“There is a difference between belief in a set of propositions and a faith which enables us to put our trust in them.”

“Capitalism has created incredible wealth, produced goods and services for millions of people around the world, and created jobs, but the pandemic is highlighting and exacerbating key market failures and government gaps.”

1. Introduction

The question of whether companies should maximise shareholder value or stakeholder welfare has been debated since the 1970s [

3], and has seen renewed interest recently in the wake of the current COVID-19 pandemic. As a result of COVID-19, businesses are now facing various challenges such as greater interdependencies, hidden vulnerabilities, and health and safety hazards for both employees and consumers. The pandemic has amplified existing societal inequalities and pushed them to the forefront of public consciousness [

4] (p. 1206), inevitably encouraging companies to reconsider their future corporate strategies and effectiveness and the endurance of their current business models. Companies are prioritising issues such as governance frameworks, corporate objectives, possibilities for developing more sustainable and localised supply chains, and possibilities for working remotely. The pandemic has revived the debate surrounding CSR and is fast constructing a new landscape for the sustainable development of businesses.

Companies and governments have been broadly involved in efforts to address social and environmental challenges and mitigate vulnerability in the business setting. CSR can contribute to the “

normalization, reinforcement, and reduction of economic inequalities in society” [

4] (p. 1206), and the pandemic has led to a sharp increase in attention to CSR considerations from both governments and market participants because of its exposure of major and broad vulnerabilities in the operational environments of companies [

5]. The needs of vulnerable parties have become an even more urgent priority, and are increasingly apparent as the world struggles against the pandemic.

Strategies to combat the crisis very much depend on building and accelerating resilience in the interplay between companies, organisations and societies, with a renewed emphasis on environmental, economic, and social strategy alongside more effective ways to offer managerial guidance for long-term value creation. In partnership with governments and citizens, corporations are legally required or encouraged to voluntarily fulfil their shared responsibilities to contain the spread of the virus and mitigate its economic and social risks and impact.

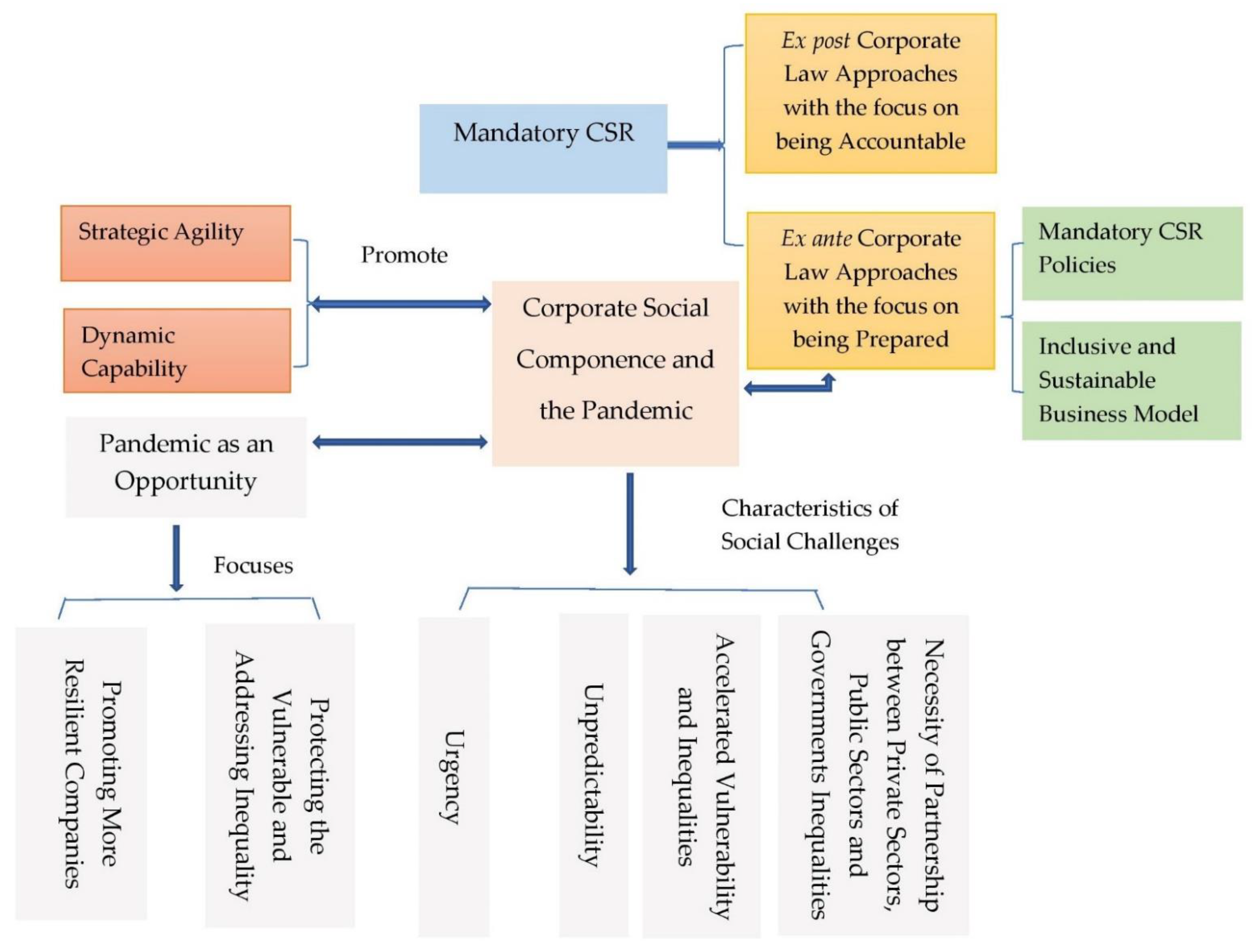

Despite its all-pervasive effects, the pandemic presents a unique opportunity for companies and policy makers to analyse in real time the effectiveness of current mandatory CSR approaches. Instead of focusing on accountability mechanisms, as in the traditional emphasis of CSR laws, regulatory approaches may be introduced to assist companies to make plans and policies to manage the risks associated with the pandemic and in order to manage the overall uncertainty. These approaches will enable corporations to revisit their corporate strategy and prepare revised business plans and CSR spending proposals, focusing on building long-term resilience and organisational strategic agility [

6,

7,

8] (p. 47). Long-term resilience will enable companies to address systemic inequalities, whereas strategic agility will support them to make strong strategic commitments and maintain their ability to manage and adjust to continuous changes in the era of the pandemic.

This article aims to investigate the rationale for and the focus of mandatory CSR in the era of the pandemic, using mandatory CSR policies and inclusive and sustainable corporate models as two examples of ex ante mandatory CSR measures. There are still plenty of incidents and tragedies where corporate imperatives are not neatly aligned with the long-term interests of society, and discussions to tackle these challenges typically take the form of “naming and shaming” reports [

9], legal action from stakeholders [

10], and administrative sanctions [

11]. This article aims to offer robust but respectful discussion about what can really be done to prevent these harms through corporate law.

The paper is designed to be a mid-stream retrospective look at diverting and balancing the legislative emphasis, considering what we have learned to date from the pandemic. In the long term, such progressive approaches will also promote strategic agility, increase investment, protect and attract customers, and enhance stakeholder loyalty, since responsible and ethical companies are likely to be remembered by stakeholders in years to come [

12].

Much of the pre-COVID-19 interdisciplinary research on CSR and corporate law has emphasised the importance of mandatory CSR and proposed a regulatory framework enforced by corporate law and governance mechanisms [

13,

14,

15]. However, scholars have made few attempts to differentiate between ex ante and ex post CSR law approaches. Moreover, the pandemic has clearly challenged a number of existing focuses, and ex ante mandatory CSR research, which is key for (re-)building more resilient companies and stakeholder networks in the mid- and post-pandemic periods, has mostly been ignored. This paper will fill this gap as an original attempt to correlate ex ante CSR regulatory approaches with the consequences of the social challenges brought by the pandemic. The article discusses the function of corporate law approaches in assisting companies to adapt to the “new normal” and support their recovery and renewal. It is hoped that these approaches will enhance CSR awareness and offer realistic routes for promoting CSR activities, addressing vulnerability, and building residence for companies through company law in response to amplified social inequalities.

