Abstract

Although each landscape has its own identity, only some of them are recognized as nationally important because of their cultural and natural values and their contribution to national identity. In Slovenia, these landscapes are listed in the national Spatial Development Strategy (adopted in 2004). However, this list was neither supported by implementation instruments nor integrated in any conservation or management policy documents and was poorly integrated into spatial plans. The aim of this research was to renew the methodology for identifying landscapes of national importance. The methods included in-depth interviews with experts, an online questionnaire, participatory workshops, and field visits. The questionnaire results showed that only eight landscapes from the original list of 62 were explicitly recognized as nationally important, which confirmed the hypothesis that the initial method was not transparent and that the criteria were biased. The proposed approach included the following criteria: (1) representativeness, (2) the quality of the landscape features, and (3) the cultural and scientific value. The methodology was accompanied with the list of landscape features and landscape types that are important for Slovenian national identity; recommendations for implementing the method on national, regional, and local levels; and the general guidelines for spatial planning and management of these landscapes.

1. Introduction

Every landscape has its own identity, which is based on (1) its physical characteristics, (2) the processes that take place in the landscape, and (3) the meanings that people attach to it [1]. Landscapes differ from each other and as such possess (more or less) unique geographical/spatial identities. The meanings people and societies attach to landscapes are prerequisites for establishing two other aspects of (landscape) identity—the identity of peoples and societies. Most individuals are attached to a certain place and/or a landscape and a share of their personal identities are derived from those places and landscapes. Similarly, cultural identity—a common/agreed identity of a social group—is built around the places and landscapes that a group inhabits and identifies with [1,2,3,4]. Collective memories often possess a strong spatial reference [5] since every event that is important for the social community takes place somewhere, and the location often gains the same importance as the event itself. Hrobat [6] defines this phenomenon as “the spatialization of time,” which is clearly expressed in the English language with the phrase “… the event took place …” Kučan [4,7], who researched the importance of landscapes for constructing national identity in Slovenia, argues that national identity is bound to the environment, to specific, and sometimes even idealized, types of landscape. These idealized types of landscape can be illustrated with a few important characteristics that are clearly expressed and that define their character, e.g., agricultural terraces, landmarks, etc. As such, they become a kind of “prototype” of a landscape. On the other hand, the concept of national identity is frequently built around places and landscapes that gained importance as symbols of a nation—either because of their unique and/or outstanding character and/or events that took place there. Many national landscapes are recognized as an inseperable part of national identity—e.g., in England [8,9], Scandinavian countries [10], the United States [11], and Slovenia [4,7].

The European Landscape Convention (ELC) [12] is the first document that stressed the importance of landscape as one of the cornerstones of European identity. As such, the concept of landscape identity should be considered in all three activities proposed by the ELC: landscape protection, management, and planning. One of the responsibilities of each country is to identify its landscapes, analyse their characteristics and changes, and assess them considering their values. Several European countries assessed their landscapes considering their character, whereas only a few examples of comprehensive (national) evaluations of landscape identity are reported in the literature.

Landscape character assessments are well renowned in England and Scotland [13,14,15], Ireland [16], Belgium [17], and elsewhere [18,19]. According to McCormack and O’Leary [20] (p. 143), landscape (character) should be assessed considering its three aspects: (1) the physical, (2) the visual, and (3) the image. These three aspects raise a question regarding the determination of boundaries. Defining boundaries is always a challenge in landscape research (and a must-do in landscape character assessment), since landscape is a continuum, where one landscape area “blurs” into another and where boundaries depend on the point of observation and the observer’s interpretation [21,22]. Whereas physical boundaries could be defined based on the boundaries between physical landscape layers (e.g., geology, soil type, land cover), which are more or less evident, visual boundaries are dependent on three-dimensional perception of the landscape and, therefore, visibility. The latter corresponds with the definition of landscape as “a portion of land which the eye can comprehend at a glance” [11] (p. 3). The importance of the visual component in landscape character assessment was also researched by Ode et al. [23] and Tveit et al. [24], who based their landscape character assessment methodology on nine concepts, which define the visual character of the landscape.

An evaluation of landscapes in terms of their identity was performed in Finland in 1993 and upgraded in 2010. The inventory followed the ELC and was based on the National Land Use Guidelines, which state that ”land use must secure that nationally significant built environments and natural heritage maintain their values.” Since it was carried out with a top-down approach by a group of governmental actors, it received several critiques regarding the exclusion of locals’ values and their vision for landscape change and development [25]. The method for landscape identity assessment in Latvia was not performed by government but by researchers and academics and was based on three stages: the assessment of the historic, visual, and cognitive elements in the formation of landscape identity. The combination of three aspects of landscape identity enabled identification of each landscape’s development, its visual character, as well as the subjective perception of selected individuals [26]. The latter was also researched by Ramos et al. [27], who, on a local level, have shown that multiple identities co-exist and that they affect future development.

Some efforts in landscape identity evaluation have been made in Slovenian (planning) strategy [28] but have never been properly integrated into policies and practice [29]. Furthermore, it was noticed that natural landscapes and contemporary landscapes that are well recognized among the general public in Slovenia are completely missing. The reason for that is the fact that the criteria for enlisting an area among nationally important landscape identity areas were based only on the cultural heritage value of the landscapes.

Although landscape identity is a topic of scientific discussion [1,3,5,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] as well as policy documents on international [12,39] and national levels [4,7,25,26], there seems to be little or no agreement about the definition of the concept.

