ||

| 26. Contribution of tourism to the destination’s economy. | 26. Determine the importance of tourism as economic activity among all economic activities in the community. | ||

| 27. Daily spending per tourist in local communities (accommodation, food, handcrafts not in intermediaries or external companies). | 27. Determine the average expenditure per tourist in the community, without considering the money spent on intermediaries or other companies outside the community |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sosa, M.; Aulet, S.; Mundet, L. Community-Based Tourism through Food: A Proposal of Sustainable Tourism Indicators for Isolated and Rural Destinations in Mexico. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6693. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126693

Sosa M, Aulet S, Mundet L. Community-Based Tourism through Food: A Proposal of Sustainable Tourism Indicators for Isolated and Rural Destinations in Mexico. Sustainability. 2021; 13(12):6693. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126693

Chicago/Turabian StyleSosa, Mariana, Silvia Aulet, and Lluis Mundet. 2021. "Community-Based Tourism through Food: A Proposal of Sustainable Tourism Indicators for Isolated and Rural Destinations in Mexico" Sustainability 13, no. 12: 6693. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126693

APA StyleSosa, M., Aulet, S., & Mundet, L. (2021). Community-Based Tourism through Food: A Proposal of Sustainable Tourism Indicators for Isolated and Rural Destinations in Mexico. Sustainability, 13(12), 6693. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126693