In the private sector, the research will assist companies to understand the importance of being prepared for unpredictable social challenges. The research will also support companies to “

redesign their organizations to create more equal societies” [

4] (p. 1206), and radically reconsider and redefine their relations with stakeholders based on communication, cooperation, supervision, and care, in order to build “

appropriate (and often new) organizational capabilities, innovation, and entrepreneurship” [

16] (p. 279) and resilience for future crises. Ex ante legislative approaches are expected to help companies to produce innovative CSR policy to manage their stakeholder paradoxes and ultimately foster their competitiveness. For policy makers, the research will be helpful to lower the level of uncertainty in CSR law design and implementation, and to support legislators to take this crisis as a revelation and an opportunity for possible reforms. The research findings will support legislators and policy makers to understand the legislative options and the necessity of government interventions on business decisions, by providing examples of existing legislation to identify best practice and facilitate legal transplantation.

The article proceeds as follows. An introduction to the methodology is provided in

Section 2.

Section 3 will contextualise a few characteristics of social challenges that have arisen in light of the pandemic. Following the analysis of the social challenges,

Section 4 discusses the possibilities of using the pandemic as an opportunity to protect the vulnerable and address inequality, in order to build more resilient companies in the long term.

Section 5 critically analyses the rationale and effectiveness of mandatory CSR.

Section 6 discusses the advantages and nature of ex ante legislative approaches and introduces “corporate social competence” as a compliance principle.

Section 7 investigates two detailed ex ante legislative approaches to promote “corporate social competence”, including mandatory CSR policy and legally recognised sustainable business models. Finally, there are some concluding remarks.

2. Literature Review and Methodology

2.1. Literature Review

The relationship between CSR and corporate law has been discussed by various scholars, and the emphasis has traditionally been on how to promote more accountable companies, regarding corporate law involvement as an innovation in favour of multi-faceted corporate accountability [

17,

18,

19]. However, these augments have strong links with remedies and sanctions and ignore the preventive function of corporate law, as well as the importance of developing risk and crisis management programmes and policies [

20]. Despite this wide and multi-disciplinary recognition, there is no consensus about the motivation, definition, implementation, or function of mandatory CSR [

21]. Arguments in relation to the focus and application of mandatory CSR constantly change according to the economic climate, corporate scandals, and academic research agendas [

22].

The COVID-19 crisis is highlighting one of the most fundamental tensions that directors face, namely the tension between the complex and dynamic nature of stakeholders’ needs in the era of the pandemic and the limited resources and energy that corporations have available to attend to those needs competently and effectively. Companies with an embedded CSR strategy and high ethical standards are better prepared to perform these tasks, ultimately contributing to more resilient societies. Due to the recency of the pandemic, researchers in the field of business ethics, corporate management, corporate governance, and CSR have only just started to investigate the implications of the crisis, largely focusing on changes in the role of corporations in society more generally as governments come under pressure to take the pandemic as an opportunity to solve social and environmental problems [

23].

Some scholars have approached the issue of CSR and COVID-19 from different angles, and have called for the creation of plans and strategies for a sustainable recovery. Mahmud et al. explore corporations’ responses to the pandemic in order to support their vital stakeholders, including society as a whole, through CSR initiatives. Their research findings demonstrate respect for the employees and a focus on stewardship relations between companies, customers, and communities [

24]. However, only a small sample of responses have been investigated in the US; Kramer offers an overview of what companies can do to help various stakeholders in the era of the pandemic [

25], but he does not consider the need for collective action during the crisis, particularly in terms of government interference.

Bea et al. investigate the relationship between CSR and stock returns during the COVID-19 market crisis [

26]. However, their conclusions do not indicate a conclusive correlation between CSR performance and stock return which legal scholars could rely on to support law reform and legislative focuses. Crane and Matten aim to identify the key areas where CSR research has been challenged by the pandemic, such as stakeholders, societal risk, supply chain responsibility and the political economy of CSR, although they do not propose any specific approaches to tackle these issues [

27]. Manuel and Herron claim that the corporations have engaged in a wide range of philanthropic activities during the pandemic, but they have had disparate impacts and may in fact increase inequality, with a particularly negative impact on lower-income individuals [

28]. This study limited the scope of CSR by focusing on philanthropic responsibilities, and does not make proposals to deal with increased inequality. In contrast, Hassan et al. focus on one aspect of CSR, namely information discourse, and suggest approaches for how to enhance the quality of reporting to make it more stakeholder friendly [

29]. Nevertheless, this study only predicts the future of one aspect of mandatory CSR, namely the mandatory adoption of integrated reporting.

Other authors investigate related issues by focusing on specific industries, such as the hotel industry [

30], the tourism and hospitality industry in general [

31], the industrial sector of Sialkot [

32], and the hospitality industry [

33], or specific stakeholders such as employees [

34], consumers [

35], communities [

24,

36], and suppliers [

37]. In addition to the research findings on specific industries and stakeholders, this article aims to provide an argument in favour of promoting stakeholders’ interests in a collective manner through ex ante corporate law approaches that may be enacted in any jurisdiction in response to the challenges posed by the pandemic.

Generally speaking, the limited existing literature on CSR and the pandemic tends to treat the pandemic as a societal problem, and assumes that companies need to take steps to respond to the economic consequences and consider their contribution to ease the crisis. The pandemic directs researchers towards different ways of conceptualising CSR and corporate objectives. There has been no research approaching this significant topic through the lens of corporate law, which may be used to redefine the focus of CSR in the era of the pandemic. This gap, which is created by the unique nature of CSR challenges and the complexity of sustainability issues affecting a wide range of stakeholders, needs to be filled through legal approaches. It is hoped that this research approach will inspire and support governments and companies to achieve a more robust CSR awareness and practice, in order to generate realistic routes to mitigate vulnerability and build resilience for companies in response to amplified social inequalities.

2.2. Analytical Strategies

To determine the rationale for CSR law reform beyond mandatory CSR expenditure in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, this paper adopts a mixed methodology consisting of doctrinal, theoretical, interdisciplinary, and socio-legal research. Parts of this research adopt the doctrinal approach, with findings based on analysing and contextualising relevant legal authorities, primarily statutes, and case law. This approach involves theory-testing within the areas of CSR and strategic agility, and knowledge-building research on the compliance principle for corporate social competence. The research studies existing corporate laws such as the Indian Companies Act 2013 and the UK Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020, related legislation such as the case law in relation to the business judgement rule, and authoritative analytical materials on mandatory CSR. We also take an integrated theoretical approach, using management, business ethics, and economic theories to rationalise ex ante law-making endeavours to promote more resilient companies. Ex ante law theory is used as a theoretical framework and provides a coherent account of the preventive aspects of CSR law. It specifies the relations between corporate strategies and the legislative environment surrounding corporate decisions and corporate models. This also evidences the interdisciplinary nature of the research, as the theoretical framework is supported by management theories such strategic agility and dynamic capability.

While doctrinal analysis forms a central thread, the article also provides a critical socio-legal element that discusses the latest scholarly advances in the field of CSR law, and also addresses the pressing issue of the pandemic. The discussions of ex ante company law approaches and their function in tackling social challenges are inherently socio-legal; after all, the law is a social phenomenon, as pointed out by Cotterrell [

38] (p.296). Lady Hale, the former president of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, also highlighted the significance of this approach, particularly the fact that a number of socio-legal studies have been cited in court [

39].

This article provides a critical socio-legal study that brings together the latest scholarly advances on CSR and the pandemic, and at the same time addresses the pressing issue of the advantages and function of ex ante corporate law approaches to prepare businesses to overcome future crises like COVID-19 and become more resilient. This kind of socio-legal research will not only inform policy makers and legislators, but, more importantly, will further our understanding of the role of corporate law and corporations in modern society [

40]. The approach is functional and appropriate to interpret and clarify an ambiguous field such as CSR law in its social context of addressing urgent social challenges in the era of the pandemic, as well as the ethical implications of companies’ responses during the recovery stage to strike a balance between individual stakeholders’ interests and the sustainable development of companies.