Addressing landscape identity within different frameworks and on different scales and considering various historical, social and, environmental conditions results in various interpretations of the concept and in its vague definition.

Stobbelaar and Pedroli [34] (p. 334) have defined landscape identity as ”the unique psycho-sociological perception of a place defined in a spatial-cultural space.“ Their definition is accompanied by a discussion on landscape identity’s complexity and its several aspects. They argue that landscape identity is established along two axes: one between personal and cultural identity and the other between spatial and existential identity. The difference between geographical and existential identity can be grasped in the difference between the questions “where am I?” and “who am I?” [40]. The difference between a landscape’s and people’s (individual or collective) identity and their interdependence was recently discussed by Ramos et al. [35]. They understand landscape identity as the “… mutual relation between landscape and people“ and acknowledge that it can be interpreted either as the identity of the landscape itself or how people use the landscape to construct their own identity. Further, they argue that this dynamic relationship between people’s and a landscape’s identity is continuously established on two distinct levels. On the sphere of perception, landscape identity is based on its own character, as well as on the character of the landscape as a constructed entity. On the sphere of action, society interacts with the landscape on a physical level, driving change and altering its character. Different aspects of the landscape were also discussed by Jacobs et al. in their work “The Production of Mindscapes” [36]. They distinguished three dimensions of landscape: matterscape, powerscape, and mindscape, which could be interpreted as the physical, the social, and the personal/conscious reality of the landscape. Attempts to distinguish among different landscape realities, perceptions, and interpretations are helpful in explaining the complexity of landscapes and our relation towards them. Yet, at the same time, all these landscape realities are, as Schama [37] emphasized, indivisible: “before it could ever be a repose for the senses, landscape is the work of mind. Its scenery is built up as much from strata of memory, as from layers of rock” [37] (pp. 6–7). Therefore, different aspects of identities that arise from or are ascribed to landscapes often overlap and intertwine.

Another aspect that should be considered at this point is the identity’s sensitivity to change. Landscapes, societies, and individuals constantly change. Therefore, identities that are built around the relationship among these three also change. The relationship between landscape identity and change was recently explored by Butler and Sarlöv-Herlin [38]. They encountered questions such as, “who has a right to define the landscape identity? How can change develop new identities? What happens when the population changes?” [38] (p. 275). Such questions were also relevant for this study, in which we tried to define objective criteria for determining landscapes that are important for national identity in Slovenia. In addition, landscape identity is strongly associated with the concept of cultural landscape introduced by Carl Ritter as early as 1832 [41]. The basic idea is that there are two forms of landscape—the original one, existing before man-made change, and the one that is created and gained by humans who used significant effort, which is why it is called cultural landscape. The concept was further developed and promoted by Sauer, who defined it as “... fashioned from a natural landscape by a cultural group. Culture is the agent, the natural area is the medium, the cultural landscape is the result” [42] (p. 46). The concept of the cultural landscape is widely used in academia and has also been adopted by UNESCO, which has recognized 114 cultural landscapes as part of our collective identity since 1992 [43]. In Slovenia, cultural landscapes are included in the Register of Immovable Cultural Heritage as a type of tangible cultural heritage [44]. In February 2021, the register included 317 cultural landscapes. Some of them are locally or nationally significant since they have very clearly expressed characteristics (e.g., terraced landscapes [45,46]).

Furthermore, this human–nature interaction, reflected in different cultural landscapes [12]), also known as cultural and biological diversity [47], is a remarkable characteristic and is of utmost importance in Europe. Landscape diversity has also significantly influenced cultural and regional identities in Europe [12,48], and vice-versa, as pointed out by Ramos et al. [35] (p. 38): “The social and cultural traditions determine the different identities of landscapes: another culture, social structure or management traditions will shape different landscapes.”

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Background

For the purpose of our research, we focused on the criteria for evaluating the identity of landscapes. The current methodology in Slovenia dates back in the early 2000s, when the term “landscapes important for national identity” was introduced and these areas (from now on, “national landscape identity areas”) were designated within the Spatial Development Strategy of Slovenia [28]—a national strategic spatial planning document. The methodology for determining national landscape identity areas was based on cultural heritage landscapes already registered in the Register of Immovable Cultural Heritage [44]. The idea was that the concept would be further elaborated by determining areas and landscape features important for identity on lower—regional and local—levels, as well as guidelines for management of these areas. In 2005, a study entitled “Detailed Rules for Spatial Planning—Preserving the Identity of Slovenian Landscapes” [49], aiming towards determining landscape identity areas on lower levels and incorporating the guidelines for their management into spatial planning documents, was conducted. The results of the research project were never applied, and the concept never became operational in planning or management practice. Even the landscapes determined in the Spatial Development Strategy [28] were not legally designated nor gained any protection status. Therefore, specific consideration of their character in planning future development was left to the awareness of individual spatial planning teams. In addition, there was no consideration of the issue in the sectoral management programmes and plans.

The assumption that vague methodology and a lack of linkage to instruments were the reasons for poor implementation of the concept resulted in the decision of the responsible ministry to commission the update of the methodology and the redefinition of the national landscape identity areas. Since the Spatial Development Strategy [28] is also in the process of renewal, the ministries responsible for spatial planning and cultural heritage addressed the problem by issuing this research. The new methodology would be applied into spatial planning practice within one of the Strategy’s action plans. Therefore, the objectives of the research were:

- To redefine the concept of national landscape identity areas and renew the methodology for their designation;

- To elaborate guidelines for management of these landscapes; and

- To provide recommendations for applying the methodology on the regional and local levels.