2.3. Methodology Framework

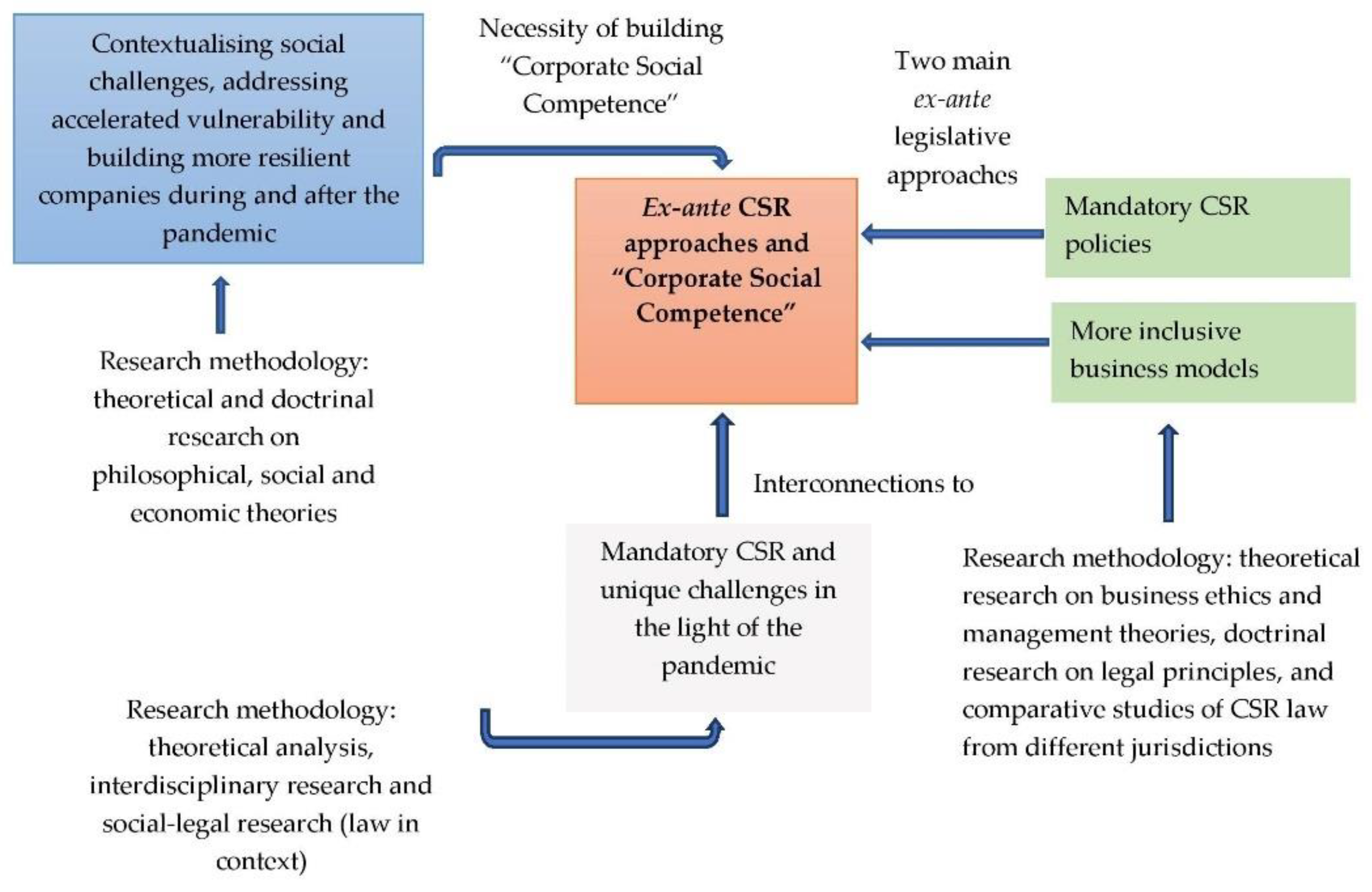

The methodology framework (

Figure 1) consists of theoretical, doctrinal, interdisciplinary, and social–legal research described in three parts of the article. First (presented in blue), the article contextualises the social challenges of the pandemic in

Section 3, and investigates the connection between accelerated vulnerability and more resilient companies in

Section 4. Second (presented in grey), the rationale and functions of mandatory CSR and corporate law approaches through doctrinal and theoretical research are examined in

Section 5. Third (presented in red and representing the main theme of the article), in

Section 6, the study examines relationships between ex ante CSR approaches and the challenges brought by the COVID-19 pandemic, in order to introduce the notion of “corporate social competence” in response to the current crisis and future crises. Fourth (presented in green), in

Section 7, the article contextualises two specific ex ante CSR approaches through comparative, theoretical, and doctrinal research.

3. Characteristics of Social Challenges in the Era of the Pandemic

A pandemic is defined as “an epidemic occurring worldwide, or over a very wide area, crossing international boundaries and usually affecting a large number of people” [

41]. We have contextualised the following characteristics commonly observed in the social challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, in order to shed light on the legislative approaches that are most suitable to tackle these challenges.

3.1. Urgency

Although country-led control measures to contain the spread of the coronavirus have been diverse, most actions have been branded as urgent with immediate effect, taken to address the most pressing challenges of the threat posed by the pandemic. For example, a “pandemic emergency unemployment compensation” programme was introduced in the US under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act 2020, aiming to provide an extension to regular unemployment insurance benefits. In the UK, the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020 made significant changes to UK insolvency law and introduced permanent measures such as restrictions on the termination of contracts for the supply of goods and services in Section 14 of the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020, together with urgent temporary measures in response to the pandemic such as the temporary suspicion of wrongful trading rules in Section 12 of the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020. Companies also came under pressure to raise urgent bank funding in response to COVID-19-related challenges.

3.2. Unpredictability

Although it is clear that the COVID-19 crisis has exposed a plethora of social problems with enormous economic and social consequences, an accurate assessment of the impact has been largely unattainable. Such an assessment depends on a wide range of issues such as the development and rollout of vaccines, government policies in response to pandemic-related challenges, and, of course, corporations’ attitudes, plans, and actions to deal with these challenges. Unpredictability also comes from the complicated social challenges and risks brought by COVID-19, which has magnified existing problems and shone an uncompromising light on existing tensions and paradoxes between stakeholders in the complex business setting. New uncertainties have arisen from many sources as a direct result of the pandemic, while existing uncertainties were exacerbated and accelerated as a result of various responses to the virus.

3.3. Accelerated Vulnerability and Inequalities

The COVID-19 crisis has revived debates around stakeholder vulnerability, and is fast constructing a new landscape for the scope of vulnerable parties in society. The pandemic has also laid bare many global inequalities in company operations and their global supply chains, such as modern slavery and employees with poor working conditions. The Clean Clothes Campaign reported that the pandemic “

has had direct and catastrophic consequences” for many vulnerable employees in textile supply chains, with many workers left without pay, employment, or social protection [

42]. As a result, the pandemic represents a unique opportunity to redefine CSR’s conceptual boundaries and routes of implementation, due to the vast spectrum of unprecedented government interference and the urgency of addressing vulnerability in stakeholder communities.

3.4. Necessity of Partnership between Private Sectors, Public Sectors, and Governments

In an era of such uncertainty, companies are able to use their industrial experience and expertise to provide creative solutions by pooling their knowledge and wisdom together in response to the needs created by the pandemic; a good example of this is the ventilator production by Dyson [

43]. In partnership with governments, the pandemic offers various opportunities for companies across sectors—commercial, social, and governmental—to address the significant issues faced by society [

16] (p. 279).

4. The Bright Side of COVID-19: Opportunities Offered by the Pandemic

The pandemic has many dark sides, but we can also identify general opportunities that may be available for companies and their stakeholders affected by the crisis. Practicing CSR during the pandemic requires companies to take practical measures to address risks related to the crisis in a way that mitigates adverse impacts on their stakeholders. This opportunity enables companies to build long-term corporate value and resilience in response to vulnerabilities, and create the most favourable prospects for recovery.