The research was conducted in several steps, which included an extensive domestic and foreign literature review, a questionnaire, interviews, several methodology drafts, field surveys, and workshops.

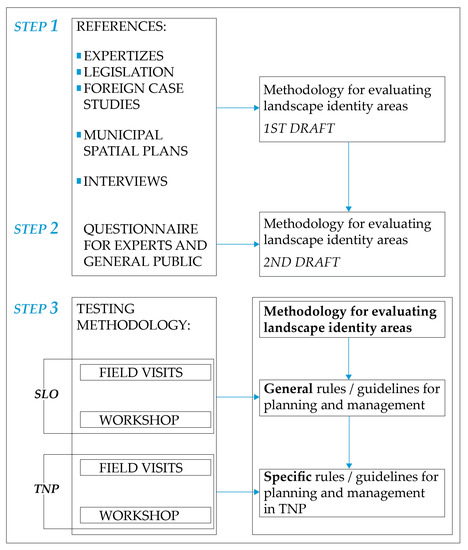

The research framework is presented on Figure 1 and described in the following paragraphs.

Figure 1.

The research framework.

2.2. Step 1—Drafting the Methodology for Assessing National Landscape Identity Areas

The project started with an overview of (1) national and international studies on landscape identity; (2) legislation, addressing landscape from various perspectives (e.g., nature conservation, cultural heritage); and (3) municipal spatial plans in selected areas. In addition, we performed 3 interviews with spatial planners and 6 interviews with representatives of relevant ministries (the Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning, the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Economic Development, and the Ministry of Culture) to find out to what extent the concept of national landscape identity areas is known and whether it is used in policy making.

Based on the findings, we drafted the methodology for evaluating landscape areas in terms of their importance for national identity.

2.3. Step 2—Performing an Online Questionnaire on the Relevance of Existing National Identity Areas and Redrafting the Methodology

Secondly, from 21 January to 27 February 2019, we assessed the relevance of the existing list of national landscape identity areas with an online questionnaire among experts from the fields of spatial planning, landscape architecture, geography, and similar disciplines. The respondents worked in research, education, public administration (state or municipal), spatial planning offices, design offices, and engineering. Three hundred sixty-nine online units were received, of which 203 were valid, but not all of them were fully complete (because mainly demographic data were incomplete, we did not specifically analyse them). In analysis, we took into account only the number of answers we received to each question. The questionnaire consisted of three major sections: (1) verification of the recognition of the areas listed in the Spatial Development Strategy of Slovenia [28], (2) verification of the recognition of contemporary landscapes, and (3) demographic data.

In the first section the respondents received the list of (existing) national landscape identity areas and were asked two questions for each one of them:

- Do you know this area? (yes/no)

- Do you consider this area important for national identity (yes/no) and (in case the answer is yes) which criteria have influenced your decision?

In the second section, nine photographs of contemporary landscapes were provided and respondents were asked to indicate in each case if it is important for the national identity of Slovenia and, in case the answer is yes, to also choose criteria that influenced their decision. In addition, the interviewees were also asked to add up to five landscape areas that they considered relevant for inclusion among nationally important landscape identity areas.

2.4. Step 3—Developing a Detailed Methodology for Identifying National Landscape Identity Areas, Performing Evaluation on Selected Case Study Areas, and Preparing Guidelines for Landscape Planning and Management

Considering the questionnaire results, we further elaborated the methodology for evaluating landscape identity areas.

The proposed methodology was discussed several times within the research team. Later, we performed field visits of sixteen selected case study areas in pairs. A special application form was prepared for identifying key landscape features and other details of each selected case. That enabled us to discuss the draft methodology already during the field visit and later within the whole group. After filed visits, the methodology was once again tested on two workshops, where the experts from the fields of spatial planning, cultural heritage protection, nature conservation, and other disciplines participated and contributed to the final result.

Finally, we prepared general guidelines for further management and planning of national landscape identity areas and specific guidelines for areas within Triglav National Park. Guidelines were accompanied with instruments for their implementation.

3. Results

3.1. Redefinition of the Concept of National Landscape Identity Areas

The methodology for evaluating landscape areas in terms of their importance for national identity was based on two concepts:

- Landscape features and landscape patterns that either represent a generic Slovenian landscape (e.g., a church on a hilltop) or a certain region (e. g. hayracks, different types of agricultural terraces) and that are considered relevant for landscape identity;

- Landscape identity areas that are unique and outstanding and therefore important for national identity.

A special consideration was given to including natural and contemporary landscapes and features among nationally important landscape identity areas, since the overview of existing nationally important landscape areas has shown that the existing selection of landscapes included only vernacular cultural landscapes.

3.1.1. Identity Value of Existing National Landscape Identity Areas

One hundred eighty-eight interviewees responded to our online questionnaire. Based on the answers, we set two thresholds for both questions: the first regarding their knowledge of the area and the second regarding the interviewees’ opinion on the relevance of the area for national landscape identity (Table 1).

Table 1.

The thresholds for direct listing and further evaluation of the areas and the total number of landscape areas that were classified into each group.

The results of the interviews, summarized in Table 1, showed that there was a strong agreement only about eight areas (out of 62) that were considered important for national landscape identity—Group 1. More than 75% of the interviewees knew these areas, and more than 90% of those who knew these areas considered them important for inclusion among national landscape identity areas. Thirty-one areas were classified into Group 2. These areas were either known to 50–75% of the interviewees, out of whom more than 50% considered them relevant for landscape identity, or were known to more than 75%, out of whom only 50–89% considered them relevant for landscape identity. Group 3 (twenty-three areas) consisted in areas that were either known among less than 50% of the interviewees or less than 50% of those who knew them and considered them important for landscape identity.

The interviewees also provided 356 suggestions, out of which three areas of Slovenia stand out in terms of their frequent appearance among the suggestions:

- The mountains and valleys of the Julian Alps with Triglav, the highest Slovenian mountain, as the most frequently mentioned (13 times) and Triglav National Park.

- Coastal areas with special emphasis on the Sečovlje salt pans (13-times) and coastal towns (especially Piran).

- The river Soča (Isonzo) and the landscape along the river with special mentioning of the towns of Bovec and Kobarid.

3.1.2. Evaluation Criteria and Pilot Areas for Evaluating Landscape Identity

The form for evaluating landscape identity areas included: (1) a general description of the area, (2) an overview of existing conservation regimes, (3) a list of identified landscape features and settlement patterns, (4) evaluation according to common criteria (list below), (5) definition of boundaries and naming, (6) a general evaluation of landscape quality, and (7) characteristic photographs of the area.

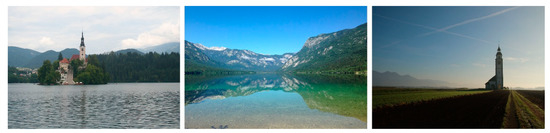

A list of landscape features proved to be an important part of the evaluation form, and it served as a checklist for the evaluating team. Landscape features were considered as crucial for the landscape identity of some landscapes, especially where they were perceived as a landmark because of their size and/or position (e.g., churches or single trees, see Figure 2), consistent performance (e.g., cultural terraces, see Figure 3), or regional or local characteristics (e.g., hayracks or shepherds’ huts, see Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Bled (left), Bohinj (middle), and Bitnje (right)—three landscapes with clearly expressed representativeness.

Figure 3.

Two types of cultural terraces: Gorjanci (left) and Jeruzalem (right).

Figure 4.

Landscapes with strong symbolic meaning, the Savica waterfall (left) and Triglav (middle), or continuity, the mountain pastures of Zajamniki (right).

After being discussed, tested, and updated several times, the following criteria for evaluating landscape identity were agreed upon:

- Representativeness—the area is important for national landscape identity because of its uniqueness (Bled, Bohinj) or for being a representative of a certain landscape type (Bitnje)—see Figure 2.

- Coherence and preservation/authenticity of landscape features and patterns:

- Coherence among natural and cultural features/characteristics—e.g., cultural terraces that only slightly adapt to topography (Dolenjska, Notranjska)—see Figure 3;

- Picturesqueness, visual attraction;

- Landscape heterogeneity.

- Cultural and scientific value:

- Historical and symbolic meaning—places and landscapes have a strong associative (e.g., the Savica waterfall), symbolic (e.g., Triglav) and/or historical value (e.g., the WW1 remains along the Soča/Isonzo river battlefield)—see Figure 3;

- Identity value—places and landscapes that the majority of citizens identify with (e.g., Planica, Bled);

- Continuity—places and landscapes with preserved settlement patterns, field division systems, etc. (e.g., Bitnje, Velika Planina, Zajamniki)—see Figure 4;

- Scientific and research value—landscapes that are important for studying natural phenomena (e.g., Karst) and/or historical landscape development.

Each area was assigned one of the three different values for each criterion, accompanied with a detailed explanation/argumentation:

- N—the area is considered of national importance for landscape identity;

- R—the area is of regional importance for landscape identity;

- L—the area is of local importance for landscape identity; and

- 0—the area has no importance for landscape identity.

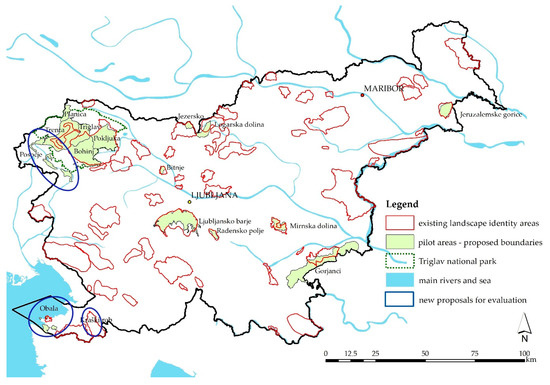

The methodology was tested by evaluating the importance of eleven pilot areas throughout Slovenia and an additional five pilot areas within Triglav National Park. All pilot areas are shown in Figure 5. We selected eight pilot areas considering the following criteria:

Figure 5.

Location of the pilot areas (among all existing landscape identity areas).

- Pilot areas should be distributed within all five landscape regions of Slovenia.

- Pilot areas that are already enlisted among national landscape identity areas were selected within all three groups from the questionnaire (areas of high, medium, and low importance):

- Ljubljansko barje;

- Jezersko;

- Zgornja Savinjska dolina (Logarska dolina);

- Jeruzalemske gorice;

- Radensko polje;

- Mirnska dolina;

- Bitnje; and

- Gorjanci.

Another three pilot areas were selected among the most frequently newly proposed areas in the questionnaire. These areas were wider and their boundaries not yet defined. Parts of them were also already enlisted among national landscape identity areas:

- i.

- Obala;

- j.

- Posočje; and

- k.

- Kraški rob.

Pilot areas within Triglav National Park were selected considering the diverse character of landscapes within Triglav National Park. These areas were:

- l.