4.1. CSR and Resilent Companies

Resilient companies are those with “a capacity to perceive, avoid, absorb, adapt to and recover from environmental conditions that could threaten their survival” [

44]. In order to make a convincing argument for ex ante mandatory CSR approaches, it is worth discussing the link between CSR, corporate performance, and the characteristics of resilient companies. For example, stock price changes in a specific time period are a valuable evaluation indicator for resilient companies; by examining the relationship between pre-2020 corporate characteristics and stock price reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic, Ding et al. concluded that the pandemic-induced drop in stock prices was milder among companies with more active CSR activities [

45]. These more CSR-engaged companies also experienced higher profitability, growth, and sales per employee [

45].

These findings echo arguments related to other catastrophic events such as the 2007–08 financial crisis, when, as Lins et al. argued, companies with high social capital, as measured by CSR intensity, showed stock returns that were four to seven percentage points higher than those with low social capital during the financial crisis [

46]. These findings remind us of the significance of CSR investment and the co-relationship between investment and the resilience of companies. They are also consistent with business cases for CSR [

47], and the view that investments in CSR build trust with stakeholders who are then more willing to make adjustments to support companies in response to conditions that could threaten their sustainable development. In the era of the pandemic, it is increasingly relevant and strategic to apply sustainability-driven multi-stakeholder approaches as a means to improve medium- and long-term resilience. Resilient companies should regard “

CSR as an integral part of their innovation and transformation efforts”, which will help companies through times of crisis such as COVID-19 [

48].

4.2. Protecting the Vulnerable and Addressing Inequality Mid- and Post-Pandemic

The COVID-19 virus does not discriminate. However, inequality does, and the effects and impact of the virus are not standardised across demographics [

49]. Vulnerable cohorts in the pandemic have been the elderly, poor, indigent, incarcerated, indigenous, or disabled, who have been affected disproportionately in terms of their health, financial, and social outcomes [

50].

In the business environment of the pandemic, many of these vulnerable parties may be identified among company stakeholders, for example, among vulnerable employees, customers, or suppliers [

48]. Companies are expected to commit to more responsible and inclusive practices to identify and address vulnerabilities during the pandemic as part of their efforts to build recovery. The pandemic is having disproportionate effects on disadvantaged populations such as employees with zero-hour contracts, along with suppliers and their employees at the end of global value chains producing food and clothing in developing countries. The pandemic has further entrenched poverty and xenophobia, and has generated additional human rights and social issues.

The consensus is that priority should be given to the most vulnerable parties post-COVID-19, in order to build more resilient societies and companies. Businesses should start by identifying innovative resolutions for the tensions and paradoxes caused by conflicting stakeholders’ interests, so that a sustainable and socially responsible business case or policy can be crafted [

48].

The nature of the economic shock associated with COVID-19 has also exposed some new, and interacted with many old and profound, inequalities [

51]. CSR activities that aim to reduce such inequalities might focus on helping children with online teaching by designing free online learning platforms, or introducing technologies to assist employees to mitigate risks such as using robots to offer cleaning or health care [

52]. On further scrutiny, these CSR initiatives might even reveal additional opportunities for companies in addressing societal economic inequalities.

Analysing vulnerabilities, inequalities, and companies’ responses offers legislators a unique opportunity to build knowledge around the private law response to the challenges of the pandemic. Each company and each stakeholder group will be vulnerable in their own way, which may create inequity at different levels and scales of exposure. The construction of a vulnerability matrix and the identification of vulnerable parties with different dependencies are key before setting aside benefits or designing coping mechanisms to provide more meaningful and substantial care for vulnerable stakeholders.

4.3. Promoting More Resilient Companies to Promote Long-termism, Strategic Agility, and Dynamic Capability

In tackling a global health crisis, resilience requires not only system-level readiness but also organisational support [

16] (p. 279). Making more inclusive business the “new normal” has never been more significant in response to the pandemic, in order to build more resilient and equitable societies for the benefit of vulnerable communities [

53]. In order to mitigate the magnified existing vulnerability and inequality brought by COVID-19, corporate leaders need to reimagine the nature and scope of CSR, and make active efforts to “

maintain economic viability while also laying the foundation for a just, equal, and integrated society” [

54].

As for the nature of CSR, the focus on CSR should go beyond philanthropic responsibility, so that companies can fulfil their CSR creatively based on their advantages and strengths. Rather than being limited to fulfilling a philanthropic responsibility by engaging in a set of charitable activities, the sphere of CSR should expand proactively, acknowledging the parallel impacts of corporate behaviours on enlarged social, environmental, and human rights aspects in pursuit of corporate aims, while simultaneously taking steps to minimise the negative impact of COVID-19.

In addition to the nature of CSR, the promotion of more resilient companies should also re-evaluate and re-strategise their CSR policies in line with long-termism, strategic agility, and dynamic capability. Dealing with urgent crises such as COVID-19 requires a fundamental shift from optimising principally for shorter-term performance to ensuring longer-term resilience [

55]. Companies should embed CSR as an essential part of their innovation and resilience-building efforts, and should make efforts to be prepared for future crises. In response to the uncertainty, urgency, and mutability of the risky business environment in the era of the pandemic, competence should be built to achieve strategic agility and dynamic capability.

The acknowledgement of and a renewed focus on CSR policies are in line with recommendations in favour of strategic agility as the “

ability to quickly and appropriately respond to or drive change while maintaining flexibility and focus” [

56], by creating new markets with new products that reach new customers so that companies can contribute to wider society in the areas where they are most capable. Agility may be accomplished from two levels; the first requires directors to respond swiftly to indirect stakeholders’ needs, informed and facilitated by stakeholder communication, while the second requires directors to have regard for the interests of indirect wider stakeholders based on corporate strategy. The implementation of strategic agility also reminds us of the benefits brought by mandatory CSR policy, which makes identifying the stakeholder matrix and building a vulnerability matrix a compulsory and hopefully a useful exercise for each company with a unique stakeholder network.

Preparation for CSR will also support companies to develop dynamic capabilities, in the shape of “

the ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments” [

57,

58] (p. 515). Companies need to develop their capacity to align corporate services and business priorities with stakeholders’ needs, including those of non-contractual stakeholders. Companies need dynamic capabilities to develop a sustained competitive advantage by creating intangible and valuable assets, as these abilities are key for exploiting more possibilities and forming effective business strategy [

59]. Therefore, in the COVID-19 business climate, dynamic capabilities involve a readiness to fulfil various responsibilities in order to achieve social and environmental goals. Such actions will facilitate more timely and effective contingency planning, and allow a more rapid recovery. This will enable companies to embed ethical issues into their strategies as they progressively transform their business models and ultimately recognise their role in society, consistent with the political CSR school of thought [

60] (p. 261). Guided by goals such as strategic agility, dynamic capability will allow companies to obtain comprehensive knowledge of the detailed risks they will face in the future.

5. Mandatory CSR: A Brief Evaluation

5.1. Why Mandatory CSR?

As a result of the current ongoing social, environmental, and financial turmoil, governments across the world have increasingly been intervening in decision-making processes at the level of corporations [

61]. The justification of mandatory CSR rests on the inadequacy of voluntary compliance and the urgency of addressing social and environmental challenges. The pandemic has further exposed the decreasing efficiency of traditional mechanisms of national or transnational governance in protecting vulnerable parties from corporate externalities [

62]. The political theories of CSR that claim a new political role for corporations because the “

social responsibilities of businessmen arise from the amount of social power that they have” are becoming increasingly relevant in the current economic climate [

63] (p. 45). As the result of the pandemic, global value chains are being strongly challenged for their inconsistencies and absurdities [

60] (p. 263). Mandatory CSR will facilitate the transformation of CSR norms from a narrow philanthropic responsibility-centred CSR to a more sustainability-motivated and strategy-driven one. If protecting stakeholder interests through business judgements becomes mandatory before stakeholders’ rights and interests are harmed, it will be more likely that companies will make well-informed decisions and develop their business activities in a prepared, manageable, and purposeful environment.

A legislative approach aimed at promoting CSR gives legitimacy to directors to consider and include the interests of non-shareholder constituencies when they discharge their CSR duties, which is a key element to promote sustainable development [

64]. The concept of sustainability is extensive and encompasses multiple dimensions, primarily in terms of economic, environmental, and social aspects that are complementary and interlinked [

65] (p. 46). It is defined as “

the result of the growing awareness of the global links between mounting environmental problems, socio-economic issues to do with poverty and inequality and concerns about a healthy future for humanity” [

66] (p. 39). The legislative approach to promote sustainable decisions also integrates social, environmental, and human rights concerns in the decision-making process, in such a way as to lead to an internalisation of externalities [

67].