- Triglav and the surrounding area (the highest mountain peak in Slovenia);

- m.

- Bohinj (glacier lake and mountain pastures);

- n.

- Pokljuka (high forest plateau);

- o.

- Planica (alpine valley with contemporary ski jumping facilities); and

- p.

- Trenta (alpine river valley with surrounding slopes and plateaus).

Trenta and Bohinj were already enlisted among existing national landscape identity areas and were considered of high importance for national identity among the respondents of the questionnaire.

An evaluation form was prepared in advance, as well as the relevant maps. Two experts visited and evaluated each pilot area to be able to discuss and argue the values ascribed to each criterion, as well as to avoid a subjective evaluation.

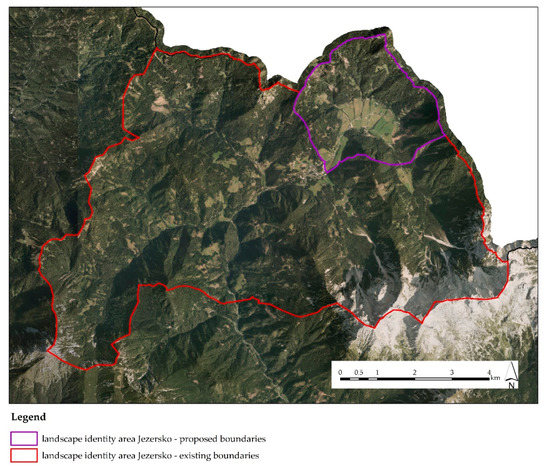

The evaluation of the pilot areas showed that to be able to evaluate the identity of selected landscape areas, the criteria should be broad enough to encompass the whole spectre of attributes that are relevant for landscape identity, but, at the same time, they should be clearly defined and non-redundant. Explanations with reference landscapes were added for every criterion to help the evaluating team. To avoid subjectivity in evaluations, we suggested that the evaluating team consist of at least two people, and that a comment with explanations and field observations should be added to each criterion. The evaluation of the landscape area Jezersko (Figure 6) is presented in the next section to illustrate the whole process.

Figure 6.

The proposed boundaries for landscape identity area Jezersko follow the ridges as the limit of visibility.

3.2. Guidelines for Managing National Landscape Identity Areas

The diversity of national landscape identity areas only allowed us to propose general guidelines for the management and planning of these areas. Our main recommendations based on field work focused on:

- Preserving existing land use, landscape features, and patterns that contribute to landscape identity.

- Preserving the traditional land division system, settlement patterns, and architectural typology.

- Promoting agricultural activities to prevent land abandonment and overgrowing, especially in marginal agricultural areas (e.g., mountain pastures). Besides, food production and agriculture in these areas has an important role in preserving landscape features and patterns with identity value; therefore, agricultural management technologies should adapt to that.

- Management and monitoring of landscape heterogeneity.

- Protection of natural landscape features (e.g., natural streams, hedges, individual trees, etc.).

- All development activities (e.g., housing, agriculture, etc.) should adapt to the environment’s carrying capacity. New developments should be planned considering the existing landscape character.

- Massive tourism should be prevented, and touristic development should be planned within the environment’s carrying capacity.

- Touristic infrastructure should be unified and minimized to avoid visual pollution.

Besides general guidelines, several instruments were suggested to implement these guidelines into planning and management practice. The instruments primarily focused on:

- The inclusion of landscape identity into expertises and planning acts.

- Educational activities for relevant stakeholders and the general public.

- The inclusion of recommendations into sectoral policies and management plans.

For every pilot area within Triglav National Park, specific guidelines and instruments for management were prepared as well.

3.3. Recommendations for the Method’s Application on Regional and Local Levels

Sixteen pilot areas were evaluated in terms of their identity value. Five areas that did not fulfil the criteria to be enlisted among national landscape identity areas proved to be important for regional identity. In spite of that, it should be noted that this should not be considered as a general rule. National, regional and local identities could not be evaluated considering the same methodology by simply determining different thresholds on the evaluation scale. Additional criteria could/should be introduced to evaluate the importance of landscape areas for regional and local identities. Our main recommendation for the method’s application on regional and local levels were:

- Further research should investigate the principles of regional/local identity and the differences between these two compared to national identity.

- The suggested criteria as well as the thresholds should be reconsidered and adapted to specific regional/local contexts.

- Additional criteria and characteristic landscape features could be added.

- Regional/local experts should perform the evaluation.

3.4. The Evaluation of Jezersko—An Example of a Case Study

3.4.1. Area Description and Conservation Regimes

Jezersko is a unique kidney-shaped plain of the Jezernica valley between the ridges of the Kamniško–Savinjske Alps and the Karavanke in the Alpine region. Because of the harsh climate and the remoteness of the landscape, the agricultural husbandry of the area was oriented toward sheep farming (Jezersko is renowned for its own breed of sheep) and some crops for self-sufficiency. A unique field division system, accompanied with typical pollarded ash hedges, gives the area a unique landscape character [50].

The area was designated as an outstanding landscape and has several conservation regimes: a cultural landscape, an historical landscape, a settlement cultural heritage, and natural value.

The reasons for selecting Jezersko among all pilot areas were:

- The area has a unique and well-preserved character, but, because of its remoteness and inacessibility, it was not considered as important for identity among interviewees.

- Despite the (so far) moderate touristic development, which did not negatively affect the landscape character and identity, uncontrolled future development could lead toward landscape degradation.

3.4.2. Characteristic Landscape Features

Besides the unique shape of the valley bottom, encircled with high mountains, Jezersko is renowned for its ash hedges on the parcel boundaries, as well as its individual trees and riparian vegetation. A small artificial lake, called Planšarsko jezero, is also one of the most recognizable features of Jezersko. A position at the foot of the mountains is a reason that several boulders can be found in the area. Some characteristic photos of Jezersko are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Representative photos of Jezersko with its main landscape features: valley bottom encircled with afforested slopes (top left), strings of ash trees (top right), Planšarsko jezero (bottom left), and pasture on the plateau (bottom right).

For the purpose of the research, a list of landscape features was prepared to be used as a checklist. The list is presented in Table 2, and landscape features that are characteristic for the Alpine region are written in bold. The evaluation of Jezersko is presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

A checklist of landscape features in Slovenian landscapes.

Table 3.

Evaluation of Jezersko according to selected criteria.

4. Discussion

4.1. Redefinition of the Concept of National Landscape Identity Areas

The need to redefine the methodology for evaluating nationally important landscape identity areas proved to be justified, since the results of our analysis showed that more than one third (23 out of 62) of the currently designated areas are not known or not considered important for national identity by experts. The most obvious deficiency of the current methodology is that it is based almost solely on cultural heritage criteria, leaving out the outstanding natural areas as noticed and expressed by interviewees, such as the highest peak, Triglav, or the outstanding Soča river. Additionally, none of the contemporary landscapes are listed, including those that have a special place in Slovenian national identity, such as the cradle of ski flights in Planica or the technical achievement of the Črni Kal viaduct.

The proposed starting point of the renewed methodology was consideration of landscape identity on two levels: a landscape can be an important element of national identity as a unique and outstanding place. The natural character of these areas is a foundation of their identity, which is additionally emphasized with man-made structures and/or symbolic meanings attached to that place/landscape (the highest Slovene mountain, Triglav, with the Aljaž tower, Bled with a church on the lake and a castle on the rock above the lake, etc.). These landscapes are known and can be identified by most Slovenian inhabitants as well as visitors.

Another level of identity is provided by landscape features and landscape patterns. Generic landscape features (e.g., a church on a hilltop), which appear throughout Slovenia, are a kind of “common denominator” of Slovene rural landscapes, and, therefore, they are a basis for establishing “the sense of belonging” as already highlighted by Kučan [4,7,51]. On the other hand, regionally characteristic landscape features and landscape patterns, especially when they are clearly defined, act as a means for distinguishing among regional landscape characteristics. As such, they are important for national, as well as regional, identity (e.g., a distinct form of cultural terraces that only appears in certain regions, a certain type of hayracks, a clearly expressed and preserved filed division system, etc.). However, this is not always recognized among heritage experts, as identified already by Kladnik et al. [45].

Criteria for evaluating landscapes in term of their importance for national or regional identity were developed through several tests and workshop discussions. The final set of criteria covered (1) the holistic and already established meanings of a landscape (site); (2) the analytic evaluation of individual features (a tangible presence) and their visual qualities, such as coherence, order, and diversity; and (3) the analytic evaluation of an intangible presence, such as an historical, symbolic, or scientific value. Similar criteria were introduced by Tveit et al. [24] and Ode et al. [23] in their study of visual landscape character.

Visual perception was considered extremely important when discussing landscape identity ([12] defines landscape as “an area perceived by people whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors”) since the perception of physical reality distinguishes the quantitative and objective physical reality from the qualitative and subjective “landscape,” which is the personal or, in our case, collective interpretation of this reality. Therefore, the boundaries of landscape identity areas were determined on the basis of visibility in the areas, where landscape identity was expressed as a typical/characteristic/well-known image (e.g., Jezersko, Logarska dolina), or on the basis of the perception of an area the locals identify with (e.g., Bohinj) but cannot perceive at a glance. The latter areas are usually larger, and they have a common cultural and/or physical denominator but also several characteristic “focal points” or “images” (e.g., Bohinj lake, mountain pastures, and the Savica waterfall). These areas correspond to McCormack’s and O’Leary’s interpretation of image units—units that relate to the apprehension of unity of the area because of cultural/historical/religious associations or, in our case, a dominance of a certain feature [20].

The question of delimitation links to another issue that has not been answered in full within this research; namely, where do the candidates for the nationally important landscape areas come from? The obvious ones are those from the original list, but this was considered incomplete. Some additional ideas came from the survey, but this was also not complete. The method and the criteria were adapted to the evaluation of already identified sites, although less so for the identification of all nationally important landscape areas. This gap remains to be explored in future studies.

4.2. Guidelines for Managing National Landscape Identity Areas

Landscape is a spatial as well as a temporal continuum, and change is one of its permanent characteristics.

Landscape identity, although often derived from its spatial characteristics, is not fixed and permanent. It changes and re-establishes itself as a result of action and interaction between the people and their environment. Landscape conservation principles should therefore be applied only for the most outstanding and unique landscapes, whereas guidelines for the development, management, and protection of all other landscapes—even those that are considered important for national identity—should be focused towards managing the “active and interactive” relationship between the people and the landscape. Prohibiting any change could therefore lead not towards preserving but destroying identity, since it destroys the relationship between the people and the place. These issues need to be particularly considered in the context of nationally or internationally recognized sites, because, as Lindström [52] warned, such recognition can imply the reinterpretation of global value and can make the understanding of local processes, even if they are authentic, difficult to include. Telling in advance which changes will be detrimental and which will not be detrimental or will even improve the landscape identity is an uncertain balance between giving very vague but probably right, and concrete but potentially wrong advice. Thus, guidelines should rather be seen as suggestions for how to navigate future planning scenarios and not as top-down, frozen rules.