5.2. Why Corporate Law?

With unprecedented social distancing rules and the disruption of international carriage of goods, the pandemic has added impetus towards arguments in favour of a more localised approach in response to social and humanitarian crises. This localised approach limits the inputs from international law or international recognised standards. In order to mitigate these vulnerabilities, apart from regulation by domestic laws with a direct impact on certain stakeholders’ rights, such as employment law, environment law, or consumer protection law, the duties to comply with laws such as industry standards and stakeholder pressures are inseparable from corporate law and corporate governance.

Many harms and damages done to vulnerable parties are irreversible. Therefore, it makes sense to make sure regulatory approaches are involved at the decision-making stage, to stop directors making irresponsible decisions that may lead to irreversible social or environmental damage. Furthermore, it is often difficult to establish a direct causal link between corporate misconduct and social, environmental, or human rights damages, and it is usually almost impossible to identify a single perpetrator. It is therefore necessary to rationalise the need to protect vulnerable parties with the highest dependency in a preventative rather than a compensatory manner.

As a result, directors will find “their decision tree considerably trimmed and their discretion decidedly diminished by mandatory legal rules enacted in the name of protecting stakeholders” [

68] (p. 111). Corporate law questions the dogma of the shareholder value principle and facilitates regulatory approaches such as directors’ duties at the decision-making stage, to stop directors making irresponsible decisions that may lead to irreversible social or environmental damages. In order to mitigate, ameliorate, and compensate for vulnerability, corporate law will require companies and their directors to provide assets in the form of benefits or coping mechanisms.

Specific implementation plans may demonstrate that it is unrealistic and impractical to embed the detailed regulation of decision-making power within companies, where over-regulating could damage the objectives of the best interests of the corporation. However, as evidenced by the Business Roundtable announcement by US companies that rejected the shareholder primacy norm and promoted the creation of value for all stakeholders in August 2019 [

69,

70,

71], COVID-19 has reignited the debate on corporate objectives and affirmed the necessity and accelerated the process of change proposed in these “

modernized principles” [

72], making it irrational for companies to return to old business operational approaches [

73,

74]. This makes the commitment by CEOs of the Business Roundtable to serve all stakeholders even more salient [

48]. Although this statement is not innovative, since it is actually a revision of the 1981 statement from the same group advocating explicitly that corporations are run principally to serve the interests of their shareholders [

75], in our opinion, the revised statement is an important signal that reinforces a stakeholder-oriented approach and its implications in company law. Considering the emergence of increasingly disturbing and potentially crippling issues such as rising income inequality, social welfare, and job security in the era of the pandemic, it is also a signal for companies to catch up with this attitude shift. The shift may also encourage more companies to operate within the progressive corporate law environment and offer a renewed focus on sustainable recovery, which should encompass the interests and needs of a broad array of stakeholders implemented within corporate law approaches, such as imposing wide legally recognised duties.

5.3. Achiving Sustainable Recovery through Corporate Law in the Time of the Pandemic

Sustainable recovery should be the goal for post-crisis legislation, considering that the nature of current legislations, such as the UK’s Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020, tends to relate to temporary and short-term impacts. The term ‘‘sustainability’’ emphasises an aptitude to prolong or maintain into the future; “

being a sustainable business means thriving in perpetuity” [

76] (p. 8). Integrating sustainability transparency strategically into corporate policy will involve a greater insight into the future. These companies are more likely to design policies in response to the damages caused by COVID-19, and will be much more agile in responding to unexpected events in the future. In order to achieve sustainable recovery and enhance CSR compliance [

77,

78], it is key to reconsider the scope of CSR beyond “doing good” in the category of philanthropic activities. We argue that company law will contribute to mandatory CSR policies, establishing a reference framework of corporate strategy and vigilance planning as measures to achieve sustainable recovery.

In response to the challenges of COVID-19 and goals to create, develop, and reconstruct resilient and agile companies, directors need to manage the conflicting interests of various stakeholders and treat building resilient companies as a core competency for post-pandemic transformation [

79]. This legal requirement will not only change corporate behaviour in the long term, but also enable directors to vigilantly manage risks in relation to the potential impact of COVID-19 on their stakeholders. In other words, in addition to promoting more accountable companies and imposing sanctions for their misconducts ex post, preventative approaches through corporate law with an internal influence on corporate behaviours and boards’ decisions will help board members to maintain a balance of attention between more active involvement in ethical initiatives and the independence of boards in making decisions. These approaches will encourage proactive legal risk management, and will therefore change the corporate culture by including building resilience or sustainable recovery as critical pillars for long-term prosperity and value creation.

In the era of the pandemic, companies need to set the foundations for enduring success by reimagining how they will recover, operate, and organise post-pandemic [

80]. Companies are now part of a dynamic world with a strong trend of continuous change, which requires flexibility and agility to allow the business society to remain closely connected to the latest environments, challenges, and needs. Companies need to confront new and stubborn economic and social uncertainties and risks, which generate or accelerate vulnerabilities within the business environment. The risks involved as the result of COVID-19 include reputational risks, health risks, and legal risks. In the era of the pandemic, the key point of this wide variability is that societies are exposed to risks for which no single mechanism is adequate to cope with them. These risks are beyond individual decisions, and addressing them will require partnerships among companies, stakeholders, governments, and international bodies. The pandemic embeds companies in “

a diffuse and multi-layered quagmire of management challenges” [

27] (p. 281), and although it is unrealistic to expect to be able to predict future crises, it is possible and desirable to be prepared to minimise their impacts on society by learning from the consequences of the current outbreak and potential contributions by companies. The characteristics of urgency, unpredictability, and accelerated multiple vulnerabilities and risks all give legislators legitimate reasons to instruct companies to prepare for similar crises in a robust, transparent, consistent, and deliberate manner, with supervisions and public enforcement power from governments and public authorities.

6. Ex Ante Corporate Law Measures for Sustainable Recovery and Development

The pandemic consolidates and re-emphasises the relevance and importance of CSR in the current context in supporting companies to shoulder their responsibilities towards society. Just like other corporate scandals and financial crises, which had enormous impacts worldwide and produced urgent calls for the revision of the shareholder primacy norm [

81,

82], COVID-19 will change the path of law reform in the future, particularly in terms of a heavier reliance on technology. It also offers another opportunity to revisit the effectiveness and emphasis of corporate law and its mission to address social challenges. These legal approaches are expected to help companies to achieve behavioural change through compliance, and support them to achieve a cultural transformation from traditional short-term philanthropy to a sustainability-driven CSR strategy to serve the public interest. As a result, companies with good compliance records will build long-termism into their strategic planning through inventiveness, liberality, and courageousness.

Due to the vast spectrum of unprecedented government interference and the urgency of addressing vulnerability among stakeholder communities, companies, policy makers, and board members need to reconsider the implementation measures in CSR law in order for them to be recalibrated with the emerging “new normal” of the business world. In addition to immediate measures to address urgent CSR challenges during the pandemic, such as creating safe working environments for employees, COVID-19 has created a significant opportunity to pursue and adhere to new values and agendas for companies. Preventative ex ante measures should ensure that companies are equipped with resources, support from governments and boards, and clear goals to empower them to fulfil their social responsibilities. This section will discuss the advantages of these approaches and their function to facilitate and implement company CSR goals.

6.1. Ex Ante Measures and their Advantages

For definitional purposes, focusing on CSR strategies and the perspective of stakeholder protection, on the one hand, ex ante approaches tend to mitigate the risks of various stakeholders by forestalling or controlling companies’ decisions, activities, or proposed transactions. On the other hand, ex post approaches are not premeditated to restrict corporate decisions or actions. These ex post approaches only come into play when a decision or action discriminatorily or unfairly harms stakeholders owing to circumstances or to the outcome. The distinction between the two approaches primarily rests on the different enforcement treatments, namely legal bans or limitations or selective assessment [

83].