4.3. Recommendations for the Method’s Application on Regional and Local Levels

The methodology was developed primarily for assessing nationally important landscape identity areas. The evaluation of the criteria was set on a four-stage scale: the area had N—national, R—regional, L—local, or 0—no importance for landscape identity. Although all the pilot areas that did not fulfil the criteria to be enlisted among nationally important landscape areas proved to be of regional importance, we believe that further testing of the methodology, as well as its refining, is needed for its application on regional and local levels. Several authors [27,38] emphasized that landscape identity can be established on various levels and that the construction of these identities does not necessarily follow the same rules or concepts. The generic prototype of the Slovene landscape is more a social construct than the real landscape, since it epitomizes the (otherwise geographically diverse) national space [51]. It is composed of individual landscape features that people identify with (e.g., mountains, (flat and fertile) fields, hayracks or trees, a church on a hilltop, etc.). On the lower (e.g., regional) level, this prototype can be much more accurate since the diversity of the landscape on the regional level is limited.

Regional and especially local identities were not investigated within this research. Therefore, we cannot argue that the same criteria with different thresholds could be applied for identifying regionally and locally important landscape areas. These two identities develop differently compared to national identity; they are less abstract and more tangible.

5. Conclusions

The current list of nationally important landscape identity areas in Slovenia is ill-fit and does not correspond to the actual understanding and perception of a nationally important landscape identity. Furthermore, the concept has been seldom used in spatial planning and in landscape management instruments. Thus, it is urgent to evaluate the current list according to the proposed methodology.

Only general guidelines for the management and planning of nationally important landscape areas were proposed. It turned out that the preservation of such areas is of utmost importance to (1) include them into expertise, planning acts, and management plans and (2) to raise the importance of their meaning among relevant stakeholders and the general public. Finally, the proposed methodology could only be partly used on regional and local levels. Additional criteria and characteristic landscape features should be added by regional/local experts, and thresholds should be adapted to specific regional/local contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.P.S., M.Š.H., J.H., T.P. and M.G.; Formal analysis, N.P.S., M.Š.H. and T.P.; Funding acquisition, M.G.; Investigation, N.P.S., M.Š.H., J.H., T.P. and M.G.; Methodology, N.P.S., M.Š.H., J.H., T.P. and M.G.; Project administration, M.G.; Software, N.P.S. and T.P.; Supervision, M.G.; Visualization, N.P.S. and T.P.; Writing—original draft, N.P.S.; Writing—review & editing, N.P.S., M.Š.H., J.H. and M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the project “CRP V5-1730 Upgrade of the methodology for designation of nationally important landscape identity areas” was financially supported by the Slovenian Research Agency, the Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning, and the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Slovenia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the character of the study. The study only dealt with pilot areas and national landscape identity areas will be further elaborated.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all interviewees, respondents to the questionnaire, and participants in the workshops who contributed their expertise and knowledge to the final result. M.Š.H. acknowledges financial support from the Slovenian Research Agency (research core funding No. P6-0101; Geography of Slovenia). N.P.S., T.P. and M.G. acknowledge financial support from the Slovenian Research Agency (research core funding No. P4-0009; Landscape as living environment).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Relph, E.C. Place and Placelessness; Pion: London, UK, 1976; ISBN 978-0-85086-055-9. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, K.H. Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language Among the Western Apache, 1st ed.; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-8263-1724-7. [Google Scholar]

- Južnič, S. Identiteta; Založba FDV: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kučan, A. The Modern Social Conception of Slovene Space = Slovenski Prostor v Sodobni Družbeni Predstavi. Geogr. Zb. 1997, 37, 111–169. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, M. Kolektivni Spomin; Studia Humanitatis: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hrobat, K. Ko Baba Dvigne Krilo; Filozofska fakulteta: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2010; Volume 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kučan, A. Prostorska Prepoznavnost Podeželja; Društvo krajinskih arhitektov Slovenije: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2013; pp. 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, D. British National Identity and the English Landscape. Rural History 1991, 2, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, W. The Making of the English Landscape; Hodder and Stoughton: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sörlin, S. The Articulation of Territory: Landscape and the Constitution of Regional and National Identity. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. Nor. J. Geogr. 1999, 53, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.B. Discovering the Vernacular Landscape; Yale University Press: New Haven, London, UK, 1984; Volume 1984. [Google Scholar]