A number of the traditional dichotomies of legal theory may be expressed in terms of temporal categories, in particular as tensions between before-the-fact considerations and those that arise after the fact, namely ex ante facto and ex post facto [

84]. As planning is extremely important to minimise the multiple risks arising as a result of COVID-19, policy makers should consider how to promote and acclimate ex ante planning approaches in company law legislations. Ex ante governance is implemented through “

expanding, constraining, or channelling power in the corporate ecosystem” [

85] (p. 621). In practice, taking Delaware as an example, “

courts are willing to uphold new breeds of ex-ante bylaws as long as the proposals are carefully crafted, and do not purport to encroach too far on substantive corporate decision-making” [

85] (p. 621).

Ex ante CSR measures are also linked with specific lawsuits that the boards wish to avoid, in terms of their companies, shareholders, stakeholders, NGOs, or government agencies. In the post-pandemic era, it is hardly surprising to expect budget cuts related to CSR spending, and the number of the companies liable for mandatory CSR contributions, such as those required in the Indian Companies Act 2013, is likely to shrink significantly due to pandemic-led disruptions to the companies’ financial incomes and profitability. Companies need to choose the causes for the CSR projects more judiciously, taking a differentiated approach to projects with different priorities and detailed planning to mitigate risks and address vulnerabilities.

6.2. Applying Ex Ante Measures to Achieve Strategic Agility

In the era of COVID-19, corporations need to reconstruct their corporate policies and make a swift transition to creating shared value for both themselves and society at large, in order to support their agile adaptation to the global value chain changes brought about by disruptions to transportation, logistics, and the mobility of people and resources [

86] (p. 601). Strategic agility will equip companies with capabilities to make swift decisions and adjustments to these decisions by simultaneously considering as many alternatives as possible [

87]. Strategic agility also necessitates the skills of processing smooth and rapid transformations in the companies’ configuration processes, implemented through business model innovation [

88], different corporate activities, and changes such as variation of the board structure or promoting more sustainable supply chains through corporate extraterritorial responsibilities [

89].

In order to navigate conflicting stakeholders’ interests and paradoxical pathways within corporate decisions, strategic agility will help companies to continuously adjust and adapt to a strategic management of corporate challenges in the era of the pandemic and its aftermath. This is particularly important considering that companies are confronting increasingly complicated and multi-dimensional pluralistic tensions during and after the pandemic, since COVID-19 is unlikely to be the last crisis that humanity will confront in a time also characterised by “

global warming, the biodiversity crisis, [and] environmental disturbances” [

90]. Strategic agility will help companies to “

stay ahead of the game” [

91] and enable them to prepare for urgent and uncertain challenges in the future.

In order to achieve strategic agility in line with companies’ dynamic capability, company strategies should also cover the interests of certain indirect stakeholders. This may be achieved by including stakeholders who do not have direct contractual relationships with companies, in order to maintain a good trade-off in the stakeholder paradox pathways and meet the needs of particularly vulnerable stakeholders as the result of the pandemic. The stakeholder map will need to be considered beyond immediate and obvious key stakeholders such as employees and customers. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the vulnerability of global supply chains to external shocks, which has accelerated and exposed vulnerability in supply chains such as the interests of vulnerable employees of overseas suppliers in the garment industry, or smallholder farmers in developing countries.

The pandemic requires companies to respond to uncertainty with strategic agility, which will enable them to achieve a competitive advantage by capitalising on innovative CSR. It is critical for companies to consider their business priorities and strategic direction when formulating and implementing their CSR policies, so that they can cultivate the capabilities required. On the one hand, companies must focus on surviving the impact of COVID-19 in the short term. On the other hand, many are already shifting their focus to the post-pandemic era, considering less disruptive ways of running their companies. Strategic agility will embrace open-minded leadership and accelerate the development of innovative and inclusive business models. Strategic agility will also enable companies to be able to react to fluctuating business environments and institutional conditions, and adapt their business models on a continuous basis [

88].

6.3. “Corporate Social Competence” As a Compliance Principle

“

The pandemic has clearly challenged a number of existing CSR assumptions, concepts, and practices” [

27] (p. 280), including corporate lawyers’ understanding of the application, emphasis, and enforcement of CSR. We argue that future CSR research should take seriously the need to develop more inclusive business models of risk management, in order to help companies to prepare for economic recovery and potential future crises. Vigilant companies will gain an edge after the pandemic. This may be achieved by clearly outlining sustainability plans and initiatives that demonstrate how they will meet the expectations of their stakeholders and build their competence. Maintaining a vigilant attitude with regard to managing the challenges brought by the pandemic will be significant in an increasingly competitive and uncertain marketplace and business environment.

The nature and intensity of concerns about the harms and hazards of corporate misconduct amid COVID-19 have also called for “CSR-ready” companies to mitigate vulnerabilities. With clear inequalities and an urgent need to support vulnerable stakeholders and wider communities, this crisis is an opportunity to strike a balance between corporate power and poor accountability mechanisms, along with fading trust in corporations and directors. The pandemic has opened the door to a revised understanding of accountability with a wider scope, as directors take ownership of the results of their actions in response to stricter scrutiny from the government and the public, which may ultimately lead to them being answerable for their actions. However, we claim that ex ante measures to facilitate and enhance the effectiveness of accountability should carry the same weight, if not more, as the ex post measures that are designed to correct misconducts. These ex ante measures should help companies to achieve readiness by providing a pathway and an agenda for their activities, so that corporate decisions can be consistent with the stated purposes and objectives embedded in companies’ constitutional documents. We term this characteristic of companies “corporate social competence”. It is seen as a compliance principle which will have significant impact in terms of the manner in which corporations are managed and risks are evaluated. “Corporate social competence” should be enriched and scrutinised through stakeholder participation and communication. Increasing the pressure to give serious expression to stakeholder demands seems to offer a precious opportunity to develop an innovative and meaningful legislative approach to CSR with well-designed components. The government should not only strongly encourage companies to reconsider their CSR plans so that they can transform their priorities “

from surviving to thriving” [

80], but also create a legislative environment in which responsible boards could direct or convert “

companies affected by the coronavirus back to sustainable success in a manner aligned with the interests of wider society” [

92]. Pre-set corporate purposes, key CSR priorities, and sustainable performance indicators will enable companies to map stakeholder coalitions, investigate the nature of each stakeholder interest and power, construct a matrix of stakeholder priorities, and monitor shifting coalitions [

93]. Companies need to address the urgent, rapidly evolving needs of stakeholders, and use strategic agility to weigh corporate priorities accordingly. The notion of “corporate social competence” and its implementation measures, which will be discussed in

Section 7, will help companies to recognise the nature and contributions of certain under-appreciated stakeholders, and include their interests in corporate purposes and CSR policy so their interests may be explicitly recognised. “Corporate social competence” may be also seen as a criterion that requires directors to reconsider CSR strategies and business models prudently and change the way they are perceived by communities and stakeholders, ultimately changing their CSR practice and performance.

“Corporate social competence” has implications at two levels. At the level of boards of directors, board members need to be adequately prepared for socially responsible leadership, and they should be sensitised enough and prepared to fulfil their duties by engaging in CSR activities as prescribed in their CSR policies. At the organisational level, corporations need to be prepared for a marked increase in unpredicted social, environmental, and human rights challenges and scrutiny from stakeholders, including shareholders, supervisors, and other external gate keepers, in terms of their CSR policies.

We think the notion may be most appropriately adopted in soft law legislation, such as corporate governance codes. The pandemic has highlighted the role played by companies not only as a source of societal and environmental risks but also actors that are highly exposed to such risks, and therefore who should play a proactive role in addressing them [

27]. While “

modern societies are exposed to risks for which there are no mechanisms to adequately cope with them” and which become “

an inherent part of modern society” in the era of the pandemic [

27] (p. 281), an understanding of CSR law needs to be supplemented by ex ante preventative and preparative measures. “Corporate social competence” will help companies to understand CSR as a generalised societal concept; one specific impact on corporate behaviour that “corporate social competence” might have is to encourage a more widespread use of CSR policies and planning, and correct the corporate behaviour and practices of erring corporations.