- European Landscape Convention. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/176 (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Tudor, C. An Approach to Landscape Character Assessment; Natural England: York, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-78367-141-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sarlöv Herlin, I. Exploring the National Contexts and Cultural Ideas that Preceded the Landscape Character Assessment Method in England. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnock, S.; Griffiths, G. Landscape Characterisation: The Living Landscapes Approach in the UK. Landsc. Res. 2015, 40, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, H.; Boyle, K.; Rybaczuk, K. Landscape Character Assessment in the Republic of Ireland. LCN News Landsc. Character Netw. Newsl. 2006, 21, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eetvelde, V.; Antrop, M. Indicators for Assessing Changing Landscape Character of Cultural Landscapes in Flanders (Belgium). Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simensen, T.; Halvorsen, R.; Erikstad, L. Methods for Landscape Characterisation and Mapping: A Systematic Review. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wascher, D.M. European Landscape Character Areas. Typologies, Cartography and Indicators for the Assessment of Sustainable Landscapes; Landscape Europe: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, A.; O’Leary, T. Development and Application of Landscape Assessment Guidelines in Ireland: Case Studies using Forestry and Wind Farm Developments. In Countryside Planning; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 158–172. ISBN 978-1-84977-091-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. The Temporality of the Landscape. World Archaeol. 1993, 25, 152–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marušič, I. Regionalna Razdelitev Krajinskih Tipov v Sloveniji—Metodološke Osnove; Ministrstvo za Okolje in Prostor: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1998; Volume 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ode, Å.; Tveit, M.S.; Fry, G. Capturing Landscape Visual Character Using Indicators: Touching Base with Landscape Aesthetic Theory. Landsc. Res. 2008, 33, 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveit, M.; Ode, Å.; Fry, G. Key Concepts in a Framework for Analysing Visual Landscape Character. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkola, H. Administration, Landscape and Authorized Heritage Discourse—Contextualising the Nationally Valuable Landscape Areas of Finland. Landsc. Res. 2015, 40, 939–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ņitavska, N. The Method of Landscape Identity Assessment. Res. Rural Dev. 2011, 8, 175–181. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, I.L.; Bianchi, P.; Bernardo, F.; Van Eetvelde, V. What Matters to People? Exploring Contents of Landscape Identity at the Local Scale. Landsc. Res. 2019, 44, 320–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odlok o Strategiji Prostorskega Razvoja Slovenije (OdSPRS). Available online: http://pisrs.si (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Golobič, M.; Penko Seidl, N.; Pipan, T.; Hudoklin, J.; Šmid Hribar, M.; Kumer, P. Nadgradnja Metodologije Določanja Območij Nacionalne Prepoznavnosti Krajine; Univerza v Ljubljani, ZRC SAZU, Acer Novo mesto: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2020; p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, D. European Landscape Transformations: The Rural Residue. In Understanding Ordinary Landscapes; Yale University Press: London, UK, 2009; pp. 180–188. ISBN 978-0-300-18561-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tilley, C. A Phenomenology of Landscape; Berg Publishers: Oxford, UK, 1994; Volume 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Space and Place; University of Minesotta Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boillat, S.; Serrano, E.; Rist, S.; Berkes, F. The Importance of Place Names in the Search for Ecosystem-Like Concepts in Indigenous Societies: An Example from the Bolivian Andes. Environ. Manag. 2013, 51, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobbelaar, D.J.; Pedroli, B. Perspectives on Landscape Identity: A Conceptual Challenge. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, I.L.; Bernardo, F.; Ribeiro, S.C.; Van Eetvelde, V. Landscape Identity: Implications for Policy Making. Land Use Policy 2016, 53, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, M.; Lengkeek, J.; Dooremalen, H. The Production of Mindscapes: A Comprehensive Theory of Landscape Experience. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schama, S. Landscape and Memory; Vintage: New York, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-679-73512-0. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, A.; Sarlöv-Herlin, I. Changing Landscape Identity—Practice, Plurality, and Power. Landsc. Res. 2019, 44, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. 1972. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/convention-en.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Reading the Identity of Place. In Multiple Landscape: Merging Past and Present; 2004. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Derk-Stobbelaar/publication/40111226_Reading_the_Identity_of_Place/links/0c96051dc5796a55db000000/Reading-the-Identity-of-Place.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Potthoff, K. The Use of ‘Cultural Landscape’ in 19th Century German Geographical Literature. Nor. J. Geogr. 2013, 67, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, C.O. The Morphology of Landscape, by Carl O. Sauer; University Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Centre, U.W.H. Cultural Landscapes. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/culturallandscape/ (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Register Kulturne Dediščine RKD. Available online: https://gisportal.gov.si/portal/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=df5b0c8a300145fda417eda6b0c2b52b (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Kladnik, D.; Šmid Hribar, M.; Geršič, M. Terraced Landscapes as Protected Cultural Heritage Sites. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2017, 57, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipan, P.; Kokalj, Ž. Transformation of the Jeruzalem Hills Cultural Landscape with Modern Vineyard Terraces. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2017, 57, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M.; Emanueli, F. (Eds.) Biocultural Diversity in Europe; Environmental History; Springer International Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-26313-7. [Google Scholar]

- Antrop, M.; Brandt, J.; Loupa-Ramos, I.; Padoa-Schioppa, E.; Porter, J.; Van Eetvelde, V.; Pinto-Correia, T. How Landscape Ecology Can Promote the Development of Sustainable Landscapes in Europe: The Role of the European Association for Landscape Ecology (IALE-Europe) in the Twenty-First Century. Landsc. Ecol. 2013, 28, 1641–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hudoklin, J.; Selak, I.; Simič, S. Podrobnejša Pravila Za Urejanje Prostora—Ohranjanje Prepoznavnosti Slovenskih Krajin; ACER Novo mesto d.o.o.: Novo mesto, Slovenia, 2005; p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- Šmid Hribar, M.; Lisec, A. Protecting Trees through an Inventory and Typology: Heritage Trees in the Karavanke Mountains, Slovenia. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2011, 51, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučan, A. Constructing Landscape Conceptions. J. Landsc. Archit. 2007, 2, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, K. Universal Heritage Value, Community Identities and World Heritage: Forms, Functions, Processes and Context at a Changing Mt Fuji. Landsc. Res. 2019, 44, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).