7. Legislative Approaches to Promote “Corporate Social Competence” in Corporate Law

“Corporate social competence” is proposed in this article to make the consideration of ethical notions in company law into precautionary, preventative, and due-diligence-oriented measures. The role of directors to comply with the “corporate social competence” principle would include formulating CSR policies in advance and setting a business model that will interpret the directors’ best interest duty to give priority to those corporate purposes that promote sustainability. In the long run, this compliance principle will empower companies to be more competent in balancing and prioritising competing stakeholders’ interests. The board will be collectively prepared by the creation of plans, and by pre-setting their corporate purposes to foster sustainable development. The principle could not only reaffirm corporate obligations to address sustainable development challenges, but also enable stakeholder groups that are included in CSR policies or the certification of more inclusive business models to participate in decision making, adopting a transparent and interactive approach grounded in stakeholders’ dialogue, participation, allegations, and scrutiny.

7.1. Mandatory CSR Policy and “Corporate Social Competence”

Although most CSR policies still rest at a voluntary level, mandatory CSR policy has already been introduced in some jurisdictions, notably in the Indian Companies Act 2013, in which a CSR committee must carry out tasks such as formulating and recommending a CSR policy, indicating the CSR activities to be undertaken by the company, and monitoring the enforcement of the CSR policy [

94]. Consistent with global trends [

95], Indian law places the board at the centre of the CSR policy-making process, and the effectiveness of CSR policies depend heavily on the instrumental power of boards [

96] (pp. 113–114).

If made mandatory, CSR policy is an ex ante legislative approach that prescribes and specifies CSR activities in the future. Ex ante rather than ex post regulatory instruments [

97] for corporate behaviours, such as the corporate duty to draft, publicise, and enforce CSR policy, focus on a proactive attention to policy and rules that will have an impact on directors’ compliance and their behaviours, so as to develop and plan for ethical, justice-oriented behaviours rather than engaging in an ex post analysis of outputs with the focus on corrective and distributive justice. Such a mandatory ex ante approach will direct future corporate behaviour and enable directors to reach broader goals beyond the triple bottom line [

98]. Directors can then adjust their decisions according to the necessities of the dynamic business environment in the era of the pandemic. Mid- and post-pandemic, instead of one-time resolutions, ex ante approaches are essential to establish strategic agility in response to ongoing challenges as “

a central tenet of a paradoxical approach” [

99] (p. 350).

Dealing with and balancing the conflicting interests of multiple stakeholders is a process of “working through” paradoxes, which reflects the reality in which corporations face multi-faceted pluralistic tensions rather than just one duality [

100]. Mandatory CSR policies may be able to deal with uncertainties and mitigate the risks brought by paradoxes by developing an organisational capability to manage paradoxes that will help companies to persist in times of uncertainty and adversity.

COVID-19 has magnified and accelerated the need for risk-led policy frameworks. Although somewhat controversial [

101], mandatory CSR policies will offer more consistent and enforceable opportunities for companies to deal with diverse and urgent risks in the era of the pandemic. The pandemic and its aftermath offer a window of opportunity for directors to reconsider their governance policy, including CSR policies and aligning priorities with the needs of stakeholders, with the particular attention to vulnerable groups as a result of the pandemic. CSR policies should be adjusted to respond to the challenges and social needs brought by COVID-19, and to prepare for similar future tests such as the compulsory closure of businesses.

7.1.1. Advantages of Mandatory CSR Policy Compared with Mandatory Philanthropic Responsibilities

CSR policy functions as a built-in guiding and governing mechanism whereby the board (or a committee of the board) establishes a shared framework to identify, quantify, manage, and monitor sustainability risks. The policy will ensure that companies’ activities reach beyond the compliance agenda made up of laws, ethical codes, and international norms. The scope of the decision making should go beyond the level of damage prevention or risk mitigation through board engagement. Stakeholders who understand companies’ needs and visions should be part of setting legitimate thresholds of due diligence [

102]. Stakeholder participation and communication are key for formulating clear and deliberate plans and policies to deal with CSR challenges in a consistent manner.

Compared with mandatory CSR spending, such as in the Indian and Mauritian CSR laws that have adopted a mandatory percentage of corporate profits as a CSR contribution with a focus on diverting annual profits to CSR activities [

103], mandatory CSR policies are more in line with the nature of business judgement rules [

104,

105,

106] and the subjective nature of directors’ fiduciary duties [

107]. CSR policies will likely create unequal value [

108] beyond the fixed amount of CSR contributions based on a certain percentage of companies’ profits. In the era of the pandemic, the value created by socially responsible corporate conduct based on companies’ comparative advantages may be much higher than the cost of the activities, especially in the case of activities promoting public health or mitigating extreme vulnerability. CSR policy measures, rather than mandatory quantitative donation policies, will enable companies to create significant value based on their comparative advantages. For example, companies may take the opportunity to adjust their production lines to manufacture products and equipment essential to the fight against COVID-19, such as ventilators [

43,

109], hand sanitiser [

110], or PPE [

111].

In promoting the sustainable development of companies, creative CSR initiatives today will create long-term value and define future legacies. Another good example, which started pre-COVID-19 but seems even more relevant in the context of the crisis, is Project Last Mile initiated by Coca-Cola. This project aims to make a change to the accessibility of life-saving medicines in Africa by sharing the expertise and logistic reach of the company with governments across Africa, so that the company can make a contribution to critical improvements in health systems [

112]. The expected value of this contribution will likely be highly significant in tackling humanitarian crises as well as the current global health crisis.

Companies should articulate cohesive and integrated CSR policies that reflect their core strengths and institutional capacities [

113]. Formulating a CSR policy containing detailed CSR programmes will not only reflect the commercial and societal values of companies, but also address social, human rights, and environmental issues in a more strategic and planned manner. A strong CSR policy will assist companies to maximise their societal value and help to establish a thoughtful, progressive, and active mindset that will be helpful in defining and operating a paradox perspective on CSR. This perspective facilitates “

interrelated yet conflicting economic, environmental, and social concerns with the objective of achieving superior business contributions to sustainable development” [

114] (p. 237).

CSR policies with a focus on strategic agility also help companies to respond to changes faster and more sensitively. This ex ante approach will also lead to positive ex post protection for directors, as mandatory CSR policies would give legitimacy to boards to implement corporate policies to address the urgent needs of the most vulnerable parties and deliver distributive justice in the era of the pandemic. A classic principle from distributive justice, e.g., Rawls’ difference principle, advocates rearrangements to our basic institutional structures to benefit the prospects of the least advantaged members of society [

115] (p. 266), and his definition of justice requires correcting any inequality that is “

arbitrary from a moral point of view” [

115] (p. 72).

7.1.2. CSR Policy Informed and Scrutinised by Stakeholders

If stakeholders participate in boards to help make decisions and contribute their wisdom, they can be regarded as stakeholder directors of the company together with other board members. If participation in corporate governance by stakeholders can be implemented through a formal mechanism to acknowledge the significance of the relationships between stakeholders and the company, it is more likely that the wellbeing of the stakeholder groups they represent will also be included in the board’s decision-making agenda [

116] (p. 876). Therefore, boards with stakeholder directors may expedite more explicit recognition and appreciation of stakeholder concerns, with powerful and legitimate representation as a part of a company’s dominant coalition [

117]. Ultimately, this will realise the institutionalisation of stakeholder inclusion in favour of a more diverse structure, which is key for addressing future crises.

From the perspective of government proposals, a green paper in the UK proposed “

improving the diversity of boardrooms”, so that board composition better reflects the demographics of stakeholders and “

a broader range of social perspectives, talent and experience can be brought to bear on decision-making” [

118] (p. 35). A stakeholder director system was proposed to “

bring a new perspective to board discussions” [

118] (p. 40). Creating “

stakeholder panels” was also suggested “

for directors to hear directly from their key stakeholders and amplify voices with different backgrounds and perspectives” through their participation in board meetings or by initiating discussions with board members [

118] (p. 38).

In addition to stakeholder directors as voices on the boards, an independent sub-committee may be established as another way to assess and address CSR challenges through participation in CSR policy formulation. The establishment of a sub-committee of representatives with different interests could address the choices of each stakeholder and make corporate decisions jointly [

119]. The establishment of sub-committees has been suggested to provide better board effectiveness, since they play an active role in delegating tasks and result in fewer decisions to be made [

120]. Apart from formulating CSR policy, the CSR committee [

121] could be assigned tasks such as monitoring spending patterns, drafting CSR reports, conducting investigations into cases where allegations are made in terms of social and environmental damages, and communicating with wider stakeholders concerning their enquiries and needs [

122] (p. 52).

In order to improve the strength of CSR committees, they may also benefit from the inclusion of stakeholder representatives by accommodating the notion of stakeholder participation. These would mean that CSR committees, stakeholder representatives, or stakeholder counsels will be more likely to be exposed to stakeholder scrutiny, and will be able to respond to expectations from stakeholders for more socially responsible corporate actions [

123]. Issues of independence, size, power, and diversity have been highlighted as important factors to enhance corporate social performance [

121] (p. 1930), suggesting, for example, a CSR committee with female leadership, which is an issue that has been discussed in the era of COVID-19 [

124,

125,

126,

127]. Stakeholder participation and stakeholder directors will help to formulate more stakeholder-friendly and appropriate CSR policy that addresses the most immediate and high-priority CSR challenges.

7.2. (Re-)Registration of More Inclusive and Sustainable Business Models

Contractual documents, such as a company’s constitutional documents, can be used as ex ante legislative measures to promote sustainable companies. Ex ante measures in relation to business models are primarily reflected in the articles of association. The articles of association will ensure that companies commit themselves to embracing social and environmental sustainability and social change. Just as covenants govern the purpose of the companies in terms of shareholders’ rights, certain formats of articles of association will be able to protect company purposes through capital raises, leadership changes, or mergers and acquisitions. Shareholders in these purposeful companies will hold companies accountable not only for their profit, but also for creating the greater good. Corporate law approaches play a crucial role in enforcing the rules of business and helping to institutionalise those rules to create and sustain purposeful companies supported by stainable business models.

However, these approaches cannot achieve their goals effectively in the absence of norms and values that are accepted by corporations globally. If corporate insiders adhered to norms only insofar as they were policed, doing business would barely be possible. No oral agreements could be made, detailed written contracts would be required at every single stage, and state agents would have to supervise the carrying out of those contracts closely. Transaction costs would overwhelm the gains from most exchanges. If business is to function, certain established business norms must be widely accepted by arguing that it is in a company’s long-term interest to adhere to them.

One of the primary concerns related to unsatisfactory CSR practice rests on the erroneous assumption that companies cannot successfully establish a business model that creates effective stakeholder trade-offs [

128,

129]. When addressing stakeholders’ needs and identifying the nature and scope of the tensions between them, it is advised that directors should start by revising the company’s business model as part of their strategy making or business planning [

48]. One key argument for dealing with crises such as the pandemic is to encourage companies to shift towards more inclusive business models [

53] because of the urgent need for involvement and contribution from the private sector, and a causal link with a fundamental shift towards more progressive corporate objectives, business cultures, and corporate values. An inclusive business model is a type of sustainable business that builds bridges between stakeholders, especially vulnerable ones, and the business community in order to create shared value [

130,

131]. Inclusive companies are more acquainted with the challenges faced by those at the base of the pyramid who are, more than ever, at risk [

132] (pp. 6–7).

7.2.1. Taking the Pandemic as an Opportunity

The COVID-19 crisis is generating enormous challenges for small and large corporations worldwide, and is having an impact on practically all the Sustainable Development Goals [

133]. It has presented corporations with a variety of unforeseen challenges. Many companies are expected to need to ask for help from public funds, and governments are injecting vast sums over a prolonged period of accommodative monetary policy to ensure sufficient market liquidity and low borrowing costs and support businesses through this challenging time. Swift and strong government actions include financial aid and bailouts, or nationalisation at an extraordinary level. Together with efforts from multi-lateral development banks and finance institutions, governments have made a substantial commitment to supporting a green recovery through public resources. The question for CSR policy makers is whether funding should be allocated based on criteria around sustainability for a green and inclusive economic recovery from the pandemic. A green recovery with consistent and enduring contributions from companies will significantly enhance the resilience of companies, economies, and societies in general.

Church leaders in Britain have suggested that companies registered in offshore tax havens should be refused corporate bailouts [

134]. The Financial Times suggested that directors “

should agree to sensible tests being attached to bailouts to avoid reputational damage to the entire business community” [

135]. Positive Money, a financial campaign group, and YouGov, a British international internet-based market research and data analytics firm, also reported that 63 per cent of the UK public believes that bailouts should come with social and environmental strings attached [

136]. McKinsey & Company have also emphasised the importance of corporate values and purposes, encouraging board members to test their decisions against corporate purposes during times of great uncertainty [

137].

Hence, it seems rational to claim that the pandemic may be an opportunity for governments to create conditions for bailout requests and financial assistance, and an accelerator for rebuilding and innovating current business models. This may be achieved by requiring companies to perform in a socially responsible manner, such as re-registering as “benefit companies” or B-Corps [

138], thereby helping to address global challenges such as the looming climate and humanitarian crises [

139]. To ensure that companies are required to fulfil their responsibilities, re-registered companies will be adherent to “

the highest standards of verified social and environmental performance, public transparency, and legal accountability to balance profit and purpose” [

140]. Echoing this proposal, in an open letter to the UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak, Greenpeace, a worldwide NGO with the vision of “

a greener, healthier and more peaceful planet”, advocates that any government support must come with strict conditions, including protecting workers, the climate, and the public [

141].

The COVID-19 crisis is intensifying and impacts us all, especially the most vulnerable, who are also the most at risk from corporate misconduct and irresponsible decisions. Corporations like B-Corps, which have made firm commitments to practise CSR actively and are prepared to make necessary adjustments during times of economic and social turbulence [

142], are needed more than ever to mitigate the challenges brought by the pandemic to economies, infrastructures, and health and financial systems, so that companies can make sustained contributions toward an inclusive and equitable economy. With a pledge to balance profit and purpose with strict legal accountability and an authentic commitment to purposeful and sustainable impacts on people, the planet, and profit, these corporations will help to mitigate the risks from the current financial and public health crises [

143].

The pandemic has also stimulated a worldwide desire to “do good”. The contribution from more inclusive business models can be a key formal mechanism for better livelihoods in response to this global desire, especially in places that traditional businesses and government programmes fail to reach, by engaging with the most vulnerable communities as one part of a sustained global effort. If the sustainable nature of these companies is recognised and protected by law, they can be (re-)registered as companies explicitly adopting a corporate objective to create a substantial positive impact on society and the environment [

144] (p. 6). These companies will not renounce pursuing profit, but will expressly and legitimately embrace the pursuit of other non-financial goals. It also affirms the expanded directors’ fiduciary duties requiring directors to consider non-financial interests, and the duty is always accompanied by a disclosure obligation to report on companies’ overall social, environmental, and human rights performance [

145] (p. 520).

7.2.2. Taking “Benefit Corporations” as an Example

A typical example of an inclusive business model is benefit corporations, which institutionalise a new hybrid corporate form of business that allows for both profit and social objectives. “

A benefit corporation is a traditional corporation with modified obligations committing it to higher standards of purpose, accountability and transparency” [

146]. It is “

a legal tool to create a solid foundation for long term mission alignment and value creation. It protects company missions through capital raises and leadership changes, creates more flexibility when evaluating potential sale and liquidity options, and prepares businesses to lead a mission-driven life post-IPO” [

146]. These companies regard purpose as the central characteristic, while also embracing the need for profit to deliver that purpose. They commit to produce a benefit or purpose on top of their for-profit objective, while voluntarily adhering to higher accountability and transparency standards.

New companies can incorporate as benefit corporations in any state where this business model is legally recognised and protected. Existing companies can also become benefit corporations by amending their governing documents. In most states, amendment requires a two-thirds supermajority vote of all shareholders. In benefit corporations in the US, the interests of a specific public benefit (stakeholder group) are identified when registering the company, and the constitutional documents make it explicit in law that their directors and officers will consider the specified stakeholders’ interests in addition to maximising shareholder wealth [

147] (p. 96). These companies were legally created in 2010 in Maryland in the United States [

148]. According to the legislation, benefit corporations “

shall have a purpose of creating general public benefit” [

149], where public benefit is defined as “

a material positive impact on society and the environment, taken as a whole” [

149,

150]. They may now facilitate and identify “

general public benefit” or “

optional specific public benefit” as corporate purposes [

149].